Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

291

stopped the skirmishers, the 17th and 44th rushed the Confederate trenches and

captured them. They then pushed on as far as the Nashville and Chattanooga Rail-

road tracks, where artillery re stopped them. While these regiments were pressing

forward, Morgan ordered two white battalions to attack the trenches just west of

those that his own troops had just taken. One battalion, made up of veterans from

ve Ohio regiments, succeeded; but the other, “mostly new conscripts, convales-

cents, and bounty jumpers,” according to its brigade commander, ran headlong to

the rear. Morgan found that he had misjudged Confederate strength and withdrew

his regiments to a less-exposed position from which they sniped at the enemy until

dusk. Smith’s attack on the Confederate left began about three hours after Mor-

gan’s and continued through the day, advancing more than a mile and capturing 36

cannon and 5,123 prisoners. During the night, the survivors of Hood’s army retired

to another line a mile or two south of their position that morning. “The enemy had

been deceived,” Morgan reported, “and, in expectation of a real advance upon his

right, had detained his troops there, while his left was being disastrously driven

back.”

87

Soon after daybreak on 16 December, skirmishers of the 13th USCI moved

forward past the previous day’s corpses “all stripped of their clothing and left upon

the open eld,” as one ofcer reported. They found the Confederate trenches emp-

ty. The rest of Colonel Thompson’s brigade followed, moving almost due south for

two miles, ahead of the rest of Steedman’s command. By early afternoon, Steed-

man, at the east end of the Union line, was in touch with the headquarters of IV

Corps, on his right, and preparing to support the main attack on the new Confeder-

ate position. Thompson’s brigade would lead, along with a brigade of white troops

that included the battalion that had “stampeded” the day before. The 18th USCI

had reinforced that brigade since the previous day’s attack.

88

Steedman’s line started forward about 3:00 p.m. On the left, the 12th USCI had

to move in column to get past some dense undergrowth. When it passed the thicket

and opened from column into line, its rapid movement led ofcers of the 13th and

100th to think that Colonel Thompson had ordered a charge and those regiments

began to advance at a run. “Being under a heavy re at the time,” Thompson re-

ported, “I thought it would cause much confusion to rectify this, so I ordered the

whole line to charge.” Felled trees and the angle of the Confederate works split the

12th and half of the 100th from the other half of the 100th. Confederate re tore

into both bodies of men. Colonel Hottenstein, some distance behind with the 13th

USCI, saw that “the troops in our front began to lie down and skulk to the rear,

which, of course, was not calculated to give much courage to men [of the 13th]

who never before had undergone an ordeal by re.” On their left, the battalion of

“conscripts, convalescents, and bounty jumpers” ran away again and its brigade

commander “saw it no more during the campaign.” The rest of the brigade—the

18th USCI and two veteran white battalions—pressed forward but failed to hold a

position close to the Confederate line. The 13th USCI nally pushed through the

disordered 12th and 100th and reached the enemy defenses; but it soon retreated,

87

OR, ser. 1, vol. 45, pt. 1, pp. 433, 436, 527 (“mostly new”), 531, 536 (“lay like”), 539; Dyer,

Compendium, p. 1505; McMurry, John Bell Hood, p. 179.

88

OR, ser. 1, vol. 45, pt. 1, pp. 527 (“stampeded”), 528 (“all stripped”), 543, 548.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

292

joining the survivors of the brigade near where the afternoon’s attack had begun.

Thompson’s brigade had lost 80 ofcers and men killed and 388 wounded in less

than half an hour, by far the highest loss in any Union brigade that day.

89

By the time Thompson had withdrawn his men from the east end of the Con-

federate line, General Smith’s brigades were attacking the other end, as they had

the day before. Their assault succeeded, and the Confederate division that had just

defeated Steedman’s regiments and “was thus in the highest state of enthusiasm,”

its commander reported, soon “saw the troops on [its] left ying in disorder” and

had to join the retreat. “Rebs were seen running in every direction a perfect rout,”

Lieutenant Hall of the 44th USCI wrote to his mother. Steedman’s troops and those

of the IV Corps, which had also failed to take its objective that afternoon, collected

themselves and followed the enemy south on the road toward Franklin. “Began

raining in the afternoon & continued all evening,” 2d Lt. Henry Campbell of the

101st USCI entered in his journal. “Troops too tired to follow the rebels far.”

