Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

471

ana listed twelve ofcers from four black regiments in his division who were

absent, lling positions that ranged from acting mayor of New Orleans to post

quartermaster at Jackson, Mississippi.

32

In the spring of 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau itself had to be staffed. Al-

though one early call for Louisiana eld agents requested four ofcers from

black regiments and four from white, the constant mustering out of white

volunteers that summer shifted the burden of providing agents increasingly

to ofcers of the U.S. Colored Troops. When the assistant commissioner for

Mississippi sent General Howard his roster of Bureau ofcers in mid-August,

thirty-nine of his forty-eight headquarters staff and eld agents came from ten

of the black regiments stationed in the state. Elsewhere, the same situation pre-

vailed. At Alexandria, Louisiana, the 80th USCI had only six ofcers on duty

with the regiment’s ten companies. At Nashville, Tennessee, command of the

101st USCI fell to a captain who had to report that only eight of the regiment’s

ofcers were present while fteen were on detached service. The general com-

manding at Jackson, Mississippi, complained that “in some instances, by no

means rare, subaltern ofcers have to take charge of two companies, in one

instance of three.”

33

Since the cost of horses, tack, and fodder made cavalry expensive to main-

tain, the adjutant general issued an order during the rst week of May 1865,

just days after the surrender of Confederate armies between the Appalachians

and the Mississippi River, for the muster-out of all volunteer cavalry troopers

whose enlistments would expire in the next four months. The remaining men

would reorganize as full-strength regiments. Ofcers and noncommissioned

ofcers declared surplus by local commanders were also to muster out. The

order did not affect the black cavalry regiments, in which the men’s three-year

enlistments would not begin to run out until late 1866, but it reduced drasti-

cally the size of the mounted force available to patrol the occupied South. Only

eight days after the order, the colonel of the 49th USCI wrote from Jackson,

Mississippi, that “there ought to be at least two hundred well mounted Cavalry

at this Post for the purpose of protecting the inhabitants from . . . the ‘Bush-

whackers’ who are very numerous in this vicinity.” At the beginning of June,

the general commanding at Jacksonville, Florida, made a similar request.

34

Dwindling troop strength detracted from the efcacy of the occupying

force. The Southern District of Mississippi, headquartered at Natchez, pub-

lished a list of posts and their garrisons at the beginning of September. In the

32

Lt Col J. M. Wilson to Lt Col C. T. Christensen, 12 Jun 1865 (I–81–DG–1865), and Brig Gen

J. P. Hawkins to Lt Col C. T. Christensen, 15 Jun 1865 (H–193–DG–1865), both in Entry 1756, Dept

of the Gulf, LR, pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

33

T. W. Conway to Lt Col C. T. Christensen, 15 Jun 1865 (C–360–DG–1865), Entry 1756; Lt

Col A. W. Webber to Brig Gen L. Thomas, 22 Aug 1865 (W–147–DL–1865), Entry 1757; Maj Gen

P. J. Osterhaus to Capt J. W. Miller, 15 Aug 1865 (M–359–DM–1865), Entry 2433; all in pt. 1, RG

393, NA. Col S. Thomas to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 15 Aug 1865 (T–123), NA M752, roll 18; Roster

of Ofcrs, 101st USCI, 10 Sep 1865 (R–76), NA T142, roll 27.

34

Col V. E. Young to Maj Gen G. K. Warren, 16 May 1865 (Y–B–27–DM–1865) (“there

ought”), Entry 2433, RG 393, NA; Brig Gen I. Vogdes to Maj W. L. M. Burger, 4 Jun 1865 (V–40–

DS–1865), Entry 4109; both in pt. 1, RG 393, NA. Orders disbanding volunteer cavalry and horse-

drawn artillery between May and Oct 1865 are in OR, ser. 3, 5: 11–12, 48–49, 94–97, 516–17.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

472

eighteen counties that constituted the district, 4,110 ofcers and men were

responsible for policing more than fteen thousand square miles. Less than

one-third of the district was farmland, concentrated at the western edge of the

state in the rich alluvial soil of the plantation country along the Mississippi

River. The rest of the district consisted of sandy soil and pine forest that ex-

tended east through the Florida panhandle, the same forest that Brig. Gen. John

P. Hawkins’ division of Colored Troops had marched through earlier that year

on its way from Pensacola to the siege of Mobile. The thick piney woods of

the region were inviting to those eeing from authority and difcult for pursu-

ers to penetrate. In the southern district, only 359 soldiers were mounted, and

they were scattered at ve posts that ranged in size from 149 troopers at Port

Gibson to 12 at Fayette. They belonged to a white regiment from New Jersey

that mustered out on 1 November, leaving the district with no trained cavalry.

