Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

321

“much indebted to General Wild and his negro troops for what they have done,

and . . . while some complaints are made of the action authorized by General

Wild against the inhabitants and their property, yet all . . . agree that the negro

soldiers made no unauthorized interferences with property or persons, and con-

ducted themselves with propriety.”

48

Just a month after Wild’s expedition returned, one of the participants wrote a

letter that showed how different the war in Virginia had been during its rst three

years from the one waged elsewhere in the South. The nature of Virginia’s agri-

culture—which concentrated on corn, wheat, tobacco, and livestock—meant that

although slaves constituted more than one-third of the population in the Tidewater

and Piedmont regions of the state, most of them lived in two- and three-family

groups, rather than on extensive plantations. The contending armies moved repeat-

48

OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 1, pp. 910–18 (“The guerrillas,” p. 912; “many,” p. 914; “the able-

bodied,” p. 913), and pt. 2, p. 596 (“Our navigation,” “done his work”). Browning, From Cape

Charles to Cape Fear, pp. 124–28; Wayne K. Durrill, War of Another Kind: A Southern Community

in the Great Rebellion (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 145–53.

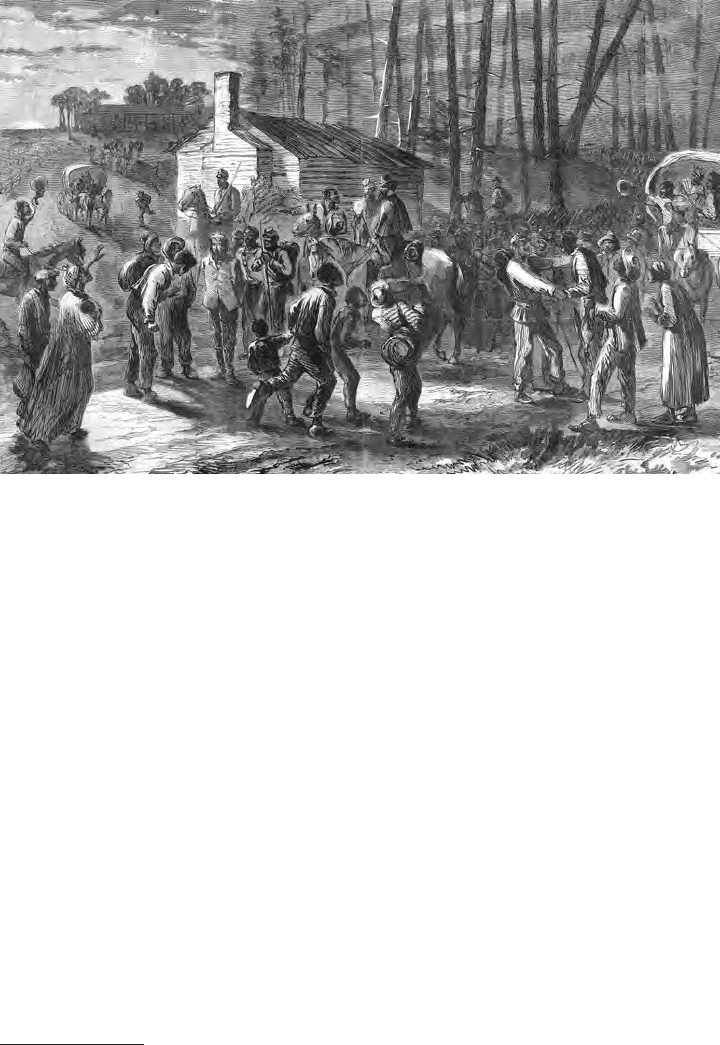

In December 1863, Brig. Gen. Edward A. Wild led more than seventeen hundred

men from ve black regiments through northeastern North Carolina, freeing slaves,

hunting Confederate guerrillas, and enlisting black soldiers. The greeting exchanged

between a soldier and civilian (right foreground) indicates that two of Wild’s

regiments had been raised in North Carolina and knew the country and the people

they were operating among.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

322

edly back and forth across the same narrow stretch of country, concentrating on

each other’s movements rather than on sweeping raids that made it possible for

hundreds of slaves to escape bondage. Each army usually operated within a few

days’ march of its base of supply and did not rely on foraging as often or as com-

pletely as did the western armies.

