Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Regulations stipulate aging of ports at least 3 years in

cask or bottle prior to release.

Aging

0035 Port wine storage leads to varied changes in the wine

character and composition. The type and capacity of

containers are selected for the character evolution

required, but those from grapes also contribute.

Ports are aged under oxidizing conditions except for

vintage and late bottled vintage (LBV) products.

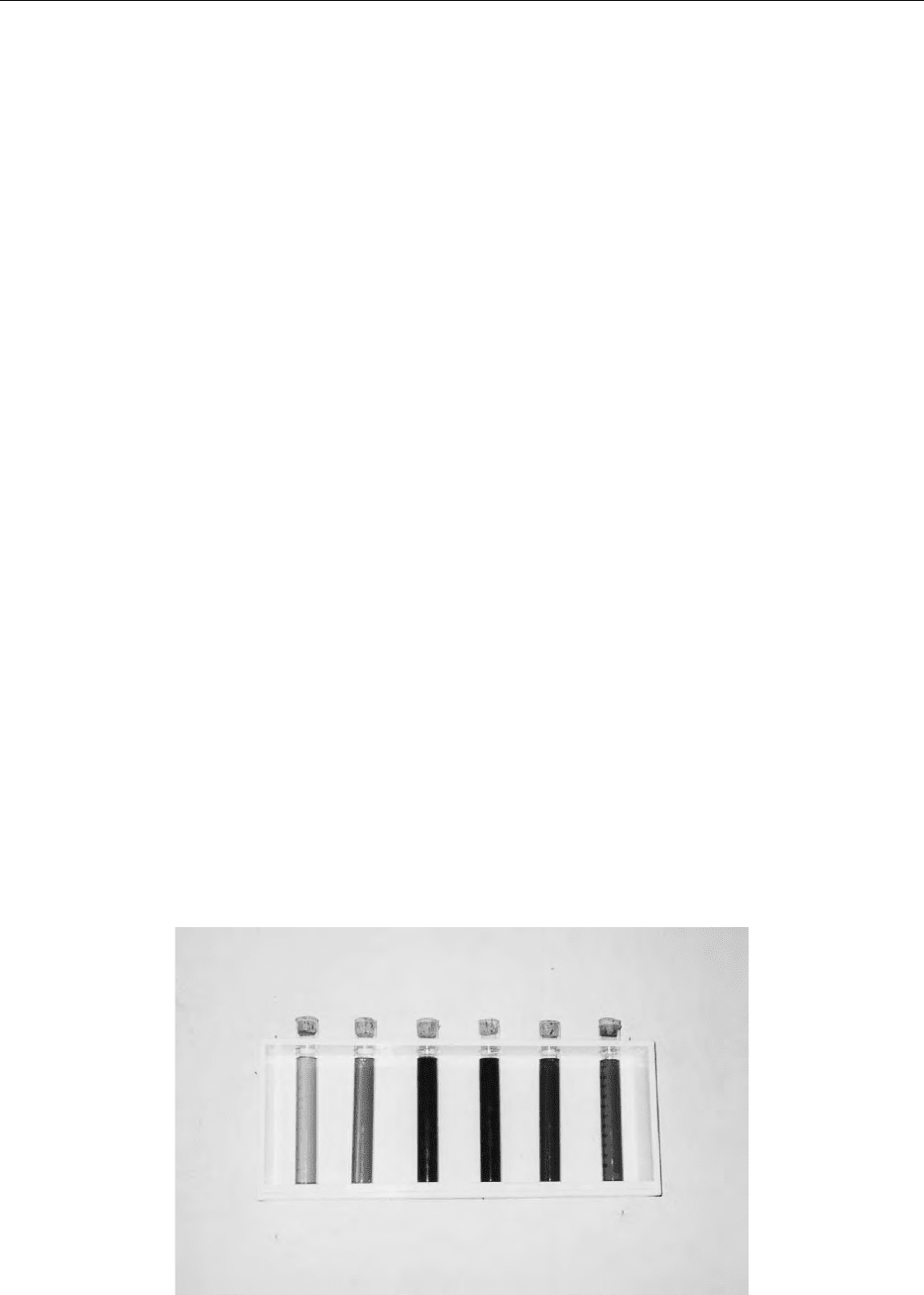

Young ports are blue–purple in color – gradually

turning red, then tawny and progressively paler with

age, eventually achieving amber and golden tones

(Figure 4). The aging method varies. All red ports

are aged for at least 2 years in oak casks and continue

maturation either in casks (ruby, tawny, aged taw-

nies) or in bottles (vintage, LBV). Ruby ports retain

an intense dark red color with the sensory character-

istics of young wines.

0036 Red ports are aged in wooden vats and pipes,

stacked four high to minimize evaporation. With

white ports, in order to avoid color gain through

prolonged wood maturation, concrete vats are used.

0037 With labor costs increasing, larger vats (5–400

pipes in capacity) are used more often for aging

wines. The rate of maturation is inversely related to

volume. As a consequence, wines are selected early

according to style requirements and then stored in

appropriately sized containers. Traditional lodges in

the Douro exhibit wine liquid temperature changes of

up to 20

C. The atmosphere is also dry, leading to

faster evaporation and maturation rates and baked or

maderized flavor notes. In Gaia, the relative humidity

is constant (approximately 54%), evaporation lower,

and temperature fluctuations under normal storage

conditions limited to 14–16

C. Maturation is slower,

producing fresher wines than the Douro.

Wood

0038Although the character of the grape variety is central

to wine flavor development, wood has been con-

sidered to play important roles in port maturation.

Staves are from local and imported oak (including

some used for Scotch whisky casks), chestnut, and

Brazilian mahogany. Dried fruits and spicy aroma

notes, and smooth mouthfeel (texture) characters,

attributed to lengthy wood maturations, characterize

premium tawny ports. Traditional guidelines for pro-

duction include the use of small oak pipes with fre-

quent racking to induce sufficient aeration. Contact

between the wood surfaces and the wine, regular

racking, and oxygen migration through the staves

have been reported to be important variables in port

maturation.

0039Unlike table wines, port is aged in a varied range of

container sizes. Wood is often reused many times,

depending on the style and cellar practice. New

wood is rarely used and, if required, is seasoned thor-

oughly with a second pressing wine, table wine, and/

or young red port before deployment. Consequently,

some experts believe that little woody character

should be detectable in ports, through the use of

extractive-depleted staves, except in the older tawnies

matured in the Douro.

0040LBV ports are stored in large vats, and tawny ports

are stored in pipes. Frequent racking with aeration of

wines influences maturation. Wood aging of such

wines is believed to be primarily an oxidative process

with limited parallel extraction of nonflavonoid phe-

nolics from stave lignins and tannin degradations.

fig0004 Figure 4 (see color plate 123) Samples of different types of port, showing the range of colors.

PORT/The Product and its Manufacture 4635

Wine maturation is thought to occur mainly from

evaporation and oxidation.

Fining and Stabilizing

0041 Fining, traditional for clarifying wines, removes a

certain amount of color and tannins to produce softer

and ‘older’ wines. Port is usually filtered: modern

methods have replaced the cloth bag method of sep-

arating wine from lees. Modern filters consist of a

series of woven nylon pads that allow lees to circulate

until the pads are evenly coated with solid material.

The resulting solid cake then acts as a filter that

introduces clarity in the wine. Bentonite may be

used with white wines to remove protein.

