Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Virginia, May–October 1864

341

sixty miles long and would have stretched “from the Rapidan [River] to Rich-

mond.” This never happened, of course. Grant’s movement plan called for an

advance toward different fords of the Rapidan several miles apart. Besides, it

was necessary to keep many wagons in reserve in order to deliver a constant

ow of supplies to the army while wagons returning to base brought back men

wounded in the ghting. One train that carried wounded from Spotsylvania

Court House to Belle Plain, a landing on the Potomac River, included 256

ambulances and 164 wagons and was four miles long. Guarding these trains,

the task assigned to Ferrero’s 4th Division, was no triing chore. During the

course of the campaign, federal commanders reported that Confederate horse-

men were active everywhere from Belle Plain to Fort Monroe.

9

Two days of travel took Ferrero’s command as far as the Rapidan River.

Once across, the division passed through the Chancellorsville battleeld of

1863. Col. Delavan Bates of the 30th USCI saw “the ground . . . covered with

bones of last year’s dead.” Also present were the corpses of more than three

thousand soldiers, Union and Confederate, who had died during the previous

three days. On 9 May, Captain Rogall recorded, “weather cloudy, gloomy,

dusty, smell of dead bodies decaying from the last ght.” For eleven days after

Ferrero’s division crossed the Rapidan, the sound of gunre accompanied its

march; not until 17 May did Rogall mention hearing songbirds in the woods.

That day, the 30th USCI camped near where Bates had been taken prisoner

during the Union debacle at Chancellorsville exactly fty-four weeks earlier,

while he was serving as a lieutenant in the 121st New York. That he had re-

turned to his regiment from captivity within three weeks, well in time to take

part in the battle of Gettysburg at the beginning of July 1863, showed how

smoothly prisoner exchange worked during the middle part of the war, before

the Confederate government mounted obstructions in response to federal en-

listment of black soldiers.

10

The gunre that Captain Rogall recorded in his diary for eleven consecutive days

was the sound of Grant’s successive attempts to bring Lee’s army to battle in the

open, where greater federal numbers could decide the result. Lee’s response, after the

ghting near Wilderness Tavern on 5 May, was to ght from behind hastily prepared

fortications, forcing Grant to attack. Seventeen days’ ghting, rst in the Wilder-

ness, then around Spotsylvania Court House, cost the Army of the Potomac more

than thirty-seven thousand casualties—slightly more than 30 percent of its strength

at the beginning of the month. Grant spent the rest of May edging southeast in re-

curring attempts to get around the Confederates’ right ank, moving ever closer to

Richmond. As he did so, his base of supplies moved down the Potomac from land-

ing to landing, with wagons rolling “over narrow roads, through a densely wooded

country,” as Grant described it, “with a lack of wharves at each new base from which

9

OR, ser. 1, 33: 828 (“as far as”); vol. 36, pt. 1, pp. 230, 277, and pt. 2, pp. 779, 828, 856. Ulysses

S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, 2 vols. (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1886), 2: 188

(“from the Rapidan”). Six horses or mules were usually sufcient to draw an army wagon. Reports

do not state whether the ambulances required teams of two, four, or six animals.

10

OR, ser. 1, vol. 36, pt. 1, pp. 133, 987–91; NA M594, roll 208, 30th USCI; D. Bates to Father,

15 May (quotation) and 26 May 1863, both in D. Bates Letters, Historians Files, U.S. Army Center

of Military History; Rogall Diary, 9 (quotation), 12, and 17 May 1864.