90

Night fell as Steedman’s two brigades of U.S. Colored Troops, along with the

IV Corps, pursued the Confederates. They bivouacked about eight miles south of

Nashville and continued the pursuit the next day, reaching Franklin in the early af-

ternoon. There they found that the retreating Confederates had burned the bridges

across the Harpeth River. Since their rapid advance had left the pontoon train far

behind, they had to wait while a regiment of the IV Corps built a new bridge. Rain

began to fall again on 18 December, making it impossible for troops to advance

through the elds on either side of the highway. Steedman’s two brigades, about

three miles beyond Franklin and headed south, received orders that morning to turn

around and march to the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad at Murfreesborough,

thirty miles east of Franklin. They arrived on 20 December. From there, trains took

them southeast to Stevenson, Alabama, then west toward Decatur, where some of

the men had begun the campaign two months earlier. The object of their movement

was to secure the Tennessee River crossing before the remains of Hood’s army

could reach it. The rest of General Thomas’ army followed the retreating Confed-

erates by a more direct but slower route along muddy roads through Columbia and

Pulaski, having to wait twice for the pontoon train to bridge swollen rivers.

91

Late in the afternoon of 26 December, Steedman’s troop trains stopped where

the tracks of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad crossed Limestone Creek,

about eight miles east of Decatur. The bridge was out, so the men got off the train

and followed the creek downstream to the Tennessee River. There they met a eet

of ten gunboats and transports with food and forage, which General Thomas had

sent to help intercept the Confederate retreat. The boats ferried Steedman’s force

across the river. Once ashore, the troops had “to wade a deep bayou, deploy as

skirmishers, and protect [the] landing,” an ofcer of the 12th USCI recorded. “In

wading bayou some men got out of their depth, none lost—slight skirmish.” A few

shots were enough to oust a weak Confederate cavalry regiment that guarded De-

89

Ibid., pp. 527 (“conscripts”), 528 (“saw it”), 543 (“Being under”), 544, 546, 548 (“the troops”),

698.

90

Ibid., pp. 290–91, 505, 698 (“was thus,” “saw the troops ”); M. S. Hall to Dear Mother, 17 Jan

1865 (“Rebs”), Hall Papers; H. Campbell Jnl, 18 Dec 1864, Wabash College, Crawfordsville, Ind.

91

OR, ser. 1, vol. 45, pt. 1, pp. 135, 159–64, 291, 505, 549, and pt. 2, pp. 260, 325–26.

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

293

catur. By 7:00 that evening, Union troops controlled the town. Two days later, they

learned that Hood’s army had found another crossing some forty miles downstream

and was already south of the Tennessee River on its way to Corinth, Mississippi.

92

When that news arrived, Steedman’s men were marching west toward the

site of Hood’s crossing. Detachments of white Union cavalry that accompanied

them routed the eeing Confederates near a town called Courtland, some twenty

miles west of Decatur, allowing the infantry to reach there without further trou-

ble. On 30 December, a company commander in the 12th USCI noted that “want

of . . . blankets & tents, cold & wet weather, the passage of numerous streams &

the usual hardships of a winter campaign have seriously lessened our numbers &

impaired the efciency of those present. The men . . . are decient in energy on

the march.” Fortunately for the troops, this phase of the campaign was nearing

an end. On New Year’s Day, General Thomas ordered Steedman to break up his

division and return to Chattanooga with Morgan’s brigade, sending Thompson’s

brigade to Nashville.

93

Regimental ofcers saw the lull in active operations as an opportunity to bring

their commands up to strength and devote some attention to discipline and drill.

Lt. Col. Henry Stone, ordered back to the Nashville and Northwestern Railroad,

92

Ibid., pt. 1, p. 506, and pt. 2, pp. 384, 400–403, 698; ORN, 26: 671–82; NA M594, roll 207,

12th USCI (quotation).

93

OR, ser. 1, vol. 45, pt. 2, pp. 401, 480, 493; NA M594, roll 207, 12th USCI (quotation).

