Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

variables? Other methods, including free-choice pro-

filing, claim that no training is required; subjects can

use any words they want and the results are collated

for analysis. However, the ‘no training’ is not neces-

sarily correct in the sense that researchers describe the

time and effort required by the subjects to develop

definitions for the words; in more recent publications

on use of the method, as many as 10 training sessions

are used. Clearly, there are wide differences in what

is meant by training as concerns these different

methods.

0020 The words used to represent sensations are nothing

more than labels. There is no reason to assume that

these words represent anything beyond that – no

causality is inferred. Without an appropriate design

study any idea as to the external validity of a specific

word is hypothetical, at best. Some researchers sug-

gested that the words represent concepts, and that for

a descriptive panel to be effective, concepts must be

aligned, i.e., subjects must agree on all the sensations

(or attributes that represent those sensations) to be

included in a concept if the results are to be useful.

Unfortunately this idea of concept alignment remains

to be more clearly delineated before one can deter-

mine its relevance to the descriptive process. One

could propose that the process by which subjects

discuss their judgments for an attribute, and the def-

inition for that attribute, represent concept align-

ment, which is an integral part of the QDA training

process. Whether this, in fact, is concept alignment

remains to be demonstrated; however, it is clear that

most subjects can reach sufficient agreement on

attributes and can reliably differentiate amongst

products, after completion of training. How attri-

butes are formulated in the brain and the true

meaning of those attributes are issues that go well

beyond descriptive analysis and sensory evaluation,

in general.

0021 One should remember that subjects are not likely

to agree totally on all the sensations to be included,

any more than there is agreement on all the attributes.

The sensations are themselves complex and inter-

active, leading to multiple words to represent them.

The individuality of each subject (sensitivity, motiv-

ation, and personality) further complicates or adds to

the complexity of the process. As a result, a descrip-

tive panel typically develops many more attributes

(30 or 40 or more) than will be necessary to describe

an array of products fully. The fact that there are

many more attributes than are needed should not be

unexpected or of concern. This reflects the unique-

ness of the individual and the inherent imperfections

of the perceptual process, or at least the ability

to verbalize more precisely and/or capture those

perceptions.

0022In addition to a descriptive language and defin-

itions, it may be useful to have references available

for training or retraining subjects. Here, too, one

finds different opinions as to the types of references

and how they are to be used. For example, a compre-

hensive list of references and how they are to be used

may be presented, including their respective intensity

scores for scale extremes. Unfortunately, these refer-

ences are based on commercially available products,

all of which are variable in the normal course of

production, in addition to the intended changes

based on changing technologies, ingredients, and/or

market considerations. Over time, references will

change which can influence subjects in unanticipated

ways, further changing responses to product charac-

teristics. What, then, is the value of such references?

They have a role to play in helping subjects relate to a

particular sensation that is not easily detected or not

easily described. However, references should not

introduce any additional sensory interaction or fa-

tigue, or significantly increase training time. In most

training (or retraining) situations, the most helpful

references are usually a product’s raw materials. Of

course, there will be situations in which totally unre-

lated materials will prove helpful to some subjects,

and it is the panel leader’s responsibility to obtain

such materials. There will also be situations in

which no reference can be found within a reasonable

time period. A panel leader should not delay training

just because a reference cannot be found. While most

professionals agree that references are helpful, there is

no evidence that without them a panel cannot func-

tion or that results are unreliable and/or invalid. We

have observed that so-called expert languages usually

require numerous references, and subjects take con-

siderably longer to learn (this language) than they do

a language developed by themselves. This should not

be surprising, if one thinks about it. After all, refer-

ences are themselves a source of variability; they

introduce other attributes unrelated to their purpose,

they are out of context for the complete product, and

increase the potential for sensory interactions. The

panel leader must therefore consider their use with

appreciation for their value as well as for their limita-

tions, and must decide when and what references will

be used. In our experience they are of limited value,

for use in the language development and training or

retraining activities. In retraining, or when adding

new subjects to a panel, they are helpful in enabling

these individuals to experience what the other sub-

jects are talking about and possibly to add their com-

ments to the language.

0023Some methods make great use of references, while

others do so on an ad hoc basis, i.e., they use them

only when they are helpful to the subjects.

SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis 5157

Scoring

0024 Most methods today are presented as quantitative,

relying on various types of scales. The QDA method-

ology makes use of a line scale (a graphic rating scale)

and the concept of functional measurement to obtain

intensity judgments. The scale is a 15-cm line with

two vertical lines, each placed 1.27 cm from the scale

ends. Below each of the vertical lines are words that

designate scale direction and intensity for that attri-

bute. For the scale to be used effectively, the subjects

must be provided with ample opportunity to practice

scoring products and become comfortable with using

the scale and with the range of product sensory char-

acteristics. This latter point is especially important to

the successful use of the scale. In the training no

attempt is made to require subjects to use the same

part of a scale, only that each subject be consistent

with him- or herself. Because each product is scored

on a repeated-trials basis by each subject, it makes

little difference what part of the scale is used to differ-

entiate the products. This use of a single scale is in

contrast with those methods, in which more than one

type of scale may be used. One type of scale is the

difference from reference scale in which an identified

product is provided with a designation as to its scale

location, and products are scored relative to that

standard. This type of scale is popular but is flawed

as the reference itself will vary, requiring subjects

to alter their perceptions (and responses) in rela-

tion to the variability associated with it. Most

methods are now using some type of line scale but it

is not clear as to whether a context is provided during

training.

Design and Analysis

0025 The design and analysis of a descriptive test are

equally important for a successful outcome. A de-

scriptive test yields a large sensory database (in com-

parison with a discrimination or an acceptance test),

often yielding 10 000 or more data points. There are

usually both univariate and multivariate components,

and as such, it permits a wide range of statistical

analyses. One of the main features of the QDA meth-

odology was the use of a comprehensive statistical

analysis of the data, which represented a significant

development for sensory evaluation. With the avail-

ability of statistical packages and the power of per-

sonal computers, panel leaders have unlimited and

low-cost resources, providing an online capability

for obtaining means, variance measures, ranks

and pairwise correlations, and for factor analysis,

multiple regression, cluster analysis, discriminant

analysis, etc.

