Dobak William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

461

and slavery and pave the way for the state’s representation in Congress. Delegates

to the convention had to have been eligible voters in the 1860 election—that is,

white—and to have taken an oath of allegiance to the United States since the ght-

ing ended. During the next six weeks, he issued similar proclamations for Ala-

bama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Texas, and South Carolina. These seven proc-

lamations, and the Unionist state governments established in Arkansas, Louisiana,

Tennessee, and Virginia during the war, set all the former Confederate states on the

road to reunion.

8

More pressing even than political matters was the business of tending and

harvesting that year’s crops, for the federal government was already feeding

thousands of destitute Southerners, black and white, and sought to reduce the -

nancial burden. Efcient management of the agricultural labor force would help

to diminish government expenditures just as surely as did the rapid mustering

out of Union regiments and might forestall a famine that was otherwise sure to

come with winter. Unfortunately for those who hoped to manage the laborers,

many of the South’s former slaves were absent from their home plantations that

spring and summer. Reasons for the mass movement were many. Some of the

migrants searched for relatives from whom they had been separated, whether

by slave sales before the war or by forced removal from the paths of advanc-

ing Union armies during the ghting. Other migrants wished to avoid the kind

of confrontation with former masters that the change from slave to free labor

was sure to bring. Still others merely sought safety in numbers within growing

black urban communities, for freedom meant that former slaves were no longer

protected property, but instead were fair game for any evil-tempered white man

with a deadly weapon.

9

Chaplain Homer H. Moore of the 34th USCI traveled across northern Florida in

May and June. When the ofcial announcement of freedom in the Department of the

South came in late May, he said, “large numbers of negroes left their homes, & began

ocking into the towns, causing great inconvenience to the Military Authorities, &

great danger to the growing crops.” Moore and two civilian ofcials set out across

the state to investigate conditions and to try to explain the workings of a free labor

system to former masters and former slaves alike. “In so far as it was the purpose of

our mission to induce the negroes to remain at home, & work for wages, we think

we were very successful,” he reported, “for having heard from their masters that

they were free, but still having to work very much the same as before, they naturally

believed they were imposed upon; & that to secure perfect freedom they must get to

some place occupied by U.S. troops. But hearing from us, unquestionable Yankees,

that they were free wherever they were, & that the Government would protect them,

8

Brooks D. Simpson, The Reconstruction Presidents (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas,

1998), pp. 73–75; Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton,

1989), pp. 210–11, 216–22. Texts of the amnesty and state government proclamations are in OR, ser.

2, 8: 578–80, and ser. 3, 5: 37–39.

9

Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Knopf,

1979), pp. 305–16; Hahn et al., Land and Labor, pp. 7, 80; statistic in Dan T. Carter, When the War

Was Over: The Failure of Self-Reconstruction in the South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University

Press, 1985), p. 157.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

462

but that they would have to work nevertheless to live they became reconciled to the

new state of things.”

10

While only the tiniest fraction of former slaves—those whose masters had allowed

them to hire out their labor before the war—had any idea of the workings of a free labor

system, many former masters had little better understanding. One of the Northern re-

porters who ocked to the South in 1865 had an illuminating discussion with a former

slaveholder in South Carolina. “All we want,” the planter told him, “is that our Yankee

rulers should give us the same privileges with regard to the control of labor which they

themselves have. . . . In Massachusetts, a laborer is obliged by law to make a contract

for a year. If he leaves his employer without his consent, or before the contract expires,

he can be put in jail. . . . All we want is the same or a similar code of laws here.” The

reporter denied that such a law existed in any Northern state. “How do you manage

without such laws?” the planter asked. “How can you get work out of a man unless you

compel him in some way?” Even a leading politician like James W. Throckmorton of

Texas expressed privately his yearning “to adopt a coercive system of labor.”

11

Although Northerners had a better idea of how a free labor system operated than

the planters did, many of them, including high-ranking Army ofcers and Freedmen’s

Bureau ofcials, were unsure about the future of free labor in the South. At Memphis,

the eld agent reported in mid-August:

Many freed people prefer a life of precarious subsistence and comparative idleness

in the suburbs of the city, to a more comfortable home and honest labor in the

country. . . . I propose . . . to take efcient steps to remove that portion . . . who

have no legitimate means of support, and distribute them in the Country, where

their labor is wanted, and where they will have much better opportunities of leading

useful and happy lives.

Six weeks later, a new Bureau ofcial in the city noted that “quite a large number of va-

grants were arrested by the colored troops, & by force of arms, were sent to the country

to work on plantations.”