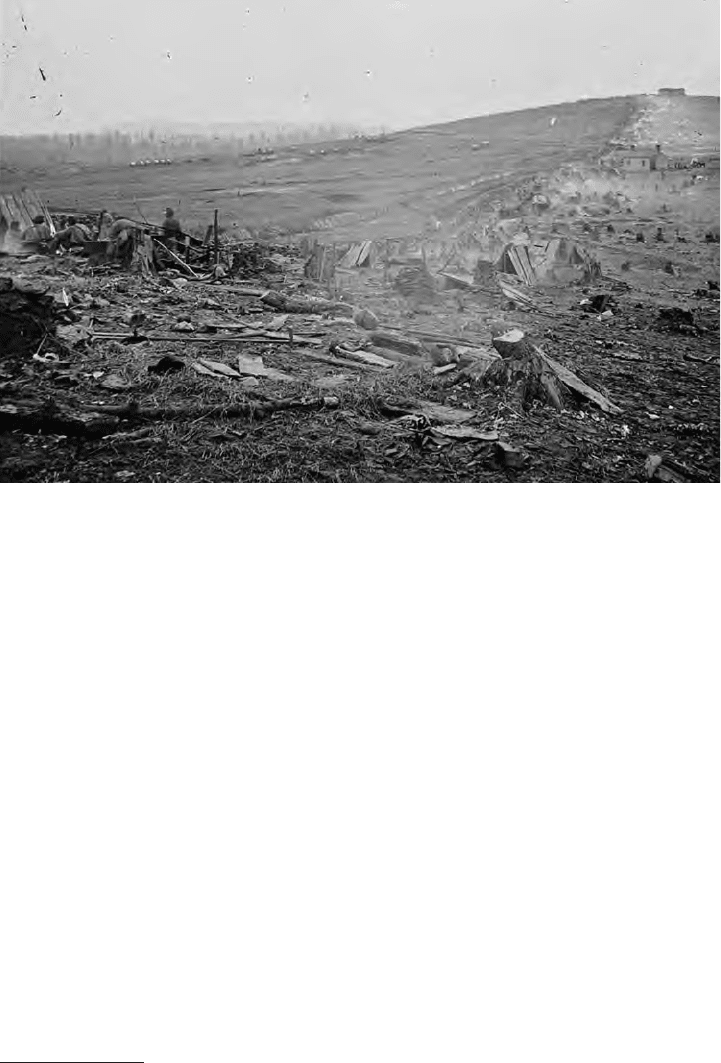

Part of the Nashville battleeld, taken as victorious Union troops pursued retreating

Confederates south of the city

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

294

asked that all the companies of the 100th USCI be stationed together for the rst

time. The regiments at Chattanooga, he pointed out, “have had the good fortune to

be placed in such positions as have given them the facilities” for instruction, and

he asked the same advantages for his own regiment and the others in Thompson’s

brigade. Colonel Thompson agreed with Stone; but General Thomas, who retained

his command because of his victory over Hood, decided that drill was less impor-

tant than guarding the Nashville and Northwestern, which was still a major supply

artery for his army.

94

Guard duty did not mean inactivity. Even in the last months of the war, Con-

federate guerrillas operated widely throughout the Department of the Cumberland.

Field operations began as soon as the troops reached their new stations. The com-

manding ofcer of Company C, 18th USCI, noted “frequent night scouts” near

Bridgeport, Alabama, in late January “to look for guerrillas, who commit depreda-

tions on the citizens.” For the 42d USCI, an “invalid” regiment that General Steed-

man left in Chattanooga during the Nashville Campaign, antiguerrilla duty had

never stopped. One company of the regiment covered an estimated seventy-two

miles in four days during a “short but severe campaign” in early January against

Confederate irregulars who had red on a party of federal soldiers guarding a cat-

tle herd. “My men is very mutch exposed & very badly quartered, besides quite

a number of them sick,” one company commander complained as winter ended.

“They have had no less than ve ghts since the rst day of this month.” On 18

March, “the rebel Colonel” Lemuel G. Mead, who had recruited a force known

as Mead’s Confederate Partisan Rangers in Union-occupied Tennessee, attacked

an outpost of the 101st USCI at Boyd’s Station, Alabama, on the Memphis and

Charleston Railroad, killing ve men of Company E. A few weeks later, as the

Confederacy collapsed, Union troops accepted the surrender of Mead’s men, al-

though one federal ofcer characterized them as “ragamufns, bushwhackers, . . .

horse-thieves, and murderers.”

95

With the close of hostilities, regiments of U.S. Colored Troops in the Depart-

ment of the Cumberland began issuing furloughs to enlisted men for home visits.

