Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Virginia, May–October 1864

351

but a pleasant one to remain in,” Sgt. Maj. John Arno of the 1st USCI wrote for

readers of the Anglo-African, “with the scorching sun on the backs of the troops

and the cannons belching forth their murderous missiles.”

29

At 7:00, half an hour before sundown, the entire XVIII Corps line, black soldiers

and white, advanced. By General Smith’s calculation, Hinks’ division captured Bat-

teries 7 and 8 in about twenty minutes. “They shouted ‘Fort Pillow,’ and the rebs

were shown no mercy,” Pvt. Charles T. Beman of the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry told

his father. Night fell, but a three-quarter moon and muzzle ashes of the Confeder-

ate guns guided them to the next bastions by way of a 600-yard ravine choked with

tree stumps, fallen timber, and water. Afterward, there were disputes about which

regiment captured which position, but everyone was pleased with the day’s results,

including General Smith, who had been a notorious doubter of the Colored Troops’

abilities. Lieutenant Verplanck sent his mother a diagram of the ght: “You can see

that they enladed us and fronted us & generally ripped us but it didn’t stop us,” he

wrote. “I have come through all right but I have smelt powder sure.”

30

Smith suspended operations at about 9:00 p.m. because of darkness. Even

while his troops assaulted the ring of artillery positions outside Petersburg, the

rst Confederate reinforcements were arriving in the city by rail. By midmorning

the next day, General Lee himself was at Drewry’s Bluff, only fteen miles north

of Petersburg, with the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia close behind. Just

arrived on the south bank of the James, Grant began to move the four corps of the

Army of the Potomac toward the city, but the moment had passed when its capture

by a single bold stroke had been possible. The attack might not have failed if Grant

29

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 721–22; vol. 51, pt. 1, pp. 266–67. Anglo-African, 9 July 1864;

Paradis, Strike the Blow for Freedom, pp. 54–55.

30

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 705–06, 722; vol. 51, pt. 1, p. 267–68. Beman quoted in Redkey,

Grand Army of Black Men, p. 99. R. N. Verplanck to Dear Mother, 17 Jun 1864, Verplanck Letters.

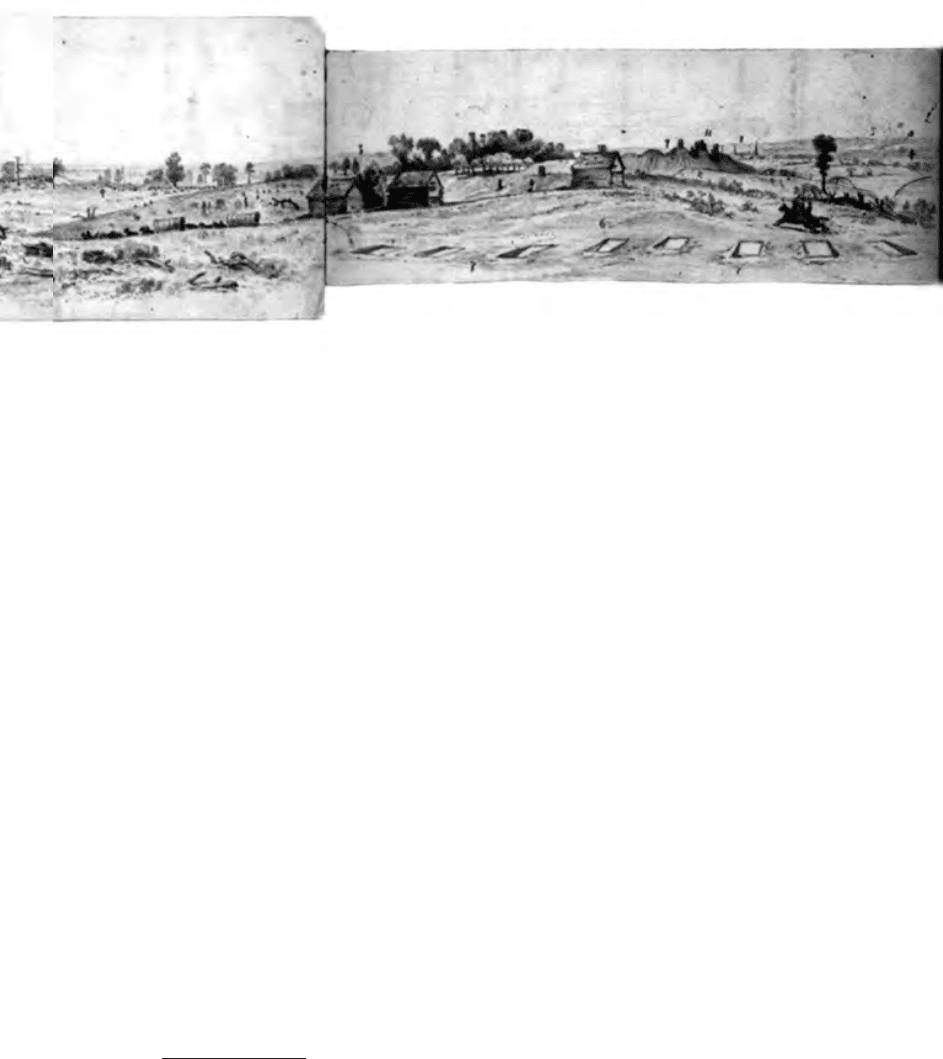

This panoramic view by the artist Edwin Forbes shows the ground across which the XVIII

