Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Weighmatic (Figure 2b) two-tank system (Alfa

Laval), which has been specially designed for the

manufacture of recombined icecream and confection-

ery. The whole mixing process is performed with high

accuracy under computer-controlled conditions.

0022 Different systems are used for melting the milk fat.

If the fat is packed in cans, the melting process is

carried out by placing the cans in water at 80

C for

2–3 h. Drums containing AMF are either stored in

rooms at 45–50

C for 24 h or rapidly treated in

steam tunnels or in a hot-water-heated Primodan

butter melter before use. The fat or oil is added into

the mixing tank after complete dissolution of the milk

powder has been achieved. Depending on the equip-

ment, the melted fat is either pumped or discontinu-

ously added into the mixing vessel.

Filtration, Homogenization, and Pasteurization

0023 From the mixing tank, the product is transferred via a

balance tank to a separation unit, consisting of either

duplex filters, made from stainless steel with nylon

nets, or a clarifier, in order to remove extraneous

matter and undissolved particles. Most recombined

milk products are homogenized. Depending on the

product type, different conditions of homogenization

are employed. For most of the products, two-stage

homogenization should be preferred. Typical pres-

sures are 14 MPa plus 3.5 MPa for whole milk,

17 MPa plus 3.5 MPa for evaporated milk. (See Fil-

tration of Liquids.)

0024 Pasteurization is carried out mainly following the

conventional dairy technology, using continuous heat

exchangers rather than batch heating. The latter

system is used only in small-scale production units.

Typical conditions are 73

C for 15 s for whole milk,

75–80

C for 20–30 s for evaporated milk, 86–92

C

for 30 s for sweetened condensed milk. (See Pasteur-

ization: Principles.)

0025 Normally, the recombined milk flows from the

production line to the filling station, thereby passing

buffer tanks. They should be of the aseptic type in the

case of sterilized or UHT milk. (See Heat Treatment:

Ultra-high Temperature (UHT) Treatments; Steriliza-

tion of Foods.)

Future Perspectives

0026 Scientific progress has contributed considerably

to the development of improved technologies for

recombination of dairy products as well as to the

successful use of special dairy-based ingredients.

Examples such as the manufacture of recombined

feta-type and other cheeses, using retentate or high-

protein powders from ultrafiltration technology, con-

firm this trend. In this context, the functional proper-

ties of various components should be well recognized,

since they can be utilized specifically. Furthermore, in

many of the countries with a recombination industry,

long-life milk products would allow a more conveni-

ent distribution and storage. Following this aim,

modern processes such as UHT technology,

cleaning-in-place cleaning facilities and aseptic pack-

aging lines must be considered as factors of growing

importance. (See Cheeses: White Brined Varieties.)

See also: Antioxidants: Natural Antioxidants; Butter: The

Product and its Manufacture; Casein and Caseinates:

Uses in the Food Industry; Cheeses: White Brined

Varieties; Emulsifiers: Uses in Processed Foods;

Filtration of Liquids; Flavor (Flavour) Compounds:

Production Methods; Heat Treatment: Ultra-high

Temperature (UHT) Treatments; Pasteurization:

Principles; Stabilizers: Types and Function; Sterilization

of Foods; Vegetable Oils: Types and Properties;

Vitamins: Overview; Whey and Whey Powders:

Production and Uses; Protein Concentrates and Fractions

Further Reading

Al-Tahiri R (1987) Recombined and reconstituted milk

products. New Zealand Journal of Dairy Science and

Technology 22: 1–23.

International Dairy Federation (1982) Milk for the Mil-

lions. Proceedings of the IDF Seminar on Recombin-

ation of Milk and Milk Products, Singapore 1980.

Bulletin No. 142.

International Dairy Federation (1990) Recombination of

Milk and Milk Products. Proceedings of the Inter-

national Seminar, Alexandria, Egypt, 1988. Special

Issue No. 9001.

Kjaergaard Jensen G and Nielsen P (1982) Reviews of the

progress of dairy science: milk powder and recombin-

ation of milk and milk products. Journal of Dairy

Research 49: 515–544.

Mann EJ (1988) Recombined and reconstituted milk. Dairy

Industries International 53: 15–16.

Pedersen PJ (1985) Plants for recombination. In: Hansen R

(ed.) Evaporation, Membrane Filtration and Spray

Drying in Milk Powder and Cheese Production,

pp. 373–383. Vanlose, Denmark: North European

Dairy Journal.

4926 RECOMBINED AND FILLED MILKS

Recommended Dietary Allowances See Dietary Reference Values

Refining See Sugar: Sugarcane; Sugarbeet; Palms and Maples; Refining of Sugarbeet and Sugarcane;

Spices and Flavoring (Flavouring) Crops: Tubers and Roots; Properties and Analysis; Spoilage: Chemical and

Enzymatic Spoilage; Bacterial Spoilage; Fungi in Food – An Overview; Soy (Soya) Beans: The Crop; Processing

for the Food Industry; Properties and Analysis; Dietary Importance

Refrigeration See Chilled Storage: Principles; Attainment of Chilled Conditions; Quality and Economic

Considerations; Microbiological Considerations; Use of Modified-atmosphere Packaging; Packaging Under

Vacuum

REFUGEES

A M Madden, London Metropolitan University,

London, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 A refugee is a person who, ‘owing to a well-founded

fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion,

nationality, membership of a particular social group,

or political opinion, is outside the country of his

nationality, and is unable . . . to avail himself of the

protection of that country,’ as defined by the United

Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). It

is estimated that there are approximately 12.1 million

people in the world today who have legal status as

refugees and that a further 1.2 million people, de-

scribed as asylum seekers, are in the process of apply-

ing for refugee status. It is also estimated that another

25–30 million people have fled their homes for the

same reasons as refugees, but as they have not left

their country of origin, they are classed instead as

displaced people. These groups are distinguished

from economic migrants who retain, at least theoret-

ically, the protection of their country of origin. The

problems relating to food and nutrition for refugees,

asylum seekers, and displaced people are similar and,

in many situations, indistinguishable. For simplicity

in this article, the term ‘refugee’ will be used to in-

clude all asylum seekers and displaced people except

where there is a significant legal difference which

pertains to their ability to purchase food or obtain

employment.