All a local commander could do was to mount his infantry on horses or mules

that belonged to the quartermaster and hope for the best.

35

Throughout the summer, as the War Department continued to disband vol-

unteer mounted regiments, pleas for cavalry reached state headquarters of the

Army and the Freedmen’s Bureau. An inspector in South Carolina reported that

infantry troops on duty in the state “show a very creditable efciency but they

frequently have to march long distances to quell disturbances and often arrive

too late to do good. A small force of cavalry would be of innite service.” A

captain of the 6th USCA, serving as Bureau agent at Woodville, Mississippi,

welcomed the arrival of some cavalry. “I got along quietly without them,” he

told the assistant commissioner, “but I could not do much business.” At Mis-

sissippi City, a major of the 66th USCI sent “a scout” of mounted infantry

to arrest a gang of returned Confederates who were murdering and abusing

freedpeople; the Bureau agent, another ofcer of the regiment, recommended

assignment of “a small squad of Cavalry” to the post. In Arkansas, “many acts

of brutality are perpetrated upon the unfortunate and unprotected negroes,” a

captain of the 83d USCI reported. As a Bureau agent, he added that the white

population in the southwestern part of the state was “most bitter, and hostile

in the extreme, nothing deters them from . . . the foulest crimes, but the dread

of our soldiers, for whom they entertain feelings of ‘holy horror.’ . . . The im-

portance of . . . small forces of Cavalry can not be fully realized until one has

had to do with these half whiped barbarians.” The recommendations of agents

did not matter. By September, the inexorable process of mustering out left only

one mounted regiment in all of Arkansas. Throughout the fall, the War Depart-

ment continued to muster out volunteer cavalry regiments across the South. Of

thirteen mounted regiments serving in North Carolina during April, all were

35

Station List of Troops, 1 Sep 1865, NA M1907, roll 33; U.S. Census Bureau, Agriculture of

the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Ofce, 1864), p. 84; William

Thorndike and William Dollarhide, Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790–1920 (Baltimore:

Genealogical Publishing, 1987), p. 187; Rand McNally Commercial Atlas and Marketing Guide,

2008, 2 vols. (Chicago: Rand McNally, 2008), 2: 147. For instances of local commanders raising

companies of mounted infantry, see Osterhaus to Miller, 19 Aug 1865; Brig Gen C. H. Morgan to

Capt C. E. Howe, 16 Sep 1865 (M–129 [Sup] DA–1865), Entry 269, pt. 1, RG 393, NA. On the march

of General Hawkins’ division, see Chapter 5, above.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

473

gone by the end of October; of eleven at Vicksburg and other posts on the lower

Mississippi River, only one remained by December.

36

Meanwhile, the War Department further accelerated the disbandment of vol-

unteers by ordering the muster-out of all black regiments raised in Northern

states. The order went out on 8 September. By mid-December, men from thirteen

regiments at garrisons in Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, the Carolinas, and Vir-

ginia had returned home. Besides eleven regiments that mustered out in Texas,

those affected by the order were the 11th USCA (Rhode Island); the 1st USCI

(Washington, D.C.); the 3d, 6th, 24th, and 25th USCIs (Pennsylvania); the 5th

and 27th USCIs (Ohio); the 20th USCI (New York); the 60th USCI (Iowa); the

79th and 83d USCIs (Kansas); and the 102d USCI (Michigan). Mustering out

had begun even earlier in South Carolina, with the 26th USCI (New York), the

32d USCI (Pennsylvania), and the 54th and 55th Massachusetts leaving by the

end of August.

37

The impetus for disbanding these troops was certainly not electoral, for while

tens of thousands of voters in the Union’s main eld armies had received their

discharges in the summer of 1865, black men could not vote in most Northern

states. Rather, the reason may have been complaints about black soldiers from

the provisional governors of Southern states, the president’s own appointees. On

10 August, the governor of South Carolina reported “dissatisfaction” among the

white population “on account of colored troops garrisoning the country villages

& town. . . . [T]he black troops are a great nuisance & do much mischief among

the Freed men.” He followed this complaint with another two weeks later. The

same month also saw the arrival of similar letters from the governors of Missis-

sippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee. By the end of the year, a total of fty black

regiments had mustered out, consolidated, or otherwise left the Army (Table 5).

38

An incident at Hazlehurst, Mississippi, in October showed the recalcitrance

of those Southern whites whom the Arkansas agent had called “half whiped

barbarians.” The town had sprung up a few years before the war when a railroad

from New Orleans to Jackson bypassed Gallatin, the seat of Copiah County. Since

then, Hazlehurst had prospered. It stood some thirty-ve miles south of Jackson

and about twice that distance east of Natchez, headquarters of the military Southern

36

Capt H. S. Hawkins to 1st Lt J. W. Clous, 13 Aug 1865 (“show a very”), NA M869, roll 34;

Capt W. L. Cadle to Maj G. D. Reynolds, 31 Aug 1865 (“I got”), NA M1907, roll 34; Capt J. R.