12

At the same time that black soldiers at Memphis were rounding up reluctant plan-

tation labor, a Freedmen’s Bureau inspector found successful cotton crops in Arkansas

counties where black regiments had guarded the workers for more than two years.

Three ofcers from those regiments were serving as Bureau agents at places the in-

spector visited. Near Helena, he noticed that cotton “on the small leases worked by

colored lessees on their own accounts is decidedly superior to that cultivated by them

as hired hands.” Freedmen on a plantation that had belonged to Confederate Brig. Gen.

Gideon J. Pillow hoped to clear enough money from the 1865 crop to buy the land they

had been farming. Near Pine Bluff, a government farm with 876 residents, “mostly

disabled men, women and children,” managed to farm 250 acres of cotton and 150 of

10

H. H. Moore et al. to N. C. Dennett, 12 Jun 1865 (E–521), NA Microlm Pub M752, Registers

and Letters Received (LR) by the Commissioner of the BRFAL, roll 20.

11

John T. Trowbridge, The South: A Tour of Its Battle-Fields and Ruined Cities (New York:

Arno Press, 1969 [1866]), p. 573; Throckmorton quoted in Eric Foner, Nothing But Freedom:

Emancipation and Its Legacy (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981), p. 49.

12

Brig Gen D. Tillson to Capt W. T. Clarke, 18 Aug 1865 (T–54) (“Many freed”), NA T142, roll 27;

Brig Gen N. A. M. Dudley to Capt W. T. Clarke, 30 Sep 1865 (D–66) (“quite a large”), NA T142, roll 25.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

463

corn. “The cotton . . . elicits the praise of every body, and old planters say it is as ne

a crop as was ever produced on the farm.” Free labor seemed successful where former

slaves had been allowed self-direction in their work, but one inspector’s report could

not have been expected to budge the deeply ingrained prejudices of so many white

Southerners and Northerners alike.

13

In the summer of 1865, with the year’s crops still growing and the efcacy of free

labor still unproven, Southern planters clung stubbornly to old beliefs. As a captain

of the 113th USCI reported from Monticello, Arkansas, “many of the rebels do not

conceed that the ‘negro’ is yet free.” Similar reports came from all over the South.

A chaplain at Beaufort, South Carolina, told the department commander that local

planters viewed the Emancipation Proclamation as a wartime measure that had lapsed

with the Confederate surrender. West of the Appalachians, although Union soldiers

had occupied parts of Tennessee for more than three years, a captain of the 83d USCI

reported that “slavery, or the next thing to it,” was widespread. At Helena, Arkansas,

which federal troops had also held since 1862, Capt. Henry Sweeney of the 60th USCI

offered an even gloomier view. Black Mississippians who brought complaints to his

ofce, he told the assistant commissioner for that state, said “that there was nothing in

the worst days of slavery to compare with the present persecutions.”

14

Indeed, white Southerners bent every effort to impose a new social and economic

order that resembled the old as closely as possible. President Johnson’s provisional

governors called state conventions to repudiate secession and slavery, but the elections

that followed relied on voter qualications that had been in force before the war, when

all voters had been white men and most of them secessionist. The results were not

surprising. When the new Mississippi legislature convened in October, its members

quickly passed a set of laws to govern black residents that together became known

as the Black Code. The principal law bore the title “An Act to confer Civil Rights on

Freedmen,” but most of its sections limited, rather than conferred, any rights that for-

mer slaves hoped to enjoy. First among these was the prohibition of freedmen leasing

or renting farmland. This measure forced the overwhelming majority of former slaves,

who were too poor to own their own land, to work on the large farms and plantations

that were then being returned to possession of their former owners by the president’s

program of amnesty and individual pardon.

15

The Mississippi legislature also decreed that former slaves had to obtain

proof of residence and occupation in the form of annual contracts for farm la-

borers or licenses for self-employed workers. Other laws dened vagrancy so as

13

Lt Col D. H. Williams to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 18 Sep 1865 (W–4), NA M752, roll 22;

Nathan C. Hughes and Roy P. Stonesifer, The Life and Wars of Gideon J. Pillow (Chapel Hill:

University of North Carolina Press, 1993), pp. 142–43; Ira Berlin et al., eds., The Wartime Genesis

of Free Labor: The Lower South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 622–50; Hahn

et al., Land and Labor, pp. 681–96.

