Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

311

black membership, the club’s three hundred-dollar entry fee and sixty-dollar annual

dues had that effect.

28

Leaders of the city’s black community, some of whom had begun urging

enlistment in 1861, joined in enthusiastically. Fifty-four of them lent their names

to a recruiting poster that urged “Men of Color, To Arms! To Arms!” They or-

ganized a mass meeting on 24 June, and another one twelve days later at which

Frederick Douglass appeared among the speakers who urged enlistment. The

chief federal ofcial present was Maj. George L. Stearns, who had been recently

appointed recruiting commissioner for U.S. Colored Troops after several months

spent working closely with Governor Andrew to raise the two black infantry

regiments from Massachusetts. Companies of recruits formed in Philadelphia

as the men arrived there; when each company reached the required strength, it

reported to Camp William Penn, eight miles outside the city. There, a Regular

Army ofcer who represented the Provost Marshal General’s Ofce mustered

it into federal service and the company became part of a regiment. Between

recruits’ arrival and muster-in, the committee of civilian philanthropists took

28

OR, ser. 3: 376, 404–05; Census Bureau, Population of the United States in 1860, p. 410;

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (New York: Schocken Books, 1967

[1899]), pp. 17–24, 27–30; Roger Lane, Roots of Violence in Black Philadelphia, 1860–1900

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986), pp. 16–20; Chronicle of the Union League of

Philadelphia, 1862–1902 (Philadelphia: Union League, 1902), p. 445.

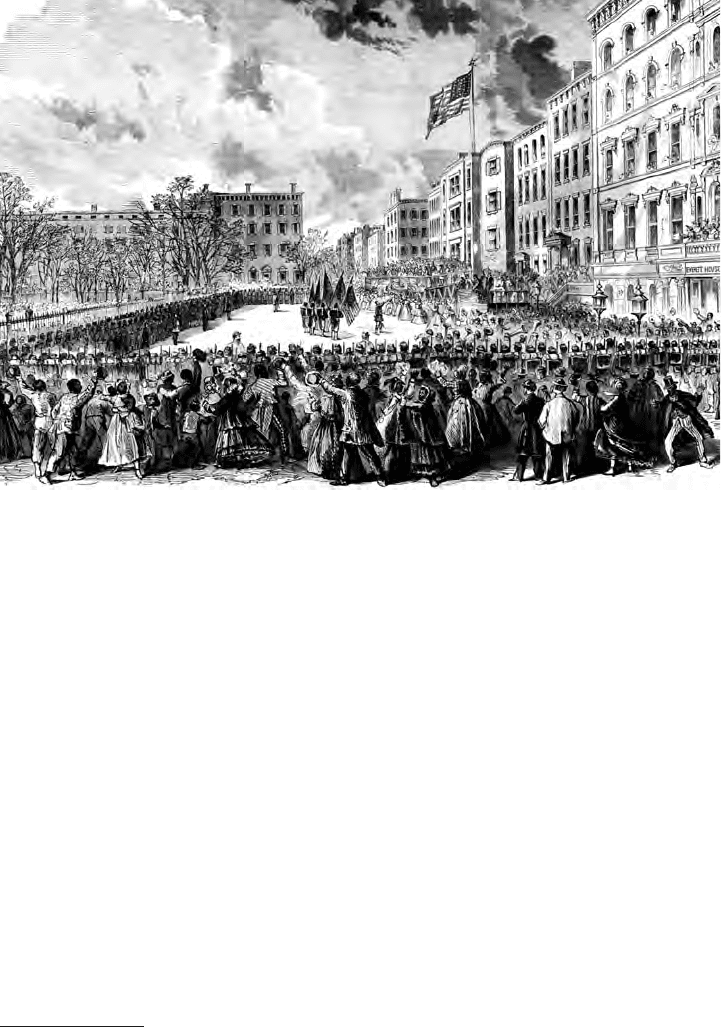

The 20th U.S. Colored Infantry receives its regimental colors, 5 March 1864.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

312

responsibility for feeding and sheltering them, a function that committees of

neighbors had performed when towns and counties across the North raised regi-

ments of white volunteers in 1861 and 1862.

29

By August 1863, the rst of Philadelphia’s black regiments, the 3d USCI, was

ready to embark for South Carolina. Two more, the 6th and 8th, were complete by fall.