49

The attitudes of 1st Lt. Elliott F. Grabill of the 5th USCI had been shaped

by two years of such warfare. Grabill joined the Oberlin company of the 7th

Ohio in June 1861 and served with it in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign the

following spring and in all the campaigns of the Army of the Potomac through

the summer of 1863, ending with the occupation of New York City after the

Draft Riots. Appointed to the 5th USCI, he became the adjutant; Lt. Col. Giles

W. Shurtleff, who had been his company commander in the 7th Ohio, became

the regiment’s second-in-command. Grabill came from one of the most fervently

abolitionist towns in Ohio, and having served in the Army of the Potomac, he

did not like what he saw during Wild’s foray into North Carolina. When the

5th USCI moved across the James River and camped near Yorktown, Grabill

condemned the “contraband stealing expedition” in a letter to his ancée, calling

it “a most disgraceful affair.”

In all my experience . . . of army life I have never before seen or taken part

in an expedition of which I was so heartily disgusted. It was a grand thiev-

ing expedition. Our Colonel used every effort to prevent his command from

indulging in this unsoldierly conduct; but when the other troops of the brigade

were permitted almost unbridled license and the General himself gave the

encouragement of example and even on several occasions gave directions to

further . . . such robbery, it was difcult to promote the best of discipline in

our regiment. . . . We were not organized into an armed force for this little

petty stealing. It is subversive of military discipline and makes an army a mob

with all its elements of evil. . . . In Gen. Wilds Brigade we were with N.C.

Colored Vol[unteer]s—contrabands picked up . . . on the plantations not re-

markable for intelligence or quickness of discernment and skilful performance

of military duty. Nor were their ofcers of that culture and general knowledge

which the Military Boards of Examination pass. They were appointed on the

mere recommendation of Gen. Wild. We are appointed because we are proven

worthy of appointment by our examination. They are N.C. Volunteers; we are

United States Colored Troops.

Grabill and Col. Robert G. Shaw of the 54th Massachusetts were the same age

(both born in 1837), shared abolitionist convictions, and had served for two years

in Virginia in the body of troops that became the XII Corps of the Army of the

Potomac, Grabill with the 7th Ohio, Shaw with the 2d Massachusetts. A ferocious

49

Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern

Civilians, 1861–1865 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 105–11; Sam B.

Hilliard, Atlas of Antebellum Southern Agriculture (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University

Press, 1984), pp. 34, 36, 49–56, 61–62, 66–67, 76; Lynda J. Morgan, Emancipation in Virginia’s

Tobacco Belt, 1850–1870 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992), pp. 19–22, 26–27, 36–

43, 105–06, 111–13.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

323

ghter like Wild caused the same revulsion in Grabill that Col. James Montgomery

of the 2d South Carolina Colored had inspired earlier that year in Shaw.

50

Grabill wrote his letter of complaint on the peninsula north of the James River.

The 5th USCI had left Norfolk on 20 January and sailed to Yorktown, on the north

side of the peninsula, where it reinforced the 4th and 6th. Those two regiments had

arrived from Baltimore and Philadelphia in early October. Within a week of its ar-

rival on the peninsula, the 4th USCI took part in a raid across the York River. Ten

gunboats accompanied a transport that bore 744 ofcers and men of the regiment,

500 white cavalrymen and their horses, and 4 artillery pieces to Mathews County,

on Chesapeake Bay. During the next four days, the expedition destroyed about

one hundred fty small craft that the raiders believed might be of use to Confed-

erate irregulars and captured a herd of eighty cattle. The general commanding at

Yorktown, who had not seen black soldiers before, reported favorably: “The negro

infantry . . . marched 30 miles a day without a straggler or a complaint. . . . Not a

fence rail was burned or a chicken stolen by them. They seem to be well controlled

and their discipline, obedience, and cheerfulness, for new troops, is surprising, and

has dispelled many of my prejudices.”

51

Colonel Duncan was pleased with his regiment, the 4th USCI. “The endur-

ance, and the patience of the men, uttering no complaints, was remarkable,” he told

his mother. “On the homeward trip, which was severer than marching out, the men

were shouting and singing most of the way, and upon reaching camp they fell to

dancing jigs.” Duncan thought well of his ofcers, too, “ne, accomplished gentle-

men,” and of the regimental chaplain, a minister of the African Methodist Episco-

pal Church, “Mr. [William H.] Hunter—an able and agreeable and hard working

man—as black as the ace of spades.” Constant fatigues left no time for drill, for

the campsite at Yorktown was lthy after more than two years of occupation, rst

by Confederate and then by Union troops. The arrival of the 6th USCI spared

Duncan’s regiment some of that work. Among the ofcers of the 6th the colonel

recognized two acquaintances from the 14th New Hampshire and soon developed

a close working relationship with their regiment. A month later, after taking part in

another expedition, Duncan’s condence was undiminished. “The colored soldiers

develop remarkable qualities for marching, and I think will be equally brave in

battle. . . . I am perfectly willing to risk my reputation with the negro soldiers.”

