Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

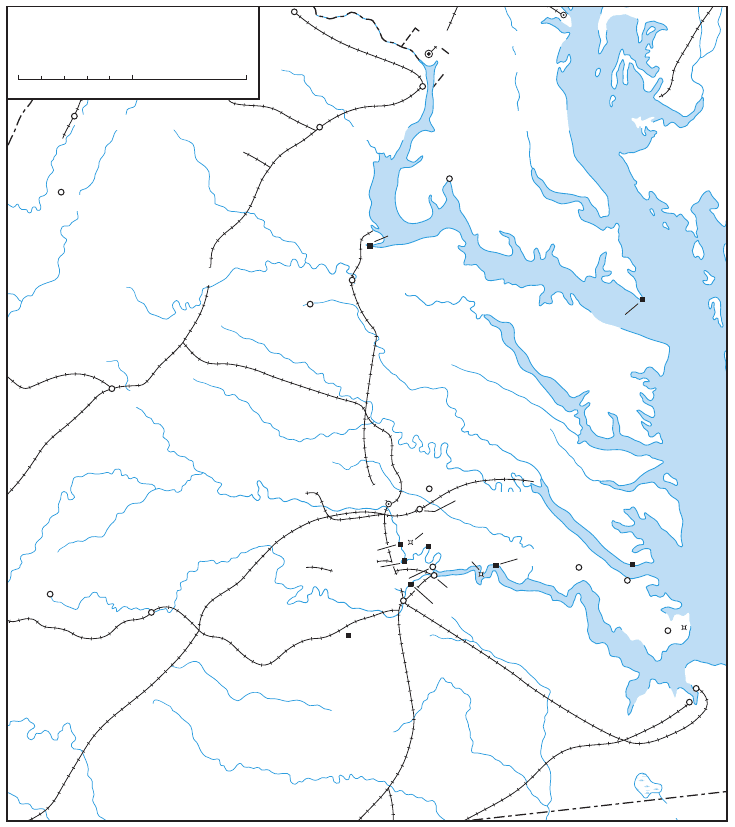

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

331

& keeping up with them in their raids which I begin to think are of very little ac-

count . . . as far as ending the war is concerned.”

69

Throughout the rest of March, Verplanck must have found Union operations in

Tidewater Virginia equally unsatisfactory. The day after Duncan’s brigade returned

to Yorktown, the 4th, 5th, and 6th USCIs boarded transports and crossed the James

estuary to Portsmouth. From there, passenger cars took the 5th eight miles south

toward the Great Dismal Swamp to guard the railroad against an expected raid

by Confederate cavalry. “The products of this region are pine, peanuts & sweet

potatoes,” wrote Lieutenant Scroggs, who had farmed in Ohio before the war and

found little to admire in the South. “No doubt a favorite resort of musquitoes in

their season. Truly a delectable country.” The threat of a raid seemed to evaporate

once the troops arrived. On 9 March, railroad cars and transport ships bore them

back to Yorktown.

70

There, they did not disembark. Instead, the 22d USCI joined them on the trans-

ports and all went up the York River to land at a tobacco warehouse on the oppo-

site shore, just above where the Mattaponi River joins the Pamunkey to form the

York. The point of the expedition was to punish Confederate sympathizers in the

region, who, General Kilpatrick claimed, had ambushed part of his cavalry during

the failed raid on Richmond ten days earlier. General Butler called it a matter of

“clearing out land pirates and other guerrillas.” Kilpatrick was to lead about eleven

hundred mounted men and six guns from Gloucester Point along the north shore

of the York River, driving before them two regiments of Confederate cavalry that

were supposed to be in the neighborhood, along with any irregulars. The infantry

from Yorktown, landing upriver, was to block the Confederate retreat.

71

The transports steamed up the York, sometimes running aground, and did not

reach the landing until well after dark. When they nally arrived, the infantry saw

“the whole horizon . . . ablaze with the camp res of men, who at that time ought to

have been twenty-ve miles below,” Assistant Surgeon Merrill wrote. Kilpatrick’s

men had moved forward before the troops from Yorktown had even arrived. Poor

communications between Kilpatrick and Wistar plagued the expedition during the

next three days, until rain and rising streams brought operations to a halt. The cav-

alry managed to burn public buildings and warehouses at King and Queen Court

House and took some fty prisoners, most of them civilians.

