Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

0042 The power of a test is also shown in the calculated

variance of d

0

: the more powerful the test, the smaller

the variance of d

0

. This variance is very useful when

comparing several d

0

values (for instance, when com-

paring a standard to several reformulations) in order

to determine whether they are significantly different

from each other.

0043 Replicated testing Considering the sample sizes

required for the duo–trio and triangle tests, it would

be more suitable to use the 2- or 3-AFC protocols. If it

is impossible to use the directional difference tests,

the power of the triangle and duo–trio tests can be

somewhat increased by replicating the number of

tests per subject. However, combining data from dif-

ferent subjects brings the issue of overdispersion. Ref-

erences in the Further Reading section at the end of

this chapter should be consulted in order to insure

accurate data analysis.

0044 Experimental variables Under certain conditions, d

0

values obtained from discrimination tests may not

correspond exactly. This may be due to the effect of

experimental variables such as memory and sequence/

adaptation effects which are not considered in the

models. Since a larger d

0

value requires a smaller

sample size to be detected, it may be beneficial to

use protocols providing larger d

0

values. Experimen-

tally, it has been found that memory requirements can

significantly hinder subjects’ performance and thus

product discrimination. Under certain conditions,

tests with only two samples (2-AFC, same–different)

have been found more sensitive (higher d

0

value) than

those with more stimuli (3-AFC, triangle).

0045 This aspect of difference testing should also be

considered when selecting a protocol to conduct a

discrimination study.

Conclusion

0046 For an unaware scientist, the topic of discrimination

testing can be perceived as deceptively simple and

limited. However, we showed here that proper know-

ledge from psychology, physiology, and statistics is

necessary in order to insure proper data collection

and analysis. Furthermore, discrimination testing

can provide very valuable information by not limiting

the information to a mere yes/no answer regarding

the existence of a difference. This can be achieved by

calculating d

0

values and their variances from widely

available tables, and by determining the magnitude of

the difference between the samples.

0047 This chapter summarized the scope of this topic.

The reader is advised to refer to the review articles

cited at the end of this section in order to build a more

general knowledge about the topic of discrimination

testing.

0048We still need to mention that the concepts of

sensory magnitudes and d

0

values are not limited to

sensory difference tests and that they can easily be

extended to ratings on category scales and consumer

preference and hedonic data. This approach is ex-

tremely useful for sensory science since it allows the

connection of all kinds of sensory measurements in a

common structural framework.

See also: Carbohydrates: Sensory Properties; Sensory

Evaluation: Sensory Characteristics of Human Foods;

Food Acceptability and Sensory Evaluation; Practical

Considerations; Sensory Rating and Scoring Methods;

Descriptive Analysis; Appearance; Texture; Aroma; Taste

Further Reading

Bi J, Ennis DM and O’Mahony M (1997) How to estimate

and use the variance of d

0

from difference tests. Journal

of Sensory Studies 12: 87–104.

Brockhoff PB and Schlich P (1998) Handling replications in

discrimination tests. Food Quality and Preference

9: 303–312.

Ennis DM (1993) The power of sensory discrimination

methods. Journal of Sensory Studies 8: 353–370.

Ennis DM and Bi J (1998) The beta-binomial model:

accounting for inter-trial variation in replicated differ-

ence and preference tests. Journal of Sensory Studies 13:

389–412.

Green DM and Swets JA (1966) Signal Detection Theory

and Psychophysics. New York: Wiley.

Kaplan HL, Macmillan NA and Creelman CD (1978)

Tables of d

0

for variable-standard discrimination para-

digms. Behavior Research Methods and Instrumentation

10: 796–813.

Lawless HT and Heymann H (1998) Sensory Evaluation of

Food: Principles and Practices. New York: Chapman &

Hall.

Macmillan NA and Creelman CD (1991) Detection

Theory: A User’s Guide. New York: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Meilgaard M, Civille GV and Carr BT (1999) Sensory

Evaluation Techniques, 3rd edn. Boca Raton: CRC

Press.

O’Mahony M (1986) Sensory Evaluation of Food: Statis-

tical Methods and Procedures. New York: Marcel

Dekker.

O’Mahony M (1995) Who told you the triangle test was

simple? Food Quality and Preference 6: 227–238.

O’Mahony M, Masuoka S and Ishii R (1994) A theoret-

ical note on difference tests: models, paradoxes

and cognitive strategies. Journal of Sensory Studies 9:

247–272.

Stone H and Sidel JL (1993) Sensory Evaluation Practices,

2nd edn. San Diego: Academic Press.

SENSORY EVALUATION/Sensory Difference Testing 5147

Sensory Rating and Scoring

Methods

J A McEwan, MMR Food and Drink Research

Worldwide, Wallingford, UK

D H Lyon, Campden Food and Drink Research

Association, Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Purpose of Rating and Scoring Methods

0001 Rating and scoring methods provide the basis for

quantification of sensory information. Although

these two terms are sometimes used interchangeably

by sensory scientists, they have different meanings.

0002 Rating refers to the quantification of information

by the use of ordinal categories, while scoring is a

more defined form of rating as it uses a numerical

interval or a ratio scale, of which the properties are

known. A scale can be defined as a measurement

continuum divided into successive units according to

the properties associated with it.

0003 There are many different rating and scoring

methods used in sensory analysis, as illustrated both

here and in other articles. In each case, these scales are

physical measurement tools used to measure some

sensory phenomenon perceived by individuals. Thus,

implicit in using rating and scoring is that these scales

provide meaningful representations of some psycho-

logical process or processes.