Black soldiers in central Tennessee and northern Alabama found themselves closer

to home at the end of the war than did those in most other parts of the conquered

South. For men in the northern and Kentucky regiments of U.S. Colored Troops

who served in Virginia during the war and took ship for Texas soon afterward,

distance prohibited furloughs, as it did for those serving in Florida and around

Mobile. During the war, Memphis and other Mississippi River towns had attracted

black refugees from plantations in the surrounding counties, including the families

of many soldiers in garrison, so that furloughs for troops in garrison there were

not as necessary. Only in the Department of the Cumberland and along the lower

94

Lt Col H. Stone to Brig Gen W. D. Whipple, 16 Jan 1865, f/w 12th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94,

NA.

95

OR, ser. 1, vol. 49, pt. 1, pp. 86 (“the rebel”), 559 (“ragamufns”), 1023; Capt J. H. Hull to

1st Lt A. Caskey, 24 Mar 1865 (“My men”), 101st USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. NA M594, roll

207, 18th USCI (“frequent night”); roll 209, 42d USCI (“short but”); roll 215, 101st USCI. Mead’s

Confederate Partisan Rangers had a short ofcial existence, from March 1865 to the Confederate

surrender. Stewart Sifakis, Compendium of the Confederate Armies, 11 vols. (New York: Facts on

File, 1992–1995), 3: 77.

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

295

Mississippi did large numbers of U.S. Colored Troops nish the war reasonably

near the places where they had enlisted, but still at some distance from their fami-

lies. During their service, most of the Tennesseans had covered the country from

Dalton, Georgia, in the east to Decatur, Alabama, in the west and as far north as

the Kentucky state line. They had left their families behind and felt a strong desire

to see them again.

96

Company commanders would specify the number of men who could request fur-

loughs, the term of the furloughs (usually ten or twenty days), and the purpose: “their

families are residing with their former masters, and these men desire to visit them to

provide for them untill their term of service expires,” was the formula in Company B

of the 110th USCI. Commanding ofcers had authority to extend a furlough because

of sickness, whether of the enlisted man or of one of his relatives.

97

Black soldiers who received furloughs to visit their families often found them

living with their former masters or in the contraband camps established by Union

occupiers at several sites: Nashville, Clarksville, and Gallatin, Tennessee, and

Huntsville, Alabama. Living conditions in the camps had attracted the attention of

War Department investigators as early as the spring of 1864. While touring the re-

gion, inspecting camps and collecting testimony, they learned that residents’ wel-

fare depended almost entirely on the energy and dedication of a camp’s command-

er. The general at Nashville was “culpably negligent,” they reported, while the

chaplain in charge at Huntsville “was wholly devoted to the care of its inmates.”

98

The camp at Clarksville had provided 136 soldiers for the Union Army; the one

at Gallatin, “several hundred.” The investigators’ report made clear the government’s

responsibility toward them. “If we take colored soldiers into our armies, . . . we must

take them under the obligation to take care of the families that would be otherwise

left in want. When the enlisting colored soldiers are assured that the care of their

families shall be the care of the government, that assurance must be made good. If we

exact good faith from them, we must keep good faith with them.” Further, the inves-

tigators recommended establishment of a federal ofce “nominally military, under

the general authority and supervision of the War Department, . . . for this distinct

service.” The U.S. Senate published its report on 27 February 1865.

99

Four days later, Congress passed a law it had been tailoring for more than four-

teen months to “establish a bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees.” The

term refugees applied usually to white Unionists displaced by the ghting; freed-

men generally referred to black Southerners of any age and both sexes, including

those who had been free before the war. Even these latter saw changes in their legal

status as the coming of emancipation and the war’s end swept away many antebel-

lum statutes. An agency of the War Department called the Bureau of Refugees,

96

On the situation in the Department of the Cumberland, see Ira Berlin et al., eds., The

Destruction of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 265, and The Wartime

Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 376–

85. Documentation is missing for most Louisiana-raised U.S. Colored Troops regiments that were

still stationed there at the end of the war.

97

Abstracts 81 and 110 (“their families”) in Letterbook, 110th USCI, Regimental Books, RG

94, NA.

98

“Condition and Treatment of Colored Refugees,” 38th Cong., 2d sess., S. Ex. Doc. 28 (serial

1,209), pp. 9 (“culpably”), 12 (“was wholly”).

