Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

261

work on the road, progress in laying track far outstripped progress in recruiting

black soldiers. While black laborers earned no more than black soldiers, many

former slaves in Tennessee and throughout the South still found civilian labor

more attractive than submission to military discipline.

4

On 13 August 1863, the secretary of war dispatched Maj. George L. Stea-

rns to Nashville “to assist in recruiting and organizing colored troops.” Stearns

was a New England abolitionist, a nancial backer of John Brown who had

helped to organize the shipment of ries to Kansas during the 1850s, and a

friend of Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew. When it came time to raise

the 54th and 55th Massachusetts in the spring of 1863, Stearns canvassed the

states outside New England so effectively that Secretary of War Stanton ap-

pointed him a major and assigned him to begin black recruiting in and around

Philadelphia. By the end of the war, eleven regiments of U.S. Colored Troops

had left Philadelphia for the front, but the second of these was still only half

organized in August 1863 when Stearns received further orders from Stanton,

this time to report to Nashville.

5

Before Stearns left Philadelphia, he sent Stanton a long letter in which

he asserted “that my [recruiting] agents to be effective must be as heretofore

entirely under my control.” Stearns intended to operate in Tennessee as he had

in Pennsylvania, paying civilian agents with funds raised by a group of New

England philanthropists. Arriving in Nashville on 8 September with twenty

thousand dollars, he reported at once to General Rosecrans, who ordered him

to “take charge of the organization of colored troops in this department.” Al-

though Rosecrans’ order to “take charge” contradicted both the language and

the sense of Stanton’s instructions “to assist,” Stearns thus gained the full au-

thority that he craved. Only nine days passed before Governor Johnson com-

plained to the secretary of war about the new recruiter’s activities. “We need

more laborers now than can be obtained . . . to sustain the rear of General

Rosecrans’ army,” Johnson wrote. “Major Stearns proposes to organize and

place them in [a military] camp, where they, in fact, remain idle. . . . All the

negroes will quit work when they can go into camp and do nothing. We must

control them for both purposes.” Johnson’s concern about controlling the labor

of newly freed black people, based on the mistaken idea that they preferred

idleness to work, was common among federal authorities in all parts of the

South. The state’s Unionist government was just establishing itself, the gover-

nor continued. “It is exceedingly important for this . . . to be handled in such a

4

Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton, 1989), pp.

166–68. See, for instance, Col H. R. Mizner to A. Johnson, 3 Sep 1863, in The Papers of Andrew

Johnson, ed. Leroy P. Graf et al., 16 vols. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1967–2000),

6: 343, 353–54, 377, 417 (hereafter cited as Johnson Papers). Ofcers organizing black regiments

at Nashville and Gallatin reported violence directed against their recruits by white soldiers from

Kentucky and Tennessee. Capt R. D. Mussey to 1st Lt G. Mason, 14 Mar and 4 Apr 1864; to Capt G.

B. Halstead, 23 May 1864; to D. K. Carlton, 26 Jun 1864; all in Entry 1141, Dept of the Cumberland,

Org of Colored Troops, Letters Sent (LS), pt. 1, Geographical Divs and Depts, Record Group (RG)

393, Rcds of U.S. Army Continental Cmds, National Archives (NA).

5

OR, ser. 3, 3: 676–77 (quotation, p. 676), 682–83.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

262

way as will do the least injury.” In other words, Johnson wanted no New Eng-

land abolitionists recruiting in his state.

6

Stanton reacted as Johnson had hoped. Telegrams from Washington to the gov-

ernor and the recruiter arrived in Nashville the next day, reafrming that Stearns’

assignment was “to aid in the organization of colored troops under [Johnson’s] di-

rections and the directions of General Rosecrans.” If Stearns could not conform to

these instructions, Stanton added, he “had better leave Nashville and proceed to

Cairo to await orders.” This would remove him entirely from the Department of the

Cumberland. Stearns seemed to take the admonition in good part. On 24 Septem-

ber, he reported that recruiting had begun “with good success.” Only twelve days

passed, though, before Johnson complained that Stearns’ recruiters had raided “the

rendezvous of colored laborers and [taken] away some three hundred hands” who

had come to work expecting to lay track on the Nashville and Northwestern. The

conict between Stearns and Johnson eventually required an order from Stanton that

settled matters in the governor’s favor. Stearns left Nashville that fall, replaced by

his assistant, Capt. Reuben D. Mussey. Once again the federal government estab-

lished rival and conicting authorities to organize Colored Troops, as it had done

elsewhere in the occupied South, forcing recruiters to compete with the Army’s staff

departments—engineers, quartermasters, and commissaries of subsistence—for the

services of black workers.