14

Barker quoted in Maj W. G. Sargent to Capt G. E. Dayton, 31 Aug 1865, NA Microlm Pub

M979, Rcds of the Asst Commissioner for the State of Arkansas, BRFAL, roll 23; Capt H. Sweeney to

Col S. Thomas, 11 Sep 1865, NA M979, roll 6; Chaplain M. French to Maj Gen Q. A. Gillmore, 6 Jun

1865, Entry 4109, Dept of the South, LR, pt. 1, Geographical Divs and Depts, RG 393, Rcds of U.S.

Army Continental Cmds, NA; Capt R. J. Hinton to “General,” 8 Sep 1865 (H–90), NA T142, roll 26.

15

William C. Harris, Presidential Reconstruction in Mississippi (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 1967), pp. 130–31; Edward McPherson, ed., The Political History of the United

States of America During the Period of Reconstruction (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972 [1871]),

p. 81.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

464

to limit the mobility of black laborers and consigned black orphans and some

other children to unpaid labor, euphemistically called apprenticeship, until a

girl’s eighteenth birthday or a boy’s twenty-rst. Yet another forbade black civil-

ians from possessing “re-arms of any kind, or any ammunition, dirk, or bowie-

knife.” The penalties were forfeiture of the weapon and a ten-dollar ne. Local

companies of the state militia, largely composed of Confederate veterans, began

enforcing the law. Black people were alarmed. “They talk of taking the armes

a way from (col) people and arresting them and put[ting] them on farms next

month,” Pvt. Calvin Holly of the 5th United States Colored Artillery (USCA)

wrote directly to General Howard from his post at Vicksburg. “They are doing

all they can to prevent free labor, and reestablish a kind of secondary slavery.”

16

Still other Mississippi legislation governed the testimony of black witnesses,

limiting their competence to cases that involved at least one black party. During

the fall and winter, legislatures of other Southern states enacted similar laws.

South Carolina charged black shopkeepers one hundred dollars for an annual

license. The most sobering feature of these laws was that they were not drafted

by ignorant rabble-rousers but by some of the most respected jurists in the South.

They reected the opinion of the most educated and well-to-do white men.

17

The passage of laws by state legislatures was no business of the Army’s.

What concerned federal occupiers was the preservation of public order, for much

of the South continued under martial law until President Johnson declared the

rebellion at an end on 2 April 1866. Even then, General Howard received instruc-

tions that the Freedmen’s Bureau might resort to military tribunals “in any case

where justice [could not] be attained through the medium of civil authority.” The

disorders that concerned the Army were violent for the most part and fell into

several broad categories: those that occurred between white plantation owners

and black laborers; rowdy misbehavior, when individual whites bullied freed-

people, or attempted to; and, nally, the kind of violence for which the South

became notorious, organized bands of night riders whose purpose was to terror-

ize the black population into subservience. To counter this violence, those black

regiments that were not guarding federal property or fortications moved detach-

ments of one or two companies into scattered county seats across the South. As

a staff ofcer at Shreveport, Louisiana, told the commanding ofcer of the 61st

USCI, the purpose of the troops was “to keep the country quiet, arrest criminals,

protect the weak and defenceless from wrong and outrage, and generally to en-

force obedience to the laws and orders.”

18

The relationship of plantation owners to their workers had become that of

employers to employees rather than that of masters to slaves, but planters were

slow to adapt to changed circumstances. They had “the idea rmly xed in their

minds that the negroes will not work[,] are impatient with them, and see no

16

McPherson, Political History, pp. 29–32 (“re-arms,” p. 32); Holly quoted in Ira Berlin et al.,

eds., The Black Military Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 755–56.

17

McPherson, Political History, pp. 31, 36; Carter, When the War Was Over, pp. 187–92; Foner,

Nothing But Freedom, pp. 49–53; Richard Zuczek, State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South

Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), pp. 15–16.

18

Capt B. F. Monroe to Colonel [Lt Col J. Foley], 24 Jul 1865, 61st USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94,

NA; McPherson, Political History, pp. 13–17 (“in any case,” p. 17).

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

465

way to induce faithfulness but by a resort to there old usages—the lash,” Maj.

George D. Reynolds of the 6th USCA reported from Natchez. Near Vicksburg,

the colonel of the 64th USCI wrote, “old masters . . . would abuse and shoot their

[former] slaves on the slightest provocation.” Since black laborers no longer rep-

resented a substantial capital investment, some plantation owners inicted whip-

pings more severe than those they had laid on before emancipation.

