Canale L.C.F., Mesquita R.A., Totten G.E. Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a thin thickness that the liquid metal, even at the

appropriate temperature, cannot fill them com-

pletely.

The component that shows this kind of defect,

depending on the size and location of the joint,

must be discarded, since recovery with a weld is

not recommended from a metallurgical point of

view or, depending on the cost-benefit ratio,

is not justified. This defect is usually seen, but

can occur and be unnoticed initially, in compo-

nents with complex geometry and abrupt vari-

ation of mass, where it is used to obtain a large

number of cores that could provide details dif-

ficult to be observed by quality control. In these

cases, the defect will only be located when there

are cracks/disruption in heat treatment or leak-

age and fracture when the component is in

service.

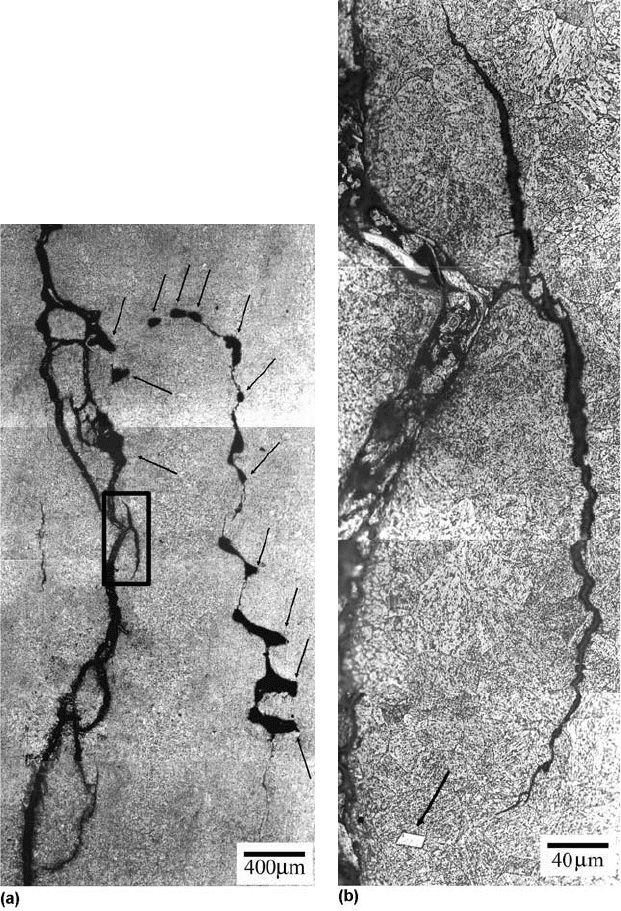

Fig. 21

(a) Micrograph showing cracks connecting shrinkage pores (indicated by arrows) in the internal component of the sample.

(b) Detail of the box in (a), where an inclusion is indicated by the arrow

164 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 164

In summary, to avoid the appearance of cold

joints in cast components, it is necessary to

control several man ufacturing stages of its

design; for example, prevent the component

from having regions with very thin thickness;

appropriate fusion and pouring temperatures for

each component; appropriate mold-filling

channel system; compatible pouring speed; and

well-established necessary amount of liquid

metal for filling the mold to avoid temporary

interruption in pouring.

Inclusions

Inclusions can be defined as nonmetallic and

sometimes intermetallic phases embedded in a

metallic matrix (Ref 16). Th ey are usually sim-

ple oxides, sulfides, or nitrides. In almost all

instances of metal casting, they are considered

to be detrimental to the performance of the cast

component. Sometimes, an intentional intro-

duction in larger quantities can lead to unique

dispersion-strengthened materials. There are

essentially two classifications for all inclusions:

Exogenous—those derived from external

causes

Indigenous—those that are native, innate,

or inherent in the molten metal treatment

process

Slag, dross, entrapped mold materials, and

refractories are examples of inclusions that

would be classified as exogenous. In most cases,

these inclusions are macroscopic or visible to

the naked eye at the casting surface. When the

casting is sectioned, they may also appear

beneath the external casting surface if they

have had insufficient time to float out or settle

due to the density differences with respect

to the molten metal. The presence of these

macroinclusions in steel castings is avoidable,

but their presence has plagued all forms of steel

casting and is particularly problematic in both

foundry processing and in the continuous cast-

ing of sheet steels and wire.

Macroinclusions are always practice related,

and analysis of the size and chemical composi-

tion of a macroinclusion can lead to the identi-

fication of potential sources of this problem.

Once an inclusi onal source is developed, a clear

and effective process change can be made to

eliminate such problems in the future. There-

fore, the techniques already developed by inte-

grated steel manufacturers can be readily

applied to foundries by coupling inclusion

identification with an in-dept h study of steel-

making and casting prac tices in the foundry.

