Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

491

of black soldiers, occurred in Memphis, a major port on the Mississippi River that

had seen its black population quadruple, to eleven thousand of the city’s twenty-

eight thousand residents, since Union troops arrived there in May 1862. The 3d

USCA had been part of the Memphis garrison since the regiment was raised in

1863, and the soldiers’ dependents lived in shantytowns near Fort Pickering and

other posts on the edge of the city. Their presence gave rise to “bitterness of feeling

. . . between the low whites and blacks,” a Freedmen’s Bureau inspector reported.

The 3d USCA mustered out on the last day of April 1866.

77

The trouble began that evening with a hostile encounter between four city po-

licemen and a few black soldiers who were waiting for their discharges. The next

day the conict became more serious, with city police arresting soldiers who were

drinking while they awaited their nal pay and discharges. A little later, police

red on shantytown residents. By afternoon, a mob of white rioters had arrived on

the scene. The muster-out of the 3d USCA had left Maj. Gen. George Stoneman,

the department commander, with only 150 regulars of the 3d Battalion, 16th U.S.

Infantry, in the Memphis garrison. Stoneman later told congressional investigators

that the troops numbered barely enough to protect government property in the city,

and that this had kept him from intervening in the riot. Just after the riot, a Freed-

men’s Bureau agent reported, the department commander had said that the newly

recruited infantry could not be trusted to restore order—that he feared that they

would join the white mob.

78

By 3 May, when civic leaders nally asked Stoneman to declare martial law,

two white men and at least forty-six black people lay dead. More than thirteen of

them were soldiers of the 3d USCA or discharged veterans of other black regi-

ments. Besides attacking the shantytown and its residents, the mob had destroyed

three black churches, eight schools, and about fty freedpeople’s homes. The

Memphis Avalanche was a newspaper with a national reputation for its inamma-

tory prose. “Soon we shall have no more black troops among us,” its editor exulted.

“Thank heaven the white race are once more rulers of Memphis.”

79

By mid-June 1866, only eighteen black regiments continued in service, the last

vestige of the Union armies that had occupied the South a year earlier. Seven of

them had gone from Virginia to Texas with the XXV Corps and still manned posts

along the lower Rio Grande and the Gulf Coast; two regiments, the 10th USCA and

the 80th USCI, were at New Orleans and the forts around the city; two, the 57th

and 125th USCIs, were scattered at small posts in New Mexico; the 107th USCI

guarded government property in and near Washington, D.C.; and the 37th USCI

to Maj Gen W. D. Whipple, n.d. (T–814–AGO–1866, f/w Annual Rpts), NA M619, roll 533; Return,

16th U.S. Inf, Jun 1866, NA Microlm Pub M665, Returns from Regular Army Inf Rgts, roll 174.

77

Maj Gen G. Stoneman to Lt Gen U. S. Grant, 13 May 1866 (T–328–AGO–1865, f/w T–287–

AGO–1866), NA M619, roll 519; Maj T. W. Gilbreth to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 22 May 1866, NA

Microlm Pub M999, Rcds of the Asst Commissioner for the State of Tennessee, BRFAL, roll

34 (quotation); Carter, When the War Was Over, pp. 248–50; Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 261–63;

Kevin R. Hardwick, “‘Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead and Damned’: Black Soldiers and the

Memphis Riot of 1866,” Journal of Social History 27 (1993): 109–28.

78

Brig Gen B. P. Runkle to Maj Gen C. B. Fisk, 23 May 1866, NA M999, roll 34; “Memphis

Riots and Massacres,” 39th Cong., 1st sess., H. Rpt. 101 (serial 1,274), p. 2.

79

“Memphis Riots and Massacres,” pp. 50–52; John H. Franklin, Reconstruction After the Civil

War, 2d ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), p. 63 (quotation).

