Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

South Texas, 1864–1867

441

supposed to be in the vicinity of Redmond’s Ranche,” about forty miles upriver.

When the troops reached there on the morning of 14 August, residents could tell

them nothing of importance, but that afternoon “a Mexican came in” with the

news that he had seen Indians at his ranch, more than forty miles to the northeast,

far from the river. Having gone part of the way, and hearing that “a large force of

Cavalry” was moving from San Antonio toward the Rio Grande, Wright decided

the next morning to move northwest again, toward Laredo and the river. On the

morning of 17 August, the party arrived at a ranch some twenty-ve miles from

Laredo. “There I found a post of one Sergt and six men of the 2d Texas Cavalry,

who were scouting around the country,” Wright reported. This may have been the

“large force of Cavalry” he had heard about.

41

Having marched his men more than one hundred miles in six days, Wright

decided to let them rest while he rode on to Laredo. There, the lieutenant com-

manding a garrison of some two dozen men told him that the raiders were Mexican

Kickapoos. These Indians had been forced from their lands east of the Mississippi

River two generations earlier. Many had settled in Kansas, but some had moved to

Texas, only to be driven from there into Mexico ten or fteen years later. Others

from Kansas had joined them recently, disgusted by an 1862 treaty that demanded

further land cessions. The lieutenant at Laredo said that small bands of raiders had

driven off herds of cattle and horses and killed more than a dozen residents along

the river. Wright rejoined his command and marched back down the river to Roma,

arriving on 24 August. During the expedition he had learned that while residents

along the Rio Grande were clamoring for protection, raiding in Texas by Indians

amounted to little, compared to thefts by residents who drove herds across the

river. The commanding ofcer at Roma reported a band of marauders “painted and

disguised as Indians” killing residents and stealing livestock. Vague information,

demands for military protection, and complaints blaming property losses on Indian

raiders would all become familiar to soldiers charged with implementing federal

Indian policy in the West during the following decades.

42

Army ofcers soon learned to discount what General Sheridan called “exag-

gerated reports, gotten up in some instances by frontier people to get a market for

their produce, and in other instances by army contractors to make money.” Sheridan

believed in any case that warnings of raids on the Texas frontier were merely a ruse

to remove troops from the settlements so that former slaveholders could have a free

hand with the black population. The general commanding the Department of Texas

told Sheridan in July 1866 that he received “frequent complaints . . . of the barbarities

practiced towards . . . freedmen” but could do nothing about it for want of troops.

43

While staff ofcers planned the distribution of soldiers and supplies, enlisted

men and medical ofcers on the lower Rio Grande confronted scurvy, brought about

yet again by a lack of fresh meat and vegetables at Brazos Santiago. “You can have

no idea of our desperate situation,” Surgeon Merrill wrote to his father. “The idea of

41

Maj L. Wright to Capt R. C. Shannon, 24 Aug 1865, Entry 533, pt. 2, RG 393, NA.

42

Ibid.; Jackson to Wheeler, 13 Aug 1865 (“painted and disguised”); Craig Miner and William

E. Unrau, The End of Indian Kansas: A Study of Cultural Revolution, 1854–1871 (Lawrence:

Regents Press of Kansas, 1978), pp. 45–49, 96–98.

43

OR, ser. 1, vol. 48, pt. 1, p. 301 (“exaggerated reports”); “Condition of Affairs in Texas,” 39th

Cong., 2d sess., H. Ex. Doc. 61 (serial 1,292), p. 4 (“frequent complaints”).

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

442

putting ten thousand men in such a country without . . . making any provision is more

than preposterous—it is damnable—and I am perfectly disgusted with . . . the whole

affair. If they ask my opinion I shall tell them plainly. . . . I do not want to see my men

murdered by inches, when there is no necessity for any such thing.” Ofcers, Chap-

lain Johnson explained in a letter home, could afford supplements to their diet and

thus avoided the scurvy that aficted enlisted men. “We could buy canned Peaches

and Tomatoes . . . but the soldiers without money not being paid for six months had

to conne themselves to the regular army ration.”

44

The Quartermaster Department, which arranged shipping and hauling of military

supplies, had suffered from corruption on the lower Rio Grande since the Union army

had landed in the fall of 1863 and was slow to recover after General Weitzel and the

XXV Corps arrived. Neither were military administrators in Washington of much help.