0002Since data were first collected in 1951, the total

number of individuals categorized as refugees has

increased substantially overall and in most regions

of the world (Table 1). War and its consequences

have led to the movement of the greatest numbers of

refugees during this period, as typified in Europe after

the Second World War, in South-east Asia following

the prolonged and geographically widespread effects

of the Vietnam war, and in India where 10 million

people fled to India in 1971 following the Bangla-

deshi war of independence. In many situations, the

effects of war have been exacerbated by famine,

tbl0001Table 1 Estimated number of refugees by region (in

thousands)

1951 1970 19 80 19 9 0 2 0 0 0

Africa 5 998 4154 5891 3611

Asia 42 159 2728 7944 5375

Europe 1221 646 574 1468 2427

Latin America and Caribbean 120 110 179 1197 38

North America 519 519 942 618 629

Oceania 180 44 315 110 68

Total

a

2116 2480 8894 17 229 12 148

a

Including some uncharacterized by region.

Source: governmental data compiled by United Nations High Commission

for Refugees (2000 and 2001). United Nations High Commissioner for

Refugees, UNHCR (2000) The State of the World’s Refugees. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

REFUGEES 4927

either directly or in combination with drought, as in

the Horn of Africa during the 1980s.

0003 In addition to large movements of populations

whose motivation is primarily survival, some people

become refugees as individuals and for personal

reasons. These may include political persecution, con-

scientious objection to war or military service, or fear

of attack for refusing to comply with cultural expect-

ations, for example, wearing restrictive clothing or

undergoing genital mutilation. Inevitably, the nutri-

tional implications of refugee-hood for such individ-

uals are very different from those affecting refugees

displaced in large numbers as a consequence of armed

conflict.

0004 The food and nutritional issues affecting refugees

vary considerably depending on their geographical

homeland and area of relocation, the health and nu-

tritional status of individuals before displacement, the

duration of displacement, external factors such as

conflict and loss of infrastructure, and the availability

of humanitarian relief. In addition, psychosocial and

cultural influences may also have a major effect on the

nutritional well-being and food needs of these people

which in total represent almost 1% of the world’s

population. Against this background, the food and

nutrition of refugees can be considered in two separate

contexts: first, the emergency provision of food in

refugee camps and, second, the nutritional well-

being of refugees after moving to countries of asylum.

The Emergency Provision of Food in

Refugee Camps

0005 Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights (1948) states that ‘Everyone has the right to a

standard of living adequate for health . . . including

food ....’ While recognizing the indispensable need

for food, it is impossible to consider the nutritional

requirements of refugees in isolation without ac-

knowledging the essentiality of a place of physical

safety and access to clean water, sanitation, and

health care facilities. These factors, along with nutri-

tion and food aid, represent the five pillars which

support the Humanitarian Charter, an interagency

collaboration aiming to increase the effectiveness of

humanitarian assistance to people affected by disas-

ters. Each pillar of the Charter is in turn supported by

a set of universal minimum standards. The standards

for nutrition focus on general nutrition support to the

population and nutrition support to those suffering

from malnutrition; the standards for food aid con-

sider the food rations required, targeting of food,

resource management, logistical operations including

transport and storage, and food distribution to the

people in need.

Food Rations for Refugees

0006Food rations for refugees generally comprise a staple

cereal, vegetable oil, and sometimes pulses and salt.

Some rations are deficient in overall energy content

and provide inadequate micronutrients. As a result,

refugees may suffer from diseases of nutrient defi-

ciency, including protein energy malnutrition, beri-

beri, pellagra, and scurvy. In 1997, the average

nutritional requirements for refugee food rations

were increased by the World Food Programme and

UNHCR to 2100 kcal (8782 kJ) per person per day, in

line with World Health Organization recommenda-

tions (Table 2). These figures are based on a defined

demographic profile which, if different from the

population under consideration, will necessitate ad-

justment to the average requirements.

0007In order to prevent or correct micronutrient defi-

ciencies, the World Food Programme and UNHCR

recommend that at least some of the food rations

should be provided in the form of blended foods,

particularly for refugees who are totally dependent

on food aid. Blended foods are a precooked mixture

of cereal and oil seed and sometimes a pulse such as

chickpeas to which a vitamin and mineral mixture has

been added. Generally, they are expensive as most are

produced in the USA, although the World Food Pro-

gramme has also procured some produced locally to

requirements.