72

More serious than the failure of the expedition was the relaxation of discipline

that some ofcers saw in their men as they moved around the country in small

groups. “Kilpatrick’s men are in no sort of discipline & leave desolation wher-

ever they go, robbing defenseless men & women & in general are as lawless a

set of devils as they could well be,” Lieutenant Verplanck complained. In the 22d

USCI, Merrill wrote, Colonel Kiddoo “told the boys not to steal hens, chickens,

turkies, geese or anything of the sort, but if any of the above-mentioned called

them ‘damned niggers’ to knock ’em right over the head. Pretty soon up runs a

69

OR, ser. 1, 33: 170–71, 183–88, 202, 205, 207, 210, 213; Verplanck to Dear Mother, 13 Mar

1864.

70

NA M594, roll 206, 4th and 6th USCIs; Scroggs Diary, 6 (quotation), 7, and 9 Mar 1864.

71

OR, ser. 1, 33: 240–41, 662, 671 (quotation).

72

Ibid., pp. 243–44; C. G. G. Merrill to Dear Father, 13 Mar 1864, Merrill Papers.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

332

drummer boy with a dead goose: the Colonel asks him if he called him a ‘damned

nigger’; the boy says no, but that he hissed at him & so he hit him with his sword.”

Stories like this were common all over the occupied South; if the incident actually

occurred, the men of the 22d USCI were learning fast. “Disloyal” livestock was

fair game wherever Union armies went.

73

Ofcers of Duncan’s brigade seemed to think that their men’s foraging went

beyond acceptable bounds. Merrill saw an incident that revealed why the men may

have yielded to their emotions: “I found some of our boys hacking away at a sort of

cross T set up in the ground, with two pegs projecting from the upper crossbeams,”

he told his father:

It was a whipping post & they were in a perfect fury as they cut it down. It

seemed as though they were cutting at an animate enemy & revenging upon

him the accumulated wrongs of two centuries. As fast as one tired, another took

the axe & soon the infernal machine . . . came to the ground—never again to be

used for such a purpose—it was burned on the spot where it fell—I send you a

piece of it.

Despite the men’s legitimate grievances, ofcers began to grow tired of the season

of small expeditions and looked forward to a major campaign. Lieutenant Ver-

planck thought that raiding was “work unworthy of the true soldier.” During a

march through Mathews County later in the month, one ofcer of the 4th USCI

found it necessary to order one of his men to shoot another to interrupt his looting.

Lt. Col. George Rogers of that regiment reported that “one of the effects of such an

expedition [is] to destroy in a week that discipline which it is the work of months to

establish.” Curiously, no commanding ofcer in the brigade seems to have issued

a regimental order on the subject, which was also of continual concern to ofcers

of veteran white troops.

74

Elsewhere around the Chesapeake, great changes were under way. Ulysses S.

Grant, promoted to lieutenant general in early March, had come east to take charge

of all federal armies. “Now if he will . . . not become contaminated by his nearness

to Washington all will yet go well with us & we can look to the overthrow of the

rebellion before winter,” Lieutenant Verplanck wrote. General Burnside had also

come east, relieved from command of the Army of the Ohio but still leading the IX

Corps. He reported directly to Grant, since he was senior to Maj. Gen. George G.

Meade, who commanded the Army of the Potomac. (Burnside, one of that army’s

unfortunate former commanders, had marched it to disaster at Fredericksburg in

December 1862.) An all-black division was building in the IX Corps, as six recent-

ly organized regiments—the 19th, 30th, and 39th USCIs, all from Maryland; the

73

Verplanck to Dear Mother, 13 Mar 1864; Merrill to Dear Father, 13 Mar 1864; Bell I. Wiley,

The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1952), p.

236.

74

OR, ser. 1, 33: 256 (“one of”); Merrill to Dear Father, 13 Mar 1864; R. N. Verplanck to Dear

Mother, 2 Apr 1864, Verplanck Letters. On white troops, see orders to keep the men “well in hand”

during Sherman’s march through Georgia in OR, ser. 1, 44: 452–63, 480–85, 489–90, 498, 504–05,

513 (quotation). Books of the regiments in Duncan’s brigade contain no orders about discipline

dating from the spring of 1864. 4th, 5th, and 6th USCIs, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

333

27th, from Ohio; the 43d, from Pennsylvania; and the 30th Connecticut—reported

to corps headquarters at Annapolis, then moved through Washington to camp near

Manassas, Virginia. Regiments from Illinois, Indiana, and New York were en route

to join them.