The Adjutant General’s Ofce in Washington assured Sheridan, in New Orleans, that

the Subsistence Department would ship “a large quantity of potatoes and onions . . .

from St. Louis, Boston and New York, . . . which may be issued in lieu of other rations

allowed by law. The law does not authorize extra issues of these articles and the Com-

missary General of Subsistence considers the authorized ration sufcient.” Rather than

abide by a bureaucrat’s comments on “the law” and “the authorized ration,” the ofcer

commanding at Ringgold Barracks sent an expedition to the Nueces valley, some one

hundred fty miles to the north, that returned with two hundred fty head of cattle

bearing “brands of the late Rebel Government . . . and of one [Richard] King, late a

contractor for the so-called Confederate States.” The United States Sanitary Commis-

sion, a private charitable organization that operated under a federal charter, contributed

a barrel of pickles that traveled by boat from Brownsville to Ringgold Barracks and

from there fty miles overland to the garrison at Edinburg.

45

As happened wherever regiments, black or white, camped in one place for long,

enlisted men on the Rio Grande soon took measures of their own to supplement dietary

deciencies. By 7 August, “thieving and plundering” had become so common that the

brigade commander at Roma threatened to allow neighboring civilians “to shoot any

soldiers caught marauding or . . . molesting the citizens by the killing of their cattle,

destruction of water melon gardens, or trespassing upon their premises.” Residents of

Brownsville also complained, but the general in command there merely appointed a

board of ofcers to investigate claims and offered cash payments for proven damages.

In one case, three companies of the 8th United States Colored Artillery (USCA) split a

ne of seventy-ve dollars for “potatoes pillaged” from a local farmer.

46

Fortunately for the health of the troops, a remedy was available in native plants

of the region. As early as 10 July, Lieutenant Norton saw men of the 8th USCI eat-

ing the prickly pear, “a sort of cactus that grows all over this country. It looks like

44

Maj L. S. Barnes to Lt Col D. D. Wheeler, 5 Aug 1865, Entry 533, pt. 2, RG 393, NA;

Merrill to Dear Father, 2 Jul 1865; T. S. Johnson to My Dear People, 15 Aug 1865, Johnson Papers;

Humphreys, Intensely Human, pp. 125–41.

45

Maj Gen G. Weitzel to Maj G. Lee, 21 Dec 1865, and Col E. D. Townsend to Maj Gen P. H.

Sheridan, 25 Aug 1865 (“a large quantity”), both in Entry 4495, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Jackson to Wheeler,

13 Aug 1865 (“brands of the”); Brig Gen L. F. Haskell to Capt R. C. Shannon, 21 Aug 1865, Entry 533,

pt. 2, RG 393, NA.

46

3d Bde, 2d Div, XXV Corps, GO 20, 7 Aug 1865 (quotations), 116th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94,

NA; 1st Div, XXV Corps, Circular, 1 Jul 1865, Entry 533, pt. 2, RG 393, NA; Central Dist of Texas,

SO 177, 1 Sep 1865, 8th United States Colored Artillery (USCA), Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

South Texas, 1864–1867

443

a set of green dinner plates, the edge of one grown fast to the next. . . . The pears

grow round the edge of the plates, about the size and shape of pears, covered with

thorns and of a beautiful purple color when ripe, and full of seeds like a g. Most

of the men devoured them greedily, but I did not fancy their insipid taste.” Enlisted

men with a nutritional craving were not as fastidious as their better-fed ofcers.

47

Two weeks later, a letter went from XXV Corps headquarters to generals com-

manding divisions, extolling the properties of “the ‘Agave Americana’ or Ameri-

can Aloe, which is found in groves of greater or less sizes [and] will cure scurvy

or prevent it.” After giving instructions for rendering the juice, Weitzel ordered his

generals to “send out detachments from each post or brigade . . . to collect this tree

and make this drink, called by common people ‘Pulque.’ . . . Ascertain where the

trees can be found before starting the expedition, it is worth while even to send

even a hundred miles off for it.” By mid-August, regiments were sending entire

companies fty or sixty miles in search of aloes, otherwise known as maguey. The

incidence of scurvy decreased the next month, although some ofcers attributed

this to the recent arrival of potatoes in quantity. Still the disease persisted; in early

October, the surgeon of the 43d USCI reported that of 539 men in the regiment,

163 were excused from duty, “nearly all being cases of scurvy.”