Horwath and Goodrich (Ref 17) and Svoboda

et al. (Ref 18) have studied macroinclusions and

identified that these kind of inclusions can result

in excessive casting repairs or rejected castings.

To reduce these problems, a method was dev-

eloped to ensure that there are no inclusions in

cast materials above a size that results in failure

during ultrasonic or visual inspection of the

casting. In this method, the macroinclusions

should be eliminated; that is, inclusions greater

than 100 mm must be eliminated, but more

severely, inclusions greater that 50 mm should

be eliminated also.

Sulfides, nitrides, and oxides are examples of

indigenous inclusions that result from chemical

reactions of the molten metal and the local

environment. They are usually very small and

uniformly distributed inclusions, requiring

optical microscopy to visualize them. The pre-

sence of these microinclusions in castings is

generally unavoidable (Ref 9), because they

are the natural inclusions that are formed in

liquid steels due to the reaction between

alloying elements and oxygen; however, it is

necessary to minimize these inclusions as a

grain-boundary distribution of these inclusions

can be damaging to the component mechanical

properties.

Clean Steel

Clean steel is the common name attributed to

steel that has low levels of the elements sulfur,

phosphorus, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen, as

well as residual ele ments copper, lead, zinc,

nickel, chromium, bismuth, tin, antimony, and

magnesium and almost no oxide product defects

produced during the act of steelmaking, ladle

Fig. 22

Surface of a microfused component showing surface

decarburization

Failures from the Casting Process / 165

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 165

metallurgy, casting, and rolling. Because the

“clean” concept is not absolute, the clean-

liness standard desired by the customer is con-

tinuously changing as a function of time and

technological improvements. The term clean

steel is therefore continually variable, depend-

ing on the application and the competition

between steel suppliers.

Thus, due to the variability of the term clean,

it is typical to refer to high-purity steels as steels

with low levels of solutes, and low-residual

steels as steels with low levels of impurities. For

example, there are high-purity, low-residual

clean steels, such as ultra-deep-drawing steel

sheets for automobiles, that require ultralow

carbon contents (530 ppm), low nitrogen con-

tents (530 ppm), and the absence of oxide

inclusions with diameters greater than 100 mm;

and there are low-residual clean steels, such as

those used for drawn and ironed cans, that are a

standard low-carbon steel (1006) without high-

purity component requirements but are ultra-

clean, with the requirement that oxide diameters

must be less than 20 mm. In addition, in forging

and bearing grades, there are clean steels that

require strictly controlled inclusion size dis-

tributions.

The total inclusion content related to the total

oxygen content has been correlated with bearing

life, and decreasing total oxygen contents

(below 10 ppm) improve the bearing life. In

addition to total oxygen content, the total length

of stringer inclusions after forging is also related

to the bearing life, and, at low total oxygen

levels, efforts to reduce inclusion cluste ring lead

to very long fatigue life for bearings.

Clean steels can be classified as steels with a

low frequency of inclusions (55 mm). The

major problems in clean steel manufacture are

incomplete separation of clustered solid inclu-

sions (45 mm in diameter), the presence of

sporadic larger liquid inclusions due to emulsi-

fication of covering slags, and the presence of

solid materials that originate from the refrac-

tories used to contain steels . The equipment used

to produce clean steel varies greatly between

different steel plants; however, current clean

steelmaking and casting practices are based on

the following principles:

The oxygen dissolved in liquid steel at the

melting stage must be transformed into a

solid or a gas and removed before casting.

The external oxygen sources that are res-

ponsible for the reoxidation of liquid steel

must be eliminated at every step in the

process.

The physical entrapment of the liquid fluxes

used during steel refining and casting must

be eliminated.

Refractories in contact with liquid steel must

be chemically stable and resistant to corro-

sion and erosion.

These simple principles are based on the

importance of maint aining chemical equilibrium

between the elements dissolved in liquid steel

and the slag and refractory systems that are in

contact with the liquid steel. Additionally, it is

necessary to control the fluid flow to avoid

conditions at liquid slag-steel interfaces that

could result in the physical entrapment of the

covering slag.

Clean steel manufacture is dependent on an

understanding of the fundamental steps neces-

sary to produce a clean steel:

Generation of the inclusion

Transport of the inclusion to an interface

Separation of the inclusion at the interface

Removal of the inclusion from the interface

The production of really clean steel depends of

the correct application of these principles.