Corps attacked on 15 June 1865. The Confederate line ran along the widely spaced trees

in the middle distance.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

352

had given the orders directly to Smith, a career soldier, rather than transmitting

them through Butler, a lawyer and politician who had never directed a successful

military operation.

31

Fighting went on for three more days, but Hinks’ division did not play an ac-

tive role. Its casualties during that time amounted to less than 10 percent of those

it suffered in the morning and evening assaults on the rst day. In all, Hinks’ divi-

sion lost more than ve hundred ofcers and enlisted men killed, wounded, and

missing. “For the last sixty-four hours I have had but ten hours sleep,” Assistant

Surgeon Charles G. G. Merrill wrote. “Today I brought in twenty-two wagons full

of wounded and am going out tonight to bring in twelve wagons full more. We

had lots of operations yesterday.” The day after Hinks’ division left the line, Capt.

Solon A. Carter of the general’s staff told his wife how, during the battle,

Our Surgeon sat down to eat with us, just from the scene of his work (his operat-

ing table), with coat and vest off and his sleeves rolled up, his shirt and even his

pantaloons besmeared with the blood of the poor fellows he had been carving

up—We didn’t any of us mind it so much but wondered what the folks at home

would think of such an occurrence.

32

Private Beman’s remark that “the rebs were shown no mercy” was apparently

no idle boast. The day after the battle, a reporter for the New York Tribune described

a conversation he overheard: “‘Well,’ said Gen. Butler’s Chief of Staff to a tall ser-

geant, ‘you had a pretty tough ght there on the left.’ ‘Yes, Sir; and we lost a good

many good ofcers and men.’ ‘How many prisoners did you take, sergeant?’ ‘Not

any alive, sir,’ was the signicant response.” The reporter quoted General Smith

on the performance of Hinks’ division: “They don’t give my Provost Marshal [the

staff ofcer responsible for prisoners of war] the least trouble, and I don’t believe

they contribute toward lling any of the hospitals with Rebel wounded.” The an-

tislavery, Republican Tribune headed the dispatch: “The Assault on Petersburg—

Valor of the Colored Troops—They Take no Prisoners, and Leave no Wounded.”

Within a week, the story had spread throughout the army. Colonel Bates and the

30th USCI had marched with the Army of the Potomac to the James River from

the Rapidan. “The colored troops in Butler’s command took a line of very strong

works . . . , ghting splendidly,” he told his father. “They took no prisoners.”

33

Some of the black soldiers themselves talked, and even boasted, about what

they had done. “The colored troops took ve forts here on Tuesday,” wrote a white

soldier in the trenches at Petersburg. “I saw some of them to-day. They said the

white folks took some prisoners, but they did not.” Chaplain Henry M. Turner of

the 1st USCI, one of the few black chaplains, deplored the practice and told read-

31

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 705, 749, 801.

32

Ibid., vol. 51, pt. 1, p. 267. Civil War casualty gures vary widely. The total of 416 in Col.

S. A. Duncan’s report for 15–18 June 1864 (OR, ser. 1, vol. 51, pt. 1, p. 269), is greater than the 391

casualties for his brigade that appears in statistical tables covering the entire Union force around

Richmond and Petersburg for the period 15–30 Jun 1864 (vol. 40, pt. 1, p. 237). C. G. G. Merrill to

Dear Annie, 16 Jun 1864, C. G. G. Merrill Papers, Yale University (YU), New Haven, Conn.; S. A.

Carter to My own precious wife, 20 Jun 1864, S. A. Carter Papers, MHI.

33

New York Tribune, 21 June 1864; D. Bates to Father, 27 Jun 1864, Bates Letters.