19

Although Bureau agents tried to investigate as many reports of wrongdoing

as they could, black soldiers sometimes took matters into their own hands. Near

Columbia, Louisiana, where “the cruel punishment of all colored people [was]

indulged in to the heart’s content” of white residents, Col. Alonzo W. Webber

reported, men of the 51st USCI threatened the life of a former slaveholder who

had “shot and killed one of his negroes.” The man’s former slaves had reportedly

told the soldiers about the incident and urged them to act. White residents were

“making a great howl over” the incident, the ofcer reported, for although they

“believe[d] it to have been originated by their own slaves,” they wanted a docu-

mented disturbance as a means of getting rid of a Union garrison in their midst,

especially one made up of black soldiers.

20

Incidents of fraud were also common. In North Carolina, Chaplain Henry M.

Turner of the 1st USCI told readers of the Christian Recorder that “freedmen . . .

have been kept at work until the crops were gathered, under the promise of pay or

part of the crop, but when the time for reward came, they were driven away, with-

out means, shelter or homes.” Many freedmen and their families gravitated to

Raleigh, the state capital, where they came under the care of Brig. Gen. Eliphalet

Whittlesey, former colonel of the 46th USCI, who was serving as assistant com-

missioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

21

While labor relations gave rise to a great deal of violence during the months

just after the Confederate surrender, any encounter between persons of different

races could spark an incident. An Army uniform was no guarantee of immunity

from an attack; rather, it might provoke one if the soldiers were few in number.

An ofcial inquiry into a street affray in Vicksburg elicited this statement from

one of the participants, Pvt. Berry Brown of the 5th USCA:

I was coming a cross the road . . . and three white men were going along the

road, one of them was ahead of the other two. And as I crossed the road he triped

me up. I then got up and asked him what he ment by triping a person up when

he was not medling with him. He then said you god dam black yankee son of

a bitch I will cut your dam guts out, and drew out his knife. . . . The orderly

Sergeant then came down to see what the fuss was about when he commenced

cuting at the orderly Sergeant. One of the boys then knocked him down with

19

Maj G. D. Reynolds to 1st Lt S. Eldridge, 31 Aug 1865, NA Microlm Pub M1907, Rcds of the

Field Ofces for the State of Mississippi, BRFAL, roll 34; Col S. Thomas to Maj Gen O. O. Howard,

12 Oct 1865, NA M752, roll 22; Hahn et al., Land and Labor, pp. 40–41, 80–81.

20

Col A. W. Webber to Capt S. B. Ferguson, 12 Sep 1865 (L–270–DL–1865), Entry 1757, Dept

of the Gulf, LR, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Hahn et al., Land and Labor, p. 165 (“the cruel punishment”).

21

Christian Recorder, 2 September 1865.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

466

a brick, and he got up and came after me again, and then I knocked him down

with a brick.

The investigator concluded, “I shall endeavor to teach the inlisted men . . . to avoid

if possible difculty with citizens, yet I will at the same time teach them never to

do so at the expense of their dignity and mand-hood and to disgrace the uniform

they wear.” Although such attacks made up only a small part of the violence di-

rected against freedmen, they became more frequent in the last months of 1865.

In December, reports appeared of black soldiers shot dead by white civilians at

Atlanta and in Calhoun and Hinds Counties, Mississippi.

22

Besides white Southerners, another group that was often hostile to black sol-

diers and civilians was the body of white federal troops in the South. Most of

these men did not differ in their attitudes from the unfavorable national consensus

regarding black people, and they often used their authority as members of the

occupying force to annoy and injure black civilians and, at times, the black men

who were their own comrades in arms. One such incident occurred in Washington,

D.C., in October 1865. The 107th USCI had just arrived from North Carolina to

take up garrison duties around the capital and pitched its tents near the Soldier’s

Rest, a transit camp at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad depot, near the Capitol.

On the morning of 14 October, 3 ofcers and 1,576 enlisted men of the 6th U.S.

Cavalry arrived, having just turned in their horses before taking ship for Texas.

The ofcers quickly “left for points ‘up town,’” the quartermaster in charge of

the Soldier’s Rest learned, presumably in search of amusement. Within hours, “a

difculty occurred . . . followed by blows, showers of stones and one gun shot”

that killed a soldier of the 107th. Authorities summoned ve other regiments to

the scene before the riot subsided. Similar conicts occurred in Charleston, South

Carolina, and in other cities where black and white soldiers with too few ofcers

and too much time on their hands encountered each other.