48

The surgeon was concerned about the effect on scurvy patients of a few weeks’

shipboard diet, for the regiment was due to muster out and return to Philadelphia,

where it had been raised and where its ofcers and men would receive their dis-

charges and nal pay. Orders had arrived recently for the muster-out of all black

regiments from the free states. This was part of the program dismantling the Union

Army and cutting government expenses.

49

That June, a month after the last Confederate surrender, the War Department

had discontinued the Army of Georgia and the Army of the Potomac, two of the

Union’s premier ghting forces, mustering out most of the regiments in each. In

the same month, across the South, mustering out began of volunteer artillery bat-

teries and cavalry regiments, the two most costly arms of the service. With nearly

all of the soldiers who had marched with Sherman discharged and paid off, the War

Department discontinued the Army of the Tennessee and nearly all of the wartime

corps organizations on 1 August. The next step was to begin reducing the number

of infantry regiments that had not been part of the major eld armies but were

subordinate to regional commands or organized as corps, divisions, or brigades.

50

Although even the most senior of the black regiments was not due for muster-out

until early 1866, War Department administrators decided to begin with those that had

been raised in the free states, from Massachusetts and Rhode Island to Illinois and

47

Surgeon D. Mackay to Capt R. C. Shannon, 13 Aug 1865, Entry 533, pt. 2, RG 393, NA;

Norton, Army Letters, p. 271.

48

Maj Gen G. Weitzel to Maj Gen G. A. Smith et al., 26 Jul 1865 (“send out”), Entry 512, XXV

Corps, LS, pt. 2, RG 393, NA. Asst Surgeon J. L. Chipman to 1st Lt E. S. Dean, 2 Oct 1865, 43d

USCI, and Capt H. G. Marshall to Col T. D. Sedgwick, 25 Aug 1865, 114th USCI, both in Entry

57C, RG 94, NA; W. Goodale to Dear Children, 22 Aug 1865 (“nearly all”), Goodale Papers; T. S.

Johnson to My Dear People, 5 Jul 1865, Johnson Papers; E. W. Bacon to Dear Kate, 9 Sep 1865, E.

W. Bacon Papers, AAS.

49

OR, ser. 3, 5: 516–17; Mark R. Wilson, The Business of Civil War: Military Mobilization and

the State, 1861–1865 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), pp. 191–96.

50

OR, ser. 1, vol. 46, pt. 3, pp. 1301, 1315; vol. 47, pt. 3, p. 649.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

444

Iowa. At that time, some of those regiments occupied the Carolinas; some manned

posts along the Mississippi River; and eleven were in Texas. These were the 8th, 22d,

41st, 43d, 45th, and 127th USCIs, all from Philadelphia; the 28th USCI, from Indi-

ana; the 29th, from Illinois; the 31st, from New York; the 29th Connecticut Infantry;

and the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry. All of them left Texas that fall.

51

With the free-state regiments of the XXV Corps gone and other reductions to

come, the general commanding the Department of Texas made an unusual request.

He asked Weitzel to provide a list of the remaining regiments “in the order in which

they should be retained, according to your judgment of their qualities.” Seldom, if ever,

had the commander of more than a dozen black regiments been asked to rate them in

order of merit. Weitzel thought for a few days before replying and toward the end of

November submitted a list in descending order of merit (Table 4). At the top stood the

7th USCI, followed by the 9th, 46th, 62d, 38th, and 114th USCIs; the 2d United States

Colored Cavalry (USCC); the 36th, 19th, 10th, 117th, 109th, 116th, 118th, 115th, and

122d USCIs; the 1st USCC; and the 8th United States Colored Artillery (USCA).

52

What made the difference between a good regiment and a bad one, an organization

that Weitzel wanted to keep and one that he would gladly be rid of? One difference,

clearly, was sheer length of service, the number of months since a regiment had mus-

tered in. The rst nine regiments, those at the top half of Weitzel’s list, averaged nearly

two years of service. The nine in the bottom half of the list averaged slightly more than

one year and a quarter. Each regiment’s history of active service also inuenced its ef-

ciency. According to records compiled by the adjutant general, the 7th USCI, at the

head of the list, had taken part in eleven engagements, including some full-scale battles

around Richmond in the fall of 1864. The nine regiments in the top half of the list aver-

aged slightly more than four engagements each; those in the bottom half, fewer than

two. Length of time and variety of service therefore counted for a great deal.