75

Late in April, after months of debate, the U.S. Senate approved an Army ap-

propriation for the coming scal year. The act included a section that awarded

black soldiers military pay, rather than an unskilled laborer’s wage. It did not move

forward to House approval and presidential signature until 15 June, but soldiers

felt relieved in late April that it had gotten through the Senate. In the 5th USCI,

Lieutenant Scroggs had thought about resigning if an “inexcusably dilatory” Con-

gress did not provide for equal pay. He noted the news with satisfaction. Lieutenant

Verplanck was also elated. “The Government has at last determined to give us our

rights,” he wrote home, “and I am as happy as a clam at high water.”

76

On 22 April, Brig. Gen. Edward A. Hinks arrived at Fort Monroe to take com-

mand of the newly formed 3d Division, XVIII Corps, which was to include the

black regiments in Butler’s command. Duncan’s brigade at Yorktown struck its

tents and moved down the peninsula in what Lieutenant Scroggs called, after the

constant activity of previous months, “an easy march of twenty miles.” Besides

the 4th, 5th, and 6th USCIs, Hinks’ division included the 1st, 10th, and 22d in a

brigade commanded by General Wild, as well as Battery B, 2d U.S. Colored Artil-

lery. All busied themselves in preparation for the spring campaign. For Assistant

Surgeon Merrill, this meant combing out the unt men. “There are plenty of them

in this regiment,” he told his father, “men who ought not to have been enlisted and

who will have to be discharged, after . . . helping ll the [draft] quotas of towns

& cities in Penn[sylvani]a.” Merrill was not the only surgeon to complain about

recruits who joined their regiments without having undergone a physical examina-

tion at their place of enlistment.

77

Word of the Union defeat at Fort Pillow and the massacre of black soldiers

there reached Fort Monroe four days before General Hinks took command of his

new division on 22 April. Newspapers were still detailing those events the next

week, when reports arrived that black soldiers and white Unionists had been “taken

out and shot” after the surrender of the federal garrison at Plymouth, North Caro-

lina. Soldiers at Fort Monroe making nal campaign preparations bore this news in

mind when writing to their next of kin. One of Hinks’ staff ofcers told his wife:

Everything is in readiness. . . . The next ten days are to witness a fearful strug-

gle. If we succeed, it will be the beginning of better things. We must succeed,

failure for us is death or worse. This Division will never surrender, for ofcers

and men expect no mercy from the foe. . . . [A]lthough we know that some of us

75

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1046; Verplanck to Dear Mother, 2 Apr 1864.

76

OR, ser. 3, 4: 448; Scroggs Diary, 30 Mar (quotation) and 25 Apr 1864; R. N. Verplanck to

Dear Mother, 22 Apr 1864, Verplanck Papers; Edwin S. Redkey, ed., A Grand Army of Black Men:

Letters from African-American Soldiers in the Union Army, 1861–1865 (New York: Cambridge

University Press, 1992), pp. 229–48.

77

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1055; Scroggs Diary, 20 Apr 1864 (“an easy”); C. G. G. Merrill to Dear Father,

2 May 1864 (“There are”), Merrill Papers. For another complaint about unexamined recruits, see J.

Fee to Capt C. C. Pom[e]roy, 24 Mar 1864, 29th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

334

will in all probability never come back again, . . . I have yet to see the rst long

face or hear the rst regret.

Soon after Hinks arrived, Lieutenant Verplanck left the 6th USCI to join his staff.

One evening, Verplanck remarked to the other ofcers that “he felt just as he used

to [as] a boy when his folks were going to take him to the theater.” To his mother,

he wrote: “We are organizing our division as fast as possible . . . and then the rst

large body of black troops will go in together and will make an impression I be-

lieve such as has never been felt before.”

78

78

S. A. Carter to My own darling wife, 1 May 1864 (“Everything is,” “he felt”), S. A. Carter

Papers, MHI; R. N. Verplanck to Dear Mother, 26 Apr 1864 (“We are”), Verplanck Letters; New

York Tribune, 26 April 1864 (“taken out”). The most exhaustive study of events at Plymouth is

Weymouth T. Jordan Jr. and Gerald W. Thomas, “Massacre at Plymouth: April 20, 1864,” North

Carolina Historical Review 73 (1995): 125–93.