23

Most of the violence directed against black people in the South came on im-

pulse from individual whites. According to one count of more than fteen hundred

attacks on black Texans during the years from 1865 to 1868, nearly 70 percent

were individual acts. The unpredictable nature of such violence made it all the

more intimidating, but what drew national attention to the campaign to subjugate

the freedmen was its most distinctive feature: groups of men who rode disguised,

22

Maj D. Conwell to Capt R. Wilson, 20 Dec 1865 (quotations verbatim), 5th USCA, Regimental

Books, RG 94, NA; Lt Col G. Curkendall to Brig Gen D. Tillson, 26 Dec 1865 (G–18–1866), NA

M752, roll 20; Maj Gen M. F. Force to Maj M. P. Bestow, 12 Dec 1865 (F–226–MDT–1865), Entry

926, Dept of the Cumberland, LR, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Lt Col M. H. Tuttle to 1st Lt W. H. Williams,

21 Dec 1865, 50th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA; Joe G. Taylor, Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863–

1877 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974), p. 421.

23

Capt W. W. Rogers to Capt A. H. Wands, 15 Oct 1865 (R–655–DW–1865); Capt E. M. Camp

to Colonel Taylor [Col J. H. Taylor], 17 Oct 1865 (quotations), led with (f/w) RG–655–DW–1865;

Brig Gen F. T. Dent to General [Brig Gen A. V. Kautz], 14 Oct 1865; all in Entry 5382, Dept of

Washington, LR, pt. 1, RG 393, NA. 6th U.S. Cavalry return, Oct 1865, NA Microlm Pub M744,

Returns from Regular Army Cav Rgts, roll 61; Mark L. Bradley, Bluecoats and Tarheels: Soldiers

and Civilians in Reconstruction North Carolina (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009),

pp. 66–67, 123–24; Robert J. Zalimas, “A Disturbance in the City: Black and White Soldiers in

Postwar Charleston,” in Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era, ed.

John David Smith (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), pp. 361–90.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

467

often at night. These local bands, often called “regulators,” did not belong to the

Ku Klux Klan—the Klan’s founding meeting did not come until the spring of

1866, and its popularity did not sweep the South until after the last black volunteer

regiments had mustered out—but their aims and methods were those adopted later

by the Klan, and many of the participants must have joined the new organization.

The Klan may have begun as a social group of fun-loving young men in Pulaski,

Tennessee, but racial concerns were inevitably uppermost in its members’ minds,

so their club was not long in adopting the program of race warfare that had begun

almost as soon as Confederate armies surrendered.

24

Terrorism directed against black Southerners grew naturally out of the lawless-

ness that prevailed during the dying weeks of the Confederacy. Away from towns

occupied by the armies of either side, bands of “guerrillas and stray robbers and

thieves,” as one Union general called the forces of disorder, thrived. Near Mor-

24

Allen W. Trelease, White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction

(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971), pp. 3–21; Barry Crouch, The Dance of

Freedom: Texas African Americans During Reconstruction (Austin: University of Texas Press,

2007), pp. 95–117, esp. pp. 100–102; Paul A. Cimbala, Under the Guardianship of the Nation: The

Freedmen’s Bureau and the Reconstruction of Georgia, 1865–1870 (Athens: University of Georgia

Press, 1997), p. 204.