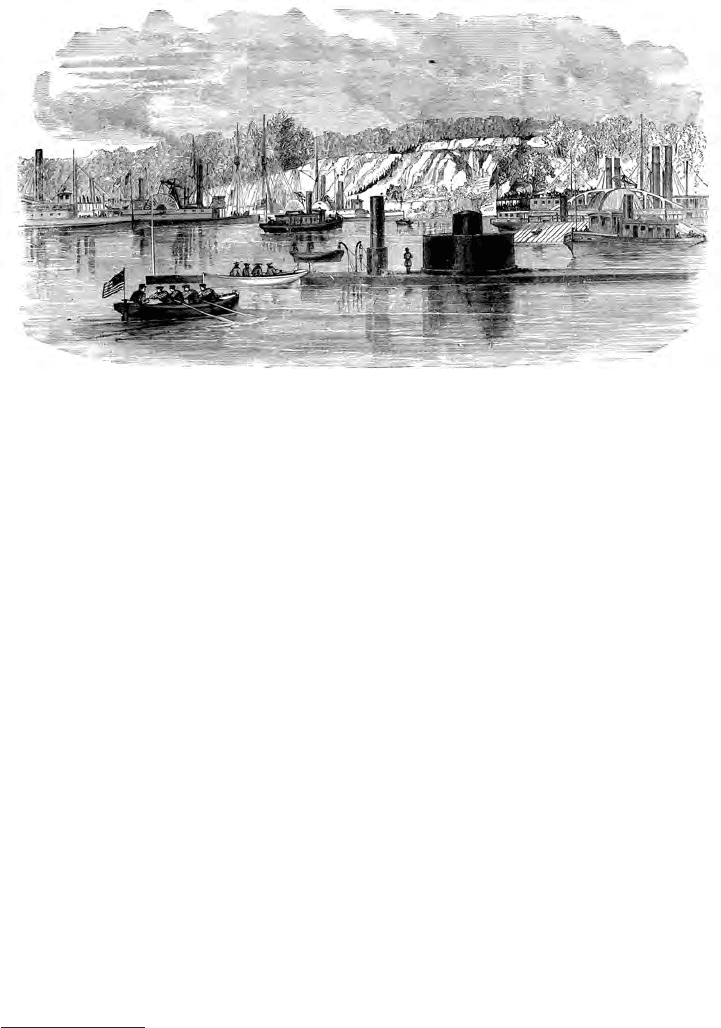

In the spring of 1864, the Union advance on Richmond gave slaves like these in Hanover

County, just north of the city, a chance at freedom.

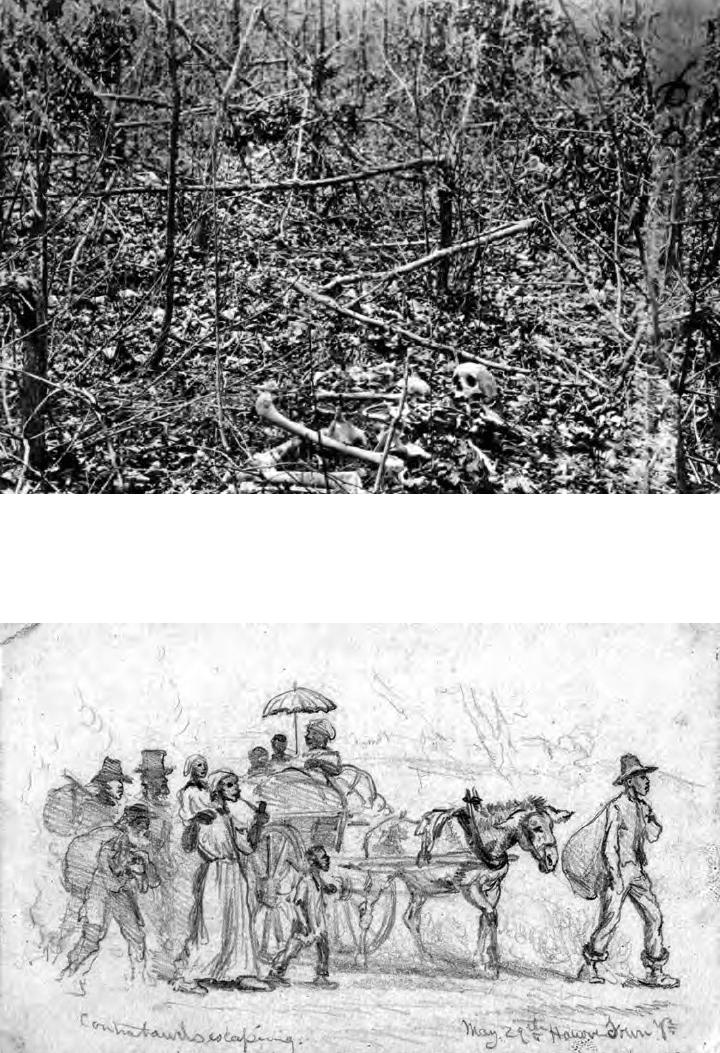

The 1864 battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House took place on much of

the same ground that the opposing armies had fought over just one year before. Marching

through the woods, Union troops encountered many grisly relics of the earlier ghting.

Virginia, May–October 1864

343

to conveniently discharge vessels.” During the month, by Grant’s account, Ferrero’s

division had “but little difculty” protecting the trains. Ferrero’s reports claimed two

attacks by “superior forces,” both of which his troops repelled, but Rogall dismissed

both incidents as the work of guerrillas. Two men of the 23d USCI suffered wounds.

“The colored troops stand everything well that we have had to go through yet,” Colo-

nel Bates wrote. “How they will ght remains to be seen.”