0004 When considering rating and scoring methods, the

reader should be aware that the experimental design

considerations given to sensory analysis procedures

should be observed. In this article, example forms

are given with the illustrations of different scales

to aid the reader in designing appropriate question-

naires.

Type of Scale

0005 Four types of scale can be used to collect data: nom-

inal scales, ordinal scales, interval scales, and ratio

scales.

Nominal Scale

0006 A nominal scale is one where data collected are cat-

egorized by a name or a number. Each observation

collected using these scales must fall within one of the

categories. For example, ‘canned,’‘frozen,’‘dried,’

‘chilled,’ and ‘fresh’ are five categories used to de-

scribe methods of food preservation. These categories

have no logical ordering and, thus, the key point

about nominal scales is that the different categories

have no quantitative relationship.

Ordinal Scale

0007An ordinal scale is one which allows observations to

be ordered according to whether they have more or

less of a particular attribute. Successive numbers or

words are used to indicate more (or less) of the attri-

bute being measured. Ordinal scales do not allow the

amount of difference between observations to be

quantified. The nine-point hedonic scale (described

later) is ordinal, as are ranked data.

Interval Scale

0008An interval scale is one where the distance between

points on the scale is quantifiable. In many instances,

the distance or intervals between points on a scale will

represent an equal perceptual distance. For example,

if the perceptual distance between 1 and 2 on a seven-

point scale of sweetness was the same perceptual

distance as between 2 and 3, 3 and 4, and so on,

then this scale would have interval properties.

Ratio Scale

0009A ratio scale is one where the observations collected

can be expressed as a percentage or ratio of each

other. For example, a person eating 100 g of chocolate

a day eats twice as much as a person eating 50 g day

1

.

An example of a ratio scale in sensory analysis is

magnitude estimation, which will be discussed later.

The main difference between interval and ratio scales

is that the latter has a true zero, whereas the zero

point of an interval scale is arbitrary.

Data Collection Methods and Data

Analysis

Nominal Data

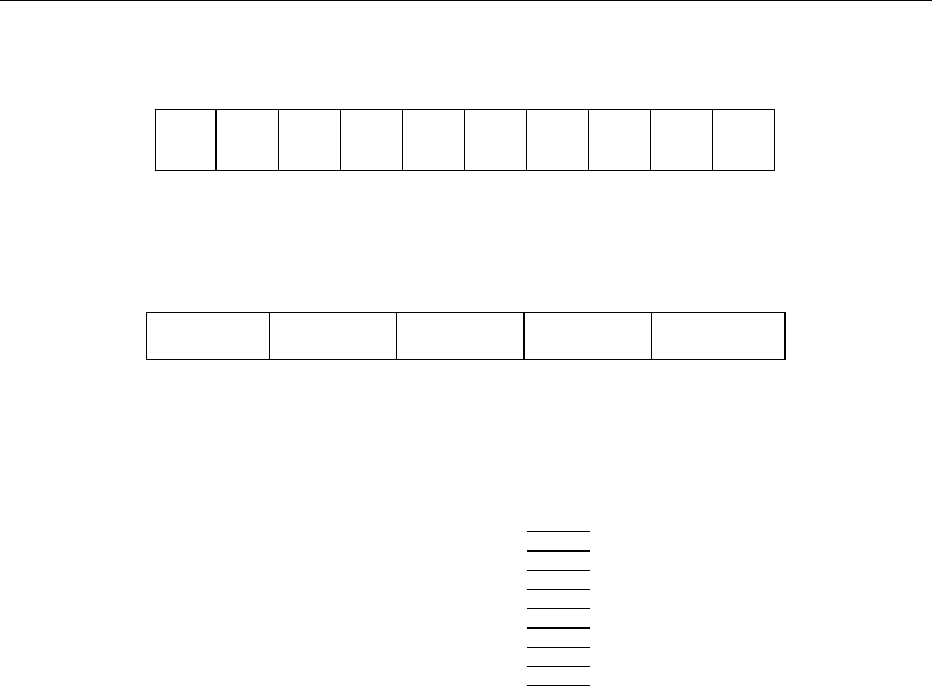

0010Nominal data can be collected in a number of ways

(Figure 1), but common to all nominal data is that

each observation can only fall into one category. A

logical first step in analysis and interpretation of the

data, therefore, is to produce a histogram indicating

Please taste the sample coded 457, and identify which of

the four basic tastes you perceive.

Sweet

Sour

Salt

Bitter

Unable to

Identify

fig0001Figure 1 Taste identification test using a nominal scale.

5148 SENSORY EVALUATION/Sensory Rating and Scoring Methods

the frequency of occurrence of each category. The

next step is to determine whether more observations

fall in one category than another, or if the distribution

of counts for one sample is the same as for another. In

either case, the usual method of analysis is by the w

2

(chi-squared) test.

0011 A more advanced method for treating nominal data

is the technique of multiple correspondence analysis.

This method produces a multidimensional spatial

representation of the relationship between samples

and attributes, which is often a useful summary of

the data.

Rating Methods

0012 Rating methods involve the quantification of per-

ceived sensations by the use of scales.

0013 Category scales Category scales are widely used in

sensory analysis, both for objective assessment and

affective (related to preference or liking) response.