The Formation of Macroinclusions

There are four major methods of forming

macroinclusions, and all problems occur during

foundry processing:

Reoxidation

Interaction between liquid steel and liquid

slags: vortexing, ladle or mold filling, argon

stirring, and pouring through a slag layer

Erosion/corrosion during steel pouring

Inclusion agglomeration due to clogging

during steel pouring

Reoxidation. The major cause of macro-

inclusion formation in casting is reoxidation

(Ref 17–19). To understand reoxidation, it is

necessary to understand that liquid iron is not

thermodynamically stable in the presence of

oxygen. The spontaneous reaction that occurs

results in the formation of iron oxide. As deoxi-

dizers are added, the steel remains unstable in

the presence of oxygen as a gas, but now the

inclusions that form include the oxides of the

deoxidants. Some deoxidants, such as alumi-

num, magnesium, and calcium, form very stable

oxides that are more stable than some slag and

166 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 166

refractory chemistries. Thus, the steel reacts

with the less stable oxides. Reoxidation can

occur by reaction with:

The ambient atmosphere (air)

The slag components less stable than the

oxide of the deoxidant

The refractories that are less stable than the

oxides of the deoxidant

Interaction between Liquid Steel and

Liquid Slag. Macroinclusion formation can

occur by emulsification of liquid slags or scums

on the surface of liquid steels. All of these types

of defects are practice related and can be solved

by practice changes. The issue in understanding

emulsification is to understand the source of the

energy that allows a buoyant droplet to become

submerged. Generally, this energy comes from

the interaction of a flowing steel stream and a

liquid slag. There are four major sources of this

energy:

Open stream pouring onto or through a

liquid slag (common during lip pouring)

Filling a ladle or mold at too high a fill rate in

the presence of slags or scums

Vortexing during steel pouring from a ladle

Steering in the ladle with gas at too high a

stir rate

Vortexing during drainage in a water model of

a ladle was studied by Sankaranarayanan and

Guthrie (Ref 20, 21). They showed that the

initial rotational velocity at the surface of the

vessel is extremely important in determining

the height at which the vortex will form, and that

increased rotational velocities caused increased

vortex initiation depth. Entrainment due to fluid

flow at the interface has been examined by

Noguchi et al. (Ref 22), who attempted to

decrease the entrainment of slag in low-carbon

titanium-aluminum-killed steels. They noted

that entrainment decreased as the casting speed

was decreased. In a study conducted by Naka-

mura et al. (Ref 23), it was found that defects that

contained mold slag increased in ultra-low-

carbon grades as the casting rate was increased.

They also reported using as low an argon flow

rate as possible in their submerged entry nozzles

to avoid entrainment. Manabu et al. (Ref 24)

have also documented the existence of a critical

gas flow rate for entrainment in both a silicon

oil-water and a slag-steel system. These authors

mention that the slag depth, slag properties, and

gas bubble diameter play a role. The oil depth

was found to be directly proportional to the flow

rate needed to cause entrainment. The gas bub-

ble size was found to be inve rsely proportional

to the flow rate needed to cause entrainment.

Manabu et al. (Ref 24), investigated the effect

of oil kinematic viscosities on emulsification

and found that although the kinematic viscosity

was varied by a factor of 10, very little change

was seen in the fluid velocity needed to cause

entrainment. Harman and Cramb (Ref 25),

documented the effect of interfacial tension and

slag viscosity on emulsification phenomena.

Erosion-Corrosion during Steel Pour-

ing. This kind of defe ct is usually associated

with the higher corrosivity of some steel grades,

because high manganese and grades that are

barely killed and have high soluble oxygen

contents attack the binder or the mold sand itself,

leading to large entrapped sand components.

Reoxidation of steel leads to FeO-based inclu-

sions that are very reactive and wet the materia ls

of the mold, leading to erosion of the mold in

areas of high fluid turbulence. Of course, sand

that is not pressed, sintered, or bonded in any

way can easily be entrapped in turbulent fluid

flow. Mold binders can also decompose at tem-

perature and release mold components that can

be entrapped. Expansion due to the high thermal

gradients associated with casting can also cause

sand to loosen.

Inclusion Agglomeration due to Clogging

during Steel Pouring. The formation of clogs

when steels containing solid inclusions are cast

can result in quite large macroinclusion defects

if the clogs are released during teaming. All

solid inclusions tend to agglomerate due to sur-

face tension effects. Clogging of pouring noz-

zles can be the source of large macroinclusion

defects when steels are dirty and pouring times

are long.

The Formation of Microinclusions

Microinclusions are formed due to reactions

between alloying additions and oxygen in mol-

ten steel. Their formation is generally hetero-

geneous or from highly supersaturated areas

during alloy addition. Due to the nature of the

formation of these inclusions (nucleation and

growth), they are generally small (less than

5 mm), unless they agglomerate due to turbu-

lence or grow under conditions of high oxygen

flux. In this study, microinclusions are defined as

those inclusi ons with diameters smaller than

20 mm. In addition, they are defined as having

Failures from the Casting Process / 167

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 167

diameters greater than 1 mm. Table 5 show

typical microinclusions that are found in cast

steels.