52

One of these was Sgt. Maj. Christian A. Fleetwood, a free-born, literate Bal-

timorean who had been among the rst to show an interest in the new regiment

that summer. After putting his affairs in order, the 23-year-old signed his enlist-

ment papers on 11 August. Eight days later, the commanding ofcer appointed

him the senior noncommissioned ofcer of the regiment. A neat appearance,

50

E. F. Grabill to Dear Anna, 23 Jan 1864, E. F. Grabill Papers, Oberlin College (OC), Oberlin,

Ohio; Gerald F. Linderman, Embattled Courage: The Experience of Combat in the American Civil

War (New York: Free Press, 1987), pp. 180–85, 191–201, 211–15; James M. McPherson, For Cause

and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp.

168–76; Charles F. Royster, The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson,

and the Americans (New York: Knopf, 1991), pp. 361–63.

51

OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 1, pp. 205–07 (“The negro,” p. 207); NA M594, roll 206, 4th, 5th, and

6th USCIs.

52

S. A. Duncan to My Dear Mother, 18 Oct 1863 (“The endurance”), and to My Dear Friend, 20

Nov 1863 (“The colored”), both in Duncan-Jones Papers.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

324

good manners, and legible handwriting were among the chief qualications for

a sergeant major. Fleetwood kept a diary, but the entries were always laconic. Of

the raid to Mathews County, he recorded only “weather ne for marching.” He

and the other senior noncommissioned ofcers of the 4th USCI quickly estab-

lished social relations with the noncommissioned staff of the 6th when that regi-

ment reached Yorktown on 18 October. “Singing[,] dominoes & c.,” Fleetwood

wrote the next day, and eleven days later: “N.C.S. [Non Commissioned Staff] of

6th over to our social. Bully time.” Close, informal acquaintance between senior

noncommissioned ofcers within a brigade could foster cooperation in camp and

in the eld.

53

Morale was high among the new arrivals. “There has sprung up quite a rivalry

between this regiment & the fourth,” 2d Lt. Robert N. Verplanck wrote to his sister

from the 6th USCI camp,

each one trying to outdo the other in drill, guard-mounting and sentinel duty; it

will have very good effect on both, but we are somewhat ahead of the fourth at

present on drill & can not learn a great deal from them. The men of our regiment

are composed of [a] more intelligent class of men & learn quicker. They don’t

seem to mind working on the forts at all but rather to enjoy it for as they work

they are in a continual gale of merriment & do twice as much as white troops.

Despite their skylarking, the men were incensed at the thoughtlessness of Congress

in affording them only the same ten dollars a month, less a three-dollar deduction

for clothing, that the government paid unskilled black laborers. When a paymaster

arrived, the men refused to accept the money. “It does certainly seem hard that they

should not get full pay when they were promised it by the men that enlisted them,”

Verplanck remarked in a letter to his mother,

and for a drafted man it is certainly harder yet. The men are all hard up enough

for money but they consider it a matter of pride and are willing to let the money

go. One of our men said that if he was not to be put on an equality with white

troops he was willing to serve the government for nothing. . . . I am sorry that

they will not take the seven dollars as they will be without a good many little

comforts which they would otherwise have, but at the same time I must say that

I admire their spirit.

54

In December, the 6th USCI took part in a raid, this one overland, forty miles

from Yorktown to a Confederate cavalry camp at Charles City Court House, halfway

to Richmond. The regiment, guarding ambulances and rations, stopped some miles

short of the objective while the white cavalry pushed on through “a severe storm of

wind and rain” and routed the enemy, capturing ninety men and fty-ve horses,

53

Compiled Military Service Record (CMSR), Christian A. Fleetwood, NA Microlm Pub

M1820, CMSRs of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served in the U.S. Colored Troops, roll 36; C.

A. Fleetwood Diary, 5 Oct 1863 (“weather”), 19 Oct 1863 (“Singing”), 27 Oct (“N.C.S.”), C. A.

Fleetwood Papers, Library of Congress; Longacre, Regiment of Slaves, pp. 13–14.