Montgomery, quoted in Maj W. G. Sargent, 31 Aug 1865 (“most bitter”), NA M979, roll 23. OR, ser.

1, vol. 48, pt. 2, pp. 265–67, lists cavalry regiments in Arkansas on 30 April 1865; cavalry regiments

in the Department of the Gulf are on pp. 256, 260; in North Carolina, vol. 47, pt. 1, p. 55. Muster-

out dates are in Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (New York: Thomas

Yoseloff, 1959 [1908]), pp. 113, 118–19, 127–28, 131, 141, 144, 146, 150, 165–66, 177, 180, 200, 215,

230, 237. For the extent of Northern demobilization, see Mark R. Wilson, The Business of Civil War:

Military Mobilization and the State, 1861–1865 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006),

pp. 191–95, 202–03.

37

The text of the War Department order is in OR, ser. 3, 5: 108. Dyer, Compendium, pp. 1266,

1728–29.

38

Letters from the governor of South Carolina to Andrew Johnson are in Johnson Papers, 8:

558 (quotation), 651; complaints from other governors are on pp. 556, 653, 666–68, 686. On white

Southerners’ abhorrence of black soldiers, see Chad L. Williams, “Symbols of Freedom and Defeat:

African American Soldiers, White Southerners, and the Christmas Insurrection Scare of 1865,” in

Black Flag over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War, ed. Gregory J. W. Urwin

(Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), pp. 210–30, esp. pp. 213–17.