Since microinclusions form due to a reaction,

they are driven by thermodynamics; therefore,

changing composition or temperature can lead to

their precipitation. This means they can form in

the ladle, during transport to the mold, or in the

mold during solidification.

Case Studies of Defects Caused

by Inclusions

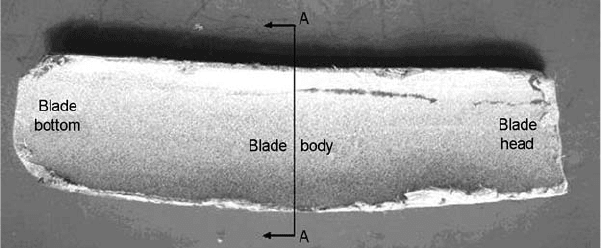

Failure of a Steam Turbine Rotor Blade.

Possible causes were investigated for failure of

a rotor blade of a 35 MW steam turbine. One of

the rotor blades was fractured after a certain

operation time (Fig. 23). The fracture occurred

at two different regions: at the bottom and at the

top extremity, near the metallic lashing strap.

Both regions have the highest stress concentra-

tion due to the blade geometry and loading

conditions. The blade fracture occurred during

the maximum turbine operation. The rotor was

working, with new blades mounted in between

harvests. The blades were manufactured with

steel ingots with the chemical composition pre-

sented in Table 6. The specifications for the

mechanical properties of the material at room

temperature are shown in Table 7.

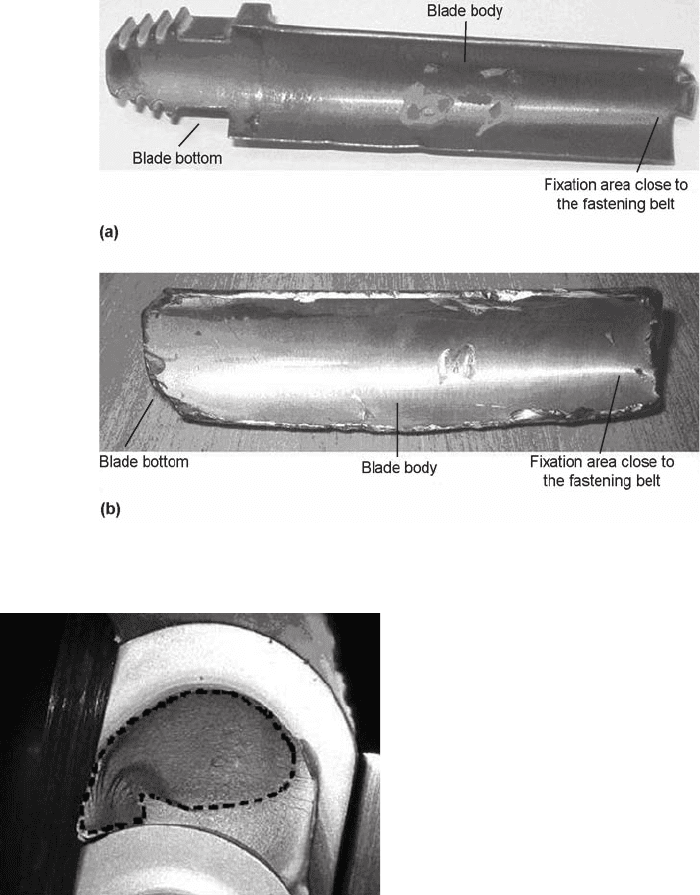

Figure 24 shows the fractured blade compared

to an intact one, with the fracture regions

indicated. Figure 25 shows a micrograph of the

fractured surface, near the blade bottom. Several

turning gear imprints can be observed, showing

the presence of multiple sites of crack nucleation

Table 5 Typical microinclusions found in cast steels

Steel type Microinclusion type Comments

Aluminum killed Alumina Formed in liquid steel after deoxidation

Manganese-silicon killed Manganese silicate or manganese-alumino

silicate

Formed in liquid steel after deoxidation

Calcium treated, aluminum killed Calcium aluminate Formed by reaction with alumina, liquid inclusion

Aluminum killed, with residual

magnesium

Magnesium aluminate Formed by reaction with alumina, solid inclusion

Titanium treated, aluminum killed Alumina, titania, titanium nitride Titania forms during reoxidation. Titanium nitride forms

during cooling, usually in the mold itself.