Category scales for objective sensory measurement

are most often unipolar, as it is the amount of a

particular attribute which is being measured. An

example of a unipolar scale for firmness is given in

Figure 2. A category scale may also be constructed

such that each category has a verbal label attached to

it, as illustrated in Figure 3. Bipolar scales can be used

to measure attributes such as texture, e.g., substitute

the two anchors of Figure 2 with ‘soft’ and ‘firm,’

respectively. While these scales give the appearance

of having interval properties, care should be taken

in making this assumption without experimental

evidence. Generally speaking, category scales pro-

vide ratings and not scores; thus, category scales

provide ordinal data.

0014 A well-known scale for affective measurement is

the nine-point hedonic scale (Figure 4). Variations of

this rating scale exist, comprising fewer categories

and the absence of the middle category.

0015Continuous line scales Continuous line or visual

analog scales take the form of an unstructured line,

as illustrated in Figure 5. Such scales are usually

unipolar and measure the two extremes of an attri-

bute, the extremes of which are represented as anchor

points at the left and right of the scale. The length of

the line is often 100 mm, although this may be longer

or shorter according to need. However, research con-

ducted by both psychologists and market researchers

has indicated that 100 mm is satisfactory. A line that

is too short may decrease the discrimination achiev-

able by the assessors, while beyond a particular length

it is unlikely that an assessor will provide more

precise information.

0016Continuous line scales are often used with trained

sensory panels as they allow the assessor to be more

discriminating than with the category scale. Data

collected on rating scales are measured by an interval

ruler; however, strictly speaking the data should be

considered ordinal, as it is usually impossible to prove

Please taste the sample coded 658, and indicate how firm it is by placing a tick in

the appropriate box below.

Not firm

Very firm

0

123456789

fig0002 Figure 2 Evaluation of the texture attribute firm, using a numeric category scale.

Please taste the sample coded 943, and rate the sweetness intensity by placing a tick in

the appropriate box below.

Not

sweet

Slightly

sweet

Moderately

sweet

Very

sweet

Extremely

sweet

fig0003 Figure 3 Evaluation of the taste attribute sweet, using a verbal category scale.

Please taste the sample coded 183, and indicate how much you

like or dislike the flavor by placing a tick by the appropriate

descriptor.

Like extremely

Dislike extremely

Like very much

Dislike very much

Like moderately

Dislike moderately

Like slightly

Neither like nor dislike

Dislike slightly

fig0004Figure 4 Hedonic assessment of flavor using a nine-point

verbal category scale.

SENSORY EVALUATION/Sensory Rating and Scoring Methods 5149

the linear (interval) properties of every continuous

line scale used for sensory measurement.

0017 With a trained sensory panel, continuous line scales

are usually assumed to be linear with the understand-

ing that the extremes of the scale may be slightly

curved due to end effects. If continuous line scales

were truly interval, then the data would be scores

rather than ratings. It would be unwise, however, to

make this assumption with an untrained panel or a

consumer panel without justification.

0018 Data analysis Data that have interval properties

can be analyzed using parametric statistical methods,

providing certain assumptions are satisfied. These

methods assume that the data are normally distrib-

uted, which implies a symmetric distribution (i.e., the

mean, median, and mode are equal) and that the data

have interval or ratio properties. Parametric methods

of analysis are powerful methods for sensory interval

data as they enable more precise interpretation to be

made of the results. There is a wide range of statistical

methods available for interval data, depending on the

question being asked. The simplest form of analysis is

to calculate means and standard deviations, which

measure the location and spread of the data, res-

pectively.

0019 This can be taken one step further by calculation of

a standard error and confidence interval for the mean.

This allows the sensory analyst to make inferences

about the mean of a sample with respect to the attri-

bute being measured, or to test a hypothesis that the

mean is equal to a particular value. t-tests can be used

to test the hypothesis that two samples have different

mean values for a particular attribute, while analysis

of variance will test whether more than two samples

have different mean values.

0020 When several attributes are being evaluated, multi-

variate analysis procedures are often adopted. Tech-

niques that can be used include principal component

analysis (PCA), generalized Procrustes analysis,

factor analysis, discriminant analysis, canonical

variate analysis, and cluster analysis.

0021 Whilst data collected by rating methods are mostly

ordinal, it is a common practice to use the univariate

parametric statistical methods discussed. However,

these methods assume that the data are derived from

an underlying normal distribution, which assumes

that the data are continuous, i.e., they have interval

or ratio properties. Clearly, by definition, ordinal

data cannot be continuous. In fact, for each of the

above-mentioned parametric statistics there is a non-

parametric equivalent. These are medians (means),

interquartile ranges (standard deviations), Mann–

Whitney U-test and Wilcoxon paired test (t-tests),

and the Kruskal–Wallis and Friedman rank test

(analysis of variance).

0022Multivariate analysis on ordinal data can be

achieved through correspondence analysis (CA),

which reduces the dimensionality (number of meas-

ured attributes) to a smaller number of dimensions,

which effectively describes the correspondence be-

tween samples and attributes. However, there is little

evidence to suggest that CA is better than PCA for

sensory profile data collected on ordinal scales.