0008Powdered or modified milk should not be included

in general food distribution to refugees because of the

potential hazards associated with inappropriate dilu-

tion, contamination and, in some populations, lactose

intolerance. Support for breast-feeding is paramount

as facilities for safely preparing formulae are rarely

available in refugee camps; in situations where sani-

tation is inadequate, the death from diarrheal disease

tbl0002Table 2 Average nutritional requirements used for initial

planning purposes in refugee camps, based on a defined

demographic pattern

Nutrient Mean population requirement

Energy 2100 kcal (8782 kJ)

Protein 10–12% total energy (52–63 g) but <15%

Fat 17% total energy (40 g)

Vitamin A 0.5 mg retinol equivalents

Thiamin 0.9 mg (or 0.4 mg per 1000 kcal intake)

Riboflavin 1.4 mg (or 0.6 mg per 1000 kcal intake)

Niacin 12.0 mg (or 6.6 mg per 1000 kcal intake)

Vitamin C 28.0 mg

Vitamin D 3.2–3.8 mg calciferol

Iron 22 mg (low bioavailability, i.e., 5–9%)

Iodine 150 mg

Source: The Sphere Project (2000) Humanitarian Charter and Minimum

Standards in Disaster Response. Oxford: Oxfam Publishing, with

permission.

4928 REFUGEES

is 14 times higher in artificially fed babies than in

those who are breast-fed.

Suitability of Food Aid

0009 Although in extreme starvation people might con-

sider eating any potential food, it is well recognized

that the acceptability of foodstuffs provided for refu-

gees in humanitarian relief operations must be con-

sidered in order to optimize any nutritional benefit.

Unpopular, unpalatable, or difficult-to-prepare foods

may be exchanged for preferred items as observed,

for example, in camps in Kenya, Guinea, and Zaire,

where refugees sold maize at a financial loss in order

to buy rice and nonfood requisites. Although the

resulting diets had an improved micronutrient con-

tent, the total energy content fell, further jeopardizing

nutritional well-being. Generally, blended cereal

foods are well accepted, particularly by people who

are already familiar with porridge-type foods. In Ethi-

opian refugee camps, where only a limited variety

of food items were available for approximately 6

months, sensory-specific satiety or ration fatigue has

been observed. It has been suggested that the provi-

sion of sugar, chilli, and other spices may alleviate

poor appetites induced by repeatedly eating the

same foods; although flavorings and condiments

contribute little nutritional value of their own, they

may help refugees eat sufficient to maintain an ad-

equate intake.

Nutritional Well-Being After Moving to

Countries of Asylum

0010 While considerable attention has been given to the

nutritional needs of individuals living temporarily in

refugee camps, relatively less regard has been paid to

the nutritional well-being of refugees once they have

settled in a host country which is often geographically

and culturally distant from their homeland. Govern-

mental data indicate that approximately 418 000

people applied for refugee status in European coun-

tries during a 12-month period to March 2001, with

approximately 18% of applications being received in

the UK (Table 3).

0011 The provision of housing, legal assistance, and

basic health care is usually amongst the first priorities

dealt with by organizations assisting newly arrived

refugees and asylum seekers, with education and psy-

chological support, primarily for the young, also re-

ceiving attention. Few systematic studies have been

undertaken to evaluate the nutritional status of refu-

gees living in western countries, although there are a

number of factors which suggest that they may be at

nutritional risk (Table 4).

Nutritional Status on Arrival

0012The nutritional status of some individuals may be

suboptimum when they arrive in the host country

and this will be influenced by their general health,

the nature of their departure from their homeland, the

journey undertaken in flight, and any intervening

periods spent in camps en route. Refugees from

some countries, for example, Ethiopia, Somalia, and

Sudan, may have been exposed to communicable and

parasitic diseases, including tuberculosis, malaria,

and schistosomiasis, which may further impair an

already diminished nutritional status. Individuals

arriving from European countries are less likely to

suffer from obvious nutritional depletion, generally

because of their better initial nutritional status, shorter

periods of displacement, and prior vaccination to

common communicable diseases, although inevitably

there are exceptions. Some refugees who have en-

dured long overland journeys, often covertly crossing

several international borders, may arrive depleted

and at risk of weight loss and subclinical micronu-

trient deficiency after consuming an inadequate diet

for several weeks or longer.

0013At present, many templates for the health screening

of newly arrived refugees in the UK do not make

reference to nutritional variables. This is a cause for

concern, particularly for infants and children who are

most likely to be at nutritional risk and for whom the

consequences of nutritional depletion are greatest.

Evaluation of their nutritional status on arrival is,

therefore, imperative.

tbl0003Table 3 Asylum applications lodged in Europe (2000–2001)

Country ofasylum Numberofapplications Share (%) Ranking

Germany 80 879 19.4 1

UK

a

75 290 18.0 2

Netherlands 41 944 10.0 3

Belgium 41 642 10.0 4

France 39 043 9.3 5

Austria 21 995 5.3 6

Total 417 743 100

a

UK data are number of cases (average of 1.3 individuals per case).

Source: Governmental data (1 April 2000–31 March 2001) compiled by

United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

tbl0004Table 4 Factors influencing the nutritional status of refugees

after resettlement

Nutritional status on arrival

Poverty

Cultural factors

Communication

Psychological issues

REFUGEES 4929

0014 Not all newly arrived refugees have nutritional

problems, however, and many are generally in good

health and physically fit. There is evidence that the

health status of some refugees deteriorates and is

worse 2–3 years after arrival in the host country. In

some cases the cause for this deterioration may relate

specifically to their situation as refugees, for example

with tuberculosis and mental health problems, while

in others, it may be a consequence of adopting an

unhealthy urban lifestyle and diet. Obesity has been

observed in Chilean and Bosnian refugees in Sweden,

even after adjustment for socioeconomic status, and

there is a high incidence of dental caries in young

Vietnamese refugees which increases with the length

of stay in the host country.