54

R. N. Verplanck to Dear Jenny, 24 Oct 1863, and to Dear Mother, 26 Nov 1863, both in R. N.

Verplanck Letters typescript, Poughkeepsie [N.Y.] Public Library.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

325

reported Brig. Gen. Isaac J. Wistar, commanding at Yorktown. The attackers suffered

ve wounded, whom they brought back to the place where the 6th USCI guarded

the wagons. Again, Wistar wrote that the “colored infantry did what was required of

them, . . . very severe duty (weather and roads considered). . . . Their position . . . , in

readiness to receive and guard prisoners and horses, issue rations, attend to wounded,

and do picket duty, on the return of the other exhausted troops, was found [to be] of

extreme advantage.” The gradual introduction to active service that the 4th and 6th

USCIs received was more effective and cost fewer casualties than the abrupt and

catastrophic immersion suffered earlier that year by other new black regiments in the

ghts at Fort Wagner and Milliken’s Bend.

55

The next operation undertaken by black soldiers stationed on the peninsula

grew out of General Butler’s other responsibility, besides commanding the de-

partment: acting as special agent for the exchange of prisoners of war. The agree-

ment for paroling and exchanging prisoners that had operated during the rst two

years of the war entailed release of prisoners within weeks, or at least months,

of capture, with the understanding that they would not return to the ghting until

formal exchange for prisoners of equal rank held by the other side. This under-

standing broke down when the Confederate government refused to acknowledge

the legitimacy of the Union’s black soldiers and announced its intention to pun-

ish them under state laws that governed slave rebellions and their white ofcers

under laws that punished inciting rebellions. In each case, the penalty was death.

55

OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 1, pp. 974–77 (“a severe,” p. 975; “colored infantry,” p. 976).

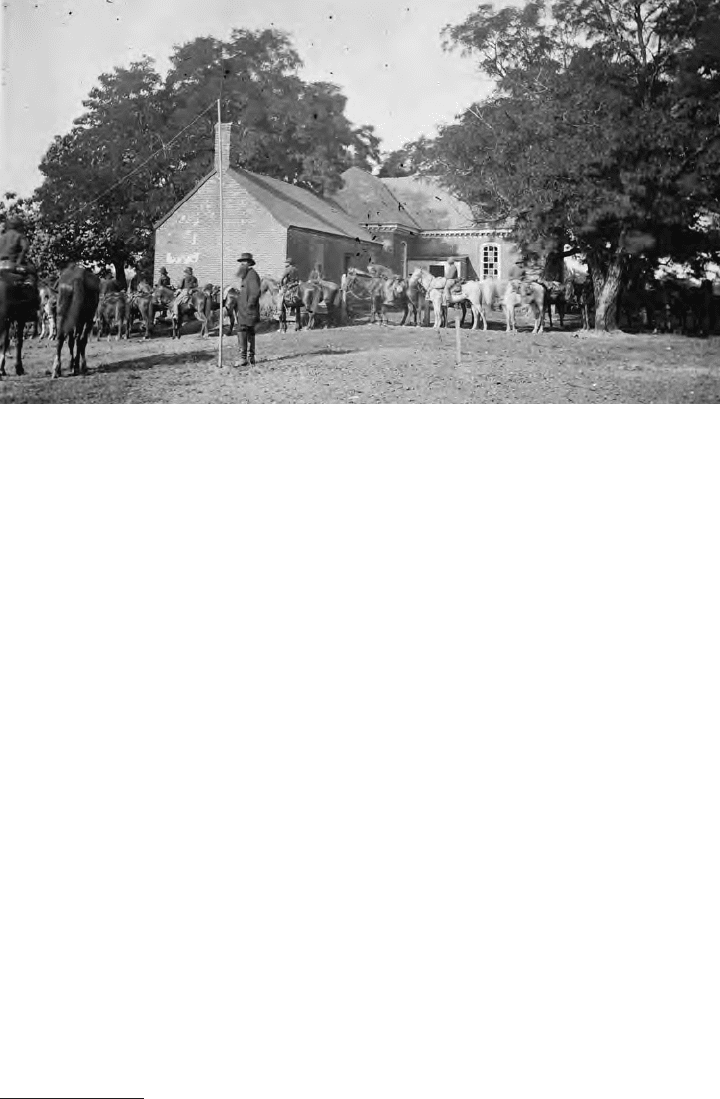

Charles City Court House, on the road between Williamsburg and Richmond, in the

spring of 1864

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

326

Even when men and ofcers of the U.S. Colored Troops reached Confederate

prisons, their captors refused to release them on the same terms that governed

other soldiers. “This is the point on which the whole matter hinges,” Stanton

explained to Butler. “Exchanging man for man and ofcer for ofcer, with the

exception the rebels make, is a substantial abandonment of the colored troops

and their ofcers to their fate, and would be a shameful dishonor to the Govern-

ment bound to protect them.”