0026All descriptive methods espouse the use of replica-

tion (repeated trials); but only the QDA method

appears to use it for all test situations. The extent of

replication is a decision that the panel leader makes

based on the products, the expected degree of diffi-

culty, and past experience of the panel. For QDA a

maximum of four replicates is usually sufficient. With

more replication, to six, eight, or more, there may

be a decreasing return as the number of replicates

increases versus the amount of time required for the

subject to complete all the evaluations versus statis-

tical power. Empirically we have not found decision

changes as a result of increasing replication beyond

four. As the number of products evaluated is in-

creased beyond 10, one has the option of decreasing

replication to three, taking advantage of the total

number of evaluations. These are panel leader deci-

sions; there are no rules as to how many replicates is

necessary. The decision takes into account past test

history with the product, expected product variation

based on manufacturing experience, and so forth.

Experience has shown that three to four replicates

are usually sufficient.

0027The analysis of variance with replication model is a

very powerful and robust system for descriptive data

and is the core method with QDA; other parametric

and nonparametric algorithms are also used. With

repeated trials one is more likely to yield significant

product differences. In addition, this design provides

a basis for measuring and visually examining subject

performance on an individual attribute basis. Other

descriptive methods neither specify these kinds of

analyses or make use of programs with defaults that

remove some judgments without the researcher

knowing what has happened. One such program,

Procrustes Analysis, eliminates data based on a test

for outliers; while mathematically correct, it takes no

account of whether it is a true perception. Many

consider its use as experimental and too risky for

everyday use.

0028All sensory data need to be analyzed in some detail

as a basis on which to reach conclusions about prod-

uct differences. As noted before, the descriptive test

uses a limited number of subjects and one must be

very confident about their behavior before one initi-

ates any extrapolations or investigations about the

underlying structure of the data. Specifically, replica-

tion provides a basis for determining the skill of each

subject and of the panel which increases the confi-

dence of all product decisions. It is an essential cost

that cannot be forfeited without serious compromises

in any conclusions that are reached about results.

0029As noted previously, in QDA, there are parametric

and nonparametric procedures to identify subjects

and attributes for which sensitivity is reduced and/or

5158 SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis

there is a significant interaction. This information has

several applications. First it provides the panel leader

with specific information about a subject’s response

behavior for each attribute relative to the panel’s.

Second, it identifies whether a subject is a significant

source of interaction and the type of interaction.

Crossover interaction is the more serious type (versus

magnitude) and with the appropriate nonparametric

procedure, one can easily determine a subject’s rank

order compared with the panel rank order. This pro-

cess focuses the panel leader’s attention on those sub-

jects who exhibited this response behavior, as well as

on that individual’s scale use. This kind of informa-

tion can be displayed numerically as well as graphic-

ally, along with other types of subject performance

behavior, e.g., discriminant functions. For the panel

leader, this information is very useful in determining

the quality of the results. However, the value to the

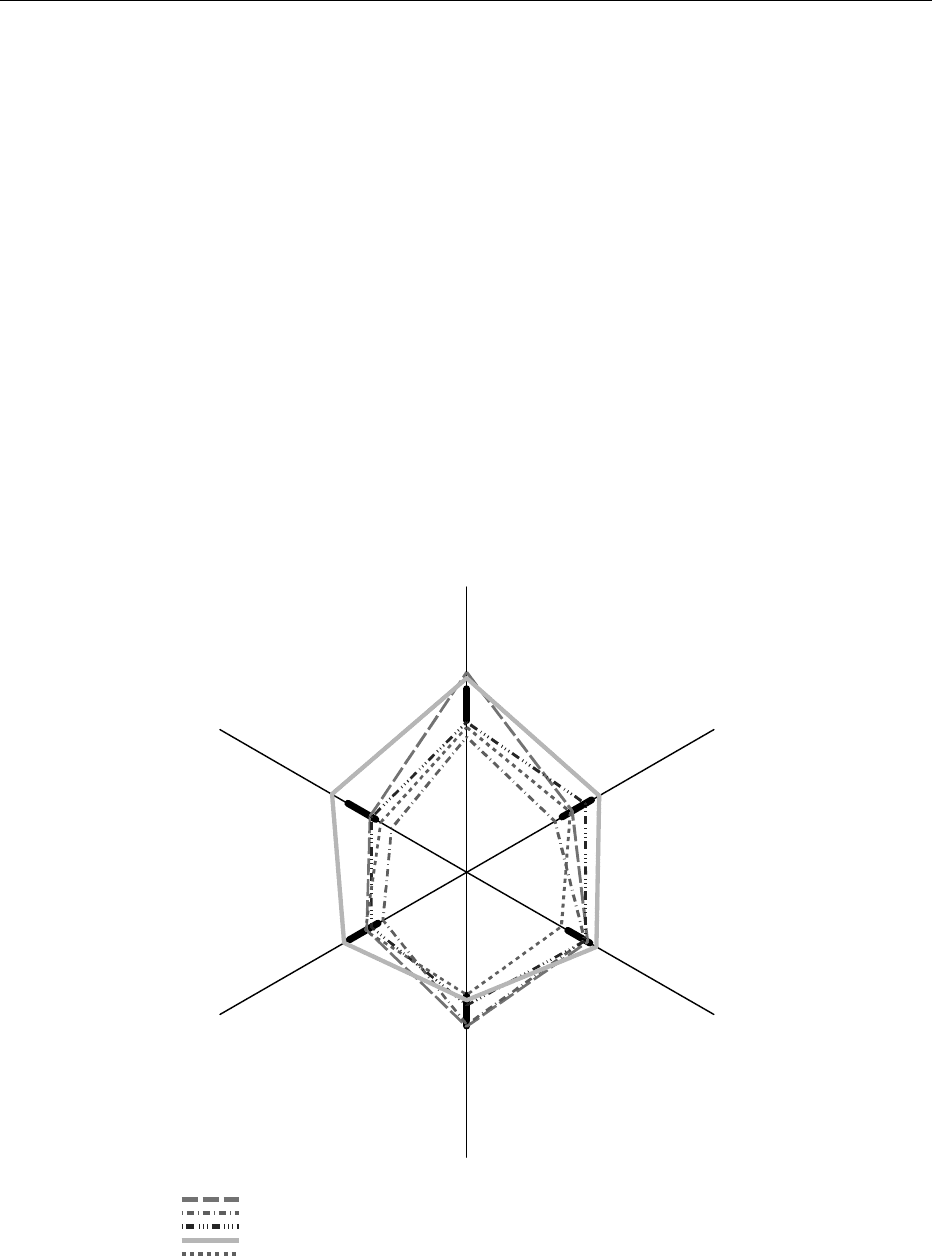

user rests with product differentiation, and the easiest

way of demonstrating this is through the use of plots

such as the one shown in Figure 1, a typical ‘spider’

plot for some of the mouth-feel attributes. Also

included is the LSD (a black bar) for each attribute.