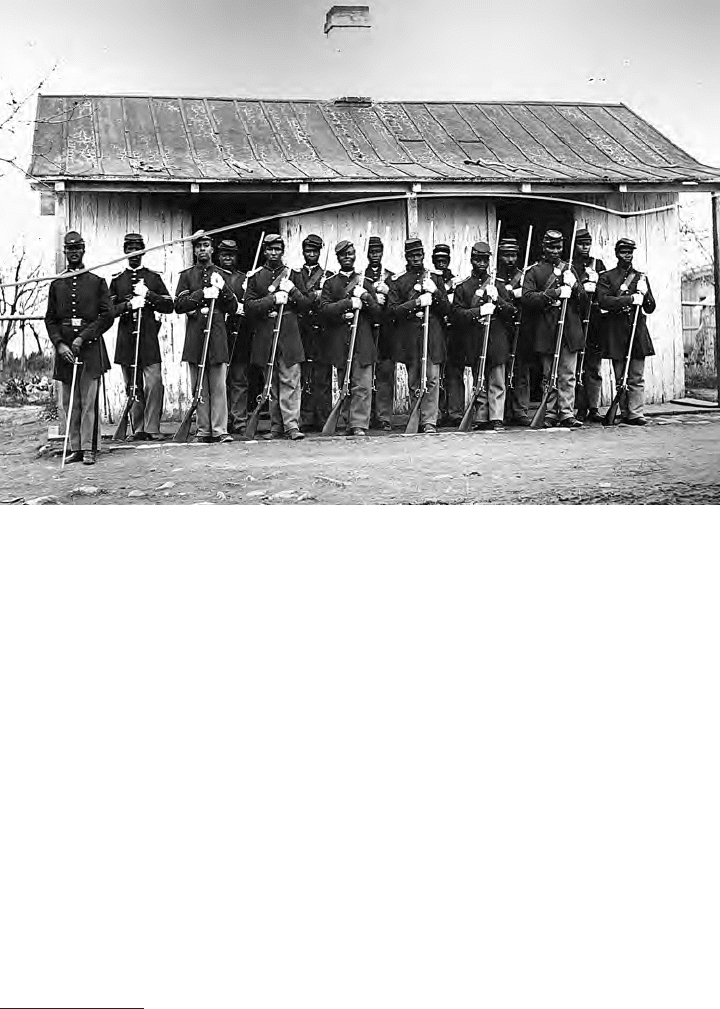

The 107th U.S. Colored Infantry served in Virginia and North Carolina before spending

its last year, 1865–1866, guarding ordnance stores and other public property around

Washington, D.C. In this cracked image, men of the regiment form in front of the

guardhouse at Fort Corcoran, across the Potomac from Georgetown.

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

468

ganza, Louisiana, the opposing sides arranged an armistice in the spring of 1865

“to enable the rebs to catch and hang a band of outlaws who infest the woods near

our lines, re into steamboats, [and] plunder citizens,” 2d Lt. Duren F. Kelley of

the 67th USCI wrote to his wife. “The rebs caught four of them day before yester-

day and hung them on a tree. They got ten yesterday and I don’t know how many

they have got today. They are hanged as fast as captured.” After surrenders across

the South, disbanded soldiers on their way home added to the confusion. When

Confederate troops in North Carolina laid down their arms that April, “most of

[the] cavalry refused to surrender,” the Union general commanding the Department

of the South reported. He predicted that “they will scatter themselves over South

Carolina and Georgia & commit all sorts of depredations, particularly upon the

colored people.”

25

Union occupation authorities inclined at rst to blame disbanded Confederate

soldiers for the unrest that roiled the South. The commanding ofcer of the 75th

USCI, for one, noted “large numbers of armed men of the late rebel army roaming

about” near Washington, Louisiana. Fifty miles to the east, a captain of the 65th

USCI serving as provost marshal at Port Hudson drew up charges for the military

trial of a Confederate veteran who had been robbing and killing freedmen nearby.

Maj. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus at Jackson, Mississippi, thought that the maraud-

ers’ abundant stock of military arms proved conclusively that they were “Rebel

soldiers.”

26

It was not long, though, before the occupiers began to detect other inuences

at work. Maj. Gen. Rufus Saxton, whose dealings with freedmen and their affairs

went back to the spring of 1862, reported in June that “guerrillas” around Augusta,

Georgia, included “young men of the rst families in the State, . . . bound together

by an oath to take the life of every able bodied negro man found off his plantation.”

Two months later, a lieutenant of the 4th United States Colored Cavalry (USCC)

told the ofcer commanding at Morganza, Louisiana, about “a secret society” of

Confederate veterans in a nearby parish “organized . . . to drive out or kill all per-

sons whom they term Yankees.” Americans’ well-known fascination with secret

societies suited perfectly the requirements of resistance to Reconstruction. Many

terrorists did not disguise themselves with masks or white sheets. A few simply

blackened their faces, donned cast-off Union uniforms, and told their victims that

they were U.S. Colored Troops. It was impossible for civil authorities to try them,

a district judge told the assistant commissioner, for the offenders “are unknown to

25

OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt. 3, p. 64 (“guerrillas”); Richard S. Offenberg and Robert R. Parsonage,

eds., The War Letters of Duren F. Kelley, 1862–1865 (New York: Pageant Press, 1967), p. 153. For

ofcial correspondence about outlaws and guerrillas in North Carolina, see OR, ser. 1, vol. 47, pt.

3, pp. 502, 543–45, 587; in Kansas, Mississippi, and Missouri, vol. 48, pt. 2, pp. 46, 346, 355–56,

571–72; in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee, vol. 49, pt. 2, pp. 418–19, 504, 1256–57.

Maj Gen Q. A. Gillmore to Adj Gen, 7 May 1865 (S–1077–AGO–1865), NA Microlm Pub M619,

LR by the Adjutant General’s Ofce, 1861–1870, roll 410. A good, brief synopsis of lawlessness

throughout the South in 1865 is Stephen V. Ash, When the Yankees Came: Conict and Chaos in the

Occupied South, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), pp. 203–11.