0042 Refrigeration is now used to stabilize wines:

chilling precipitates unstable coloring matter and the

potassium salts of tartaric acid. Chilled wine is passed

through a vessel that encourages deposition of potas-

sium hydrate tartrate. Chilling is followed by further

filtration (continuous refrigeration). There may be

wine retention in an insulated tank for up to a week

before filtering (Gasquet process). Finally, the clari-

fied product is passed through a plate heat exchanger

separated by thin stainless steel plates from incoming

wine at ambient temperature.

0043 Refrigeration and sulfur dioxide addition, prior

to bottling, allow wines to remain bright in bottle

for up to 18 months under normal storage condi-

tions. Brief pasteurization may also be used after

cold treatments. In addition, Kieselguhr with pad

filtration may be a final processing after fining or

refrigeration.

Bottling

0044In earlier years port was shipped in pipes to England

for transfer to squat and bulbous bottles, designed for

transporting wine from cask to table. Oxidation was

a problem, since stored on their side such bottles did

not allow cork contact. In 1775, bottles with longer

bodies and shorter necks, were introduced to allow

better storage. This change initiated the development

of bottle aged vintage ports.

0045By the 1930s, bottling had become more central-

ized as suppliers, instead of merchants, could now

bottle under customs and excise supervision. Duty

was not payable until port was declared from bond.

In the 1970s, more shippers began bottling under

their own labels instead of shipping in bulk. The

result was that it became possible to develop the

international brands that currently dominate the con-

sumer’s attention.