7

Stearns himself had been opposed to the press-gang approach in recruiting black

soldiers. Impressment caused the unwilling to “run to the woods,” he told Stanton,

“imparting their fears to the Slaves thus keeping them out of our lines, and we get

only those who are too ignorant or indolent to take care of themselves.” Nevertheless,

impressment was common in the Department of the Cumberland, as it was elsewhere

in the occupied South. In October, Stearns’ agent at Gallatin reported that “every

Negro who comes in from the Country is brought by the picket parties . . . to this

ofce”—in other words, outpost guards brought men to the recruiter at gunpoint. In

February 1864, a “conscripting party” seized “nearly all the negro force” working

on the Tennessee and Alabama Railroad near Columbia. That fall, Captain Mussey’s

annual report stated that in the search for black recruits “none were pressed,” but the

unpublished correspondence of his own ofce told a different story.

8

Evidence of further confusion in federal recruiting efforts was the numbering

system used for the new organizations. Authorities in Nashville called the rst two

the 1st and 2d U.S. Colored Infantry regiments. Their men came from the Depart-

6

Ibid., pp. 683 (“that my”), 786 (“take charge”), 820 (“We need”); Maj G. L. Stearns to Capt C.

W. Foster, 5 Aug 1863 (S–94–CT–1863), and to E. M. Stanton, 17 Aug 1863 (S–114–CT–1863), both

led with (f/w) S–18–CT–1863, Entry 360, Colored Troops Div, Letters Received (LR), RG 94, Rcds

of the Adjutant General’s Ofce, NA.

7

OR, ser. 3, 3: 823 (“had better”), 876; Maj G. L. Stearns to Maj C. W. Foster, 24 Sep 1863

(“with good”) (S–176–CT–1863, f/w S–18–CT–1863), Entry 360, RG 94, NA; A. Johnson to Maj G.

L. Stearns, 6 Oct 1863 (“the rendezvous”), Entry 1149, Rcds of Capt R. D. Mussey, pt. 1, RG 393,

NA; Dudley T. Cornish, The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861–1865 (New York:

Longmans, Green, 1956), pp. 326–28; Peter Maslowski, Treason Must Be Made Odious: Military

Occupation and Wartime Reconstruction in Nashville, Tennessee, 1862–65 (Millwood, N.Y.: KTO

Press, 1978), pp. 102–07.

8

OR, ser. 3, 4: 476 (“none were”); Maj G. L. Stearns to E. M. Stanton, 17 Aug 1863 (“run to”)

(S–114–CT–1863, f/w S–18–CT–1863), Entry 360, RG 94, NA; J. N. Holmes to Maj G. L. Stearns,

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

263

ment of the Cumberland, east of the Tennessee River. West of the river lay Maj. Gen.

Ulysses S. Grant’s Department of the Tennessee, which also included most of the

state of Mississippi and adjoining parts of Arkansas and Louisiana. The plantation

country of West Tennessee was home to more than 36 percent of the state’s black

residents; recruiting there was the responsibility of Adjutant General Thomas. The

two black infantry regiments organized at La Grange were called the 1st and 2d

Tennessee (African Descent [AD]). While the ranks of all these regiments lled,

between June and November 1863, recruiters in and around Washington, D.C., were

raising two other regiments known as the 1st and 2d United States Colored Infantries

(USCIs). Not until October did a monthly return from the Department of the Cum-

berland reach the Adjutant General’s Ofce in Washington and alert administrators

to the problem. The two eastern infantry regiments kept their designations; and since

nine others raised in Arkansas, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia had al-

ready received consecutive numbers, the two regiments from the Department of the

Cumberland became the 12th and 13th USCIs.

