Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

84

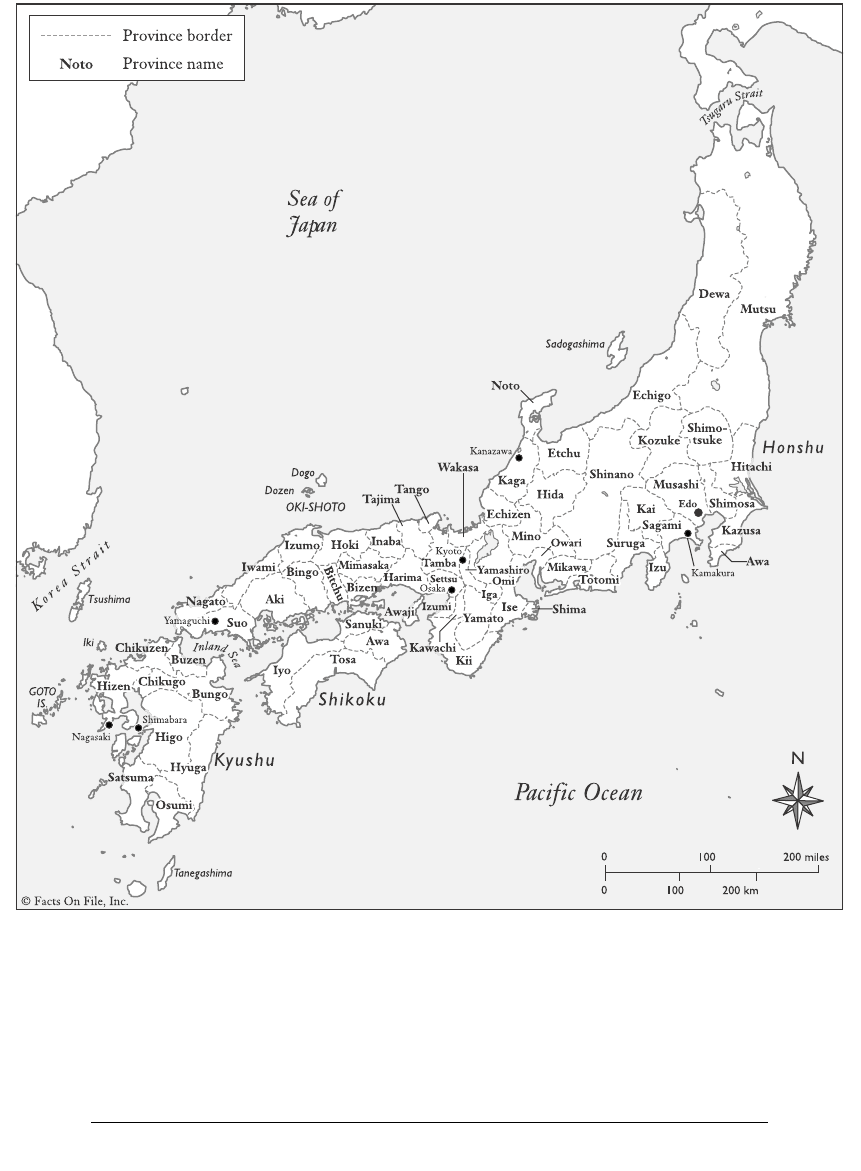

Map 3. Provinces of Medieval and Early Modern Japan

L AND, ENVIRONMENT, AND P OPULATION

85

READING

Landscape and Environment

Trewartha 1965: geography and environment; Asso-

ciation of Japanese Geographers (eds.) 1980: geog-

raphy and environment; Totman 1993, 3–10:

geography and climate; Totman 2000, 11–19: geog-

raphy, climate, and flora and fauna, 248–252: natural

resources in the early modern period; Miner, Oda-

giri, and Morrell 1985, 415–418: geography, flora

and fauna, 430–433: list of important bodies of

water, mountains, and islands with their locations,

433–441: poetic place names

City, Town, and

Countryside

Beasley 1999, 161–170: cities, towns, and country-

side; Totman 1993, xvii: map of castle towns, 11–15:

countryside, 25–28: cities and towns; Totman 1981,

189–1992: city, countryside, and social change;

Frédéric 1972, 90–112: cities in the medieval period,

113–137: the countryside in the medieval period;