Port Styles

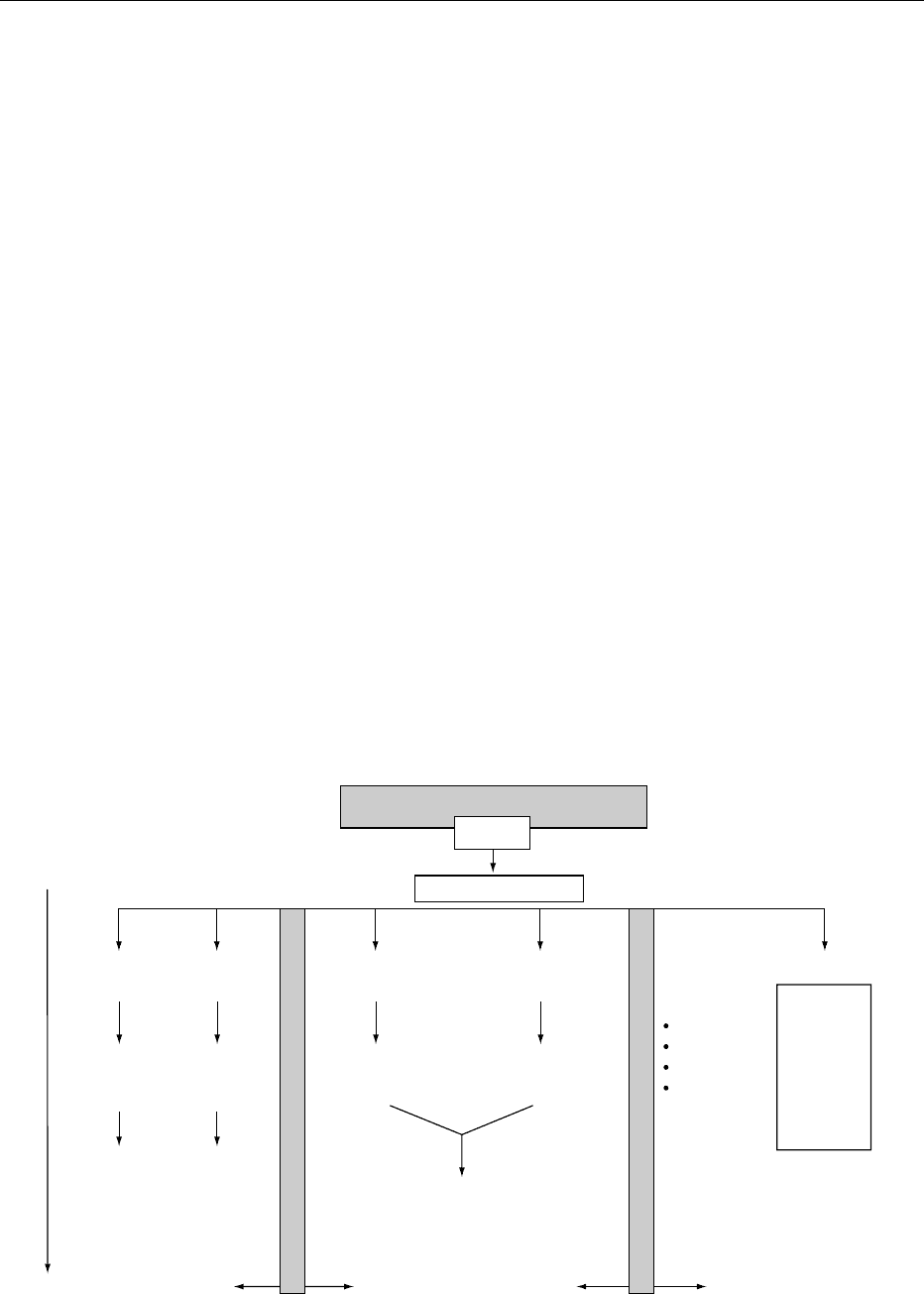

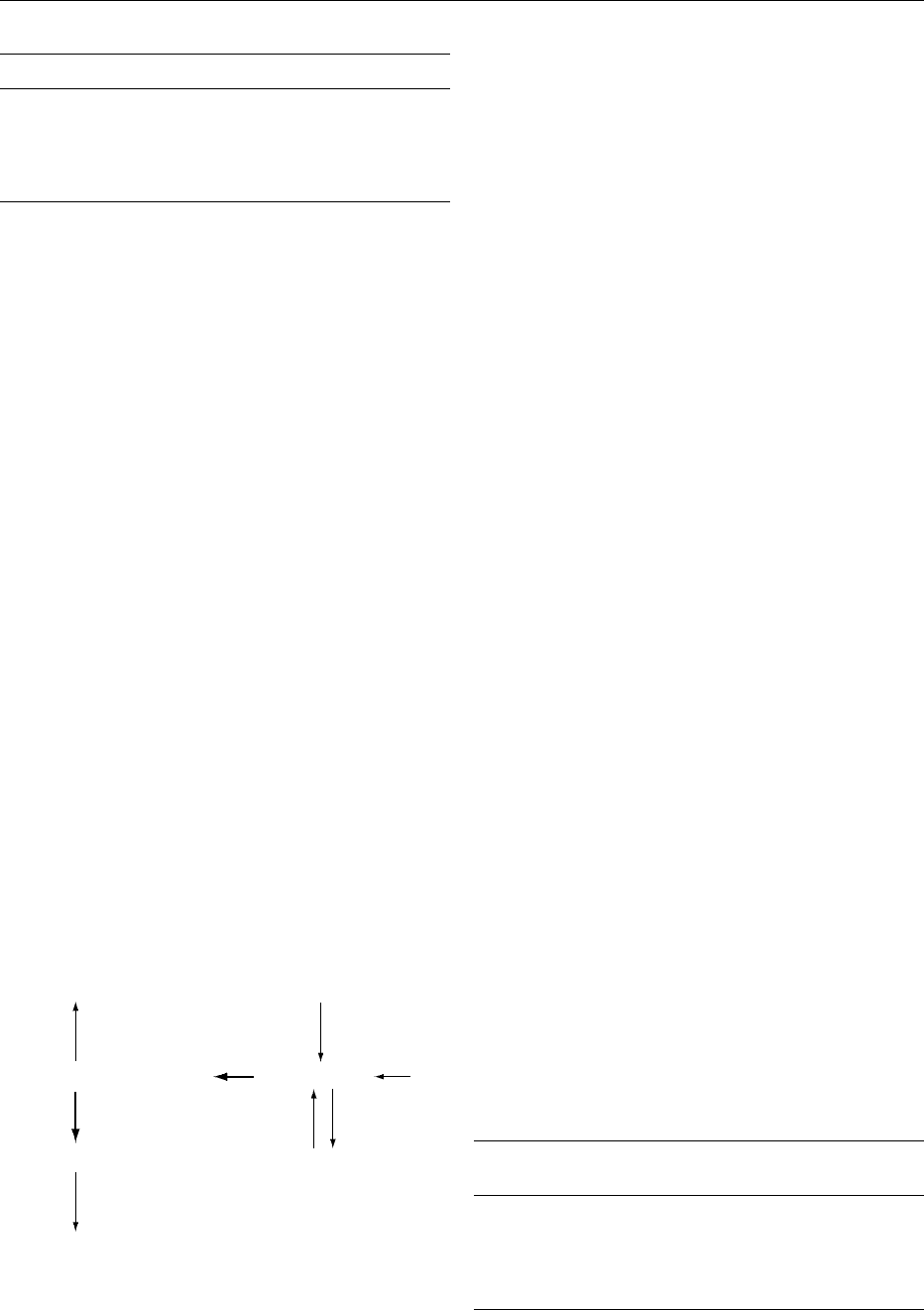

0046The IVP governs how producers may use labels to

describe port wines. There are four major premium

categories of port: vintage, LBV, quinta, and aged

tawny (Figure 5).

Maturation/Bottling

Port

Fermentation

Time

Vintage Single quinta

vintage

Late bottled

vintage

Dated tawnies

(colheits)

Aged tawnies

Ageing and

blending

in wooden

casks

10 years old

20 years old

30 years old

40 years old

Ruby

tawny

white

Blends of several years

2 years

in cask

2 years

in cask

4−6 years

in cask

At least 7 years

in cask

10−50 years

in bottle

Bottle−aged

8−10 years

Fined, bottled and sold

ready to drink

Bottle-aged ports Cask -aged ports Single years

fig0005 Figure 5 Processes involved in the different types of port production.

4636 PORT/The Product and its Manufacture

0047 Vintage ports are wines of a single harvest, pro-

duced in a specifically recognized year, and have sens-

ory characters regarded as exceptional. Such port

wines spend 2–3 years in wooden casks or vats prior

to bottling. The IVP has rights to descriptions of

vintage and corresponding dates. Subsequently, mat-

uration reactions occur in the bottle for 10–20 years

and in some cases up to 50 years, with little possibility

of oxidation. Such ports are never fined or filtered;

the wines generate precipitates, or ‘throw a crust,’

and require decanting prior to consumption.

0048 LBV ports are wines of a single harvest, aged in

wood for 4–6 years. Bottling is between 1 July of the

fourth year and 31 December of the sixth year. Bottle

maturation reactions may continue for 5 years or

more with continuing improvements. Traditional,

now rare, LBVs are not fined or filtered, and throw

a crust with improvements on bottle aging. However,

modern LBVs are treated to remove solids.

0049 Quinta are wines that come from grapes from a

single property, named on the label. Such ports are

made only in years not deemed good enough to de-

clare a vintage. Single Quinta vintage ports have been

available for some time, but currently, the market is

expanding to include this designation for both ruby

and tawny ports.

0050 Aged tawnies are typically matured for 10, 20, 30,

or 40 years, the average of ports blended. Old tawnies

have a characteristic gold color. Dated tawnies are

wines from single harvests, matured in oak casks for

at least 7 years with the harvest and bottling date

specified on the labels. A special reserve tawny con-

tains wines that have spent 3–4 years in the cask prior

to blending.

Wines Matured in Wood

0051 Wood-matured ports, such as tawnies, are treated

to encourage color lightening. Blend components

are racked at least once a year to remove deposits

and ensure oxygen dissolution. During the initial

years of aging, container size is thought to be of little

importance. Frequent use of wooden containers of

considerable size such as 650-l oak casks, or vats,

for short periods, stainless steel or tartaric acid-lined

tanks.

0052 Racking and the resulting wine aeration lead to

oxidation, essential for the maturation of these

port wines. During racking, more alcohol may be

added, or maturing wine may be ‘refreshed’ by adding

small quantities of younger wine. On creation of

the blend, to assist maturation, wines are usually

transferred to smaller vats or casks. When the desired

degree of maturity has been reached, the final stand-

ard blends, with sensory attributes specific to each

company, are prepared for bottling and export.

As noted previously, no port may be sold for con-

sumption in Portugal or abroad until it is at least 3

years old.

Wines Matured in Bottle

0053Vintage and LBV ports, bottled after only a few years

in casks, have sensory attributes that are more de-

pendent on must characters than on wine treatment.

Vintage ports are racked infrequently to prevent

excessive aeration, using smaller casks that are con-

sidered to provide a more controlled and uniform

aeration. Bottles are stored in dark cellars of constant

temperature with controlled ventilation and humid-

ity. Color loss occurs slowly compared with wooded

wines, and bottled ports retain their characteristic

fruitiness, retaining a full flavor and purple–red

colors for many years.

See also: Grapes; Port: Composition and Analysis

Further Reading

Bakker J (1986) HPLC of anthocyanins in port wines: de-

termination of aging rates. Vitis 25: 203–214.

Bakker J, Bellworthy SJ, Hogg TA et al. (1996) Two

methods of port vinification: a comparison of changes

during fermentation and of characteristics of the wines.

American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 47: 37–42.

Bakker J, Bridle P, Timberlake CF and Arnold GM (1986)

The colors, pigment and phenol contents of young port

wines: Effects of cultivar, season and site. Vitis 25:

40–52.

Bakker J and Timberlake CF (1985) An analytical method

for defining a Tawny port wine. American Journal of

Enology and Viticulture 36: 252–253.

Bakker J and Timberlake CF (1986) The mechanism of

color changes in aging port wine. American Journal of

Enology and Viticulture 37: 288–292.

Burnett JK (1985) Port. In: Birch GC and Lindley MG (eds)

Alcoholic Beverages, pp. 161–169. London: Elsevier

Applied Science.

Cristovam E, Paterson A and Piggott JR (in press a) Devel-

opment of a vocabulary of terms for sensory evaluation

of dessert port wines. Italian Journal of Food Science.

Cristovam E, Paterson A and Piggott JR (in press b) Differ-

entiation of port wines by appearance using a sensory

panel: comparing free choice and conventional profiling.

European Food Research and Technology.

Fletcher W (1978) Port: An Introduction to its History and

Delights. London: Philip Wilson.

Fonseca AM, Galhano A, Pimentel ES and Rosas JR-P

(1984) Port Wine. Notes on its History, Production

and Technology. Oporto: Instituto do Vinho do Porto.

Garcia-Viguera C, Bakker J, Bellworthy SJ et al. (1997)

The effect of some processing variables on non-coloured

phenolic compounds in port wines. Zeitschrift fu

¨

r

Lebensmitteluntersuchung und -forschung 205:

321–324.

PORT/The Product and its Manufacture 4637

Gowell RW (1972) The manufacture of port. Process Bio-

chemistry Oct.: 27–29.

Howkins B (1982) Rich, Red and Rare. The International

Wine & Food Society’s Guide to Port. London: William

Heinemann.

Reader HP and Dominguez M (1995) Fortified wines:

sherry, port and Madeira. In: Lea AGH and Piggott JR

(eds) Fermented Beverage Production, pp. 159–203.

London: Blackie Academic & Professional.

