Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

0008 Insecticides Insecticides are represented by a variety

of different chemical classes involving a variety of

mechanisms of toxic action on insects as well as

mammals such as humans. Examples of mechanisms

of action include metabolic interference of the ner-

vous or muscle systems, desiccation, and sterilization.

Common types of insecticides include the chlorinated

hydrocarbons, organophosphates, carbamates, and

pyrethroids.

0009 The first major synthetic class of insecticides, the

chlorinated hydrocarbons, was developed during the

1930s and 1940s. Representative members of this

insecticide class include DDT, aldrin, dieldrin, and

chlordane. The chlorinated hydrocarbons are very

potent nerve toxins to insects, and their initial use

led to significant improvements in insect control.

Their high insect potency, combined with generally

low mammalian toxicity, provided excellent selectiv-

ity and insect control that was further enhanced by

their high environmental persistence. In subsequent

years, however, their resistance to environmental

decay, coupled with their widespread continuing

use, resulted in environmental build-up and food-

chain magnification that resulted in significant envir-

onmental and ecological damage. Today, very few

chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides remain regis-

tered for use in the USA, because of environmental

concerns, although their use may still be significant in

many areas of the world. Many recent studies have

also associated chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides

with potential adverse effects on human and nontar-

get organism fertility and reproduction arising from

enzyme-inducing or estrogenic properties of the

chemicals.

0010Historically, many of the uses of chlorinated hydro-

carbon insecticides were replaced by the organophos-

phate and carbamate insecticides. In contrast to the

chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides, the organo-

phosphates and carbamates break down quite rapidly

in the environment following application. They also

have a far greater acute toxicity in mammals. The

organophosphates and carbamates are derived as

esters of two very different chemical families but

share a common mechanism of toxicological action

tbl0002 Table 2 Common pesticide classes and representative

examples

Pesticide Examples

Insecticides

Chlorinated hydrocarbons Dicofol, methoxychlor, DDT,

aldrin, chlordane

Organophosphates Parathion, malathion,

chlorpyrifos, azinphos-

methyl

Carbamates Aldicarb, carbaryl, carbofuran

Pyrethroids Permethrin, cypermethrin

Herbicides

Triazine Atrazine, simazine, cyanazine

Phenoxy 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T, MCPA

Quaternary ammonium Paraquat, diquat

Benzoic acids Dicamba

Acetanilides Alachlor, metolachlor

Ureas Linuron

Fungicides

Inorganic Sulfur

Ethylenebisdithiocarbamates Maneb, mancozeb, zineb

Chlorinated phenols Pentachlorophenol

Herbicides/Plant growth regulators

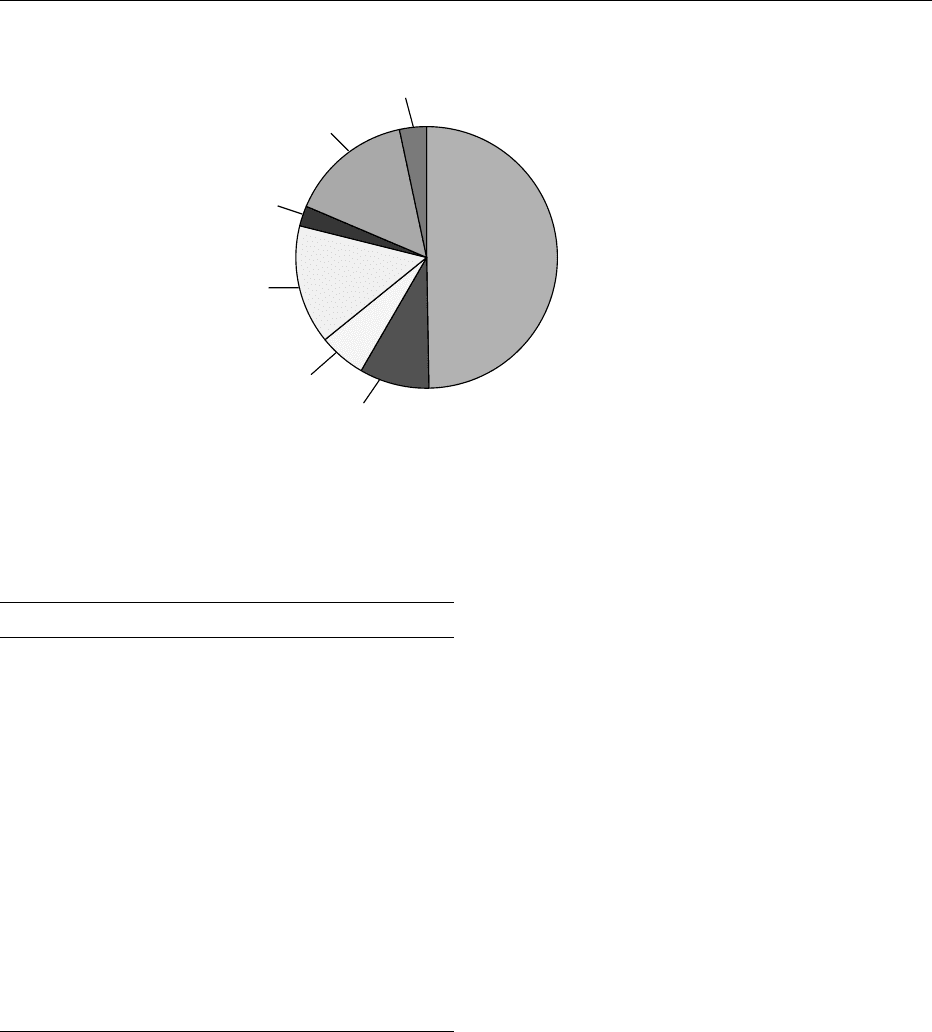

213 million kg

49.8%

Insecticides/Miticides

37 million kg

8.7%

Fungicides

24 million kg

5.6%

Fumigants/Nematicides

64 million kg

14.9%

Other (Conventional)

11 million kg

2.6%

Other (Non-conventional)

14 million kg

3.2%

Sulfur/Oil

65 million kg

15.3%

Total does not equal 100% due to

rounding

fig0001 Figure 1 Agricultural use of pesticides in the USA, 1997.

PESTICIDES AND HERBICIDES/Toxicology 4495

in both insects and mammals that involves inhibition

of cholinesterase enzymes that can disrupt the ner-

vous system.