Table 4 shows at once that some regiments varied wildly from the average. The

circumstances of each regiment’s service, and the personalities of its senior of-

cers, could have appreciable effects. After two companies of the 1st Arkansas (Af-

rican Descent [AD]) surrendered to a Confederate force at the Mound Plantation

in Louisiana, in May 1863, the remaining companies moved across the Mississippi

River to Vicksburg, where they became part of a large garrison. There, brought up

to strength and with all its companies stationed together, the 1st Arkansas (AD)

had ample opportunity to improve its drill; but the Mound Plantation remained its

only engagement throughout the war. In April 1864, it received a new designation

as the 46th USCI. Brig. Gen John P. Hawkins, who commanded at Vicksburg,

called it “my ‘show Regiment,’” and attributed its prociency in large part to the

efforts of its commanding ofcer.

53

Another forceful personality was Lt. Col. David Branson of the 62d USCI.

Branson took severe measures to promote literacy in his command. He ordered

that any soldier found playing cards would “be placed standing in some prominent

51

XXV Corps, GO 63, 28 Sep 1865, Entry 520, XXV Corps, General Orders, pt. 2, RG 393, NA.

52

Maj Gen H. G. Wright to Maj Gen G. Weitzel, 16 Nov 1865, Entry 2073, U.S. Forces on the

Rio Grande, LR; Maj Gen G. Weitzel to Col C. H. Whittlesey, 26 Nov 1865, Entry 2063, U.S. Forces

on the Rio Grande, LS; both in pt. 2, RG 393, NA.

53

Brig Gen J. P. Hawkins to Maj Gen G. Granger, 24 Jun 1865, 46th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94,

NA. For the Mound Plantation ght, see Chapter 6, above.