56

Butler’s Department of Virginia and North Carolina included the Union pris-

oner of war camp at Point Lookout, Maryland. In the fall of 1863, it housed

more than 8,700 captive Confederates. A few days’ march up the peninsula from

Fort Monroe, the Confederacy’s capital held more than 11,000 Union prison-

ers. About 6,300 of them lived on Belle Isle, an island in the James River a few

hundred yards upstream from the city’s waterfront. Tobacco warehouses held

5,350 others, including 1,044 ofcers in the notorious Libby Prison. On the day

Butler took command at Fort Monroe, both sides agreed to release all medical

ofcers they held prisoner. Until that spring, chaplains and medical ofcers had

been exempt from imprisonment; but when Confederate authorities insisted on

holding a federal surgeon for trial on criminal charges, the system froze, with

hostage-taking on both sides quickly followed by retention of all captive medical

personnel. When the rst Union surgeons to be released arrived in Washington

at the end of November, they reported that the number of deaths in all the Rich-

mond prisons averaged fty a day, or fteen hundred a month. Inmates, they

said, ate meat only every fourth day. The more usual daily ration was one pound

of cornbread and a sweet potato.

57

Northerners received this news with horror. “The only prospect now of relief

to our prisoners is by our authorities acceding to the rebel terms for exchange,”

thus excluding black soldiers from the agreement, a New York Times editorial-

ist wrote, “or by Gen. Meade’s pushing on his victorious columns. If we do not

speedily operate in one of these ways, Death must in a few brief months relieve

the last of the . . . Union prisoners.” Butler heard of the possibility of a raid on the

Richmond prisons just days after he arrived at Fort Monroe. Almost simultane-

ously with the surgeons’ release, General Wistar, commanding at Yorktown, sent

Butler a proposal for a raid to free the prisoners, but two months passed before

circumstances favored such a move.

58

When the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia went into winter quarters,

General Robert E. Lee turned his attention to the reduced Union garrisons in

North Carolina. On 20 January 1864, he ordered Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett

to move against New Berne with ve infantry brigades drawn from Lee’s army

and the garrison at Petersburg, Virginia. This shift of about nine thousand men

56

OR, ser. 2, 6: 528 (quotation), 711–12; Charles W. Sanders Jr., In the Hands of the Enemy:

Military Prisons of the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005), pp. 146–

47, 151–52.

57

OR, ser. 2, 6: 501, 544, 566–75, 742; New York Times, 28 November 1863; New York Tribune,

1 December 1863. See OR, ser. 2, 6: 26–27, 35–36, 88–89, 109–10, 208–09, 381–82, 473–74, for an

outline of the breakdown of the system for exchanging medical ofcers.

58

OR, ser. 1, vol. 51, pt. 1, pp. 1282–84; New York Times, 28 November 1863 (quotation); Butler

Correspondence, 3: 143–44.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

327

to North Carolina would leave a force of barely thirty-ve hundred to defend the

Confederate capital. Five days after Pickett received Lee’s order and began gath-

ering his brigades, a Union secret agent in Richmond sent Butler word that the

Confederates intended to move the Union prisoners of war there to other sites.

The agent urged an attack on the city by a force of at least forty thousand federal

troops. Butler, with fewer than half that number scattered in ve garrisons be-

tween Norfolk and Yorktown, decided to act anyway. “Now, or never, is the time

to strike,” he told Stanton.

59

General Wistar’s sixty-ve hundred troops at Yorktown would carry out the

raid. Butler began to beg for cavalry reinforcements the day after he heard from

the agent in Richmond. While he waited for them, he sought to protect the secre-

cy of the operation by sending a coded message to an ofcer in Baltimore, asking

him to buy a map of Richmond. “My sending to buy one would cause remark,”

he explained. Secrecy was important to Butler, for the proposed expedition had

acquired more objectives since late November. Besides freeing the prisoners,

the raiders intended to torch “public buildings, arsenals, Tredegar Iron Works,

depots, railroad equipage, and commissary stores of the rebels,” and, if pos-

sible, capture Jefferson Davis and members of his cabinet. Wistar did not share

Butler’s hopes for secrecy. “It will be impossible to disguise the signicance of

the subject of your telegram any longer,” he wrote on 27 January when Butler

59

OR, ser. 1, 33: 482, 519–20 (“Now, or never,” p. 519), 1076, 1102–03. The estimate of the

strength of Pickett’s force is derived from statistics on pp. 1165, 1201, 1207, and 1247. Butler

Correspondence, 3: 228–29, 319, 331–32, 381–83, 564.