0011 A newer class of insecticides, the pyrethroids, are

synthetic derivatives of pyrethrins (natural extracts

from chrysanthemums) that are made to be more

light-stable than their natural predecessors and thus

more effective as insecticides. The pyrethroids were

introduced in the 1970s and have broad-spectrum

activity against many insects while possessing a

much lower mammalian toxicity than the organo-

phosphates or carbamates. The pyrethroids are fre-

quently used in agricultural pest control, but their

use is still limited by their environmental lability,

relatively high cost, and their tendency to lose

effectiveness through the development of insect

resistance.

0012 Herbicides Several different types of herbicides

exist (Table 2), and each type has its own mechanism

of toxic action on weeds. Since weeds and mammals

differ dramatically in terms of metabolic function,

herbicides targeting specific metabolic pathways in

weeds frequently have little effect, and therefore a

low relative toxicity, in mammals including humans.

0013 The timing of herbicide application may determine

significantly whether the potential exists for con-

sumers to be exposed to herbicide residues in foods.

Some herbicides (preplant herbicides) are applied

before a crop is planted, whereas others (preemergent

herbicides) are applied after planting but prior to

the appearance of weeds, and others (postemergent

herbicides) are used after the weeds have germinated.

Some herbicides have broad-spectrum activity that

makes them toxic to most types of plant life, in-

cluding the crop being produced. One such example

is glyphosate. Recent developments in genetic engin-

eering have led to the development of varieties of

soy, corn, and cotton that are resistant to glyphosate,

meaning that glyphosate applications made while the

crop is growing will control weeds without affecting

the crop.

0014 Other herbicides, such as the phenoxy herbicides

(2,4-D, MCPA) are more selective in their toxicity;

they are toxic to broad-leaf plants but not to narrow-

leaf plants such as grasses. Some epidemiological

studies have suggested links between agricultural

worker exposure to phenoxy herbicides and certain

types of cancer.

0015 Fungicides A wide number of different types of fun-

gicides are available for use in agriculture (Table 2).

Fungicides control molds and other plant diseases by

interfering with the growth and/or metabolic pro-

cesses of fungal pests. In addition to improving crop

yields, fungicides may provide human health benefits

by reducing the production of mycotoxins (naturally

occurring toxins produced by fungi living on the food

crop) such as aflatoxins and fumonisins.

0016Pesticides suspected as carcinogens The potential

carcinogenic (cancer-causing) effects of many pesti-

cides have generated considerable public concern and

regulatory scrutiny. Although the consumption of

foods containing pesticide residues has not been cor-

related with the development of human cancers, some

epidemiological studies have linked the occupational

use of specific pesticides with the development of

cancers. Most pesticides considered as carcinogens,

however, owe their status as suspected carcinogens to

the results of long-term animal toxicology studies in

rodents such as rats and mice.

0017The carcinogenic potential of pesticides and other

chemicals is typically determined through long-term

animal bioassay studies. In these studies, animals are

frequently given a high dose (the maximum tolerated

dose, or MTD, that may cause considerable toxicity

but does not reduce life expectancy), a lower dose

(commonly one-half to one-fourth of the MTD),

and a control (zero) dose. Relatively high doses of

chemicals are given to the animals to maximize the

potential to identify toxicological effects such as

tumor production.

0018The amounts of pesticides that cause cancer in

animal studies frequently exceed the amounts that

humans are exposed to from the diet by several orders

of magnitude. It has been argued that many pesticides

considered to be carcinogens receive such classifica-

tion because of the high doses used in the long-term

animal studies and that the results of such studies may

not be applicable to human exposure to much lower

levels of the pesticides. As an example, it is well

established that high-dose toxicity may lead to in-

creased rates of cell proliferation that in itself is linked

to the development of cancer in laboratory animals.

Human exposure at lower levels of exposure would

not be expected to trigger such a response and, as a

result, would not be expected to lead to the develop-

ment of cancer.

0019Long-term animal studies are also prone to incon-

clusive and/or contradictory results among different

test animals and under different conditions. As a

result, the EPA has developed a weight-of-the-evidence

evaluation scheme based upon results of any human

data and animal testing to determine the likelihood

of a pesticide to be carcinogenic. A list of several

pesticides considered by the EPA to be ‘probable’

carcinogens is provided in Table 3. Some pesticides

may receive classification a ‘possible’ carcinogens,

whereas many others are considered noncarcinogens.

4496 PESTICIDES AND HERBICIDES/Toxicology

Regulating and Monitoring Pesticide Residues in

Foods

0020 The use of pesticides does not necessarily imply that

food residues will occur. Many pesticides are applied

to nonfood crops, whereas others such as broad-spec-

trum herbicides could damage or eliminate a crop if

misapplied. The timing of the pesticide application is

another important factor; many pesticides are applied

to food crops prior to the development of edible

portions of the crop, whereas other pesticides used

on food crops may not result in residues, because of

rapid environmental degradation between the time of

application and the time of harvest.

0021 Pesticide residue regulation In cases where the use

of a pesticide on a food crop may present the potential

to leave a residue in the USA, a maximum permitted

allowable residue level, or tolerance, is established.

Tolerances are specific to combinations of pesticides

and commodities; it is possible for the same pesticide

to have different tolerance levels established on dif-

ferent commodities, and several different pesticide

tolerances for distinct pesticides may be established

on the same commodity.

0022 Although it may seem counterintuitive, pesticide

tolerances are not based upon safety but rather repre-

sent the maximum expected residue of a pesticide on

a particular commodity resulting from the legal use of

a pesticide. The maximum levels are determined from

the results of controlled field studies performed by the

pesticide manufacturer using the ‘worst legal case’

conditions such as the maximum recommended ap-

plication rate, maximum number of applications per

growing season, and harvesting at the minimal antici-

pated time following harvest. Pesticide manufacturers

typically petition the EPA to establish the tolerances

at or slightly above the highest levels determined from

the controlled field studies. As such, the values

selected for tolerances are determined solely on the

basis of agricultural practices but not as a result of

human health risk assessments. Pesticide tolerances

therefore should be considered to represent enforce-

ment tools to determine whether pesticide applica-

tions may have been made in accordance to legal

requirements; in cases where residues exceed the es-

tablished tolerances, it is likely that such residues

resulted from misapplication of the pesticides. Such

a finding, however, rarely constitutes an ‘unsafe’ resi-

due according to standard toxicological criteria.