11

The spring campaign was barely two weeks old on 19 May, when the Army

of the Potomac nally penetrated beyond the site of its 1863 defeat. On that day,

the rst escaped slaves began to reach federal lines. The Union advance of 1864

did not lead to the release of hundreds of slaves at a time, as sometimes happened

elsewhere in the South. The Tidewater and Piedmont counties of Virginia lacked the

large plantations that characterized the cotton, rice, and sugar regions of the Confed-

eracy. North of the Rapidan, moreover, the country had been the scene of continual

ghting during the previous two years, and the bolder and more ingenious slaves had

already found ways to ee bondage. In addition, many slaveholders had taken steps

to remove their human property from the path of the federal army. Nevertheless, the

turmoil created by the spring offensive offered the remaining black civilians another

chance. Singly and in groups they made their way to the Union soldiers, often bring-

ing intelligence of Confederate movements and troop strength that the liberating in-

vaders found useful. Their numbers increased as the army reached the North Anna

River, about twenty-ve miles from Richmond. “Contraband[s] . . . ocking around

us,” Captain Rogall remarked at the end of the month.

12

On 4 May, the day the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan, General But-

ler’s troops at Fort Monroe boarded transports for the voyage toward Richmond.

“Start your forces on the night of the 4th,” Grant had prompted Butler just six days

earlier, “so as to be as far up the James River as you can get by daylight the morning

of the 5th, and push from that time with all your might for the accomplishment of the

object before you.” Despite Grant’s urging, the embarkation went slowly, especially

that of the troops recently arrived from South Carolina, who did not nish load-

ing until nearly midnight. While the newcomers struggled aboard, Hinks’ division

waited. “Embarked the Division and hauled into the Stream,” Sergeant Major Fleet-

wood noted in his diary. “Lay there all night.” In broad daylight the next morning, the

eet’s departure resembled a regatta more than a landing force. “Crowd on all steam,

and hurry up,” Butler ordered Hinks, as his own boat, the Greyhound, chugged in and

out among the other vessels. Upstream, Confederates on shore counted more than

seventy-ve gunboats and transports in the otilla. The transports carried about thirty

thousand soldiers. Hinks’ division formed the vanguard, dropping off the 1st and 22d

USCIs with four twelve-pounders of Battery B, 2d USCA, to seize Wilson’s Wharf

11

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1036, 1045; vol. 36, pt. 1, pp. 23 (“over narrow”), 986 (“superior forces”),

1070–71. Rogall Diary, 15 and 19 May 1864; D. Bates to Father, 15 May 1864, Bates Letters.

12

OR, ser. 1, vol. 36, pt. 2, pp. 541, 918–19, and pt. 3, pp. 51, 84, 100, 121, 148; Rogall Diary,

29 May 1864; Ira Berlin et al., eds., The Destruction of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University

Press, 1985), pp. 59, 69–70, and The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 86, 110; Lynda J. Morgan, Emancipation in Virginia’s

Tobacco Belt, 1850–1870 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992), pp. 19–22, 111–12; Steven E.

Tripp, Yankee Town, Southern City: Race and Class Relations in Civil War Lynchburg (New York:

New York University Press, 1997), pp. 144–45.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

344

on the north bank, several miles beyond the mouth of the Chickahominy River. Far-

ther along, the 10th and the recently arrived 37th USCIs with four guns of Battery

M, 3d New York Light Artillery, landed at Fort Powhatan on the opposite shore. The

three remaining regiments of Col. Samuel A. Duncan’s brigade and two guns of

each battery disembarked at City Point, on the south bank of the James, just below

the mouth of the Appomattox River and about seven miles from Petersburg, the rail

junction that connected Virginia with the states south of it.

13

Having split Hinks’ division into three parts, Butler landed the rest of the

expedition, some thirty thousand white troops organized in ve divisions, on

a peninsula called Bermuda Hundred just across the Appomattox from City

Point. Not until the day after the landing did he push one of those brigades west

toward the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad. Four more brigades followed

the next day. By that time, the Confederates had been able to add twenty-six

hundred men to the garrisons of the two cities. Five days after the Union land-

ing, reinforcements that arrived by rail from North Carolina doubled the de-

fenders’ numbers to more than fourteen thousand.

14

Here began the collapse of the campaign. Rather than move at once up the

James toward Richmond against a Confederate garrison that numbered barely

seven thousand at rst, Butler entertained the idea of moving on Petersburg.

13

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1009 (“Start your”), 1053; vol. 36, pt. 2, pp. 165, 398, 432 (“Crowd on”), 956;

NA M594, roll 205, 2d U.S. Colored Artillery; Fleetwood Diary, 4 May 1864. Robertson, Back Door

to Richmond, pp. 57–60, conveys a vivid sense of the festive air on the morning of 5 May.

14

Union strength from OR, ser. 1, 33: 1053–56, and Robertson, Back Door to Richmond, p.