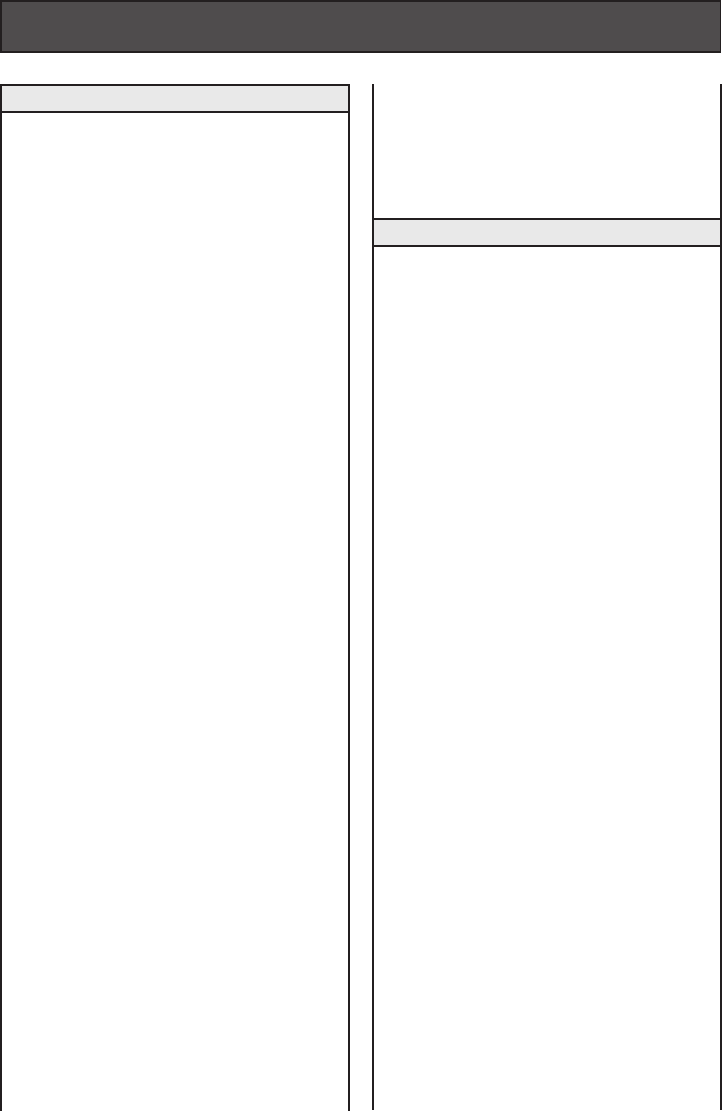

1865

20 Aug 54th Mass Infantry

22

32d USCI

28 26th USCI

29 55th Mass Infantry

20 Sep 5th and 6th USCIs

21 27th USCI

27 73d USCI

29 1st USCI

30 102d USCI

1 Oct 24th and 79th USCIs

2 11th USCA

7 20th USCI

9 83d USCI

11 74th USCI

15 60th USCI

16 22d and 123d USCIs

20 43d and 127th USCIs

23 135th USCI

24 124th USCI

29th Conn Infantry

31 5th Mass Cavalry

3d USCI

4 Nov 45th USCI

6 29th USCI

7 31st USCI

8 28th USCI

10 8th USCI

18 13th USCA

25 75th USCI

30 23d USCI

4 Dec 39th USCI

6 25th USCI

10 30th and 41st USCIs

11 14th USCA

26 100th USCI

30 61st USCI

31 55th, 76th, and 92d USCIs

1866

4 Jan 48th and 136th USCIs

5 2d and 47th USCIs

6 78th and 138th USCIs

9 63d USCI

10 13th USCI

12 11th USCI

15 137th USCI

16 12th USCI

21 101st USCI

26 3d USCC

29 96th USCI

30 46th USCI

31 33d, 42d, and 59th USCIs

4 Feb 1st USCC

5 68th and 104th USCIs

6 109th, 110th, and 118th USCIs

8 122d USCI

10 8th USCA, 115th USCI

12 2d USCC

21 18th USCI

25 4th USCA

28 34th USCI

7 Mar 70th USCI

8 53d USCI

13 64th USCI

14 84th USCI

16 5th USCC

20 4th USCC; 50th and 66th USCIs

21 108th USCI

22 49th USCI

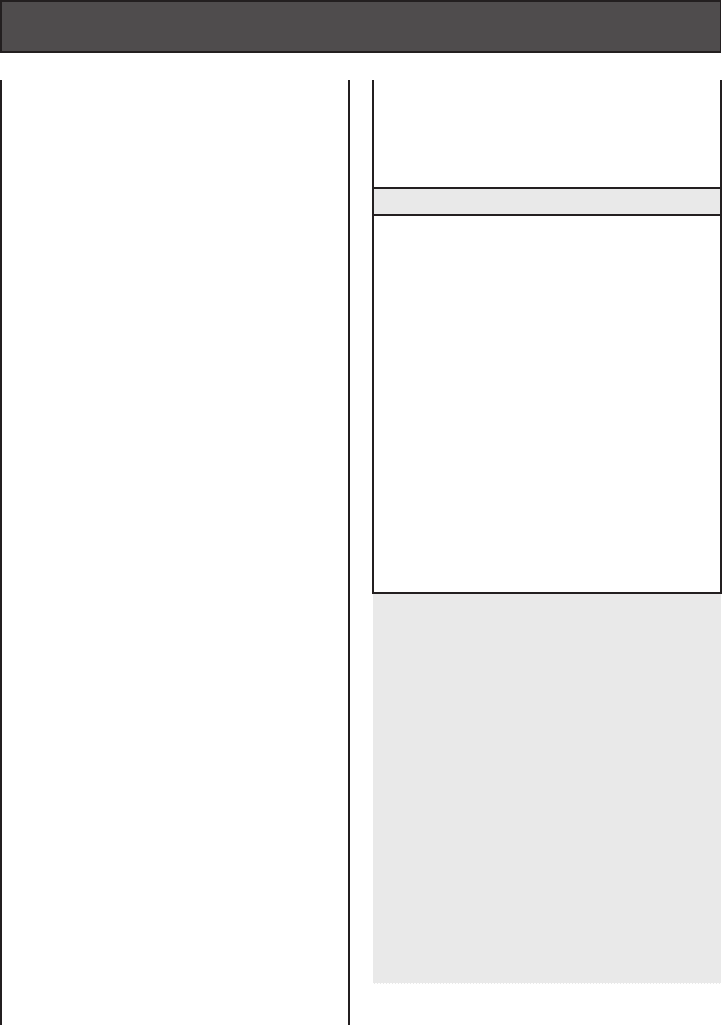

Table 5—Muster-out Dates of Black Regiments

26 14th USCI

31 1st USCA, 62d USCI

2 Apr 114th USCI

6 97th USCI

7 15th USCI

9 113th USCI

10 86th USCI

15 6th USCC

15–20 103d USCI

23 99th USCI

24 12th USCA

25 17th, 21st, and 40th USCIs

27 119th USCI

30 3d USCA; 16th, 44th,

58th, and 111th USCIs

4 May 4th USCI

5 52d USCI

13 6th USCA

17 10th USCI

20 5th USCA

1 Jun 35th USCI

16 51st USCI

10 Sep 82d USCI

15 56th USCI

10 Oct 128th USCI

13 7th USCI

28 36th USCI

22 Nov 107th USCI

26 9th USCI

30 81st USCI

13 Dec 57th USCI

1867

8 Jan 65th USCI

15 19th USCI

17 116th USCI

25 38th USCI

11 Feb 37th USCI

22 10th USCA

1 Mar 80th USCI

10 Aug 117th USCI

20 Dec 125th USCI

USCA = United States Colored Artillery;

USCC = United States Colored Cavalry; USCI

= United States Colored Infantry.