Magnitude estimation

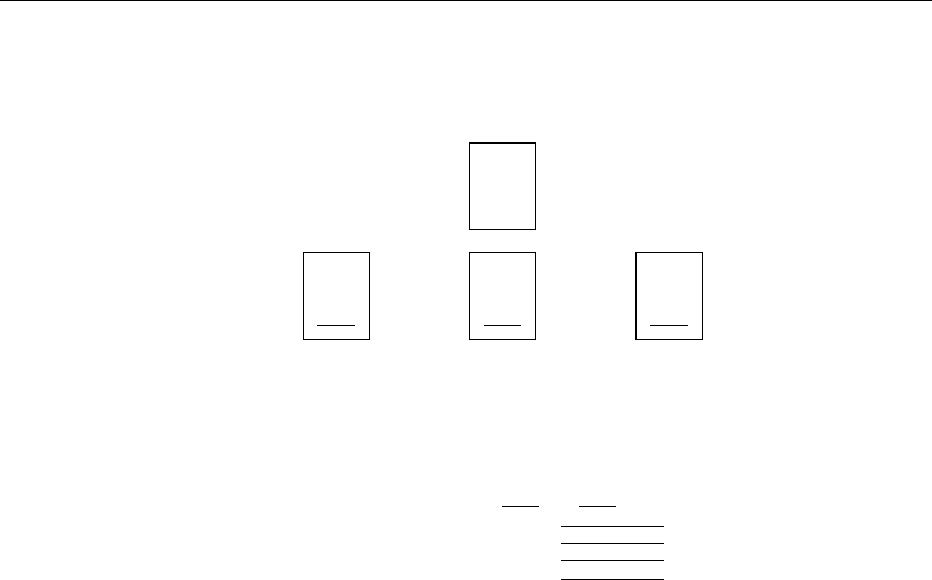

0023Method Magnitude estimation is a form of ratio

scaling where the perception of a specified attribute

in one sample is measured as a ratio of the perception

of that attribute in another sample. Stevens introduced

this method in 1953, and one of its first applications

in sensory analysis was to evaluate pleasantness of

odors.

0024There are two main methods of collecting ratio

data by this method. In the first method, one sample

is designated the standard and allocated a whole

positive (not zero) number (e.g., 100) to present the

perception of a specified attribute. The perception of

this attribute in subsequent samples is represented as

a fraction or multiple of the standard number. For

example, if the sample evaluated is twice as sweet as

the standard then it is allocated the value 200, if it is a

quarter as sweet than it is allocated the value 25. It is

often recommended that the standard sample should

be one-third of the way along in the range of samples

to be used in the experiment.

0025In the second method, the assessor allocates a posi-

tive (not zero) number to the first sample, and evalu-

ates the perception of that attribute in subsequent

samples as a ratio of the first sample. Whichever

approach is adopted, magnitude estimation usually

requires more training than the other methods of

VeryNot

Please taste the sample coded 563, and indicate how bitter it is by placing a vertical mark through the line below.

fig0005 Figure 5 Evaluation of the taste attribute bitter, using a continuous line scale.

5150 SENSORY EVALUATION/Sensory Rating and Scoring Methods

data collection. An example of a magnitude estima-

tion form is given in Figure 6.

0026 Data analysis Data collected on a ratio scale, by

magnitude estimation, require additional thought as

they have to be transformed before analysis. In con-

sidering data analysis, it is important to recall that the

data are ratios for each individual. Further, as each

individual may have used his or her own range within

the ratio scale, the distribution of the data will differ

from individual to individual. It is also likely that if an

individual’s data are plotted, the shape of the distri-

bution of data about the standard sample will differ

for each subject. Thus, not only are there scaling

problems to contend with, but there is also inconsist-

ency in the distributional plot of the data. For these

reasons, individual data cannot be assumed to come

from a normal distribution, and further direct aver-

aging of data would be misleading due to the scaling

problems. Thus, data are transformed to insure that

each individual has, in effect, used the same scale.

Several methods can be used to rescale magnitude

estimation data: modules equalization, modulus

normalization, and external calibration.

0027 Modules equalization requires that the ratings pro-

vided by each assessor are multiplied by a constant,

with the aim of insuring that the geometric mean of

each individual is the same as the geometric mean

of the grouped data. Modulus normalization is used

if many samples are evaluated over a number of

sessions, and the experimenter has built in common

samples that appear at each tasting session. The infor-

mation from the common samples is then used to

rescale the data based on the geometric mean.

0028 Averaging magnitude estimation data is not as

straightforward as interval data. However, these data

usually have a log-normal distribution and hence,

by taking the logarithms distribution of the data

becomes symmetric and hence more like a normal

distribution. It is often easier to analyze logarithmic

data. Parametric statistics, as described above, can

then be used to analyze transformed magnitude esti-

mation data if it is certain that the transformed data

are normally distributed; otherwise nonparametric

methods must be used.

Ranking

0029Ranking is neither a rating nor a scoring method, but

as it is widely used in sensory analysis and provides

ordinal data, it is included here for completeness. The

method of ranking is used to order a number of

samples according to increasing or decreasing percep-

tion of a specified attribute. Samples to be ranked

need to be presented at the same time, and this limits

the total number of samples that can be used in such a

test, due to sensory fatigue. Ranking of five or six

samples is often possible, although this number will

depend largely on the nature of the samples; for

example, chocolate has mouth-coating properties

that make it difficult to rank many samples. An

example of a ranking exercise is illustrated in

Figure 7. Data are analyzed using nonparametric

statistical methods, as described earlier in this article.

See also: Sensory Evaluation: Sensory Difference

Testing; Descriptive Analysis

Please taste the reference sample (R), and allocate it a value of 100 to represent

the sweetness intensity perceived

Please taste each of the three samples in the order indicated. You are required to

allocate each sample a number (not zero) indicating the degree to which it is

more or less sweet than the reference sample.