From before sunup until after sundown, soldiers at Fort Monroe during the

early days of May 1864 busied themselves preparing for the spring campaign. In

the 4th United States Colored Infantry (USCI), Sgt. Maj. Christian A. Fleetwood

interrupted his paperwork to spend a morning at target practice. “Fair shooting,”

he thought, “not extra.” Ofcers marveled at orders that restricted their baggage to

fteen pounds: “as well none as so little,” wrote 2d Lt. Joseph J. Scroggs of the 5th

USCI. “The bustle of preparation goes on vigorously and soon both men and of-

cers will be divested of everything except their accoutrements and the clothes on

their backs.” Also in the 5th, Lt. Col. Giles W. Shurtleff noted that orders assigned

each regiment only one wagon to haul its gear; ofcers had to store their roomy

wall tents and sleep in pairs in shelter tents like the men. “This seems hard,” he told

his ancée, “but I am rejoiced to see the commanding general go about his work as

if he meant to effect his object. . . . It will cause us great inconvenience and some

hardship and exposure; but what matter if we can more speedily accomplish the

work to be done?”

1

The new commanding general of all Union armies, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant,

had arrived in Washington that March from west of the Appalachians, where feder-

al troops had spent the previous two years advancing continually into Confederate

territory. While they satised day-to-day needs by stripping hostile country of food

for soldiers and animals, they moved ever farther from the depots that supplied

their clothing and munitions, neither of which could be replenished on the spot,

hence their habit of traveling light. Grant brought that method of warfare east, for

he intended to put all the Union’s forces in motion. Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks,

in Louisiana, would move up the Red River toward Texas. At the same time, Maj.

Gen. William T. Sherman would strike south from Chattanooga: “Joe Johnston’s

[Confederate] army his objective point and the heart of Georgia his ultimate aim,”

as Grant explained it to Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, who commanded the Army of

the Potomac. “Lee’s army will be your objective point,” Grant continued. “Wher-

ever Lee goes, there you will go also.” Grant issued orders that limited the number

1

C. A. Fleetwood Diary, 2 and 3 (quotation) May 1864, C. A. Fleetwood Papers, Library of

Congress (LC); J. J. Scroggs Diary, 1 (“as well”) and 2 (“The bustle”) May 1864, U.S. Army Military

History Institute (MHI), Carlisle, Pa.; G. W. Shurtleff to Dearest Mary, 2 May 1864, G. W. Shurtleff

Papers, Oberlin College (OC), Oberlin, Ohio.

Virginia, May–October 1864

Chapter 11

J

a

m

e

s

R

J

a

m

e

s

R

P

o

t

o

m

a

c

R

C

H

E

S

A

P

E

A

K

E

B

A

Y

Y

o

r

k

R

C

h

i

c

k

a

h

o

m

i

n

y

R

M

a

t

t

a

p

o

n

i

R

P

a

m

u

n

k

e

y

R

R

a

p

i

d

a

n

R

R

a

p

p

a

h

a

n

n

o

c

k

R

S

t

a

u

n

t

o

n

R

Dismal Swamp

A

p

p

o

m

a

t

t

o

x

R

S

o

u

t

h

A

n

n

a

R

N

o

r

t

h

A

n

n

a

R

Point Lookout

B elle Plain

G loucester Point

D eep Bottom

Wilson’s Wharf

Spring Hill

Drewry’s Blu

Dutch Gap

Fiv e Forks

Fort Monroe

Fort Gilmer

Fort Powhatan

Appomattox Court House

Farmville

Portsmouth

Hampton

Yorktown

Williamsburg

City Point

Bermuda Hundred

Fair Oaks Station

Cold Harbor

Spotsylvania Court House

Port Tobacco

New Market

Woodstock

Manassas Junction

Leesburg

Petersburg

Charlottesville

Fredericksburg

Alexandria

Norfolk

RICHMOND

ANNAPOLIS

WASHINGTON

VIRGINIA

MARYLAND

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

NORTH CAROLINA

VIRGINIA

1864–1865

0

5025

Miles

Map 8

Virginia, May–October 1864

337

of baggage wagons allowed to each regiment and to each brigade, division, and

corps headquarters. Meade’s army needed its wheeled transport to haul rations

and ammunition through the familiar, fought-over Virginia countryside between

Washington and Richmond (see Map 8).