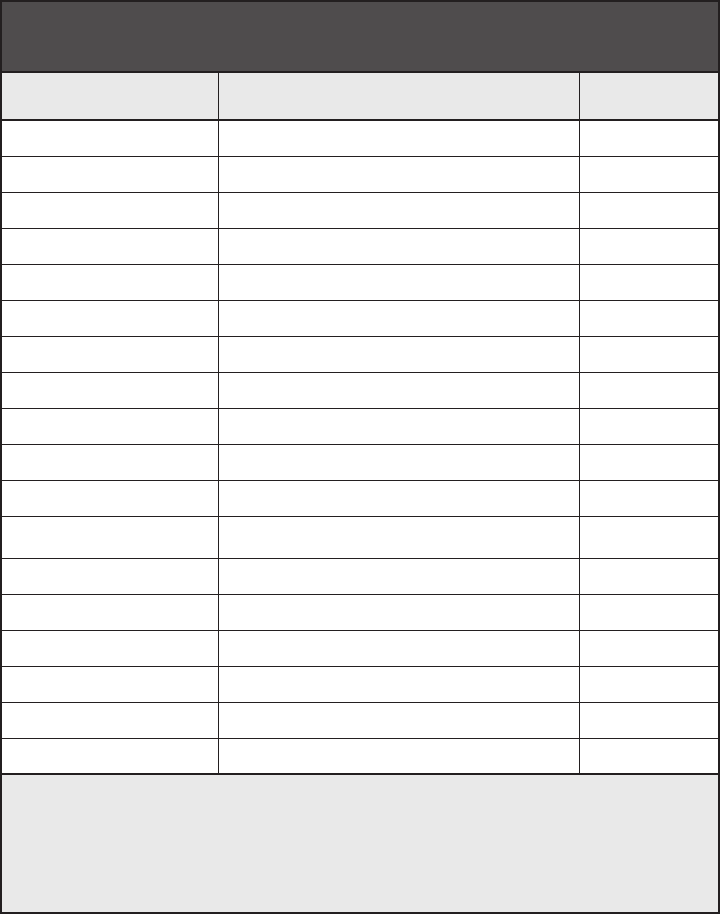

Table 4—General Weitzel’s Ranking of

Regiments in XXV Corps, November 1865

Regiment Mustered In No. Engagements

7th USCI September–November 1863 11

9th USCI November 1863 4

46th USCI May 1863 1

62d USCI December 1863 2

38th USCI January–March 1864 2

114th USCI July 1864 0

2d USCC December 1863 8

36th USCI October 1863 6

19th USCI December 1863–January 1864 3

10th USCI November 1863–September 1864 4

117th USCI July–September 1864 1

109th USCI July 1864 0

116th USCI June–July 1864 1

118th USCI October 1864 2

115th USCI July–October 1864 0

122d USCI December 1864 0

1st USCC December 1863 6

8th USCA October 1864 1

USCA = United States Colored Artillery; USCC = United States Colored Cavalry;

USCI = United States Colored Infantry.

Source: Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (New York: Thomas

Yoseloff, 1959 [1909]), and Ofcial Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States

Army, 8 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Adjutant General’s Ofce, 1867), vol. 8.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

446

position in the camp with book in hand, and required then and there to learn a con-

siderable lesson in reading and spelling; and if unwilling to learn, he will be com-

pelled by hunger to do so. . . . No freed slave who cannot read well has a right to

waste the time and opportunity . . . to t himself for the position of a free citizen.”

After January 1865, illiterate noncommissioned ofcers of the regiment faced re-

duction to the ranks. Branson also took measures to promote personal cleanli-

ness: “The dirtiest man in each Company shall be thoroughly washed. . . . Each

Company Commander will detail one Corporal and two men for this purpose. The

practice will be repeated as often as it may be thought necessary.” Few command-

ing ofcers, if any, imposed such a vigorous program of personal improvement on

their men.

54

Among the regiments on the low end of Weitzel’s list, the 122d USCI had suf-

fered since its inception from most of the ills that aficted black regiments. Late in

October 1864, its four hundred fty armed and equipped recruits had had only six

company ofcers (captains and lieutenants) present and t for duty. The situation

had barely improved by February, when the regiment was on the move to Virginia.

“Many of the ofcers have not yet reported,” Col. John H. Davidson complained.

“There is considerable sickness in the command, and . . . several of the companies

have but a single ofcer.” Arriving in Virginia, the individual companies found

themselves “scattered at various points, too remote from Head Quarters to receive

medical attendance from the Surgeon,” so sickness continued unabated. In the same

letter, Davidson asked that ofcers who had not yet reported have their appoint-

ments revoked and that others be named in their place. The regiment, he explained,

had never had more than half its full complement of thirty company ofcers.

55

With the possibility of instruction so limited, many of the men never learned to

care for their weapons. By the end of February 1865, 152 of the regiment’s Eneld

ries, some 20 percent, had been condemned as “unserviceable,” Colonel David-

son complained, “and each day adds to the number.” Furthermore, since compa-

nies of the regiment guarded lighthouses and other important sites miles from the

trenches around Richmond and Petersburg, “the Commissary of Subsistence only

issues the ration prescribed for troops in garrison duty, and the men really do not

get enough to eat.” Men and ofcers alike complained of the limited fare, and

Davidson asked that they receive the usual ration for troops in the eld. Finally,

although the regiment had begun organizing the previous October, a paymaster did

not visit it until the following March. “The . . . Ofcers are mostly men promoted

from the ranks and have performed the duties of Ofcers so long without pay, that

they are entirely destitute of funds to clothe themselves properly or meet their in-

cidental expenses,” Davidson wrote. The colonel’s neglect to mention any possible

inconvenience to the enlisted men suggests that ofcers’ attitudes were yet another

54

1st Missouri Inf (African Descent), GO 9, 11 Feb 1864 (“the dirtiest man”); 62d USCI, GO

31, 3 Jul 1864, and GO 35, 29 Oct 1864 (“be placed”); all in 62d USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94,

NA. Keith P. Wilson, Campres of Freedom: The Camp Life of Black Soldiers During the Civil War

(Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2002), pp. 82–108.

55

Lt Col D. M. Layman to Col J. S. Brisbin, 23 Oct 1864; Col J. H. Davidson to Adj Gen, Army

of the James, 1 Feb 1865 (“Many of”), and to Maj C. W. Foster, 15 Feb 1865 (“scattered at”); all in

122d USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

South Texas, 1864–1867

447

way, besides inadequate weapons and rations or infrequent paydays, in which the

122d USCI fell far short of bare adequacy.