The mean intensity score for each attribute is deter-

mined from measuring the distance from the center to

that point at which the product bisects the line. With

today’s technology, these results can also be displayed

in a variety of ways; for example, displaying only the

most discriminating attributes based on a discrimin-

ant analysis, and so forth.

0030As with any readily available resource, statistics are

often misunderstood and/or misused, particularly

when responses are highly variable or when the

panel leader confuses use of some of the multivariate

procedures with evidence of the validity of results. In

other instances, investigators use factor analysis and/

or clustering techniques as a basis for excluding sub-

jects who are not in agreement with the panel or

to eliminate attributes that they believe are not

being used to differentiate products or are used as

Body Mf

Biting Mf

Warm Mf

Smooth Mf

Puckery Mf

Chalky Coating

Wine B

Wine D

Wine G

Wine K

Wine L

fig0001 Figure 1 Typical ‘spider’ plot for selected mouth-feel attributes. Intensity scores are measured from the center out to that point

where the product crosses. The attributes are spaced equally around the center point. Bars on the spokes represent the magnitude of

difference for that attribute to be significant using the least significant difference (LSD Mf, mouth feel).

SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis 5159

substitutes for the same sensation. These have been

proposed for use during training to reduce the

number of attributes on the score card (from 45 to

12) or the number of subjects. One must be careful

about using procedures that, a priori, decide which

subjects or attributes will be used. After all, the sub-

jects are still in training and to have them score prod-

ucts and use the results as a basis for reducing either,

or both, may be premature. This approach can lead to

a group of subjects who are more likely to agree with

each other, but how does one know that those who

agree are correct? How does one differentiate subjects

who are discriminators from nondiscriminators if, for

example, the nondiscrimination is of 30% or 40% of

the attributes? One of several objectives of training is

to enable subjects to learn how to evaluate products

using the attributes that they determined were helpful

to them (at that stage of the training). To proceed

from one session to another and substantially reduce

the list of attributes is communicating a message that

there is a correct list of words and, with a little

patience, it will be provided. Using factor analysis to

reduce the number of attributes during training is

troublesome because it assumes that attributes highly

correlated to a factor are measuring the same com-

ponent of the product and, therefore, one or two

attributes can represent the others. However, attri-

butes correlated to a factor are only an indication of

some common basis which assigns those attributes to

that factor; it does not imply causality. It is interesting

to note that one goes to considerable effort to encour-

age subjects to contribute words to use in a score card

and then to devise procedures to eliminate about 75–

80% of them before the actual test is performed, thus

sending the message to subjects that there is a correct

list. As mentioned previously, not all subjects will use

all the attributes to the same extent in differentiating

products, and eliminating too many of them substan-

tially increases the likelihood of reducing sensitivity

and overlooking product differences (an example of

type 2 error).

0031 After a test one should use univariate and multi-

variate procedures to help identify subjects who are

experiencing difficulty with specific attributes and/or

with use of the scale. This information is then used

prior to the start of the next test so as to clarify further

the testing process.

Conclusions

0032 Descriptive methods are an established methodology

recommended for all sensory programs. Results from

a descriptive test provide precise quantitative descrip-

tions of products, and this information has many

applications that range from product development,

to establishing relationships between ingredients and

sensory characteristics, to advertising claims.

0033In the past decade much attention has been directed

to the development of methods that provide the

sensory professional with alternatives on how a test

is organized and fielded, and how results are ana-

lyzed. There are currently two very different ap-

proaches described in the literature about the

organization and operation of a trained panel. One

takes an expert approach, relying primarily on thresh-

olds, and identification of specific flavors and odors

(flavor profile) while the other seeks to identify sub-

jects based on their sensory skill with the products of

interest. The former takes several weeks, while the

latter takes 3–5 days.

0034For training, one method begins by focusing on

single modalities with language obtained from a list

and subjects must learn to respond to those attributes,

while the QDA methodology requires that subjects

develop the list of words, the order within a modality,

the definitions, and the evaluation procedure. No

standards are used in this training. While the former

takes more than 8 weeks, the QDA completes these

activities in about 7–10 h for a totally new panel and

half or less this time for an experienced panel.

0035For data collection, QDA recommends a total of

four replicates, while the spectrum method indicates

that replication is appropriate without further discus-

sion as to how much or in what way the data will be

used. It is clear that those who have used these

methodologies and those who will use them in the

future will make their own modifications.

0036Data analysis is particularly important for deter-

mining the quality of the basic information. While

current interest is very high in the use of clustering

techniques and other multivariate procedures, such

analyses should be considered only after the quality

of the database has been assessed.

0037For the sensory professional there is much to choose

from when considering a descriptive test. Whatever

methodology is chosen, there are many aspects that

require decisions from the professional. It is the

authors’ contention that these decisions should be

influenced by the following considerations:

1.

0038All subjects should be screened for their sensory

skill using products from the category being

tested.

2.

0039About 30% of the people who volunteer to

participate in these screening tests will not meet

minimum requirements of at least 50% correct

matches (in a discrimination test).

3.

0040Subjects should use words that are derived

from common, everyday language to describe

products.

5160 SENSORY EVALUATION/Descriptive Analysis

4.0041 Subjects should practice scoring products using

the afore-mentioned words as part of the training

effort.

5.

0042 Subjects should develop definitions or, if using a

previously developed score card, they should have

the opportunity to modify the definitions.

6.

0043 Subjects should score each product on a repeated-

trials basis with four replicates recommended.

7.

0044 Data analysis must provide measures of subject

reliability on an attribute basis, means and variance

measures for products, and tests for significance.