9

The 12th lled the last of its ten companies in August 1863. By the end of

September, more than three hundred of its ofcers and men were guarding Elk

River Bridge, halfway between Nashville and Chattanooga on the rail line that sup-

plied Union troops in southeastern Tennessee. The Army of the Cumberland, after

a stunning defeat at Chickamauga Creek in Georgia in mid-September, retreated

to its base at Chattanooga, where victorious Confederates occupied the heights

around the city. As the XI and XII Corps arrived in Tennessee from the Army of

the Potomac to help relieve the besieged garrison, the 12th USCI left Elk River

and moved north. Toward the end of October, the regiment took station near the

Nashville and Northwestern end-of-track about thirty miles west of the state capi-

tal. The few companies of the 13th USCI that had enough men to be mustered into

service were already there. Their rst tasks had been to entrench their position, to

provide guards for railroad surveyors operating miles in advance of construction

gangs, and to send foraging parties through the surrounding country to secure feed

for the horses and mules. The 13th had no men to spare, Lt. Col. Theodore Trauer-

nicht complained, either for its planned labor on the railroad or to protect nearby

Unionist civilians, who were “kept continually in a state of terror by small bands of

guerrillas and horse-thieves.” The regiment needed more recruits. “Give me a full

regiment,” he wrote, “and we can do much good . . . ; as we are, I fear we can only

be an expense to the Government.”

10

Four days later, Trauernicht was in a better mood. “The command is doing well,”

he reported, “indeed under the circumstances much better than I expected.” The work

of fortifying the camp was done, and the troops felt “comparatively safe now. We

12 Oct 1863 (“every Negro”), and J. M. Nash to A. Anderson, 23 Feb 1864 (“conscripting”), both in

Entry 1149, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Maslowski, Treason Must Be Made Odious, pp. 100–101.

9

Maj C. W. Foster to Maj G. L. Stearns, 17 Oct 1863 (S–335–CT–1863, f/w S–18–CT–1863),

Entry 360, RG 94, NA. The 1st and 2d Tennessee (African Descent) became the 59th and 61st United

States Colored Infantries (USCIs) in March 1864. The future 14th, 15th, and 16th USCIs began their

existence as Major Stearns’ 3d, 4th, and 5th regiments. Maj T. J. Morgan to Maj G. L. Stearns, 30

Oct 1863, and Lt Col M. L. Courtney to Maj G. L. Stearns, 16 Nov 1863, both in Entry 1149, pt.

1, RG 393, NA; U.S. Census Bureau, Population of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.:

Government Printing Ofce, 1864), pp. 466–67.

10

OR, ser. 1, vol. 30, pt. 1, p. 170, and pt. 4, pp. 482 (“kept continually”), 483 (“Give me”).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

264

have alarms every night and the greatest vigilance is necessary on our part of prevent

our men being picked off by rebels who prowl around our lines after dark and seem

to have a great animosity towards the colored soldier.” Despite the lack of opportu-

nity for drill and instruction, the men seemed to be adapting to military life and “do

their duty well.”

11

By late November, the 13th USCI had moved its camp to Section 49, “the most

advanced post” on the Nashville and Northwestern, Col. John A. Hottenstein report-

ed. The end-of-track stood nineteen miles west of where it had been on 19 October.

Construction gangs had managed to lay only half a mile of track a day for thirty-

eight days, even though the 13th USCI nally had enough men to help in the work.

On 27 November, Hottenstein asked for the last one hundred recruits needed to ll

the regiment, explaining, “I have to work the men very hard. . . . It is impossible to

recruit here and the country is full of the enemy.” Local whites were likely to kill

any potential recruits who tried to reach the regiment’s camp on their own. Despite

the colonel’s complaints, the regimental adjutant was optimistic, even cheerful, nine

days later when he reported, “Everything ‘goes bravely on’ [one half of the regiment]

is detailed to work on R.R. for the ensuing week, the other does guard, foraging and

other duties. No enemy of any consequence in the vicinity.”

12

Harassment from Confederates was not the only impediment that track crews

faced. Early in January 1864, Col. Charles R. Thompson of the 12th USCI reported

that about one hundred of his men lacked shoes. “If there is any prospect of our get-

11

Lt Col T. Trauernicht to Capt R. D. Mussey, 23 Oct 1863 (misled with 2d USCI), Entry 57C,

Regimental Papers, RG 94, NA.

12

Col J. A. Hottenstein to Maj G. L. Stearns, 27 Nov 1863 (“the most”), Entry 1149, pt. 1, RG 393, NA;

1st Lt J. D. Reilly to Capt R. D. Mussey, 6 Dec 1863 (“Everything”), 13th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA.