56

The ability and character of a regiment’s ofcers was just as important for

training and discipline as the sheer number of ofcers present for duty—perhaps

more so. The longer service, on average, that was common to the top nine regi-

ments on Weitzel’s list meant that most of their ofcers had been appointed earlier

in the war and seemed to be of better quality than many of those who joined the

Kentucky infantry regiments (most of which received numbers between 107 and

125) during the autumn of 1864. While inept ofcers could be found in various

proportions in black regiments from all parts of the country, incidents of fraud and

theft seemed to occur mostly during the last months of the war and to concentrate

in the Kentucky regiments. These involved regimental ofcers of all grades. Es-

pecially odious was Col. William W. Woodward, of the 116th USCI, who diverted

$3,300 of his soldiers’ bank deposits to his own use during the regiment’s eight

months in Virginia and made off with more money in December 1865, when he

managed to leave the Army with an honorable discharge. Efforts to track down the

former colonel resulted only in a report, months later, that he was “leading a ‘sport-

ing’ life on a Mississippi Steamboat.” After consulting former ofcers and enlisted

men of the regiment, an investigator concluded that professional gambling was “an

occupation rendered probable by [Woodward’s] life while with the command.”

The lieutenant colonel of the 124th USCI, a regiment organized early in 1865 that

spent its entire ten-month service in Kentucky, received a sentence of three years’

imprisonment for embezzling $7,350 of his soldiers’ bounty money. Little wonder,

then, that seven Kentucky regiments were among the nine that made up the bottom

half of Weitzel’s list.

57

Department of Texas headquarters apparently paid serious attention to Weit-

zel’s advice, for when it issued the next order for mustering out regiments, six of

the eight named came from the bottom nine on the general’s list: the 1st USCC;

the 8th USCA; and the 109th, 115th, 118th, and 122d USCIs. Also on the list were

the 2d USCC, in accordance with the War Department’s practice of mustering out

cavalry and artillery regiments, which were more expensive to maintain than infan-

try, and the 46th USCI, the senior black regiment in Texas. The rst to be raised by

Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas in May 1863, the 46th had only eight months

56

Col J. H. Davidson to Lt Col E. W. Smith, 28 Feb 1865 (“unserviceable”); to Capt S. L.

McHenry, 3 Mar 1865 (“the Commissary”); to Brig Gen B. W. Brice, 9 Mar 1865 (“The . . .

Ofcers”); all in 122d USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

57

A. M. Sperry to J. W. Alvord, 18 Dec 1866, NA Microlm Pub M803, Rcds of the Education

Div of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, roll 14; Endorsement, Lt Col D.

H. McPhail, 18 Feb 1867 (quotation), on S–53–DG–1867, Entry 1756, Dept of the Gulf, LR, pt. 1,

RG 393, NA. The les of the Freedmen and Southern Society Project at the University of Maryland,

which contain photocopied material from the National Archives, include at least seven instances of

ofcers suspected of, and even tried for, defrauding enlisted men. All but one of them occurred in

Kentucky regiments: the 12th USCA (le G44), 109th USCI (B214), 114th USCI (B318), 117th USCI

(CC14), 123d USCI (G178), and 124th USCI (H19). Problems of ofcer replacement at the end of

a long war were not unique to the Union Army. For a British reminiscence of the First World War,

see Robert Graves, Good-Bye to All That: An Autobiography (London: Jonathan Cape, 1929), pp.

304–05. For the U.S. Army in the Second World War, see Jeffrey J. Clarke and Robert R. Smith,

Riviera to the Rhine, U.S. Army in World War II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military

History, 1993), p. 569.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

448

of its three-year term left to serve. The departure of these regiments left only ten

in the entire XXV Corps, with a strength of fewer than ve thousand ofcers and

men present for duty.

58

With barely enough black regiments in southern Texas to constitute one di-

vision, General Sheridan recommended the discontinuance of the XXV Corps.

Communications were so difcult in Texas, he told Grant, that a regional chain

of command allowing post commanders to report directly to district headquarters

rather than through the hierarchy of brigade, division, and corps, would move mes-

sages more quickly. Grant agreed to the proposal, and the XXV Corps ceased to

exist on 8 January 1866.