Notes: The 54th USCI “mustered out

of service by companies at different dates

from August 8 to December 31, 1866.” Of-

cial Army Register of the Volunteer Force of

the United States Army, 8 vols. (Washington,

D.C.: Adjutant General’s Ofce, 1868), 8:

227 (hereafter cited as ORVF). The 2d USCI

batteries mustered out as follows: A, 13 Janu-

ary 1866; B, 17 March 1866; C, D, and F, 28

December 1865; E, 26 September 1865; G,

12 August 1865; H, 15 September 1865; I, 10

January 1866; Independent Battery, 22 July

1865. ORVF, 8: 165–68.

Table 5—Muster-out Dates of Black Regiments—Continued

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

476

District of Mississippi. The 1860 census had counted 7,432 whites; 7,963 slaves;

and one free black man living in the county.

39

In the fall of 1865, Hazlehurst was the site of a Freedmen’s Bureau ofce. The

agent was Capt. Warren Peck of the 58th USCI, a regiment that had been raised

at Natchez two years earlier. Regimental headquarters was at Brookhaven, twenty

miles to the south; one company garrisoned Hazlehurst, partly to help Captain

Peck in his work and partly to guard cotton gathered there from the surround-

ing country. In Mississippi, the Confederate government had owned more than

127,000 bales of cotton, worth nearly $8 million. When the ghting ceased, U.S.

Treasury agents began impounding what they could nd of it while private citizens

and government ofcials, civilian and uniformed, stole what they could. At Nat-

chez, Major Reynolds complained of “high-handed and extensive cotton thefts”

throughout the country, engineered by “white men, who employ negroes to steal

for them. The large scale on which their operations are conducted shows that it is

an organized affair.”

40

Crime in Mississippi went largely unchecked that summer as the state endured

a tug-of-war between its civilian governor and the military authorities. In June,

President Johnson had appointed William L. Sharkey, a Mississippi politician who

had opposed secession in 1860, as provisional governor of the state. Two months

later, while the reconstruction convention debated reform of the state constitution,

Sharkey asked the president to repeal martial law. He had recently issued a call to

raise companies of militia in each county, ostensibly “to suppress crime, which is

becoming alarming,” he told Johnson.

41

When General Osterhaus, at Jackson, saw a newspaper advertisement that

urged the formation of a local militia company, he wrote to the provisional gov-

ernor, reminding him that the state was still under martial law “and that no mili-

tary organizations can be tolerated which are not under control of United States

ofcers.” The same day, the general told department headquarters that Sharkey

had mentioned in conversation that the main purpose of the militia was “to sup-

press any acts of violence, which the negroes may attempt to commit during

next winter.” Osterhaus had retorted, he went on, that all the violent criminals

awaiting trial in the state were white, “young men . . . lately returned from mili-

tary service, just the very same men, who in all probability would join the . . .

companies of militia. The result of the organization of such companies, while

the state is occupied by U.S. troops, mostly colored, cannot be doubted.” After

ten days of correspondence between the governor, department headquarters, and

Washington, the president decided to support Sharkey in organizing state militia.

Col. Samuel Thomas, the Freedmen’s Bureau assistant commissioner for Mis-

sissippi, thought that a transfer of authority from federal to state ofcials could

not “be smoothly managed in the present temper of Mississippi. . . . [W]e are in

39

U.S. Census Bureau, Population of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.: Government

Printing Ofce, 1864), p. 270.

40

Station List of Troops, 1 Sep 1865, NA M1907, roll 33; Lt Col N. S. Gilson to Maj Gen P.

J. Osterhaus, 16 Nov 1865, and Afdavits, Sgt William Gray, n.d., and Pvt Lewis Donnell, 31 Oct

1865, all in Warren Peck le (P–84–CT–1863), Entry 360, Colored Troops Div, LR, RG 94, NA;

Reynolds to Eldridge, 31 Aug 1865; Harris, Presidential Reconstruction, pp. 63–68.

41

Johnson Papers, 8: 628 (quotation); Harris, Presidential Reconstruction, pp. 72–73.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

477

honor bound to secure to the helpless people we have liberated a republican form

of government, and . . . we betray our trust when we hand these freedmen over

to their old masters.”