Robertson G (1992) Port. London: Faber and Faber.

Williams AA, Langron SP, Timberlake CF and Bakker J

(1984) Effect of colour on the assessment of ports. Jour-

nal of Food Technology 19: 659–671.

Composition and Analysis

E Cristovam, University of Adelaide, Adelaide,

Australia

A Paterson, University of Strathclyde, Scotland, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

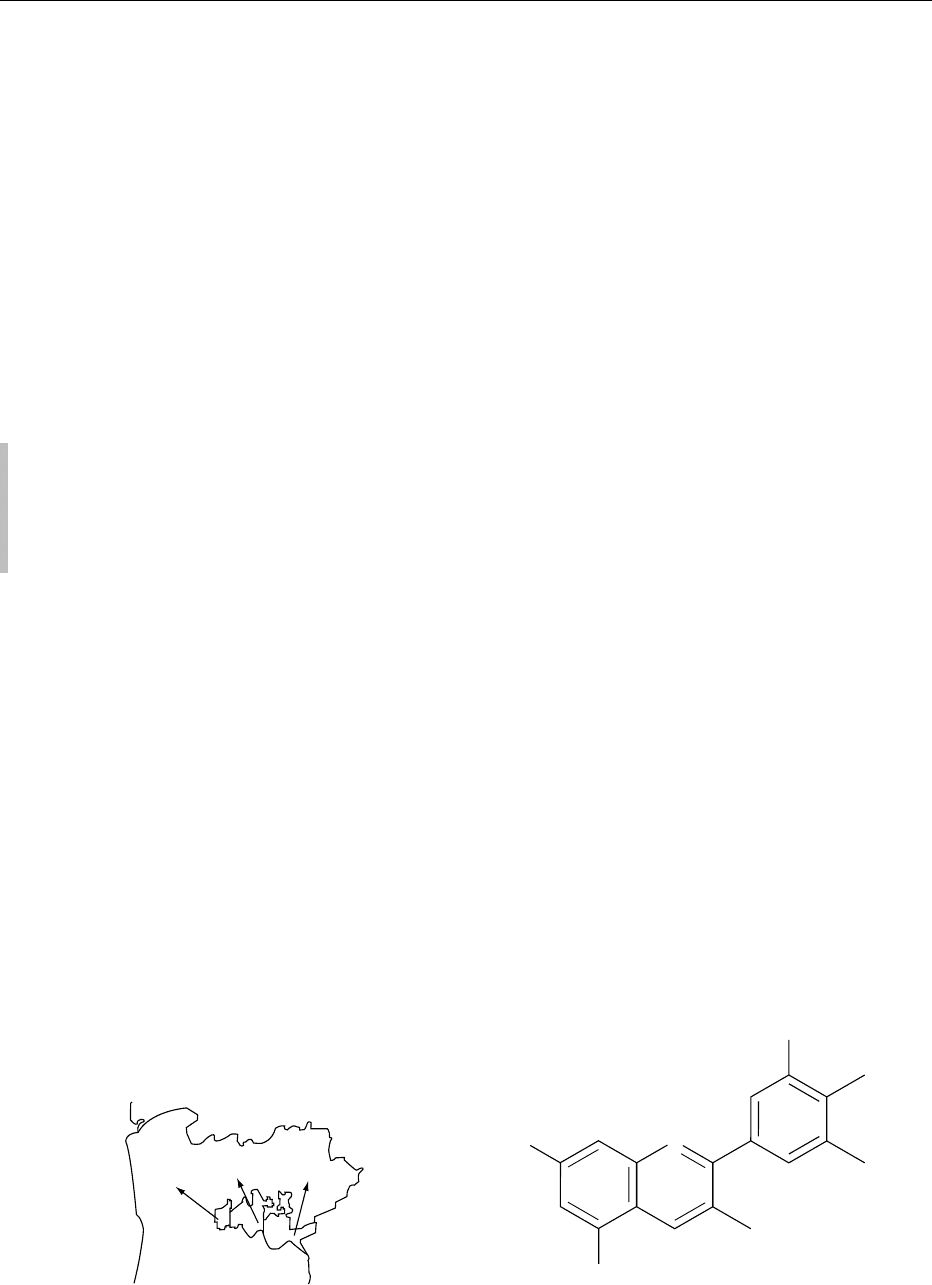

0001 The demarcated Douro region – established in 1756 –

consists of three subregions: Baixo Corgo, Alto

Corgo, and Douro Superior (Figure 1), each with

individual characters. Vines cover approximately

15% of this steep mountainous region, with the

Baixo Corgo dominating. Small vineyards can be

found throughout the region, with the larger mostly

located in the Douro Superior. Vineyards producing

grapes for port wines are graded on a point system,

biased towards environment – c. 75% for vine prod-

uctivity, altitude, soil, locality, and vine training, 14%

from grape cultivars and degree of site slope, and

> 10% from local features. Grape varieties favored

(around 7% points) include Tinta Francisca, Tinta

Ca

˜

o, Touriga Nacional, and Mourisco. Low-scoring

musts are utilized in table wines.

Oxidative Aging – Tawny Ports

0002Tawny ports, matured from 10 to 40 years and par-

ticularly important, have maturations dominated by

oxidative aging in wooden casks allowing oxygen

migration, supplemented by oxygenation during

frequent initial rackings. Small ‘pipes,’ as opposed

to large vats, insure high cask surface area-to-volume

ratios.

0003Reactions between wine congeners, together with

cask-derived components, are important. Congener

oxidations facilitate flavor evolution to characteristic

mellowness with dried fruits, caramel, and vanilla

notes. Most obvious, and dominating, are relation-

ships between aging and color, with oxidations of red

and purple anthocyanins, and losses as insoluble

precipitates that include tannins. Tawny ports have

yellow, amber, and tawny hues at intensities related to

maturation period and cask choice, at rates depend-

ent on original varietal choice and wine composition.