Pesticide tolerances, therefore, should be viewed as

enforcement tools but not as standards of safety.

0023Before the EPA grants a tolerance, human health

risk assessments are performed to determine the con-

ditions for acceptable pesticide use. Such conditions

include the listing of commodities on which a specific

pesticide may be used, the target pests controlled by

the pesticide, application requirements, and the ac-

ceptable interval between application and harvest. In

the EPA’s assessment of acceptable levels of consumer

exposure to pesticides, it considers potential human

exposure from all registered (and proposed) uses of the

pesticide. If the resulting risk is deemed to be excessive,

the EPA will not allow tolerances to be established for

specific commodities. If the risks are considered to be

acceptable, the tolerances are established, as discussed

in the preceding paragraph.

0024The processes that the EPA uses to determine the

acceptability of dietary pesticide risk are quite com-

plicated and subject to ongoing evolution to meet

the needs of new regulations, improved toxicology

testing, and advances in computational methods.

0025The first step in evaluating the consumer risks from

pesticide residues involves making estimates of the

amount of consumer exposure. The maximum legal

exposure to the pesticide is frequently calculated by

assuming that (1) the pesticide is always used on all

food items for which it is registered and/or proposed

for registration, (2) all residues on the food items

will be present at the established or proposed

tolerance levels, and (3) there will be no reduction

in residue levels resulting from postharvest effects

such as washing, cooking, peeling, processing, and

tbl0003 Table 3 Some pesticides considered to be ‘probable’

carcinogens by the US Environmental Protection Agency

Pesticide Pesticide type

Acetochlor Herbicide

Aciflourfen sodium Herbicide

Alachlor Herbicide

Amitrol Herbicide

Cacodylic acid Herbicide

Chlorothalonil Fungicide

Creosote Wood preservative

Cyproconazole Fungicide

Fenoxycarb Insect growth regulator

Folpet Fungicide

Heptachlor Insecticide

Iprodione Fungicide

Lactofen Herbicide

Lindane Insecticide

Mancozeb Fungicide

Maneb Fungicide

Metiram Fungicide

Oxythioquinox Insecticide

Pentachlorophenol Fungicide

Pronamide Herbicide

Propargite Insecticide

Propoxur Insecticide

Terrazole Fungicide

Thiodicarb Insecticide

TPTH Fungicide

Vinclozolin Fungicide

PESTICIDES AND HERBICIDES/Toxicology 4497

transportation. This approach leads to the calculation

of the theoretical maximum residue contribution

(TMRC). Although studies have indicated that the

TMRC values may overestimate the actual consumer

exposures by factors of 100–100 000, the TMRC

provides a starting point from which to estimate con-

sumer risks.

0026 In practice, the TMRC is compared with estab-

lished toxicological criteria such as the reference

dose (RfD) or the acceptable daily intake (ADI) that

represent, following analysis of animal toxicology

data and extrapolations to human health, the daily

exposure levels that do not constitute an appreciable

level of risk. In cases where the EPA determines that

exposure to a pesticide at the TMRC is below the RfD

or ADI, the risks for the pesticide are typically

deemed to be negligible, and the EPA allows toler-

ances to be established for the pesticide on specific

commodities. For pesticides that are considered as

potential carcinogens, the EPA also requires that the

quantitative carcinogenic risk to the pesticide be

below one excess cancer per million using models

that calculate possible human risks from low levels

of exposures to potentially carcinogenic pesticides.

Such models are developed from the results from

long-term studies on animals given high doses of the

pesticides. In cases where the exposures at the TMRC

exceed the RfD or ADI, or in cases where the carcino-

genic risks at the TMRC exceed one excess cancer per

million, the EPA may adopt a refined risk assessment

that more accurately expresses exposures. Such re-

finements may include adjustments of actual pesticide

use, the use of more realistic pesticide residue data,

and consideration of postharvest effects that may

significantly reduce residue levels prior to consump-

tion. In cases where the refined exposure estimates are

below the RfD or ADI and where the carcinogenic

risks at the refined exposure estimates are below one

excess cancer per million, the EPA will typically allow

tolerances to be established.

0027 The processes by which the EPA determines human

risks from pesticide exposure became more compli-

cated following the passage and adoption of the Food

Quality Protection Act (FQPA) of 1996. It is clear that

the new requirements of FQPA will require scientists

to develop improved methods for assessing risks to

pesticides and that once such methods are adopted,

the regulatory requirements may be much more strin-

gent and may lead to reductions in the amounts and

types of pesticides that may be used on food crops.

0028 Prior to FQPA, the EPA allowed tolerances to be

established on a chemical-by-chemical basis and con-

sidered only exposures resulting from dietary path-

ways. FQPA now requires the EPA to establish

tolerances only when the risks posed by pesticides

represent a ‘reasonable certainty of no harm.’ In de-

termining what constitutes this ‘reasonable certainty

of no harm,’ the EPA must now consider the aggregate

exposure to pesticides from dietary, drinking water,

and residential sources as well as the cumulative ex-

posure from pesticides possessing a common mechan-

ism of toxic action. As such, the EPA may consider the

risks from entire families of chemicals rather than the

risks from individual chemicals. Another important

provision of FQPA is the so-called 10 factor, which

requires the EPA to consider applying an additional

10-fold uncertainty factor in cases where infants or

children may be more susceptible to the toxicological

effects of pesticides than adults. The application of the

full 10 factor would result in a subsequent reduc-

tion in the RfD by a factor of 10.

0029Internationally, many countries adopt the Codex

Alimentarius maximum residue limits (MRLs),

which, like the US tolerances, exist primarily as en-

forcement tools to determine if pesticide applications

are made following good agricultural practices. Al-

though many US tolerances and Codex Alimentarius

MRLs are identical, there are many cases in which

the US tolerances are more restrictive and many

others in which the Codex Alimentarius MRLs are

more restrictive.

0030Pesticide residue monitoring Authority In the US,

the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has the

primary responsibility for enforcing tolerances in do-

mestic and imported foods. Domestic food samples

are frequently collected near the source of production

or at the wholesale level, whereas imported food

samples are typically taken at the point of entry into

the US. The types and quantities of samples taken by

FDA are determined by a variety of factors such as

regional intelligence on pesticide use, the dietary im-

portance of specific foods, information on the

amount of foods that enter interstate commerce, and

pesticide use patterns. Samples are analyzed using

multiresidue methods capable of detecting over 200

individual pesticides.

