Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

consumption, and there is no evidence that if such

food is primarily contaminated, illness ensues. How-

ever uncooked soft fruits such as strawberries and

raspberries have been implicated in a number of out-

breaks when contamination is assumed to have oc-

curred at the growing site. Salad items are commonly

implicated in outbreaks, although in many of these

incidents, contamination is believed to have origin-

ated from infected food handlers at the time of prep-

aration.

Secondary Contamination: Food Handlers

0026 Viruses causing gastroenteritis and hepatitis A are

infectious in very low doses, and thus are spread

very readily from infected persons. It is now recog-

nized that outbreaks arising from infected food hand-

lers are common occurrences. The foods that pose the

greatest risk to the consumer are cold items, such as

sandwiches and salads, that require much handling

during preparation. Without meticulous attention to

personal hygiene and thorough and frequent hand

washing, fecally contaminated fingers can contamin-

ate foods and work surfaces. Viral gastroenteritis can

be very sudden in onset and commence with projectile

vomiting. The virus can be disseminated over a wide

area in aerosol droplets so that, in food preparation

areas, exposed foods, working surfaces, and door

handles are likely to be contaminated.

Virus Survival

0027 Gastroenteritis viruses and hepatitis viruses are

robust viruses and survive extremely well in the en-

vironment. It is the NLVs and HAV that are the most

resistant to inactivation. There is little precise infor-

mation on the stability of NLVs, since they cannot be

cultured in the laboratory. Most information on sur-

vival and inactivation has come from epidemiological

observations in outbreaks and limited studies of infec-

tivity in volunteers. Some strains of HAV and rota-

virus can be cultured, and there have been a small

number of experimental studies on their stability.

Gastroenteritis and hepatitis viruses have been

detected in food, water, and other environmental

samples by PCR assays, but such assays only detect

the viral genome and do not necessarily correlate with

infectivity.

0028 Viruses that infect via the gastrointestinal tract are

acid-stable. Both NLVs and HAV retain infectivity

after exposure to acidity levels below pH 3. Hence,

they are often able to survive the food-processing and

preservation conditions used to inhibit bacterial and

fungal spoilage of foods, such as pickling in vinegar

and fermentation processes to produce foods such as

yogurt. Alcohol and high sugar concentrations are

unlikely to have any adverse effect on survival. Re-

frigeration and freezing are routinely used to preserve

viruses and have no effect on viability. Frozen foods

that are not subsequently cooked, such as soft fruits,

have been implicated in a number of incidents of both

viral gastroenteritis and hepatitis A.

0029The viruses are destroyed by normal cooking pro-

cesses. For foods that only undergo partial cooking in

special heat processes, such as the treatment of shell-

fish and other pasteurization procedures, care must

be taken to ensure that inactivation of virus is

achieved. Both NLVs and HAV retain infectivity

after heating to 60

C for 30 min.

0030Gastroenteritis viruses and hepatitis viruses appear

to survive in the environment for long periods. They

survive on inanimate surfaces, on hands and in dried

fecal suspensions. Lingering outbreaks have occurred

in hospitals, residential homes and on cruise ships,

probably as a result of environmental contamination.

NLVs have been detected by PCR in swabs from

hospital lockers and hotel carpets supposedly cleaned

after incidents of vomiting.

0031There is conflicting evidence on the efficacy of

disinfectants. Chlorine-based disinfectants are usu-

ally considered the most effective against enteric vir-

uses and the most suitable in food preparation areas.

However, NLVs and HAV are resistant to a level of

0.5–1 mg per liter of free residual chlorine, which is

consistent with that present in drinking water. NLVs

are inactivated by 10 mg per liter of chlorine. In the

USA, a level of 5 mg per liter of chlorine with a

contact time of 1 min is recommended for inactiva-

tion of HAV. Infectivity of HAV is reduced by sodium

hypochlorite, 2% glutaraldehyde, and quarternary

ammonium compounds, but there are no compara-

tive data for NLVs.

Virus Detection

In Food

0032It is not feasible to examine food samples routinely

for the presence of viruses. Although it has been

possible to culture HAV since 1980, primary isolation

is a lengthy and unreliable procedure, and there have

been very few isolations of virus from food or water

samples. Virus was isolated from a drinking water

supply responsible for a large outbreak in the USA,

but this involved culture of highly concentrated water

samples for up to 21 weeks. There have been several

studies involving recovery of virus from artificially

contaminated foods, particularly shellfish, but these

have used highly adapted laboratory strains of virus.

Viruses stick avidly to shellfish meat, and complex

extraction techniques are required. Even with the best

6008 VIRUSES

of these methods, virus recovery rates are poor. NLVs

cannot be cultured in the laboratory. Culture of rota-

viruses and astroviruses is complex and unreliable,

and the problems of avidity similarly apply. Rapid

solid-phase immunoassays are available for the detec-

tion of hepatitis and gastroenteritis viruses. These are

not sufficiently sensitive, however, to detect the very

small numbers of virus particles likely to be present in

contaminated foods. Similarly, electron microscopy is

insufficiently sensitive for the detection of virus in

food samples.

0033 There is considerable interest in the application of

PCR assays to the detection of viruses in food and

water samples. PCR is an extremely sensitive tech-

nique. However, extraction of viral RNA from

samples and removal of PCR inhibitors is a fairly

complex and time-consuming procedure. Hence,

such assays cannot be used for routinely screening

food samples. Furthermore, unlike culture, a positive

PCR result only indicates the presence of viral nucleic

acid and does not necessarily confirm the presence of

viable infectious virus. These tests do have an import-

ant role in the epidemiological investigation of out-

breaks and assessing the efficacy of treatment

procedures.

In Patients

0034 HAV is excreted in feces, but it is not usually appro-

priate to examine fecal specimens for virus as the

main excretion period precedes illness. The usual

diagnostic test is detection of anti-HAV specific im-

munoglobulin M (IgM) antibody in serum, for which

there are a number of commercially available solid-

phase immunoassays. The presence of IgM antibody

is indicative of recent infection. If the fecal specimens

are collected at the appropriate time, it is quite feas-

ible to detect viral antigen by various techniques, the

most rapid and straightforward being the solid-phase

immunoassays and PCR tests.