59

While more than half of the regiments in the corps were mustering out, the

conict across the Rio Grande that was the cause of their presence wore on. In

the late winter of 1865, the Imperialists dominated all of Mexico except for four

states on the Pacic coast and the northern border, but by the following winter the

tide had turned. Inuenced by the collapse of the Confederacy and the presence of

more than forty-ve thousand United States troops in Texas, by the Imperialists’

inability to subdue the Liberals and impose order on the country, and by wor-

ries about his increasingly bellicose neighbor Prussia, Napoleon III announced on

15 January 1866 his intention to withdraw by October 1867 the thirty thousand

French troops that were the most reliable support of the Imperialist regime.

60

“About ninety eight out of every hundred ofcers and men are strongly in favor

of the Liberals,” General Weitzel told department headquarters in early January 1866.

For many United States citizens in the region, commercial interests outweighed alle-

giance to one side or another in a foreign country’s politics, but some Americans saw

opportunities to be gained by favoring the Liberals. Two of these were R. Clay Craw-

ford and Arthur F. Reed, adventurers who had gravitated to the Rio Grande after the

war. Crawford was an honorably discharged former captain in the Union Army who

claimed to hold a major general’s commission in the Liberal forces. Reed was a for-

mer lieutenant colonel of the 40th USCI. A general court-martial had cashiered him

in June 1865 for neglect of duty, insubordination, insulting his commanding ofcer,

absence without leave, breaking arrest, and “utter incompetence for military com-

mand.” To be cashiered meant ineligibility for further military ofce in the United

States. Reed claimed to be a colonel in the Liberal forces.

61

Matamoros had been in the hands of the Imperialists since September 1864. In

the fall of 1865, its garrison withstood a sixteen-day siege by the Liberals. Suffer-

ing more than ve hundred casualties in their attempt to take the city, the Liberals

58

Dept of Texas, SO 8, 9 Jan 1866, Entry 2073, and Trimonthly Inspection Rpt, 31 Oct 1865,

Entry 539, both in pt. 2, RG 393, NA. On the muster-out policy, see War Department, GO 144, 9 Oct

1865, which authorized muster-out of all volunteer cavalry regiments east of the Mississippi River.

Entry 44, Orders and Circulars, RG 94, NA.

59

Maj Gen P. H. Sheridan to Lt Gen U. S. Grant, 30 Dec 1865 (G–1056–AGO–1865), NA

Microlm Pub M619, AGO, LR, 1861–1870, roll 360.

60

Krause, Mexico, pp. 177–86; Vanderwood, “Betterment for Whom?” pp. 386–91; James E.

Sefton, The United States Army and Reconstruction, 1865–1877 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 1967), p. 261.

61

Maj Gen G. Weitzel to Maj Gen H. G. Wright, 7 Jan 1866, led with (f/w) Maj Gen H. G.

Wright to Col G. L. Hartsuff, 14 Jan 1866, Entry 4495, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Case of A. F. Reed

(OO–1302), Entry 15, RG 153, NA.

South Texas, 1864–1867

449

withdrew and contented themselves during the weeks that followed with harassing

river trafc and ambushing small detachments of Imperialists. Late in December,

Crawford and Reed made plans with the Liberal leader Mariano Escobedo to seize

the port of Bagdad. Crawford was sure that this would force the Imperialists out

of Matamoros.

62

Across the Rio Grande from Bagdad, the camp of the 118th USCI stood near

the town of Clarksville. Some time between 3:00 and 4:00 a.m. on 5 January

1866, the regiment’s commanding ofcer awoke to the sound of cannon re from

a French gunboat on the river. Enlisted men on guard speculated that “the French

were ghting among themselves.” Reed, with a force estimated at between sixty

and one hundred fty men, had taken Bagdad. The Imperialist garrison surren-

dered quickly, many of the men changing sides on the spot. Among Reed’s force

were about thirty men of the 118th USCI.

63

The gunre also alerted 1st Lt. Joseph J. Fierbaugh, the ofcer of the day,

stationed on a steamer moored at the Clarksville landing. He sent part of the guard

to arrest any returning absent soldiers and to stop any more from crossing. About

6:00, an hour before rst light, Fierbaugh himself crossed the river to Bagdad.