0031The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) also has

a role in pesticide residue monitoring, as it is respon-

sible for the monitoring of meat, poultry, and egg

products. It also conducts the Pesticide Data Program

(PDP), which collects residue data on fruits, vege-

tables, and processed foods. Findings from the

USDA’s PDP are considered to be more representative

of the actual food supply than those collected from the

FDA’s regulatory monitoring programs and are com-

monly used by EPA to aid in its risk-assessment efforts.

0032US monitoring of pesticide residues also occurs at

the state level. The largest state pesticide regulatory

and monitoring program exists in California, and

4498 PESTICIDES AND HERBICIDES/Toxicology

several other states, including Texas and Florida, have

significant pesticide-monitoring programs.

0033 Residue findings The most recent FDA pesticide

monitoring residue data are available for 1999.

During that year, FDA analyzed 9438 food samples

for pesticide residues. More samples were taken from

imported foods (6012 samples, or 63.7%) than from

domestic foods (3426 samples or 36.3%).

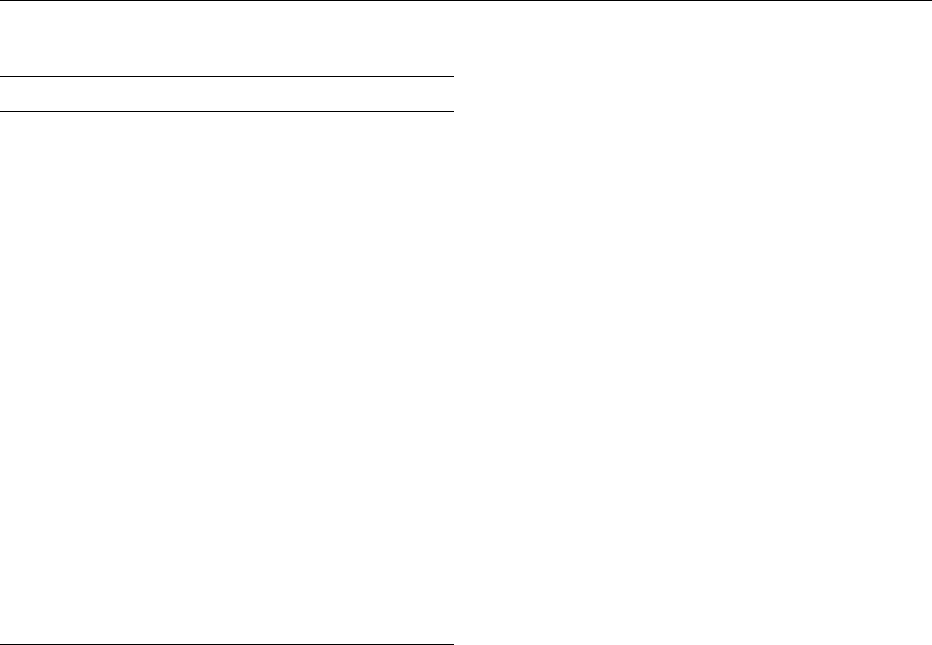

0034 The results of FDA’s 1999 monitoring of pesticide

residues in imported foods are shown in Figure 2.

Overall, 65.0% of the samples showed no detected

residues, and violations were identified in 3.1% of the

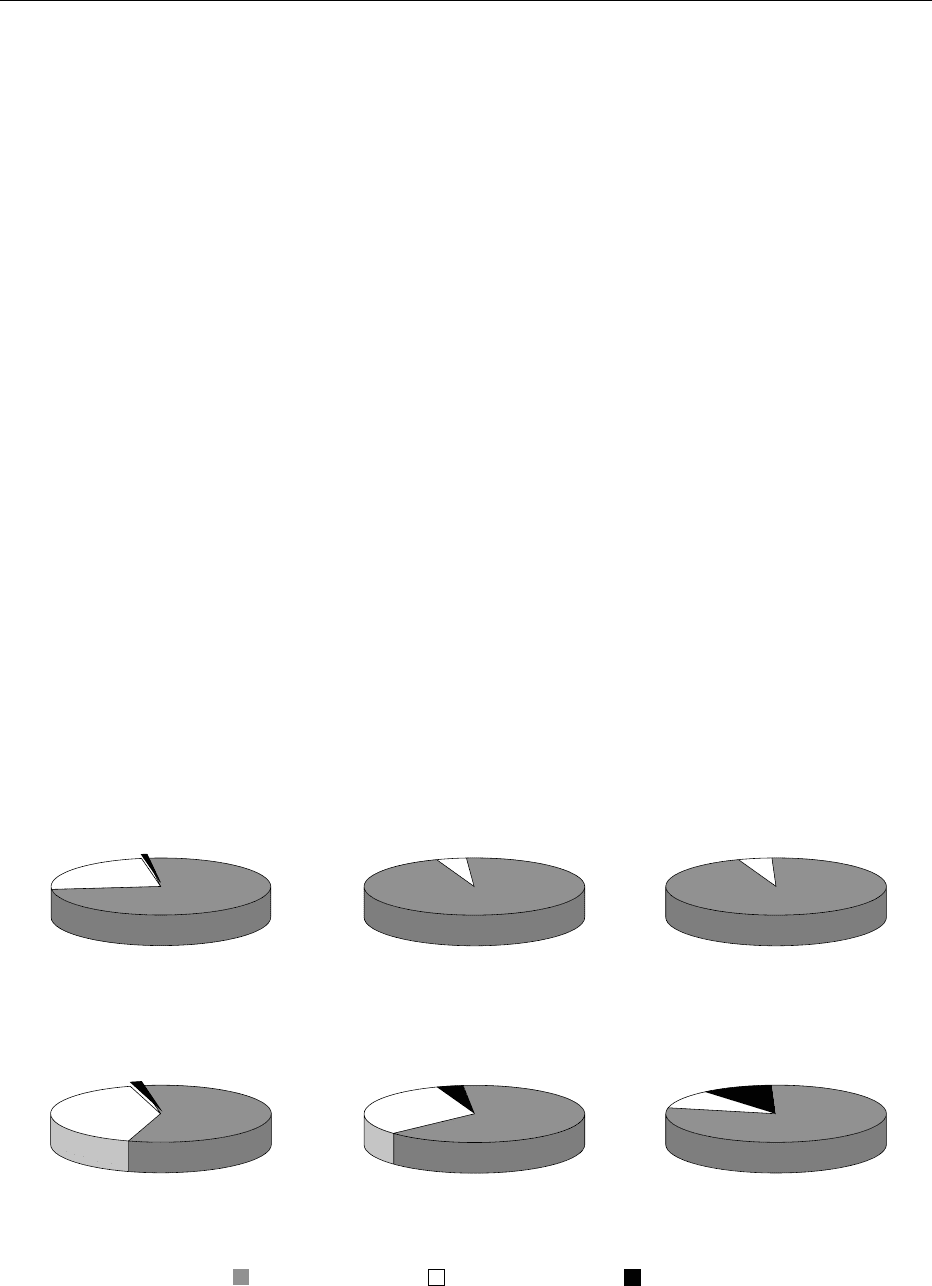

samples. Figure 3 shows the comparable results from

domestic foods where 60.2% of the samples showed

no detectable residues, and violations were present in

0.8% of the samples.