8.

0045 Multivariate procedures should be used where the

data warrant the effort.

0046 Sensory evaluation has achieved considerable rec-

ognition as a source of unique product information.

Much of this derives from the use of descriptive

analysis methods. This discussion is intended as a

perspective of the development and use of descriptive

analysis, as well as a review of the main features of

methods currently in use.

See also: Sensory Evaluation: Practical Considerations;

Sensory Difference Testing; Sensory Rating and Scoring

Methods

Further Reading

Boring EG (1950) A History of Experimental Psychology,

2nd edn. New York: Appleton.

Cairncross WE and Sjo

¨

strom LB (1950) Flavor profile –

a new approach to flavor problems. Food Technology

4: 308–311.

Caul JR (1957) The profile method of flavor analysis.

Advances in Food Research 7: 1–40.

Civille GV and Lawless HJ (1986) The importance of

language in describing perceptions. Journal of Sensory

Studies 1: 203–215.

Clapperton JR, Dalgliesh CE and Meilgaard MC (1975)

Progress towards an international system of beer flavor

terminology. Master Brewers Association of America.

Technical Quarterly 12: 273–280.

Harper RM (1972) Human Senses in Action. Edinburgh:

Churchill Livingstone.

Huitson A (1989) Problems with Procrustes analysis.

Journal of Applied Statistics 16: 39–45.

Ishii R and O’Mahony M (1990) Group taste concept

measurement: verbal and physical definition of the

umami taste concept for Japanese and Americans. Jour-

nal of Sensory Studies 4: 215–227.

Jones FN (1958) Prerequisites for test environment. In:

Little AD (ed.) Flavor Research and Food Acceptance,

pp. 107–111. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Lawless HT and Heymann H (1998) Sensory Evaluation:

Principles and Practices. Chapman and Hall, New York.

Lyon BG (1987) Development of chicken flavor descriptive

attribute terms aided by multivariate statistical proced-

ures. Journal of Sensory Studies 1: 99–104.

Mackey AO and Jones P (1954) Selection of members of a

food tasting panel: discernment of primary tastes in

water solution compared with judging ability for foods.

Food Technology 8: 527–530.

Marshall RJ and Kirby SPJ (1988) Sensory measurement of

food texture by free-choice profiling. Journal of Sensory

Studies 3: 63–80.

Marx MH and Hillix WA (1963) Systems and Theories in

Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Meilgaard M, Civille GV and Carr BT (1991) Sensory

Evaluation Techniques. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Mun

˜

oz AM (1986) Development and application of texture

reference scales. Journal of Sensory Studies 1: 55–83.

O’Mahony M, Rothman L, Ellison T, Shaw D and Bureau L

(1990) Taste descriptive analysis: concept formation,

alignment and appropriateness. Journal of Sensory

Studies 5: 71–103.

Powers JJ (1988) Current practices and applications of

descriptive methods. In: Piggott JR (ed.) Sensory Analy-

sis of Foods, 2nd edn, pp. 187–266. London: Elsevier

Applied Science.

Rainey BA (1986) Importance of reference standards in

training panelists. Journal of Sensory Studies 1: 149–154.

Smith GL (1988) Statistical analysis of sensory data. In:

Piggott JR (ed.) Sensory Analysis of Foods, 2nd edn,

pp. 335–379. Essex: Elsevier Science Publishers.

Stone H (1999) Sensory evaluation: science and mythology.

Food Technology 53: 124.

Stone H and Sidel JL (1992) Sensory Evaluation Practices,

2nd edn. Orlando, Florida: Academic Press.

Stone H and Sidel JL (1998) Quantitative descriptive

analysis: developments, applications, and the future.

Food Technology 52: 48–52.

Stone H, Sidel J, Oliver S, Woolsey A and Singleton RC

(1974) Sensory evaluation by quantitative descriptive

analysis. Food Technology 28: 24.

Williams AA and Arnold GM (1985) A comparison of the

aromas of six coffees characterized by conventional

profiling, free-choice profiling and similarity scaling

methods. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture

36: 204–214.

Williams AA and Langron SP (1984) The use of free-choice

profiling for the evaluation of commercial ports. Journal

of the Science of Food and Agriculture 35: 558–568.

Appearance

D B MacDougall, The University of Reading,

Reading, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001Of the five human senses, vision has had probably the

longest research into its mechanisms and is the best

understood of the five. Human eyes have a vast ability

SENSORY EVALUATION/Appearance 5161

to detect and process external information for the

brain to translate instantaneously into the percep-

tions of appearance and color. The appearance of

any object or scene can be defined as the response of

the observer to the totality of information that is

perceived by the eyes. Because the mechanism of

visual perception is complex, it can be divided into

several interacting components, which, when taken

together, are usually described as total appearance.

Undoubtedly, the most important of these compon-

ents is the perception of color. Most of this article will

deal with the way human visual signals are perceived

and how color is measured. However, a broader clas-

sification of the components that comprise total ap-

pearance would divide them into the physical and

chemical nature of the object and the influences of

the illumination and surroundings on the object’s

appearance. Additionally, for food, it must also in-

clude the social and psychological factors associated

with the consumer such as culture, food habits and

preference. The judgment of food appearance at the

point of purchase is related to the potential satisfac-

tion of the product coupled with its value. Such deci-

sions are usually made quickly with the criterion that

rejection may be more related to the presence of faults

in the food’s appearance than to what is regarded as

normally acceptable. The success of the food industry

in making consistent and attractive products depends

on the consumer’s continuing confidence that the

appearance of the product is a true indicator of

the subsequent acceptability of the eating quality of

the product. That is, the appearance and color of the

product are likely to be related in the consumer’s

mind with a value judgment of the other sensory

attributes and their expected satisfaction.