Through the winter, Camp William Penn turned out black infantry regiments at the

rate of one a month. Eleven in all left Philadelphia by the end of summer 1864, most

of them destined for Virginia and operations against Richmond and Petersburg. Nearly

one in ten of all the Union’s black infantry regiments entered service at Camp William

Penn or in the city itself.

30

In other Northern states, governors kept greater control of recruiting and re-

tained the power to nominate ofcers. Nearly all of the ofcers of the 5th and 27th

USCIs (Ohio), the 28th (Indiana), the 29th (Illinois), and the 102d (Michigan) had

served in one of their state’s volunteer regiments or was at least a resident of that

state. Besides soldiers from his own state, the governor of Ohio named several ci-

vilians from Oberlin College, an abolitionist stronghold that had begun admitting

black students more than twenty years earlier. Although only white men ofcered

the Ohio regiments, the governor took advice on nominees from John M. Langs-

ton, a black Oberlin alumnus of 1849, and Langston’s brother-in-law, Ordinatus S.

B. Wall. Both men had recruited black Ohioans for the 54th and 55th Massachu-

setts and took an active part in raising the 5th and 27th USCIs.

31

Although the city of Washington, D.C., lacked powerful elected ofcials to pro-

mote black enlistment, it was nevertheless a good recruiting ground for a place its size.

Smaller than Albany, New York, in 1860, Washington had a black population that more

than tripled during the next ten years, from 10,983 (9,209 free, 1,774 slave) to 35,454.

Former slaves who ed to Washington from nearby rural counties in Maryland and Vir-

ginia increased the number of dwellers in the city’s crowded, unhealthy alleys tenfold.

Reecting the residents’ rural backgrounds, the source of income in more than half of

these alley households was unskilled labor. Wartime Washington was a boom town,

but few economic benets trickled down to its black residents. Between the spring of

29

OR, ser. 3, 3: 374, 381, 682–83; James M. Paradis, Strike the Blow for Freedom: The 6th

United States Colored Infantry in the Civil War (Shippensburg, Pa.: White Mane Press, 1998),

pp. 9–11; J. Matthew Gallman, Mastering Wartime: A Social History of Philadelphia During the

Civil War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 45, 47–48; James W. Geary, We

Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1991),

p. 9; Russell L. Johnson, Warriors into Workers: The Civil War and the Formation of Urban-

Industrial Society in a Northern City (New York: Fordham University Press, 2003), pp. 245–47,

250–51, 267–72; Thomas R. Kemp, “Community and War: The Civil War Experience of Two New

Hampshire Towns,” in Toward a Social History of the American Civil War: Exploratory Essays,

ed. Maris A. Vinovskis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 38–39; Emma L.

Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 1850–1880 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society,

1965), pp. 177–79.

30

OR, ser. 3, 3: 1085–86; 4: 789. Lt Col L. Wagner to Maj C. W. Foster, 6 Jan 1864 (W–29–

CT–1864); 18 Feb 1864 (W–154–CT–1864); 9 Mar 1864 (W–244–CT–1864); all in Entry 360, RG

94, NA.

31

Edward A. Miller, Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois: The Story of the Twenty-ninth U.S.

Colored Infantry (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998), pp. 12–28; Versalle F.

Washington, Eagles on Their Buttons: A Black Infantry Regiment in the Civil War (Columbia:

University of Missouri Press, 1990), pp. 12–13, 18–26.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

313

1863 and the end of the war, black Washingtonians provided the Union Army with

3,269 soldiers.

32

In a city where federal authorities had arrested the mayor as a Confederate sym-

pathizer during the early months of the war, other civic leaders had to assume the bur-

den of launching a movement for black enlistment. In April 1863, two white military

chaplains assigned to hospitals in Washington suggested in letters to President Lincoln

that they could raise a black regiment in the city and lead it themselves; but not un-

til a 29-year-old minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Henry McNeal

Turner, sponsored several mass meetings in May did the project gather momentum. As

recruits joined, companies of the 1st USCI mustered in during May and June. That fall,

when the regiment was serving in Virginia, Turner became its chaplain.

33

Since Washington was a loyal city with a majority of free people in its black popu-

lation, recruiters for the 1st USCI could not use the press-gang methods that character-

ized Union recruiting in the Mississippi Valley and elsewhere in the occupied South.

32

U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of the Population of the United States (Washington, D.C.:

Government Printing Ofce, 1872), p. 97; Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the

Rebellion (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959 [1909]), p. 11; Constance M. Green, The Secret City:

A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capital (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967),

pp. 61–64, 81–84; James Borchert, Alley Life in Washington: Family, Community, Religion, and

Folklore in the City, 1850–1970 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980), pp. 40–41.