All steels Manganese sulfide Forms interdendritically during solidification. Often

nucleates on oxides already present in steels

Table 7 Mechanical properties specifications of FV520(B) steel

Yielding limit, MPa Strain limit, MPa Elongation, % Reduction in area, % Impact energy, J Hardness, HV

680–800 900–1050 20 min 55 min 40 min 270–320

Table 6 Nominal chemical composition of FV520(B) steel

Composition, wt%

CSiMnCrNiCuMoNbSP

0.07 max 0.7 max 1.0 max 13.2–14.7 5.0–6.0 1.2–2.0 1.2–2.0 0.2–0.5 0.06 max 0.03 max

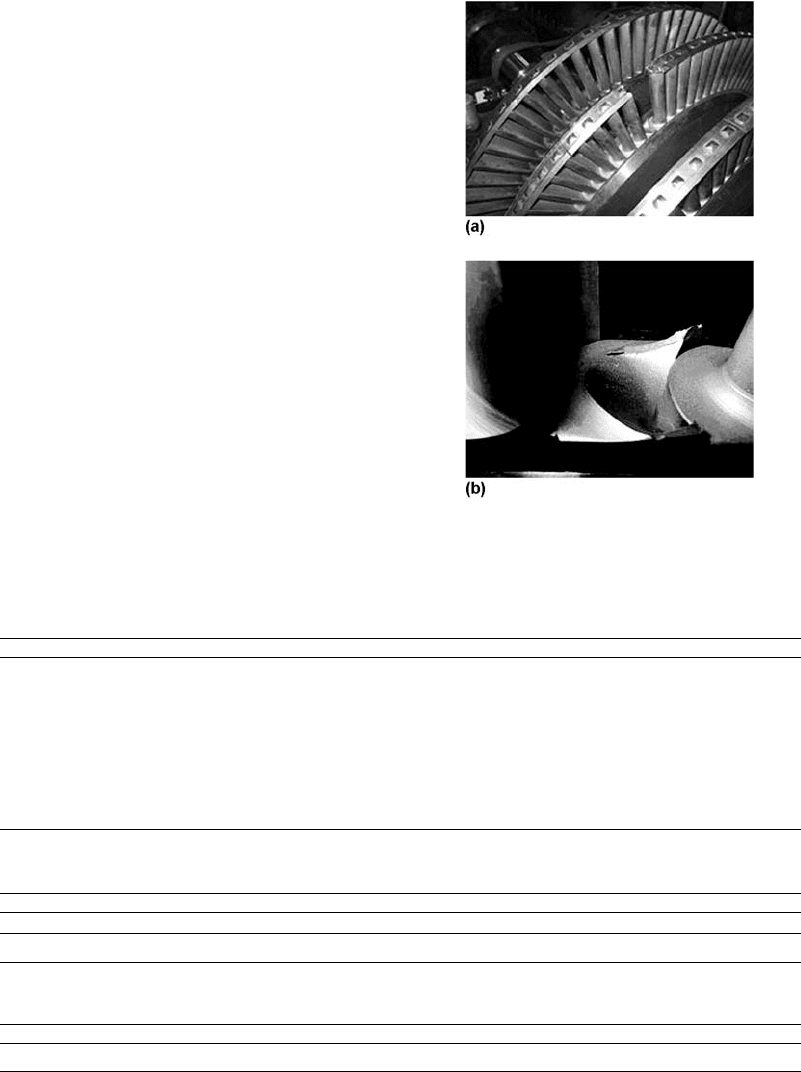

Fig. 23

(a) Turbine stage that had the fractured blade.

(b) Detail of the fractured bottom component of

the blade

168 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 168

by fatigue. A darkened region is observed on the

fracture surface, indicated by the dotted line,

suggesting that this area was more exposed to

steam and high temperatures during the turbine

operation time, and it occupies a significant

component of the fracture surface.

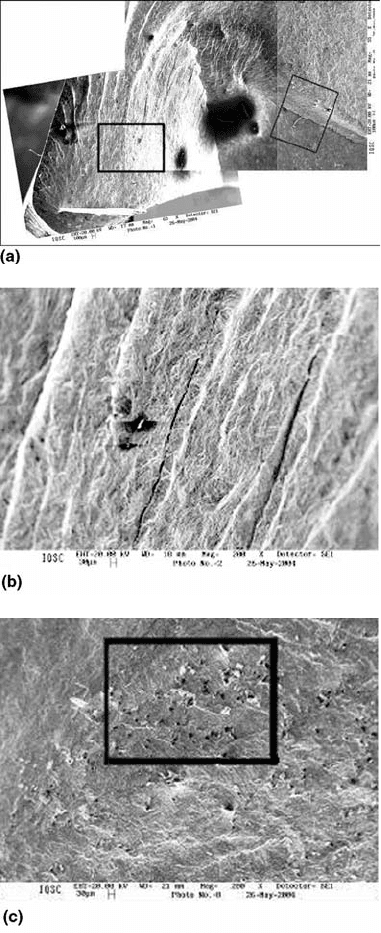

Penetrating liquid analysis indicated the pre-

sence of secondary longitudinal cracks in the

fractured material, normal to the main crack, at

the bottom of the blad e. The analysis made in the

blade body indicated the presence of a large,

longitudinal crack, probably consisting of an

extension of the cracks observed at the bottom of

the blade, as shown in Fig. 26. Optical micro-

scopy analysis of a cross section of the blade

body revealed a different microstructure from

the martensitic steel matrix located parallel to

the longitudinal crack in the blade body.