0035 All the gastroenteritis viruses were discovered by

electron microscopy, and this has continued to play

an important role in diagnosis. Viruses from different

groups look different, and it is this characteristic

morphology that is the basis for their identification.

However, electron microscopy is a time-consuming

technique that demands considerable skill and ex-

perience on the part of the operator, and it is not

a technique that lends itself to examining large

numbers of specimens. PCR assays are being used

increasingly for the detection of NLVs, but their use

is mainly confined to specialist virology laboratories.

Although of far greater sensitivity than electron mi-

croscopy, current primers will not detect all strains of

NLVs. Recombinant capsid antigens have been made

from a small number of NLV strains and have been

used to develop ELISA tests. So far, only a very few

NLV types can be detected, and the tests are not yet

widely available. Commercial ELISA and latex agglu-

tination test kits are readily available for the detection

of rotaviruses. Astroviruses are usually detected by

electron microscopy. Some laboratories use in-house

PCR assays or culture combined with immunofluor-

escence.

Prevention and Control

0036Elimination of viral contamination at source is an

ideal that is unlikely to be attained in the near future.

In practice, it would be necessary to prevent the dis-

charge of sewage into rivers and coastal waters,

which not only pollutes water supplies that may be

used for irrigation but also results in the contamin-

ation of shellfish. Sewage sludge provides beneficial

nutrients and is applied to agricultural land as fertil-

izer. In developed countries, increasingly stringent

regulations for the use of untreated or partially treated

sewage are being introduced. Since the end of 1999,

application of all untreated sewage sludge on agricul-

tural land has been prohibited in the UK. Where

treated sewage is applied to land for growing salad

and vegetable crops, permitted time intervals, be-

tween applying the sewage and harvesting the crops,

are specified. Hepatitis A is endemic in underdevel-

oped areas of the world and viral gastroenteritis

more prevalent. Viruses commonly occur in polluted

coastal waters in these areas, and contamination of

shellfish is likely. Standards for the use of sewage in

agriculture are also less satisfactory. Imports of fruits,

salads, vegetables and shellfish could potentially pose

a risk to consumers.

0037It is usual practice to treat shellfish in some way to

remove microbial contamination before they are sold

to the public. In the European Union, conditions for

bivalve molluscs are laid down in the European

Council Directive on Shellfish Hygiene (91/492/

ECC), and there are similar regulations in the USA.

Shellfish, such as oysters and mussels, may be

cleansed, either by relaying in cleaner coastal or estu-

arine waters or by transfer to land-based depuration

facilities. Harmful microorganisms should be washed

out during the natural feeding process. These proced-

ures are remarkably successful in removing bacterial

contamination but do not completely eliminate vir-

uses. These may remain for several weeks in molluscs

held in depuration tanks. Even though molluscs

may appear entirely satisfactory in bacteriological

tests, incidents of viral illness may follow their

consumption.

0038Up to the middle of the 1980s, many outbreaks

of viral illness were recorded, related to the

VIRUSES 6009

consumption of inadequately cooked shellfish such as

cockles. Prolonged cooking results in a tough unpal-

atable product, and thus the aim of treatment must be

to apply the minimum heat necessary to render shell-

fish safe. Studies on the inactivation of hepatitis A

virus in shellfish led to recommendations that the

internal temperature of shellfish meat should be

raised to 90

C and maintained for 1.5 min. These

recommendations were adopted by the UK shellfish

industry and subsequently accepted as a valid method

of treatment by the European Commission. Later

studies, using feline calicivirus as a model, indicated

that these conditions were also adequate for inactiva-

tion of the NLVs. Epidemiological evidence strongly

supports the view that this treatment is effective for

the inactivation of gastroenteritis viruses. Since early

1988, there have been no further reports in England

and Wales of any viral illness, either hepatitis A or

gastroenteritis, from shellfish heat-treated according

to the recommendations.

0039 Foods may be contaminated during preparation

and serving by infected food handlers. Both the gas-

troenteritis viruses and hepatitis A virus are extremely

infectious in low doses and thus are spread easily

from infected persons. Persons with symptoms should

be excluded from handling food. However, food

handlers with very minimal symptoms have been im-

plicated in the transmission of NLVs. There is a little

circumstantial evidence that asymptomatic excretion

of virus occurs, but in the absence of more definitive

data, it is generally recommended that people should

be allowed to resume work 48 h after symptoms have

ceased. That recommendation was based on the rapid

decline in virus shedding observed by electron micro-

scopy and in practice appears to work satisfactorily.

However, NLVs often can be detected by PCR for a

longer period than by electron microscopy and, in

some instances, for up to a week after the onset of

symptoms. It is not clear if persons shedding virus

detectable by PCR are infectious after symptoms

have ceased. Recommendations on how long to ex-

clude people from work need to be kept under review.

0040 Excretion of hepatitis A virus precedes symptoms,

and hence, early exclusion of infectious food handlers

is not usually possible. An effective vaccine is avail-

able. Currently, in the UK, hepatitis A vaccine is used

selectively for persons at high risk, such as travelers.

It is not generally used for food handlers except in

outbreak situations. If exposure is known to have

occurred, the use of normal human immunoglobulin

might be considered in persons at risk of developing

illness.

0041 In the kitchen, prevention of transmission of vir-

uses through foods largely depends on rigorous appli-

cation of normal good hygiene practices, including

frequent hand washing and thorough washing of

fruit and vegetables. Shellfish must be regarded as a

potential source of infection, and uncooked shellfish

should be kept separate from other food items that

are not to be cooked. If vomiting occurs, virus may be

spread over a wide area. Uncovered food should be

discarded. Even food that is to be cooked is a poten-

tial source of cross-contamination. Work surfaces,

door handles, and toilet areas should be cleaned thor-

oughly. Chlorine-based disinfectants are considered

the most effective. Handling of food should be kept

to a minimum. Wearing gloves may prevent fecally

contaminated fingers coming into contact with food

but will not prevent transfer of organisms from con-

taminated work surfaces.