2

While the Union’s main armies were in motion, a fourth, led by Maj. Gen.

Benjamin F. Butler, would advance from Fort Monroe up the James River toward

Richmond. Grant himself visited Fort Monroe in early April to discuss the move,

for Butler was a national gure, one of the nation’s leading War Democrats—cer-

tainly the most prominent one in uniform—and too important to ignore in forming

plans for the spring campaign. The two generals were in substantial agreement

about an attack up the James, but Grant thought it best to conrm the results of their

conference with a letter marked Condential. Concentration of force was essential,

he told Butler. As the Army of the Potomac advanced south toward the Army of

Northern Virginia and Butler’s Army of the James moved northwest toward the

Confederate capital, the two would draw closer together and eventually coordi-

nate their operations. Butler’s army would receive a reinforcement of ten thousand

men drawn from Union forces in South Carolina, Grant said. “All I want is all the

troops in the eld that can be got in for the Spring Campaign,” he explained in a

letter to Sherman. Since Butler had served only in administrative posts, Grant as-

signed Maj. Gen. William F. Smith, a former corps commander in the Army of the

Potomac, to direct command of operations. Grant, who had graduated from West

Point two years ahead of Smith, thought him “a very able ofcer, [but] obstinate.”

3

Butler’s force included a division of six USCI regiments—the 1st, 4th, 5th, 6th,

10th, and 22d, along with Battery B, 2d United States Colored Artillery (USCA).

Other black troops on the peninsula between the James and York Rivers included

the 1st and 2d United States Colored Cavalries (USCCs), at Williamsburg. Some

seventy miles to the north, but still within Butler’s command, the 36th USCI guard-

ed prisoners of war at Point Lookout, Maryland.

4

Brig. Gen. Edward W. Hinks commanded the six regiments that accompanied

the main force. A Massachusetts ofcer who had served with Butler in Maryland

during the rst weeks of the war, Hinks had received a severe wound while lead-

ing his regiment at Antietam in 1862 and had spent more than a year afterward in

administrative posts. When he saw that Butler was to take charge of the Depart-

ment of Virginia and North Carolina in the fall of 1863, he wrote to the general,

requesting a eld command. Hinks arrived at Fort Monroe in late April, just as

news of the Fort Pillow massacre reached the East. Within a week, he asked to

replace his division’s “unreliable” weapons, which might, he said, “answer for

troops who will be well cared for if they fall into [enemy] hands, but to troops who

cannot afford to be beaten, and will not be taken, the best arms should be given that

the country can afford.” The 1st USCI regiment, its colonel complained, carried

2

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Ofcial Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies, 70 vols. in 128 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1880–1901), ser. 1, 33:

827–29, 919–21 (quotation, p. 828) (hereafter cited as OR).

3

OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 3, p. 305 (“All I want”); 33: 794–95 (Condential); vol. 36, pt. 3, p. 43

(“a very able”). William G. Robertson, Back Door to Richmond: The Bermuda Hundred Campaign,

April–June 1864 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1987), pp. 18–24.

4

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1055, 1057.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

338

“second-hand Harper’s Ferry smooth bore Muskets (cal .69),” a model that pre-

dated the Mexican War. He asked for “the new improved Springeld muskets” to

replace them. The regiment’s correspondence gives no clear idea of when it re-

ceived new weapons, but a few letters and orders that summer indicate that authori-

ties took between six and eight months to act on the colonel’s request. Whatever

weapons Hinks’ regiments carried, by early summer each was able to furnish men

to form a company of divisional sharpshooters.

5

The other large concentration of black soldiers in the Chesapeake region was

the 4th Division of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s IX Corps. At the end of April

1864, it included the 19th, 23d, 27th, 30th, and 39th USCIs; ve companies of

the 43d; and four companies of the 30th Connecticut (Colored). Other regiments

were on the way to join it, from as far away as Illinois and Indiana. Its commander

was Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero, who had served with Burnside since the North

Carolina Campaign. In September 1862, he had led a brigade in the charge across

Burnside’s Bridge at Antietam. Ferrero had commanded a white division in the

IX Corps for eight months before becoming the 4th Division’s rst commanding

general on 19 April 1864.