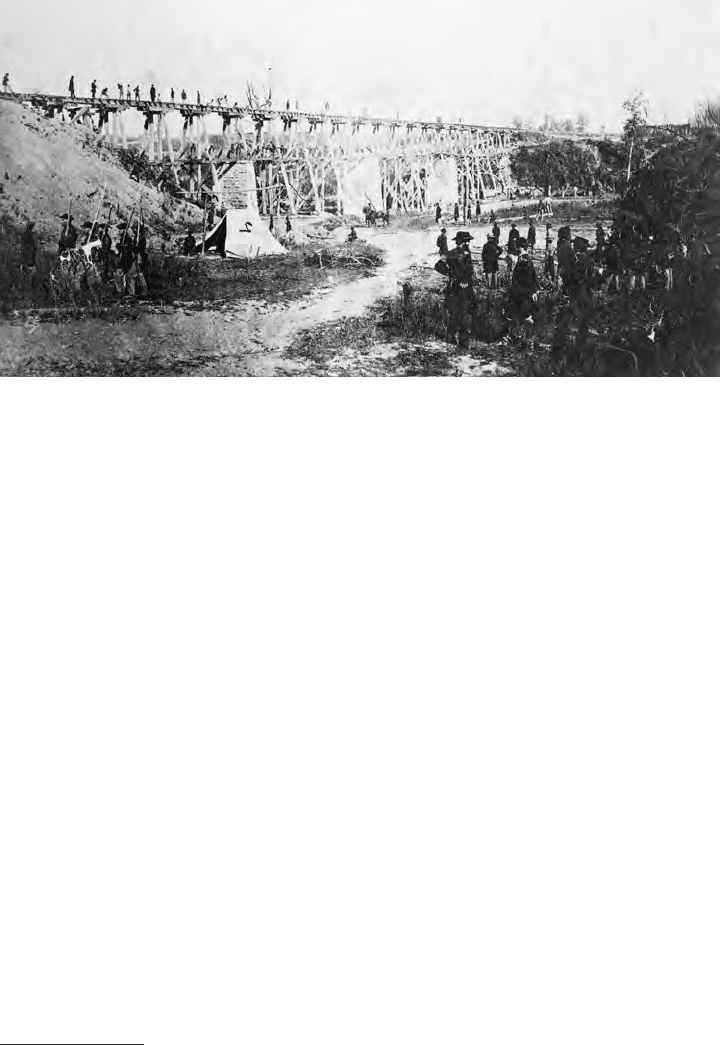

Railroad bridge over Elk River, between Nashville and Chattanooga, where the 12th U.S.

Colored Infantry stood guard in September 1863

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

265

ting a supply of shoes we can help on the work here materially,” he told Brig. Gen.

Alvan C. Gillem, who commanded all troops on the Nashville and Northwestern

Railroad. Thompson had to threaten to relieve his regimental quartermaster, but the

men got their shoes. By the end of January, thirty-four miles of track had been laid,

and by late March, the chief quartermaster in Nashville was ordering construction of

storehouses and a levee at Reynoldsburg, at the other end of the line. The Nashville

and Northwestern track was completed to the Tennessee River well before shallow

water barred steamboats from the Cumberland.

13

Although the ranks of both regiments nally lled, recruiting of Colored

Troops in the Department of the Cumberland lagged. In October 1863, one of

Stearns’ civilian agents wrote from Clarksville, about forty-ve miles northwest

of Nashville, that previous commanders of the Union garrison had always turned

away escaped slaves who sought refuge there. Since the new colonel approved of

attempts to recruit black soldiers, the agent said, “There is now here about one

hundred thirty [who] are anxious to enlist. . . . I think they will come in now fast.”

At Gallatin, the same distance northeast of Nashville, 203 recruits were waiting for

tents and overcoats. Besides shelter and clothing, the agent there requested blank

forms for certicates of enlistment that the former slaves could leave with their

wives. The documents would entitle soldiers’ families to federal protection “if

their masters abuse them.” A third agent wrote from a federal garrison twenty-ve

miles south of Murfreesborough that “no men can be got outside [the Union lines]

without a military escort for protection.” The parlous state of the post’s defenses

had not stopped him from signing up “as many as . . . possible” of the twenty or

thirty black civilians laboring on the earthworks.

14

The Union Army would need all the labor it could hire to sustain the coming

year’s advance into the heart of the Confederacy. In the fall of 1863, federal divisions

from places as distant as Maryland and Mississippi had converged on Chattanooga

by rail to raise the siege and turn the Confederates back into northern Georgia. Rose-

crans was gone as commander of the Department of the Cumberland and its eld

army; in his place was Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, a Unionist Virginian who had

grown up in a slave-holding family. Grant, who had organized the relief of Chat-

tanooga, went east in March 1864 to assume command of all the Union armies. His

successor in the region between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, Maj. Gen.