33

OR, ser. 2, 2: 229, 596–99; C[arroll] R. Gibbs, Black, Copper, and Bright: The District of

Columbia’s Black Civil War Regiment (Silver Spring, Md.: Three Dimensional Publishing, 2002),

pp. 32–39.

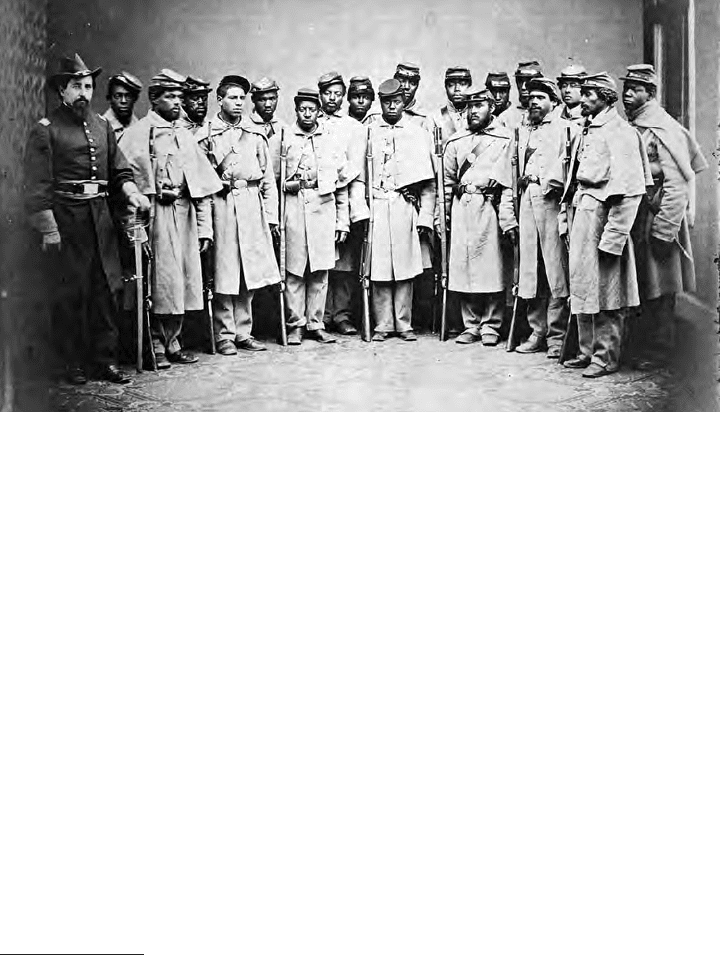

A range of emotions from uncertainty to truculence plays on the faces of these

Philadelphia recruits in early 1864. Their regiment, the 25th U.S. Colored Infantry,

sailed soon afterward for the Gulf of Mexico, where it formed part of the garrison of New

Orleans, and later of Pensacola.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

314

The regiment took nearly two months to ll its ranks, but this was no longer than the

time needed to recruit the rst black regiments in other Northern and border-state cities

during the summer of 1863. Despite antagonism from many white residents in places

like Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Washington, black regiments during the third sum-

mer of the war were able to organize as quickly as many white volunteer regiments had

done in 1861 and 1862, when enthusiasm for the war was high.

34

The streets of Washington provided a setting for the kind of rowdiness and vio-

lence that typify boom towns. In July 1863 alone, city police arrested 1,647 soldiers,

nearly all of them white, mostly for absence without leave, drunkenness, and dis-

orderly behavior. Many white civilian residents were new arrivals who worked for

the Army or Navy and competed directly for jobs as laborers and teamsters with

black Washingtonians and escaped slaves. These white workers displayed a hostil-

ity toward black recruiting that often took physical, even brutal, forms. The murder

and arson that characterized the New York Draft Riots in July were only extreme

examples of the hatred directed at black people that ourished in American cities at

the middle of the nineteenth century. In Washington, an act of Congress had abol-

ished slavery eight months before the Emancipation Proclamation. With that, black

people lost their cash value and their lives became worth nothing in the eyes of many

white rufans. Racially inspired assaults among civilians occurred several times a

week during the summer of 1863, and individual black soldiers in town also suffered

insults and beatings. As companies of the 1st USCI mustered in, military authorities

withdrew them to Analostan Island (since renamed Theodore Roosevelt Island), less

than two miles due west of the White House and just south of Georgetown.