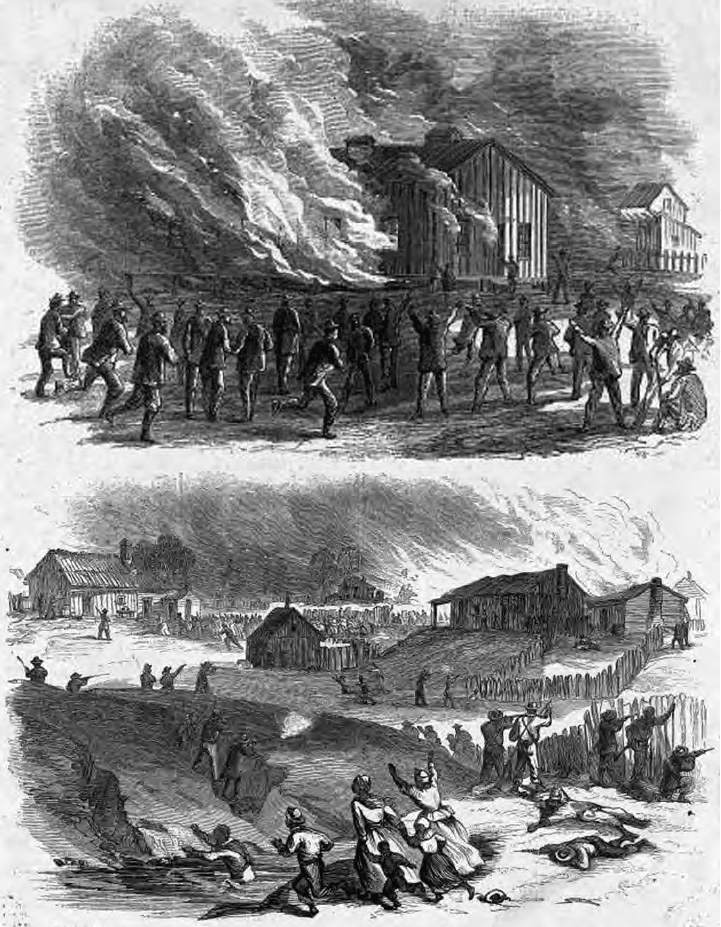

An artist imagines the destruction of the shantytown near Fort Pickering where

dependents and hangers-on of the 3d U.S. Colored Artillery lived. The Memphis Riot

began hours after the regiment mustered out, 30 April 1866. It was one of several similar

occurrences—white-on-black violence with a lopsided casualty list—that occurred in the

former Confederacy that spring and summer.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

493

manned coastal forts in North Carolina. Only ve of the regiments that remained

in the former Confederate states had much to do with enforcement of Reconstruc-

tion policies: the 56th USCI, headquartered at Helena, Arkansas; the 65th, at Lake

Providence in northeastern Louisiana; the 80th, at towns along the Red River in

western Louisiana and northeastern Texas; the 82d, at Pensacola; and the 128th, in

South Carolina.

80

The presence of black regiments as far west as New Mexico resulted from

General Grant’s wish, expressed to General Sherman early in 1866, “to get some

colored troops out on the plains.” White volunteers, many of them from west-

ern states and territories, had manned forts along major routes to California, New

Mexico, and Oregon for most of the war, and they brought with them their local at-

titudes toward American Indians. Colorado militia had attacked a village of peace-

ful Cheyennes in 1864, igniting more than two years of warfare. Grant hoped that

“colored and regular troops,” with no special axe to grind, could guarantee “the

rights of the Indian . . . [so] as to avoid much of the difculties . . . heretofore expe-

rienced.” As it turned out, only two black regiments were available for assignment,

and they served in New Mexico at a time when it was one of the quietest parts

of the West. Scattered companies of the regiments undertook repairs on the forts

where they served and sometimes pursued Indian stock thieves. In this, they were

no more successful than the black infantry regiments on the lower Rio Grande or

infantry in the South chasing mounted white terrorists.