William T. Sherman, commanded the Military Division of the Mississippi, which

included the Armies of the Cumberland, the Ohio, and the Tennessee. Each army

represented a geographical department of the same name; taken together, their troop

strengths amounted to more than 296,000 men present. Nearly two-thirds of those

served in garrisons or in guard outposts along the region’s railroads. “If I can put

in motion 100,000 [men] it will make as large an army as we can possibly supply,”

Sherman told Grant. Sherman’s staff calculated that the spring campaign against

Atlanta would require one hundred thirty carloads of freight a day to keep the armies

13

OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 2, p. 269, and pt. 3, p. 155; Johnson Papers, 6: 701; Col C. R. Thompson

to Brig Gen A. C. Gillem, 8 Jan 1864 (quotation), 12th USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

14

C. B. Morse to Maj G. L. Stearns, 22 Oct 1863 (“There is”); J. H. Holmes to Maj G. L. Stearns,

8 Oct 1863 (“if their”); W. F. Wheeler to Maj G. L. Stearns, 4 Oct 1863 (“no men”); all in Entry 1149,

pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

266

in the eld. One thousand freight cars and one hundred locomotives would be neces-

sary to handle this volume of trafc.

15

The need for railroad track layers, for teamsters to haul goods beyond the rail

line, and for full crews to maintain roads over which the teamsters’ wagons rolled

was apparent to Union generals west of the Appalachians. Late in November 1863,

as Grant prepared to drive the Confederates from the heights around Chattanooga,

he took time to order Brig. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge to “impress negroes for all the

work you want from them” to repair the railroad near Pulaski, Tennessee. Early the

next month, Dodge reported that he had enough men to repair bridges and right of

way, but that he faced stiff competition from recruiters. “The . . . ofcers of colored

troops claim the right to open recruiting ofces along my line; if this is done I lose

my negroes. . . . So far I have refused to allow them to recruit. They have now re-

ceived positive orders . . . to come here and recruit. I don’t want any trouble with

them, and have assured them that when we were through with the negroes I would

see that they go into the service. . . . Please advise me.” Grant at once told Dodge to

arrest any recruiters who interfered with his track crews. Generals in the eld thought

that preparation for the coming year’s operations was more important than the War

Department’s policy of putting black men in uniform. An advance into mountainous

northern Georgia, where the Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennes-

see had retreated after its defeat at Chattanooga, would take Union troops beyond

navigable rivers and force them to rely more than ever on wheeled transportation.

16

Confederate leaders knew this well. All through the fall of 1863, while Grant and

Sherman moved to relieve the beleaguered Union garrison at Chattanooga, Bragg

and General Joseph E. Johnston, who between them had charge of all Confederate

troops between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, urged their cavalry command-

ers to strike “the advancing columns of the enemy, . . . breaking his communications,

and if possible throwing a force north of the Tennessee to strike at the enemy’s rear.”

The result was a series of raids on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, one of the

Confederacy’s longest.

17

The track operated by the Memphis and Charleston ran east from Memphis

through the southern tier of Tennessee counties and dipped down to Corinth, Mis-

sissippi. It crossed the Tennessee River at Decatur, Alabama, met the track of the

Tennessee and Alabama just beyond the river, and ran on through Huntsville to end

at Stevenson. From there, the Nashville and Chattanooga and a series of shorter lines

offered connections eastward to Atlanta, Savannah, and Charleston. In late October,

Confederate Maj. Gen. Stephen D. Lee’s cavalry struck the Memphis and Charleston

at Tuscumbia, forty miles west of Decatur, and several other points along the line

in northern Alabama. A week later, Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers’ command, two

15

OR, ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 3, pp. 469 (quotation), 550, 561, 569; Christopher J. Einolf, George

Thomas: Virginian for the Union (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001), pp. 13, 15, 18–21,

74; William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, 2 vols. (New York: D. Appleton,

1875), 2: 9–12.

16

OR, ser. 1, vol. 31, pt. 3, pp. 220 (“Impress negroes”), 367 (“The . . . ofcers”). The Tennessee

and Alabama was also known as the Central Alabama and the Nashville and Decatur.

17

OR, ser. 1, vol. 30, pt. 4, p. 763 (quotation); vol. 31, pt. 3, pp. 594, 610. Peter Cozzens, The

Shipwreck of Their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga (Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

1994), pp. 34–35.

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

267

small brigades amounting to some seventeen hundred men, attacked three stations

within forty miles of Memphis. Neither raid did any lasting damage.