See also: Contamination of Food; Food Poisoning:

Statistics; Shellfish: Contamination and Spoilage of

Molluscs and Crustaceans; Zoonoses

Further Reading

Advisory Committee on the Microbiological Safety of Food

(1998) Report on foodborne viral infections. London:

The Stationery Office.

Appleton H (2000) Control of foodborne infections. British

Medical Bulletin 56: 172–183.

Cliver DO (1997) Foodborne viruses. In: Doyle MP, Beu-

chat LR and Montville TJ (eds) Food Microbiology:

Fundamentals and Frontiers, pp. 437–446. Washington,

DC: ASM Press.

Desslberger U (2000) Viruses associated with acute diar-

rhoeal disease. In: Zuckerman AJ, Banatvala JE and

Pattison JR (eds) Principles and Practice in Clinical Vir-

ology, 4th edn., pp. 235–252. Chichester, UK: John

Wiley.

Evans HS, Madden P, Douglas C et al. (1998) General

outbreaks of infectious intestinal disease in England

and Wales: 1995 and 1996. Communicable Disease

and Public Health 1: 165–171.

Food Standards Agency (2000) A report of the study of

infectious intestinal disease in England. London: The

Stationery Office.

Harrison TJ, Dusheiko GM and Zuckerman AJ (2000)

Hepatitis viruses. In: Zuckerman AJ, Banatvala JE and

Pattison JR (eds) Principles and Practice in Clinical Vir-

ology, 4th edn., pp. 187–233. Chichester, UK: John

Wiley.

Hui YH, Sattar SA, Murrell KD, Nip W-K and Stanfield PS

(eds) (2000) Foodborne Disease Handbook, Volume 2:

Viruses, Parasites, Pathogens, and HACCP, 2nd edn.

Chapters 2–9. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Lees D (2000) Viruses and bivalve shellfish. International

Journal of Food Microbiology 56: 81–116.

Millard J, Appleton H and Parry JV (1987) Studies on

heat inactivation of hepatitis A virus with special refer-

ence to shellfish. Epidemiology and Infection 98:

397–414.

6010 VIRUSES

Public Health Laboratory Service Viral Gastroenteritis Sub-

Committee (1993) Outbreaks of gastroenteritis associ-

ated with SRSVs. PHLS Microbiology Digest 10: 2–8.

Seymour IJ and Appleton H (2001) A review: Foodborne

viruses and fresh produce. Journal of Applied Microbiol-

ogy 91: 759–773.

Slomka MJ and Appleton H (1998) Feline calicivirus as a

model system for heat inactivation studies of small

round structured viruses in shellfish. Epidemiology and

Infection 121: 401–407.

Wheeler JG, Sethi D, Cowden JM et al. (1999) Study of

infectious intestinal disease in England: rates in the com-

munity, presenting to general practice, and reported to

national surveillance. British Medical Journal 318:

1046–1050.

Visible Spectroscopy See Spectroscopy: Overview; Infrared and Raman; Near-infrared;

Fluorescence; Atomic Emission and Absorption; Nuclear Magnetic Resonance; Visible Spectroscopy and

Colorimetry

Vitamin A See Retinol: Properties and Determination; Physiology

Vitamin B

1

See Thiamin: Properties and Determination; Physiology

Vitamin B

12

See Cobalamins: Properties and Determination; Physiology

Vitamin B

2

See Riboflavin: Properties and Determination; Physiology

VIRUSES 6011

VITAMIN B

6

Contents

Properties and Determination

Physiology

Properties and Determination

J A Driskell, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Vitamin B

6

: Properties and Analysis

0001 Vitamin B

6

is a B-complex vitamin. Vitamin B

6

is the

generic descriptor for all 3-hydroxy-2-methylpyridine

derivatives possessing the biological activity of pyrid-

oxine.

0002 Gyu

¨

rgy, in 1934, identified vitamin B

6

as a curative

factor for a characteristic dermatatis in the laboratory

rat. The first naturally occurring form of the vitamin

was isolated in 1938; its structure was confirmed

by chemical synthesis as 3-hydroxy-4,5-bis(hydroxy-

methyl)-2-methylpyridine in 1939. ‘Pyridoxine’ was

the trivial name of this compound, and ‘pyridoxine’

and ‘vitamin B

6

’ were synonyms. Other compounds

having vitamin B

6

activity were detected and isolated.

In the 1960 IUPAC Definitive Rules for the Nomen-

clature of Vitamins, ‘pyridoxine’ was recommended

as the generic descriptor of the B

6

vitamers and ‘pyr-

idoxol’ as the trivial name of the alcohol form of the

vitamin. In the 1966 IUPAC-IUB Tentative Rules, the

suggestion was made that ‘pyridoxol’ should be

designated as ‘pyridoxine.’ In 1968, the IUPAC-IUB

Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature decided

to publish a special document regarding vitamin B

6

nomenclature, which clearly stated that ‘pyridoxine

should not be used as a generic name synonymous

with vitamin B

6

’; this document, published in 1973,

also designated the composition of the six forms of

the vitamin and oxidized metabolites, 4-pyridoxic

acid and 4-pyridoxolactone. However, confusion

still exists in the literature regarding usage of the

term ‘pyridoxine.’