Poverty

0015 After arriving in a host country, many refugees live in

poor housing, receive limited financial support, and

have difficulty obtaining paid work. As a conse-

quence, their ability to purchase food and eat a

healthy diet is constrained. Policies of dispersal in

the UK have resulted in many refugees being housed

in areas away from their initial point of entry, but

typically, refugees settle in the poorest areas of large

cities. Many of these deprived urban areas, where

few supermarkets are located, are considered ‘food

deserts’ and, in the absence of adequate cheap trans-

port, the local residents have little choice but to buy

their food from small corner shops. Generally, these

sell a limited range of food products and few fresh

fruit and vegetables, for which they charge relatively

high prices. Asylum seekers are initially housed in

temporary accommodation until their refugee status

is legally confirmed, which may take several months

or longer. Such accommodation is usually found in

bed-and-breakfast establishments or small hotels

where there are few cooking facilities and limited

storage for food. Inevitably, it is difficult for people

living in these situations with limited money to eat a

healthy diet.

0016The financial support provided for refugees varies

between host countries, the legal status of the appli-

cant and, in some cases, where the application for

refugee status is made. In most countries, no benefit

is paid to people applying for asylum until they are

granted legal refugee status unless they can demon-

strate financial hardship and then they may receive

reduced levels of benefit (Table 5). For example,

asylum seekers in Germany receive their accommoda-

tion, a food parcel, some clothing, and a small sum of

money for ‘personal requirements’ each month. Fi-

nancial benefit is only paid in exceptional circum-

stances and then, for the first 12 months, at a rate

20% lower than that given to other members of the

community. Similarly, in the UK, asylum seekers are

supported through a virtually cashless system, receiv-

ing vouchers to a value of 30% less than income

support paid to other recipients. Vouchers can be

exchanged for food and basic necessities only at des-

ignated shops but cannot be traded for money. This

has caused some difficulty for refugees wishing to

purchase halal meat from specific outlets. The intro-

duction of food vouchers is unpopular and has been

widely criticized by a number of refugee and nutrition

organizations as inflexible and potentially comprom-

ising nutritional intake. Applications for asylum may

take several months or longer to be processed, during

which a single adult aged over 25 years would receive

£36.54 per week in vouchers. The quantity and qual-

ity of food that can be purchased for this figure is

limited, particularly if access to cheaper shops and

cooking facilities are not available. If individuals are

granted legal refugee status they are entitled to cash

benefits at the usual value of income support to

other UK claimants and may also be entitled to

a back-dated cash sum. On being granted legal

status, refugees are entitled to move from temporary

tbl0005 Table 5 Eligibility of asylum seekers for benefits and employment

Country of asylum Financial and other benefits Employment eligibility

Australia Financial hardship only: 89% of standard benefits Dependent on visa (if any)

Belgium Theoretically eligible but local authority-dependent Provisional work permit if claim deemed

admissible

Canada Welfare assistance available if meet financial criteria Eligible to seek work after submitting appropriate

form

France Financial help as a cash sum. Eligible for social security No access to labor market unless authorized

Netherlands Free board and lodging plus small monthly cash sum Not eligible

Sweden Eligible for social benefit, paid daily if necessary No work permit required if decision expected

<4 months

Switzerland Eligible for welfare benefits at reduced rates paid ‘in kind’ Not eligible for first 3 months

USA Information not available Not eligible

Adapted from Bloch A and Levy C (1999) Refugees, Citizenship and Social Policy in Europe. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

4930 REFUGEES

accommodation to a more permanent residence

where the cash sum could be used to purchase kitchen

and other essential household items which might help

facilitate an improved food intake.

0017 The term ‘refugee’ embraces people from a multi-

tude of backgrounds and includes people with a wide

variety of employment skills. Although varying

greatly with area of origin and gender, a high propor-

tion of refugees are well-educated and professionally

trained. However, obtaining work is forbidden in

most host countries until legal refugee status is estab-

lished, and even then, is often very difficult, even for

professionals whose qualifications may not be recog-

nized (Table 5). As a result, there is a high level of

unemployment in most refugee communities and, of

those who are working, many are employed in low-

paid, unskilled, and sporadic jobs. Whilst not influ-

encing food intake directly, the difficulty in obtaining

work and consequent relative poverty exacerbates

the problems already outlined and makes it difficult

for individuals to work their way out of financial

hardship.

Cultural Factors

0018 Refugees are not a homogenous group which can be

considered together, coming as they do from many

different countries from all geographical regions of

the world and bringing with them a wealth of culture

and tradition which may differ considerably from

those of their host country (Table 6).

0019 In addition to providing dietary energy and essen-

tial nutrients, food plays important social and cul-

tural roles for most people. The foods eaten, the

methods of preparation and serving, and the context

in which they are consumed often have significant

social meaning and help define group identity. For

refugees displaced from their homeland and often

separated from their families and friends, the

importance of food symbolism may grow and in

some cases may represent one aspect of their lives

over which they have some control. However, diffi-

culties arise when familiar food items are unavailable

or can only be purchased at great expense or from

specialist shops in areas where there is a refugee com-

munity of significant numbers. Similarly, familiar

cooking implements or facilities may not be available

and preclude the preparation of specific dishes.

Whilst most refugees quickly become skilled at

adapting available substitutes and learning new skills,

food intake will by necessity change and may lead to a

diet which is nutritionally inadequate compared to

their traditional fare.

0020Food habits may also need to be adapted in terms

of who prepares the meals and with whom food is

shared. Refugees who traditionally live in extended

families where women frequently undertake most of

the food preparation and do not have outside employ-

ment may find themselves living in smaller and more

isolated nuclear family groups where a large shared

meal is no longer a major focus of the day. Many

refugees are young men who may have had little

practical experience of preparing their own food. A

study of single male Ethiopian refugees living in

Ottawa, Canada, found that their total energy intake

was related to their domestic skills and that a lack of

such skills was the most commonly perceived dietary

problem.