0035 Pesticide residue violations commonly take one of

two forms. The most common form of a violative

residue results when residues of a pesticide are

detected on a commodity for which no tolerance has

been established. This type of violation may result

from application of the pesticide to the wrong com-

modity, uptake from soil contaminated from a prior

use of the pesticide on a different commodity, or drift

of a pesticide from an adjacent field. The other type of

violation results when residue levels are detected in

excess of the established tolerance. In 1999, 90% of

the import violations occurred where residues were

detected on commodities for which tolerances were

not established, and only 10% of the violations

represented residues in excess of the tolerance. For

domestic samples, 69% were detected on commod-

ities for which tolerances were not established, and

the remaining 31% of violations occurred when levels

exceeding tolerances were detected. Fruits and vege-

tables were responsible for the highest percentages of

residue detections and the greatest number of viola-

tions from both imported and domestic foods.

0036Results obtained from California’s 1997 Market-

place Surveillance Program were quite similar to

those of the FDA’s 1999 monitoring. This program

analyzed 5660 samples in 1997, with 62.2% of those

originating from California, 6.7% from other US

states, and the remaining 31.1% from other coun-

tries. The majority of samples (62.1%) showed no

detectable residues, whereas 36.7% of the samples

contained legal residues. Violations were detected in

1.2% of the samples, and only 12% of the violations

represented residues detected in excess of tolerances.

The violation rate from imported foods was 2.4%,

and the violation rate for domestic foods was 0.7%.

0037The USDA’s PDP analyzed 9125 food samples for

pesticide residues in 1999. Foods analyzed included

apples, cantaloupe, cucumbers, grape juice, lettuce,

oats, pears, spinach, strawberries, sweet bell peppers,

tomatoes, winter squash, and corn syrup. Most of

the samples (8637) were from fruits and vegetables,

with lower numbers of samples collected for oats

(332) and corn syrup (156). The majority of samples

(79%) was of domestic origin. Overall, 36% of the

samples contained no detectable residue, whereas

57.5%

1.8%

40.7%

Grains and grain products

276 samples

Milk/Dairy products/Eggs

22 samples

Fruits

2290 samples

Vegetables

2768 samples

No residue found Residue found

not violative

Residue found

violative

Other

358 samples

Fish/Shellfish

Other aquatic products

298 samples

23.9%

4.5%

95.5%

5.0%

95.0%

3.9%

64.8%

31.3%

10.6%

78.8%

10.6%

75.4%

0.7%

fig0002 Figure 2 Results of US Food and Drug Administration monitoring of imported foods for pesticide residues, 1999.

PESTICIDES AND HERBICIDES/Toxicology 4499

26% contained one residue, and 35% contained more

than one residue. Residues exceeding the tolerance

level were detected on 0.3% of the samples, and

residues of pesticides were detected on commodities

for which no tolerances of the pesticides were estab-

lished on another 3.7% of the samples.

Dietary Risks from Exposure to Pesticides in Food

0038 A common method used to discuss the potential

human health risks arising from the consumption of

pesticide residues in the diet is to report on the results

of regulatory monitoring programs, as has been done

in the previous paragraphs. Results indicate that a

large percentage of food samples contain no detect-

able residues and that violation rates are relatively

low, particularly for foods grown in the US. Fre-

quently, the recitation of such findings is used as

justification for a lack of significant human health

risks resulting from pesticide residues in foods.

0039 The problem with adopting such an approach is

that it ignores the important, yet confusing, fact that

pesticide tolerances are not safety standards but

rather represent the maximum legal residues expected

when pesticides have been used according to direc-

tions. Taking this a step further, violative residues

should not be considered to be unsafe residues in

most cases but merely represent cases in which pesti-

cides have been misapplied or have been transported

to commodities for which they are not registered.

Although cases of pesticide misuse have historically

resulted in a small number of incidents of acute

poisoning of people consuming tainted foods, it can

be reasonably argued that the vast majority of viola-

tive pesticide residues do not represent significant

health threats to consumers based upon common

toxicological and risk assessment criteria.

0040A more accurate approach for estimating human

dietary risks from pesticides is to use exposure data

derived from market basket surveys rather than regu-

latory monitoring data. The FDA, for example, per-

forms its Total Diet Study annually. This study uses a

market basket approach, with each market basket

containing more than 250 individual food items.

Foods are collected by FDA inspectors from three

cities in each of the four geographical regions of the

USA and are prepared for table-ready consumption

prior to analysis for pesticide residues. By combining

analytical results from estimates of typical consump-

tion rates of the various food items or their com-

ponents, it is possible to estimate the typical daily

exposure of members of the general population to

specific pesticides as well as to break the population

down further into subgroups defined by factors such

as age, gender, and geographical location.

0041Although the FDA no longer makes its dietary

pesticide exposure estimates from its Total Diet

Study available to the public, results reported from

the 1991 Total Diet Study indicate that, for most

pesticides in a variety of different population sub-

groups, the typical daily exposure estimates represent

only a small fraction (often less than 1%) of the

corresponding RfDs or ADIs. To put this into some

level of perspective, it should be noted that typical

RfDs are derived by first identifying the highest level

of exposure to a pesticide that causes no noticeable

0.2%

61.3%

38.5%

2.6%

97.4%

28.9%

71.1%

0.6%

38.8%

60.6%

1.2%

69.7%

29.1%

1.4%

75.5%

23.1%

Grains and grain products

468 samples

Milk/Dairy products/Eggs

116 samples

Fruits

1063 samples

Vegetables

1414 samples

No residue found Residue found

not violative

Residue found

violative

Other

147 samples

Fish/Shellfish

Other aquatic products

218 samples

fig0003 Figure 3 Results of US Food and Drug Administration monitoring of domestic foods for pesticide residues, 1999.