81

Early in the summer of 1866, two noteworthy events occurred in Washing-

ton. On 3 July, General Howard wrote to General Grant from Freedmen’s Bureau

headquarters in Washington, mentioning three shootings of Bureau ofcers and

freedmen that had occurred recently in Georgia, Mississippi, and Virginia. “The

civil authorities have failed, and are afraid to act,” Howard told Grant. “The simple

issuing of an order . . . would go far to prevent these attacks upon ofcers of the

Government.” Three days later, Grant issued a general order that authorized “De-

partment, District and Post Commanders” in the South to arrest and detain anyone

charged with “offenses against ofcers, agents . . . and inhabitants of the United

States, irrespective of color,” when civil authorities failed to act. Army ofcers

were to hold the prisoners “until . . . a proper judicial tribunal may be ready and

willing to try them.” The legal status of the occupation force in the South had been

ambiguous since the president had declared the rebellion at an end in April. Grant’s

language left the execution of the order to the judgment of local commanders and

did little to clarify the situation while exposing Army ofcers to endless civil law-

80

Dyer, Compendium, pp. 1720–40; see also order books and letter books of regiments named

in Regimental Books, RG 94, NA.

81

Lt Gen U. S. Grant to Maj Gen W. T. Sherman, 3 Mar 1866, in The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant,

ed. John Y. Simon, 30 vols. to date (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University

Press, 1967– ), 16: 93 (“to get some”) (hereafter cited as Grant Papers); Lt Gen U. S. Grant to Maj

Gen W. T. Sherman, 14 Mar 1866, in Grant Papers, 16: 117 (“colored and”). For black soldiers in

the eld in New Mexico, see Capt G. W. Letterman to Post Adj Ft Cummings, 5 Oct 1866, and Capt

R. B. Foutts to Maj C. H. De Forrest, 24 Nov 1866, 125th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. Francis B.

Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C.:

Government Printing Ofce, 1903), 2: 427–30, shows only six engagements in New Mexico during

the time the 57th and 125th USCIs served there.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

494

suits. The order might have had greater effect if there had been enough troops to

cover the region, but there were not.

82

Congress attempted to remedy this lack on 28 July, the last day of the session,

by passing an act that increased the size of the Army. The peacetime establish-

ment expanded by four regiments of cavalry, two of them with black enlisted men.

The nine infantry regiments that had been raised in 1861, with three battalions of

eight companies each, were broken up into twenty-seven ten-company regiments

to match the organization of the ten senior infantry regiments. This added fty-

four infantry companies to the force. In addition, the act created four new infantry

regiments with black enlisted men (another forty companies) and four regiments

of wounded veterans, which, when organized, garrisoned Washington, D.C.; Nash-

ville, Tennessee; and posts along the Canadian border, releasing regiments of able-

bodied troops for service in the South or West. In all, the act added 48 companies

of cavalry and 134 of infantry—more than fourteen thousand ofcers and men—to

the Regular Army as it had existed since the spring of 1861. Still, the new organi-

zation added little to the enforcement of congressional Reconstruction measures;

for while more than one-third of the infantry served in the South for at least a few

years, all of the new mounted regiments went west.

83

As commanding ofcers in the South looked around them in the summer

of 1866, what they saw was not encouraging. Lt. Col. Orrin McFadden of the

80th USCI reported “very little change ” around Alexandria, in central Louisiana.

“Union men whether of northern or southern birth are living in extreme jeopardy

of their lives.” He mentioned “extremely bitter feeling” against Henry N. Frisbie,

former colonel of the 92d USCI, who ran a plantation some twenty miles from

Alexandria. “The only ground . . . for this hostility,” McFadden wrote, “is the fact

that Col. F. treats his laborers decently, and accords to them the common rights of

humanity.” Besides legal harassment in the courts, Frisbie had received threats that

led him to arm his plantation hands that spring.