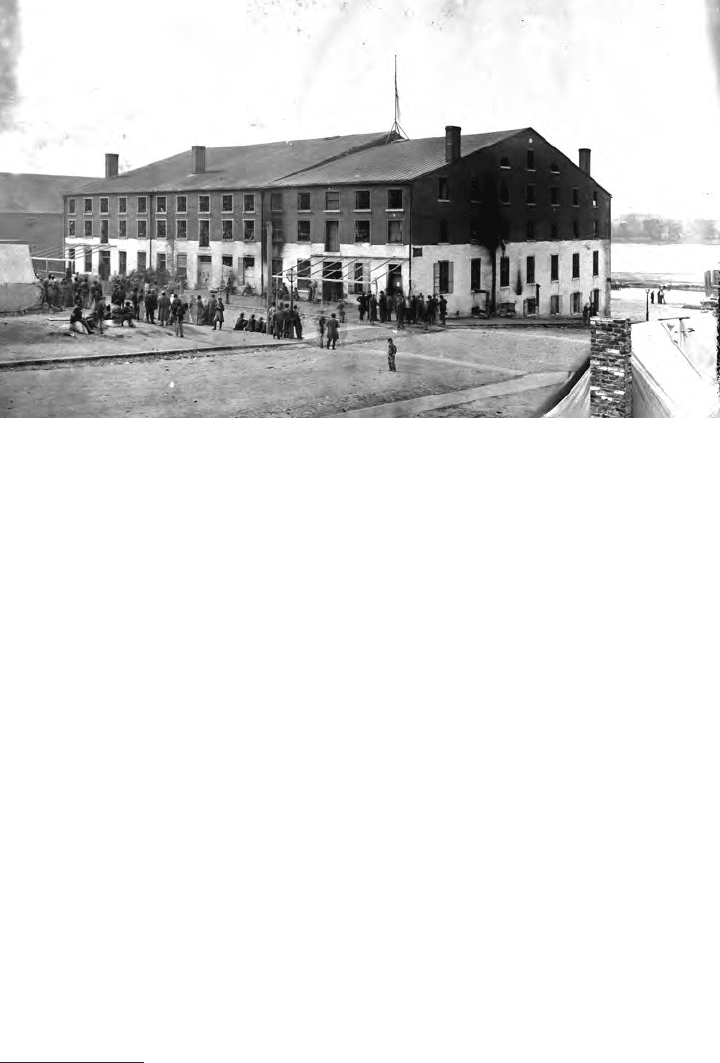

Libby Prison in Richmond housed captured Union ofcers.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

328

told him of the impending arrival of more cavalry. In the end, the reinforcement

amounted to only 281 men.

60

As the plan stood on the eve of its execution, Wistar would move against Rich-

mond with two brigades of infantry, about four thousand men, and one of cavalry,

about twenty-two hundred, accompanied by two light batteries. One of the infantry

brigades, commanded by Colonel Duncan, included the 4th, 5th, and 6th USCIs;

the other, three white regiments. Companies from ve cavalry regiments consti-

tuted the mounted brigade. The force was to move toward Richmond, the infantry

securing a bridge across the Chickahominy River while the cavalry dashed the last

twelve miles into the city. There, the raiders would divide into bands of between

two hundred fty and three hundred fty men. The rst of these was to attack the

Confederate navy yard on the James River; the second group was to empty Libby

Prison and, crossing the bridge to Belle Isle, free the prisoners there. This party

would also cut telegraph lines out of the city and destroy several rail bridges and

depots. The objective of the third party was Jefferson Davis’ residence, where it

was to arrest him. The fourth group, after cooperating with the second in freeing the

prisoners, was to destroy the Confederacy’s leading producer of heavy ordnance,

the Tredegar Iron Works. The rest of the cavalry would act as a reserve, waiting in

Capitol Square for the other groups to join it after they had done their work. They

were to complete the entire project within three hours, before Confederate troops

could arrive from their camp on the James River, about eight miles below the city.

61

The black regiments left their camp near Yorktown about 2:00 p.m. on Friday, 5

February, and reached Williamsburg, a twelve-mile march, after dark. The men car-

ried seventy rounds and six days’ rations. “Very tired and footsore from new shoes,”

Sergeant Major Fleetwood wrote. “Slept by a bush.” The next morning, an impromp-

tu tour of the 1862 battleeld by some of the ofcers delayed the expedition’s start.

“Fooling and zzling,” Fleetwood complained in his diary, but he used the time to

swap shoes with another soldier. The men were still in high spirits, as they had been

since the day before, when they learned of the raid they were to carry out. The bri-

gade moved forward late in the morning and did not stop at sunset. It was the night

before the new moon and “very dark,” Lieutenant Grabill told his ancée. “Once

when Colonel [James W.] Conine sent me forward with a message . . . I rode past

the whole brigade and was quite advanced in another brigade before I learned my

mistake. . . . I lay down a moment to wait for the column to get past some obstruction.