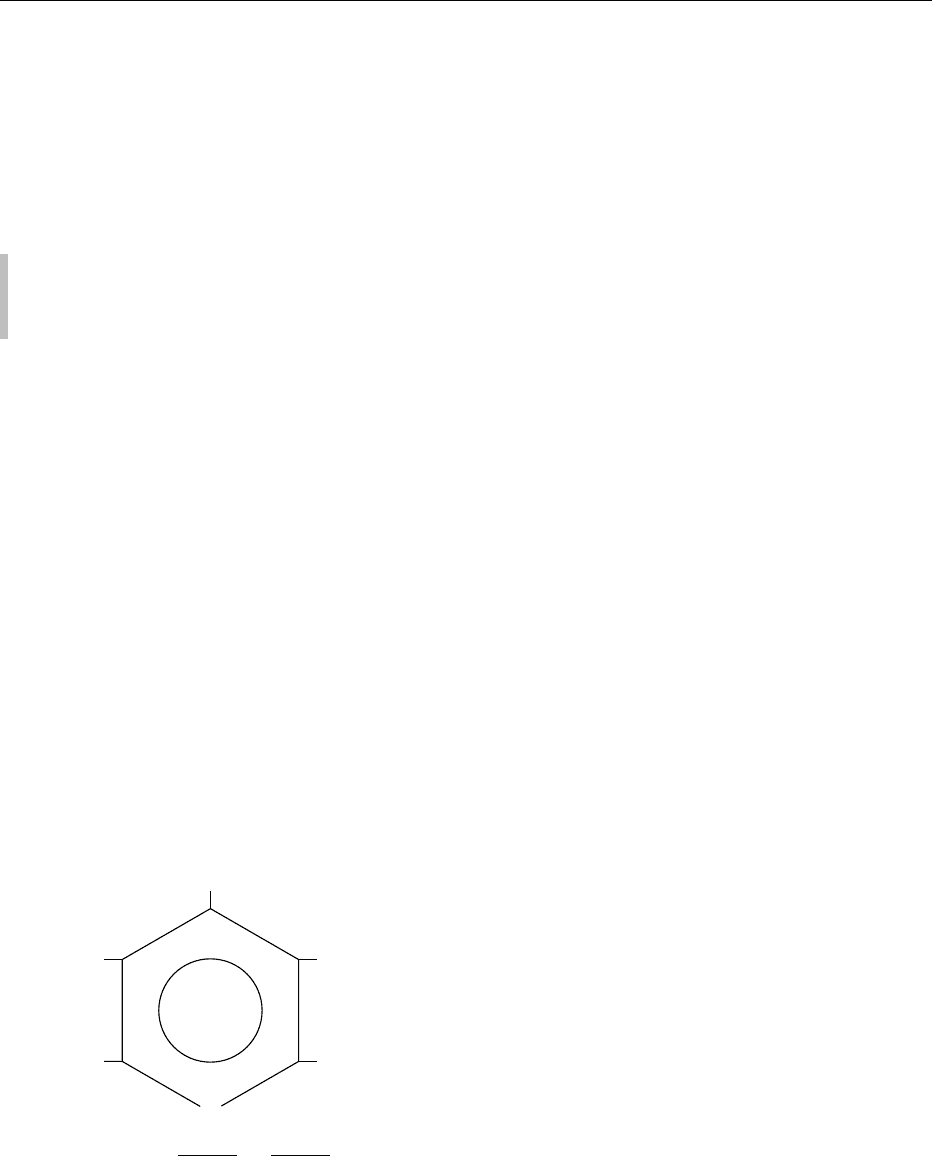

0003The chemical structures of the vitamin B

6

com-

pounds and the accepted ring numbering system are

shown in Figure 1. The vitamin B

6

congeners are

pyridoxine (PN), pyridoxal (PL), and pyridoxamine

(PM) – alcohol, aldehyde, or amine groups are at

the #4 position of the pyridine ring. Each of these

three forms also has a corresponding 5

0

-phosphate

(P), i.e., pyridoxine 5

0

-phosphate (PNP), pyridoxal

5

0

-phosphate (PLP), and pyridoxamine 5

0

-phosphate

(PMP). The various forms of the vitamin are bio-

chemically interconvertible, as shown in Figure 2.

They can also be chemically interconverted. The

major excretory form of the vitamin is 4-pyridoxic

acid (4-PA), which is eliminated in the urine.

Physical and Chemical Properties

0004In general, the various vitamin B

6

compounds are

white crystals that are very soluble in water, slightly

soluble in alcohol, and often insoluble in ether. They

melt, usually with decomposition. Aqueous solutions

of the various vitamin B

6

compounds are relatively

sensitive to light and often are destroyed by heating.

The light sensitivity of the vitamers is affected by pH.

The nonphosphorylated vitamers are relatively stable

to heat at an acidic pH but not at an alkaline pH.

According to Ang, stability values of PNHCl,

PLHCl, and PM2HCl at pH 4.5 to white light

for 8 h are 97, 97, and 81%, respectively, which

decreases with increasing pH. For example PNHCl

stability is 88% pH 7; at PLHCl, 81% at pH 6;

and PM2HCl, 74% at pH 8. Overall, PN is the

most stable, followed by PL and then PM. Greater

H

3

CH

62

N

R

1

4

1

HO

35

CH

2

OR

2

PN

PL

PM

4-PA

CH

2

OH

R

1

CHO

CH

2

NH

2

COOH

H

R

2

H

H

H

PNP PO

3

−

*When -CH

2

O

.

PO

3

, then is PNP, PLP, or PMP.

=

*

fig0001 Figure 1 Stuctural formulae of vitamin B

6

compounds.

6012 VITAMIN B

6

/Properties and Determination

decomposition of the vitamin B

6

compounds is ob-

served with ultraviolet and near-ultraviolet radiation.

Researchers working with this nutrient generally per-

form their analyses in darkened laboratories (red or

yellow lights may be used); in addition, media con-

taining the vitamin are kept at temperatures of 5

C

or less.

0005 The physical properties of the vitamin B

6

com-

pounds are summarized in Table 1. The ultraviolet

absorption spectra of these compounds are dependent

upon the pH because of changes to the electronic

structure. The pyridine ring of the vitamin B

6

com-

pounds is zwitterionic at neutral pH with ionized

phenolate and pyridinium groups. The physical prop-

erties of the B

6

compounds are useful with regard to

detection and quantitation of the vitamin.