R

100

749 381 526

fig0006 Figure 6 Flavor assessment by magnitude estimation, where 100 represents the reference against which other samples are

evaluated.

Please taste the four samples of chocolate, and rank them

according to increasing intensity of cocoa flavor.

Rank Code

1

2

3

Least cocoa

4 Most cocoa

fig0007Figure 7 Flavor assessment by ranking, where the higher rank

represents higher intensity of cocoa flavor.

SENSORY EVALUATION/Sensory Rating and Scoring Methods 5151

Further Reading

Carpenter RP, Lyon DH and Hasdell TA (2000) Guidelines

for Sensory Analysis in Food Product Development and

Quality Control, 2nd edn. Maryland: Aspen.

Chatfield C and Collins AJ (1980) Introduction to Multi-

variate Analysis. London: Chapman and Hall.

ISO (1987). Sensory Analysis – Guidelines for the Use of

Quantitative Response Scales. ISO 4121. (new version

on draft.)

Land DG and Shepherd R (1988) Scaling and ranking

methods. In: Piggott JR (ed.) Sensory Analysis of

Foods. London: Elsevier.

Lawless HT and Heymann H (1998) Sensory Evaluation of

Food: Principles and Practices. New York: Chapman

and Hall.

Lebart L, Morineau A and Warwick KM (1984) Multi-

variate Descriptive Analysis: Correspondence Analysis

and Related Techniques for Large Matrices. New York:

Wiley.

Moskowitz HR (1977) Magnitude estimation. Notes on

what, when and why to use it. Journal of Food Quality

3: 195–228.

O’Mahony M (1986) Sensory Evaluation of Foods: Statis-

tical Methods and Procedures. New York: Marcel

Dekker.

Peryam DR and Giradot NF (1952) Advanced taste-test

method. Food Engineering 24: 58–61, 194.

Peryam D R and Pilgrim FJ (1957) Hedonic scale method for

measuring food preferences. Food Technology 11: 9–14.

Stevens SS (1953) On the brightness of lights and the loud-

ness of sounds. Science 118: 576.

Descriptive Analysis

H Stone and J L Sidel, Tragon Corporation, Redwood

City, CA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Descriptive analysis continues to attract interest and

applications in more and more companies as the

results from tests are discussed and used in support

of product market decisions. At the same time re-

search on new methods has been discussed, offering

the sensory professional a variety of options. As a

methodology, descriptive analysis is the most sophis-

ticated source of product information available in the

context of providing a complete and quantitative

word description of a product’s sensory characteris-

tics. Such information can be considered in the same

way as one considers chemical or biological informa-

tion about products. Because it is quantitative, it

provides a focus for development efforts; it provides

a basis for measuring the effects of a process or of

ingredients; i.e., establishing causal relationships

between ingredients, technology, and perceptions; it

provides a basis for linking consumer response behav-

ior to specific product characteristics, and for busi-

ness applications, identifying those product attributes

that are most important to consumer preferences.

Before discussing methodologies, it is necessary to

define what we mean by descriptive analysis.

0002Descriptive analysis is a sensory methodology that

provides quantitative word descriptions of products

based on perceptions verbalized by a group of quali-

fied subjects. It is a total sensory description, taking

into account all the sensations that are perceived –

visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory, kinesthetic –

when the product is evaluated. This evaluation

could include product handling and use at home, for

example, and in that sense, it is a more typical and

total experience. The evaluation could focus on a

single modality of a product, such as aroma or tex-

ture; however, there is considerable risk in such a

narrow focus, a risk that will be discussed later in

this article.

0003The earliest practitioners of descriptive analysis

were the brewmasters, perfumers, flavorists, and

other product specialists. Employers appreciated the

value of their information because they not only de-

scribed products and made recommendations about

the purchase of specific raw materials, they also

evaluated the effect of process variables on finished

product quality (as they determined product quality).

They also determined that a particular product met

their criteria (and that of their company) for manu-

facture and sale to the consumer. These activities

served as the basis for the foundation of sensory

evaluation as a science, although at the time it was

not considered within that context. It was possible for

the expert to be reasonably successful as long as the

marketplace was limited (i.e., less competitive and

regional in character). However, this changed with

the scientific and technical changes in consumer prod-

ucts industries and especially in the food and beverage

industry. Use of more sophisticated raw materials and

processes made it increasingly difficult for experts to

be as effective as in the past. The increasingly com-

petitive and international nature of the marketplace,

the rapid introduction and proliferation of new prod-

ucts, and the sophistication of the consumer’s palate

further challenged the expert’s ability to function as in

the past. During this time, new sensory test methods

and more sensitive scales were described along with

improved statistical procedures for the analysis of

responses. These developments enabled the sensory

professional to provide more precise product infor-

mation and participate more fully in product market

5152 SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis

decisions. Formal descriptive analysis (and the separ-

ation of the expert from sensory evaluation) received

its major impetus from ‘flavor profile,’ an approach

which demonstrated that it was possible to select and

train individuals to describe the sensory properties of

a product in some agreed sequence, leading to action-

able results without dependence on the individual

expert. The method was distinctive in that no direct

judgment was made concerning consumer acceptance

of the product, although most investigators assumed

consumer acceptance based on a result. The method

attracted considerable interest as well as controversy;

however, there was no question as to its importance

to the development of the field. Since then, other

methods have been developed, in part responding to

its limitations as well as developments in measure-

ment and human perception.