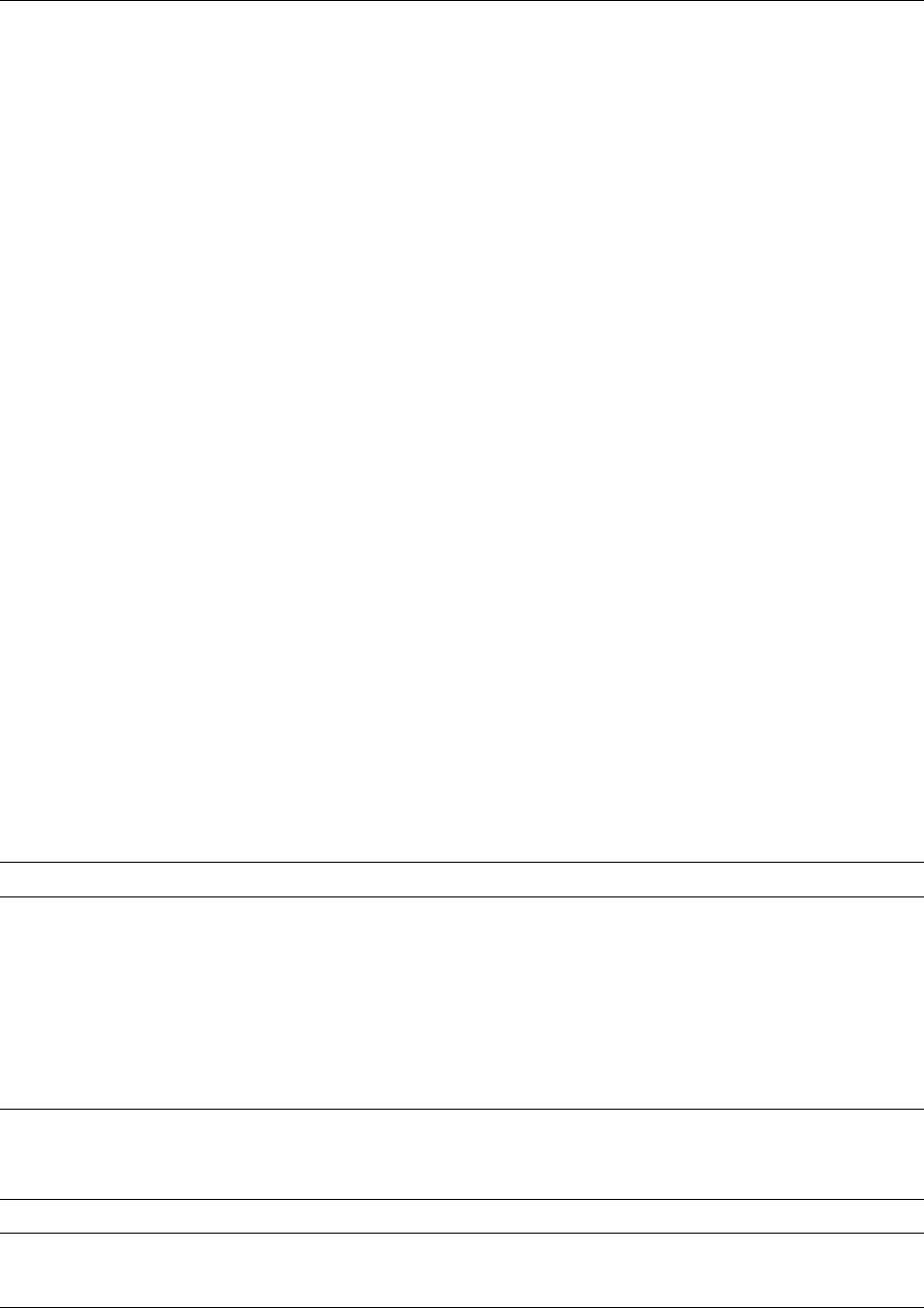

0004Reactions between acetaldehyde, anthocyanins

and catechins yield reddish-blue condensation pig-

ments that darken ports, ‘closing up,’ over the initial

6 months. Progressive lightening follows, with hue

changes and gradual browning from competing alde-

hyde-induced reactions and direct condensations of

anthocyanins with phenolics (Figure 2). Less is known

about wood contributions to tawny ports spending

over 50 years in old and recycled casks than

character in red table wines. For tawny ports, color

loss is essential and style-defining; in red wines it is

detrimental to quality. (See Antioxidants: Natural

Antioxidants.)

Nonoxidative Aging – Vintage Ports

0005Vintage ports age in bottles for up to 30 years. Initial

oxygen, absorbed during bottling, is slowly reduced

by reactions with anthocyanins and other wine

components. Color is lost more slowly than in cask

Baixo

Corgo

Portugal

Spain

Alto

Corgo

Douro

Superior

Atlantic ocean

fig0001 Figure 1 Regia

˜

o Demarcada do Douro – demarcated Douro

region.

HO

O

OH

OH

+

OCH

3

OCH

3

O-glucose

fig0002Figure 2 Oxidation/polymerization of phenolic components in

ports.

4638 PORT/Composition and Analysis

maturations and the initially full-bodied wines retain

flavor intensity, fruity characters, purple-red color-

ation, and freshness of youth for many years. Limited

oxidation reduces aldehyde formation, precipitation

of insoluble phenolic products, and leucoanthocya-

nins loss, yielding more condensed products.

0006 Vintage ports show direct relationships between

age and volatile acidity, and contents of ethyl acetate,

pentyl alcohols, and sodium. This is from either mat-

uration or modern wine-making strategies, including

reductions in air contact of grapes; introduction of

coating equipment; decanting without aeration;

replacement of sodium metabisulfite by SO

2

; and

quality control in fortifying grape spirit. Clear aging

effects include decreases in tartaric acid through

deposition of potassium hydrogen tartrate, in citric

acid content and total acidity, and increases in

glycerol content and changes in alcohols.

Oxidative Reactions

Formation of Esters

0007 In acidic, high-ethanol port wines, esterifications,

slow in table wines, proceed at rates influenced by

temperature and pH (pH 3.5–4.0), yielding ethyl

esters of organic acids – lactic, succinic, malic and

tartaric acids. Nonvolatile phenolics influence ester

solubilities in the aqueous ethanol, removing such

aroma-active congeners from head spaces, influen-

cing perceived character.

0008 Esters of higher (isoamyl, hexyl and 2-phenylethyl)

alcohols show inverse maturation relationships

through hydrolyses with equilibria functions of initial

concentrations, those of parent acids and storage

temperature. In aging, ethanol and acetaldehyde

oxidations yield acetic acid, influencing pH, ester

equilibria, and forming ethyl acetate. Such ester

formation appears central to desirable flavor

changes in fortified wines. (See Oxidation of Food

Components.)

Formation of Carbonyl Compounds: Aldehydes,

Acetals

0009 In maturations, important aldehydes are converted to

alcohols or combine with sulfur dioxide. Acetalde-

hyde is most abundant, but other aldehydes are de-

rived from carbohydrate (furfural, 5-methylfurfural,

and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural) or lignin degradations

(vanillin, syringaldehyde, coniferaldehyde, and sina-

paldehyde, cinnamaldehyde). Residual carbohydrates

(approximately 100 g l

1

) in port contribute to such

reactions.

0010 Furfural, acetaldehyde, and other higher aldehyde

contents can be directly related to maturation period,

especially at higher temperatures. Woody flavor char-

acters have been linked to aldehyde polymerization.

0011In acidic wines, acetals are principally formed

from reactions between monohydric alcohols, and

aldehyde carbonyl groups, notably of acetaldehyde.

Oxidations yield flavor-active aldehydes, notably

benzaldehydes, also contributing to acetal formation.

Other Reactions

0012Phenols derived from wood maturations include

guaiacol, phenol, m-cresol, eugenol, 4-vinylphenol,

and 4-vinylguaiacol. Lactones include b-methyl-

g-octactone. Wood-extracted aldehydes include

vanillin, syringaldehyde, coniferaldehyde, and sina-

paldehyde.

Classic Enological Analyses

Port Acidity

0013Total titratable acidity values of port wines at pH 7.0

range from 5.86 to 3.45 g l

1

as tartaric acid. Older

wines have increased volatile and total acidities

through acetic acid formation. In young ports, total

acidity is reduced by tartrate precipitation.

Volatile Acidity

0014Determined by official Office International de la

Vigne et du Vin (OIV) methods, volatile acidity is

dominated by acetic acid (around 90%) but propi-

onic, formic, and butyric acids also contribute. Such

acids are from yeast and lactic acid bacterial fermen-

tations and wood maturation reactions. Port wines

generally have volatile acidity values < 0.35 g l

1

acetic acid, although 1.02 g l

1

was recorded for a

40-year-old tawny and a 1960 Colheita tawny.

Organic acids

0015Grapes contribute tartaric and malic acids to wines.

Tartaric acid concentration varies during grape

ripening, and is more related to climatic conditions

than varietal character. Tartrate precipitation during

maturation decreases wine contents to 0.445–

1.688 g l

1

, independent of age or wine type.

0016In contrast, malic acid contents, more dependent

on grape variety than climate, fall during ripening.

Contents are lower in younger port wines, than older,

possibly through later picking in recent vintages.