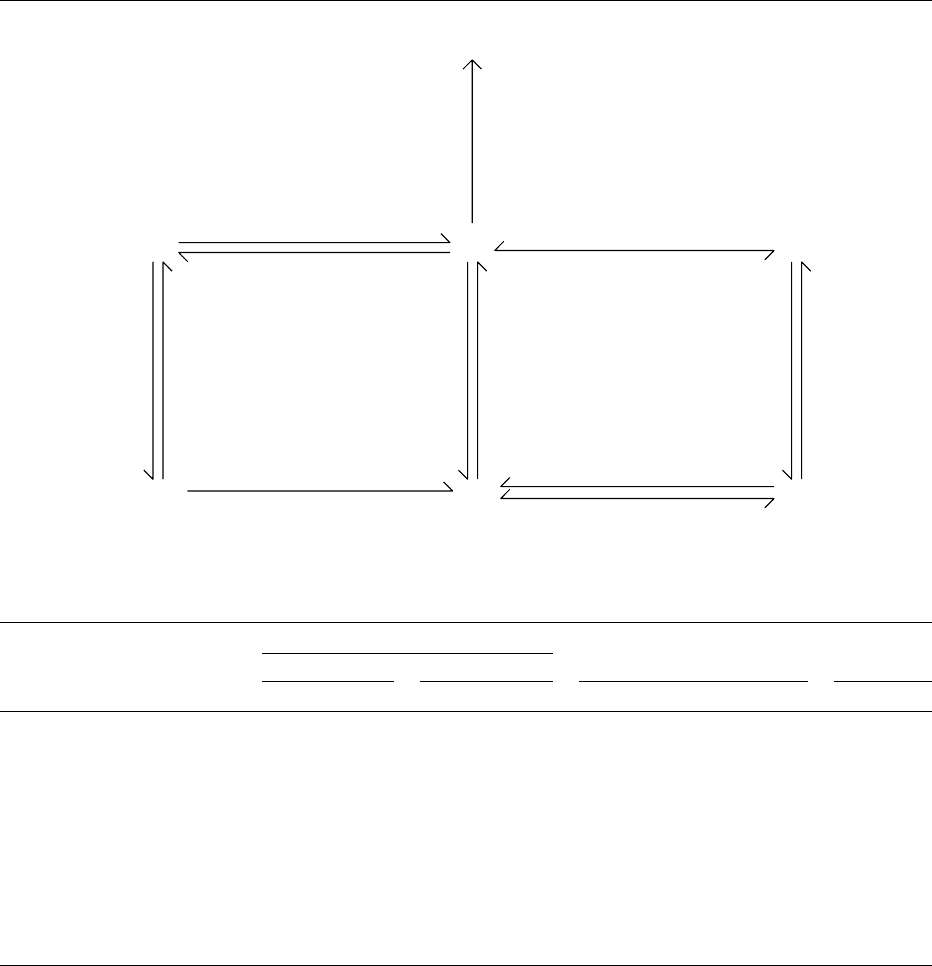

0006As mentioned previously, the various forms of vita-

min B

6

are interconvertible. The various B

6

vitamers

4-PA

Pyridoxine dehydrogenase (NADP)

[EC 1.1.1.65]

Pyridoxaminephosphate oxidase (FMN)

[EC 1.4.3.5]

Pyridoxaminephosphate oxidase (FMN)

[EC 1.4.3.5]

an Aminotransferase (PLP)

an Aminotransferase (PLP)

PM

Phosphatase

(perhaps Zn)

[EC 3.1.3.2]

Phosphatase

(perhaps Zn)

[EC 3.1.3.2]

Phosphatase

(perhaps Zn)

[EC 3.1.3.2]

Pyridoxal

kinase

(ATP, Zn)

Pyridoxal

kinase

(ATP, Zn)

PL

PLP PMP

PN

PNP

Aldehyde oxidase (FAD)

[EC 1.2.3.1]

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD)

[EC 1.2.1.3]

or

[EC 2.7.1.35] [EC 2.7.1.35]

Pyridoxal

kinase

(ATP, Zn)

[EC 2.7.1.35]

fig0002 Figure 2 Interconversions of vitamin B

6

compounds.

tbl0001 Table 1 Physical properties of vitamin B

6

compounds

a

Ultraviolet absorptionspectra

0.1 N HCl pH 7.0 Fluorescence maxima, pH 7 pK

Congener Molecular weight (g) l

max

(nm) e

max

l

max

(nm) e

max

Activation (nm) Emission (nm) pK

1

pK

2

PN 169.1 291 8700 254 3760 325 400 5.0 8.9

PL 167.2 288 9100 390 8800 320 385 4.2 8.7

PM 168.1 293 8500 253 4600 325 405 3.4 8.1

325 7700

PNP 249.2 290 8700 253 3700 322 394 – –

325 7400

PLP 247.2 293 7200 388 5500 330 375 <2.5 4.1

334 1300

PMP 248.2 293 9000 253 4700 330 400 <2.5 3.5

325 8300

4-PA 183.2 – – – – 325

b

425

b

––

355

c

445

c

a

Data from Storvick CA, Benson EM, Edwards MA and Woodring MJ (1964) Chemical and microbiological determination of vitamin B

6

. Methods of

Biochemical Analysis XII: 183–276; Harris SA (1968) Pyridoxine. Encyclopedia of Chemical Toxicology 16: 806–824; Brin M (1978) Vitamin B

6

: chemistry,

absorption, metabolism, catabolism, and toxicity. In: Human Vitamin B

6

Requirements, pp. 1–20. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; Ubbink JB

(1992) Vitamin B

6

. In: DeLeenheer AP, Lambert WE, and Nelis HJ (eds) Modern Chromatographic Analysis of the Vitamins, 2nd edn., Chapter 10. New York:

Marcel Dekker.

b

pH 3.4, 0.01 N acetic acid.

c

pH 10.5, 0.1 N NH

4

OH, lactone of 4-PA.

VITAMIN B

6

/Properties and Determination 6013

can change from one form to another during food

processing and food preparation, and in the body.