The Visual Process

0002 Vision is the property of the response of the eye to the

stimulus of light, as interpreted by the brain. Human

vision is binocular, i.e., objects are seen as solids in

perspective space. The appearance of any object in a

scene can be defined as the recognition of the proper-

ties of that object, i.e., size, geometry, solidity, surface

characteristics, and subsurface optical properties, i.e.,

transmission, opacity, or degree of translucence and,

most importantly, color. The visual process leading to

the recognition of appearance, as with all sensory

events, consists of a rapidly occurring sequence of

steps such that the observer sees the response to the

stimulus near instantaneously. Three factors are in-

volved in vision: sufficient light to illuminate the

object, human eyes with their complex detecting

mechanism and the object itself with its inter-

action with the incident light and the background

surroundings. Human eyes are virtually spherical,

approximately 2 cm in diameter, with six muscles to

control their mobility to give each eye a near circular

field of view. Light is detected after entering the iris,

which self-adjusts for light intensity. It is then focused

through the eye’s lens on to the retina with its two

types of light-sensitive cells, the rods and cones. This

results in a distinct image of the object being focused

on to the retina. Most of the retina is sensitive to low

levels of light, detected by the rods whose response is

noncolored and is known as ‘scotoptic vision.’ The

cones located in a small spot, approximately 2 mm in

diameter, centrally located in the retina and known as

the fovia, detect photoptic or color vision. In a person

with normal color vision, i.e., one who is not color

blind, there are three types of cones whose light-

detecting ability is wavelength-dependent. The mech-

anism of light detection in the photoreceptor cells

is by a conformational change in the photopigment

molecule rhodopsin, producing an electrical poten-

tial for amplification and transmission via a nerve

fiber to the brain. It is important to emphasize that

the perception of an object’s color and appearance

exists in the observer’s brain and not in the object

itself.

0003The wavelengths of maximum sensitivity of the so-

called blue (B) detecting cones is at 440 nm, that of

the green cones (G) at 540 nm and for the red cones

(R) it is at 600 nm. The G and R detecting bands

overlap equally at 580 nm, producing that narrow

band in the visible spectrum that appears bright

yellow. The perception of any color is therefore due

to the responses generated by three signals varying in

absolute and relative intensity and is known as tri-

chromatic or three-colored vision. Thus, because

cone vision is trichromatic, a suitable mixture of

monochromatic B, G, and R primary lights can

match any colored light. Subsequent processing of

the trichromatic signals by the brain gives rise to

opponent red/green and blue/yellow color perception

mechanisms and an achromatic lightness/darkness

mechanism.

0004The human eye–brain relationship has the ability to

adjust to changes in illumination without much of an

apparent change in the color of the object. This pro-

cess is called adaptation and is accompanied with the

phenomena of color constancy, where colors remain

essentially, but not truly identically, the same hue

when the spectrum of the incident light changes.

Hence, a colored product under a blue white light,

such as occluded daylight with a high component of

blue in the spectrum, will appear to possess a similar

color as the same product under orange–yellow tung-

sten illumination. The reason for this is that, in most

situations, white is normally a component of the

5162 SENSORY EVALUATION/Appearance

scene, and the eye adjusts to recognize white as white,

whatever the light source might be.