59. Confederate returns from the Department of Richmond, 20 Apr 1864, show 7,265 ofcers and

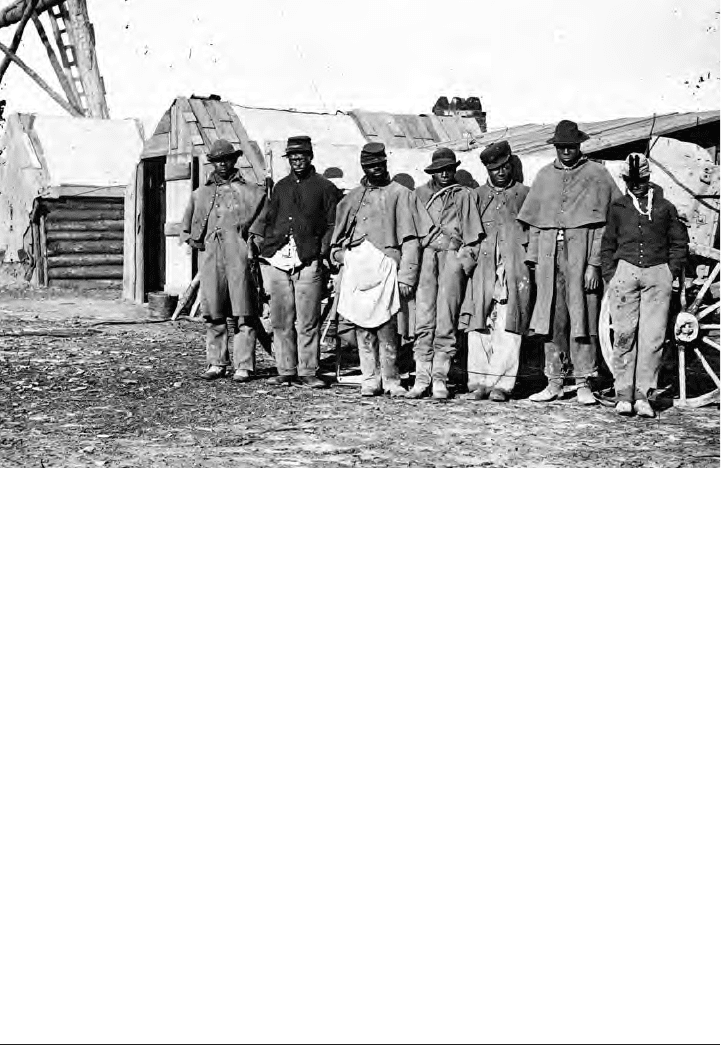

This view of General Butler’s progress up the James River on 5 May 1864 captures

the bustling scene as two Union ironclads guard side-wheel transports and tugs and

rowboats ply back and forth between the otilla and Fort Powhatan, on the bluff above

the water.

Virginia, May–October 1864

345

Dispatches from Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck in Washington led him to believe

that Grant had defeated Lee’s army, which, he understood, was withdrawing

toward Richmond. Inclined to wait for Grant’s approach but unable to decide

in the meantime whether to move on Petersburg or Richmond, Butler quarreled

with his two corps commanders, Smith and Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore,

who led the X Corps, made up of the recent arrivals from South Carolina. By

the time the three generals managed to move four divisions toward Richmond,

enough Confederates were present to stop them on 16 May at Drewry’s Bluff,

a height on the James River about eight miles north of the Union trenches at

Bermuda Hundred. Butler’s rst venture at active operations had collapsed in

less than two weeks.

15

While the major portion of the campaign agged, the men of Hinks’ division be-

gan to entrench the places where they went ashore and to take part in what one com-

pany commander called “scouts and skirmishes too numerous to mention.” These

began the day after their arrival, when a detachment of Company B, 1st USCI, seized

one of the Confederate signal stations that had reported the eet’s progress upriver,

and continued with the capture of others later in the week. On 9 May, Colonel Dun-

can led the 4th and 6th USCIs on a reconnaissance from City Point about halfway to

Petersburg. “Lay still all of the cool of the day,” Sergeant Major Fleetwood recorded.

“Started in the heat. . . . Countermarched and tried another road. [T]urned back[.]

Arrived at City Point 11 eve.” Three days later, Hinks took the same regiments and

his four pieces of artillery to occupy Spring Hill, a site four miles up the Appomattox

River. During the rst two weeks of the occupation of City Point, the troops endured

several attacks of a sort that one company commander dismissed with: “Rebs visited

our pickets [with] no loss to us.” Fire from gunboats in the river helped to disperse

the attackers. Despite the troops’ constant activity, disappointment hung in the air. “I

am afraid there has been a ne opportunity . . . lost here by inexcusable tardiness,”

Lieutenant Scroggs wrote on 10 May. “We lay here four days without advancing a

step and then on making a feeble attempt yesterday we found them prepared for us.

Very courteous in us not to take them unawares.”