Because of this different microstructure,

electron-dispersive x-ray (EDX) analyses were

carried out in the regions around the longitudinal

crack in the structural sample. They showed a

chemical composition different from the nom-

inal, as much for the central region as for the

blade head region. The fracture surface of the

longitudinal crack revealed a microstructure rich

in silicon, oxygen, manganese, and calcium,

suggesting that the material contains a large

number of impurities, probably slag from the

casting process and certainly introduced during

the manufacturing process of the component.

The occurrence of these impurities impedes

surface welding during the process of forging,

creating a surf ace with a smashed aspect.

However, the first region where the nuclea-

tion probably occurred was the one near the

Fig. 24 (a) Intact blade. (b) Fractured blade

Fig. 25

Micrograph of the blade fracture surface showing

several turning gear imprints and the oxidized area

(dotted line)

Failures from the Casting Process / 169

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 169

longitudinal cracks detected by the penetrating

liquid. Indeed, the fractograph ic analysis of this

region shows a fracture morphology different

from the vicini ty, with several inclusion com-

ponents protruding into the fracture surface

(Fig. 27). The EDX microanalyses of these

components show a chemical composition with

a high level of carbon, which suggests that these

components are of iron carbide. Moreover,

several longitudinal cracks similar to the one

found in the blade body were observed.

Nonfusible longitudinal cracks exist along

the affected area in the blade. The large variety

of defects and the excessive mechanical vibra-

tion of the blade are probably the main causes of

crack nucleation by fatigue in the material near

the blade bottom. They culminated in the cata-

strophic fracture of the component.

The recommendation includes a more effi-

cient quality control of the manufacturing pro-

cess of the blade material and avoiding the

occurrence of casting defect formation, slag

inclusions, and other impurities.

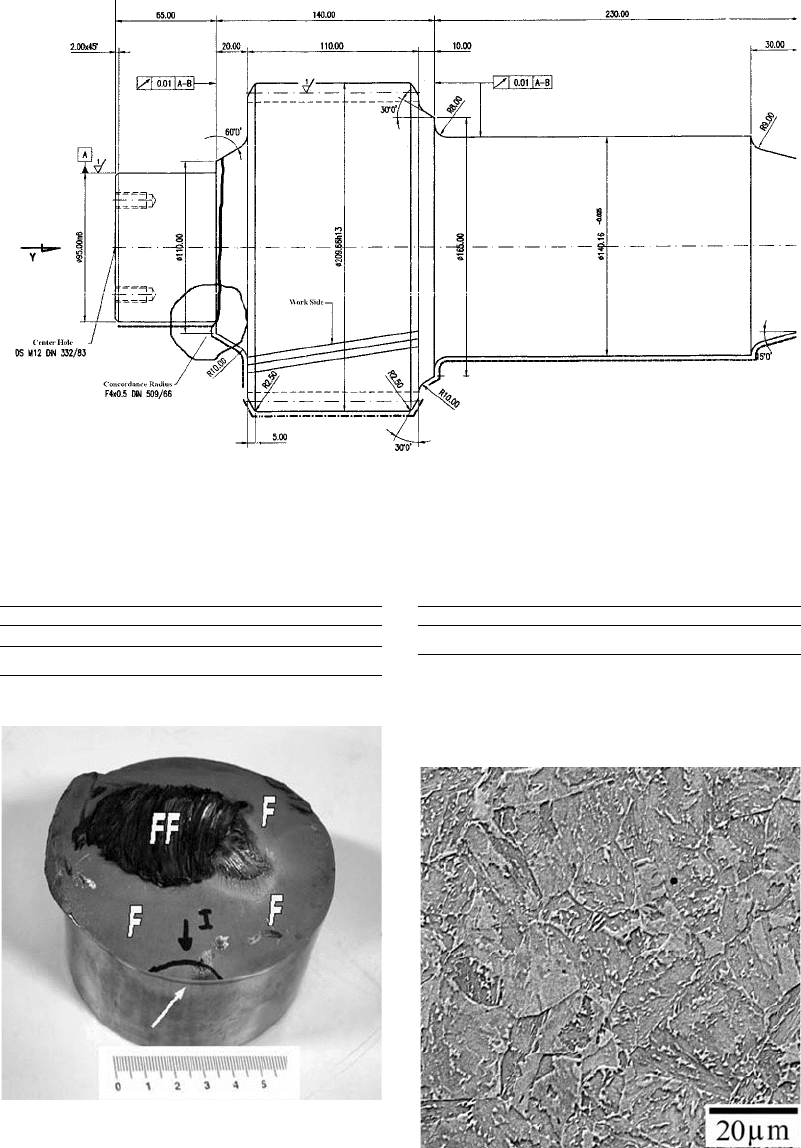

Failure in the Axle of a Reduced Section in

a Rotating Component. Possible causes were

investigated for failure in the area of an inter-

mediate reduction. The rotating component

fractured completely after intermittent loading.