Orderly Color Arrangement

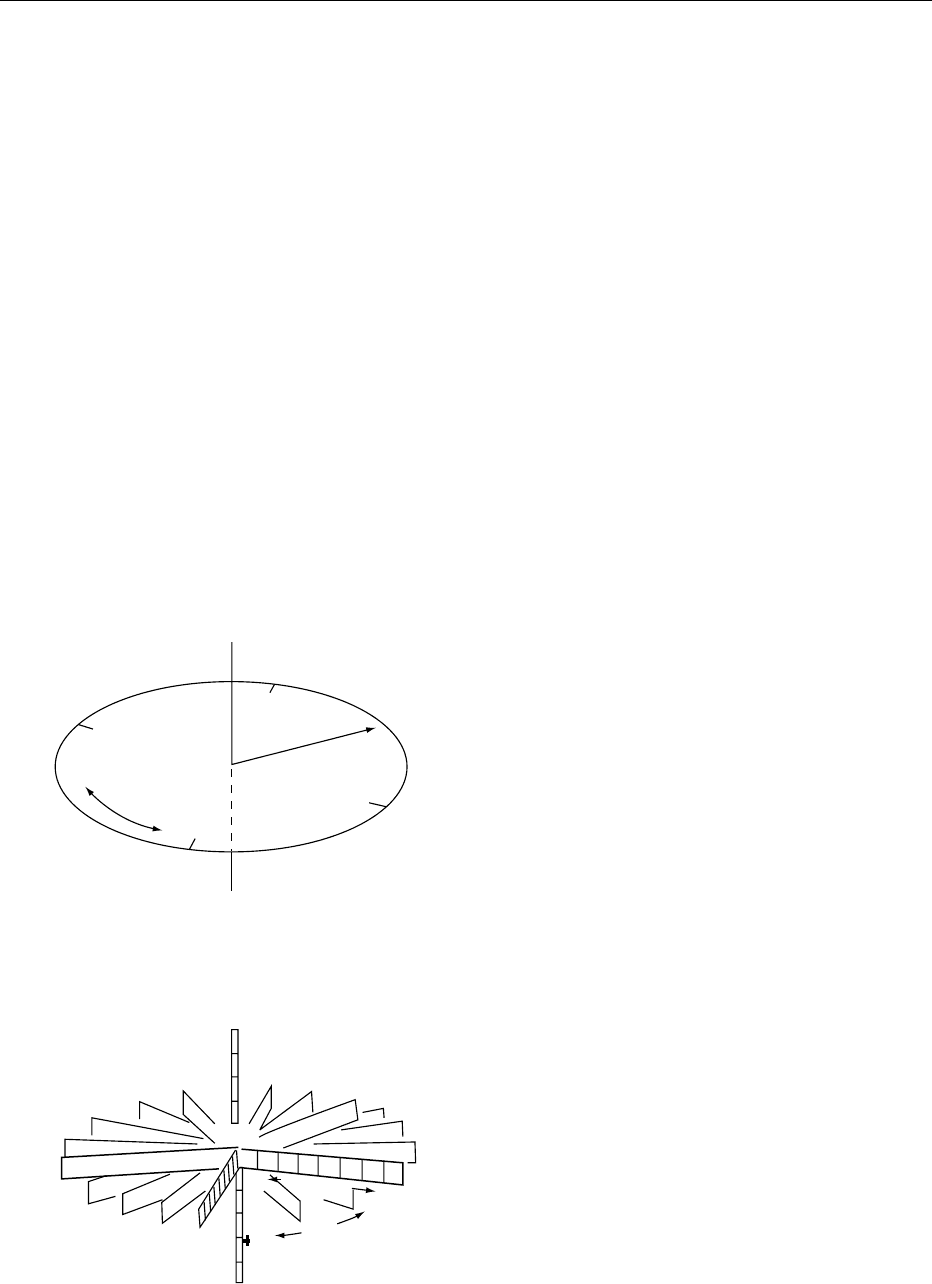

0005 Many attempts have been made to arrange colors in

systematic order (Figure 1). Humans have the ability

to remember between 1000 and 2000 colors, many of

which can be identified by name, and most color

atlases have more than 1000 distinctly different

colors in them. The most obvious arrangement is

that of hue, i.e., the difference between red, orange,

and yellow, etc. to blue following the order of the

colors in the spectrum. This is an insufficient separ-

ation, because colors can also be arranged in order of

their lightness and saturation or intensity. This is the

basis of two of the most commonly used color atlases,

that of Munsell (Figure 2) and the more recent

Natural Color System (NCS). They both have an

achromatic lightness to darkness vertical axis

around which the hues are visually separated and

radiate from the central axis in increasing intensity

(saturation or chroma), but they are conceptually

different. The NCS atlas is based on the fact that

there are four uniquely distinct hue perceptions of

red, yellow, green, and blue although derived from

only the three tristimulus responses. Thus, the hue red

is opposite green, yellow is opposite blue, and the

four resulting quadrants of the space are divided, in

the NCS atlas, into 10 steps. Thus, any color can be

defined by its lightness, hue angle, and chroma values.

The hue arrangement in the Munsell system was

based on visual hue separation. Both atlases enjoy

wide use as reference in the food industry.

CIE Color Spaces

0006Both the above atlases, and others like the Pantone

Color Specifier, are based on visual matching of pig-

ments on paper. For instrumental measurement,

account must be taken of both the nature of the

transmission or reflectance spectrum of the product

and that of the incident light. The ability of an obser-

ver with normal color vision, under strictly controlled

conditions, to match the color of any wavelength with

a mixture of red, green, and blue wavelengths resulted

in the construction of the 1931 CIE (Commission

Internationale de l’Eclairage) color space. Color-

matching functions of the responses to mixtures of

three monochromatic wavelengths in the red, green,

and blue regions were used to match the entire spec-

trum wavelength at a time. This resulted in what is

known as the CIE 1931 2

visual field of view stand-

ard observer and is the basis of all instrumental color-

measurement and color-match prediction. In 1964, a

supplementary set of functions was defined for a wide

field observer of 4

, because, for most practical pur-

poses in real-life situations, samples are viewed at a

wider visual angle than 2

. The functions used in the

calculation of the tristimulus values X, Y, Z have the

advantage that, unlike the original R, G, B matching,

in which some of the matches are negative, they are

all positive with Y equal to the luminance or lightness

of the color. The relationship of X, Y, Z to R, G, B is:

X ¼ 0:49R þ 0:31G þ 0:20B

Y ¼ 0:17697R þ 0:81240G þ 0:0106B

Z ¼ 0:00R þ 0:01G þ 0:99B:

Thus, the values of any set of CIE tristimulus values

X, Y, and Z will define color in three-dimensional

space. Although Y contains the entire lightness or

luminance response, X and Z are more difficult to

relate to color perception directly. The concept of

chromaticity, correlating to the visual recognition of

color perception of hue and color purity can be de-

rived from the coordinates x and y where:

Green

Hue

Blue

Black

Red

Saturation

White

Yellow

Lightness

fig0001 Figure 1 Three-dimensional color order system.

Green

Black

Hue

Yellow

Chroma

Red

Purple

Grey

Blue

Value

White

fig0002 Figure 2 Munsell color system.

SENSORY EVALUATION/Appearance 5163

x ¼ X=ðX þ Y þ ZÞ and y ¼ Y=ðX þ Y þ ZÞ:

Therefore z, which equals (1(x þ y)), is not required

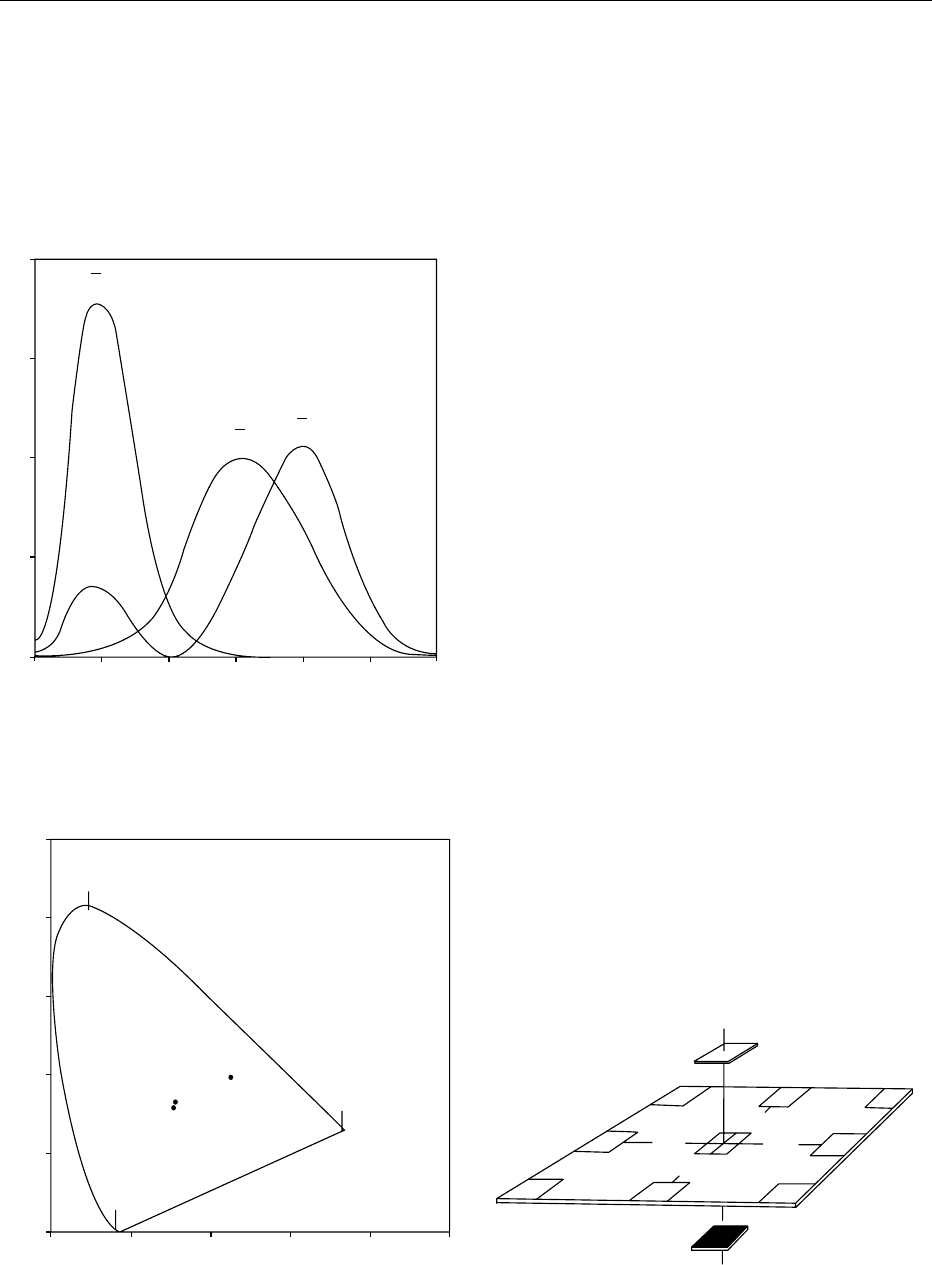

in the construction of the space. The CIE Color

Matching Functions and the 1931 chromaticity dia-

gram are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Uniform Color Spaces

0007Although the development of the 1931 CIE color

space provided a means whereby any color could be

defined unambiguously, it has the major disadvantage

that the colors in the space are not equally separated

from one another visually. For example, the chroma-

ticity distance between just noticeable greens is sev-

eral times greater than the equivalent distance

between just noticeable blues. The objective of any

color-measuring system is not only to provide an

unambiguous definition of color but also to obtain

a realistic relationship to visual perception of color

differences. Two near-uniform color spaces that have

importance to industry are the Hunter and CIELAB

spaces. The Hunter L, a, b opponent color space

(Figure 5) was a development of the earlier Adams

chromatic value systems devised in the mid-1940s,

where red is opposite to green, and yellow is opposite

to blue, i.e., the concept of the four unique hues. The

Hunter L, a, b was constructed in 1958 primarily for

use in color-measuring instruments with analog

devices. The formulae for transformation of the tri-

stimulus values to L, a, b are:

L ¼ 10Y

1=2

a ¼ 17:5ð1:02X YÞ=Y

1=2

b ¼ 7:0ðY 0:847ZÞ=Y

1=2

:

The use of the square root of Y resulted in a color

space that was readily interpretable and approached

visual uniformity when compared with the spacing of

the Munsell color atlas with its uniform and orderly

arrangement of real colors. This space has had wide

application in the food industry but is now being

superseded by the 1976 CIELAB L*, a*, b* color

space, where L*, the cube root of Y, is more uniformly

spaced than L. The formulae are:

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

400 450 500 550 600 650 700

z

y

x

nm

fig0003 Figure 3 CIE color-matching functions for the 2

Standard

Observer.

450 nm

650 nm

520 nm

D

65

C

A

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

y

x

fig0004 Figure 4 CIE x, y chromaticity diagram showing location of

illuminants A, C, and D

65

.

White

Green

Red

Yellow

Blue

Black

L = 100

L = 0

−a

−b

+b

+a

fig0005Figure 5 Hunter three-dimensional uniform L, a, b color

system.

5164 SENSORY EVALUATION/Appearance

L* ¼ 116ðY=Y

n

Þ

1=3

16

a* ¼ 500½ðX=X

n

Þ

1=3

ðY=Y

n

Þ

1=3

b* ¼ 200½ðY=Y

n

Þ

1=3

ðZ=Z

n

Þ

1=3

,

where X

n

, Y

n

, and Z

n

refer to the nominally white

object color stimulus. Although this scale is similarly

constructed to present lightness and opponent colors

with distances that are more nearly inform, it has the

additional advantage of being related to real illumin-

ants rather than the L, a, b space, which used the

theoretical light source C. The three most common

illuminants used in the calculation of L*, a*, b* are

standards A, C and D

65

. A is the spectrum of a

tungsten filament lamp with a color temperature of

2856 K, and C is standard A with a blue filter to

stimulate average daylight with a color temperature

of 6774 K. Illuminant D

65

is the spectrum of the color

of daylight with a correlated color temperature of

6504 K. Currently, the tendency is to use the 10

standard observer and illuminant D

65

rather than

the 2

observer and C. Many modern color spectro-

photometers also have the facility of additional illu-

minants in their programs, e.g., a series of typical

fluorescent lamps of both wide and narrow emission

spectra.

Food Appearance

0008 The most important attribute of any food’s appear-

ance is its color, especially when it is directly associ-

ated with other food-quality attributes, for example

the changes that take place during the ripening of

fruit or the loss in color quality as food spoils or

becomes stale. Every raw food and manufactured

product has an acceptable range of color appearance

that depends on factors associated with the consumer

and the nature of the surroundings at time of judg-

ment and the structure and pigmentation of the food

itself. However, color specification alone is insuffi-

cient to define food appearance. The color quality of

the illumination, in terms of intensity, color tempera-

ture and fidelity and the nature of the structure of the

product all affect the appearance. The distribution of

surface reflectance, the nature of internally scattered

light, and the pigmentation of the product are all

necessary for a complete specification of appearance.

Most important is the interaction of the food’s struc-

ture with its variable light scatter and pigmentation,

which affect opacity and translucency as well as the

color. Small changes in scatter can produce greater

changes in visual color appearance than are attribut-

able to the normal range in pigment concentration in

some products. It is important to distinguish between

these, but this is not always carried out during color

measurement with the consequence that erroneous

interpretation of the data commonly results.