16

As soon as black residents along the James River saw that the newcomers in-

tended to stay, they began escaping to the Union positions. Many were too old or

too young to work, but those who were able found employment quickly with the

expedition’s quartermaster or as servants. They brought with them the kind of lo-

cal knowledge that federal armies found invaluable throughout the South. “I have

men present for duty. OR, ser. 1, 33: 1299; Mark Grimsley, And Keep Moving On: The Virginia

Campaign, May–June 1864 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), pp. 120–25.

15

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1299; Grimsley, And Keep Moving On, pp. 126–28; Edward G. Longacre, Army

of Amateurs: General Benjamin F. Butler and the Army of the James, 1863–1865 (Mechanicsburg,

Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1997), pp. 87–100; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The

Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 722–24; Robertson, Back Door to

Richmond, pp. 250–52.

16

OR, ser. 1, vol. 36, pt. 2, pp. 22–24, 31, 165–66. NA M594, roll 205, 1st USCI; roll 206, 5th

USCI (“scouts and skirmishes”), 6th USCI (“Rebs visited”). Fleetwood Diary, 9 May 1864; Scroggs

Diary, 10 May 1864. For other criticism of Butler, see E. F. Grabill to My Darling Beloved, 28 May

1864, E. F. Grabill Papers, OC; G. W. Shurtleff to Dearest Mary, 12 May 1864, Shurtleff Papers;

R. N. Verplanck to Dear Mother, 20 May 1864, R. N. Verplanck Letters typescript, Poughkeepsie

[N.Y.] Public Library; Robertson, Back Door to Richmond, p. 251.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

346

got a rst rate fellow who left Petersburg [three days ago] & who knows every road

& by path from here [to] there,” 2d Lt. Robert N. Verplanck told his mother. Other

slaves waited for Union troops to come to them. Assistant Surgeon James O. Moore

accompanied a lieutenant and twenty enlisted men of the 22d USCI on a foraging

expedition. “We halted at a house,” he wrote, “or rather I should have said that a slave

came in [and] wanted us to . . . get his Father Mother & six bros and sisters” from the

farm of former President John Tyler. “We took all the slaves & ordered them to take a

reasonable amount of clothing bedding &c whereupon they walked very deliberately

into the best room took the best bed best pillows. . . . I never saw a happier lot [of]

human beings than were those slaves when they were on their way to freedom.”

17

At least once, escaped slaves had the chance to accuse one of their former

masters of mistreatment and to punish him for it. On 10 May, a planter named

William H. Clopton, whose estate had been home to twenty-ve slaves, came to

Wilson’s Wharf to take the oath of allegiance. “He gave a attering account of his

former treatment of his slaves,” Surgeon Moore wrote. “In fact he considered him-

self [more] a public benefactor than otherwise.” When some of his former slaves

who had taken refuge in the Union camp accused him of whipping them for their

reluctance to work on Confederate fortications, Brig. Gen. Edward A. Wild had

Clopton seized and tied. Sgt. George W. Hatton of the 1st USCI described the

scene for readers of the Christian Recorder, the weekly newspaper of the African

Methodist Episcopal Church:

William Harris, a soldier in our regiment . . . , who was acquainted with the gentle-

man, and who used to belong to him, was called upon to undress him. . . . Mr.

Harris played his part conspicuously, bringing the blood from his loins at every

stroke, and not forgetting to remind the gentleman of the days gone by. After giv-

ing him some fteen or twenty well-directed strokes, the ladies, one after another,

came up and gave him a like number, to remind him that they were no longer his.

Reporting the incident to General Hinks, Wild told him, “I wish it to be distinctly

understood . . . that I shall do the same thing again under similar circumstances.”

Hinks’ response was to convene a general court-martial and prefer charges against

Wild, for he would not “countenance . . . any Conduct on the part of my command

not in accordance with the principles recognized for . . . modern warfare between

Civilized Nations.” Although the court convicted Wild, General Butler set the ver-

dict aside, for Hinks had failed to follow a department order directing that a major-

ity of U.S. Colored Troops ofcers sit on courts trying cases that involved black

soldiers or their ofcers.

18

Two weeks after Clopton’s ogging, the garrison at Wilson’s Wharf had to

hold the post against an assault. On the afternoon of 24 May, Confederates ap-

peared in the wood nearby, “evidently,” Wild reported, “with the design of rushing

17

R. N. Verplanck to Dear Mother, 12 May and 2 Jun (“I have got”) 1864, Verplanck Letters; J. O.

Moore to My Dearest Lizzie, 12 May 1864, J. O. Moore Papers, Duke University (DU), Durham, N.C.