35

An urgent call for protection from the chaplain who commanded one of the

Washington contraband camps brought two companies of the regiment back to

the mainland. At the beginning of June, the camp had suffered an attack by rioters

whom the Evening Star described as “a disorderly gang.” White troops from the

city’s garrison went to New York in mid-July to help suppress the Draft Riots, leav-

ing the camp without an armed guard. The camp chaplain heard remarks “freely

uttered by the rowdy class” that “threatened outbreaks of popular violence here

similar to those so recently occurring in New York,” and asked for a guard from

“the colored regiment” and 150 muskets to arm able-bodied male residents of the

camp. Two companies arrived within a few days, and stood guard over the camp

while the regiment received its last recruits. The 1st USCI sailed for North Caro-

lina at the beginning of August, after a review by Maj. Gen. Silas Casey, a veteran

of the Mexican War and Indian campaigns on the Pacic Coast who chaired the

examining board that met in Washington to evaluate ofcer applicants for the U.S.

Colored Troops. The old soldier observed cautiously that the new regiment looked

34

NA Microlm Pub M594, Compiled Rcds Showing Svc of Mil Units in Volunteer Union

Organizations, roll 205, 1st USCI; (Washington) Evening Star, 5 May 1863; Edward G. Longacre,

A Regiment of Slaves: The 4th United States Colored Infantry, 1863–1866 (Mechanicsburg, Pa.:

Stackpole Books, 2003), pp. 13, 19, 28; Paradis, Strike the Blow for Freedom, pp. 5, 9, 11, 22–23,

29–31; Washington, Eagles on Their Buttons, p. 12.

35

Arrest statistic is in (Washington) Evening Star, 3 August 1863. Incidents of insult and assault

offered to black soldiers are issues for 22 May and 5, 12, and 23 June 1863. Iver Bernstein, The New

York City Draft Riots: Their Signicance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil

War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 27–31.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

315

as well as any body of white troops who had been in the service for the same length

of time.

36

The District of Columbia lay between two slave states. Maryland had never se-

ceded, and federal troops had occupied the Virginia shore of the Potomac during the

rst weeks of the war. Both sides of the river were thus under Union occupation and

exempt from the provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation. Since the federal

capital’s rail links north and west ran through Maryland, the Lincoln administra-

tion tried carefully to avoid measures that would increase the inuence of the state’s

secessionist minority, a group that the mustering ofcer for U.S. Colored Troops in

Baltimore called “vindictive and dangerous.” Not until early October 1863 did the

Adjutant General’s Ofce issue condential orders to govern black enlistments in

Maryland, Missouri, and Tennessee. (At this point in the war, the federal government

was still too cautious to attempt raising black troops in Kentucky.)

37

The rst black regiment raised in Maryland mustered in at Baltimore, becoming

the 4th USCI. Its colonel was Samuel A. Duncan, formerly an ofcer of the 14th

New Hampshire. Entering the Army in the summer of 1862, Duncan was disap-

pointed to spend his rst year in garrison duty at Washington and hoped for active

service with the U.S. Colored Troops. His new regiment’s march through Baltimore

in September 1863 “did much . . . to soften the prejudice against col[ore]d troops—

nowhere stronger, perhaps, than here,” he told his mother.

I have certainly no desire to return to my old regt. I am, in fact, almost con-

vinced that a negro regt. is preferable to a white one—you are under no obliga-

tions to associate with the men—are an entire stranger to them, and of course

they expect to know their Col. as an ofcer only—in consequence of which a

much better discipline is possible among them than if you were obliged to hu-

mor your men on the score of old acquaintance.

Duncan thought that discipline suffered in white volunteer regiments, where most

of the ofcers and men in any company came from the same town or county.

38

The three most eligible kinds of recruit for black regiments in Maryland were

free men; slaves who could show written consent from a loyal master; and slaves of

disloyal masters, who could enlist without permission. Only when these categories

failed to provide enough men did the rules allow recruiters to accept slaves of loyal

masters without permission or to employ the harsh methods that they used com-

monly in the occupied South.