4500 PESTICIDES AND HERBICIDES/Toxicology

signs of toxicity in laboratory animals and then div-

iding that level by an uncertainty factor (usually 100)

that presumably covers potential variability resulting

from the animal to human extrapolation and from

interhuman variability. Exposure at a level of 1% of

the RfD represents an exposure 10 000 times below

the level that does not produce noticeable effects

in the animals. Such findings provide an illustration

of why the majority of health professionals consider

the typical human health risks from pesticides in the

diet to be much lower than food safety risks posed by

such factors as microbiological contamination of

foods, nutritional imbalance, environmental contam-

inants, and naturally occurring toxins. The risks from

pesticides in the human diet are clearly not zero, since

consumption of tainted foods has caused documented

human illnesses throughout the world, and concerns

remain regarding potential long-term effects of diet-

ary pesticide exposure.

0042 It is also clear that the potential health benefits

resulting from pesticide use should be considered.

Pesticide use has resulted in increases in production

of a wide variety of food crops, which translates into

greater availability and lower consumer costs and

thus a greater potential consumption of agricultural

products. Epidemiological studies have clearly indi-

cated that diets rich in consumption of fruits, vege-

tables, and grains may significantly decrease one’s

risk of heart disease and certain types of cancer. The

US National Academy of Sciences, among other sci-

entific bodies, has concluded that the theoretical in-

creased risks from pesticide exposure resulting from

increases in consumption of fruits, vegetables, and

grains were greatly outweighed by the health benefits

of these foods.

See also: Cancer: Epidemiology; Carcinogens in the Food

Chain; Carcinogens: Carcinogenic Substances in Food:

Mechanisms; Food and Drug Administration; Food

Poisoning: Classification; Pesticides and Herbicides:

Types of Pesticide; Types, Uses, and Determination of

Herbicides

Further Reading

Fong WG, Moye HA, Seiber JR and Toth JF (1999) Pesti-

cide Residues in Foods: Methods, Techniques, and Regu-

lation. New York: John Wiley.

Hayes WJ and Laws ER (1991) Handbook of Pesticide

Toxicology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

National Research Council (1987) Regulating Pesticides

in Foods: The Delaney Paradox. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press.

National Research Council (1993) Pesticides in the Diets of

Infants and Children. Washington, DC: National Acad-

emy Press.

Tweedy BG, Dishburger HJ, Ballantine LG and McCarthy J

(1991) Pesticide Residues and Food Safety: A Harvest of

Viewpoints. Washington, DC: American Chemical Soci-

ety Symposium Series No. 446.

Winter CK (1992a) Pesticide tolerances and their relevance

as safety standards. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharma-

cology 15: 137–150.

Winter CK (1992b) Dietary pesticide risk assessment.

Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicol-

ogy 127: 23–67.

Winter CK (2001) Contaminant regulation and manage-

ment in the United States: The case of pesticides. In:

Watson DH (ed.) Food Chemical Safety, Volume 1: Con-

taminants, pp. 295–313. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead.

Winter CK and Francis FJ (1997) Assessing, managing, and

communicating chemical food risks. Food Technology

47: 85–92.

PH – PRINCIPLES AND MEASUREMENT

D Webster, Formerly of University of Hull, Hull, UK

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Background

0001 pH measurements have been, and continue to be,

widely used as a rapid, accurate measure of the acid-

ity of fluids of all sorts. There are two methods

for measuring pH: colorimetric methods using

indicator solutions or papers, and the more accurate

electrochemical methods using electrodes and a

millivoltmeter (pH meter). The development of the

glass electrode, which is convenient to use in a variety

of environments, and the development of the pH

meter have enabled the widespread application of

pH measurement and control to take place. The de-

termination, and hence the control of pH, is of great

importance in the food industry.

Basic Theory

0002In water, molecules (H

2

O) are in equilibrium with

hydrogenions(H

þ

)andhydroxideions(OH

)(eqn(1)).

PH – PRINCIPLES AND MEASUREMENT 4501

H

2

O Ð H

þ

þ OH

:ð1Þ

This ionization is of great importance in the chemistry

of aqueous systems, as it enables water to give or take

H

þ

ions, as required, by other dissolved substances.

0003 Applying the law of mass action to eqn (1):

½H

þ

½OH

=½H

2

O¼constant ;ð2Þ

where [] indicates the concentration in units of moles

per cubic decimeter (mol dm

3

).

0004 In pure water and dilute solutions, the concentra-

tion of the undissociated water may be considered

constant, hence ½H

þ

½OH

¼K

w

, where K

w

is a con-

stant called the ionic product of water.

0005 The ionic product varies with temperature, but at

about 25

C, its value is 10

-14

mol

2

dm

-6

(K

w

(0

C) =

10

14.9

, K

w

ð25

CÞ¼10

14 :0

, K

w

ð60

C Þ¼10

13 :0

).

This means that in pure water, the ionization is

very small. As the concentrations of H

þ

ions and

OH

ions are equal in pure water, and as

H

þ

OH

½¼10

14

mol

2

dm

6

at 25

C, H

þ

(or

OH

½Þ¼10

7

mol dm

3

.

0006 To be strictly correct, eqn (1) should be written as

eqn (3):

2H

2

O Ð H

3

O

þ

þ OH

, ð3Þ

where the H

þ

ion is attached to a water molecule to

form the oxonium ion (H

3

O

þ

). However, the symbol

H

þ

will be used throughout this article.

0007 When, in a solution, there are an equal number of

H

þ

and OH

ions, the solution is said to be neutral,

when there is an excess of H

þ

ions (> 10

7

mol dm

3

at

25

C), it is acidic, and when there is an excess of OH

ions ([H

+

<10

7

mol dm

3

), it is basic or alkaline.

pH Scale

0008 Although concentrations of H

þ

and OH

ions in

acidic and alkaline solutions can be expressed in

these molar concentrations, a much more convenient

method was introduced by So

¨

rensen in 1909. He

proposed the use of the H

þ

ion exponent pH, defined

by the relationship pH ¼log

10

½H

þ

. (This may also

be expressed as ½H

þ

¼10

pH

). To be strictly correct,

this equation is pH ¼log

10

ð½H

þ

=½1), as a loga-

rithm must be dimensionless. From this, it can be

seen that pH does not have units – the often-used

expression ‘pH unit’ is wrong.