84

The number of former Union ofcers who stayed in the South to farm after the

war is uncertain, but there were certainly scores, if not hundreds, of them among

the thousands of Northerners who took up plantation agriculture. Frisbie was not

the only one to arm his workers; some thirty-ve miles northeast of Vicksburg,

Morris Yeomans’ plantation was home to fty veterans of his former regiment,

the 70th USCI. Surrounded by “those who have not ceased to be our constant and

unrelenting foes,” they went “thoroughly armed,” Yeomans told a staff ofcer at

82

Maj Gen O. O. Howard to Lt Gen U. S. Grant, 3 Jul 1866, quoted in Grant Papers, 16:

229. The text of Grant’s order is on p. 228. Queries from ofcers in the South about the effects of

Johnson’s proclamation and Grant’s order appear on p. 229 and in McPherson, Political History,

p. 17. See also James E. Sefton, The United States Army and Reconstruction, 1865–1877 (Baton

Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967), pp. 77–82, 92–94; Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 239–

51; Simpson, Reconstruction Presidents, pp. 92–99.

83

Heitman, Historical Register, 2: 601, 604. Troop stations appear in the Army and Navy

Journal, 28 July 1866 and 20 July 1867. Heitman, Historical Register, 2: 601, shows ve of six

mounted regiments as having ten companies each, but the Army standardized the size of cavalry

regiments at twelve companies in 1862. Mary L. Stubbs and Stanley R. Connor, Armor-Cavalry,

Part 1: Regular Army and Army Reserve, U.S. Army Lineage Series (Washington, D.C.: Ofce of

the Chief of Military History, 1969), p. 16.

84

Lt Col O. McFadden to 1st Lt N. Burbank, 12 Jul 1866, Entry 25, Post of Alexandria, LS,

pt. 4, RG 393, NA; H. N. Frisbie to Maj W. Hoffman, 22 May 1866, Entry 1757, pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

495

department headquarters. A gang had been stealing mules from plantations run by

Unionists and “disarming all Negroes that come within their reach.” Some of its

members had been seen reconnoitering Yeomans’ plantation. The former colonel

also reported the murders of seven freedmen in his neighborhood since the begin-

ning of the year.

85

Although it made sense for a former ofcer of U.S. Colored Troops to buy or

lease land where discharged soldiers from his regiment offered a disciplined labor

force well acquainted with the use of rearms, the prospects of success were still

not great. Floods and insect pests combined to ruin many Northern planters before

three growing seasons had passed. Frisbie left his plantation for New Orleans,

and Yeomans returned to Ohio, where he had rst joined a volunteer regiment in

1862.

86

The handful of black regiments that remained on duty in the rural South tried

to maintain order. “Many abuses to the freedmen are being perpetrated,” the colo-

nel of the 80th USCI complained to department headquarters from Shreveport that

September, “and the parties go free from punishment . . . , as we are powerless to

reach them with infantry troops. . . . Civil authorities will not protect the negro

when calling for justice against a white man. The people are as strongly united

here against . . . the U.S. Government as . . . [at] any time during the rebellion.”

Despite the ineffective performance of infantry, the colonel wrote, “Take away the

troops and northern men must leave or foreswear every principle of true loyalty

and manhood and truckle to the prejudices of the masses.” As if to underscore his

point, ofcers of the 65th USCI on the other side of Louisiana reported failures

throughout the summer to arrest mounted lawbreakers around Lake Providence,

on the Mississippi River. Ofcers of the regular infantry, which had necessarily

taken on an increasing share of occupation duty as black regiments mustered out

throughout the year, complained of similar unsatisfactory results.

87

While federal troops in the South struggled to control what seemed to be a

rising tide of disorder during 1866, Congress and the president became increasingly

estranged. Although the fall elections had increased Republican majorities in both

houses, Johnson continued to veto Reconstruction laws and to see his vetoes

overridden. He tried to obstruct passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, a carefully

worded measure that conferred citizenship on native-born freedmen and reduced

the congressional delegations of states that barred them from the polls because of

their race. When his opposition further excited northern editorial opinion against

85

M. Yeomans to Col M. P. Bestow, 20 Jun 1866, Entry 2433, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Lawrence N.

Powell, New Masters: Northern Planters During the Civil War and Reconstruction (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1980), pp. xiii, 28–29, 50.