Virginia, May–October 1864

353

ers of the Christian Recorder so. He de-

scribed the attack, with Colored Troops

and Confederates alike shouting “Fort

Pillow!” “This seems to be the battle-

cry on both sides,” Turner wrote. When

the attackers got inside the forts, a few

Confederates “held up their hands and

pleaded for mercy, but our boys thought

that over Jordan would be the best place

for them, and sent them there, with a

very few exceptions.” The chaplain

added that although “an immense num-

ber of both white and colored people”

endorsed the practice of killing prison-

ers, he opposed it strongly. “True, the

rebels have set the example, particularly

in killing the colored soldiers; but it is

a cruel one, and two cruel acts never

make one humane act. Such a course

of warfare is an outrage upon civiliza-

tion and Christianity.” In the end, ex-

perience as much as moral sentiment

gradually diminished the number of

massacres, region by region, as Confed-

erates learned that black soldiers would

impose the same terms on them, while

black soldiers became more willing to

take prisoners after their rst battle, realizing how quickly fortune could reverse

itself. But since the war extended from Virginia to Texas, and entire regiments were

going into battle for the rst time even during its last weeks, the cycle of atrocity

and vengeance stopped only when the ghting ended.

34

By the end of June, the two armies had settled into parallel systems of trenches that

skirted Petersburg and extended to the west. Union soldiers worked on the gun posi-

tions they had captured on the rst day so that their thirty-pounders bore on the city

and its railroad bridges. Confederate snipers encouraged men to keep their heads down,

rather than admire the stretch of the Appomattox River that lay beyond the besieged

city and the ripening grain in the elds. Other distractions from the view were “millions

of savage ies” and the stench of the unburied corpses that their larvae fed on.

35

In any case, the trenches required continual maintenance. “We have worked

hard day & night most of the time, which has near worn us out,” Captain Rickard

of the 19th USCI wrote, “but after a few days of sleep we will be all right again.”

34

E. C. Mather to Dear Brother, 19 Jun 1864, E. C. Mather Papers, Dartmouth College, Hanover,

N.H.; Christian Recorder, 9 July 1864. Prisoner-killing was not uncommon in Europe during both

World Wars. Malcolm Brown, The Imperial War Museum Book of the Western Front (London:

Pan Books, 2001), pp. 176–81; Gerald F. Linderman, The World Within War: America’s Combat

Experience in World War II (New York: Free Press, 1997), pp. 118–26.

35

Rogall Diary, 13 Jul 1864.

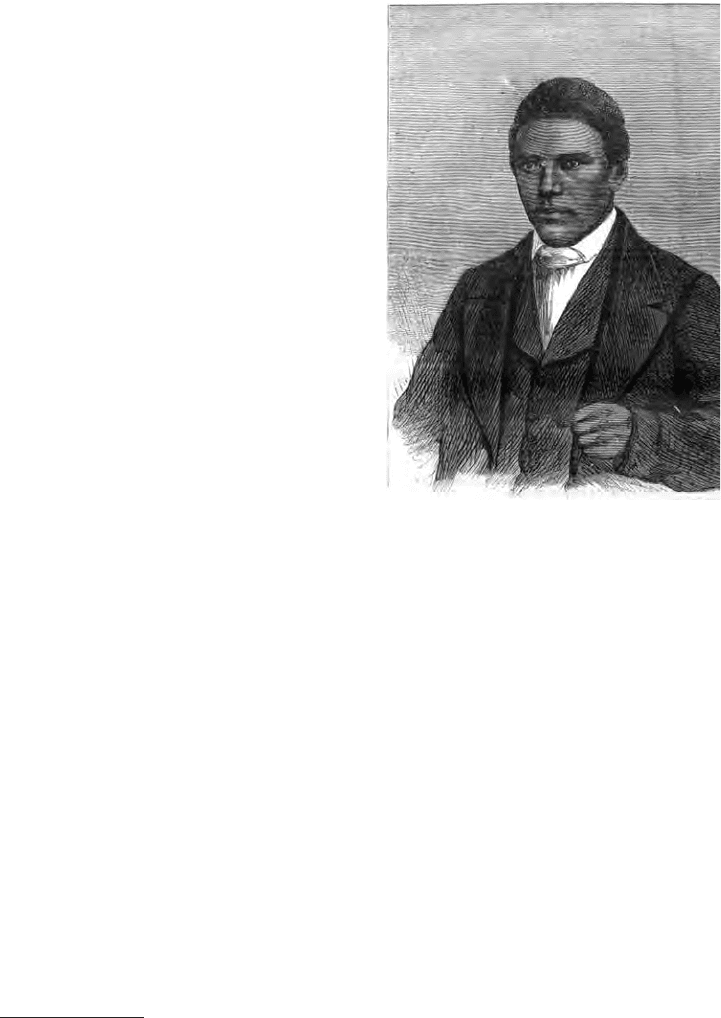

A future bishop of the African Methodist

Episcopal Church, Henry M. Turner,

was appointed chaplain of the 1st U.S.