Since he did not have a sufcient force to return men to camp under an armed

guard, he merely sent those he found to the riverbank, where a small boat took

62

R. C. Crawford to M. Escobedo, 23 Dec 1865 (f/w A–909–AGO–1866), and A. F. Reed to R.

C. Crawford, 28 Dec 1865, both in NA M619, roll 452; Thompson, Cortina, pp. 147, 162–66.

63

“Proceedings of a Military Commission,” f/w A–909–AGO–1866, and Lt Col I. D. Davis to

Col R. M. Hall, 5 Jan 1866, both in NA M619, roll 452.

Palm trees and the twin spires of a Roman Catholic church gave Frank Leslie’s readers

a sense of the foreignness of the Mexican port of Matamoros, across the Rio Grande

from Brownsville.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

450

them across. Most returned to camp in time to answer reveille roll call. Two who

did not were Cpl. William Oates and Pvt. Dade Davis, who were among the four

killed on the Liberal side during the night’s ghting.

64

When Surgeon Russell D. Adams went to Bagdad later that morning, he found

another soldier of the regiment lying wounded but did not bother to learn his name.

This seems to have been typical of the ofcers of the 118th USCI. Fierbaugh was

unable to name any of the soldiers he rounded up in Bagdad. Capt. Lewis Moon,

who succeeded him as ofcer of the day, told a military commission that he did not

know the name of any soldier outside his own company. Moreover, both Fierbaugh

and Moon told the commission that the regiment had never kept a record of which

of its soldiers were arrested or of how they were punished. Since Moon had no

specic instructions to record the names of men he arrested, he did not feel obliged

to do so. Evidently, the 118th USCI had not improved during the two months since

it had ranked fth from the bottom on General Weitzel’s list.

65

By daybreak, refugees from the ghting packed both banks of the river, with

boats plying back and forth to carry them across. When Surgeon Adams visited

Bagdad later that morning to care for the wounded, he found “considerable com-

motion around town,” with soldiers “running around the streets. . . . [E]verything

seemed to be in confusion.” Mexican authorities soon saw that they were unable

to restore order and asked the commanding ofcer at Clarksville for assistance.

The next day, two hundred ofcers and men of the 118th USCI crossed the river

to occupy Bagdad. A force from the 46th USCI, a regiment that General Weitzel

considered much more reliable, replaced them within a few days.

66

On 17 January, one hundred fty ofcers and men of the 2d USCC arrived at

Bagdad to relieve the 46th; the rest of the cavalry, some three hundred strong, re-

mained on the opposite bank. A Liberal general assured the commanding ofcer of

the 2d USCC that he was not yet able to guarantee order in the town. The cavalry

stayed on, patrolling the streets while Liberal troops manned defenses around the

outskirts, for another ve days until an order recalled them to Brazos Santiago. On

25 January, an attack by a mixed force of more than ve hundred Austrian, French,

and Mexican troops drove the Liberals from Bagdad and the Imperialists regained

a tenuous control of the south bank of the Rio Grande.

67

Affairs on the Mexican side of the river remained turbulent for the next ve

months, with the Imperialists holding the major towns. A New Orleans newspaper

summed up the situation ippantly, naming several local generals and would-be

generals: “Canales outlaws Cortina, Escobedo & Co. outlaws both, and Mejía out-

laws the whole gang.” Sheridan took a more serious tone in a letter to Grant: “The

Liberals are in good spirit, and are doing very well. They are divided in Tamau-

lipas, and there waste their strength, but all are contending against the common

enemy.” In mid-June, a Liberal force attacked an Imperialist supply train, killing

or capturing nearly all of the train’s 1,400-man escort. Within a week, the Imperial-

64

“Proceedings of a Military Commission”; Descriptive Book, 118th USCI, Regimental Books,

RG 94, NA.

65

“Proceedings of a Military Commission.”

66

Ibid.; F. de Leon to Lt Col I. D. Davis, 5 Jan 1866; Col J. C. Moon to Col D. D. Wheeler, 6 Jan

1866; Lt Col F. J. White to Capt W. D. Munson, 22 Jan 1866; all in NA M619, roll 452.

67

White to Munson, 22 Jan 1866; Thompson, Cortina, p. 169.