86

Currie, Enclave, pp. 151–52, 156–59; Taylor, Louisiana Reconstructed, pp. 343–45; Michael

Wayne, The Reshaping of Plantation Society: The Natchez District, 1860–80 (Urbana: University of

Illinois Press, 1990), pp. 61–66; Roster, Surviving Members of the 95th Regiment, O.V.I. [Columbus,

Ohio: Champlin Press, 1916].

87

Col W. S. Mudgett to Maj J. S. Crosby, 6 Sep 1866, 80th USCI, and 1st Lt W. P. Wiley to 1st

Lt N. Burbank, 8 Jul 1866, 65th USCI, both in Entry 57C, RG 94, NA; Capt A. D. Bailie to AAG

[Assistant Adjutant General] Dept of the Gulf, 27 Sep 1866, Entry 1756, pt. 1, RG 393, NA. For

regular ofcers bemoaning the lack of cavalry in Florida, see Col J. T. Sprague to Brig Gen C.

Mundee, 31 Aug 1866, f/w Maj Gen J. G. Foster to Lt Col G. Lee, 11 Sep 1866 (F–25–DG–1866),

Entry 1756, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; in South Carolina, 1st Lt C. Snyder to Lt Col H. W. Smith, 21 Jul

1866, NA M869, roll 34.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

496

him, General Grant urged him to modify his stance, but to no effect. Southern

state legislatures refused to ratify the amendment. In turn, Congress passed the

rst of several Reconstruction Acts. It assigned ten Southern states to ve military

districts, within each of which an Army general would oversee the administration

of justice until the constitutions of the occupied states were judged to conform to

the federal constitution. On 2 March 1867, Johnson vetoed the bill and Congress

once again overrode his veto.

88

The Reconstruction Act and the events that occurred after it do not gure

in the history of the U.S. Colored Troops. The day before the act became law,

the last black regiment on Reconstruction duty, the 80th USCI, mustered out

in Louisiana. Still in service were the 117th USCI, the last regiment of the

long-since disbanded XXV Corps on the lower Rio Grande, and the 125th

USCI at posts in New Mexico. The 117th mustered out in August and headed

for Louisville for nal payment and discharge. In the fall, companies of the

125th gathered in northern New Mexico and Colorado and followed the Santa

Fe Trail east to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where the regiment mustered out

on 20 December 1867. The last regiments of Civil War volunteers were out of

service. About three thousand enlisted men, with representatives from most U.S.

Colored Troops organizations, tried the life of the peacetime Army in one of the

new black regiments of cavalry or infantry, as did roughly one hundred of the

ofcers. The vast majority—more than 95 percent—returned to civilian life. For

the tens of thousands who had served in the ranks, their discharges released them

into a new world in which most of them were free for the rst time; a world that,

whatever its imperfections, their own efforts had helped to shape.

89

88

Foner, Reconstruction, pp. 251–80; Simpson, Reconstruction Presidents, pp. 109–15;

Trefousse, Andrew Johnson, p. 274. A complaint of increasing violence in Florida is Maj Gen J. G.

Foster to Maj Gen G. L. Hartsuff, n.d. [early Oct 1866] (F–28–DG–1866) (quotation), Entry 1756, pt.

1, RG 393, NA; in South Carolina, Col G. W. Gile to Lt Col H. W. Smith, 1 Jul 1866, NA M869, roll

34; in Arkansas, Maj Gen J. W. Sprague to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 1 Sep 1866, NA M979, roll 23.

89

125th USCI, Regimental Books, RG 94, NA; William A. Dobak and Thomas D. Phillips,

The Black Regulars, 1866–1898 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001), pp. 24, 293; Dyer,

Compendium, p. 1739.