0021Children who may have been expected to contrib-

ute to food preparation and cooking in their home-

land may be influenced by their host country peers,

who generally have less responsibilities, and as a

result wish to avoid participation in household tasks

which might be viewed by others as exploitation. In

Minneapolis, USA, 30–45% of adolescent refugees

from South-east Asia report primary responsibility

for preparing the evening meal. A Kurdish mother in

London described how ‘at home, an eight-year-old

could cook a meal. Now they can’t do anything.

They just watch television all day’. Some children

may select a more western-type diet in order to try

to fit in with their contemporaries or to distance

themselves from painful memories of their homeland

while others may cling to traditional habits and avoid

the stress of trying unfamiliar foods.

Communication

0022Some, but not all, refugees arrive in the host country

speaking the local language. For those who do not, an

inability to communicate easily may increase difficul-

ties experienced in many aspects of life, including

shopping for food. This becomes an increasing prob-

lem when the available foods are unfamiliar and

ingredients or cooking instructions cannot be read.

tbl0006 Table 6 Origin of asylum applicants in Europe (2000–2001)

Nationality Number of

applications

Share

(%)

Ranking

Iraq 37 902 9.1 1

Yugoslavia, Former Republic of 37 174 8.9 2

Afghanistan 32 992 7.9 3

Iran, Islamic Republic of 27 853 6.7 4

Turkey 24 647 5.9 5

Russian Federation 15 489 3.7 6

Bosnia and Herzegovina 13 468 3.2 7

Sri Lanka 11 986 2.9 8

India 9516 2.3 9

Sierra Leone 8321 2.0 10

Total 417 743 100

Source: Governmental data (1 April 2000–31 March 2001) compiled by

United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

REFUGEES 4931

For refugees who may be familiar with growing much

of their own food or shopping in a market, food

shopping can present some difficulty. Generally,

school-aged children and men are more likely than

women to speak the host country language and yet

women are often charged with shopping for food.

Whilst interpreters may sometimes be available, they

generally assist with legal issues or essential health

matters and are rarely used for what may be con-

sidered more mundane food-related communication.

However, health authority interpreters in the UK pro-

vide a free service for hospitals and general practice

surgeries and should be available for nutritional con-

sultations if required.

Psychological Issues

0023 Refugees may have faced many diverse experiences

before arriving in their host country. Some have

suffered violence, loss, separation, family disruption,

and terrifying journeys. Concerns may continue even

when a place of perceived safety is reached, including

uncertainty over asylum, anxiety for relatives left

behind, difficult living conditions, hostility from local

people, and the challenges of settling into a new life.

As a consequence, many refugees report psycho-

logical problems, with two-thirds of adult refugees

in the UK experiencing anxiety or depression and

90% of Bosnian children in the USA showing signs

of posttraumatic stress disorder. Other symptoms,

which may be exacerbated by poverty and isolation,

include poor sleep patterns, loss of memory, panic

attacks, and agoraphobia. Loss of appetite and lack

of interest in food may also be a problem.

0024 Approaches to psychological well-being vary be-

tween cultures. Refugees from some backgrounds

may be uncomfortable with western-style counseling

or ‘talking treatments’ and prefer instead to attend to

practical issues which they consider will make their

lives better. Interestingly, food and nutrition are per-

ceived by many as ‘safe’ subjects and have been used

as a focus for discussion groups in both Canada and

the UK as a way of providing practical and emotional

support for refugee women in a nonthreatening en-

vironment. The cooking of traditional recipes and

sharing of food has also been used as therapy in a

group of London-based refugees recovering from

torture.

See also: Eating Habits; Ethnic Foods; Famine,

Starvation, and Fasting; Infants: Breast- and Bottle-

feeding; Nutritional Assessment: Importance of

Measuring Nutritional Status; Anthropometry and Clinical

Examination; Politics and Nutrition; World Health

Organization

Further Reading

Aldous J, Bardsley M, Daniell R et al. (1999) Refugee

Health in London. London: The Health of Londoners

Project.

Bloch A and Levy C (1999) Refugees, Citizenship and

Social Policy in Europe. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

Burnett A and Peel M (2001) Health needs of asylum

seekers and refugees. British Medical Journal 322:

544–547.

Hilderbrand K, Boelaert M, Van Damme W and Van der

Stuyft P (1998) Food rations for refugees. Lancet 351:

1213–1214.

Mears C and Young H (1998) Acceptability and Use of

Cereal-Based Foods in Refugee Camps. Oxford:

Oxfam GB.

Richman N (1998) In the Midst of the Whirlwind. A

Manual for Helping Refugee Children. Stoke on Trent:

Trentham Books.

Sellen DW and Tedstone A (2000) Nutritional needs of

refugee children in the UK. Journal of the Royal Society

of Medicine 93: 360–364.

The Sphere Project (2000) Humanitarian Charter and Min-

imum Standards in Disaster Response. Oxford: Oxfam

Publishing.

Trafford P and Winkler F (2000) Refugees and Primary

Care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR

(2000) The State of the World’s Refugees. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Wallace R and Brown A (1999) Asylum Practice and Pro-

cedure. London: Trenton Publishing.