Figure 28 shows an outline of the component

and the axle region where the cracks developed.

The chemical composition (in weight percent) of

the fractured axle material is provided in

Table 8. The results show that the axle material

is a DIN-specified 17CrNiMo6 steel. The spe-

cifications of the material mechanical properties

at room temperature are given in Table 9.

The visual inspection of the fracture surface

(Fig. 29) indicated an extremely flat aspect, such

as the ones typically displayed in fatigue cracks.

The flat fracture surface occupied approximately

80% of the cross section (Fig. 29), exactly in the

axis of the radius change for the concordance

section. Due to the small relative section area of

the fracture axis, approximately 20% of its cross

section, it was deduced that the stress for the in-

service component was relatively low.

Ten measurements of Rockwell C hardness

were carried out, according to ASTM E18, on

the surface of the axle near the fracture region. A

mean hardness of 33.9 HRC was obtained. This

value is well below the expected one of 43 HRC.

Figure 30 shows the microstructure of steel in

the reduced section on a longitudinal cut plane in

the vicinity of fatigue crack nucleation. The

material presents a large amount of globular or

granular bainite, in agreement with the relatively

low value of hardness of the fractured axle

surface.

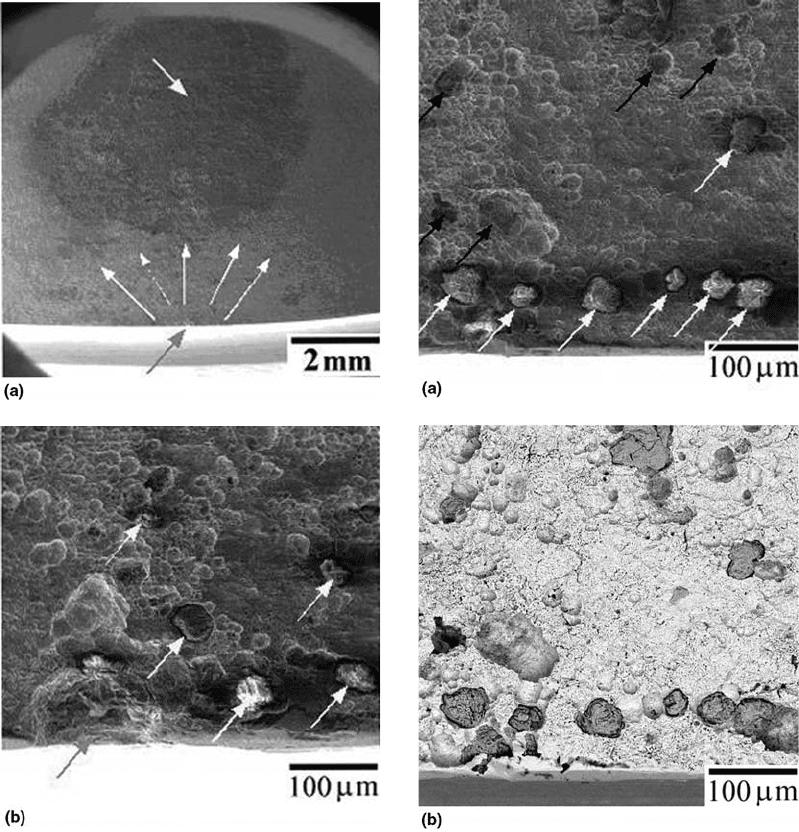

Figure 31(a) shows a general topview of the

fracture surface in the region where there was

fatigue crack nucleation, indicated by the arrow

at bottom. The five clustered arrows point in the

direction of fatigue crack propagation advance.

The arrow at the top shows a dark region, orig-

inated by contamination of the fracture surface

with oil or grease. Figure 31(b) shows in detail

the fatigue crack nucleating site that probably

started at an inclusion located exactly on the

circumference surface of the reduced section in a

region in the internal concordance radium. The

presence of some inclusions in the proximity

of the fracture site is pointed out by white arrows

in Fig. 31(b). Indeed, fractographic analysis

has shown the possibility of the existence of a

concentration of inclusions in the nucleation

region of the fatigue crack. Figure 32(a) con-

firms the high level of inclusions in the region,

indicated by white arrows, with signs of moving

Fig. 26

Longitudinal crack in the blade body revealed by penetrating liquid. The A-A section indicates the approximate position of

the cut made for structural observation.