18

Moore to My Dearest Lizzie, 12 May 1864. Hinks and Wild quoted in Berlin et al., Destruction

of Slavery, pp. 96–97; Hatton quoted in Edwin S. Redkey, ed., A Grand Army of Black Men: Letters

from African-American Soldiers in the Union Army, 1861–1865 (New York: Cambridge University

Press, 1992), pp. 95–96. Butler’s General Order 46, 5 Dec 1863, is in OR, ser. 3, 3: 1139–44; the

Virginia, May–October 1864

347

in upon us suddenly.” An unknown number of attackers—perhaps as many as three

thousand—red on the Union trenches, the steamboat landing, and a nearby signal

station for ninety minutes before their commander, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, sent a

ag of truce to the defenders with a demand for their surrender. If they submitted,

he said, he would treat them as prisoners of war; if they did not, he could not guar-

antee that any of them would survive the nal assault. Wild, commanding eleven

hundred ofcers and men of the 1st and 10th USCIs, refused the offer and ring

resumed, joined in by a Union gunboat in the river. The only Confederate attempt

to storm the Union position left about two dozen bodies so close to the trenches

that the attackers had to leave them behind when they withdrew during the night.

As to other Confederate casualties, Wild could only guess. His own amounted to

twenty-two ofcers and men killed, wounded, and missing.

19

A month after Hinks took command, Lieutenant Verplanck wrote that the gen-

eral “is becoming more & more attached to his division and has the greatest con-

dence in their ghting qualities. Indeed they have already shown themselves here

in several little affairs.” One of these affairs, Verplanck went on, occurred near City

Point on 18 May, when pickets of the 4th and 6th USCI, although outnumbered by

clause governing the composition of courts-martial for U.S. Colored Troops enlisted men and

ofcers is on p. 1144.

19

OR, ser. 1, vol. 36, pt. 2, pp. 269–72 (quotation, p. 270). NA M594, roll 205, 1st USCI; roll

206, 10th USCI.

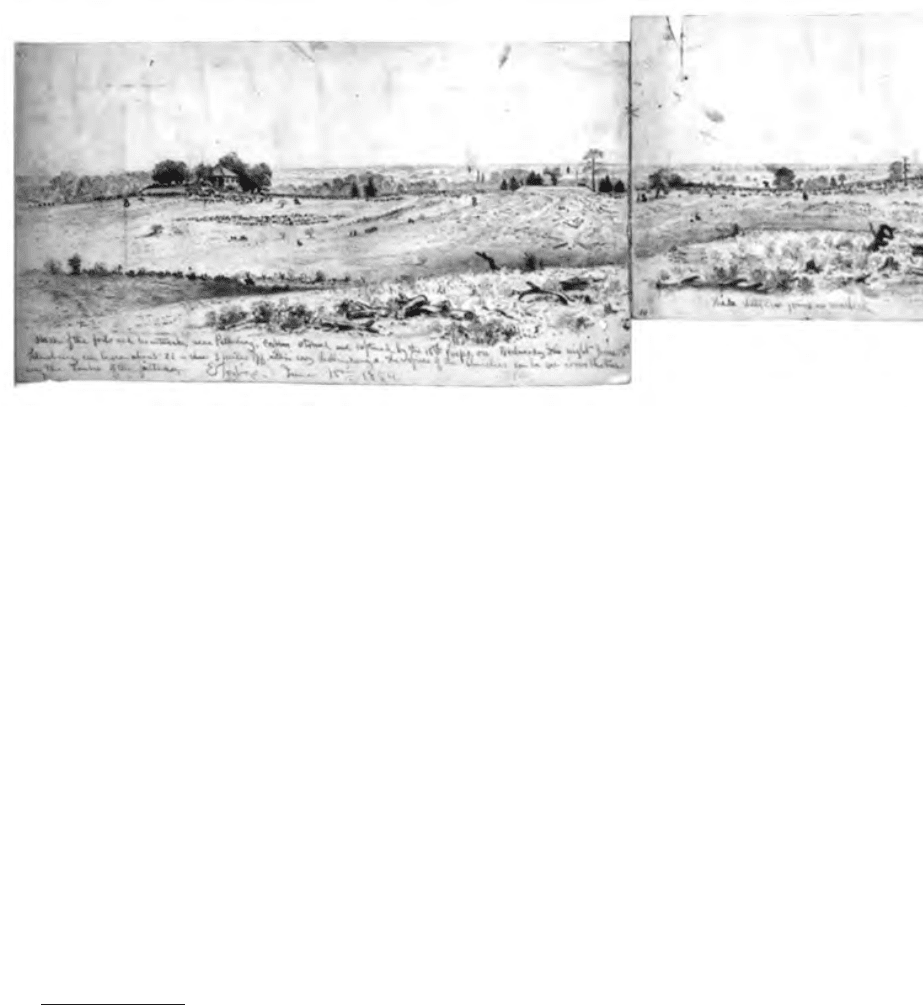

Many escaped slaves preferred to work as laborers rather than enlist as soldiers.