99

Ibid., pp. 9, 11 (“several”), 20 (“If we take”), 22 (“nominally”).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

296

Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands

would assume “control of all subjects

relating to refugees and freedmen

from rebel states, or from any district

of country within the territory em-

braced in the operations of the army.”

Its rst concern was the welfare of

“destitute and suffering refugees and

freedmen and their wives and chil-

dren.” As the year wore on, the Bu-

reau’s agents would supervise labor

contracts between former slaves and

white planters, who were no longer

slaveholders but still owned most of

the best farmland.

100

In July 1865, the 14th USCI had

six men on furlough and nine appli-

cations pending when the regimental

commander asked permission for

three of his soldiers to attend “the

Convention of Colored People of this

State” at Nashville the next month.

Garrison and district headquarters

approved the soldiers’ request. Many

black Southerners were aware of im-

pending political changes that would

affect their future and sought to in-

uence the results by exercising their

new rights to petition and to assem-

ble peaceably.

101

The convention met on 7 August

at a chapel of the African Method-

ist Episcopal Church. Twenty of the

116 delegates were soldiers in Ten-

nessee regiments of the U.S. Colored

Troops. Sgt. Henry J. Maxwell of

Battery A, 2d USCA, addressed them

on the rst day. “We want the rights

guaranteed by the Innite Architect,”

he told them. “We have gained one—

100

U.S. Statutes at Large, 13: 507–08; Ira Berlin et al., eds., The Wartime Genesis of Free

Labor: The Lower South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 373–74. H. R. 51,

introduced on 14 December 1863, originally called for a “Bureau of Emancipation.” Congressional

Globe, 38th Cong., 1st sess., 134: 19.

101

Lt Col H. C. Corbin to Brig Gen A. J. Alexander, 19 Jul 1865 (“the Convention”), 14th USCI,

Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. See also “Petition of the Colored Citizens of Nashville,” 9 Jan 1865, in Berlin

et al., Black Military Experience, pp. 811–16.

Sgt. Henry J. Maxwell,

2d U.S. Colored Artillery

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

297

the uniform is its badge. We want two more boxes, beside the cartridge box—the

ballot box and the jury box.” The convention adjourned four days later, resolving

to work closely with agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau and to attempt a census of

“our people” in the state. The soldiers returned to their regiments. For the next

two years, helping to enforce the edicts of the Freedmen’s Bureau and assisting its

agents would take up most of the time of U.S. Colored Troops in Tennessee and

other parts of the occupied South.

102

102

Colored Tennessean (Nashville), 12 August 1865.