Occurrence and Forms in Foods

0007 Information regarding the vitamin B

6

content of

foods has been obtained primarily via microbiological

assay, although some values are available which were

obtained by high-performance liquid chromatog-

raphy (HPLC) methodologies, which can differenti-

ate between the vitamers. In the microbiological

assay techniques, acid (generally hydrochloric acid)

is used in extracting the vitamin from the food; the

acid hydrolyzes phosphates. Hence, vitamer values

obtained using microbiological methods represent

the sum of the phosphorylated and nonphosphoryl-

ated forms of the vitamin. Frequently, total vitamin

B

6

concentration values are obtained rather than

values for the individual vitamers.

0008 Food composition values are available for the three

forms of the vitamin (PL þPLP, PN þPNP, and

PM þPMP) in various foods. These can be found

in the USDA’s publication Pantothenic Acid. Vitamin

B

6

and Vitamin B

12

in Foods. In some reports, the

individual phosphate and free-base forms are also

available.

0009 A high proportion of the B

6

vitamers in plant-

derived foods is glycosylated PN, primarily as 5

0

-

b-d-glucoside. PL, primarily as the phosphorylated

form, is generally the predominant B

6

vitamer in

animal-derived foods. Different foods vary somewhat

as to which form of the vitamin is predominant.

0010 Vitamin B

6

found in unprocessed foods is mainly

bound to proteins. Table 2 gives the vitamin B

6

content of selected foods. This information can be

obtained by accessing the USDA food composition

website or from a variety of printed formats such as

McCance and Widdowson. Meats, whole-grain prod-

ucts, and nuts are good sources of vitamin B

6

.

Cultured cheeses and other fermented products are

also good sources of the vitamin. Fruits and vege-

tables are generally rather poor sources. PN, PM,

and PL have been reported to have equal potencies

in the rat. In humans, dietary PM and PL are about

10% less effective than PN, as indicated by effects on

plasma PLP and urinary 4-PA levels according to a

previous report. In the human body, the nonpho-

sphorylated forms of vitamin B

6

can be converted to

their respective phosphorylated forms and vice versa

by pyridoxal kinase and pyridoxamine (pyridoxine)

phosphate oxidase (see Figure 2). Recently, these

kinase and oxidase enzymes have been identified as

potential targets for pharmacologic agents.

0011 Glycosylated vitamin B

6

is found in all plant-type

foods. The glycosylated vitamin B

6

contents of

selected foods can be found in various publications.

Gregory indicated that a mixed diet contains about

15% of glycosylated vitamin B

6

, which is about 50%

as available as the other B

6

vitamers. This is often

excluded from food composition data. Bioavailability

is of importance in that it reflects the quantity of a

consumed nutrient that becomes available to the cells

of the body.

Effects of Food Processing and

Preparation Methods upon Vitamin B

6

Content of Foods

0012Vitamin B

6

is one of the more labile nutrients. The

vitamin is stable to dry heat; its stability in moist heat

is largely dependent upon the pH of the media, being

relatively stable to heat in an acidic media but not in

alkaline media. The vitamin is unstable to light, both

visible and ultraviolet. The vitamin undergoes rapid

destruction or loss during cooking procedures.

0013Food processing and subsequent storage may also

have an effect upon the vitamin B

6

content of various

foods. The retention of the vitamin is quite high fol-

lowing the processing of dry foods. Thirty to 50% of

the vitamin B

6

present in whole milk and infant for-

mulas is retained following liquid processing includ-

ing sterilization treatments, whereas the spray drying

of these products results in minor loss. Storage of

canned dairy products shows no degradation over

2–3 years. The same is true with regard to commercial

canning and irradiation of boned chicken, although

the retention is better for the irradiated than the

canned product. Heat processing by retorting results

in vitamin B

6

losses in several products. The stability

of the vitamin in dehydrated foods is affected by

moisture content, water activity, and storage condi-

tions. Food-processing techniques generally result in

losses of 0–50% of the vitamin.

0014Vitamin B

6

aldehydes can bind to food proteins as

e-pyridoxyllysine complexes during thermal process-

ing and low-moisture storage. Gregory has shown

that the protein-bound e-pyridoxyllysine has

antivitamin B

6

effects in rats. This pyridoxyllysine

complex may also affect vitamin B

6

availability to

humans, particularly with regard to the vitamin in

unfortified infant formulas.

0015Much of the vitamin loss is due to cooking and

holding practices of consumers and food service per-

sonnel. The retention of the vitamin in oven-braised

beef rounds prepared in food service establishments

has been reported to range from 45 to 62%; values

for green beans are slightly higher, whereas those for

baking potatoes prepared in the skins are around

80%. The vitamin B

6

content of meats and vege-

tables has been shown to decrease following various

6014 VITAMIN B

6

/Properties and Determination

household cooking procedures, even when foods

were cooked according to standard recipes or

manufacturer’s instructions. The retention of vitamin

B

6

in selected vegetables has been found to be highest

for those steamed in plastic bags, followed by those

boiled in plastic bags, those steamed, and lastly, for

those boiled. Boiling results in degradation and leach-

ing but the retention of the vitamin in vegetables

following microwave steaming or regular microwave

cooking techniques is around 90%. It has been found

that more vitamin B

6

is retained when beef and

pork strips are cooked by stir-frying (*67%) than

tbl0002 Table 2 Vitamin B

6

content of selected foods

Food Edible portion

(mgper100 g)

Food Edible portion

(mgper100 g)