18

In mid-November, Confederate mounted troops throughout the region readied

themselves for another assault on the Union lines of communications. By the time

preparations were complete, Grant’s armies had broken the siege of Chattanooga

and driven Bragg’s troops into northern Georgia. Swollen rivers impeded the prog-

ress of the Confederate cavalry, but the expedition was under way by the end of

the month. General Chalmers led three small brigades out of Oxford, Mississippi,

and on 4 December reached Moscow, Tennessee, on the Memphis and Charleston.

Chalmers told Col. Lawrence S. Ross and his Texans to burn the railroad bridge

that spanned the Wolf River.

19

The bridge guard at Moscow was the 2d Tennessee (AD), camped west of town

near where the railroad and a wagon road crossed the river. The regiment had mus-

tered in its last four companies as recently as late August, after an expedition returned

with two hundred ten recruits, but it had not been idle since. A bridge guard did not

lead a passive existence. It was responsible for detecting and suppressing enemy

activity, intercepting Confederate mail service, and capturing furloughed soldiers

during their visits home. Company G’s Record of Events, entered on the bimonthly

muster roll, described one capture tersely:

November 25 1863 Capt [Henry] Sturgis with 40 men from the company marched

to Macon Tenn, starting from camp at 6 o’clock P.M. Captured Lt [Joseph L.] New-

born, 13” Tenn Infty (Rebel) one Colts Navy Revolver, one Mule saddle & equip-

ments. Returned to camp at 4 o’clock A.M. November 26. Slight skirmishing while

returning. No loss. Distance marched twenty miles.

20

Just a week after Company G’s night march, a few Confederate cavalry

appeared in midafternoon, “dashing up on the gallop even to the bridge, and

ring on the pickets stationed there,” Col. Frank A. Kendrick reported. A local

Unionist had told Kendrick four days earlier that mounted Confederates were

on the move. Since then, the men of the regiment had been especially wary,

removing the planks of the wagon bridge and replacing them only when the

guard allowed trafc to approach. Unable to cross the dismantled bridge, the

Confederates rode off.

21

The next day, 4 December, heavy smoke appeared on the western horizon

not long after noon. Kendrick conferred with ofcers of the 6th Illinois Cav-

alry, who arrived about that time in advance of a column moving to intercept

the Confederate force. They decided that the enemy must have avoided Mos-

cow and gone on toward La Fayette, some eight miles to the west. When the

18

OR, ser. 1, vol. 31, pt. 1, pp. 25–31, 242–54, and pt. 3, pp. 746–47; Robert C. Black III, The

Railroads of the Confederacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998 [1952]), pp.

5–6.

19

OR, ser. 1, vol. 31, pt. 1, pp. 589–90, and pt. 3, pp. 704–05, 865.

20

Ibid., pt. 3, p. 190; Maj E. R. Wiley Jr. to “Captain,” 24 Aug 1863, 61st USCI, Entry 57C, RG

94, NA; NA Microlm Pub M594, Compiled Rcds Showing Svc of Mil Units in Volunteer Union

Organizations, roll 212, 61st USCI (quotation).

21

OR, ser. 1, vol. 31, pt. 1, p. 583 (“dashing up”), and pt. 3, p. 276.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

268

planks on the wagon bridge were laid in place, the 6th Illinois Cavalry moved

on in pursuit, followed closely by another cavalry regiment and the column’s

artillery. Soon afterward, the men of the 2d Tennessee (AD) heard ring and

the 6th Illinois Cavalry reappeared “in much disorder,” as Kendrick described

the scene. “The bridge soon became obstructed with artillery, caissons, and

wagons from the train which had got over, and great numbers of the retreating

cavalry plunged headlong into the river, which, though narrow, is deep and

rapid, and many men and horses were thus lost.”

22

The ofcer commanding the 7th Illinois Cavalry, the third regiment in the col-

umn, agreed with Kendrick:

When we got to the bridge it was so clogged with horses, ambulances, wagons, and

artillery that it was almost impossible to get a man across it. Several of the horses

had broken through the bridge and were [stuck] fast, and the bridge was so torn up

that it was impossible to clear it. I ordered my men across, and succeeded by jump-

ing our horses, crawling under wagons and ambulances, &c., in getting about 50

men across. . . . Several were knocked off the bridge into the river. I found it impos-

sible to get any more men across without their swimming, which so injured their

ammunition as to nearly render it useless.

By this time, Kendrick had reinforced the guard on the wagon bridge and sta-

tioned two companies at the railroad bridge, some three hundred yards away.