0009 Using the pH scale, a change of 1 corresponds

to a 10-fold change in the H

þ

ion concentration,

a change of 2 corresponds to a 100-fold change,

etc. The pH scale has the advantage that all

solutions from 1 mol dm

3

acid to 1 mol dm

3

alkali can be expressed by positive numbers from 0

to 14. Thus, at 25

C, a neutral solution, which has

H

þ

¼ 10

7

mol dm

3

,hasapHof7,a1moldm

3

solution of a strong (completely ionized) acid such

as hydrochloric acid, which has H

þ

¼ 1 ¼ 10

0

mol dm

3

, has a pH of 0, and a 1 mol dm

3

solution

of a strong (completely ionized) alkali acid such as

sodium hydroxide, which has OH

½¼1 mol dm

3

,

hence H

þ

¼ K

w

= OH

½¼10

14

mol dm

3

, has a

pH of 14. pH values below 0 and above 14 occur in

solutions of strong acids and alkalis of strengths

greater than 1 mol dm

3

.

0010As K

w

varies with temperature, pH measure-

ments should be made at about 25

C. The pH of

a neutral solution at 0

C is 7.45 (K

w

¼ 10

14:9

,

H

þ

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

10

14:9

p

¼ 10

7:45

mol dm

3

, and at 60

C,

the pH is 6.5 (K

w

¼10

13.0

,[H

þ

] ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

10

13:0

p

¼

10

6.5

mol dm

3

).

0011To measure pH values, So

¨

rensen used the electro-

chemical cell:

Pt, H

2

ðgÞjSolution X jSalt bridge jHg

2

Cl

2

jHg:

This representation indicates a hydrogen electrode

(hydrogen gas passed over a platinum metal elec-

trode) in a solution X and a calomel electrode (metal-

lic mercury in contact with calomel (Hg

2

Cl

2

), in

contact with a chloride ion solution) separated by a

salt bridge (which allows ionic conduction to occur,

but prevents solution X and the chloride ion solution

from mixing). For such a cell, the difference in electro-

motive force (emf) (E

1

E

2

) between two cells in

terms of the H

þ

ion concentrations [H

þ

]

1

and [H

þ

]

2

of the two solutions is given by the equation

E

1

E

2

¼ðRT=FÞlog

e

ð½H

þ

2

=½H

þ

1

Þ, ð4Þ

where R is the gas constant, T the temperature, and F

the Faraday constant. If [H

þ

]

2

is 1 mol dm

3

, E

2

will

have a definite value, E

0

. Therefore, E

1

E

0

¼(RT/

F)log

e

ð1=½H

þ

1

Þ,orE

1

¼ E

0

þ (RT log

e

10=FÞ p

s

H

1

¼

E

0

þ 0.05916 p

s

H

1

V (at 25

C) (p

s

H is used here

for So

¨

rensen’s pH). So

¨

rensen assumed that H

þ

1

¼

a

1

M

1

where a

1

is the degree of dissociation of the acid

in solution 1, and M

1

is its molality. E

0

¼ 0.3376 V at

18

C.

0012After this initial work of So

¨

rensen, it was realized

that the emfs of cells depend on activity rather than

concentration, and other assumptions were incorrect.

So

¨

rensen and Linderstro

¨

m-Lang (1924) proposed

p

a

H ¼log

10

a

H

þ

¼log

10

H

þ

y

H

þ

, where a

H

þ

is

the activity, [H

þ

] is the concentration of the H

þ

ion

in mol dm

3

, and y

H

þ

is the activity coefficient of the

H

þ

ion on the molarity scale. (To be strictly correct, a

ratio of concentrations, as earlier, is needed here to

give a dimensionless quantity.) These p

a

H values can

be shown to be related to the original p

s

H values by

the relationship:

4502 PH – PRINCIPLES AND MEASUREMENT

p

a

H ¼ p

s

H þ 0 :04 :ð5 Þ

Operational Definition of pH

0013 In the previous section, some of the problems of the

theory of pH were discussed. Careful study has

shown that the numbers obtained depend, in a com-

plex manner, on H

þ

ion activity of electrolytes in

solution, and it became clear than an operational

definition of pH and a standard scale were needed

to unify the great variety of pH measurements being

made by research scientists and by industry and com-

merce. Hence, we now have an operational definition

that has been endorsed by the International Union of

Pure and Applied Chemistry. This definition is

pH ðXÞ¼pH ðSÞþðE

S

E

X

ÞF =RTlog

e

10, ð6 Þ

where E

x

is the emf of the galvanic cell.

Reference electrode jKCl solution jSolution X

jH

2

ðgÞ,Pt

and E

s

is the emf of the same cell with solution X of

unknown pH(X) replaced by solution S of standard

pH(S).

001 4 In practice, a glass electrode is almost always used

in place of the platinum/hydrogen gas electrode. The

reference electrode is usually mercury/mercury(I)

chloride (calomel), silver/silver chloride, or thallium

amalgam/thallium(I) chloride. The standard reference

pH is that of an aqueous solution of potassium

hydrogen-phthalate of molality 0.05mol kg

1

at

25

C. This has a pH of 4.005.

Food and pH

0015 There are many instances when the food scientist

needs to measure or control pH. For example, pH

control is vital in the clarification and stabilization

of fruit and vegetable juices, in the use and control of

enzymes and microorganisms, in the preparation

of foods by the fermentation of fruit or cereals, in

the control of the texture of jams and jellies, and in the

stability of the color and flavor of fruits.

001 6 The properties (e.g., emulsification and foaming

ability) of many colloidal systems are affected by pH

– these include proteins, pectins, and gums, all of

which occur in foods. Chemical reactions that can

occur in foods, particularly hydrolysis, are catalyzed

by hydrogen ions, and therefore can be controlled by

controlling the pH of the system. (See Colloids and

Emulsions.)

001 7 Hydrogen ions affect the rate of growth of molds,

yeasts, and, particularly, bacteria. Usually, there is a

pH value at which optimum growth occurs, above

and below which growth is inhibited. The relation-

ship of pH to sterilization by heat is of particular

significance during the canning of foodstuffs. (See

Canning: Principles; Spoilage: Bacterial Spoilage;

Molds in Spoilage; Yeasts in Spoilage.)