Regulations See Legislation: History; International Standards; Additives; Contaminants and Adulterants;

Codex

4932 REFUGEES

RELIGIOUS CUSTOMS AND NUTRITION

P Christian, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD,

USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Religious Dietary Laws and Nutritional

Status

0001 Food in all human societies is more than just a source

of nutrition required for survival. It is deeply en-

trenched in the religious, social, and economic aspects

of life and carries with it various symbolic meanings,

many of which express the relationship between

humans and their deities. Among numerous factors

that shape dietary practices, religious laws are most

prevailing. Religious dietary regulations which deter-

mine food-related behaviors of individuals are codi-

fied in the written religious texts and holy scriptures,

although different interpretations of these may also be

found. The extent to which individuals follow food-

related prescriptions or proscriptions may depend on

their religiosity – the degree to which they adhere to a

set of religious beliefs. Some dietary habits may not

have their origins in religious doctrines, but are ad-

hered to due to a strongly held cultural or traditional

belief common to the members of a religious group

and may be tied to a religious or historical event.

0002 The origins of religious dietary laws have been

extensively debated by both ancient and modern-

day scholars, although no single theory appears to

be well-accepted. Among theories that exist, the ones

that are related to dietary laws being divine com-

mandment, or having allegorical parallels or esthetic

origins are considered subjective and emotional in

nature. Other theories, based on reasons of health

and sanitation, ethnic identity, and ecology, are gen-

erally more well-accepted. For example, reasons of

health and sanitation are considered the best scientific

explanations for the prohibition of carrion, pork, and

blood in Judaism and Islam. Supporters of this theory

contend that the cause–effect relationship between

ingestion of specific foods and the manifestation of

disease are reflected in the dietary laws prescribed in

the scriptures. On the other hand, the ecologic theory

propounds that because the environment is more fa-

vorable towards the availability of certain types of

flesh foods but not others, proscriptions regarding

eating the latter type of animal foods makes economic

sense. The hypothesis pertaining to ethnic identity

suggests that dietary laws and codes set aside one

religious/ethnic group from another and tend to foster

religious and ethnic cohesiveness.

0003Noteworthy are the shared attributes of the dietary

regulations across different religions. All major reli-

gions have prohibitions, either permanent or tem-

porary, regarding consumption of animal foods. In

Hinduism and Buddhism, killing living creatures is

abhorred and meat consumption is forbidden. Juda-

ism and Islam forbid the consumption of pork, and

meat intake is restricted on fasting days among ortho-

dox Christians, and on Fridays among Catholics.

Most religions also advocate religious fasting, usually

associated with religious observances. Fasting is con-

sidered to be an act of penitence and is practiced in

order to gain spiritual merit. Most religious fasts last

over a brief period of time with either total abstinence

from food or from specific food items. The Ramadan

fast, observed every year by Muslims, worldwide, is

the most studied of all religious fasting customs. The

Eastern Orthodox Church observes two major fasts:

the Lent fast and the Advent fast in the 40 days

preceding Easter and Christmas, respectively.