Totman 2000, 154–158: medieval urbanization,

236–241, 260–261: Kyoto and its culture in the early

modern period, 241–243: Osaka culture in the early

modern period, 243–245, 261–263: Edo culture in

the early modern period

Population Statistics

Hall (ed.) 1991, 519: population statistics; Totman

1993, 249–252: population statistics; Yonemoto

2003, 17: population statistics; Naito 2003, 178–179:

population and population density of Edo; Hanley

1997, 129–131: early modern demographics; Tot-

man 2000, 232–233, 247–248: early modern demo-

graphics, 261: population statistics

Regions, Provinces, and

Equivalent Modern

Prefectures

Miner, Odagiri, and Morrell 1985, 418–429:

provinces, prefectures, and maps

GOVERNMENT

3

IMPERIAL AND

MILITARY RULE

For the nearly 700-year span of Japan’s medieval

and early modern periods, warriors—with varying

levels of effectiveness and hegemony—ruled the

country. Although the fortunes of particular ex-

tended warrior families waxed and waned, only

members of the warrior class could serve as shoguns,

the military rulers. Their governments, known com-

monly as shogunates, were often challenged by the

interests of other powerful warrior families in vari-

ous parts of Japan and by the imperial family in

Kyoto.

Although the warrior bureaucracy largely con-

trolled the affairs of the state, the emperor and the

imperial court were still the formal head of govern-

ment. Warrior governments typically sought out—

or forced—the formal imperial decrees that gave

legitimacy to the shoguns. Occasionally emperors

would attempt to reassert direct imperial rule. They

were, however, always suppressed in favor of warrior

rule. During the first part of the Kamakura period,

the shogunate and the court more or less shared

governmental authority. By the middle of the

medieval period and into the early modern period,

court power and authority became mostly a thing of

the past.

Warrior governments functioned as a lord-vassal

system of loyalty. This is reflected in the political

structures of the different shogunates. Although

they varied greatly in their organization, the notion

of loyalty, whether earned or forced, always laid the

foundation on which the warrior government was

built.

During the earlier Nara and Heian periods, the

kuge—members of the imperial court and powerful

aristocratic families—controlled Japan. With the

rise of the warrior class from the Kamakura period,

however, this power was eclipsed but never replaced

or abolished.

The term tenno (literally, “heavenly sovereign,”

that is, the emperor) refers to Japanese sovereigns

and dates back to at least the seventh century. Impe-

rial descent was traced through a hereditary line,

usually through males, although examples do exist of

female rulers. Early in Japan’s history, the emperor

served both secular and religious roles. By the start

of the medieval period, however, warriors largely

eclipsed imperial authority. Emperors therefore

took on a mostly ceremonial or symbolic role in the

centuries that comprise Japan’s medieval and early

modern periods.

When Minamoto no Yoritomo established the

Kamakura shogunate in 1185, he chose to maintain

his base of operations at Kamakura, the location of

the family in eastern Japan. The court stayed at

Kyoto. The imperial court became an organ of the

shogunate, used to appoint shoguns and for other

ceremonial occasions that served mostly to legiti-

mate warrior rule.

The shogunal regent (shikken) system put into

effect by the Hojo family further transformed the

relationship between court and shogunate. At court,

the imperial government was run, in fact, not by the

emperor but by an imperial regent from the aristo-

cratic Fujiwara family. The Hojo family was now in

control of the shogunate via the shogunal regency.

Both forms of authority were thus controlled by

regents, with the Hojo regent regulating most

aspects of government. The Hojo regents also

increasingly involved themselves in matters of impe-

rial succession, thereby lending additional complica-

tions to the already divisive process of choosing

emperors.

Interactions between court and shogunate also

included periodic power struggles. The 1221 Jokyu

Disturbance, in which the retired emperor Go-Toba

unsuccessfully attempted to overthrow the shogu-

nate, resulted in stricter control by the shogunate

over the court; it came to control imperial succession.

The Kemmu Restoration (1333–36), Emperor Go-

Daigo’s short-lived reestablishment of direct imperial

rule, is the most dramatic example of court-shogunate

conflict. Emperor Go-Daigo’s three-year usurpation

of power was overturned by Ashikaga Takauji, who

thereafter established the Ashikaga shogunate inau-

gurating the start of the Muromachi period.

The court not only struggled against the shogu-

nate, but it also, periodically, struggled against itself.

This was especially pronounced during the period of

the Northern and Southern Courts (1337–92). The

13th century witnessed two rival lines of imperial

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

88

succession that led, by the 14th century, to a nearly

60-year span of dual imperial courts. These two rival

lineages were the Jimyoin, descended from Go-

Fukakusa (89th emperor, r. 1246–59) and the Daika-

kuji, descended from Kameyama (90th emperor, r.