All of the regiments in the 4th Division were of recent date. The senior

one, the 19th USCI, had completed its organization in mid-January 1864; the

39th, only on the last day of March. The 43d USCI and the 30th Connecticut

were still recruiting, sending companies to the front as men arrived to ll the

ranks. After mustering in at army camps in Connecticut, Maryland, Ohio, and

Pennsylvania, the regiments moved one by one to Annapolis, where Burnside

had his headquarters. On 25 April, they marched through Washington to take

station across the Potomac, near Manassas.

6

Whether from a belief that military movements should be kept secret—as

if nineteen thousand men passing a reviewing stand could be concealed—or

out of racial spite, Washington newspapers nearly ignored the IX Corps. The

Evening Star identied the troops as Burnside’s only after other papers men-

tioned their identity. The National Republican conned itself to a sentence:

“A large number of troops, infantry, artillery and cavalry, white and black, all

in excellent condition, was reviewed in this city by the President to-day.” The

Constitutional Union devoted more space to mocking Republican patronage

appointees than it did to describing the march itself: “As the column of colored

soldiers passed down Fourteenth street, last evening, the ofce holders, from

the Treasury and other places, whose number are legion, and who lined the

5

Ibid., pp. 947, 1020–21 (“unreliable”); Col J. H. Holman to Maj C. W. Foster, 23 Dec 1863

(“second-hand”), 1st United States Colored Infantry (USCI), Regimental Books, Record Group

(RG) 94, Rcds of the Adjutant General’s Ofce, National Archives (NA). NA Microlm Pub M594,

Compiled Rcds Showing Svc of Mil Units in Volunteer Union Organizations, roll 205, 1st USCI; roll

206, 5th and 6th USCIs; roll 207, 22d USCI. Private and Ofcial Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin

F. Butler During the Period of the Civil War, 5 vols. ([Norwood, Mass.: Plimpton Press], 1917), 3:

136 (hereafter cited as Butler Correspondence). Examples of 1st USCI ordnance correspondence are

Regimental Order 106, 28 Jun 1864, and Maj H. S. Perkins to Maj R. S. Davis, 23 Aug 1864, both in

1st USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

6

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1042. NA M594, roll 207, 19th USCI; roll 208, 30th USCI; roll 209, 43d USCI.

Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959

[1909]), pp. 116, 248–50.

Virginia, May–October 1864

339

streets, set up a shout of exultation, at the picture before them. They had no

shout for the white soldiers—no, none. Their hurras are for miscegenation and

the new order of affairs.” The writer may have thought the Treasury Depart-

ment worth mentioning by name because its secretary, Salmon P. Chase, was

the most outspoken abolitionist in the cabinet; but opponents of the adminis-

tration were not the only spectators that day who were skeptical of the black

troops. Elizabeth Blair Lee, sister of the postmaster general and wife of a naval

ofcer, wrote: “I watched Genl Burnsides Corps for an hour today—counted

ve full negro Regts . . . & two full Regts of real soldiers. . . . [T]he Negroes

were clad in new clothing marched well—every Regt had a good band of mu-

sic—& they looked as well as Negroes can look—but Oh how different our

Saxons looked in old war worn clothing—with their torn ags—but such noble

looking men.” Capt. Albert Rogall of the 27th USCI, which had left Ohio just

seven days earlier, remembered the day differently. “Secesh white spitting at

us,” he wrote in his diary.

7

The 19th USCI arrived in Virginia to nd its campsite a charred ruin. The

regiment’s predecessors “were awful mad to think they were to be relieved

by Colored Soldiers & they go to the front,” Capt. James H. Rickard wrote;

“they burned all their huts which they had all xed up so we have got to make

new ones. . . . Such is the feeling against Col. Troops.” Rickard may well have

7

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1045; (Washington) Evening Star, 26 April 1864; (Washington) National

Republican, 25 April 1864 (“A large number”); (Washington) Constitutional Union, 27 April 1864

(“As the column”); Virginia J. Laas, ed., Wartime Washington: The Civil War Letters of Elizabeth

Blair Lee (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), p. 372 (“I watched”); A. Rogall Diary, 26 Apr

1864 (“Secesh white”), A. Rogall Papers, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus.