Background

0004 We begin this discussion by first focusing on the most

fundamental issues on which all descriptive methods

are based, i.e., the subject selection process, the abil-

ity of the subjects to verbalize perceptions, and their

ability to assign measures of strength (or intensity) to

those perceptions in a reliable manner. Implicit in this

statement is the recognition that each person is

unique in terms of sensory skills; different individuals

can be differentially sensitive to a sensation, more than

a single subject (the expert n of 1) and more than a

single judgment (from each person) is required for

each product evaluated. People exhibit variation in

their sensory skills and this variation reflects the state

of those individuals at the time of that judgment –

their physiology, attitudes, and motivation. Not only

are people different from each other, but they also

vary within themselves, from moment to moment,

from day to day, and so forth. This individual vari-

ation is one of the most critical aspects of the descrip-

tive process (and of all human response behavior) and

it is often conveniently ignored. This issue will be

discussed in more detail in subsequent sections; suf-

fice to say that it must be accounted for in any de-

scriptive test if results are to be believed, and to have

any hope of external validity and credibility with the

test requestor.

0005 This discussion is particularly important because,

in the course of organizing a descriptive panel, there

are numerous decisions made by the sensory profes-

sional (the panel leader) that determine the usefulness

of the results. These decision points and the actions

taken derive from the panel leader’s understanding of

(1) the perceptual process in general and (2) the spe-

cific descriptive process used. Unlike discrimination

and acceptance tests where subjects exhibit choice

behavior in a global sense, i.e., all perceptions are

taken into account to yield a single judgment, the

descriptive test requires each subject to provide nu-

merous judgments (one for each attribute) for each

product. These judgments can be influenced by the

instructions given to the subjects and the type and

extent of the training. Too much information/instruc-

tion can yield a result that reflects the panel leader’s

knowledge of the products and not the subjects’ per-

ceptions. Alternatively, too little information will

result in a lack of focus, as evidenced by greater

than expected variability and loss of product differ-

entiation.

0006Using the quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA)

methodology as a reference, various methods, such as

spectrum analysis, are described and contrasted.

Other methods are also mentioned; however, most

are modifications of the two previously mentioned.

Free-choice profiling, the one different method

requiring no subject selection and no training, has

undergone many changes such that it more closely

approximates the afore-mentioned methods and no

longer warrants separate consideration.

0007All descriptive methods share some common char-

acteristics as well as some differences and these will

be compared and contrasted in the following sections.

To understand better these similarities and differ-

ences, it is useful to think in terms of the steps involved

in the development of a descriptive panel capability.

These include four main activities: screening, training

or language development, data collection, analysis

and interpretation, and a fifth often overlooked

activity, panel performance.

Screening

0008A descriptive test typically involves relatively few

subjects (as few as 10 to as many as 20). Reliance

on so few subjects is possible provided there is good

evidence that the specific differences obtained are

reliable and valid, and not the result of spurious

responses from one or two insensitive or more vari-

able subjects. An effective means of minimizing this

latter problem is to screen the subjects for their sens-

ory skills before training. One can show that in any

population there is a wide range of sensory skills;

some individuals will be very sensitive and some will

be very insensitive (sometimes by as much as 100-fold

or more), and this skill can be product- and attribute-

specific. A goal of screening is to identify and excuse

from further testing those individuals who cannot

perceive product differences at better than chance –

those that are insensitive or so variable as to raise

doubt as to their participation in a test. Failure to

carry out adequate screening raises serious questions

SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis 5153

as to the quality of any sensory information obtained.

Empirically, we observe that individuals whose sens-

ory skills are not equal to or better than chance are

usually less sensitive and more variable than the

person who is sensitive and whose performance is

better than chance. This enables one to use the fewest

number of subjects without loss of information.

0009 There are differences in the approaches used for the

qualification of subjects, and panel leaders must

decide what procedure(s) they are willing to use. For

example, it has been recommended that screening for

food or beverage tests be based on sensitivity to par-

ticular chemicals (e.g., sweet, sour, salt, and bitter

stimuli or an identification of specific odorants) and/

or on various personality tests. It is surprising that

these types of sensitivity tests continue to be recom-

mended (as used in flavor profile and related

methods) in spite of earlier evidence that it had a

low correlation with a subject’s subsequent perform-

ance. The spectrum analysis method suggests using a

combination of threshold testing followed by discrim-

ination with actual products. Free-choice profiling

claimed subject screening was not necessary and

atypical responses would be dealt with by statistical

means.

0010 In QDA, the discrimination methodology is the

screening method of choice. It is preceded by deter-

mining that the participant uses and likes the prod-

ucts that will be tested. Regular users of a product are

more sensitive to differences in those products (e.g.,

compared to the infrequent user). The discrimination

model is very effective for establishing the level of

sensory skill among products that will be tested. It is

also the most parsimonious in terms of time required

to establish the level of skill. Based on results of 20–

30 discrimination trials completed over 3 or 4 days

(daily sessions last about 90 min), one can identify

discriminators from amongst a group of totally

naive individuals. The trials themselves encompass

all the modalities that are expected to be involved,

and the pairs of products are made progressively

more difficult. Working with qualified subjects, ex-

tensive screening tests are not needed unless there is

evidence that some subjects exhibited decreased sen-

sitivity in a previous test, or one is using an entirely

different product category, and again, there is reason

to believe that such screening is warranted. Screening

has several objectives: first, it identifies the less sensi-

tive, more variable subject; second, it familiarizes

the subjects with the sensory characteristics of the

products; and third, it identifies any individuals who

have difficulty following instructions. However, there

are no guarantees, and it is only after data collection

that one can empirically determine the effectiveness

of the screening and subsequent training activities.