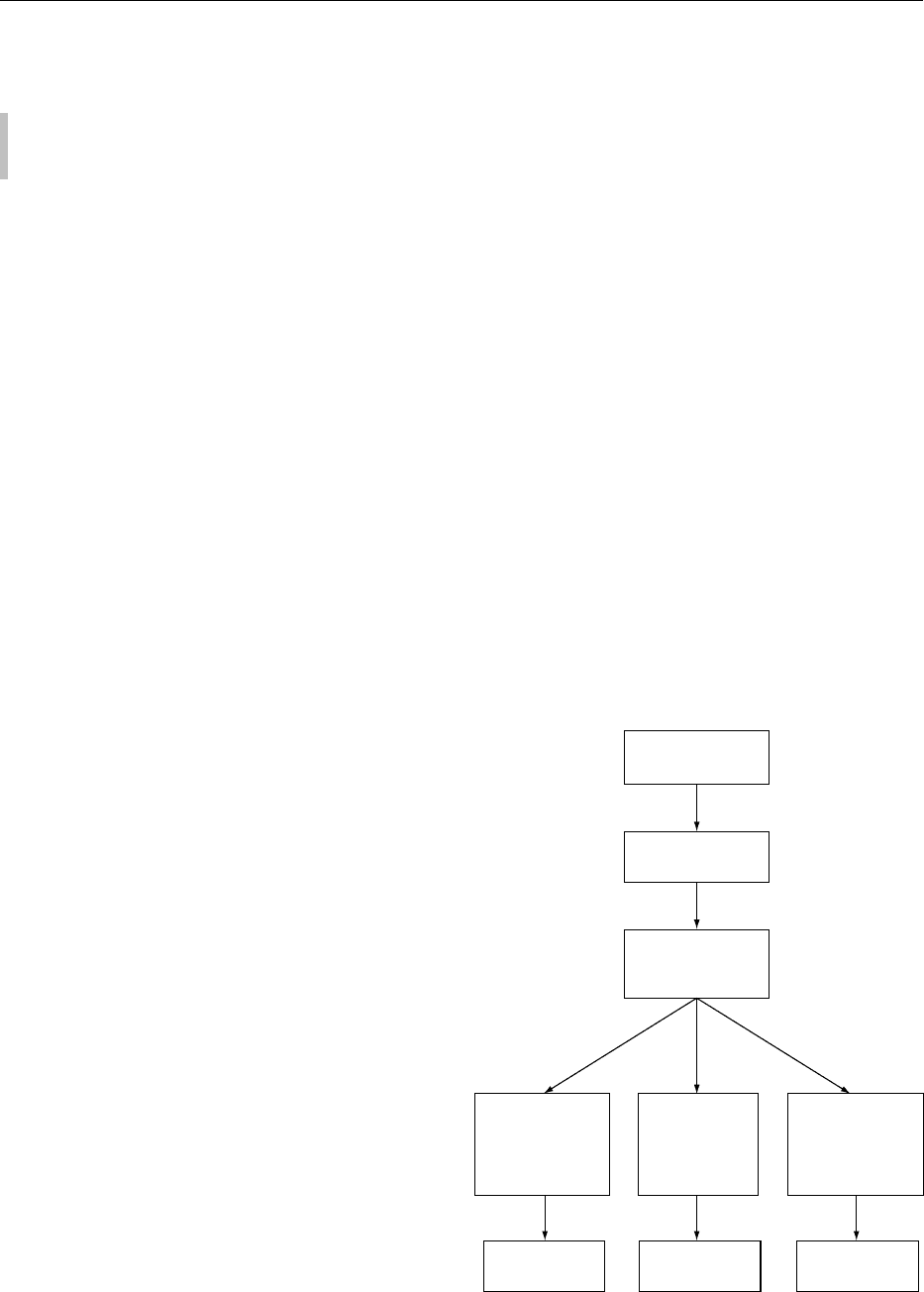

0004Religious dietary prescriptions or proscriptions as

outlined by dietary laws and guidelines can be

broadly classified into ceremonial, periodic, or habit-

ual (Figure 1). Ceremonial prescriptions, such as

Religious beliefs/

doctrines

Food laws and

guidelines

Dietary

prescriptions and

proscriptions

Ceremonial Periodic

(fasts, e.g., Ramadan,

Lent, or Advent)

Habitual

(prohibition of specific

foods, e.g., animal flesh

in Hinduism)

(foods consumed to

commemorate

religious events, e.g., at

Easter or Passover)

Little or no

effect

Potential short-

term effect

Chronic long-

term effect

fig0001Figure 1 Religious dietary laws and types of nutritional effects.

RELIGIOUS CUSTOMS AND NUTRITION 4933

eating lentil soup on Good Friday, symbolizing the

tears of the Virgin Mary, or lamb on Easter, or

‘seder’ plate with foods symbolic of events in Jewish

history at Passover, may have little or no nutritional

effects and are not considered here. Periodic customs

such as religious fasting may result in a potential

short-term alteration in a group’s nutritional status.

Dietary guidelines that prohibit all animal foods, such

as in Hinduism and Buddhism, are habitual and likely

to have chronic long-term effects on nutritional status

and health. Prohibition of pork in Judaism or Islam

falls in this category of dietary proscriptions but its

nutritional effects are unknown. Data are scant on the

relationship between religious customs and nutri-

tional status. Also, certain food practices may be

latent in modern times, with little known about their

nutritional effects. None the less, particular groups

of individuals, following clearly defined and unique

dietary customs of their religion, have been studied,

to some extent, in order to understand better the

nature of such customs in relation to their nutritional

and health outcomes. These cover religious dietary

customs of each of the five major religions of the

world – Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and

Buddhism – and are described below in more detail.

The Fast of Ramadan

0005 One of the most common religious practices uni-

formly followed by Muslims throughout the world

is that of fasting in the month of Ramadan. Fasting in

Ramadan is one of the Five Pillars of Islam, the others

being the statement of faith, prayers five times a

day, giving your dues to the poor, and pilgrimage to

Mecca. The holy scriptures of Qur’an reveal the

reasons for fasting: the main one is the Revelation of

Qur’an, a guidance for mankind and the criterion of

right and wrong, which occurred in this month

(2.185). Fasting is also considered a training in self-

control, of restraining one’s needs and desires, and

in deepening spiritual life. According to Prophet

Mohammed, fasting can also improve health, and

Muslims fast for better health.

0006 Fasting during Ramadan is partial or controlled, as

Muslims abstain from food and drinks during the

hours from sunrise to sundown. Fasting is obligatory

for every adult Muslim, although sick individuals or

those traveling, and pregnant and lactating women

are exempt but have to make up for the missed days.

Elderly people and children under the age of puberty

are also exempt, although the former group is

expected to give food, cash, or kind to a needy person

for each day of missed fast. Fasting is forbidden for

women during menstruation but they are also re-

quired to make up for the missed days.

0007On the night before fasting commences and each

night thereafter, Muslims consume a predawn meal

called ‘sahoor’, after which they abstain from eating

or drinking until sundown. Immediately after sunset

the fast is broken with a meal called ‘iftar’. There are

primarily three types of changes that occur in the

food-related behaviors of Muslims during this

month. One is the change in the frequency and time

of meal consumption, with long periods of fasting

and short periods of food intake which might result

in gorging. Frequency of eating decreases from an

average of 4.4 times to 2.8 times per day during

Ramadan. The second change that occurs is in the

types of foods consumed during Ramadan. It is cus-

tomary to prepare and consume special foods which

are rich in protein and carbohydrates as well as eat

fresh or dried fruits and vegetables. The third notable

change is in the sleeping pattern, since the number of

hours of sleep is reduced due to the predawn partak-

ing of breakfast.

Fasting During Ramadan and Nutritional Status

0008Ramadan fasting has drawn considerable interest

among nutritional scientists as it provides an excel-

lent opportunity to study the effects of restricted

energy intake and altered periodicity of meals on

changes in body weight, composition, fluid, and elec-

trolyte balance, and metabolic and biochemical

changes, especially those of serum lipid concentra-

tions in free-living populations. Most data are derived

from studies using small numbers of subjects who are

examined before and after the Ramadan fast. Rarely

are nonfasting control groups used to account for

seasonality or other changes that occur during the

month, nor are the long-term effects of these annual

fasts described.