Colored Infantry in 1863.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

354

When they were not shoring up the trenches, the men dug wells, for no appre-

ciable rain fell between early June, before the beginning of the siege, and 19

July. Sergeant Major Fleetwood’s diary recorded that he “washed and changed

[clothes]” on 20 June, 7 July, and 29 July. With water and clean clothing in such

short supply, it was no wonder that the Prussian-born Captain Rogall complained

of “lices.” Men inevitably grew bored and took chances, so that one diarist wrote

that the “usual amount of sharpshooting” afforded “an occasional casualty to re-

lieve the monotony.” Captain Carter of Hinks’ divisional staff found that the men

became inured to cannon re, “and it is really surprising how little attention any

one pays to an artillery ght alone.” Mortars were a different matter. Men liked

to watch rounds red by their own side. “The bomb presents a ne appearance

in the night,” Assistant Surgeon Merrill told his sister, “going up half a mile in

the air—a red line of re—then gradually falling & exploding after it reaches

the ground.” Men held the mortars in awe, and a round from the enemy would

have troops diving for their “gopher holes.” The reason for the name, Lieutenant

Scroggs explained, was that “when a shell comes over, ofcers and men without

distinction or ‘standing upon the order,’ incontinently ‘go for’ them.” Lieutenant

Verplanck took a day from his staff duties to visit his regiment, the 6th USCI, and

found his old comrades “quite comfortable in their pits & holes. Everybody was

as close to the ground as they could get.”

36

Since the rst week of May, ofcers and enlisted men of the U.S. Colored

Troops in the Army of the James had scanned the newspapers for items about

Ferrero’s division of the IX Corps, which had been guarding the wagons during

Grant’s overland march. Soldiers in Butler’s army, some of them veterans of ten

months’ campaigning in North Carolina and Virginia, were anxious lest their un-

seasoned comrades bring discredit on black troops everywhere. “The Colored Di-

vision in Burnside’s Corps has not yet taken active part in a single engagement,”

Lieutenant Grabill observed in June.

37

Not only were Ferrero’s men untested in battle; three months of continual ac-

tivity—rst during the march from the Rapidan to the James, then in the trenches

around Petersburg—had left them no time to master the basic elements of soldier-

ing. The 39th USCI had received ries only when passing through Washington,

D.C., in April. “Target practice, except for the ve days at Manassas Junction, has

been out of the question,” the commanding ofcer wrote, “and this for men who

have never been allowed the handling . . . of re arms, has proved to be to[o] short

to enable many to determine . . . whether the explosive part of the cartridge is the

powder or the ball, many believing that because it is the ball that kills [it] should

be put into the gun rst. A few put in two or more loads at a time.” Others merely

red from the shoulder without aiming. Many, like some rural white recruits, did

36

S. A. Carter to My own darling Em, 3 Jul 1864, Carter Papers; Fleetwood Diary, 20 Jun

(quotation), 7 and 29 Jul 1864; E. F. Grabill to My Own Little Puss, 24 Jun 1864, Grabill Papers; C.

G. G. Merrill to Dear Annie, 4 Jul 1864, Merrill Papers; J. H. Rickard to Dear Brother, 21 Jul 1864,

Rickard Papers; Rogall Diary, 25 Jun and 4 Jul 1864 (“lices”); Scroggs Diary, 7 (“an occasional”),

19, 20 (“when a shell”), and 26 (“usual amount”) Jul 1864; R. N. Verplanck to Dear Mother, 26

Jun and 27 Jul 1864 (quotation), both in Verplanck Letters; Robert K. Krick, Civil War Weather in

Virginia (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007), pp. 130–33.

37

E. F. Grabill to My Own Darling, 9 June 1864, Grabill Papers.

Virginia, May–October 1864

355

not know their left feet from their right. To these former slaves from Maryland,

“every one is Captain or Boss and no amount of correction has so far rectied their

knowledge of rank,” the ofcer complained. Still, he thought, “I fully believe the

material for good soldiers exists in the regiment, but that it takes longer to develop

it, there can be no question.”

38

The lack of experience among General Ferrero’s soldiers was evident, and

noted by their own ofcers. The 30th USCI had “lost but few men yet,” Colonel

Bates wrote at the end of June. “Have been in no regular battle, but have been

under sharp picket re, shelling, &c. . . . The men do well so far.” Grant, who

had embraced the U.S. Colored Troops project a year earlier, displayed more

condence in his black soldiers and their commander. In mid-July, he wrote to

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that Ferrero “deserves great credit . . . for

the manner in which he protected our immense wagon train with a division of

undisciplined colored troops. . . . He did his work of guarding the trains and

disciplined his troops at the same time, so that they came through to the James

River better prepared to go into battle than if they had been in a quiet school of

instruction during the same time.”