42

This was the uneasy state of affairs in Mississippi on the morning of 13 Oc-

tober, when a white resident of Copiah County entered the Hazlehurst Freed-

men’s Bureau ofce “in a boisterous and deant manner,” as Captain Peck later

testied. Drury J. Brown, a planter who had led a regiment of Confederate

infantry during the war, accused Peck of extorting money under the pretense of

collecting a tax from employers of freedmen. Brown then left but returned in

the afternoon and became quarrelsome and abusive. When he shoved Peck, the

captain called a private of the 58th USCI into his ofce and ordered Brown’s

arrest. The planter was drunk, “which I did not notice until he refused to re-

spect the arrest,” Peck said. It took three soldiers to drag Brown out of the

ofce. “We took hold of Mr. Brown and with considerable struggling . . . got

him out of the back door,” Sgt. William Gray testied. They dragged Brown by

his legs to the veranda of a nearby house that served the Freedmen’s Bureau

as a jail, “not having any more appropriate place,” Peck explained. Within an

hour, the captain released his prisoner on the understanding that Brown would

go home.

43

The next day, Peck took a train some seventy-ve miles to department head-

quarters at Vicksburg, where he hoped to collect copies of some recent orders that

had not reached Hazlehurst. Returning on 18 October, he found the infantry com-

pany withdrawn to regimental headquarters at Brookhaven, leaving a sergeant and

six privates to keep watch over impounded cotton. On the same day, Drury Brown

took his complaint of being manhandled by black soldiers to a justice of the peace,

who issued an order to the sheriff for Peck’s arrest. About half an hour after the

captain reached Hazlehurst, a deputy tried to serve the warrant on him, but he re-

fused to acknowledge the right of the county to interfere with a federal ofcial in

the execution of his duties.

44

That evening, Pvt. Lewis Dowell stood guard over the cotton that was piled

near the railroad tracks. He heard a group of men pass by; one of them said, “He

thinks he cannot be taken because he has got a few Yankee niggers with him.”

About nine, Dowell heard Peck call for the guard. Sgt. Dilman George brought

the six privates at the double and found the captain some distance from his ofce,

surrounded by fteen or twenty men. Dowell counted four shotguns or revolvers

trained on Peck and six pointed toward the advancing soldiers. Three or four dozen

more men, most of them armed, stood “scattered down the road . . . in a sort of

scrmish line [sic],” Dowell remembered. As the rst of the soldiers came within

ten paces of the group, the sheriff cocked both hammers of his shotgun and ordered

42

Maj Gen P. J. Osterhaus to W. L. Sharkey, 21 Aug 1865, and Maj Gen P. J. Osterhaus to

Capt J. W. Miller, 21 Aug 1865 (M–347–DM–1865), both in Entry 2433, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Col

S. Thomas to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 21 Sep 1865 (M–5), NA M752, roll 22; Harris, Presidential

Reconstruction, pp. 73–74.

43

Afdavits, Capt W. Peck, 1 Nov 1865, and Gray, n.d., in Peck le.

44

Capt W. Peck to Maj G. D. Reynolds, 31 Oct 1865, NA M1907, roll 34. Afdavits, Dowell, 31

Oct 1865, and Peck, 1 Nov 1865; T. Jones to Sheriff, 18 Oct 1865, Peck le.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

478

him to stop, “or I will blow your brains out you black son of a bitch.” The soldiers

nally halted about ten yards from Peck, the sheriff, and the posse.

45

“We did not look behind us to see . . . whither there were any men or not,” Dowell

testied. “We had our guns levelled—each man of us had his man picked out in the

crowd.” Dowell aimed at the sheriff. While Peck talked to his captors, one of them

used his shoulder as a rest for the barrel of a shotgun pointed at the soldiers. After a

few minutes’ conversation that Peck’s men could not overhear, the captain agreed to

submit to arrest. As the posse and its prisoner left Hazlehurst, Pvt. Peter Williams fol-

lowed them for a while to learn whether the sheriff’s men intended to murder Peck.

Instead, they took him to Gallatin, the decaying county seat some four miles west of

the railroad, where Justice Thomas Jones held court. Required to post a $2,000 bond,

Peck refused to acknowledge the authority of county ofcials. When he declined to

post bond, they “locked [him] up in an iron cage in a very lthy room,” Peck testied.

“I was left in the cage from the 19th until the 23d Oct after which I was allowed to

walk about the room in the day time—and locked up in the cage during the night.”

46

How word of Peck’s arrest got out is not clear. He sent a note to his clerk in

Hazlehurst before entering the Gallatin jail, but the Bureau assistant commissioner

at Vicksburg got the news in a telegram from an Army staff ofcer at Jackson on

22 October. Then began ve days of correspondence between Colonel Thomas, the

assistant commissioner; General Osterhaus, commanding the Southern District;

Provisional Governor Sharkey; and the new popularly elected governor, Benja-

min G. Humphreys. When Humphreys asserted nally that any attempt by the ex-

ecutive (himself) to inuence a judicial proceeding (Peck’s arrest and trial) would

be unconstitutional, the general acted, ordering four companies of the 58th USCI

from Brookhaven to secure the captain’s release. To lead the expedition, Osterhaus

sent his judge advocate general, Maj. Norman S. Gilson of the 58th USCI.