0017Lactic acid, formed by strain-dependent anaerobic

yeast metabolism, is present in port wines in the range

0.3–1.68 g l

1

, independent of wine age.

0018Type differentiation was achieved on the basis of

contents of citric acid and alcoholic strength (Table 1)

in 21 red and four white ports, and six Spanish

PORT/Composition and Analysis 4639

port-style wines. Australian port-style wines have

higher ethanol contents. (See Acids: Natural Acids

and Acidulants.)

Alcoholic Strength

0019 Alcoholic strength (% v/v ethanol) in red ports ranges

between 19 and 22%, with white ports as low as

16.5% (light, dry white port). Spirit contributes about

20% initial volume to port wines; subsequent alcoholic

strength adjustments dilute wine congeners, and in-

crease precipitation of tartrates and extraction of wood

substances. Alcoholic strength changes with water and

ethanol evaporation through staves; it is dependent on

storage conditions and wine sugar content.

Sulfur Dioxide

0020 Total SO

2

is from summations of iodometric titra-

tions of free and bound components in acid condi-

tions after a standard pretreatment by the Portuguese

official method (Portaria 985/82 and pr NP-2220).

Values between 9 mg l

1

(Colheita tawny, cask wine)

and 99 mg l

1

(10-year-old tawny, commercial wine)

have been reported. In vinifications, SO

2

is added for

microbial stability and antioxidant properties. Free

SO

2

rapidly binds to ethanol but also hydrogen per-

oxide, produced during phenol oxidations, reducing

further oxidation.

Reducing Sugars and Glycerol

0021 Must origin and quality, shipper requirements, and

house style, all influence residual sugar content,

typically 80–120 g l

1

from the Lane-Eynon method.

0022Certain sweet red wine musts – geropigas – can be

150 g l

1

residual sugar; drier, more fermented musts

have 20–50 g l

1

. White geropigas are made for

blending or specialty products; dry white aperitif

ports contain < 50 g l

1

sugar. Glucose and fructose

concentrations range from 161 g l

1

(Colheita tawny,

cask wine) to 63 g l

1

(30-year-old tawny, commercial

wine). Fructose at 60–70 g l

1

is more abundant than

glucose (40–50 g l

1

).

0023Typical must specific gravities are 1090–1100 for

red and 1085–1095 for white ports; fermentations are

terminated around 1045. In Australian port-style

wines, specific gravities (20/20

C) of 1036 and

1080 make these even sweeter than the sweetest

port wines (Table 2).

0024The IVP (Instituto do Vinho do Porto) recognizes

classes of port wines, varying in sugar content

(Table 3).

0025Glycerol, the second most abundant alcohol, con-

tents are from 3 to 8 g l

1

. Glycerol acetals are found

as in other aged fortified wines, and trans 5 hydroxy-

methyl-2-methyl-1, 3-dioxolane in port.

Dry Extract, and Folin-Ciocalteu Index

0026Dry extract values are determined indirectly as dens-

ity of the residue without alcohol, following replace-

ment of alcohol with an equivalent volume of water

in the Portuguese norm (Portaria 985/82 and pr

NP-2222) and OIV methods. Values in Colheita

tawnies range from 120 to 188 g l

1

. Maturation

changes include: alcohol and water evaporations;

extractive increases; and precipitation of salts,

tbl0002 Table 2 Sugars in red and white ports, Spanish and Australian port-style wines

Portuguese redports Portuguese white ports Spanishport-styles Australian port-styles

Glucose (g l

1

) 30–48 41–44 24–49 76–118

Fructose (g l

1

) 48–67 53–59 32–52 93–148

Reduced sugars (g l

1

) 101–119 69–115 NA

NA, not analysed.

tbl0001 Table 1 Enological analyses of red and white ports and similar Spanish and Australian wine styles

Portuguese redports Portuguese whiteports Spanishport-styles Australian port-styles

Alcoholic strength (% vol) 18.6–21.5 19.5–19.9 16.9–19.0 22–23

pH 3.54–3.99 3.54–3.57 3.10–3.72 3.69

Total acidity (g l

1

) 1.81–3.04 2.06–2.63 2.26–3.09 NA

Volatile acidity (g l

1

) 0.12–0.49 0.16–0.25 0.26–0.41 NA

Phosphoric acid (g l

1

) 0.23–0.33 0.23–0.29 0.18–0.28 NA

Tartaric acid (g l

1

) 0.94–1.45 1.19–1.69 0.97–1.85 NA

Citric acid (g l

1

) 0.08–0.26 0.11–0.17 0.12–1.03 NA

Malic acid (g l

1

) 0.06–2.07 0.94–1.39 0.35–0.70 1.66–1.71

Lactic acid (g l

1

) 0.34–2.42 0.33–0.94 0.34–1.19 0.37–1.20

Succinic acid (g l

1

) 0.18–0.33 0.17–0.31 NA

NA, not analysed.

4640 PORT/Composition and Analysis

phenolic compounds, proteins, polysaccharides, and

other components.

0027 The Folin-Ciocalteu index, from European Eco-

nomic Community (EEC) recommended method

(EEC no. 2676/90), expresses wine total phenols

(anthocyanins, tannins, flavones, flavonols, cate-

chins, cinnamic acids, and related compounds).

Tannins and Phenolic Compounds

0028 Tannin levels in ports have been reported to between

400 and 600 mg l

1

.

0029 Color in ports, principally from soluble grape-skin

anthocyanins (Figure 3), is from malvidin (3-gluco-

side, 3-p-coumarylglucoside, and 3-acetylglucoside,

in decreasing order). Varietal differences in such com-

pounds are important. Aldehyde-bridged polymers of

anthocyanins and other phenolics dominate over

direct condensation of anthocyanins with phenolics,

through free aldehyde contents (50–100 mg l

1

)of

young ports. With aging, anthocyanins rapidly disap-

pear, replaced by polymers of progressively decreas-

ing absorbance, at rates depending on racking and

cask choice. Prolonged oxygen diffusion yields wine

of tawny coloration influenced by wood extractives

and composition.

0030 Wine aeration during filling and racking seems

more important for color changes than subsequent

oxygen diffusion from studies of varietal port wines

aged in miniature recycled-stave casks. The reduced

soluble extracts, including ellagic tannins, of recycled

wood suggest limited contribution to wine changes,

dominated by an evolution in phenolic components.

Port maturations are likely primarily driven by oxi-

dation, influenced by grape varietal differences, with

inert but permeable casks making little direct contri-

bution. (See Tannins and Polyphenols.)

Color Measurements

0031Spectrophotometric measurements at A

520 nm

and

A

420 nm

, yield tint (A

420 nm

/A

520 nm

), and color density

(A

520 nm

þ A

420 nm

) values and at natural pH specify

redness and brownness in color, respectively. CIELAB

(Commission Internationale de l’E

`

clairage) 76 L*a*b

values (hue, angle, and chroma), are high L* for

lightness and low for darkness; a* measures redness

and b* brownness. Total pigments and total phenols

can also be determined.

Metal Ions

0032Trace metal contents differentiate between Portuguese

ports and similar styles in wine from Spain. Rubidium

and manganese contents (Table 4) mirror soil differ-

ences, although rubidium varies with maceration in-

tensity, as can lithium, and manganese from vineyard

treatments. Iron and aluminum concentrations in

Spanish wines may also reflect soil differences.

Volatile Compounds in Port

0033Thirty-five volatile aroma components were quanti-

fied in 20-year and 100-year Australian port-style

wines with higher ethyl lactate (110–370 mg l

1

)

and diethyl succinate (61–130 mg l

1

) than in younger

wines. Only the former contributes to aroma. Trans-

b-methyl-g-octalactone (oak lactone) contents were

0.8–2.2 mg l

1

.