39

Ferrero’s division spent the rst three weeks of July away from the IX Corps,

serving in turn with each of the other corps in the Army of the Potomac. The siege

of Petersburg required exibility of all the troops engaged in it that summer, for

a Confederate raid into Maryland and Pennsylvania compelled Grant to withdraw

one corps to defend Washington, leaving operations around Richmond and Peters-

burg to the remaining six, including the cavalry corps, that constituted Meade’s

Army of the Potomac and Butler’s Army of the James. Fatigues formed a large part

of the duties that fell to Ferrero’s men, for Meade believed that the U.S. Colored

Troops made better laborers than they did soldiers. Even so, he could promise one

of the corps commanders to whom he lent Ferrero’s division only that the black

troops would “partially relieve your labor details.” White troops continued to dig

their own trenches along the Union line around Petersburg throughout the siege,

and black soldiers manned advanced picket posts to keep an eye on the enemy

as often as they dug or carried. By the time Ferrero’s division returned to the IX

Corps, on 22 July, General Burnside was nurturing a bold scheme to break the

Confederate line: perhaps, even, to end the war. He intended to use black troops as

the spearhead of this effort.

40

The idea originated with an infantry regiment from the anthracite region of

Pennsylvania. Some of the miners in its ranks proposed tunneling under the Con-

federate defenses and detonating a charge powerful enough to destroy a section of

38

Maj Quincy McNeil to Brig Gen J. A. Rawlings, 13 Aug 1864, 39th USCI, Entry 57C,

Regimental Papers, RG 94, NA.

39

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 3, p. 252 (“deserves great”); Bates to Father, 27 Jun 1864.

40

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, p. 595, and pt. 3, pp. 144, 304, 476–77. Meade’s views on black

soldiers are on pp. 187, 192; black soldiers on picket duty, pp. 166, 182, 234; fatigue details from

Ferrero’s division, pp. 236, 304–05; fatigue details from white divisions, pp. 231–33, 236–37, 262–62.

For a division of white troops furnishing 250 to 700 men daily for road repair and construction of

fortications, see 2d Div, X Corps, Special Order 7, 6 Jun 1864, Entry 5195, 2d Div, X Corps, Special

Orders, pt. 2, Polyonymous Successions of Cmds, RG 393, Rcds of U.S. Army Continental Cmds, NA.

For a black regiment keeping 100 to 300 of its men in the front line around the clock, see Brig Gen P. A.

Devin to Col F. B. Pond, 1 Jun 1864, Entry 5178, 2d Div, X Corps, Letters Sent (LS), pt. 2, RG 393, NA.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

356

the enemy trench and enable Union

troops to capture Petersburg. Their

colonel took the plan to Burnside,

who liked it and defended it against

all doubters, chief among them

Meade, while the Pennsylvanians

dug. Beginning on 25 June, they

took twenty-ve days to complete

a tunnel more than ve hundred

ten feet long from a ravine behind

the Union trenches to a point un-

der the Confederate line, which lay

about one hundred fty yards from

the federal position. In the next few

days, they nished a lateral passage

seventy-ve feet long across the

head of the longer tunnel, making

an underground T-shape with the

head of the T roughly following the

line of the Confederate trench above

it. Along the lateral were eight small

rooms, or magazines, each intended

to hold between twelve hundred and

fourteen hundred pounds of pow-

der—some six tons in all. Meade

had the entire charge reduced to

four tons, or three hundred twenty

kegs, citing the advice of his engi-

neering ofcer, who was unenthusi-

astic about the project. On 26 July, Burnside asked for eight thousand sandbags to

close the magazines and the lateral passage so that the full force of the blast would

travel upward to the Confederate trench.

41

On the same day, Burnside outlined for Meade the infantry advance that would

come immediately after the explosion. His plan called for Ferrero’s division to lead

the attack, with both of its brigades advancing in column. The two columns would

skirt the crater caused by the explosion, with the lead regiment of each stopping to

secure the ruins of the Confederate trenches on either side of the crater while the

regiments behind them moved on to seize a crest of ground that Union observers

believed to be weakly held, some ve hundred yards beyond the severely damaged

Confederate front line. On the other side of this rise lay the city and its railroads.

If Ferrero’s division could gain the crest, Burnside thought, it could continue to

41

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 46, 59–60, 131, 136–37, and pt. 3, p. 354. The Pennsylvanians’

commanding ofcer stated the dimensions in congressional testimony. Report of the Joint Committee

on the Conduct of the War, 9 vols. (Wilmington, N.C.: Broadfoot Publishing, 1998 [1863–1865]),

2: 15–17, 113.

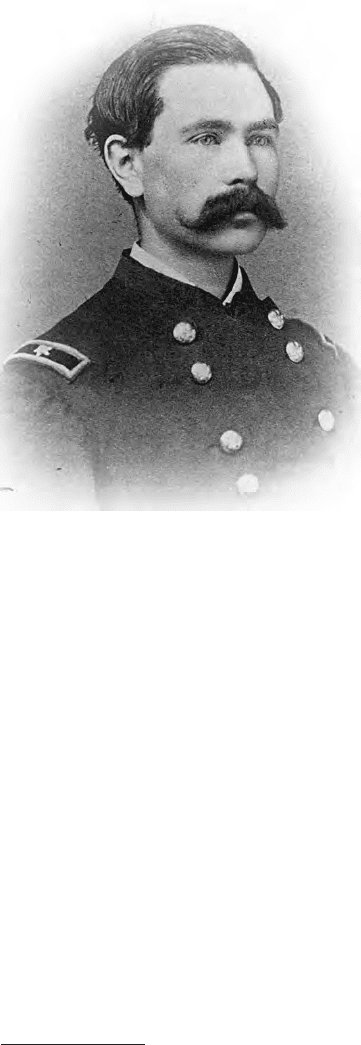

Delavan Bates had just turned twenty-four

years old when he was appointed colonel

of the 30th U.S. Colored Infantry in March

1864.