Although the presence of nearly 4 million slaves in the Confederacy and the

loyal border states made it inevitable that black people would play a prominent

role in the Civil War, the federal government’s eventual decision to enlist black

soldiers was as hesitant as its approach to the entire question of emancipation. In

the rst place, the prevailing racial attitudes of white Americans meant that the

presence of black people would be discounted, if not ignored, as much as possible

and for as long as possible. Moreover, the geopolitical necessity of securing the

loyalty of slaveholding border states ensured that the approach would be hesitant

and oblique. Rail connections to the nation’s capital ran through Maryland; beyond

the Mississippi River, the state of Missouri controlled routes to the Pacic Coast

and the Rocky Mountains, both sources of wealth necessary to the federal treasury;

between Maryland and Missouri lay Kentucky, with its river boundary shared by

three large and populous free states. Until the border states were secured to the

Union, Abraham Lincoln and his cabinet believed that they had to proceed cau-

tiously. Early attempts to preserve the Union were thus tentative and soft. In the

opening months of the conict, Union generals assured white Southerners that they

came only to reassert federal authority, not to free slaves. Only in July 1861, when

a Confederate army rebuffed an attempt to oust it from the vicinity of Washington,

D.C., did the Northern public accept the fact that the country faced a long war.

1

During the next year, Union armies advanced on all fronts, despite well-pub-

licized reverses in Virginia. They occupied Nashville, New Orleans, Norfolk, and

Memphis; marched through Arkansas; and established beachheads in the Carolinas

and Florida. Everywhere they went, the region’s enslaved black residents thronged

their camps, hoping for an escape from bondage. Army quartermasters and engi-

neers quickly put the new arrivals to work, often competing for their services with

agents of the Treasury Department who wanted the freedpeople settled on planta-

tions and producing cotton to nance the war. Meanwhile, the president rejected

attempts by generals in Missouri, South Carolina, and elsewhere to free slaves or

to enlist them as soldiers. In the summer of 1862, when the federal advance had

1

U.S. Census Bureau, Agriculture of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.: Government

Printing Ofce, 1864), pp. 223–45; Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy

Toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 8–11,

23–46.

Conclusion

Chapter 15

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

498

moved beyond the still-loyal border states and reached well into the Confederacy,

public opinion in the North had matured enough to allow Congress to pass an act

that prohibited soldiers from returning escaped slaves to their masters.

2

By that summer, Lincoln had decided on a policy of Emancipation. He waited

to announce it until Union arms had turned back a Confederate thrust into Mary-

land. Even then, he declined to alienate the white population in parts of the South

that federal troops had already occupied by freeing slaves there. The Emancipation

Proclamation applied only to those slaves who were beyond the reach of Union au-

thority. Nevertheless, the steady advance of federal armies assured that many more

of the thousands still enslaved would be free before another year ended. Vicksburg

and Port Hudson fell in July 1863, allowing Union control of the Mississippi Riv-

er; Chattanooga, a rail center on the upper Tennessee River, followed two months

later. In January 1864, federal soldiers crossed the state of Mississippi from west

to east and back again before boarding riverboats and railroad cars to join a Union

drive into northwestern Georgia. Each of these advances added thousands more

names to the rolls of freedpeople working for the Union, whether on plantations

growing food and cotton; as teamsters and longshoremen for Army staff ofcers;

or, nally, as soldiers themselves.

The question arose at once: what functions should these new troops perform?

Moving as cautiously as ever, Lincoln specied in the Emancipation Proclamation

that they were “to garrison forts . . . and other places.” Yet black soldiers in Kansas

and South Carolina had already undertaken duties of a different kind, escorting

wagon trains and conducting raids well outside the limits of federal garrisons. Sev-

eral times, they had exchanged shots with the enemy. As happened often during a

war in which federal policy evolved in reaction to events, practices in the eld were

far in advance of pronouncements from Washington.