170 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 170

by second-phase components indicated by black

arrows, similar to Fig. 31(b). Figure 32(b), the

same image shown in Fig. 32(a) but with back-

scattered electrons instead of secondary ones,

reveals the great amount of inclusions (darker)

in the metallic matrix (lighter). The chemical

analysis of the inclusions shows a massive

presence of aluminum, sulfur, and calcium

elements.

It is worth noting that these inclusions act,

on a microscopic scale, as metallurgical stress

concentrators. The presence of these second-

phase components especially near the external

axle surface where the maximum tensile stresses

are developed during a torsional load (and even

flexion) applied to the in-service component,

drastically reduces the lifetime in fatigue of the

rotating component. This happens through the

promotion of both mechanisms of nucleation

and fatigue crack propagation in their early

stages of growth.

It was concluded that crack initiation occurred

in the reducer axle by fatigue. A single crack

probably was nucleated on a nonmetallic inclu-

sion placed near the finish ed axle surface,

exactly in the internal component of the con-

cordance radius machined in the section change.

The combination of the effects of stress con-

centration generated by both discontinuities,

metallurgical (inclusion) and geometric (curva-

ture radius), created sufficient critical conditions

for fatigue crack nucleation that grew due to

the action of repetitive efforts of torsion (and

flexion) imposed in service to the rotating

component.

Failure of a 52100 Steel Axle. The raw

material (52100 steel) used in the manufacture

of an axle catastrophically fractured during

annealing heat treatment at 350

C. Figure 33

shows the fracture surface along with the cir-

cular cross section of the component (one of the

samples received for analysis). In the figure, the

arrow at left shows the main fracture plan e of

the axis (i.e., along a longitudinal plane), and

the arrow at right points to the starting point

of brittle fracture in its cross section. In Fig. 34,

this starting site is shown in detail (arrow at

bottom).

Figure 35 shows the microstructure of the

52100 steel, in the central region of the part in a

longitudinal plane, after etching with nital. The

massive presence of pearlite and the existence of

free cementite in both forms—globulized

(inside the pearlitic colonies) and veins (circling

the colonies)—is observed.

Figure 36 shows the vermiform dis-

continuities, with an appearance similar to

manganese sulfide inclusions, that are invariably

present in mechanical construction steels. The

presence of a grayish second phase, intermediate

to the metallic matrix (lighter) and the voids

Fig. 27

(a) General view of the probable initial region of

crack nucleation by fatigue crack. (b) Magnification

of the region in the box at the left in (a). (c) Magnification of the

region in the box at the right in (a)

Failures from the Casting Process / 171

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 171

Fig. 28

Component drawing of the intermediate I axle. Highlighted are the section change region where the fracture developed and

the crack propagation path for the total fracture of the axle.

Fig. 29

Complete cross-sectional fracture surface of the

intermediate I axle. The white arrow shows the

nucleating site of the fatigue crack. The surface generated by

the fatigue crack propagation is identified by “F,” while the final

fracture of the remaining section is indicated by “FF.”

Fig. 30

Microstructure of the axle according to a long-

itudinal cut plane. Etched with 2% nital

Table 8 Chemical composition of the axle

material

Composition, wt%

CMnSiP SNiCrMo

0.17 0.63 0.23 0.10 0.011 1.45 1.59 0.30

Table 9 Mechanical properties at room

temperature

s

E

, MPa s

R

, MPa A

F

,% Q

F

,%

742 1080 20 57

172 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 172

(darker), is observed inside these dis-

continuities. This material component fills the

larger discontinuities, while the smaller dis-

continuities are almost totally filled by the sec-

ond phase.

Figure 37 shows that the most subtle dis-

continuities have a rather slim, cracklike aspect

and consequently present a great capacity

to concentrate high tensile stress es. In these

terms, it is possible to assume that these second

phases are potential crack nuclei, and that they

also generate a preferential path for crack

propagation. It is worth emphasizing that the

majority of these discontinuities were found

aligned in the direction of the thermomechanical

work to which the axle was submitted during its

manufacture (i.e., longitudinal direction). The

inclusions are disp osed on parallel planes to the

main fracture of the component during heat

treatment. This suggests the possibility that

these inclusions played a fundamental role in the

catastrophic failure of the 52100 steel axle.

Fig. 31

Fatigue crack site. (a) General view. (b) Detail. The

inclusion that originated the site was removed from

the fracture surface. SEM image with secondary electrons

Fig. 32

Concentration of inclusions near the fatigue crack

site. (a) SEM image with secondary electrons.

(b) Backscattered electrons

Failures from the Casting Process / 173

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_151-176.pdf/Chap_05/ 18/8/2008 3:11PM Plate # 0 pg 173