Since slaves would gain their freedom when they entered the Army, each one,

whether enlisting with or without consent, would bring a loyal master three hun-

dred dollars’ compensation from the federal government. This was a bargain for

36

Chaplain J. I. Ferree to Brig Gen J. H. Martindale, 20 Jul 1863 (“freely uttered”), and to Capt

J. E. Montgomery, 22 Jul 1863 (“threatened”), both in Entry 646, Military District of Washington

(MDW), LR, pt. 2, Polyonymous Successions of Cmds, RG 393, Rcds of U.S. Army Continental

Cmds, NA; MDW, Special Order 172, 24 Jul 1863, Entry 649, MDW, Special Orders, pt. 2, RG 393,

NA; (Washington) Evening Star, 2 June 1863; New York Tribune, 23 July 1863.

37

OR, ser. 3, 3: 860–61, 882 (quotation).

38

S. A. Duncan to My Dear Mother, 21 Sep 1863, Duncan-Jones Family Papers, New Hampshire

Historical Society, Concord.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

316

Maryland slaveholders, for human beings had declined sharply in value after the

Emancipation Proclamation. At an estate sale in Rockville that May, the Evening

Star noted, “negroes sold at remarkably low prices.” Thirteen of them, “for the

most part likely young boys,” fetched a sum “less than one thousand dollars.” Two

months later, after Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Port Hudson,

seven “likely, full-grown young negroes brought in all one hundred and twenty-six

dollars, an average of only eighteen dollars a head,” according to a report that ap-

peared in several Northern newspapers. Toward the end of the year, a slaveholder

in Charleston, West Virginia, offered to sell the Army ve “stout active ne looking

men. . . . I will take less than one half of . . . what they would have sold for previous

to this rebellion.” With federal armies moving forward all across the South, human

property was becoming a poor nancial risk and the Army was likely to offer own-

ers the best bargain.

39

Despite the War Department’s attempt to impose order on black enlistments

in the border states, voluntary enlistments soon declined. By that fall, as a result,

recruiting in Maryland had become as rough and tumble a business as it was any-

where else in the South. Boarding oyster boats in Chesapeake Bay, 2d Lt. Joseph

M. Califf and a squad of men from the 7th USCI “knocked at the cabin door—

‘Captain—turn out your crew’—As soon as they came on deck, asked each one—

‘Are you a slave’—‘Yes sir’—‘Get into that boat.’ . . . There was a ne fellow on

board who said he was free,” Califf wrote in his dairy.

I left him, but when I had pushed off, one of the recruits told me he was a

slave—I returned, but he still persisted and the Captain said he would take his

oath, he was free. I left again, but the boys still said he was lying to me and told

me his Master’s name. I returned a second time, . . . jumped down into the hold,

and heard something rattling among the oyster shells. I called for a light, when

I found the fellow, crawled back on the oysters. I had him into my boat in short

order. . . . During the day we got over 80 men.

Energetic recruiters brought in 1,372 men during November, lling Maryland’s

second and third black regiments, numbered the 7th and 9th USCIs.

40

Enough opposition to black enlistment existed to make it a risky business for

both ofcers and recruits. When free black farmers signed on, white neighbors

sometimes removed the fence rails that surrounded their cornelds, allowing

livestock to ravage the crops. The arrest of a civilian recruiting agent in Frederick

was complicated by his lack of military status, which made it more difcult for

military authorities to work for his release. Other agents faced threats of legal

action and physical harm. Far more serious was the death in tobacco-producing

Charles County of 2d Lt. Eben White, 7th USCI, at the hands of two slavehold-

39

OR, ser. 3, 3: 861; (Washington) Evening Star, 12 May 1863 (“negroes sold”). The Associated

Press story appeared in the New York Times and Philadelphia Inquirer on 31 July 1863 and the New

York Tribune on 4 August 1863. J. T. Caldwell to Secretary of War, 10 Nov 1863 (“stout active”)

(C–339–CT–1863), Entry 360, RG 94, NA.

40

J. M. Califf Diary typescript, 29 Nov 1863 (quotation), Historians les, U.S. Army Center of

Military History; Rpt, Col W. Birney, 3 Dec 1863 (B–648–CT–1863, f/w B–40–CT–1863), Entry

360, RG 94, NA.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

317

ers, father and son. The father called White a “Damned Nigger-stealing son of a

bitch,” and the son spat in his face; each red at him, the father with a shotgun,

the son with a revolver. Another shotgun blast took off the hat of Pvt. John W.

Bantum, who accompanied White, and lodged a few birdshot pellets in his scalp.

Bantum ran for his life and took news of White’s death to his captain. The killers

escaped to Virginia. When another ofcer of the recruiting detail rode forty miles

to the Union garrison at Point Lookout to report the murder, the commanding

ofcer’s response expressed a frustration common to ofcers attempting to keep

order in an occupied but hostile country: “Jesus Christ, we have vety miles to

Gaurd [sic] and but Three Hundred men to do it with.”