3

Assignment of new black regiments to stations in the wake of the federal ad-

vance had sound precedents. Union generals had always taken great care to protect

their lines of communications. Even before the rst shots were red, Lt. Gen. Win-

eld Scott thought that one-third of the force necessary to crush secession would

have to serve at garrisons in occupied territory. In December 1863, the Army of

the Potomac counted 94,151 ofcers and men present, while those assigned to the

Defenses of Washington numbered 33,905, including 12 white regiments of heavy

artillery—more than the number of black artillery regiments raised to protect river

ports from Paducah to New Orleans. Together with federal garrisons in Maryland

and along the line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in West Virginia, soldiers

guarding the rear of the Army of the Potomac amounted to more than two-thirds the

strength of the offensive force. The situation was similar west of the Appalachians,

where the XVI Corps, at Memphis and other points in Tennessee, nearly equaled

in size to the rest of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army, camped at more ad-

vanced posts in Alabama and Mississippi. Stationed around Nashville were more

2

On competition between military and civilian demands for black laborers, see above, Chapters

2, 5–8.

3

The text of the Emancipation Proclamation in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of

the Ofcial Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 (Washington, D.C.:

Government Printing Ofce, 1880–1901), ser. 3, 3: 2–3 (hereafter cited as OR).

Conclusion

499

than twelve thousand soldiers, roughly the same number as served in one of the

corps that made up the Army of the Cumberland, which wintered at Chattanooga.

4

To suppose that garrison duty or guarding a railroad removed troops from the

likelihood of ghting is to ignore the uid nature of the war, especially west of

the Appalachians. Infantry escorting a wagon train might receive little warning

before nding itself heavily engaged with Confederate raiders, as could happen

anywhere from Arkansas to Virginia. The Confederate cavalry leader Nathan B.

Forrest was able to raid as far north as the Ohio River, where the 8th U.S. Colored

Artillery served in the garrison of Paducah, Kentucky, in the spring of 1864. That

December, the Confederate Army of Tennessee camped outside Nashville for more

than a week before being driven off, although Union troops had occupied the city

for nearly three years. Black soldiers who had spent the previous year guarding

the Nashville and Northwestern Railroad helped to repel this last Confederate of-

fensive. Even as late as the last twelve months of ghting, Union troops far in the

rear of advancing federal armies might receive a visit from a formidable body of

Confederates at almost any time.

5

While the Lincoln administration may have intended a defensive role for the

new black regiments, Union generals in the eld did not hesitate to put them into

action. The best results came at rst from operations for which the troops were

already well adapted, such as the early riverine expeditions in South Carolina

and Florida, where locally recruited black soldiers were operating on their home

ground. New regiments tended to do less well when their rst battle was an assault

on enemy trenches: witness the disasters that befell the Louisiana Native Guards at

Port Hudson in May 1863 and the 54th Massachusetts at Fort Wagner less than two

months later. Still, the survivors of those misconceived attacks became seasoned

campaigners. In February 1864, seven months after the reverse at Fort Wagner, the

54th Massachusetts helped to save the Union army at Olustee, Florida, while a new

black regiment in the same ght, the 8th United States Colored Infantry (USCI),

had trouble simply loading and ring its weapons. The 8th, in its turn, did well

eight months later during the fall campaign in Virginia. So did the 73d USCI (the

1st Louisiana Native Guards of the Port Hudson assault) when it helped to capture

Fort Blakely, near Mobile, in the last days of the war.

6

Black soldiers clearly had little trouble carrying out assignments when they

relied on knowledge they already possessed or when they received adequate train-

ing. Unfortunately for them, that training could be a matter of chance. It might

depend on the preoccupations of a colonel commanding a new regiment who led

his men into battle without having taught them to load and re their weapons or on

the racial beliefs of a general commanding a garrison, who might see black soldiers

only as a source of manual labor and deny them time for drill. Although white

4

OR, ser. 1, vol. 29, pt. 2, pp. 598, 608–09, 611, 614; vol. 31, pt. 3, pp. 548–49, 564. Wineld

Scott, Memoirs of Lieut.-General Scott (New York: Sheldon, 1864), p. 627.