26

Lt Col J. L. Rice to Capt B. B. Campbell, 7 Jun 1865, 75th USCI, Entry 57C, RG 94, NA; Capt

A. D. Bailie to T. Conway, 30 Jul 1865 (B–36), and Charges and Specications, 1 Aug 1865 (B–39),

both in NA Microlm Pub M1027, Rcds of the Asst Commissioner for the State of Louisiana,

BRFAL, roll 7; Maj Gen P. J. Osterhaus to Capt J. W. Miller, 19 Aug 1865 (M–345–DM–1865),

Entry 2433, Dept of Mississippi, LR, pt. 1, RG 393, NA.

Reconstruction, 1865–1867

469

us except through negro testimony,” which was not admissible in court, “and we

cannot therefore punish them.” Before legislatures met that fall to revise the laws,

Southern states limited severely the competence of black witnesses, if they did not

rule out their testimony altogether.

27

White Southerners had a strong aversion to federal occupiers in general and

to black soldiers in particular, for the latter represented not simply military defeat,

but the beginning of a social revolution. “The negroes congregate around the garri-

sons, and are idle and perpetrate crimes,” the governor of Mississippi told General

Howard. “It is hoped the black troops will be speedily removed.” The governor an-

ticipated “a general revolt” of the freedmen, which he thought black troops would

support. From Clarksville, Tennessee, a state Supreme Court justice complained

to Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas about the 101st USCI stationed there. The regi-

ment’s commanding ofcer, the judge said, “regards himself as the guardian of the

negroes and this necessarily makes them insolent. . . . If the colored soldiers were

removed, the negro population would be more obedient to the laws.” It seemed

clear that the former rulers of the South intended “to accomplish by state legisla-

tion and by covert violation of law what they . . . failed to accomplish by Rebel-

lion,” the assistant commissioner for Missouri and Arkansas wrote. As a Bureau

ofcial in Tallahassee put it, white Floridians expected that after state conventions

met in the fall, “military forces will be withdrawn & the negroes will be again in

their power, to do with as they may see t.”

28

Unfortunately for the efcacy of the military occupation and the reputation of

the black regiments, there was a kernel of truth in some of the complaints about the

troops’ conduct. Like soldiers after other wars, veterans of the Civil War tended to

become unruly with the onset of peace. In one instance, the general commanding

in Alabama during the summer of 1865 had to ask that disaffected white regiments

of the XVI Corps be mustered out quickly and replaced by “troops that can be

depended on.” Two months later, an ofcer at Vicksburg placed an extra guard on

railroad yards to prevent looting by homeward-bound troops. In Georgia, a Bureau

ofcial reported that “the worst acts committed . . . upon negroes [near Augusta]

have been committed by . . . white soldiers.”

29

With time on their hands, black soldiers also misbehaved. A freedman showed

the Bureau agent at Helena his wounded scalp, cut by a brick in the hand of a sol-

dier of the 56th USCI during a street brawl. Along the river between Savannah and

27

Maj Gen R. Saxton to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 4 Jun 1865 (S–14) (“guerrillas”), NA M752,

roll 17; N. M. Reeve to Brig Gen D. Tillson, 27 Nov 1865 (“are unknown”), f/w Brig Gen D. Tillson

to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 28 Nov 1865 (G–37), NA M752, roll 20; 1st Lt J. W. Evarts to 1st Lt L. B.

Jenks, 22 Aug 1865 (f/w F–97–DL–1865), Entry 1757, pt. 1, RG 393, NA. On terrorists in blackface,

see Maj J. M. Bowler to Capt C. E. Howe, 15 Oct 1865, Entry 269, Dept of Arkansas, LR, pt. 1, RG

393, NA; Maj J. M. Bowler to Maj W. S. Sargent, 31 Oct 1865, NA M979, roll 23; Cimbala, Under

the Guardianship, p. 204.

28

W. L. Sharkey to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 10 Oct 1865 (M–45), NA M752, roll 22; J. O.

Shackelford to Maj Gen G. H. Thomas, 18 Jul 1865 (S–18), NA T142, roll 27; Brig Gen J. W. Sprague

to Maj Gen O. O. Howard, 17 Jul 1865 (“to accomplish”), NA M979, roll 23; Col T. W. Osborn to Maj

Gen O. O. Howard, 21 Sep 1865 (F–4) (“military forces”), NA M752, roll 20.