0011This screening procedure is intended to be product-

or category-specific, as is the subsequent training

effort. For example, if one were testing Cheddar

cheeses, then screening would use samples of Cheddar

cheeses, and preferably those that will be tested, and

not other foods or unrelated ingredients or specific

chemicals. This does not mean that subjects are

product-specific, rather that screening should be of

the products that will be tested or used during the

language sessions. This should not be construed to

mean that one must qualify subjects every time a

different set of products is evaluated. Most subjects

are capable of meeting the qualifying criteria for many

different categories of products. Experienced subjects

(e.g., those who have participated in at least one test

within the past 1 or 2 months) will have learned how

to use their senses and how to evaluate products

within a category being evaluated without a signifi-

cant loss of sensitivity, and are therefore very likely to

be able to evaluate products beyond those for which

they were screened. The panel leader makes this deci-

sion based on the existing subject performance data.

0012Screening subjects for more than one type of prod-

uct makes sense provided the tests will follow one

another with minimal delay. It will eliminate the

need to initiate any additional screening before the

next test. This does not guarantee that a subject will

stay qualified, nor does it eliminate the need for the

other stages of training. In addition, it does not

excuse the panel leader from monitoring subject per-

formance before the next test. Infrequent use of sub-

jects, e.g., no testing for 3 or more weeks, may require

that some screening is necessary, in which case much

of the earlier effort will have been wasted. A potential

problem with screening subjects on several products

is the assumption that these individuals will be willing

to participate in future tests. If used too frequently

(e.g., daily) there is every likelihood that the subjects

will lose interest and thus not perform satisfactorily.

It may be better to develop a larger pool of qualified

subjects and reduce reliance on a small subset of

people for all testing, or qualify small groups for

each category depending on the anticipated need

for the product information. Panel leaders must de-

velop guidelines for subject use based on their com-

pany experiences and not blindly follow an external

practice.

0013In summary, it is necessary that subjects for a de-

scriptive test demonstrate their ability to perceive

differences at better than chance among the products

that they will be testing. This will be insured if prod-

ucts used are representative of the products that will

be tested. As a guide in selecting subjects we have

used a minimum of 65% correct across all discrimin-

ation trials with greater emphasis placed on those

5154 SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis

pairings that were more difficult. However, there

have been situations in which the number of subjects

meeting this criterion is not sufficient and it is neces-

sary to lower this percent. In some instances an indi-

vidual has been selected whose performance has been

as low as 50%. This latter situation would be atyp-

ical, one which would be a decision of the panel

leader. It is important to keep in mind that screening

cannot guarantee subsequent performance; however,

there is no doubt that individuals whose skill is less

than chance do not perform well (in descriptive tests).

Over many thousands of such tests we have observed

that about 30% of those who volunteer will fail to

meet these performance criteria. This particular point

has implications that extend well beyond descriptive

testing.

Training

0014 Training is initiated directly after screening and it is

here that one also encounters different approaches.

While the training process is usually focused on the

language (or attributes) used as a basis for scoring the

products, there are other equally important activities.

These include grouping attributes by modality,

ordering them by occurrence within a modality, de-

veloping definitions for each attribute, familiarizing

subjects with scoring the attributes, and identifying

references that are helpful in training. Inexperienced

subjects starting with a new set of products (and no

list of attributes) will need about 7–10 h of training.

For this same panel and an existing language, the time

is reduced to about 6–7 h. Experienced subjects usu-

ally need about 5–6 h when presented with an entirely

new product category. These training times are

intended solely as a guide, as the products and the

skill of the panel leader will also have an effect.

Regardless of the situation, the subjects work, at

times individually but mostly as a group, to insure

that the attributes are sufficiently understood by one

another, and that all of the product’s characteristics

have been fully accounted for. All of this is done

under the direction of a panel leader who does not

participate in developing the language. The QDA

method was the first method and remains one of the

few that excluded the panel leader from directly con-

tributing attributes in language development. This is

true whether one is working with an experienced

panel or with a panel that has never participated

before. The panel leader’s primary responsibility is

to facilitate communications among subjects and

organize results of their discussion. Participating as

a subject (as is allowed with the spectrum method)

is not recommended because of bias related to

one’s awareness of product differences and the test

objectives. Not only does this action communicate

the wrong message to the subjects (subjects will tend

to defer to the panel leader, whom they assume has

the correct answer), but also the end result is more

likely to be a group judgment rather than a group of

judgments.

0015Developing a sensory language or using one that

already exists is an interesting process and certainly

one that is essential for the successful outcome of a

test. For some, the language assumes almost mystical

importance, such that a considerable body of litera-

ture has been developed in which lists of words (lexi-

cons) are published for specific types of products.

Implicit in use of an agreed list is the assumption of

universality, i.e., panels in different parts of the world

would yield the same result by using the same lan-

guage. It appears that many of these lists were pre-

pared by technologists and sensory professionals by

consensus. Unfortunately, this is not very different

from the efforts of product specialists or experts of

50 or more years ago when they developed quality

scales and corresponding descriptions for products as

part of an effort to establish food quality standards.