5

For the attack on a Union wagon train at Poison Spring, Arkansas, see above, Chapter 8; for

Forrest’s attack on Paducah, Chapter 7; for black soldiers’ part in the battle of Nashville, Chapter 9.

Other Confederate raids on wagon trains are in Chapters 7, 9, and 11.

6

On riverine operations in South Carolina and Florida, see above, Chapters 2 and 3; on Fort

Wagner, Chapter 2; on Port Hudson, Chapter 4; on Olustee, Chapter 3; on the 8th USCI in Virginia,

Chapters 11 and 12; on Mobile, Chapter 5.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

500

soldiers and black civilian laborers also wielded axes, picks, and shovels, written

complaints from commanders of black regiments show that high-ranking ofcers

were apt to put their racial opinions into practice wherever Union troops served.

7

An important factor in the training of new black regiments was the selection

of ofcers. Most of these regiments were raised locally in the South. Their of-

cers came from whatever white regiments happened to be on the spot. Most of

these ofcers received their appointments long before an examining board met to

judge their qualications. The system could be effective, as when Col. Embury

D. Osband picked men from his previous regiment to lead the 3d U.S. Colored

Cavalry or when Brig. Gen. Edward A. Wild drew up his list of ofcers for the

35th USCI. At other times, the results could be scandalously bad. The 79th, 83d,

88th, 89th, and 90th USCIs—mustered in between August 1863 and February

1864— had to be disbanded on 28 July 1864, with the enlisted men reassigned

and the ofcers mustered out. Ofcers of the disbanded regiments who thought

they were competent to face an examining board could apply for reinstatement.

Those who passed the examination joined a list of names to ll vacancies in the

remaining black regiments within the Department of the Gulf. Competent or

incompetent, nearly all of the mustered-out ofcers had served for between ve

and eleven months before the shabby state of their regiments became evident

enough to move authorities to act.

8

Prevalent racial attitudes in the nineteenth-century United States deter-

mined that white men would lead the new regiments. Since the prejudices of

white Americans dictated that the country would begin the war with an all-

white Army, when the time came two years later to enlarge the force by more

than one hundred new black regiments the only veterans available to ll of-

cers’ posts were white men. Moreover, ofcers had to be literate, and genera-

tions of unequal education had made book learning rare among black people

even in the North. Although War Department policy at this time excluded po-

tential black ofcers from consideration, there were few alternatives, anyway;

the immediate need for several thousand experienced men to lead the black

regiments dictated that the successful applicants would come from the all-

white army that already existed.

9

In September 1864, with Sherman’s army in Atlanta at last and prospects for

the fall election looking up, Lincoln still maintained that his “sole avowed object”

in prosecuting the war was “preserving our Union, and it is not true that it has since

been, or will be, prossecuted . . . for any other object.” That sole aim had driven the

president to many shifts, emancipation among them. Emancipation launched black

7

On lack of preparedness going into battle, see above, Chapters 3, 6, 11, and 12. On the

disproportionate amount of fatigue duty allotted to black troops, see Chapters 2, 5, 7, and 12.

8

Ofcial Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States, 8 vols. (Washington, D.C.:

Adjutant General’s Ofce, 1868), 8: 261, 269–71.

9

Dudley T. Cornish, The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861–1865 (New York:

Longmans Green, 1956), p. 201; Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of

Black Soldiers and White Ofcers (New York: Free Press, 1990), pp. 35–36; Ira Berlin et al., eds.,

The Black Military Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 18–20, 303–12.

Leon F. Litwack, North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790–1860 (Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1961), pp. 113–17, 131–39, describes educational opportunities for blacks in the

North.