0034Furfural, 2-acetylfuran, 5-methyl furfural, ethyl

lavulinate, ethyl furoate, and 5-ethoxymethyl furfural

are derived from carbohydrate degradation, heating,

and prolonged storage. The older wine had more

volatile components from wood and carbohydrate

degradation.

tbl0004Table 4 Metal ions in red and white ports and Spanish port-

style wines

Portuguese

red ports

Portuguese

white ports

Spanish

port-styles

Rb (mg l

1

) 0.66–1.43 NA 0.00–0.44

Mn (mg l

1

) 0.77–1.32 NA 0.20–0.58

Al (mg l

1

) 0.09–1.81 NA 1.91–4.01

Fe (mg l

1

) 1.0–3.4 NA 3.6–7.4

Li (m gl

1

) 17–54 31–37 45–64

NA, not analysed.

tbl0003 Table 3 Sweetness in port wines

Sweetnesslevel Gravity

Baume

¤

Sugars (g l

1

)

Very sweet (La

´

grima) >1034 >5.0 >130

Sweet 1018–1033 2.8–5.0 90–130

Semidry 1008–1017 1.4–2.7 65–90

Dry 998–1007 0.0–1.3 40–65

Extra dry <998 0.0 <40

Ethanol + O

2

Nonaldehyde polymers

Acetaldehyde

SO

2

Anthocyanins + Flavan 3-ols

Polymerization

Aldehyde-bisulfite

Aldehyde-bridged

polymers

fig0003 Figure 3 Structure of malvidin 3-glucoside, an anthocyanin

occurring in grapes used for port wine production.

PORT/Composition and Analysis 4641

0035 In two commercial Portuguese ports, a ruby (young

wines retaining an intense dark-red color) and

a tawny, 141 volatile flavor components were

identified: 81 esters, 14 alcohols, 9 dioxolanes, 6

hydrocarbons, 5 acids, 5 carbonyls, 4 nitrogen com-

ponents, 3 hydroxy carbonyls, 2 phenols, 2 alkoxyal-

cohols, 2 alkoxyphenols, 2 halogen compounds, 2

lactones, 2 other oxygen heterocyclics, 1 sulfur

component, and 1 diol.

0036 Alcohols were most abundant, followed by esters,

dominated by ethyl esters and lower-molecular-weight

acetates, the latter increasing with maturation. The

tawny port was rich in flavor-active succinates (ap-

proximately 100 mgg

1

) from slow esterification and

trans-esterification reactions at wine pH and matur-

ation stave contact. Ethyl lactate was present at 15

and 30 mgg

1

in ruby and tawny ports, respectively,

and together with diethyl malate and succinate may

indicate age, as can acidic degradation of fructose

to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Other furan derivatives

contribute baked and caramelized flavor notes to

older wines. The flavor contribution of b-methyl-

g-octactone, important in oak-aging, is unclear in

port wines, as are relationships between maturation

and concentration of vitispirane (abundant in the

ruby; traces in the tawny).

0037 Reserva ports (single harvest without blending),

matured in wood under oxidative aging, show matur-

ation increases in diethyl succinate, ethyl acetate, etha-

nal, octanal, glyoxal, and methyl glyoxal (Table 5)and

also benzaldehyde (oxidation of the alcohol), trans-2-

octenal, 2-decanone, and 2-tridecanone, but inverse

relationships for acetoin and methanol.

0038 Differentiation of red ports (21) from similar Span-

ish wine (6) on the basis of volatiles concentrations

are shown in Table 6.

0039 Characteristic port volatile components are esters

and alcohols, the former dominated by ethyl esters,

acetates, and succinates. Older tawny ports are

rich in, and age-differentiated by, contents of

2-propenoic acid, diethyl succinate, butanedioic

acid, oak lactone, ethyl dodecanoate, isoamylbuty-

rate, 1-butanol, decanoic acid, and ethyl lactate,

amongst other components. Vintage ports have been

differentiated from late-bottled vintage (wines of a

single harvest, aged in wood for 4–6 years) from 3-

butanoic acid contents.

Flavor in Port Wines

0040Port wine flavors originate in the volatile and non-

volatile components in grapes, from fermentation or

maturation. Although ports have traditionally been

vinified using endogenous microflora, including a

range of yeasts and bacteria, there have been moves

towards encouragement of yeast mono- or at least

mixed cultures, for example Saccharomyces cerevi-

siae UCD 522. Butanol, isobutanol, and 1-hexanol

originate from yeast fermentation of carbohydrate

and amino acid sources; hexyl acetate and

2-phenethyl acetate are also fermentation products.

Ethyl lactate and diethyl succinate, resulting from

esterification reactions, increase in the wines due to

storage and long maturations. Oxidation reactions

originate mainly from benzaldehyde and ethyl-2-

phenylacetate, while 2-phenethanol and oak lactone

result from wood extraction.

0041Few published studies describe flavor components,

as opposed to volatiles. Young ports have notably

astringent flavor characters through high contents

of total and individual phenols with a harshness

mellowed by wood maturations. Older ports have

‘softer’ characters with increased flavor complexity.

0042Flavor characters evolve through oxidation and

polymerization of solution nonvolatile phenolic

tbl0005 Table 5 Concentration of volatile compounds in two

Portuguese Reserva ports

Reservaports

1968 1991

Glyoxal (mgl

1

) 1302.9 669.7

Methyl glyoxal (mgl

1

) 1981.2 898.1

Diethyl succinate (mg l

1

) 16.3 2.2

Methanol (mg l

1

) 202 213

Ethanal (mg l

1

) 78.3 94

Ethyl acetate (mg l

1

) 40.4 48

Acetoin (mg l

1

) 27.6 64.3

Octanal (mgl

1

) 128 79.7

Benzaldehyde (mgl

1

) 561.9 83.4

Tr a n s -2-octenal (mgl

1

) 291.8 90.2

2-Decanone (mgl

1

) 71.2 13.7

2-Tridecanone (mgl

1

) 91.5 65.8

tbl0006Table 6 Volatile congeners in red ports and Spanish port-style

wines

Portuguese

red ports

Spanish

port-styles

Methanol (mg l

1

) 259–360.3 113.6–275.8

Propanol (mg l

1

) 46.9–66.4 15.9–43.9

Isobutanol (mg l

1

) 93.3–146.7 21.7–30.0

2-methylbutanol (mg l

1

) 62.7–97.1 14.9–23.2

3-methylbutanol (mg l

1

) 237.4–344.1 54.0–92.8

Hexanol (mg l

1

) 3.5–6.6 1.0–2.3

Other higher alcohols (mg l

1

) 477.6–701.3 137.7–220.6

Propanol/isobutanol (mg l

1

) 0.40–0.57 0.72–1.83

Isoamylacetate (mg l

1

) 0.33–0.56 0.13–0.33

Octanoic acid (mg l

1

) 0.56–1.34 0.24–0.66

Ethyl hexanoate (mg l

1

) 0.17–0.49 0.11–0.26

Ethyl octanoate (mg l

1

) 0.33–0.69 0.09–0.27

Other esters (mg l

1

) 0.53–1.30 0.22–0.53

4642 PORT/Composition and Analysis

compounds, changing partitioning of aroma-active

components between wine head spaces and liquid.

The products of oxidations of congeners and ethanol,

depolymerizations and extraction of wood compon-

ents all influence partitioning. Grape varietal charac-

ter is central to flavor development, but wood aging

provides oxidative processes and nonflavonoid phe-

nolics from lignin and tannin degradations determin-

ing final character.