When I woke up I was alone in the silent darkness, and it was some time before I

caught up.” It was hours past midnight when the brigade nally ended its thirty-mile

march at New Kent Court House. “Completely broken down,” Fleetwood wrote.

62

While the infantry made camp, Wistar’s cavalry pressed on through the moon-

less night. At the Chickahominy, they found the planks of the bridge removed. Day-

light revealed a Confederate force waiting on the opposite shore and blocking nearby

60

OR, ser. 1, 33: 429, 448, 482; vol. 51, pt. 1, p. 1285 (“public buildings”). Butler Correspondence,

3: 340 (“It will be”), 351 (“My sending”), 360. Butler gave the strength of the cavalry reinforcement

as 380 in OR, ser. 1, 33: 439, but as 281 in two different messages in Butler Correspondence, 3:

345–46; the latter gure seems more likely.

61

OR, ser. 1, 33: 146, 521–22.

62

Ibid., pp. 146; NA M594, roll 206, 4th, 5th, and 6th USCIs; Fleetwood Diary, 5 (“Very tired”)

and 6 (“Fooling,” “Completely”) Feb 1864; E. F. Grabill to Friend Anna, 11 Feb 1864, Grabill Papers.

North Carolina and Virginia, 1861–1864

329

fords. With the element of surprise gone and the dash on Richmond forestalled, Wis-

tar thought that an attempt to force a crossing would be pointless and began a return

march. Duncan’s command was back at Yorktown by Tuesday, 9 February, “entirely

disgusted,” Fleetwood recorded. The brigade had marched well over one hundred

miles—one ofcer reckoned 125 miles—in less than ve days. Several ofcers found

the men’s endurance noteworthy. “We performed the hardest marching that I have

ever known a regiment to perform,” wrote Colonel Shurtleff, who had campaigned in

the mountains of West Virginia. “During the long march on Sat[urday] our regiment

did not lose a straggler, while the white brigade left ve hundred. Some of our boys

threw away knapsacks, clothing and all, but they would not fall out.”

63

Butler learned quickly that the Confederates had known about the plan for days.

A soldier in one of Wistar’s mounted regiments, imprisoned on a murder charge, had

escaped and ed to the nearest Confederate outpost, which passed him on to higher

authorities. By 4 February, Jefferson Davis felt secure enough in his preparations

for the raid to tell General Lee that he saw “no present necessity for your sending

troops here.” Even though the entire strength of the Richmond garrison was less than

that of Wistar’s force, all that was necessary to stop the expedition was to dismantle

the bridge over the Chickahominy and let the raiders know that they were expected.

More successful in freeing the prisoners was a tunnel dug by the inmates at Libby

Prison, by which 109 of them were able to escape on 9 February, the day Wistar’s

force returned to Yorktown. Fifty-nine eventually reached Union lines.

64

Late that month, Union troops mounted another raid on the Richmond prisons,

this one led by a division commander in the Army of the Potomac, Brig. Gen. Judson

Kilpatrick. By this time, Duncan’s brigade had acquired a fourth regiment, one that

Duncan and Col. John W. Ames of the 6th USCI had asked for. The 22d USCI was

organizing at Camp William Penn under the command of Col. Joseph B. Kiddoo,

former major of the 6th, “an ofcer of great merit and wide experience, and one

whom we would be proud to have . . . with us in the Brigade,” Ames and Duncan told

General Butler. Kiddoo himself was eager to come to Butler’s department, the two

colonels said; he felt “that in no other Dept . . . will the experiment of colored troops

be carried out on so grand a scale.” There was a large element of truth in this attery,

for at this point in the war Butler had thrown himself wholeheartedly into the U.S.

Colored Troops project. General Wistar approved the colonels’ request, and the 22d

USCI reached Yorktown on 13 February.

65

The new regiment took up the routine of guard duty and fatigues at once,

before the men had time to build adequate quarters. “Have lost ve men here,”

Assistant Surgeon Charles G. G. Merrill told his father. “It has been very cold &

Grabill’s letter attests to the men’s morale, as does a letter signed “Hard Cracker” that appeared in

the Anglo-African, 20 February 1864, quoted in Noah A. Trudeau, Like Men of War: Black Troops

in the Civil War, 1862–1865 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1998), p. 203. “Hard Cracker” wrote that the

column reached New Kent Court House at 1:30 a.m.; Fleetwood, at 2:30; Grabill, at 3:30.