29

Maj Gen C. R. Woods to Brig Gen W. D. Whipple, 20 Sep 1865 (A–443–MDT–1865), Entry

926, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Maj E. B. Meatyard to 1st Lt C. W. Snyder, 10 Nov 1865, (M–394–DM–

1865), Entry 2433, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; Brig Gen E. A. Wild to Maj Gen R. Saxton, 14 Jul 1865, NA

Microlm Pub M869, Rcds of the Asst Commissioner for the State of South Carolina, BRFAL,

Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867

470

Augusta, Georgia, men of the 33d USCI looted houses. Thefts from garden plots

near Brookhaven and Vicksburg, Mississippi, became frequent as soldiers of the

58th and 108th USCIs tried to supplement the inadequate Army ration. An ofcer

at Brookhaven recognized the connection. “It is absolutely necessary in order to

maintain discipline, and prevent depredation,” he urged, “that supplies should be

forwarded more regularly.” Neither black nor white civilians were exempt from

pillage. In Nashville, a black street vendor complained to the Bureau that men

of the 15th USCI “forceably took from him watermelons” valued at twenty-one

dollars. A lieutenant of the 101st USCI serving as Freedmen’s Bureau agent at

Gallatin, Tennessee, wrote to the assistant commissioner to request the removal of

one company from his own regiment and the assignment of another to the garrison

there. The discipline of the company he wanted removed was so lax, he explained,

“that it is utterly impossible to have them perform their various duties correctly.

When they are sent on duty away from the Post, they cannot be depended upon.

Their lawless acts are becoming a disgrace to the public service.”

30

While black soldiers used their off-duty hours to supplement their diet,

often at the expense of black and white civilians, they also helped neighboring

freedpeople adjust to their new status, both with advice and in more substantial

ways. At Helena, Arkansas, men of the 56th USCI cleared ground and erected

buildings for an orphanage; at Okolona, Mississippi, black civilians elected two

noncommissioned ofcers of the 108th USCI as their nancial agents in starting

a school. Enlisted men and ofcers of the 62d and 65th USCIs—originally

the 1st and 2d Missouri Infantries (African Descent)—raised $5,346 toward

the founding of the Lincoln Institute, the forerunner of Lincoln University, in

Jefferson City.

31

The shortage of ofcers in the black regiments was one reason for a lack

of discipline that many observers noticed. This problem became apparent as

soon as the ghting died down and the troops took up occupation duties. Even

before the Freedmen’s Bureau organized fully, an inspector at New Orleans

warned that “a large number of ofcers” of the 81st USCI “have been detached

and placed on duties in this city,” in addition to ve assigned to various staff

jobs at Port Hudson. “The 81st is a very ne regiment,” he wrote, “and should

have the requisite number of ofcers to maintain its present reputation by con-

stant attention.” Three days after the inspector’s warning, a general in Louisi-

roll 34. Instances of misbehavior by troops of another American occupying force are in Earl F.

Ziemke, The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944–1946, U.S. Army in World War II

(Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1975), pp. 323–25, 421–23.

30

Capt H. Sweeney to 1st Lt S. J. Clark, 13 Jul 1865, 56th USCI; Maj L. Raynolds to 1st Lt J.

A. Stevens, 6 Sep 1865, 58th USCI; 1st Lt C. Wright to Commanding Ofcer (CO), 108th USCI, 10

Jul 1865, and 2d Lt A. F. Cook to CO, 108th USCI, 30 Aug 1865, both in 108th USCI; Endorsement,

Lt Col N. S. Gilson, 21 Sep 1865, on Maj L. Raynolds to Lt Col J. W. Miller, 19 Sep 1865 (R–137–

DM–1865), 58th USCI; all in Entry 57C, RG 94, NA. 1st Lt A. J. Harding to Col R. W. Barnard, 16

Aug 1865 (“forceably took”), NA T142, roll 27; Brig Gen E. L. Molineux to Maj W. L. M. Burger, 22

Jun 1865, Entry 4109, Dept of the South, LR, pt. 1, RG 393, NA; 1st Lt A. L. Hawkins to Brig Gen

C. B. Fisk, 2 Sep 1865 (H–102 1/2) (“that it is”), NA T142, roll 26.

31

1st Lt S. J. Clark to J. Dickenson and T. Harrison, 11 Jun 1866, 56th USCI, Regimental Books,

RG 94, NA; HQ 108th USCI, Regimental Order 137, 25 Oct 1865, 108th USCI, Regimental Books, RG

94, NA; W. Sherman Savage, The History of Lincoln University (Jefferson City, Mo.: Lincoln University,

1939), pp. 2–3.