The balance of the regiment, with a few cannon, occupied an earthwork that

commanded both bridges. Confederate cavalry appeared, rst at the wagon

bridge and soon afterward at the railroad bridge. The 2d Tennessee (AD) de-

fended both, while the 7th Illinois Cavalry struggled to rescue the artillery

that had crossed the wagon bridge. After an hour of ghting, sometimes hand

to hand, the cavalrymen managed to retrieve the cannon, and the entire Union

force was once more on the east side of the river. All the while, men of the

2d Tennessee (AD) who had been detailed to serve the cannon directed re

from their fort at the attacks on both bridges. As cavalry on both sides usually

did, the Confederates had left their horses in the care of every fourth trooper

while the remaining three men advanced to ght on foot. After several artillery

rounds landed among the horses, the Confederate force withdrew.

23

Such raids by organized bodies of Confederates rarely troubled construc-

tion crews along the Nashville and Northwestern track, which lay more than

one hundred miles northeast of the Memphis and Charleston, but sporadic at-

tacks by enemy irregulars required vigilance. “We have alarms every night,”

Colonel Trauernicht reported from a camp of the 13th USCI. During one of

several attacks in November, a shot red by “guerrillas” wounded Sgt. Joshua

Hancock of the 12th USCI while he commanded an outpost on the railroad

thirty-eight miles west of Nashville. Both regiments spent that fall and winter

guarding the railroad and sometimes furnishing crews to lay track while other

22

Ibid., pt. 1, p. 584.

23

Ibid., p. 586.

Middle Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, 1863–1865

269

black regiments in the Department of the Cumberland continued to struggle to

ll their ranks.

24

Since the Emancipation Proclamation exempted Tennessee from its provi-

sions, the effort to enlist black soldiers there was a more complicated matter

than it was farther south. Recruiting parties went out with instructions to “im-

press all able bodied negroes under 35 years of age,” but local slaveholders

proclaimed their personal loyalty to the Union in hopes of saving their human

property. “I am likely to get myself into hot water in this business of impress-

ment,” Lt. Col. Charles H. Pickering of the 17th USCI admitted. White troops

at La Vergne, between Nashville and Murfreesborough, had recently arrested

an entire company from Pickering’s regiment and released six black recruits

“gathered up” in the neighborhood, as well as a white man the company com-

mander had arrested “for having, with violence, opposed the detachment sent

to take his slaves.” The company commander had left Pickering’s written in-

structions in camp and could show no authority for seizing the slaves, so the

white troops returned them to their master. Union ofcers elsewhere in the

Department of the Cumberland also interfered with attempts to gather black

recruits by force.

25

Impressment was not a selective way to get men. At Gallatin, Col. Thomas

J. Morgan found that “not one” of the recruits for the 14th USCI had undergone

medical examination. “In view of the informal and unsatisfactory manner in

which the entire work has been performed,” he wrote, “I propose to commence

at the beginning, subject every man to a rigid examination, and take none who

are t only for the lling of hospitals.” Captain Mussey, in charge of black re-

cruiting in the Department of the Cumberland since Major Stearns’ falling out

with Governor Johnson, planned to use the 42d and 101st USCIs as “invalid

or laboring regiments, composed of men unt for eld duty but t for ordinary

garrison duty,” similar to the 63d and 64th USCIs on the lower Mississippi. As

mortality rates throughout the U.S. Colored Troops attested, not all command-

ers were so scrupulous. Unt men appeared in the ranks of all regiments, black

and white, throughout the war.

26

The U.S. Sanitary Commission, an investigative and advisory body com-

posed mostly of physicians, had surveyed two hundred of the new volunteer

regiments in the fall of 1861. Only eighty-four (42 percent) had offered recruits

what commissioners called “a thorough inspection” at the time of enlistment,

and only eighteen of those had backed up the initial examination with another

at the time of mustering in. (Normal peacetime procedure subjected recruits to

24

Trauernicht to Mussey, 23 Oct 1863 (“We have”); Lt Col E. C. Brott to Col A. A. Smith, 8 Jan

1864, 15th USCI; Lt Col M. L. Courtney to Capt R. D. Mussey, 24 Dec 1863 and 16 Jan 1864, 16th

USCI; Col W. R. Shafter to Capt R. D. Mussey, 28 Dec 1863, 17th USCI; all in Entry 57C, RG 94,

NA. NA M594, roll 207, 12th USCI (“Guerrillas”).