41

By the late fall of 1863, black regiments raised in Maryland and the North

were serving either along the coast of Florida and South Carolina in the Depart-

ment of the South or around the mouth of the James River in Virginia. Anticipat-

ing a Confederate move in Virginia, General Foster had withdrawn troops from

his North Carolina garrisons in August to reinforce the federal military and naval

bases at Norfolk and Portsmouth. On the north bank of the James, forays by

enemy cavalry trying to gather conscripts for the Confederate Army could cause

what the local Union commander called “a general skedaddle” among white

residents of the peninsula between the James and the York. Such raids had to be

deterred, if not stopped entirely. By the third week of November, the 4th USCI,

the rst of Maryland’s black regiments, and the 6th USCI, the second black regi-

ment organized at Philadelphia, were camped near Yorktown on the peninsula.

At Portsmouth and Norfolk were the 1st USCI, which had arrived in September

after a brief posting to North Carolina; the 5th, from Ohio; and the 10th, orga-

nized in Virginia. There, too, were the 2d and 3d North Carolina Colored, both

regiments still striving to ll their companies. Wild’s three North Carolina regi-

ments would receive new designations—the 35th, 36th, and 37th USCIs—in the

coming spring. Meanwhile, attempts to enlist black civilians who were already

working for the Army brought ofcers of these regiments into conict with lo-

cal quartermasters and other staff ofcers, and they began to look outside Union

lines for recruits.

42

November brought another change to the Department of Virginia and North

Carolina: Maj. Gen Benjamin F. Butler returned to Fort Monroe, where he had

spent much of the rst spring and summer of the war. He had been without

an assignment since December 1862, when he left the Department of the Gulf.

One of the most prominent pro-war Democrats and a possible vice-presidential

or presidential nominee in the 1864 election, Butler was a man for whom the

Lincoln administration had to nd a place. He took command at Fort Monroe

41

Col W. Birney to Adjutant General of the Army, 20 Aug 1863 (B–128–CT–1863, f/w B–40–

CT–1863), and to Lt Col W. H. Chesebrough, 26 Aug 1863 (B–134–CT–1863, f/w B–40–CT–1863);

W. T. Chambers to Col W. Birney, 22 Aug 1863 (C–134–CT–1863); Capt L. L. Weld to Col W. Birney,

23 Nov 1863 (“Damned”) (B–505–CT–1863, f/w W–151–CT–1863); 1st Lt E. S. Edgerton to Col W.

Birney, 25 Nov 1863 (“Jesus”) (E–51–CT–1863, f/w W–151–CT–1863); all in Entry 360, RG 94, NA.

42

OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 2, pp. 99, 104 (quotation). Capt H. F. H. Miller to Col A. G. Draper, 11

Sep 1863; 2d Lt J. N. North to Col A. G. Draper, 16 Sep 1863; both in 36th USCI, Regimental Books,

RG 94, NA; NA M594, roll 205, 1st USCI, and roll 206, 4th, 5th, 6th, and 10th USCIs; Richard M.

Reid, Freedom for Themselves: North Carolina’s Black Soldiers in the Civil War Era (Chapel Hill:

University of North Carolina Press, 2008), pp. 76, 123, 153.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

318

on 11 November, and General Foster moved ve days later to the Department

of the Ohio, where he replaced General Burnside, whose irresolute leadership

in eastern Tennessee was complicating Grant’s effort to raise the Confederate

siege of Chattanooga. Throughout the war, political considerations served to

prolong the careers of generals who had small military ability but great inuence

in Washington.

43

General Wild had managed by this time to return from South Carolina and

was at Norfolk in charge of Colored Troops in the Department of Virginia and

North Carolina. His command was still known as the African Brigade, although

it had become a mixture of USCI (the 1st, 5th, and 10th) and North Carolina

regiments and even included a detachment from the 55th Massachusetts. Up-

permost in Wild’s mind was the job of lling the ranks of his own incomplete

North Carolina regiments. On 17 November, he ordered Col. Alonzo G. Draper

and two companies of the 2d North Carolina Colored on a recruiting expedition.