Virginia, May–October 1864

357

move downhill and “right into the town.” The honor of capturing Petersburg would

belong to black soldiers.

42

Meade demurred. Just two weeks earlier, he had told his other corps com-

manders that he was reluctant to use Ferrero’s men even for routine picket duty

in front of the Union lines. That he would assent to the black division’s leading a

major assault was unimaginable. Having already told Grant his doubts about the

entire mine project, he proposed to Burnside that they submit the question of the

black troops’ role in the attack to the commander of all the Union armies.

43

Meade presented the matter as a political question, Grant told congressional

investigators that December. “General Meade said that if we put the colored troops

in front . . . and it should prove a failure, it would then be said, and very properly,

that we were shoving those people ahead to get killed because we did not care

anything about them. But that could not be said if we put white troops in front.”

A presidential election lay less than four months ahead. Grant, whose wife’s fam-

ily owned slaves, had adhered without a murmur to the Lincoln administration’s

policies of emancipation and black enlistment in the spring of 1863. Such loyalty,

besides his victories at Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga, helped to ce-

ment his good relations with the president. Grant saw Meade’s point at once, and

on the afternoon of 29 July, some twelve hours before the explosion and attack,

Burnside received a message from Meade’s chief of staff: “the lieutenant general

commanding the armies . . . directs that [the attacking] columns be formed of the

white troops.”

44

Burnside had three divisions of white infantry with which to carry out this order.

The two closest to the site of the mine, led by Brig. Gen. Robert B. Potter and Brig.

Gen. Orlando D. Willcox, were worn out from weeks of digging trenches under enemy

re. Somewhat better rested, Burnside thought, was Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie’s divi-

sion, although it would have to undertake an overnight march in order to reach the next

day’s battleeld. “So I said, ‘It will be fair to cast lots,’” Burnside recalled the scene.

“And so they did cast lots, and General Ledlie drew the advance. He at once left my

headquarters, in a very cheerful mood. . . . [N]o time could be lost in making the neces-

sary arrangements, as it was then certainly 3 o’clock in the afternoon and the assault

was to be made next morning.”

45

Within a few hours of Meade’s conversation with Grant, Ferrero learned

that the white divisions of the IX Corps, and not his own men, would lead the

attack. Burnside had certainly revealed his own plans for the black division

some time before 17 July, when Ferrero mentioned “the proposed assault” in

a letter. A few weeks after the event, Burnside told a court of inquiry that he

had “instructed [Ferrero] to drill his troops” in preparation for the attack. Sur-

vivors of the assault continued for the rest of their lives to debate the question

of the division’s readiness. Ferrero’s report, dated two days after the assault,

mentioned no special training. Captain Rogall wrote in his diary about the 27th

42

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 126, 136 (quotation).

43

Ibid., pp. 60, 130–31, and pt. 3, pp. 187, 192.

44

Ibid., pt. 1, p. 137 (“the lieutenant”); Report of the Joint Committee, 2: 18, 111 (“General

Meade”). Brooks D. Simpson, Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and

Reconstruction, 1861–1868 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), pp. 3–5, 36–46.

45

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, p. 61.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

358

USCI’s “digging rie pits, dangerous position,” on 26 July, four days before

the projected attack. The same day, Sgt. William McCoslin sent a letter to the

Christian Recorder, saying that the 29th USCI had “built two forts and about

three miles of breastworks, which shows . . . that we are learning to make

fortications, whether we learn to ght or not. We are now lying in camp, . . .

resting a day or two. . . . We have worked in that way for eight or ten days with-

out stopping.” The drill that Burnside urged Ferrero to institute was probably

barely enough to teach men who had seen only a few months’ service to move

from column into line “by the right companies, on the right into line wheel, the

left companies on the right into line, and . . . the leading regiment of the left

brigade to execute the reverse movement to the left,” a sequence of movements

to secure the wrecked enemy trenches on either side of the crater that would

have bewildered untrained men. In any case, a shortage of ofcers hampered

training of any kind. “The regiment by sickness and details is very short of of-

cers for duty,” the commanding ofcer of the 19th USCI complained just a

week before the assault. “The labor upon the remaining ofcers . . . is so great,

that it is almost impossible in so new a regiment, that they would do justice to

themselves or their commands.” The men of Ferrero’s division might have been

ill prepared to lead the assault, even if Meade’s qualms had not sidelined them,

but the other divisions of Burnside’s corps had little more experience than Fer-

rero’s, either on the drill eld or in battle.