47

At the same time Gilson released Peck, he arrested Judge Jones and Leonard

H. Redus, the deputy sheriff who had taken Peck from Hazlehurst to Gallatin.

Present at the arrests was another Freedmen’s Bureau agent, Capt. James T. Organ

of the 6th USCA. “When the said Redus was arrested and placed under guard, he

grew violent,” Organ testied, “saying that he had arrested Captain Peck and By

God if he had the power, he would get out a posse that night to arrest [Gilson]

and his whole party. . . . The father of the aforesaid Redus who was arrested at the

same time and place used very insulting and treasonable language saying I always

have been a Rebel and I am Rebel now.” How long Gilson held the justice and the

deputy is not clear.

48

Peck returned to Hazlehurst to nd that his ofce had been ransacked. He

blamed the entire affair on public opinion in Mississippi, which held that the fed-

eral government would withdraw its troops after the state elections, “that all au-

45

Afdavits, Dowell, 31 Oct 1865, Sgt D. George, 31 Oct 1865, and Peck, 1 Nov 1865, Peck le.

46

Ibid.

47

Lt Col R. S. Donaldson to Col S. Thomas, 21 Oct 1865 (D–56), NA Microlm Pub M826,

Rcds of the Asst Commissioner for the State of Mississippi, BRFAL, roll 9; Col S. Thomas to Maj

Gen O. O. Howard, 31 Oct 1865 (M–61), and B. G. Humphreys to Lt Col R. S. Donaldson, 23 Oct

1865, both in NA M752, roll 22; Maj N. S. Gilson to Maj Gen P. J. Osterhaus, 4 Nov 1865, and Maj

Gen P. J. Osterhaus to Maj Gen E. D. Townsend, 6 Nov 1865, both in Peck le.

48

Afdavits, Peck, 1 Nov 1865, and Capt J. T. Organ, 31 Oct 1865, Peck le.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

479

thority had been taken from the Freedmen’s Bureau, and that the Ofcers of the

Bureau were subject to trial before civil courts for their actions in any case where

they were not in accordance with the Code of Miss[issippi].” Osterhaus’ action did

much to correct that impression, and General Howard conrmed it later in the year

when he told Colonel Thomas:

Use all the power of the Bureau, to see that the Freedmen are protected . . . ,

and to that end . . . make application to the Dept. Commander, for such military

force to assist you, as you may deem necessary; the whole power of the Govern-

ment being pledged to sustain the actual freedom of the negro. . . . [W]henever

[state] authorities show a disposition to infringe upon any of [the freedmen’s]

rights, . . . or refuse them equal justice with other citizens, then you will take

such measures as may seem best to guard and protect their interests.

49

Captain Peck’s arrest had occurred without gunre, but indignant white South-

erners took many shots at their occupiers during the months after the Confeder-

ate surrender. The gunmen were not necessarily former Confederates: a drunken

soldier of the 1st Louisiana Infantry, a white Union regiment recruited in the state,

shot dead Sgt. Joseph Smith of the 11th USCA as Smith’s regiment arrived to join

the Donaldsonville garrison in July. In August, a civilian in South Carolina gunned

down 2d Lt. James T. Furman of the 33d USCI with one round in the back followed

by another in the head.

50

Assassinations continued during the fall. In October, persons near Okolona,

Mississippi, killed Pvt. James Roberts of the 108th USCI and wounded a white

cavalryman. Efforts to arrest the culprits failed. Days later, Sgt. George Montgom-

ery and Pvt. William Howell, both of the 42d USCI, were waylaid en route from

Decatur, Alabama, to a nearby town and bludgeoned to death. Again, the killers

escaped. Opportunistic killings continued through the following months, with civil

juries unwilling to convict and Army ofcers, sometimes uncertain of their own

authority, reluctant to act decisively. Black soldiers and their white ofcers were by

no means the only victims, but as their regiments came to form the bulk of the oc-

cupation force, they offered a conspicuous target even as they stoked white South-

erners’ racial ire. Infantry, well suited to accompany Freedmen’s Bureau agents on

routine visits to plantations, was seldom able to catch eeing murderers, and the

last volunteer cavalry regiments were rapidly mustering out.