25

Ira Berlin et al., eds. The Black Military Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press,

1982), pp. 122–26. Col W. B. Gaw to Capt W. Brunt, 9 Feb 1864 (“impress all”), 16th USCI; Lt Col

C. H. Pickering to Capt R. D. Mussey, 13 Feb 1864 (“I am likely”), 17th USCI; Col W. B. Gaw to

Capt R. D. Mussey, 17 Feb 1864, 16th USCI; all in Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. Col T. J. Downey to Capt

R. D. Mussey, 24 Feb 1864, Entry 1149, pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

26

OR, ser. 3, 4: 765 (“invalid”); Col T. J. Morgan to Maj G. L. Stearns, 2 Nov 1863 (“not one”),

misled with 3d USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. For the 63d and 64th USCIs, see Chapter 6, above.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

270

examination at the place of enlistment, usually by a civilian doctor on contract,

and a second examination by the regimental surgeon before assignment to a

company.) The Sanitary Commission learned that the Army of the Potomac

alone had discharged more than eight hundred fty men within a few weeks’

time “on account of disabilities that existed at and before their enlistment, and

which any intelligent surgeon ought to have discovered on their inspection as

recruits.”

27

Although examiners in 1863 rejected nearly one-third of drafted men, black

and white, and more than one-quarter the next year, pressure to enlist black

Southerners to help ll Northern states’ draft quotas continued to ensure a high

number of unt recruits in the U.S. Colored Troops. As late as January 1865,

the 17th USCI transferred twenty-ve men to the 101st for a variety of causes,

including both youth and old age, as well as cases of rheumatism, hernia, back

injury, “heart disease,” and hemorrhoids. In May, the same regiment sent thirty

men to the 42d USCI, more than half of them complaining of rheumatism.

28

However perfunctory the physical examinations were, it was important to

organize the men and muster in the companies so that the quartermaster could

provide clothing and shelter in the middle of winter. “In their present condi-

tion they cannot live decently,” Lt. Col. Michael L. Courtney of the 16th USCI

reported from Clarksville, “nor are they learning to drill as they would if they

were provided with their arms, and at the present time, three companies have

to do all the guard duty.” Drill was important to ofcers because they wanted

to lead troops in the eld rather than spend time supervising quartermaster’s

details digging ditches or shifting freight. Colonel Morgan spoke for most of-

cers when he announced his intention “to put this Reg[imen]t . . . upon a War

footing.” His success at that became evident four months later when the depart-

ment commander, who had earlier expressed doubts about black men’s aptitude

for military service, appeared to be “exceedingly pleased with the 14th,” as

an ofcer in Nashville reported, “and [said] he [wished] he had a Brigade of

U.S.C.T.” Nor was Morgan’s the only new black regiment to receive compli-

ments about its appearance and discipline. When the 15th USCI marched from

Columbia to Shelbyville that December, civilians along the forty-mile route

commented on the troops’ avoidance of straggling and looting.

29

Despite all the difculties of raising fresh regiments—examining the re-

cruits, then clothing, housing, feeding, arming, and drilling them—the ranks

of the new black organizations lled during the winter. By spring 1864, the

27

U.S. Sanitary Commission, A Report to the Secretary of War of the Operations of the

Sanitary Commission, and upon the Sanitary Condition of the Volunteer Army . . . (Washington,

D.C.: McGill & Witherow, 1861), pp. 12, 14 (“a thorough”), 15 (“on account”).

28

Leonard L. Lerwill, The Personnel Replacement System in the United States Army (Washington,

D.C.: Department of the Army, 1954), pp. 47–49; Report of the Secretary of War, 1863, 38th Cong., 1st sess.,

H. Ex. Doc. 1 (serial 1,184), p. 123; Report of the Secretary of War, 1864, 38th Cong., 2d sess., H. Ex. Doc

83 (serial 1,230), p. 64; Special Order 4, 12 Jan 1865 (“heart disease”), and Special Order 30, 4 May 1865,

both in 17th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. Berlin et al., Black Military Experience, pp. 76–78, outlines the

shortcomings of the Union program of lling Northern states’ draft quotas with Southern recruits.

29

Courtney to Mussey, 16 Jan 1864 (“In their”). Capt R. D. Mussey to Col W. B. Gaw, 29 Feb 1864

(“exceedingly pleased”), 16th USCI; Col T. J. Morgan to Capt R. D. Mussey, 6 Dec 1863, 14th USCI; Col

T. J. Downey to Capt R. D. Mussey, 23 Dec 1863 and 8 Feb 1864, 15th USCI; all in Entry 57C, RG 94, NA.