Meats

Bacon 0.270 Ham, cured, roasted 0.310

Beef, ground, broiled, medium 0.270 Herring, Atlantic, cooked, dry heat 0.348

Beef, components, separable lean and fat,

trimmed, choice, cooked

0.320 Lamb, composite, separable lean, choice, cooked 0.160

Bologna, beef 0.180 Liver, chicken, simmered 0.580

Bologna, pork 0.270 Mackerel, Atlantic, cooked, dry heat 0.460

Chicken Oysters, Eastern, raw 0.050

Dark with skin, roasted 0.310 Pork, composite, separable lean, roasted 0.404

Light with skin, roasted 0.520 Pork sausage, fresh, cooked 0.330

Frankfurters, beef 0.110 Salmon, Sockeye, cooked, drained 0.219

Haddock, cooked, dry heat 0.346 Shrimp, breaded, fried 0.098

Halibut, cooked, dry heat 0.397 Tuna, canned in water, drained 0.350

Dairy products

Butter 0.003 Eggs 0.139

Buttermilk 0.034 Milk

Cheese Whole 0.042

Cottage, creamed 0.067 2% 0.043

Cheddar 0.074 Skim 0.040

Swiss 0.083 Yogurt 0.032

Cereal and grain products

Bread Rice

White 0.064 White, short-grain, cooked 0.059

Whole wheat 0.097 Brown, medium-grain, cooked 0.149

Pumpernickel 0.126 Wheat, germ, toasted, plain 0.978

Vegetables

Asparagus, solids, drained 0.122 Collards, boiled, drained 0.128

Beans Corn, sweet, boiled, drained 0.060

Lima, boiled, drained 0.193 Lettuce, looseleaf, raw 0.055

Snap, green, boiled, drained 0.056 Mushrooms, raw 0.102

Beets, boiled, drained 0.067 Onions, raw 0.116

Broccoli, boiled, drained 0.143 Peas, green, boiled, drained 0.216

Brussels sprouts, boiled, drained 0.178 Potatoes, boiled, without skin 0.269

Cabbage, boiled, drained 0.113 Potatoes, flesh 0.301

Carrots, raw 0.147 Potatoes, French-fried, restaurant-prepared 0.243

Cauliflower, boiled, drained 0.173 Spinach, boiled, drained 0.242

Celery, raw 0.087 Tomatoes, red, ripe, raw 0.080

Fruits

Apples, raw 0.048 Orange, raw 0.060

Avocados, raw 0.280 Orange juice, fresh 0.040

Blueberries, raw 0.036 Peaches, raw 0.018

Cherries, sour, red raw 0.044 Pears, raw 0.018

Grapefruit, raw 0.042 Raisins, seedless 0.249

Grapes, American type, raw 0.110 Strawberries, raw 0.059

Nuts and seeds

Almonds, dry roasted, unblanched 0.126 Peanuts, dry roasted 0.296

Cashew nuts, dry roasted 0.256 Pecans, dried 0.187

Coconut meat, dried, unsweetened 0.300 Walnuts, dried 0.537

Mixed nuts, dry roasted, with peanuts 0.296

Alcoholic beverages

Beer 0.050 Wine, table 0.024

Data from US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (1999) USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 13.

VITAMIN B

6

/Properties and Determination 6015

by microwaving (*60%) or by broiling (*58%).

More vitamin B

6

is retained when pork roasts are

cooked to an internal temperature of 71

C (62%)

than 82

C (54%) and this retention is greatest when

pork is cooked in a bag than roasted or braised.

Vitamin B

6

retention has been found to be similar

(68%) in bison patties cooked by grilling and by

broiling. In summary, loss of some vitamin B

6

is inev-

itable during all household/food service preparation,

to a greater or lesser extent.

Fortification of Foods with Vitamin B

6

0016 PNHCl is listed on the generally recognized as safe

(GRAS) list of the US Food and Drug Administration

and is used in the fortification of foods, particularly

various cereal and dairy products. This form of the

vitamin is also used in dietary supplements and

pharmaceutical products. PNHCl is resistant to

destruction by heat as well as by other factors but

should be protected from light and moisture. Pharma-

ceutical products containing this vitamin have been

reported to have less than 10% loss in vitamin activ-

ity after storage at room temperature for 1 year.

Methods of Analysis

0017 There are two basic stages in procedural methods

dealing with quantitation of vitamin B

6

components

– preparative or extraction techniques and determina-

tive methods. Several excellent reviews have been

published on methods of vitamin B

6

analysis in-

cluding chromatographic techniques. Many methods

have been utilized in quantitating the vitamin B

6

components in foods. These include animal and

microbiological growth, enzymatic, fluorometric, im-

munologic, gas chromatographic (GC), and HPLC

assays.

Extraction Techniques

0018 The major problem encountered in quantitating

vitamin B

6

in plant or animal products is extraction.

Vitamin B

6

compounds must be extracted from food

products before being analyzed by microbiological,

chromatographic, and other methods. Vitamin B

6

frequently occurs in biological materials in associ-

ation with proteins. The most common bond for PLP

is the Schiff base linkage with the e-amino group of

lysine. The Schiff base linkage is easily hydrolyzed by

deproteinizating agents.

0019 Great care must be taken during sample handling

and extraction and with relation to the stability of the

different vitamers as well as their interconversions.

The samples must be homogenous and representative

of the bulk product.

0020Conventional methods for extracting vitamin B

6

compounds from foods entail the use of high tem-

perature and acidic media to denature the protein

and disrupt the sample matrix. The phosphate esters

of PNP, PLP, and PMP are hydrolyzed by autoclaving

in acidic media. The microorganisms used in micro-

biological assays lack response to the phosphates.

Efficient extraction of vitamin B

6

compounds is

obtained using a sample size containing 2–4 mgof

the vitamin and hydrolyzing in 180 ml of 0.055 N

H

2

SO

4

for 1 h at 128

C (20 psi, 138 kPa); 0.44 N

sulfuric acid under the same conditions is essential for

all plant products. Thermal extractions of pH 1.7–1.8

have been found to be optimally effective for most

samples; this pH range corresponds closely to the

0.055 N sulfuric acid, which was recommended

earlier. Hydrochloric acid is also used in thermal ex-

tractions of the vitamin. Complete hydrolysis of PLP

is achieved after autoclaving the sample in 0.055 N

hydrochloric acid at 121

C (15 psi, 103 kPa) for 1 h;

however, 5 h are required for extraction of the

vitamin from dried yeast and liver powder. Complete

hydrolysis of PMP requires 3 h at 125

C in 0.055 N

hydrochloric acid, whereas PLP is hydrolyzed com-

pletely in 30 min. The B

6

vitamers in rice bran are best

hydrolyzed using 2 N hydrochloric acid. The AOAC

method of thermal hydrolysis for B

6

vitamers is as

follows: use 1–2 g of dry product; add 200 ml of 0.44

N hydrochloric acid for plant products followed

by autoclaving at 121

C for 2 h and for animal

products, add 200 ml of 0.055 N hydrochloric

acid, and autoclave at 121

C for 5 h; after the

solution has cooled to room temperature, adjust

the pH to 4.5 with 6 N or saturated potassium hy-

droxide; then dilute to 250 ml with water and filter,

using Whatman No. 40 paper. Complete release of

both protein-bound and phosphorylated forms of the

vitamin is essential for quantitative assay using

microorganisms.