51

Meanwhile, state militias across the South enforced laws that deprived freed-

men of weapons. At La Grange, Tennessee, the Bureau agent thought that it was

part of a program “to reduce the Freedmen to their former condition.” An ofcer

49

Peck to Reynolds, 31 Oct 1865; Maj Gen O. O. Howard to Col S. Thomas, 27 Dec 1865

(R–148), NA M826, roll 11.

50

Col J. H. Sypher to Asst Adj Gen, 10 Jul 1865, Entry 402, Post of Donaldsonville, Letters

Sent (LS), pt. 4, Mil Installations, RG 393, NA; Descriptive Book, Co E, 11th USCA, Regimental

Books, RG 94, NA. Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers

and White Ofcers (New York: Free Press, 1990), p. 215, describes Furman’s death. An account of a

white soldier’s murder in South Carolina is in the New York Tribune, 25 November 1865.

51

Post of Columbus, SO 92, 5 Oct 1865, and 2d Lt A. Noble to 1st Lt W. Clendennin, 7 Oct 1865,

both in 108th USCI; Maj G. W. Grubbs to Maj J. B. Sample, 13 Oct 1865, 42d USCI; Capt S. Marvin

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

480

in Louisiana reported that in parishes southwest of New Orleans, the militia was a

“great source of annoyance and irritation to the blacks,” who believed that the pur-

pose of the militia was “to crush out what freedom they now enjoy.” White Union-

ists in West Feliciana Parish petitioned the general commanding federal troops in

the state to establish a garrison there to counteract the local militia company, “its

legitimate purposes subverted to subserve the wicked designs of those malicious

persons, who only strike in the dark.” The petitioners praised the men of the 4th

USCC who had camped nearby for a month, imposing “an unwonted quiet and or-

derly state of affairs.” In South Carolina, the militia worried Army ofcers as well

as freedmen. “All of the ofcers and men of these companies have seen service,”

the general commanding at Darlington wrote. Most members of the twelve militia

companies in his district had “arms of some description,” the general wrote, “and

. . . they are superior in numbers to the total Military force of the United States.”

The commanding ofcer at Camden tried to constrain the local militia company by

forbidding it to assemble with arms.

52

The militia companies clearly represented an effort by white Southerners to re-

vive the antebellum system of mounted rural patrols that restricted travel by slaves

and punished summarily those who left their homes without passes. The intention

was to reduce black Southerners to subservience. State ofcials preferred to ignore

the obvious parallel, claiming instead that the purpose of the militia, apart from the

suppression of general lawlessness, was to avert a black rebellion at the end of the

year.

53

In October, news of an uprising by black Jamaicans that left more than twenty

persons of European or mixed ancestry dead inamed fears of a racial insurrection

in the American South. From coastal North Carolina to Arkansas, worried white

residents petitioned civil and military authorities for protection. Just as common

were reports from ofcers of black regiments deriding the idea of an uprising that,

according to rumor, the freedmen planned for Christmas or New Year’s Day. Col.

Frederick M. Crandal of the 48th USCI dismissed “the fears of the people” around

Shreveport, Louisiana, and attributed the rumors to recalcitrant former Confeder-

ates “who are anxious that all the trouble possible should be made . . . and who get

up these stories for the purpose of embarrassing the Government.” At Memphis,

Maj. Arthur T. Reeve of the 88th USCI was “condent that no conspiracy ex-

ists.” The Freedmen’s Bureau agent at Washington, North Carolina, 2d Lt. Josiah

G. Hort of the 30th USCI declared the rumors “utterly groundless,” and the state

assistant commissioner, General Whittlesey, called “these fears . . . relics of the

past, nervous convulsions of the dead body of slavery.” As the end of December

approached, and with it the imagined insurrection, even the governor of South

to Capt A. S. Montgomery, 20 Nov 1865, with Endorsement, Brig Gen C. A. Gilchrist, 27 Nov 1865,

58th USCI; all in Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. Tuttle to Williams, 21 Dec 1865.

52

S. H. Melcher to Brig Gen C. B. Fisk, 12 Dec 1865 (K–59), NA M752, roll 21; Capt T. Kanady

to 1st Lt Z. K. Wood, 23 Dec 1865 (L–896–DL–1865), and John Wible et al. to Maj Gen E. R. S.

Canby, 29 Nov 1865 (F–262–DL–1865), both in Entry 1757, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Brig Gen W. P.

Richardson to Lt Col W. L. M. Burger, 7 Dec 1865, Entry 4112, Dept of the South, LR Relating to

Freedmen, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; J. L. Orr to Maj Gen D. E. Sickles, 13 Dec 1865, Entry 4109, pt. 1, RG

393, NA; Zuczek, State of Rebellion, pp. 13, 20.

53

Carter, When the War Was Over, pp. 191–203.