1259–74), Go-Fukakusa’s brother. Each brother vied

to gain total control from the other. To quell this

dispute, shogunal regent Hojo Sadatoki ruled that

each line would provide the emperor in an alternat-

ing succession. This ruling, known as the Bumpo

Compromise, required the emperor from each

throne to rule for 10 years and then abdicate so the

emperor from the other line could rule. The deci-

sion, however, only staved off the inevitable break

between the Jimyoin and Daikakuji lines. In 1331,

Emperor Go-Daigo, the 96th emperor, in the Dai-

kakuji line, attempted to cut the Jimyoin line out of

the imperial succession. The Jimyoin line, supported

by Hojo Takatoki, resisted. In the ensuing confu-

sion, Go-Daigo fled Kyoto with the imperial regalia

(shinki—mirror, sword, and jewel), symbols of impe-

rial authority and the legitimate right to rule.

The conflict led to the division into the Northern

and Southern Courts, which lasted from 1337 to

1392. The Northern Court (Hokucho) was situated

in Kyoto, while the Southern Court (Nancho) was

located in the south at Yoshino. The first five emper-

ors of the Northern Court—Kogon, Komyo, Suko,

Go-Kogon, and Go-En’yu—were considered ille-

gitimate tenno because they did not possess the

imperial regalia. The separation of the Northern

and Southern Courts continued for nearly 60 years

before the Southern Court relinquished their claims

of being the true imperial line.

At the end of the medieval period, the three

great unifiers of Japan, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi

Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu, each used the

title-granting authority of the imperial court to

accumulate titles that served to legitimate their rule.

Tokugawa Ieyasu obtained the status of shogun.

Subsequent Tokugawa shoguns provided for the

imperial line by restoring the imperial palace and

making income available to the imperial family. On

the other hand, the shogunate maintained control

over the court and aristocrats by enacting legal regula-

tions that set strict limits on their activities. As in the

medieval period, the emperor was largely a figurehead

whose main function was to perform public rituals.

Imperial fortunes dramatically changed toward

the end of the Edo period. The Tokugawa shogu-

nate faced increasing criticism regarding how it

both handled internal affairs and permitted increas-

ingly frequent interactions with Europeans, Ameri-

cans, and other foreign powers who urged Japan to

open its ports to foreign trade and, by extension,

cultural influence. In this atmosphere, the slogan

sonno joi, “revere the Emperor, expel the barbar-

ians,” became the rallying call of those who wanted

to overthrow the Tokugawa shoguns and restore

direct imperial rule. The result of this movement

was the dismantling of the Tokugawa shogunate

in 1868, and the inauguration of the Meiji Resto-

ration.

STRUCTURE OF THE

IMPERIAL COURT

The system of court ranks that organized the aristo-

cratic hierarchy during the medieval and early mod-

ern periods was derived from the system established

in the early eighth century, the Taiho Code, which

had been based on Chinese models. Ranks were con-

ferred on both aristocratic men and women. The sta-

tus awarded determined the types of government

positions one could hold and consequently one’s rela-

tive power within the aristocratic and imperial hierar-

chy. Rank therefore had a large impact on one’s social

standing, political power, and economic wealth.

Although occasionally making some allowance for

ability, the Japanese rank system was mostly based on

the prestige of one’s family background.