0021Perchloric acid, trichloroacetic acid, and sulfo-

salicylic acid may be used as deproteinating agents.

These acids are particularly useful when one desires

to quantitate phosphorylated, nonphosphorylated,

and glycosylated forms of the vitamin individually,

as use of these agents does not result in dephosphoryl-

ation or deconjugation. If so desired, trichloroacetic

acid may be removed from the extract by extraction

with diethyl ether or freon amine. Perchloric acid can

also be removed from the extract by precipitation

with potassium hydroxide; and sulfosalicylic acid

can be removed via ion-exchange chromatographic

techniques. Metaphosphoric acid has been used in

extraction of the vitamin from brain tissue. This

acid does not need removal from the extract prior to

many of the HPLC techniques for vitamin B

6

assay.

6016 VITAMIN B

6

/Properties and Determination

0022 Extraction procedures must solubilize the vitamers

for subsequent quantitation. The effectiveness of the

extraction procedures may be determined by evalu-

ation of recoveries of B

6

vitamers added during

sample homogenization or, even better, by incorpor-

ation of radiolabeled forms of the vitamin into the

sample, called intrinsic labeling.

Animal Growth Assays

0023 Bioassays are based on the growth response of

animals, usually rats or chicks, to purified diets con-

taining graded levels of a standard vitamin to the

sample being tested. An advantage of the method is

that the vitamin in the sample does not have to be

extracted. Animal assays are not used very frequently

because of their lack of specificity as well as their

expense and time requirement. The intestinal micro-

flora of these animals may affect the data; efforts to

prevent coprophagy or the use of antibiotics are not

completely effective.

Microbiological Assays

0024 The vitamin B

6

composition of plant and animal

products is generally determined using microbio-

logical assays. These assays are tedious, and none

are without problems. The most widely used micro-

biological assay is a growth assay using the yeast

Saccharomyces uvarum (ATCC 9080; formerly S.

carlsbergenesis). Growth is measured via turbidity

using a spectrophotometer. Unfortunately, the re-

sponse of many cultures of the yeast to PM is fre-

quently 60–80% of that to PN and PL. It is

advisable to evaluate the magnitude of the response

differences under the conditions of each assay. PL,

PN, and PM can be separated by subjecting the acid

extractant to cation-exchange chromatography on

Dowex AG 50W-X8 resin using KOAc solutions of

three different pHs; each form of the vitamin is then

analyzed, utilizing its respective calibration curve.

Care must be taken to assure proper separation of

the vitamers and avoid cross-contamination of the

three fractions.

0025 The yeast Kloeckera brevis (ATCC 9774; formerly

K. apiculata) may be used in quantitating total vita-

min B

6

. Some researchers indicate that K. brevis

has an equal growth response to PL, PN, and PM,

whereas others indicate that it has an even lower

relative response to PM than S. uvarum. The K. brevis

assay has been adapted to radiometric quantitation.

0026 The total, as well as the three nonphosphorylated

vitamers, may also be determined by a differential

microbiological technique. S. uvarum responds to PL,

PN, and PM, whereas Streptococcus faecalis R (ATCC

8043) responds to PL and PM, and Lactobacillus

casei (ATCC 7469) responds to only PL. Tetrahy-

mena pyriformis, a protozoan, has also been used as

an assay organism.

0027Saccharomyces uvarum is the microorganism used

in the AOAC method. The concentrations of the three

nonphosphorylated B

6

vitamers are quantitated in

this method.

0028Assays for glycosylated vitamin B

6

compounds in

foods have been developed utilizing S. uvarum and

differential hydrolytic procedures. This method does

have a tendency to underestimate the quantity of

the glycosylated vitamin in raw plant foods having

p-glycosidase activity.

0029Values given in food composition tables have

been derived primarily using S. uvarum as the test

organism. These tables generally list total vitamin B

6

concentrations but may list PL, PN, and PM con-

centrations. The Center for Nutrient Analysis of

the US Food and Drug Administration uses S.

uvarum for quantitating vitamin B

6

in foods. Data

obtained microbiologically using S. uvarum do not

always agree with those obtained by animal growth

assays.

Enzymatic Assays

0030Several enzymatic methods are available that quanti-

tate PLP, the main circulating form of vitamin B

6

.

These methods are frequently utilized as parameters

for the assessment of vitamin B

6

status of animals,

including humans but are not utilized in the analysis

of food samples. The enzymatic methods that have

been more commonly used include the following:

the cleavage of tryptophan using apotryptophanase

(EC 4.1.99.1), the measurement of aspartate amino-

transferase (EC 2.6.1.1; formerly referred to as

glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase), and alanine

aminotransferase (EC 2.6.1.2; formerly referred to

as glutamic-pyruvic transaminase) activities, and the

radiomonitored decarboxylation of [

14

C]tyrosine

using the apoenzyme of tyrosine decarboxylase (EC

4.1.1.25). Currently, the most acceptable enzymatic

method of quantitating PLP is the tyrosine apode-

carboxylase technique.

Fluorometric Assays

0031Direct fluorometric analysis of vitamin B

6

in extracts

of plant and animal products is generally unsatisfac-

tory. This is due to the presence of many potentially

interfering compounds that fluoresce, as well as the

varying spectral characteristics of the B

6

vitamers. As

a result, the total vitamin B

6

content of selected foods

is higher when measured by fluorometry following

open-column chromatography than published values

based on microbiological assay.

VITAMIN B

6

/Properties and Determination 6017