0018pH is a rough measure of the maturity of fruit.

Young fruits initially have a pH close to that of

the plant, but this rapidly decreases as the acidity

increases. The pH of acidic fruits such as lemons

and limes is about 2.0, and that of mildly acidic fruits

about 4.0. These values can be compared with vege-

tables, which have pH values of 5–6. The pH ranges

of a number of fruits and other foods is listed in

Table 1.(See Ripening of Fruit.)

Buffer Solutions

0019Buffer solutions are of prime importance in pH deter-

minations, as they are the standards for both colori-

metric and electrochemical methods of determining

pH.

0020Buffer solutions are solutions that resist a change in

H

þ

ion concentration (pH) when an acid or alkali is

added to them. They are made up of a weak acid or

weak base and its salt.

0021The equilibria in a solution of, say, a weak acid and

its sodium salt are shown in eqns (7) and (8):

tbl0001Table 1 pH values of some foods

Food pH

Limes 1.8–2.0

Lemons 2.2–2.4

Gooseberries 2.8–3.0

Plums 2.8–3.0

Pickles 3.0–3.4

Grapefruit 3.0–3.4

Oranges 3.0–4.0

Rhubarb 3.1–3.2

Cherries 3.2–4.0

Pineapples 3.4–3.7

Pears 3.6–4.0

Apricots 3.6–4.0

Tomatoes 4.0–4.4

Bananas 4.5–4.7

Cheese 4.8–6.4

Carrots 4.9–5.3

Spinach 5.1–5.7

Potatoes 5.6–6.0

Peas 5.8–6.4

Tuna 5.9–6.1

Corn 6.0–6.5

Salmon 6.1–6.3

Butter 6.1–6.4

Chicken 6.2–6.4

Drinking water 6.5–8.0

PH – PRINCIPLES AND MEASUREMENT 4503

HA Ð H

þ

þ A

ð7Þ

NaA Ð Na

þ

þ A

:ð8Þ

As HA is a weak acid, equilibrium (eqn (7)) at

moderate concentration will lie over to the left, i.e.,

as undissociated acid HA. The equilibrium of the

sodium salt (eqn (8)) is a source of A

ions. If acid

(i.e., H

þ

ions) is added to this weak acid and salt

solution, the H

þ

ions will be removed as they will

combine with the A

ions to form undissociated HA.

If base (i.e., OH

ions) is added, the OH

ions will be

removed as they will combine with the H

þ

ions to

form water and the equilibrium (eqn (7)) will move to

the right to supply the H

þ

ions required. Hence, the

concentration of H

þ

ions in the solution (i.e., the pH)

will not change significantly. This is the buffer effect.

0022 Common buffer solutions are made from potas-

sium hydrogenphthalate with hydrochloric acid

or sodium hydroxide (for pH 3–5), potassium

dihydrogenphosphate with sodium hydroxide (for

pH 6–8), and boric acid with sodium hydroxide

(for pH 8–10).

0023 Biologically, the buffer effect is often more import-

ant than the absolute value of pH. For example,

buffer chemicals affect the way in which enzymes

and microorganisms respond when the pH is

changed. Juices from plant tissue have the ability to

buffer pH changes to a greater or lesser degree, owing

to the presence of organic acids, acid–salt systems,

proteins, and acid phosphates.

Measurement of pH

Colorimetric Methods

002 4 Determination of pH using the color of acid–base

indicators is a very simple technique that can be

carried out rapidly and reproducibly. Approximate

pH values can be obtained very quickly using pH

papers. Under optimum conditions, accurate values

of pH can be obtained by colorimetric methods. No

doubt, these methods will be used for many years to

come, but must become less favored with the advent

of portable, cheap, easy-to-use electrochemical pH

meters. (See Spectroscopy: Visible Spectroscopy and

Colorimetry.)

0025 Color change of acid–base indicators Indicators are

natural or artificial dyestuffs that are weak acids or

bases (acids and bases that are only partially dissoci-

ated) and have different colors in their acidic and

basic forms.

0026 If the indicator is written as HIn and it dissociates

(eqn (9))

HIn Ð H

þ

þ In

, ð9Þ

the equilibrium (or ionization) constant is

K

In

¼½H

þ

½In

=½HIn ;ð10Þ

and

½H

þ

¼K

In

ð½HIn =½In

Þ:ð11Þ

Using pH ¼log

10

[H

þ

],

pH ¼ pK

In

þ log

10

ð½In

=½HInÞ; ð12Þ

pK

In

is log

10

K

In

and is called the indicator con-

stant. The ratio [In

]/[HIn] determines the color of

the indicator in the solution, and eqn (12), therefore,

directly relates the color to the pH of the solution.

0027Eqn (12) shows that when pH ¼ pK

In

, the concen-

tration of the indicator in each form is equal (i.e.,

½HIn¼½In

), and that at all pH values, both

the acid (HIn) and basic (In

) forms of the indicator

are present in the solution. Our eyes are unable

to detect the color of less than about 10% of one

form of the indicator in the presence of the other,

and the solution will appear to be the ‘acid’ color

when [In

] / [HIn] < 1/10, and the ‘alkaline’ color

when [In

] / [HIn] > 10. Therefore, the solution will

be the color of the acid form of the indicator until

pH ¼ pK

In

1, when the color will appear to change

until it is that of the alkaline form of the indicator

from pH ¼ pK

In

þ 1. That is, the color changes over

approximately 2 in terms of pH. In practice, the range

for the color change is about 1.6–2 in terms of pH;

this corresponds to a 40–100-fold change in the H

þ

ion concentration. By choosing indicators with ap-

propriate pK

In

values, the whole of the pH range

may be covered – a selection of some common pH

indicators is given in Table 2.

0028Colorimetric Measurements of pH

Indicator papers For approximate determination of

pH values, indicator papers may be used. Of

particular value are ‘nonbleeding’ indicator papers.

These contain dyestuffs strongly bound to the cellu-

lose, so that the dye does not bleed into the test

solution. These indicator papers are available,

covering very narrow pH ranges, enabling moder-

ately accurate pH values to be obtained very cheaply,

conveniently, and quickly.

0029Comparison method This is carried out by adding

similar quantities of an indicator to the test solution

and a reference solution, and if the two solutions have

the same color, they are assumed to have the same

pH. The accuracy of the method, therefore, depends

on the accuracy of the pH of the reference solution.

4504 PH – PRINCIPLES AND MEASUREMENT