Energy intake and weight changes during Ramadan

0009Fasting during Ramadan results in moderate body

weight losses in both men and women, primarily

due to declines in energy intake. Body weight de-

creases range between 0.3 kg and almost 2.5 kg,

with energy intake reductions, in some cases, as high

as 20–25%. Significant reductions in skinfold thick-

ness and elevation in plasma glycerol concentrations

suggest that decreased body fat may be the main

component of body weight loss. Decreased water

intake by more than half a liter per day can cause

dehydration, also contributing to a reduction in body

weight. A pattern of slower decline in weight ob-

served in a few settings may be attributed to meta-

bolic adaptation and reduction in physical activity

over time.

0010Although in general there is a reduction in body

weight during Ramadan fasting, some individuals or

4934 RELIGIOUS CUSTOMS AND NUTRITION

groups may experience no change, or in some cases,

even weight gain. The weight increase may be related

to increased consumption of foods high in sugars and

protein which is common during Ramadan. It is also

customary to eat meals with friends and relatives,

which is conducive to higher food intake. Further, a

decline in respiratory exchange ratio reflecting in-

creased mobilization of body fat is suggestive of a

metabolic adaptation to fasting.

0011 Dehydration due to abstinence from drinking fluids

over long periods of time during Ramadan has been a

cause for some concern, especially in hot tropical

climates. Negative fluid balance among fasting indi-

viduals is evident by increased hematocrit, serum

sodium, calcium, protein, creatinine, urea, and modi-

fied electrolyte balance. Increased concentration of

urine and decreased urine volume and salt retention

are some of the compensatory mechanisms to achieve

fluid balance. The season in which the month of

Ramadan falls may have a big effect on the evapora-

tive water loss that can occur. Studies have shown

conflicting results: some suggest no negative fluid

balance while others show this may be due to envir-

onmental factors such as temperature and humidity

of the place and season in which the studies were

carried out.

0012 The effects of Ramadan fasting on changes in

carbohydrate metabolism are not well-known. Al-

though fasting levels of glucose and insulin tend to

remain unchanged, or decline initially but then return

to normal later, circadian profiles of gastric pH,

plasma gastrin, insulin, glucose, and calcium are

modified during Ramadan. Increased concentrations

of urea and uric acid suggesting increased catabolism

have not always been confirmed.

0013 The effect of Ramadan fasting on plasma lipids

and lipoproteins has received some interest. Almost

consistent reports of no change in total cholesterol

and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) and

beneficial increases in high-density lipoprotein chol-

esterol (HDL-C), apo A-1, and apo A-1 to apo B ratio

are found. While these effects may be sustained for

about a month after Ramadan ends, the impact of

such transient annual changes on cardiovascular dis-

ease remains unknown and open for research.

Pregnancy and Lactation and Ramadan Fasting

0014 The rules of exemption from fasting in certain con-

ditions such as during pregnancy or while breast-

feeding an infant appear to have varying degrees of

acceptance and interpretation. In some cultures, preg-

nant women may either be unaware of this exemption

or may choose to fast with the rest of the family rather

than alone, at a later time, due to the inconveniences

of a different meal pattern and cooking. Cases of

unsuccessful lactation due to fasting have led to un-

hygienic alternatives being offered to the young infant

in lieu of breast milk, resulting in adverse health

effects. The effects of dehydration due to abstention

from drinking water during Ramadan on lactational

performance suggest that, although lactating women

may lose some of their total body water during

the daylight hours, plasma indices of dehydration

over a 24-h period remain in a normal range. This

may occur because women adapt by superhydrating

themselves overnight and by restricting urinary

output. Despite these mild changes in their state of

hydration, there may be marked changes in breast

milk osmolality, lactose, sodium, and potassium

concentrations, reflecting disturbed milk synthesis.

Accounts of drastic effects of fasting on young

breast-feeding infants is found in the 1930s when

severe forms of xerophthalmia (clinical signs of vita-

min A deficiency) occurred in infants whose mothers

participated in long-term religious fasts.

0015Scientific knowledge on the health and other

impacts of fasting during pregnancy is scant, although

metabolic consequences of fasting during pregnancy,

such as declines in concentration of serum glucose,

insulin, lactate, creatinine, and a rise in triglycerides

and hydroxybutyrate suggests a state of a phenom-

enon termed as ‘accelerated starvation.’ Although

pregnancy outcome, including birth weight of infants

whose mothers observed Ramadan fast during preg-

nancy, does not appear to be affected in affluent

settings, increased rates of low birth weight, still-

births, and perinatal mortality are observed among

populations living in poor, more stressful environ-

ments. It is hard to determine, however, whether the

adverse outcomes are a direct result of the fasting.

Interestingly, increased full-term births have been

recorded during the 25-h-long fast of Yom Kippur.

The Hindu Conception of Vegetarianism:

The Sacred Cow

0016In the pre-Aryan Indus valley civilization, it was the

bull, not the cow, that was venerated. Cattle were

prized assets and considered objects of worship, as

recounted in the hymns of Rig-Veda, the holy Hindu

scriptures written in 1500–100 bce. The Atharva-

Veda, which came later, is where the first accounts

of the prohibition of the slaughter of cows are found.

While meat eating was practiced, and cows were

occasionally slaughtered for guests and at times of

festivity, the sacredness of the cow, manifest as the

Vahan (carrier) of god Shiva became complete in the

great epic Mahabharata. Here the sanctity of a cow is

recognized and attributed to being a source of food

(milk), promoting fertility, removing evil influences,

RELIGIOUS CUSTOMS AND NUTRITION 4935