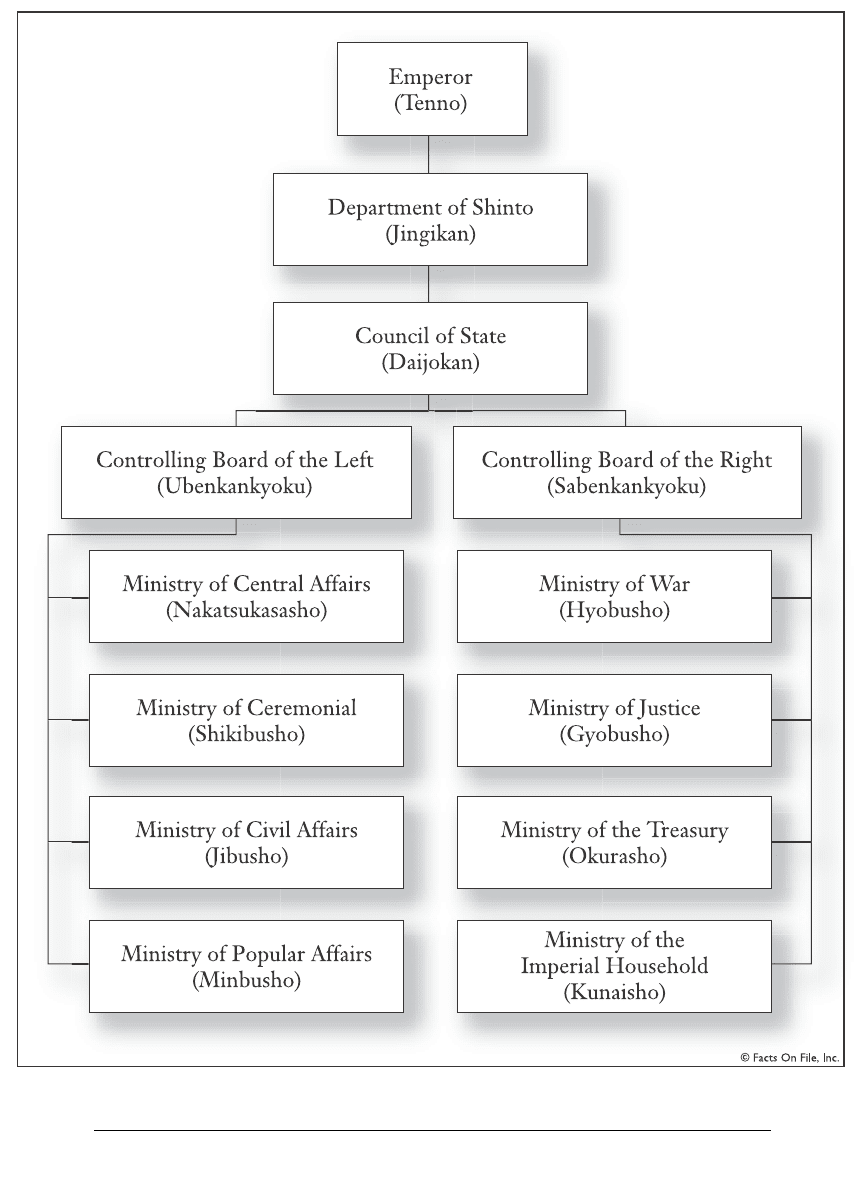

The structure of the imperial court was a com-

plex affair. The following chart depicts the basic

outline, but each division and ministry contained a

hierarchy of officials. Some divisions also included

subdivisions. Despite the formality of this structure,

the operation and functionality of any particular

ministry fluctuated depending on the particular time

period. There were also aristocratic families who

came to dominate a particular court function

through the use of heredity.

G OVERNMENT

89

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

90

Court Ranks

Ranks for imperial princes and government officials:

IMPERIAL PRINCES

First Order (ippon)

Second Order (nihon)

Third Order (sanbon)

Fourth Order (shihon)

PRINCES AND GOVERNMENT

OFFICIALS

Senior First Rank (shoichi-i)

Junior First Rank (juichi-i)

Senior Second Rank (shoni-i)

Junior Second Rank (juni-i)

Senior Third Rank (shosan-i)

Junior Third Rank (jusan-i)

Senior Fourth Rank, Upper Grade (shoshi-ijo)

Senior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade (shoshi-ige)

Junior Fourth Rank, Upper Grade (jushi-ijo)

Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade (jushi-ige)

Senior Fifth Rank, Upper Grade (shogo-ijo)

Senior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade (shogo-ige)

Junior Fifth Rank, Upper Grade (jugo-ijo)

Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade (jugo-ige)

GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS ONLY

Senior Sixth Rank, Upper Grade (shoroku-ijo)

Senior Sixth Rank, Lower Grade (shoroku-ige)

Junior Sixth Rank, Upper Grade (juroku-ijo)

Junior Sixth Rank, Lower Grade (juroku-ige)

Senior Seventh Rank, Upper Grade (shoshichi-ijo)

Senior Seventh Rank, Lower Grade (shoshichi-ige)

Junior Seventh Rank, Upper Grade (jushichi-ijo)

Junior Seventh Rank, Lower Grade (jushichi-ige)

Senior Eighth Rank, Upper Grade (shohachi-ijo)

Senior Eighth Rank, Lower Grade (shohachi-ige)

Junior Eighth Rank, Upper Grade (juhachi-ijo)

Junior Eighth Rank, Lower Grade (juhachi-ige)

Greater Initial Rank, Upper Grade (daisho-ijo)

Greater Initial Rank, Lower Grade (daisho-ige)

Lesser Initial Rank, Upper Grade (shosho-ijo)