Much of the District of Columbia was still rural during the Civil War. This photograph

shows cattle grazing on the south bank of the Washington City Canal. The south portico

of the White House is in the center of the picture, with the Treasury building to the east.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

340

been wrong; not every slight that the Colored Troops suffered was the result of

racial prejudice. Union troops across the South burned their verminous winter

quarters when the time came to leave them, although some pessimists in the

often-defeated Army of the Potomac cautioned against the practice. “Leave

things as they are,” one veteran recalled hearing them say that spring. “We may

want them before snow ies.”

8

The men of the 4th Division barely had time to improve their campsites,

for the Army of the Potomac moved south on 4 May. The position of the IX

Corps was awkward, for Burnside was senior to the army commander, Meade,

yet led a smaller force. Grant solved the problem by assigning Burnside’s corps

to guard the roads in the wake of Meade’s advance, from Manassas “as far

south as we want to hold it.” Within the corps, the 4th Division would guard

wagon trains. The forty-three hundred wagons and eight hundred thirty-ve

ambulances that belonged to the Army of the Potomac required more than

twenty-seven thousand horses and mules to draw them. If they had formed in

single le, Grant estimated, the line that resulted would have been more than

8

J. H. Rickard [no salutation], 29 Apr 1864, J. H. Rickard Papers, American Antiquarian

Society (AAS), Worcester, Mass.; Frank Wilkeson, Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army

of the Potomac (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1886), p. 41 (“Leave things”); Charles W. Wills,

Army Life of an Illinois Soldier . . . Letters and Diaries of the Late Charles W. Wills (Washington,

D.C.: Globe Printing, 1906), p. 231; W. Springer Menge and J. August Shimrak, eds., The Civil War

Notebook of Daniel Chisholm: A Chronicle of Daily Life in the Union Army, 1864–1865 (New

York: Orion Books, 1989), p. 12.

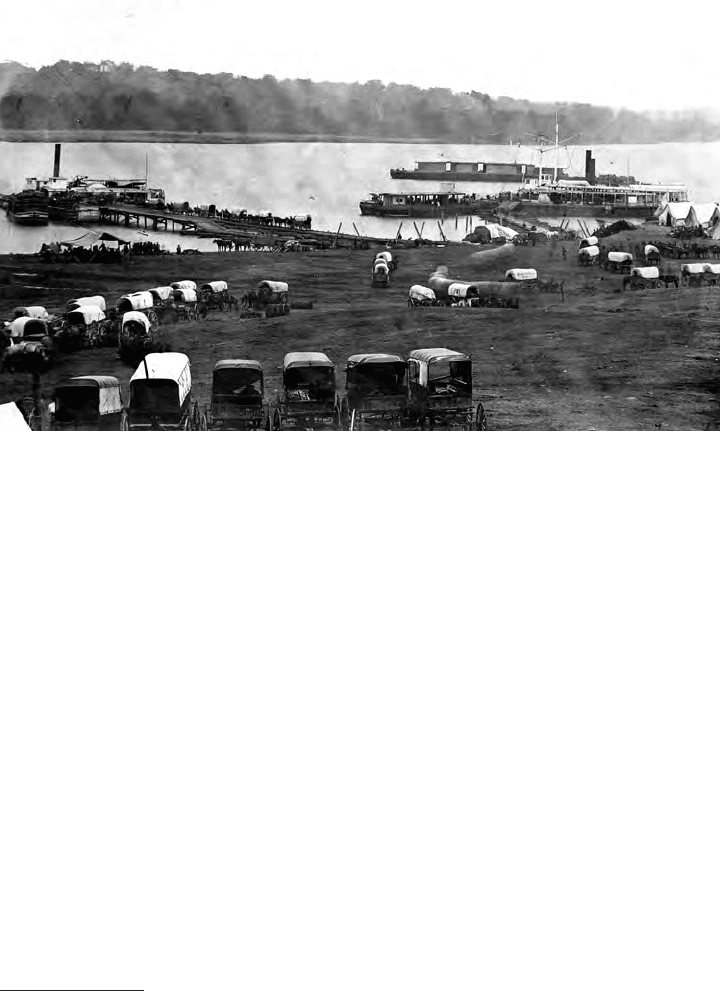

Belle Plain, one of the river landings that served the Army of the Potomac’s movement

toward Richmond in May 1864. Wagons carried wounded from the ghting to waiting

vessels and bore supplies back to the advancing troops.