R

o

a

n

o

k

e

R

A

l

b

e

m

a

r

l

e

S

o

u

n

d

P

A

M

L

I

C

O

S

O

U

N

D

J

a

m

e

s

R

J

a

m

e

s

R

P

o

t

o

m

a

c

R

T

a

r

R

P

a

m

l

i

c

o

R

N

e

u

s

e

R

C

a

p

e

F

e

a

r

R

C

H

E

S

A

P

E

A

K

E

B

A

Y

Y

o

r

k

R

C

h

i

c

k

a

h

o

m

i

n

y

R

M

a

t

t

a

p

o

n

i

R

P

a

m

u

n

k

e

y

R

R

a

p

i

d

a

n

R

R

a

p

p

a

h

a

n

n

o

c

k

R

S

t

a

u

n

t

o

n

R

Dismal Swamp

Canal

Cape Fear

Cape Lookout

Cape Hatteras

Cape Charles

Point Lookout

Fort Fisher

Fort Monroe

Florence

Goldsborough

Beaufort

Tarboro

Gaston

Kinston

Faison’s

Station

Bentonville

Cox’s Bridge

Washington

Plymouth

Elizabeth City

Camden

Court House

Clinton

Henderson

Greensboro

Chapel Hill

Appomattox

Court House

Portsmouth

Hampton

Yorktown

Glouscester Point

Charles City Court House

New Kent Court House

King and Queen

Court House

City Point

Spotsylvania Court House

Staunton

New Market

Manassas Junction

Port Tobacco

Harpers Ferry

Romney

Salisbury

Fayetteville

Petersburg

Lynchburg

Charlottesville

Fredericksburg

Alexandria

Frederick

Baltimore

Norfolk

Wilmington

New Berne

Danville

RALEIGH

RICHMOND

ANNAPOLIS

WASHINGTON

DOVER

VIRGINIA

WEST

VIRGINIA

DELAWARE

MARYLAND

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

NORTH

CAROLINA

SOUTH

CAROLINA

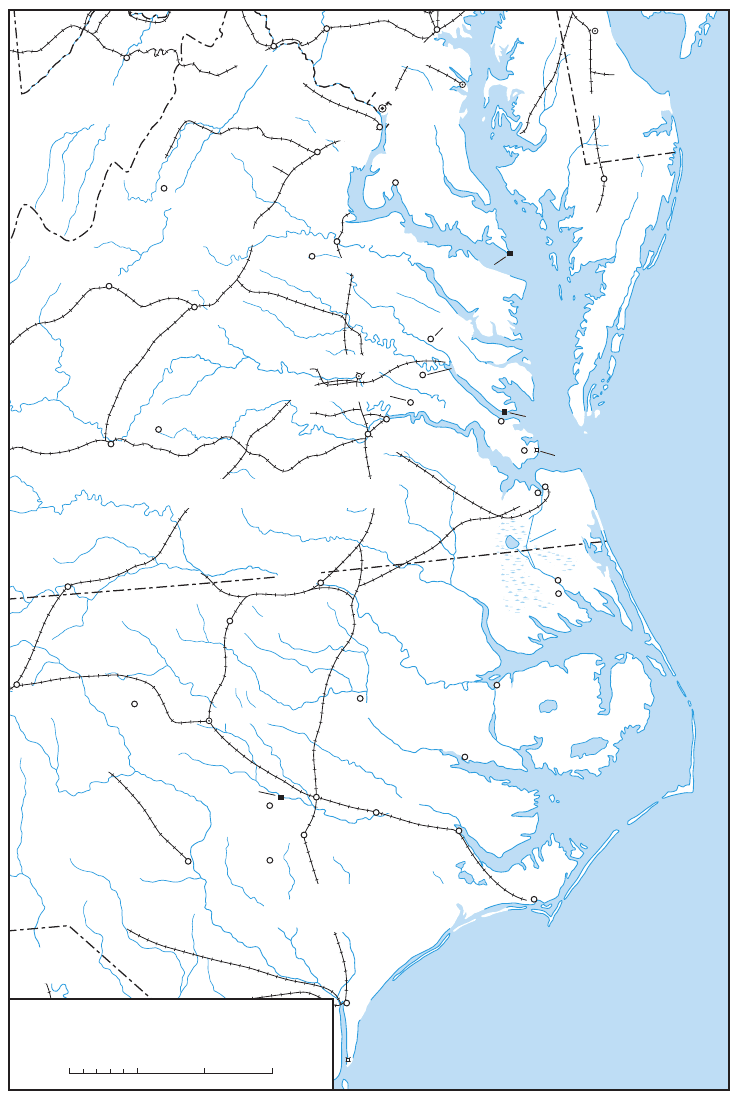

NORTH CAROLINA AND VIRGINIA

1861–1864

0

755025

Miles

Map 7

When the Confederate Congress, meeting in Montgomery, Alabama, voted on 20

May 1861 to move the seat of government east to Richmond, Virginia, it altered drastical-

ly the shape of the impending conict. Suddenly, the capitals of the contending govern-

ments lay only a few days’ march apart. Both sides massed their principal armies in this

comparatively small space, where they struggled back and forth across the same terrain

for four years. The concentrated drama and violence of this contest, conducted close to

major communications centers and millions of newspaper readers, often overshadowed

events in other parts of the country. Nevertheless, Union armies in the Mississippi Valley

and in scattered coastal enclaves continued to follow the broad outlines of the scheme

set forth by Lt. Gen. Wineld Scott during the rst spring of the war (see Map 7).

1

Learning of the secessionists’ plan to move their capital and unsatised with the

slow progress that Scott’s “Anaconda” promised, Northern editors at once began urg-

ing the federal government to capture Richmond before the Confederate Congress con-

vened there in July. A headline in Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune exhorted: “To

Richmond! To Richmond! Onward!” Military authorities at Washington took a much

more cautious view, but they wanted to get some use out of the regiments that had

responded to the president’s summons, for the militia’s three-month term of service

would expire in mid-July. To this end, they organized a three-pronged sweep intended

to drive Confederate troops from the Virginia counties along the Potomac River, where

they threatened the federal capital and its link to the West, the Baltimore and Ohio Rail-

road. The Northern press misinterpreted this operation as the long-awaited offensive.