Employment with Union troops at Bermuda Hundred made it easy for these civilians to

come by greatcoats and other items of military uniform.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

348

Confederate troops, “soon put them to y, but not however without the loss of two

killed & ve wounded, but the rebels were awfully used up. These fellows ght

awfully in earnest and will have to [be] restrained from treating the rebels as they

were treated at Fort Pillow.”

20

The stalemate in front of Petersburg continued, punctuated by small ghts.

“Our regiment and the Fourth Colored made a sortie . . . to drive back some rebs

who were approaching a little too close for good manners,” 1st Lt. Elliott F. Grabill

of the 5th USCI wrote on 1 June. “The movement was executed most splendidly.

I never saw soldiers maneuver better than those two regiments did yesterday in

the face of the enemy.” While Grabill wrote, he could hear cannon re from the

Army of the Potomac, north of the James River. As Meade’s force drew nearer to

Richmond, General Smith led the two white divisions of the XVIII Corps across

the river to assist them. General Hinks and the Colored Division stayed behind at

City Point, Spring Hill, Fort Powhatan, and Wilson’s Wharf.

21

During the second week of the month, General Gillmore commanded the re-

mainder of the Army of the James in an unsuccessful operation against Petersburg

that caused recriminations between him and Butler. Hinks, who had been continually

shufing his regiments between their four bases as the occasion demanded, had some

thirteen hundred men of the 1st and 6th USCIs on hand to contribute to Gillmore’s at-

tack. The two regiments moved forward during the night. As daylight came on 9 June,

both Hinks and the brigadier who was to command the main body of troops viewed

the Confederate works and judged them too strong for a successful assault. Gillmore

agreed and withdrew the troops. When Butler received a report of the operation, he

called it “unfortunate and ill-conducted,” and relieved Gillmore of command.

22

Meanwhile, Grant’s Overland Campaign had ground to a halt northeast of

Richmond, with the loss of more than ve thousand men at Cold Harbor on the

morning of 3 June. The commanding general returned General Smith and his two

divisions of the XVIII Corps to Butler. As their leading regiments embarked once

more for Bermuda Hundred on 13 June, another attack on Petersburg was in the

works. Unable to break the Army of Northern Virginia by a frontal attack, Grant

intended to capture the rail center and cut off his enemy’s source of supplies. To

accomplish this, he would bring the Army of the Potomac south of the James River

to join Butler’s Army of the James.

23

Smith did not learn that he was to lead the attack until Butler told him, just as

he and his troops reached Bermuda Hundred. The II Corps would follow Smith

across the James by boat to take part in the operation while the rest of the army

waited on the north bank for its engineers to complete a 1,240-foot pontoon bridge.

The rst of Smith’s divisions arrived on the south bank late in the morning of 14

June. The second landed at 8:00 p.m., half an hour after sunset. Hinks, whose divi-

sion of Smith’s corps had never left its posts along the river, received his orders

20

NA M594, roll 206, 4th and 6th USCIs; Verplanck to Dear Mother, 20 May 1864.

21

E. F. Grabill to My Own Precious One, 1 Jun 1864, Grabill Papers; Robertson, Back Door to

Richmond, pp. 240–41.

22

OR, ser. 1, vol. 36, pt. 2, pp. 275 (“unfortunate”), 295, 306–08; NA M594, roll 205, 1st USCI,

and roll 206, 6th USCI.

23

OR, ser. 1, 33: 1053–55; vol. 36, pt. 1, p. 180; vol. 40, pt. 2, pp. 3, 17, 20. Brooks D. Simpson,

Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity, 1822–1865 (Boston: Houghton Mifin, 2000), pp. 335–37.

Virginia, May–October 1864

349

some time on 14 June, the day before the attack. He and his men were to take part

in the assault and capture the Confederate works northeast of Petersburg. Three

regiments of dismounted cavalry—the 1st and 2d USCCs and the 5th Massachu-

setts (Colored)—would augment the division’s two brigades, although some of the

regiments were absent at other posts along the river. With one battery—six guns—

of artillery for each brigade, the troops present numbered 3,747 ofcers and men.

They would act in concert with General Smith’s divisions, which were en route

to join them. “I do not want Petersburg visited, however,” Grant warned Butler,

“unless it is held, nor an attempt to take it unless you feel a reasonable degree of

condence of success. I think troops should take nothing with them except what

they carry, depending upon supplies being sent after the place is secured.”

24

Any written instructions that Butler may have given Smith seem to have dis-

appeared from the ofcial record. Hinks’ orders from Butler were merely to meet

Smith at a landing on the south bank of the Appomattox River “at 2 a.m. precisely.”

He would receive further orders then. None of the surviving reports of Smith, the

corps commander; of his divisional generals, Hinks and two others; or of six bri-

gade commanders, convey any idea of the purpose of the attack. All agree that

the troops awoke well before dawn, began moving south from the river, and then

turned west toward the Confederate defensive line around Petersburg.