Lesser Initial Rank, Lower Grade (shosho-ige)

LIST OF EMPERORS

Emperor Birth/ Reign

Death Dates

82 Go-Toba 1180–1239 1183–1198

83 Tsuchimikado 1195–1231 1198–1210

84 Juntoku 1197–1242 1210–1221

85 Chukyo 1218–1234 1221

86 Go-Horikawa 1212–1234 1221–1232

87 Shijo 1231–1242 1232–1242

88 Go-Saga 1220–1272 1242–1246

89 Go-Fukakusa 1243–1304 1246–1259

90 Kameyama 1249–1305 1259–1274

91 Go-Uda 1267–1324 1274–1287

92 Fushimi 1265–1317 1287–1298

93 Go-Fushimi 1288–1336 1298–1301

94 Go-Nijo 1285–1308 1301–1308

95 Hanazono 1297–1348 1308–1318

96 Go-Daigo 1288–1339 1318–1339

97 Go-Murakami 1328–1368 1339–1368

98 Chokei 1343–1394 1368–1383

99 Go-Kameyama 1347–1414 1383–1392

100 Go-Komatsu 1377–1433 1392–1412

101 Shoko 1401–1429 1412–1428

102 Go-Hanazono 1419–1470 1428–1464

103 Go-Tsuchimikado 1442–1501 1465–1500

104 Go-Kashiwabara 1464–1527 1500–1526

105 Go-Nara 1496–1558 1526–1557

106 Ogimachi 1517–1593 1557–1586

107 Go-Yozei 1571–1617 1586–1611

108 Go-Mizunoo 1596–1680 1611–1629

109 Meisho (f) 1623–1696 1629–1643

110 Go-Komyo 1633–1655 1643–1654

111 Gosai 1637–1685 1656–1663

112 Reigen 1654–1732 1663–1687

113 Higashiyama 1675–1710 1687–1709

114 Nakamikado 1701–1737 1710–1735

115 Sakuramachi 1720–1750 1735–1747

116 Momozono 1741–1763 1747–1762

117 Go-Sakuramachi 1740–1813 1763–1770

118 Go-Momozono 1758–1780 1770–1779

119 Kokaku 1771–1840 1780–1817

120 Ninko 1800–1846 1817–1846

121 Komei 1831–1866 1846–1866

G OVERNMENT

91

EMPERORS OF THE NORTHERN

COURT (1337–1392)

1 Kogon 1313–1364 r. 1332–1333

(Northern only)

2 Komyo 1321–1380 r. 1333–1348

(Northern only)

3 Suko 1334–1398 r. 1348–1351

(Northern only)

4 Go-Kogon 1338–1374 r. 1352–1371

(Northern only)

5 Go-En’yu 1358–1393 r. 1371–1382

(Northern only)

6 Go-Komatsu 1377–1433 r. 1382–1392

(Northern);

r. 1392–1412

(reunified)