46

The IX Corps was unique in the Army of the Potomac. It had its beginnings in

the summer of 1862 and was composed of federal regiments withdrawn from the

Carolinas to strengthen Union forces in Virginia after McClellan’s failure to take

Richmond that spring. This was the rst instance of the Army’s stripping other

departments to reinforce operations closer to Washington, a practice that persisted

for the next two years.

By the summer of 1864, only twelve of the forty-one white regiments in the

corps had served with it since arriving from the Carolinas. Eight of the others

had joined in time for the Virginia and Maryland campaigns during the summer

and fall of 1862 and the IX Corps’ expeditions to Mississippi and Tennessee in

1863. Of the remaining twenty-one regiments, seventeen dated from the sum-

mer of 1863 or later. Most of those had mustered in during the spring of 1864

and had no more experience than the black soldiers in Ferrero’s division. Two

of the seventeen were heavy artillery with twelve companies each rather than an

infantry regiment’s ten; three others were dismounted cavalry, also with twelve

companies each. These regiments served to increase the size of the IX Corps,

but they added little to its experience. The proportion of veteran soldiers was

even smaller than the presence of the twenty older regiments would suggest,

for disease and battle had thinned their ranks and the draft had only partly lled

them again. “Imagine a thousand men, exposed to wind & weather, dust, smoke

46

Ibid., pp. 58 (“instructed”), 136 (“by the right”), and pt. 3, p. 304 (“the proposed”); Lt Col J.

Perkins to Maj C. W. Foster, 23 Jul 1864, 19th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA; Rogall Diary, 26 Jul

1864; Report of the Joint Committee, 2: 106; Edward A. Miller Jr., The Black Civil War Soldiers

of Illinois: The Story of the Twenty-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry (Columbia: University of South

Carolina Press, 1998), p. 55 (“built two”); Noah A. Trudeau, Like Men of War: Black Troops in the

Civil War, 1862–1865 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1998), p. 232.

Virginia, May–October 1864

359

& battle—for two years, . . . sifted down to a hundred & fty sunburnt hardy fel-

lows,” Assistant Surgeon Merrill told his father, “and you will get an idea of one

of [these] regiments.”

47

The IX Corps had added nearly thirteen thousand soldiers since the previ-

ous October, trebling its size to nineteen thousand two hundred fty ofcers

and men present for duty in April 1864. Nearly two-thirds of them, however,

had spent only a few weeks in the Army. In this respect, the IX Corps was far

worse off than the rest of the Army of the Potomac, which had increased in

size by only 27.5 percent during the same six months to 102,869 of all ranks

present for duty. As a result, the proportion of new men in the rest of Meade’s

army only slightly exceeded one-fourth. As the three-year enlistments of 1861

began to run out, the “sunburnt hardy fellows” in the IX Corps became increas-

ingly rare, their places taken by conscripts, substitutes, and men who enlisted

for bounty money. A sizable minority of the men in the ranks had been under

arms no longer than those in the Union Army at Bull Run during the rst sum-

mer of the war. This was the organization with which Burnside was supposed

to capture Petersburg.

48

Ledlie’s division left its campground before 1:00 a.m. on 30 July and was

in the Union front line when the mine exploded at about 4:45, a few minutes

before sunrise. Captain Carter of General Hinks’ staff watched the explosion

from behind the Union lines. He saw the earth “rise gradually and as though it

was hard work to start at rst, and then leaping up to a height of 150 feet,” he

told his wife:

Imagine a pile of earth the size of a half acre going up the distance I have de-

scribed with cannon, horses, human beings and all, and then the whole falling

together in a mass of ruins, men buried alive, others half-buried and some with

their heads and upper part of their bodies buried and the rest remaining exposed.

The rebs were completely surprised.

49

The blast created a hole some two hundred feet long and fty wide where the

Confederate trench had been. The crater was twenty-ve or thirty feet deep, with

a lip of loose earth that rose about twelve feet above the ground that surrounded it.

Stunned and fearful, the men of Ledlie’s leading brigade lingered in their trenches

for ve minutes or more before climbing out and moving forward. The one veteran

regiment in that brigade had joined the IX Corps only in April. Two of the others,

both heavy artillery acting as infantry, had mustered in only seven months and

three months earlier and had also joined the corps that spring. The fourth regiment

47

OR, ser. 1, 6: 237; 9: 381; vol. 12, pt. 2, pp. 261–62; vol. 19, pt. 1, pp. 177–78; 21: 52–53;

vol. 24, pt. 2, p. 149; vol. 29, pt. 1, p. 226. C. G. G. Merrill to Dear Father, 23 Jun 1864, Merrill

Papers.