Each man was to carry forty rounds of ammunition and three days’ rations. “All

Africans, including men, women, and children, who may quit the plantations,

and join your train . . . are to be protected,” Wild ordered. “Should they bring any

of their master’s property with them, you are to protect that also, . . . for you are

not bound to restore any such property. . . . When you return, march slowly, so as

to allow the fugitives to keep up with you.” White civilians found with rearms

were to be arrested. “Should you be red upon,” Wild went on, “you will at once

hang the man who red. Should it be from a house, you will also burn the house

immediately. . . . Guerrillas are not to be taken alive.” Wild enjoined “strict dis-

cipline throughout. March in perfect order so as to make a good impression, and

attract recruits.”

44

Draper set out that afternoon with 6 ofcers and 112 men—about two-fths

of the entire strength of the skeletal regiment—toward Princess Anne County, be-

tween Norfolk and the ocean. They marched southeast about ten miles and camped

for the night. The next day, they began recruiting, “collecting at the same time,

such colored men, women, and children, as chose to join our party.” The expedition

managed to move another nine miles along the road, but side trips to visit every

crossroads settlement and plantation along the way equaled a march of more than

twice that distance, Draper calculated. On the fourth day out, hearing that guerril-

las were massing in the southern part of the county, the recruiting party made for

the farm of one of their leaders, who was not at home. “Our rations being nearly

exhausted, we . . . supplied ourselves liberally with fresh pork, poultry, and corn”

in the guerrilla’s absence, Draper reported, “taking his two teams for transporta-

tion, and also his servants, who desired to go, and who informed us that [he] and

43

OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 2, p. 447; vol. 31, pt. 3, pp. 145–46, 163, 166. Benjamin F. Butler,

Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major-General Benj. F. Butler (Boston: A. M.

Thayer, 1892), pp. 631–35, and Private and Ofcial Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler

During the Period of the Civil War, 5 vols. ([Norwood, Mass.: Plimpton Press], 1917), 3: 348–49

(hereafter cited as Butler Correspondence). Chester G. Hearn, When the Devil Came Down to Dixie:

Ben Butler in New Orleans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997), pp. 226–30.

44

OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 2, pp. 290, 412, 619; 1st Lt H. W. Allen to Col A. G. Draper, 17 Nov 1863

(quotations), 36th USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA. Wild’s pleas for reassignment are in Col E.

A. Wild to Maj T. M. Vincent, 4 Sep 1863 (W–159–CT–1863, f/w W–9–CT–1863), Entry 360, RG

94, NA, and Col E. A. Wild to Maj T. M. Vincent, 30 Sep 1863, Wild Papers.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

319

forty men had that morning taken breakfast there and started off with the avowed

purpose ‘of giving the black soldiers hell.’”

45

Draper’s men marched warily, always with an advance guard and ankers in

the woods that lined the road. Their practice had been to prepare supper late in the

afternoon and move on to another site before camping for the night. To ward off a

retaliatory attack after their raid on the guerrilla’s farm, they surrounded the camp

that night with a four-foot enclosure of fence rails (destroying several hundred

yards of farmers’ fences). The next morning, they moved on, repairing a bridge the

guerrillas had destroyed and spending the night at a plantation, which they forti-

ed with the expedition’s wagon train. The women and children in the party took

shelter from a heavy rainstorm in the slave quarters while the men slept in barns

and sheds.

On 22 November, Draper decided to capture another notorious guerrilla

leader who was supposed to be nearby and might pay a visit to his family. Leav-

ing the wagons and the black civilians in care of an ofcer and twenty-ve men,

Draper took the remaining ninety-two by a circuitous route that brought them,

soon after sunset, close to the guerrilla’s house. A black resident of the neighbor-

hood led them to a ford where they found a atboat that allowed them to make

part of the nal approach by water. The guerrilla leader did not appear until noon

the next day, and he surrendered only after the men of the 2d North Carolina

Colored shot the hull of his boat full of holes. Also arrested in the course of the

expedition were three Confederate soldiers on furlough and six civilians who

were found with weapons. One of them was reputed to have murdered a Union

soldier; another ran a Confederate post ofce. “Nineteen twentieths of all the

citizens of Princess Anne appear to be the friends and allies of the guerrillas,”

Draper reported. “The blacks are the friends of the Union.” About 475 of them

accompanied the Union troops, “besides many who came in separately.” The

expedition returned to Norfolk on 26 November, having covered more than two

hundred fty miles in nine days.