0043 Relating key sensory attributes to concentrations

of volatile flavor components would assist under-

standing of port wine character. Partial least-squares

(PLS) regression has facilitated modeling relation-

ships between compositional factors and age in vin-

tage ports. Certain variables (A-I, Table 7) showed a

low modeling power (32–49%) in predicting age,

while others (J–S) contributed greatly (above 70%).

Wine aging is generally understood as polyphenol

evolution, using Sudraud, Garoglio, and other indices

including color evolution. The importance of car-

bonyl compounds in vintage port wine aroma has

also been recognized.

0044 In further PLS modeling of ports, clear relation-

ships between sensory data and concentrations of

head space components, and between sensory and

nonvolatile component data, support hypotheses

that changes in nonvolatile phenolics influence the

perception of flavor character through changing

head space congener concentrations. Relationships

were also established between such components and

total maturation age, through oxidation and poly-

merization of wine compounds. Prediction of

intensity of certain flavor notes has also been possible

from solution concentrations of congeners, notably

for caramel and smooth characters. (See Flavor

(Flavour) Compounds: Structures and Characteris-

tics; Sensory Evaluation: Aroma.)

Port and Replica Wines Production

0045With the success of the Portuguese product, there

have been a number of attempts to produce similar

wines, including Starboard, in other countries,

notably Australia, California, and South Africa. In

2001 port sales were healthy, suggesting a good

future. However, non-Portuguese producers have

been required, with changes in international trading,

to stop the use of the port descriptor in the labeling

of their fortified wines and future exports look

problematic.

See also: Alcohol: Properties and Determination; Grapes;

Port: The Product and its Manufacture; Tannins and

Polyphenols

Further Reading

Bakker J and Timberlake CF (1986) The mechanism of

color changes in aging port wine. American Journal of

Enology and Viticulture 37: 288–292.

Bakker J, Bridle P, Timberlake CF and Arnold GM (1986)

The colors, pigment and phenol contents of young

port wines: Effects of cultivar, season and site. Vitis 25:

40–52.

Bakker J, Bellworthy SJ, Hogg TA et al. (1996) Two

methods of port vinification: a comparison of changes

during fermentation and of characteristics of the wines.

American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 47: 37–42.

Burnett JK (1985) Port. In: Birch GC and Lindley MG (eds)

Alcoholic Beverages, pp. 161–169. London: Elsevier

Applied Science.

Cristovam E, Paterson A and Piggott JR (2000) Develop-

ment of a vocabulary of terms for sensory evaluation of

dessert port wines. Italian Journal of Food Science 2:

129–142.

Cristovam E, Paterson A and Piggott JR (2000) Differenti-

ation of port wines by appearance using a sensory panel:

comparing free choice and conventional profiling. Euro-

pean Food Research Technology 211: 65–71.

Curvelo-Garcia A (1988) Controlo de Qualidade dos

Vinhos. Portugal: Odivelas.

Fonseca AM, Galhano A, Pimentel ES and Rosas JR-P

(1984) Port Wine. Notes on its History, Production

and Technology. Porto: Instituto do Vinho.

Garcia-Viguera C, Bakker J, Bellworthy SJ et al. (1997) The

effect of some processing variables on non-coloured phen-

olic compounds in port wines. Zeitschrift fu

¨

rLebersmittel

Untersudnung und Forschung A,205:321–324.

Gowell RW (1972) The manufacture of port. Process Bio-

chemistry Oct.: 27–29.

Table 7 Variables used to model vintage age prediction

Variable Code

Alcoholic grade A

Volatile acidity B

Total acidity C

Glycerol D

Ethyl acetate E

Pentyl alcohols F

Tartaric acid G

Citric acid H

Na I

DO420 J

DO520 K

Sudraud’s index (IC) L

Tone (TON) M

Garoglio’s aging index (IE) N

Anthocyanins O

Tone (H*) P

Chroma (C*) Q

Clarity (L*) R

Saturation (S) S

Tone (H*), chroma (C*), clarity (L*), and saturation (S) are four CieLab

parameters.

PORT/Composition and Analysis 4643

Howkins B (1982) Rich, Red and Rare. The International

Wine & Food Society’s Guide to Port. London: William

Heinemann.

Ortiz MC, Sarabia LA, Symington C, Santamaria F and

Iniguez M (1996) Analysis of ageing and typification of

vintage ports by partial least squares and independent

modeling class analogy. The Analyst 121: 1009–1013.

Reader HP and Dominguez M (1995) Fortified wines:

sherry, port and Madeira. In: Lea AGH and Piggott JR

(eds), Fermented Beverage Production, pp. 159–203.

London: Blackie Academic and Professional.

Williams AA, Lewis MJ and May HV (1983) The volatile

flavour components of commercial port wines. Journal

of Science and Food Agriculture 34: 311–319.

Williams AA, Langron SP, Timberlake CF and Bakker J

(1984) Effect of color on the assessment of ports. Journal

of Food Technology 19: 659–671.

Postharvest Deterioration See Spoilage: Chemical and Enzymatic Spoilage; Bacterial Spoilage;

Fungi in Food – An Overview; Molds in Spoilage; Yeasts in Spoilage

POTASSIUM

Contents

Properties and Determination

Physiology

Properties and Determination

M A Amaro Lo

´

pez and R Moreno Rojas, University

of Co

´

rdoba, Co

´

rdoba, Spain

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 Potassium is a light, soft metal and a strong reducing

agent, discovered by Davy in 1807 in caustic potas-

sium (KOH). It is widely distributed in minerals such

as sylvin (KCl), carnallite (KMgCl

3

or MgCL

2

KCl),

langbeinite (K

2

Mg

2

(SO

4

)

3

) or polyhalite (K

2

Ca

2

Mg

2

(SO

4

)

4

2H

2

O). Potassium is a very abundant metal

and is the seventh most abundant element in the

earth’s crust (2.59% corresponds to potassium in

the combined form). Sea water contains 380 p.p.m.

of potassium, making this mineral the sixth most

abundant in solution.

0002 Potassium is used extensively, mainly in the form of

potassium salts, in various fields such as medicine

(iodide as a disinfectant), photographic processing

(carbonate), explosives (chlorate and nitrate as

powder), defreezing agents, poisons (potassium cyan-

ide), metallurgy and basic chemistry (hydroxide in,

for example, strong bases, oil sweetening, CO

2

absorbent, chromate and dichromates as oxidants,

carbonate in glass industry), fertilizers (nitrate, car-

bonate, chloride, bromide, sulfate), detergents and

soaps (hydroxide and carbonate), coolants in nuclear

reactors (NaK alloy), etc.

0003Potassium (atomic number ¼19) forms part of

the group of alkali metals classified between

sodium (atomic number ¼11) and rubidium (atomic

number ¼37). It has an atomic weight of 39.098,

oxidation state 1 and an electronic orbital structure

of [Ar] 4s

1

. This electronic configuration (one elec-

tron in the 4s orbital) enables potassium to ionize

easily to the cation K

þ

owing to the loss of its most

external electron. It does not appear as a native metal

in nature. Potassium exists in nature in three isotopes:

39

K (93.26%),

40

K (0.0117%) and

41

K (6.73%).

40

K

is radioactive and responsible for most of the natur-

ally occurring internal radioactivity in the body. This

property enables researchers to monitor total body

potassium values as a function of age and disease.

0004The behavior of potassium in its metallic form is

very similar to that of sodium, with which it is closely

related, both being alkali metals essential for life owing

to their involvement in cellular physiological develop-

ment and the regulation of body fluids, together with

4644 POTASSIUM/Properties and Determination