48

OR, ser. 1, vol. 31, pt. 1, pp. 811–13; 33: 1036, 1045; vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 228–30. For dates of

service of individual regiments, see Dyer, Compendium. A social prole of the men who joined the

new regiments is in Warren Wilkinson, Mother, May You Never See the Sights I Have Seen: The

Fifty-seventh Massachusetts Veteran Volunteers in the Army of the Potomac, 1864–1865 (New

York: Harper & Row, 1990), pp. 10–12.

49

S. A. Carter to My own darling Emily, 31 Jul 1864, Carter Papers.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

360

in the brigade was still recruiting, having managed to ll only six of its companies

by late May.

50

Two of the ve regiments in the second brigade of Ledlie’s division had served

with the IX Corps since 1862, but the other three had completed organization only in

April. It was natural that these new troops, recalling the 35 percent casualties that the

army had suffered during May and June followed by weeks of trench warfare, reverted

to what Burnside called “the habit, which had almost become second nature, of pro-

tecting themselves from the re of the enemy” by crowding into the crater. The men

of Lieutenant Verplanck’s old regiment in Hinks’ division were not the only soldiers

who wanted to stay “as close to the ground as they could get.” General Ledlie’s absence

did not help. Surgeon Hamilton E. Smith testied afterward that Ledlie spent time that

day at an aid station of General Willcox’s division, asking for “stimulants” to treat his

malaria. After a while, the general added a bruise from a spent rie ball to the list of

his maladies.

51

The month had been dry and hot, with afternoon temperatures sometimes above 95

degrees. By 30 July, no rain had fallen around Richmond for six days, and the shower

that fell then had been only the third of the month. Dust from the drought joined smoke

from the explosion hanging in the air as two more divisions of the IX Corps tried to nd

50

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 246, 527, 535, 539, 547, 558, 563 (diagram); Report of the Joint

Committee, 2: 19, 39, 77, 79, 107; Dyer, Compendium, passim.

51

OR, ser. 1, vol. 40, pt. 1, pp. 60 (“the habit”), 104, 118–19, 177, 527, 541, 547, 564. R. N.

Verplanck to Dear Mother, 27 Jul 1864, Verplanck Letters.

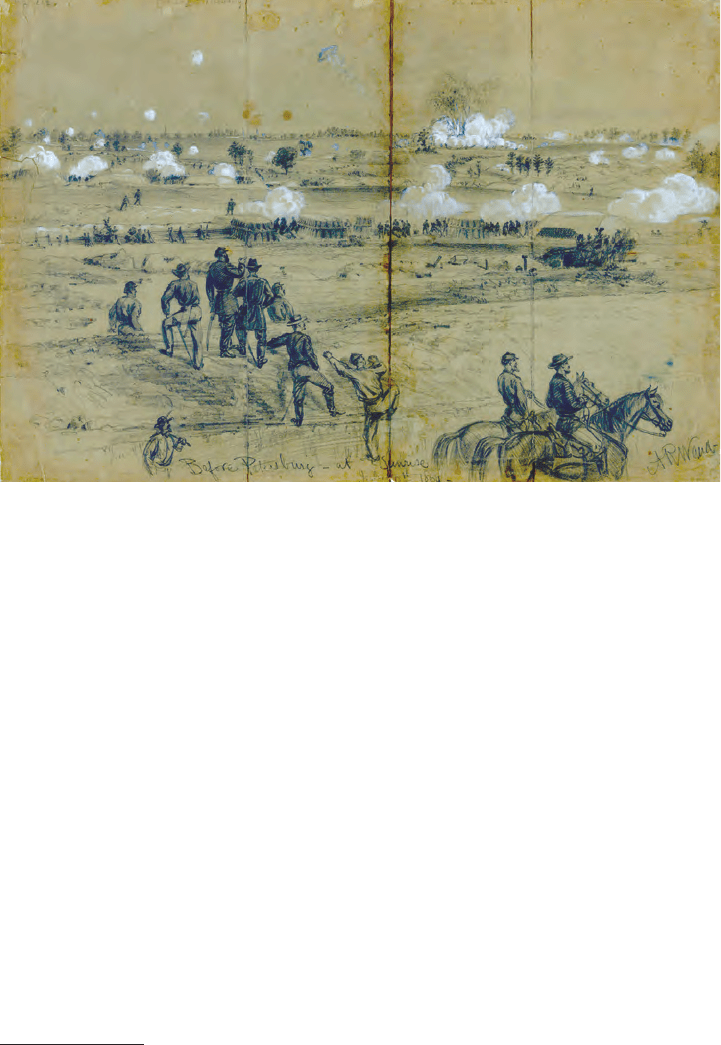

This drawing by Alfred R. Waud shows the explosion of the Petersburg mine in the

right-center distance.