63

OR, ser. 1, 33: 145–48; NA M594, roll 206, 6th USCI; Fleetwood Diary, 7 Feb 1864 (“entirely

disgusted”); G. W. Shurtleff to My dear little girl, 11 Feb 1864 (“We performed”), G. W. Shurtleff

Papers, OC.

64

OR, ser. 1, 33: 144, 1076, 1148, 1157–58; vol. 51, pt. 2, p. 818 (“no present”). Frank E. Moran,

“Colonel Rose’s Tunnel at Libby Prison,” Century Magazine 35 (1888): 770–90.

65

OR, ser. 1, 33: 170–74; Col S. A. Duncan et al. to Maj Gen B. F. Butler, 3 Feb 1864, 22d USCI,

Entry 57C, RG 94, NA; NA M594, roll 208, 22d USCI; William G. Robertson, “From the Crater to

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

330

rainy, . . . & the men on guard had to stay out all night in the pelting storms—then

they would be taken sick, come to the hospital, lie down on the ground, (before we

had our bunks built) and die from pure debility & exhaustion.” On 26 February, the

22d USCI moved from Yorktown twelve miles up the peninsula to Williamsburg.

66

Kilpatrick’s force, more than thirty-ve hundred horsemen, was to enter Rich-

mond from the north, free the prisoners, and head east for the Union garrison at

Williamsburg. When Butler heard of the raid, he sent a mixed force of infantry

and cavalry forward to New Kent Court House, a small crossroads settlement of

the type that was common in Virginia counties, “to aid in case of disaster, to re-

ceive prisoners, or to cover retreat,” as he told General Halleck on 29 February.

Duncan’s brigade began its march the next afternoon. About dark, rain began to

fall and continued, mixed with snow, through the night. “Slipping, stumbling, fall-

ing,” Fleetwood recorded in his diary. “Nothing but mud and slush.” At midnight,

when the column halted for a few hours’ rest, “the men with nothing but a blanket

bivouacked on the cold damp ground,” Surgeon James O. Moore of the 22d USCI

wrote. They moved on at 3:30, stopping about dawn for a breakfast of coffee and

hardtack. By the time they made camp west of the courthouse that afternoon, they

had covered more than forty miles in less than twenty-four hours.

67

The march took them through country where the white residents seemed ter-

ried of black soldiers. As the column splashed through Williamsburg, 2d Lt. Jo-

seph J. Scroggs of the 5th USCI saw no one in the streets. “Afraid of the ‘nigger’ I

suppose,” he noted in his diary. “I went up to a house,” Assistant Surgeon Merrill

wrote home, “& got a good breakfast of corn bread and milk. They were glad to

be protected. The way cows, pigs & hens suffered was a caution.” Surgeon Moore

agreed with his assistant about the troops’ foraging but added that freeing “about

twenty” slaves who joined the column was more important than supplementing the

troops’ rations or punishing disloyal Virginians.

68

On the morning of 3 March, six miles west of New Kent Court House, Butler’s

force met Kilpatrick’s raiders, who had turned away from Richmond without en-

tering the city. About ve hundred men from the city’s Confederate garrison and

some 750 cavalry and artillery from the Army of Northern Virginia had managed

to inict 340 casualties on the Union force—nearly 10 percent of its total strength.

All that remained for Duncan’s brigade to do was to cover the horsemen’s retreat.

“Gen. Wistar has found out that these men can march well & carry anything that is

put on them,” Lieutenant Verplanck wrote, “so he keeps us following after cavalry

New Market Heights: A Tale of Two Divisions,” in Black Soldiers in Blue, ed. Smith, pp. 169–99,

esp. pp. 169–71, 194–95.

66

NA M594, roll 208, 22d USCI; C. G. G. Merrill to Dear Father, 28 Feb 1864, C. G. G. Merrill

Papers typescript, Sterling Library, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

67

OR, ser. 1, 33: 183, 193, 198, 615, 618 (“to aid”); Fleetwood Diary, 1 Mar 1864; J. O. Moore

to My Dearest Lizzie, 5 Mar 1864, J. O. Moore Papers, DU. Estimates of the distance marched vary

from forty-two to forty-ve miles. OR, ser. 1, 33: 198; NA M594, roll 208, 4th, 5th, and 6th USCIs;

J. O. Scroggs Diary typescript, 2 Mar 1864, MHI; R. N. Verplanck to Dear Mother, 13 Mar 1864,

Verplanck Letters.

68

C. G. G. Merrill to My dear Father, 5 Mar 1864, Merrill Papers; Moore to My Dearest Lizzie,

5 Mar 1864; Scroggs Diary, 1 (quotation), 2, and 3 Mar 1864.