25

Hinks met Smith and learned that his division was to follow the cavalry forward.

The men of the division were up an hour or two before dawn and waited under arms

until after sunrise for the twenty-ve hundred troopers to pass them. Hinks was con-

dent, even cocky: if Butler would return all the detachments of his division, he had

written a few days earlier, “I will place Petersburg or my position [as divisional com-

mander] at your disposal.” When the cavalry came under re from a Confederate bat-

tery about 7:00 a.m., the dismounted skirmishers and horse holders continued to move

south, leaving a few men to keep an eye on the battery until Hinks’ infantry arrived.

26

The battery—observers disagreed as to the number of guns—red from six

hundred yards away, beyond woods full of fallen trees, vines, and brush. Hinks

formed two lines: Colonel Duncan’s brigade took the lead with the 5th USCI on the

right and the 22d, 4th, and 6th USCIs to the left. Behind them came the 1st USCI

with half of the dismounted 5th Massachusetts Cavalry on its left. The dismounted

troopers caused some delay because the cavalry’s dismounted drill had no com-

mands for forming an infantry line of battle. Many of the troopers, besides, had

been in the army for less than three months. At last, the lines plunged into what

Colonel Duncan called “the blindness of the wood.”

27

First to emerge were three companies of the 4th USCI. The men set off with

a yell for the enemy position. While their ofcers tried to restore order and Con-

federate artillerymen adjusted their guns to cover this new menace, the 5th Mas-

sachusetts Cavalry in the rear began ring into the troops just ahead of them—the

24

OR, ser. 1, vol. 36, pt. 1, pp. 25–26, and pt. 3, p. 755 (quotation); vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 236–37, 298,

720–21. Longacre, Army of Amateurs, pp. 141–45.

25

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 705, 714–15, 717, 719–26, 728–30 (quotation, p. 720); vol. 51, pt.

1, pp. 265–69, 1252–65. Grimsley, And Keep Moving On, pp. 227–28.

26

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, p. 721; vol. 51, pt. 1, pp. 263, 265. Butler Correspondence, 4: 361 (quotation).

27

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, p. 721 (Hinks counted a total of six guns in two positions), 725

(Kautz, three guns); vol. 51, pt. 1, pp. 265 (Duncan, four guns), 266 (quotation).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

350

4th USCI and those companies of the 6th that were not lost in the woods. “Cut up

badly. Regt broke and retreated,” Sergeant Major Fleetwood wrote in his diary.

Before the left of the Union line could recover itself, Col. Joseph B. Kiddoo on

the right seized the opportunity to lead the 22d USCI forward, followed by the 5th

USCI, while the enemy gunners’ attention was elsewhere. While these two regi-

ments crossed the three or four hundred yards between the edge of the woods and

the Confederate position, the gunners nally noticed their approach and rode off

with all but one of their twelve-pounders. Men of the 22d turned the remaining gun

around and sent a few shots after them.

28

By the time the entire division assembled, the hour was 9:00 a.m. Caught at

the edge of the woods between the Confederate artillery in front and the 5th Mas-

sachusetts Cavalry in rear, the 4th USCI had lost one hundred twenty ofcers and

men killed and wounded. The column moved on. Hinks put the 5th USCI in the

lead as skirmishers, the men advancing in pairs to cover each other, one always

having his rie loaded. An hour’s march brought them in sight of the enemy again.

In front lay the eastern end of Petersburg’s defenses, a ring of fty-ve artillery po-

sitions. Those directly in front of the skirmishers appeared as Batteries 7 through

11 on Union maps. Fire from their guns kept Hinks’ two batteries from taking a

position from which they could shell the Confederate line. About 1:00 p.m., Hinks

relieved the 5th USCIs from the advance and moved the 4th, 22d, and 1st USCIs

forward ve hundred yards across a eld to where a low crest offered partial pro-

tection from enemy re. There they lay for ve hours. “The situation was anything

28

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 721 (Hinks estimated the distance as 400 yards), 724; vol. 51, pt. 1,

pp. 265 (Duncan, 300 yards), 266. Fleetwood Diary, 15 Jun 1864; James M. Paradis, Strike the Blow

for Freedom: The 6th United States Colored Infantry in the Civil War (Shippensburg, Pa.: White

Mane Press, 1998), pp. 52–53. Sgt. Maj. C. A. Fleetwood, of the 4th USCI, which received the re of

the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, agreed with Col. S. A. Duncan that the dismounted cavalrymen red

into the troops ahead of them. Anglo-African, 9 July 1864. So did Chaplain H. M. Turner, of the 1st

USCI, which was in line next to the cavalrymen. Anglo-African, 23 July 1864.