Not all Union ofcers in southeastern Virginia approved of Draper’s expe-

dition, although it is not clear whether they opposed the enlistment of black

soldiers in principle or were merely alienated by General Wild’s prickly per-

sonality. For whatever reason, the colonel commanding the 98th New York,

stationed at an outpost along the recruiters’ route, sent a subordinate to inter-

view farmers in the wake of what the colonel termed Draper’s “marauding &

plundering expedition.” While the colonel’s cover letter spoke of the recruit-

ing party “having committed the grossest outrages, taking the last morsel of

food from destitute families, grossly insulting defenceless women, . . . steal-

ing horses & otherwise disgracing their colors & cause,” the captain’s report

identied forty-eight farms that he visited along Draper’s route. Twenty-three

householders—nearly half of those queried—reported having lost no property

45

Information in this and the following paragraphs is from Col A. G. Draper to Capt G. H.

Johnston, 27 Nov 1863, 36th USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA. Draper estimated his regiment’s

strength as “about three hundred ofcers and men.” Col A. G. Draper to Maj R. S. Davis, 14 Nov

1863, 36th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. The enemy force that Draper sought was one that even

Confederate authorities referred to as guerrillas. OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 2, p. 818.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

320

and suffered no insults from the troops. Only ve complained of the recruiters’

offensive language or threatening behavior.

46

When the report reached Draper, he questioned the ofcers who had accom-

panied his expedition and received convincing accounts that exonerated them and

their men. In replying to the accusations, Draper admitted that he had found one

group of soldiers looting and had them tied up by the thumbs. He had met the colo-

nel who complained of the recruiters’ conduct only once, Draper said. That was

while he had been questioning some white soldiers whom he found slaughtering

poultry in a farmyard. They explained that the farmer’s wife had refused to sell to

Yankees; moreover, these soldiers belonged to the 98th New York, the accusing

colonel’s own regiment. Draper must have relished including that detail, for he

saved it until the end of his letter and used it as the climax of the story. Whatever

troops were responsible for the dead chickens, the fact that his own men had man-

aged to remove food, draft animals, and wagons from barely half of the farms

along their route should have disposed of the complaint that he had run a “maraud-

ing & plundering expedition.” Draper’s account of the expedition did not mention

how many recruits it secured, but they probably numbered fewer than one hundred.

While General Wild’s order directed that the “able-bodied men” would go into the

Army, adult males accounted for less than one-fth of the 475 slaves who escaped

and joined the column.

47

Soon after Draper’s return, Wild began organizing another expedition.

“Our navigation on the Dismal Swamp Canal had been interrupted,” cutting

off federal bases in Virginia from those in North Carolina, “and the Union

inhabitants [of coastal North Carolina have been] plundered by guerrillas,”

General Butler explained to Secretary of War Stanton. On 5 December, eleven

hundred men of the 1st USCI and the 2d North Carolina Colored marched out

of Portsmouth, heading south by way of the canal. At the same time, 530 men

of the 5th USCI left Norfolk, along with another hundred from detachments of

the 1st North Carolina Colored and the 55th Massachusetts. The two columns

met at Camden Court House, North Carolina, and continued on to Elizabeth

City, where two steamboats delivered supplies. “The guerrillas pestered us,”

reported Wild, who hanged the only one his troops caught alive. During the

expedition, Union troops frequently exchanged shots with Confederate irregu-

lars, killing or wounding at least thirteen of them while suffering twenty-two

casualties of their own. Besides that, “many [were] taken sick by fatigue and

exposure, 9 with small-pox, many with mumps.” The nineteen-day expedition

may have released as many as 2,500 slaves, but few recruits were among them.

As Wild wrote, “the able-bodied negroes have had ample opportunities for es-

cape heretofore, or have been run over into Dixie” to labor far beyond the reach

of Union raiders. Butler praised the energy of Wild and his men but admitted

that Wild may have “done his work . . . with too much stringency.” He felt

46

Lt Col F. F. Wead to Capt H. Stevens, 27 Nov 1863 (quotations); Capt J. Ebbs to Lt Col F. F.

Wead, 24 Nov 1863; both in 36th USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA. For Wild’s disagreements

with the commander of the Portsmouth garrison, see OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 2, pp. 542–43, 562.

47

Col A. G. Draper to Maj R. S. Davis, 4 Jan 1864; 1st Lt H. W. Allen to Col A. G. Draper, 17

Nov 1863 (“able-bodied”); and Capt J. Ebbs to Lt Col F. F. Wead, 24 Nov 1863; all in 36th USCI,

Regimental Books, RG 94, NA; Ebbs to Wead, 24 Nov 1863.