STRUCTURE OF THE

SHOGUNATES

Kamakura Shogunate

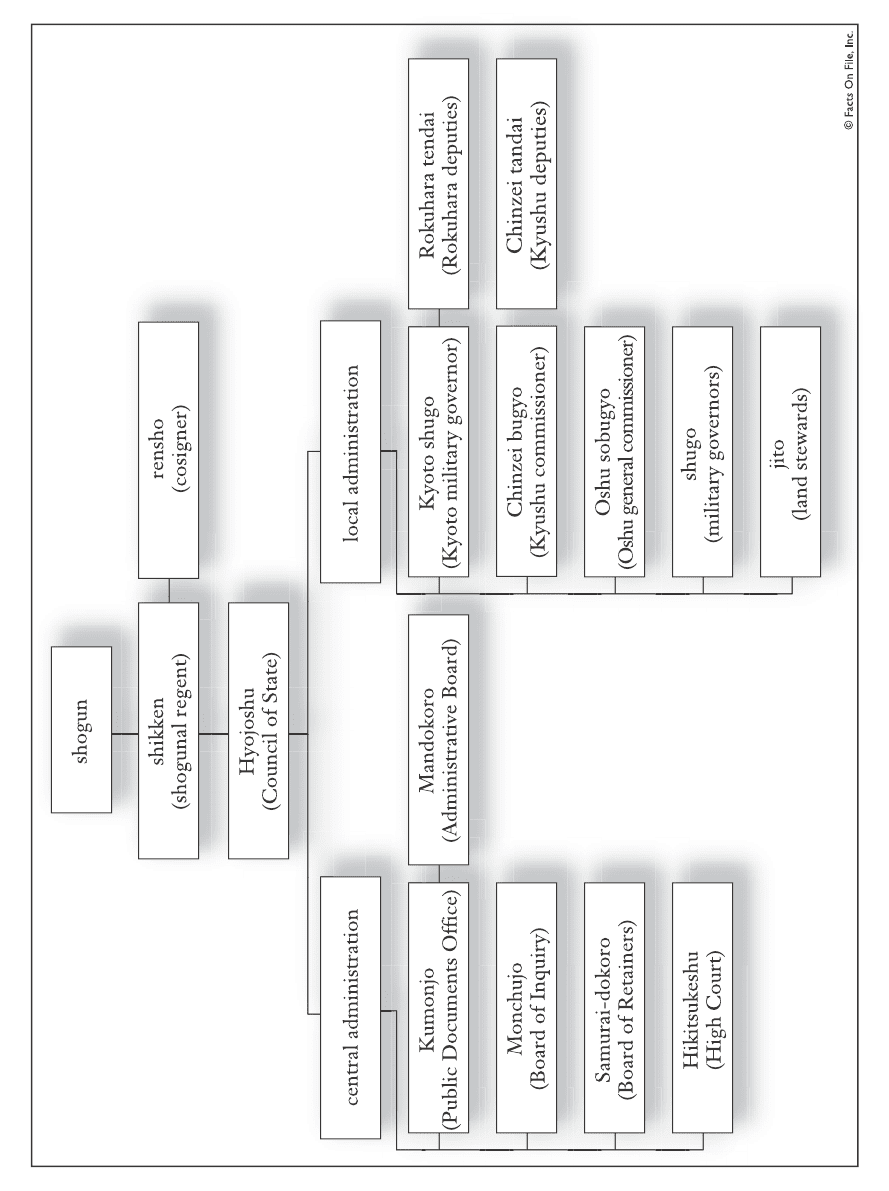

shikken (shogunal regent) The office of shogunal

regent was held by members of the Hojo family

between 1203, when Hojo Tokimasa assumed the

title, until the end of the Kamakura period in 1333.

Lacking the necessary social rank to hold the title of

shogun, it was through the office of shikken that the

Hojo family was able to run the government behind

the scene. As shogunal regents, the Hojo family not

only controlled the affairs of state, they eventually

came to decide who would be appointed shogun in

the first place.

rensho (cosigner) The office of rensho was estab-

lished by the shogunal regent Hojo Yasutoki in 1225

as a way to share power and government administra-

tion with competing branches of the Hojo family.

This position created, in effect, an associate regent.

Official documents required the signatures of both

the regent and the cosigner.

Hyojoshu (Council of State) The Hyojoshu was

established in 1225 by Hojo Yasutoki as a way to

share the responsibility for governance. The council

included the most important statesmen, warriors,

and scholars. Matters were decided by a simple

majority vote. It was the highest decision-making

body in the Kamakura government.

Kumonjo (Public Documents Office) The

Kumonjo was established by Minamoto no Yorito-

mo in 1184 as the main executive and general

administrative office of his government. After the

establishment of the Kamakura shogunate, this

office was renamed the Mandokoro.

Mandokoro (Administrative Board) Established

in 1191 by Minamoto no Yoritomo, the Mandokoro

took over the functions of the Kumonjo as the main

executive and general administrative office of the

Kamakura shogunate. After Hojo family regents

assumed real control over the shogunate, they trans-

formed the Mandokoro into an office whose sole

responsibility was to oversee the government’s

finances.

Monchujo (Board of Inquiry) In 1184 Minamoto

no Yoritomo established the Monchujo to be

responsible for legal matters, especially dealing with

lawsuits and appeals. Most cases concerned disputed

land rights, but over time they included such things

as business matters and loans.

Samurai-dokoro (Board of Retainers) This office

was established by Minamoto no Yoritomo in 1180.

It functioned as a disciplinary board to regulate the

activities of Yoritomo’s expanding network of war-

rior vassals (gokenin). Its main responsibility was

overseeing the police and the land stewards (jito). In

the Muromachi period, added duties included secu-

rity for the capital at Kyoto, and administration of

shogunal and other property.

Hikitsukeshu (High Court) The Hikitsuke was

established as a judicial court by shogunal regent

Hojo Tokiyori in 1249. It was intended to supple-

ment the responsibilities of the Hyojoshu (Council

of State). Among the legal issues dealt with by this

body were land claims and taxation.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

92