“The Army is in motion, . . . advancing upon Richmond . . . that centre of rebellion,” the

New York Times reported. The movement ended in disaster on 21 July at Manassas, just

thirty-ve miles—a day’s brisk retreat, as it turned out—from Washington. The Union

Army returned to the capital; the militia regiments went home; and volunteers, enlisted

for three years’ service, began arriving to take their place.

2

The defense of Washington was uppermost in the mind of Maj. Gen. George

B. McClellan when he arrived later that summer to take charge of the volunteer

regiments that were gathering there. He formed them into brigades and divisions

1

Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865, 58th Cong., 2d

sess., S. Doc. 234, 7 vols., serials 4,610–4,616, 1: 254–55.

2

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Ofcial Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies, 70 vols. in 128 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1880–1901), ser. 1, 2: 709,

North Carolina and Virginia

1861–1864

Chapter 10

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

300

and called his new command the Army of the Potomac. Country roads outside the

city were so bad that the troops received supplies, whenever possible, by boat.

“Not less than twenty of my teams are on the road struggling to work their way

through the mud,” Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker reported from southern Maryland in

early November. “If this should be continued, I shall not have a serviceable team

in my train, nor will the depot quartermaster in Washington if he permits his teams

to be put on the road.” Hooker thought of withdrawing his troops from southern

Maryland—a tobacco-growing region full of slaveholders and Confederate sym-

pathizers—to a point closer to the federal supply railhead in Washington. Since

each side tried to use artillery re to interdict the other’s shipping, control of the

shoreline was clearly necessary to secure the defenses of the capital.

3

While the garrison of Washington reorganized and gathered strength, ships of

the U.S. Navy patrolled Chesapeake Bay and the rivers emptying into it. Slaves

from the Tidewater counties of Virginia, sometimes entire families of them, took to

boats and made their way to these vessels, which put them ashore at Washington or

Fort Monroe. There, those who were able to work found employment with Army

quartermasters. Confederate authorities, of course, took a different view of the

matter. At Yorktown, one Virginia general complained in mid-August that “from

$5,000 to $8,000 worth of negroes [were] decoyed off” each week.

4

Some of the more enterprising and politically connected Union generals

sought independent commands that summer, rather than spend the rest of the

year camped near Washington, helping to train McClellan’s army. Maj. Gen.

Benjamin F. Butler, who took charge of the maritime expedition that captured

New Orleans the following spring, was one; another was Brig. Gen. Ambrose

E. Burnside, a Rhode Islander who had graduated from West Point in 1847, one

year after McClellan. Burnside proposed raising a marine division of ten New

England regiments with shallow-draft boats to secure the Potomac estuary and

Chesapeake Bay. The War Department approved the plan, but by January 1862,

when Burnside was able to gather the troops, McClellan had been appointed to

the command of all Union armies and used his new authority to order Burnside’s

force to North Carolina. The object of the expedition was to land on the coast,

to penetrate inland as far as Goldsborough, and there to cut an important rail

line that ran from the deepwater port of Wilmington, in the southeastern corner

of the state, north to Richmond, carrying supplies to the Confederate army that

threatened Washington. The line was especially useful because it was of uniform

gauge, a rarity in the South, and was thus able to move material rapidly along its

entire 170-mile length.

5

More than 160,000 people lived in the seventeen counties that lined the ser-

rated coastline behind the Outer Banks. The region was home to 68,519 slaves

(42.7 percent of the population) and 8,049 free blacks (5 percent). Of the black

711, 718–21 (hereafter cited as OR); New York Tribune, 30 May 1861; New York Times, 18 July 1861.

3

OR, ser. 1, 5: 372–77, 407–11, 421–24, 643 (quotation).

4

OR, ser. 1, 4: 614, 634 (quotation). Ofcial Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in

the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1894–1922), ser.

1, 4: 508, 583, 598, 681–82, 748; 6: 80–81, 107, 113, 363 (hereafter cited as ORN).

5

OR, ser. 1, 5: 36; Robert M. Browning Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North

Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press,