0009A food’s appearance therefore can be reduced to

two principal factors, the physical and the psycho-

logical. The physical factors consist of the geomet-

rical, the food’s dimensions of size, shape and

intrinsic characteristic variability in uniformity and

mass, and the optical, surface gloss or dullness, the

nature and degree of pigmentation, and the light-

scattering power of the food’s structure. The objective,

therefore, is to convert the physical to the psycho-

logical by translating the object’s reflectance or trans-

mittance spectrum into the tristimulus values and

then to a defined color space.

Food Color Measurement

0010As already discussed, foods have an infinite variety of

appearance characteristics. Their surfaces may be dif-

fuse, glossy, irregular, or flat. They may be transpar-

ent, hazy, translucent, or opaque, and their color may

be uniform or patchy. Hence, color-measuring pro-

cedures for foods often have to be modified from the

more standardized techniques used in the measure-

ment of flat opaque surfaces such as paint and paper

for which most color-measuring instruments are

designed. Different instrument optical geometries

will lead to difficulties in sample presentation, produ-

cing different color values for the same material. The

inclusion or exclusion of surface specular reflection in

the measurement depends not only on its importance

as a characteristic of the food but also on the design of

the detector-sensor unit in the instrument. Lateral

transmittance of light through translucent materials

affects their reflectance, and this should be allowed

for in the assessment of such products as tomato paste

and fruit juice, because the ratio of absorption to

scatter varies with aperture area and the concentra-

tion of the components in the product. Colorimeters

and spectrophotometers do not necessarily produce

the same result, because of differences in their con-

struction. Some spectrophotometers give the option

of including or excluding the specular component of

reflectance from the measurement. It has been the

experience of this author to include the component

unless the surface is flat when the difference between

the two readings is likely to be related to the degree of

gloss of the surface. Most colorimeters, unlike spec-

trophotometers which have measuring geometries of

8

/diffuse or diffuse/8

, exclude the specular by meas-

uring at 45

/0

.

0011Measuring at a defined sample thickness is recom-

mended for consistent data. Usually, this would be at

a so-called infinite (?) thickness, where an increase

in thickness would not alter the reading. However, for

SENSORY EVALUATION/Appearance 5165

translucent samples, it is advisable to measure at

more than one thickness on white and black back-

ground to distinguish between the light-scattering

component of reflectance and pigment absorption.

The technique of Kubelka and Munk, used by the

paint and paper industry, is one method. This relates

the ratio of an absorption coefficient (K) over a scat-

ter coefficient (S) to reflectance at an infinite thick-

ness thus:

K=S ¼ð1 R

1

Þ

2

=2R

1

:

It is possible to calculate K and S separately and also

the internal transmittance (T

i

) from the differences in

the readings of the white-backed and black-backed

thin layers.

Measurement Procedures

0012 Because foods are near infinitely variable in their

appearance, it means that there is no consistent way

of measuring them. With few exceptions, e.g., the

measurement of tomato paste, there are no defined

methods, although a variety of approaches have been

found to be successful. For transparent liquids, there

is no difficulty, but care has to be taken to define the

concentration or series of concentrations that are

measured. It can be advantageous to measure a series

of dilutions and relate these to their change in the L*,

a*, b* diagram as well as the normal technique of

absorbance measurement at fixed wavelengths. For

solid materials, reflectance measurements are neces-

sary, and the appearance variables encountered fall

into three classes as follows:

1.

0013 The truly flat and opaque variables are easy to

measure, and the procedure is to measure the

sample at infinite thickness. Infinite thickness is

defined as the thickness that, if it were increased,

would not lead to a change in the data.

2.

0014 The translucent variables are less easy to measure,

because the incident light falling on the material

when viewed by the eye produces an image that is

somewhat different to that presented to the instru-

ment, because the effect of lateral light scatter may

not be left out of the measurement. As well as

measuring at infinite thickness, it is recommended

that the sample be measured as thin sections on

top of black and white from which K, S, and T

i

can

be calculated.

3.

0015 The particulate variables have the difficulty of

holes and gaps in the material, e.g., the surface of

many breakfast cereals is composed of both the

cereal and spaces, which, when judged visually, are

not included in the perception of color but are

included when measured on an instrument. One

way of alleviating the problem is to grind and filter

the sample to a uniform particle size range and

then measure the ground material packed into

a cell.

Visual Assessment

0016Instrumental color measurement is only valid if it

accurately describes the visual characteristics of the

food. The quality of incident light alters the percep-

tion of the food’s color. Light boxes used for color

judgment are now equipped with several light sources

fitted with color-matching lamps and also those typ-

ical of those used in industry. Foods are usually

viewed in the supermarket under ‘warm’ appearing

lighting, because the enhanced red in the spectrum

aids attractiveness. In the home the most likely light

source is the tungsten lamp with its yellow–orange

illumination. However, most color data are re-

ordered relative to D

65

or C, and it should be appre-

ciated that if accurate perceptual equivalence is

required from the measured color data, it should

also be measured to source A or to the requisite

fluorescent lamp.

Realistic Limitations

0017In some industries, particularly the color-matching

industries such as the paint, plastics and printing

industries, the objective of color appearance measure-

ments is to obtain data that are accurately related to

existing colors, e.g., those in an atlas or some internal

standard. This may not be required for specific foods.

Control procedures for quality assurance may only

demand that some critical aspect of appearance be

measured. For some products, a single figure quality

color scale might be appropriate, e.g., one of the CIE

yellowness indexes. In recent years, miniaturization

in instrument manufacture has led to a greater avail-

ability of hand-held colorimeters and spectrophoto-

meters. The use of these instruments, even with their

limitations, in the measurement of the color of food is

likely to increase with commensurate improvements

in assurance of consistent product quality to the

consumer.

See also: Analysis of Food; Browning: Nonenzymatic;

Enzymatic – Biochemical Aspects; Colorants

(Colourants): Properties and Determination of Natural

Pigments; Properties and Determinants of Synthetic

Pigments; Quality Assurance and Quality Control;

Sensory Evaluation: Sensory Characteristics of Human

Foods; Food Acceptability and Sensory Evaluation;

Appearance; Spectroscopy: Visible Spectroscopy and

Colorimetry

5166 SENSORY EVALUATION/Appearance