Besides their interest in evaluation of their respective

company’s products, their technical and trade associ-

ations often formed committees for the express pur-

pose of developing a common language for describing

the flavor (or odor) of the particular category of

products. For purposes of this discussion we chose

the publication by Clapperton et al. (1975) on beer

flavor terminology as an example of the efforts (of the

association of brewers) to develop an internationally

agreed terminology. These authors stated the purpose

as follows: ‘to allow flavor impressions to be de-

scribed objectively and in precise terms.’ Various lit-

erature and professional sources were screened for

words (or descriptors) describing the flavor of beer,

and, after reviews, the committee arrived at an agreed

list. As the authors noted, the issue of chemical names

compared with general descriptive terms was resolved

by the inclusion of both.

0016From a technical viewpoint, the use of chemical

names was appealing because it was believed that

they could be related directly to specific chemicals in

the beer. An example would be the term ‘diacetyl,’

which could be ascribed to a specific chemical, as

compared with ‘buttery,’ a less precise term that

might be ascribed to several chemicals. By including

both types of terms it was stated that the terminology

would be of value to the flavor specialist (the expert)

and the layperson (the consumer). While the concept

of an agreed terminology should have considerable

appeal, careful consideration of this approach reveals

significant limitations, especially in relation to its

application beyond that technical panel. After all,

SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis 5155

the words used to describe sensations are nothing

more than labels to represent sensations – no causal-

ity is inferred. It is risky to decide a priori what

word(s) subjects should use to describe a particular

sensation, or still greater risk that naive consumers

will understand them. Recall that about 30% of any

population of consumers cannot differentiate prod-

ucts at least at chance. In addition, subjects will not

be equally sensitive to all sensations. Some sensations

are complex, and in all likelihood subjects will want

to use more than a single word to represent that

experience. The fact that product changes based on

formulation, process, or both rarely yield a single

sensation means that, for example, a flavor change

would not be totally represented. To restrict subjects

to specific words assumes that the language is

unchanging, as are the meanings assigned to it, and

that all subjects will associate a specific word to a

specific sensation. The frame of reference for an attri-

bute is unique to each subject, and attributes requir-

ing a very different frame of reference are difficult for

inexperienced and/or nontechnical subjects to under-

stand. While chemical terminology is supposed to

have specific meaning to an expert, it is unlikely to

have the same meaning to a consumer, to a trained

subject, or to another expert.

0017 It should be noted that the use of technical termin-

ology extends training time and this appears to be

related to the complex nature of this terminology,

especially for subjects with no technical training.

The spectrum method provides the subjects with at-

tributes, as well as references and designated intensity

scores for those references, all of which are intended

to enhance the testing process. The use of standard or

previously specified attributes and references implies

that product variables will not produce unique sensa-

tions, that references themselves are not variable, and

forces subjects to limit the value of their perceptions

relative to what has been perceived in the past by

others. The training effort is extended over a period

of 3 months; this raises questions as to its responsive-

ness and overlooks the inherent variability in the

subjects (over time) and the references that are being

used (that also change over time). Regardless of

the source, a language that does not provide for

subject input is unlikely to yield uncomplicated sens-

ory responses. Subjects are influenced by the infor-

mation given to them, and are much less likely to

question it, because of its source. While it can be

argued that such approaches are merely intended to

help panel leaders and the subjects, the temptation is

very strong to use this approach rather than allowing

subjects to use their own terminology and, most

important, to allow subjects to express what they

perceive.

0018To the student of the history of psychology, descrip-

tive analysis can be considered as a form of introspec-

tion, a methodology used by the school of psychology

known as structuralism in its study of the human

experience. Structuralism required the use of highly

trained observers in a controlled situation verbalizing

their conscious experience (the method of introspec-

tion). Of particular interest to us is the use of the

method of introspection as an integral part of

the descriptive analysis process and, specifically, the

language development component.

0019However, the obvious difference is that products

are included (in descriptive analysis) so that the sub-

ject’s responses are perceptual and not conceptual.

Subjects are encouraged to use any words, provided

that they explain to the other members of the panel

what they mean – they define the meaning of each

word-sensation experience. The goal is for the panel,

by consensus, to associate a particular sensation with

a particular word or group of words. While each

subject begins with his or her own set of words, they

work as a group to come to agreement as to the

meaning of those words, i.e., the definitions or ex-

planations for each word-sensation experience, and

also when they (the sensations) occur. In addition,

they also develop a standard evaluation procedure.

All of these activities require time; in the QDA meth-

odology, there can be as many as five consecutive

daily sessions, each lasting about 90 min. This

amount of time is essential if the sensory language is

to be developed and understood, and the subjects are

capable of using it (and the scale) to differentiate the

products. These sessions help to identify the word-

attributes that could be misunderstood, and also

enable the subjects to practice scoring products and

discussing results, on an attribute-by-attribute basis.

Of course, all this effort cannot make subjects equally

sensitive to all attributes. In fact, subjects rarely, if

ever, achieve complete agreement for all attributes,

nor are subjects equally sensitive to all attributes, nor

should it be expected (if this did occur, one could rely

on the n of 1). The effectiveness of the training pro-

cess can be determined only after a test, after each

subject has scored products on a repeated trial basis

and the data have been analyzed. The idea that there

should be a specific number of attributes is, at best,

questionable, as is the issue of whether or not one has

the correct attributes. How does one know that all

the attributes have been developed or that they are

the right ones? The answer to the former is empirical

(and in part answered in much the same way as one

determines the number of angels that can occupy the

head of a pin). The answer to the latter is also empir-

ical, i.e., given a set of variables, do some attributes

exhibit systematic changes as a function of those

5156 SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis