Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

parameters associated to the Casimir operators for

the Lie groups G

2

and R

7

. When interactions between

three electrons (for 4f

N

with NX3) are taken into

account, the Judd parameters T

k

are associated to

the t

k

operators, also transforming as the irreducible

representations of the G

2

and R

7

groups.

1.3 Spin–Orbit Coupling

The most important magnetic interaction is the cou-

pling between the spin and the orbit of an electron.

The radial part of the interaction defines the phen-

omenological spin orbit parameter, z:

H

SO

¼ z

N

X

N

i¼1

l

-

i

s

-

i

This interaction is not diagonal in L and S and con-

sequently the L–S coupling is broken and replaced by

the intermediate coupling. The matrix element is

written as:

/aSLJM7H

SO

7a

0

S

0

L

0

J

0

M

0

S ¼ dðJ; J

0

ÞdðM; M

0

Þ

½lðl þ 1Þð2l þ 1Þ

1=2

z

Nl

ð1Þ

LþS

0

þJ

LL

0

1

SS

0

J

()

/aSL7V

11

7a

0

S

0

L

0

S ð2Þ

in which l is the orbital quantum number (l ¼2 for 3d

elements and l ¼3 for 4f elements), V

11

is a double

tensor whose doubly reduced values are tabulated by

Nielson and Koster (1964), and {} represents the 6j

symbol for the coupling between three angular mo-

ments. The triangular rules of the 6j symbols are that

L and S cannot differ by more than one unit. In

group theory that interaction is associated to the

explicitly direct product D

S

#D

L

¼

P

J¼LþS

J¼7LS7

D

J

.

That interaction creates the

2S þ1

L

J

levels associated

with the D

J

irreducible representation, whose re-

maining degeneracy is 2J þ1. The energy separation

between two terms is about 500 cm

1

for the rare

earths whereas the coupling constant varies from

B700 cm

1

for Ce

3 þ

to B3000 cm

1

for Yb

3 þ

(from

B200 to B800 cm

1

for 3d elements).

1.4 Other Interactions

Other interactions of minor importance can be in-

cluded. They have essentially a magnetic origin just

like the spin–orbit coupling:

(i) the spin–other–orbit and spin–spin interac-

tions, parameterized by the Marvin integrals M

k

(k ¼0, 2, 4);

(ii) the electrostatically correlated spin–orbit inter-

action, parameterized by two-body pseudomagnetic

operators P

k

(k ¼2, 4, 6).

These interactions are considered practically for

the nf

N

configurations only when the number of ex-

perimental levels is large. They have a significant ac-

tion on the 4f

2

and 5f

2

configurations and on those at

the end of the series. Usually only M

0

and P

2

vary

freely, while the other parameters keep the Hartree–

Fock ratios with M

0

and P

2

.

2. Crystal Field Interaction

When embedded in a crystalline matrix the rare earth

ion is submitted to an internal electric field due to the

ligands, assimilated to point charges in the first ap-

proximation. Thus, in the original conception, the

crystal field has a purely electrostatic origin (Garcia

and Faucher 1995, Go

¨

rller-Wallrand and Binnemans

1996).This is the point charge electrostatic model

(PCEM). For one ligand the potential is written as:

V ¼

1

4pe

0

ge

7r r7

The potential is developed in Legendre polynomials

V ¼

ge

4pe

0

X

N

k¼0

r

k

r

kþ1

P

k

ðcosOÞð3Þ

then in spherical harmonics:

P

k

ðcosOÞ¼

4p

2k þ 1

X

q¼k

q¼k

Y

k

q

ða; bÞY

k

q

ðy; fÞð4Þ

The hamiltonian of the systems sums over all ligands

and electrons involved

H

c

¼e

X

i

Vðr

i

; y

i

; f

i

Þð5Þ

in Eqns. (3) and (4), the ligand and electron parts are

separated

H

c

¼

e

2

4pe

0

X

i;k;q

A

k

q

r

k

i

Y

k

q

ðy

i

; f

i

Þð6Þ

Table 2

Order of magnitude of the main interactions in the nl

N

configurations (cm

1

).

Configuration

Coulomb

rep. F

2

Spin–Orbit

z

Crystal

field B

k

q

3d

N

70 000 500 15 000

4d

N

50 000 1000 20 000

5d

N

20 000 2000 25 000

4f

N

70 000 1500 500

5f

N

50 000 2500 2000

150

Electronic Configurations of 3d,4f,and5f Elements: Properties and Simulation

with

A

k

q

¼

4p

2k þ 1

X

j

g

j

r

kþ1

j

Y

k

q

ða

j

; b

j

Þð7Þ

where A

k

q

is the lattice sum depending on the spher-

ical coordinates of the ligands and g

j

is the electric

charge of the jth ligand. Using perturbation theory,

the energy is written as:

E

ð1Þ

cc

¼ /F

ð0Þ

7H

c

7F

ð0Þ

S ð8Þ

F

ð0Þ

being the nonperturbed state, and in that ex-

pression appear the radial integrals /R

4f

7r

k

7R

4f

S ¼

/r

k

S. These integrals can be obtained directly from

the routine package of Cowan. The crystal field pa-

rameters are defined as the product of an angular part

by a radial part: B

k

q

¼ A

k

q

/r

k

S.

2.1 Limitations of the Crystal Field Potential

Equation (3) indicates a summation over k, an integer

without any limitation and in Eqn. (4) a summation

over q, also integer. In fact, the physical application

to electronic configurations and the group theory

rules reduce the possible values:

(i) there is a limitation on k due to the nature of

the electrons. If the crystal field potential operates as

in Eqn. (8) between states of to the same configura-

tion (which is the case for most of the crystal field

analysis), then k is even and kp2l;

(ii) there is also a limitation on q connected to the

symmetry of the point group, for instance:

(a) if there is an inversion center in the group

symmetry like O

h

,S

6

, all odd B

k

q

vanish;

(b) if there is a C

n

or S

n

symmetry axis, q/n must

be an integer;

(c) other rules are less evident but are a conse-

quence of the application of the projection operators

associated with the point group on the spherical har-

monics.

An exhaustive list of nonvanishing B

k

q

vs. point

symmetries is found in the work of Go

¨

rller-Wallrand

and Binnemans (1996).

2.2 Group Theory and Crystal Field

From the group theory point of view the irreducible

representations G

x

of the point group G, associated

with the atomic position occupied by the rare earth

ligands are considered. G is a subgroup of the rota-

tion group R

3i

for an even number of electrons and of

the rotation double group R

3i

0

for an odd number of

electrons. The number and the type of irreducible

representations of the subgroup G involved are

determined by decomposition of the D

J

irreducible

representation of R

3i

(or R

3i

0

) on the basis of the

G symmetry operations. The list of the J level

decomposition as a function of the J value and of

point groups is found in Go

¨

rller-Wallrand and Binne-

mans (1996) or Prather (1961).

2.3 Crystal Field Strength

It is often interesting to classify the compounds as a

function of the crystal field strength. This parameter

can cover the whole crystal field effect or partial ef-

fect as a function of the rank k of the parameters.

This quantity is a rotational invariant, connected

with the displacements of the centers of gravity of the

levels from their free ion values. It allows a simple

characterization of chemical bondings. It is written as

(Chang et al. 1982):

S ¼

X

k¼2;4;6

1

2k þ 1

X

q¼k

q¼k

7B

k

q

7

2

"#

1=2

2.4 The Racah Algebra Formalism of the

Crystal Field

Equation (3) supposes that the crystal field potential

has a pure electrostatic origin. Except for cases in-

volving ionic ligands, this model is unable to repre-

sent the reality. For a quantum mechanical treatment

it is more realistic to keep only the symmetry aspect

of the mathematical expression. The crystal field

hamiltonian is then written as:

H

c

¼

X

i;k;q

B

k

q

½C

k

q

þð1Þ

q

C

k

q

i

þ iS

k

q

½C

k

q

ð1Þ

q

C

k

q

i

ð9Þ

The summation runs over all electrons of the system,

where B

k

q

and S

k

q

are the real and imaginary parts,

respectively, of the phenomenological crystal field

parameters and C

k

q

are tensor operators of rank k,

connected to the spherical harmonics. The Wigner–

Eckart theorem gives a simple expression of the cou-

pling between two angular momentums in the

7ZSLJMS basis:

/aSLJM B

k

q

C

k

q

a

0

S

0

L

0

J

0

M

0

S ¼ dðS; S

0

Þð1Þ

l

ð2l þ 1Þ

l k l

000

!

ð1Þ

JM

JkJ

0

MqM

0

!

B

k

q

/aSLJ8U

k

8aSL

0

J

0

S ð10Þ

where () are 3j symbols for two angular moment

couplings. The second 3j symbol shows the possi-

bilities of coupling between states of different J

(J-mixing), which can never be neglected. U

k

is a

unitary tensor. Equation (10) can be developed

151

Electronic Configurations of 3d,4f, and 5f Elements: Properties and Simulation

further:

/aSLJ8U

k

8aSL

0

J

0

S ¼ð1Þ

SþL

0

þJþk

ð2J þ 1Þð2J

0

þ 1Þ½

1=2

J

0

Jk

L

0

LS

()

/aSL8U

k

8aSL

0

S ð11Þ

in which /aSL8U

k

8aSL

0

S is a doubly reduced ma-

trix element also tabulated by Nielson and Koster.

The order of magnitude of the crystal field splitting is

shown in Table 2.

2.5 Correlated Crystal Field

The concept of correlated crystal field corresponds to

the two-electron part of the crystal field interaction.

This interaction was formalized in the 1970s and im-

plies a ‘‘scandalously high number of parameters’’

(Garcia and Faucher 1995). That interaction creates a

term-dependent correction to the one-electron crystal

field. It has been somewhat ‘‘simplified’’ by consi-

dering separately the spin- and orbital-correlated

crystal field effects. Thus, the operators become or-

thogonal to the one-electron crystal field operators

and are easier to manipulate. However, it has not

been shown clearly if the simulation of the energy

level scheme is significantly improved when these

interactions are included. A clever overview on that

problem is found in the work of Garcia and Faucher

(1995).

3. Simulation o f the Rar e Earth Electronic

Configurations

When all interactions are analyzed and described it is

easy to write down the secular determinant. It com-

prises a great number of matrix elements, written as

/aSLJM7H

Tot

7a

0

S

0

L

0

J

0

M

0

S in which H

Tot

represents

the sum of elementary hamiltonians previously des-

cribed:

H

Tot

¼H

0

þ

X

k¼0;1;2;3

E

k

e

k

þ

4f

A

SO

þ LðL þ 1Þ

þ GðG

2

ÞþGðR

7

Þþ

X

k¼2;4;6

P

k

p

k

þ

X

k¼0;2;4

M

k

m

k

X

k¼2;3;4;6;7;8

T

k

t

k

þ

X

k;q;i

B

k

q

C

k

q

ðiÞ

ð12Þ

Each interaction follows its own rules, in particular

as regards its nonzero values as a function of the

quantum numbers ZSLJM. H

0

represents the energy

separation between the ground and excited con-

figurations. The diagonalization done by standard

techniques provides the energy levels and their

associated wave-functions. An estimation of the

phenomenological parameters is made by comparing

calculated and experimental energy levels by minimi-

zation of the root mean square deviation taken as

factor of merit (Porcher 1989, unpublished Fortran

routines). For the rare earths the number of free ion

parameters match 20 and the number of crystal field

parameters can vary between two (for O

h

or T

d

point

symmetry) and 27 (for C

1

). This last number could be

largely increased if the two-electron crystal field effect

is included. Thus, it is very common to take into ac-

count some 20 parameters, which creates a problem

concerning the real significance of the parameters and

the reliability of the phenomenological simulation.

Fortunately, various models help in calculating

many parameters whose values are considered as

starting values in the refining processes. This is true

for the free ion parameters as well as for the crystal

field parameters (see Sect. 4).

*

Free ion parameters calculated by the Hartree–

Fock method (Cowan) reproduce the reality with a

precision of B25%, which is reasonable.

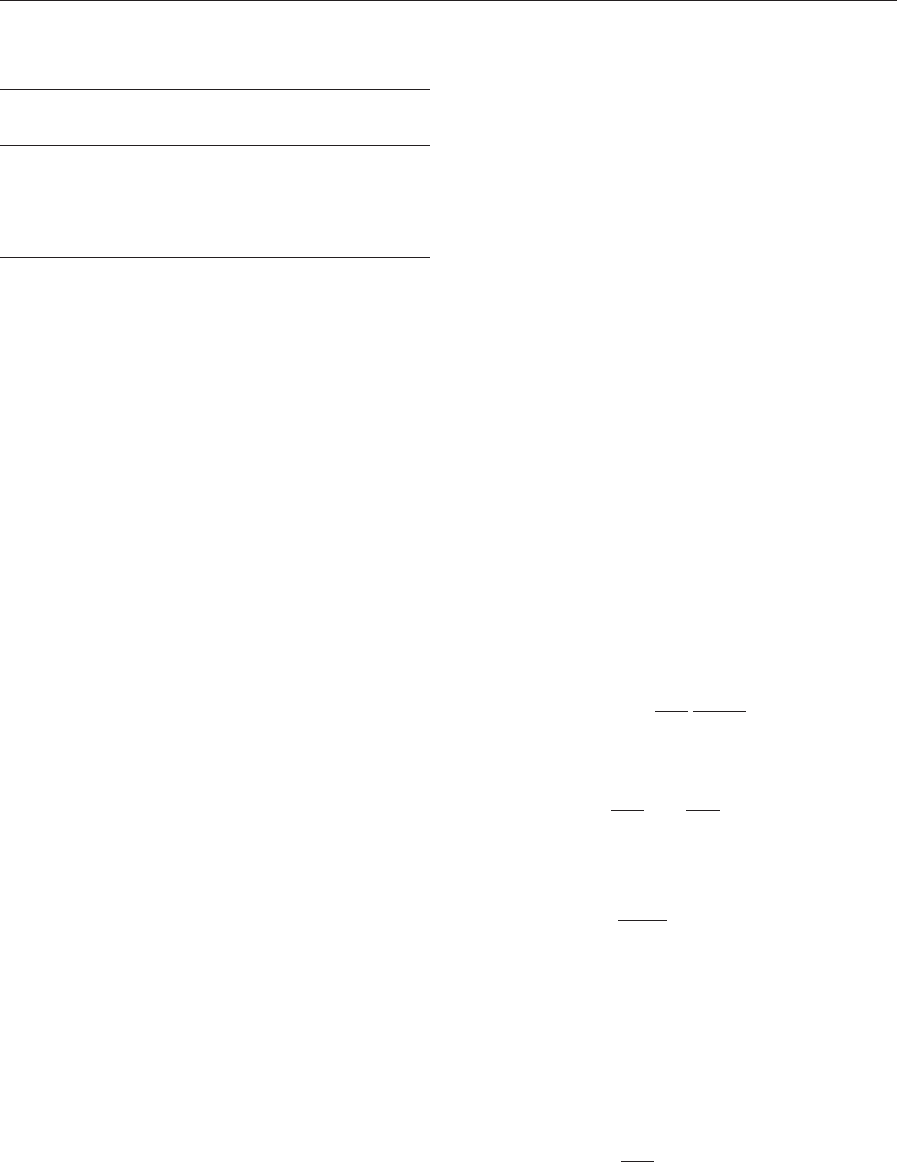

*

There is a smooth variation of free ion param-

eters vs. the number of f electrons, whatever the

crystalline matrix (Fig. 2).

*

If all free ion parameters cannot vary freely,

some of them are fixed in predetermined ratios. This

is often the case for the M

k

and P

k

integrals and

sometimes for the E

k

(or F

k

) parameters.

*

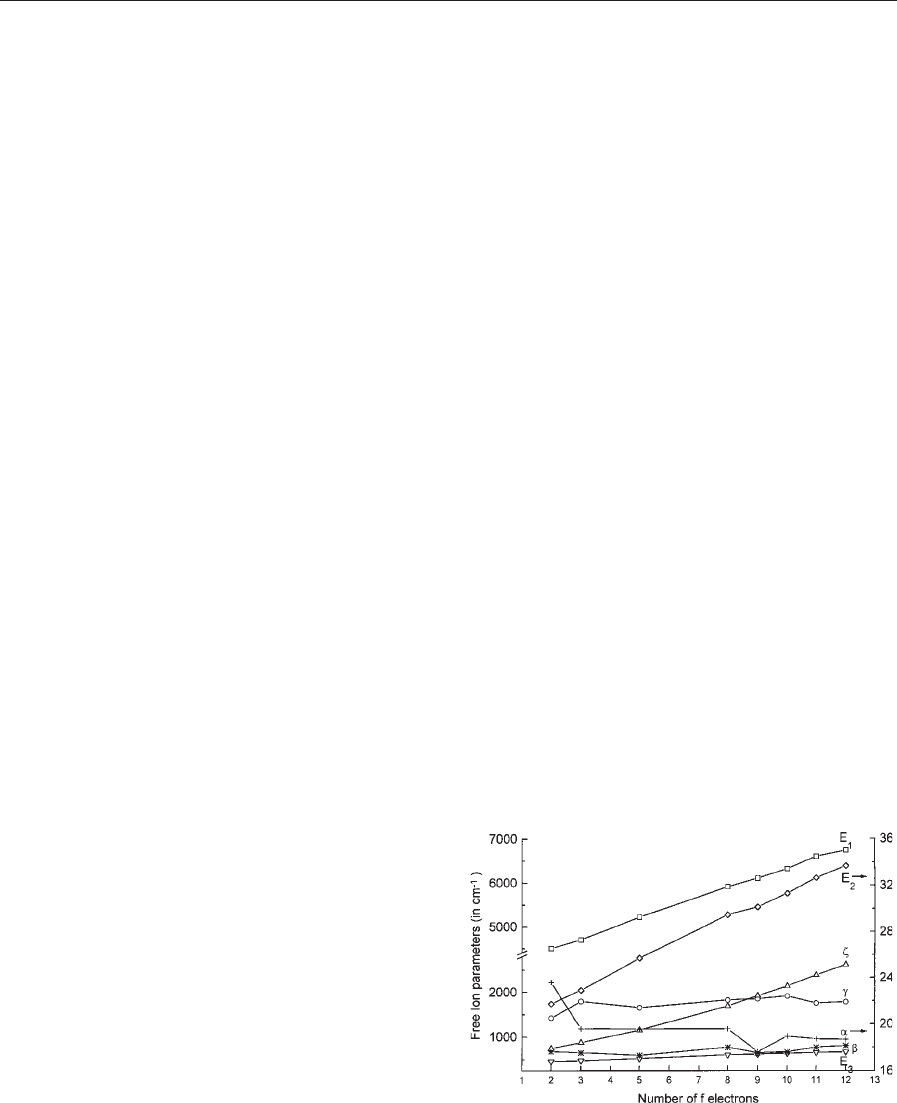

There is also a smooth variation of the crystal

field parameters with the ionic radius of the optically

active rare earth embedded in a given matrix or when

the crystalline matrices are isostructural (Fig. 3).

*

In some cases, a descending symmetry proce-

dure is applied for crystal field calculations, assuming

the real point symmetry is close to a higher one in-

volving less parameters.

In spite of the relative simplicity of these calcula-

tions, few works deal with the optical properties of all

rare earth ions in a unique matrix, in single crystal

Figure 2

Variation of the free ion parameters in the REOCl

series. From Ho

¨

lsa

¨

et al. (1998a), reprinted with the

permission of the authors.

152

Electronic Configurations of 3d,4f,and5f Elements: Properties and Simulation

form. The most complete work was published by

Carnall as early as 1977 for pure rare earth fluoride

REF

3

or rare earth doping in lanthanum fluoride

LaF

3

. This particular matrix is transparent in the far-

UV region and therefore gives a great number of ex-

perimental energy levels. Initially the simulations

were performed with approximated symmetries for

the lanthanum (D

3h

then C

2v

), the last revision con-

sidering the real symmetry (C

2

). Later, two other

families were systematically studied,but in polycrys-

talline form, with all trivalent rare earth ions: the rare

earth oxychlorides REOCl (Ho

¨

lsa

¨

et al. 1998a) and

the oxyfluorides REOF (Ho

¨

lsa

¨

et al. 1998b), where

the rare earth occupies a point site with higher sym-

metry—C

4v

for REOCl and C

3v

for REOF respec-

tively—which means less crystal field parameters (five

and six, respectively). The number of observed energy

levels is large and SmOF could be added to the

Guiness Book of Records for rare earth spectroscopy

with 191 observed crystal field states! Many other

matrices have been studied, not necessary with all

rare earth ions, especially with Nd

3 þ

,Eu

3 þ

, and

Er

3 þ

which are ions with potential industrial appli-

cation. Most of the results concerning rare earth

energy levels are available in books (Go

¨

rler-Wallrand

and Binnemans 1996, Kaminski 1996) and/or on web

sites (NASA, Porcher 2000).

4. Semiempirical Calculation of the Crystal

Field Parameters

Newmann (1971) noted that several different inter-

actions should have to be taken into account: ligand

point charges of first neighbors and of the rest of the

crystalline network, dipolar and quadrulopar polar-

ization of the ligand, exchange and overlap between

the rare earth and the ligand, covalency, charge

transfer ligand-to-rare earth and ligand-to-ligand,

and triangular interaction. He was able to calculate

the different contributions for PrCl

3

, i.e., in the case

of a relatively simple ligand. Others have estimated

the influence of the polarizability for some simple

covalent ligands (Garcia and Faucher 1995, Morrison

and Leavitt 1982). The problem is more complicated

when complex ligands, such as borates, molybdates,

and sulfates, are involved. Increasing difficulties are

presented by organic ligands. For these reasons it

seems more realistic to consider semi-empirical cal-

culations. A review of the different models is given by

Porcher et al. (1999).

4.1 Angular Overlap Model

This model is an extension to the f electrons of the

model proposed by Jrgensen (1963) and Scha

¨

ffer

(1969, 1972) for the d electrons. It was initially in-

troduced for explaining the one-electron energy dif-

ferences between the seven 4f orbitals in lanthanide

chromophores, and forms the most ‘‘chemical’’ ap-

proach in the sense that the f orbitals are immediately

considered. The model expresses the antibonding en-

ergy of the molecular orbital created between the

central ion and the ligand. One interest of this model

is to consider f orbital expressions directly as read on

the character table of the point symmetry group,

which allows the result to be related to the irreducible

representation of a level and consequently to the s, p,

and d classical bonding of the d elements plus the f

bonding specific to the f orbitals. However, difficul-

ties arise when the phenomenological approach of

a4f

N

configuration simulation is considered as a

whole, which also includes the free ion interac-

tions. This model has been applied, coupled with

the superposition model in various series of rare earth

compounds.

4.2 Superposition Model

Newmann (1971) proposed an empirical approach,

where each ligand is characterized by an intrinsic pa-

rameter, giving its own contribution to the crystal

field. The general expression of B

k

q

is:

B

k

q

¼ /r

k

S

4p

2k þ 1

X

j

Y

k

q

ðjÞ

%

A

k

ðR

j

Þ

R

0

R

j

t

k

ð13Þ

In that expression only the first coordination

sphere is considered. There is a distance dependence

of B

k

q

according to a power law, the rare earth–ligand

distance reference R

0

being the shortest in the crys-

talline network. This semi-a priori model is strictly

identified with the PCEM if t

k

is equal to 2k þ1. t

k

could be calculated according to the number and the

type of considered interactions. Practically they are

considered as adjustable parameters, whose values

Figure 3

Variation of the crystal field parameters in the REOCl

series. From Ho

¨

lsa

¨

et al. (1998a), reprinted with the

permission of the authors.

153

Electronic Configurations of 3d,4f, and 5f Elements: Properties and Simulation

are not necessarily integers and can be far from the

nominal ones. The interest of that model lies in the

fact that each ligand gives its quantitative finger-print

which in principle could be transported from one

compound to another.

4.3 Effective Charge Model

In this model, the crystal field parameters are writ-

ten as:

B

k

q

¼ð1 s

k

Þ

/r

k

S

t

k

A

k

q

ð14Þ

This equation differs in four ways from the PCEM

of Eqns. (4) and (5) in the expression of the radial as

well as in the angular parts.

(i) The radial integrals /r

k

S are corrected by a

spatial expansion parameter t, which varies linearly

with the number of f electrons.

(ii) A shielding factor s

k

is introduced into the

multipolar expansion of the crystal field potential.

(iii) A degree of covalence is introduced through

effective charges of atoms. These effective charges

keep the electric neutrality of the compound.

(iv) A slight shift of the ligand position is intro-

duced in order to take into account their polarizabil-

ity effect.

The summation runs over all atoms of the crystal-

line network, which in practice means atoms included

within a sphere of ca. 100 A

˚

.

4.4 The Simple Overlap Model

This model developed by Malta retains only the first

coordination sphere (Porcher et al. 1999). The cova-

lence is represented by the overlap, r, between the

rare earth and ligand orbitals. The crystal field pa-

rameters are written as:

B

k

q

¼ r

2

17r

kþ1

/r

k

SA

k

q

ð15Þ

In that expression the /r

k

S radial integral is not

corrected from the spatial expansion as for the ECM.

Lattice sums, A

k

q

, are calculated with an effective

charge for the ligand. The overlap r varies for each

ligand as a function of the distance to the central ion

and is referred to the closest ligand, as for the super-

position model. Finally, this method involves only

two adjustable parameters: the overlap and the ef-

fective charge of the ligand. The model which offers

the possibility of considering the big molecules of

coordination chemistry has been successfully applied

to a great number of compounds. It was found that

the overlap is between 0.05 and 0.08 for the rare earth

ions and between 0.10 and 0.25 for 3d elements.

5. The Convenient Case of the Eu

3 þ

Ion

Although the 4f

6

configuration possesses one of the

greatest degeneracy (3003) of the trivalent rare earth

configurations (Table 2), Eu

3 þ

is the most convenient

case for characterizing the energy levels of a rare

earth ion in a crystalline matrix. This characteristic is

due qualitatively to the type of symmetry site analysis

of the spectroscopy as well as quantitatively to the

relatively simple way of performing crystal field cal-

culations. To a lesser extent, this is also true for in-

tensity calculations. The particular feature of this

configuration is a

7

F ground septet and a first excited

5

D quintet relatively well isolated in the energy level

sequence.

5.1 Eu

3 þ

as a Structural Local Probe

This analytical aspect is a consequence of the even

number of electrons in the 4f

6

configuration. The

crystal field lifts more or less completely the degen-

eracies of

7

F

J

levels, according to the endomorphism

between crystal field levels and irreducible represen-

tations of the local point group, whereas the observ-

ability of electronic transitions is related to the

electric/magnetic dipole rules, also connected to the

point symmetry. Practically, a fluorescence spectrum

of europium compounds consists of transitions orig-

inating from the

5

D

J

levels, more particularly

5

D

0

, the

final levels being

7

F

J

. Most of the transitions are lo-

cated in the visible wavelength range. Neither

5

D

0

nor

7

F

0

are split by the crystal field, which means that the

number of

5

D

0

-

7

F

0

transitions corresponds to the

number of sites occupied by Eu

3 þ

. However, this is

only true if the group is due to the C

1

,C

s

,C

n

,C

nv

symmetry point groups, for which that transition is

permitted by the electric dipole rules. From the

number of observed lines and by application of the

same rules on other

5

D

0

-

7

F

J

(J ¼1,6) transitions,

the symmetry of the point group of the rare earth

crystallographic site in the structure is deduced. An-

other practical consequence is that liquid helium

temperature measurements are not necessary, where-

as it is required for other rare earth levels to prevent

the excited crystal field emitting levels being thermal-

ly populated. Thus, only liquid nitrogen measure-

ments are usually performed.

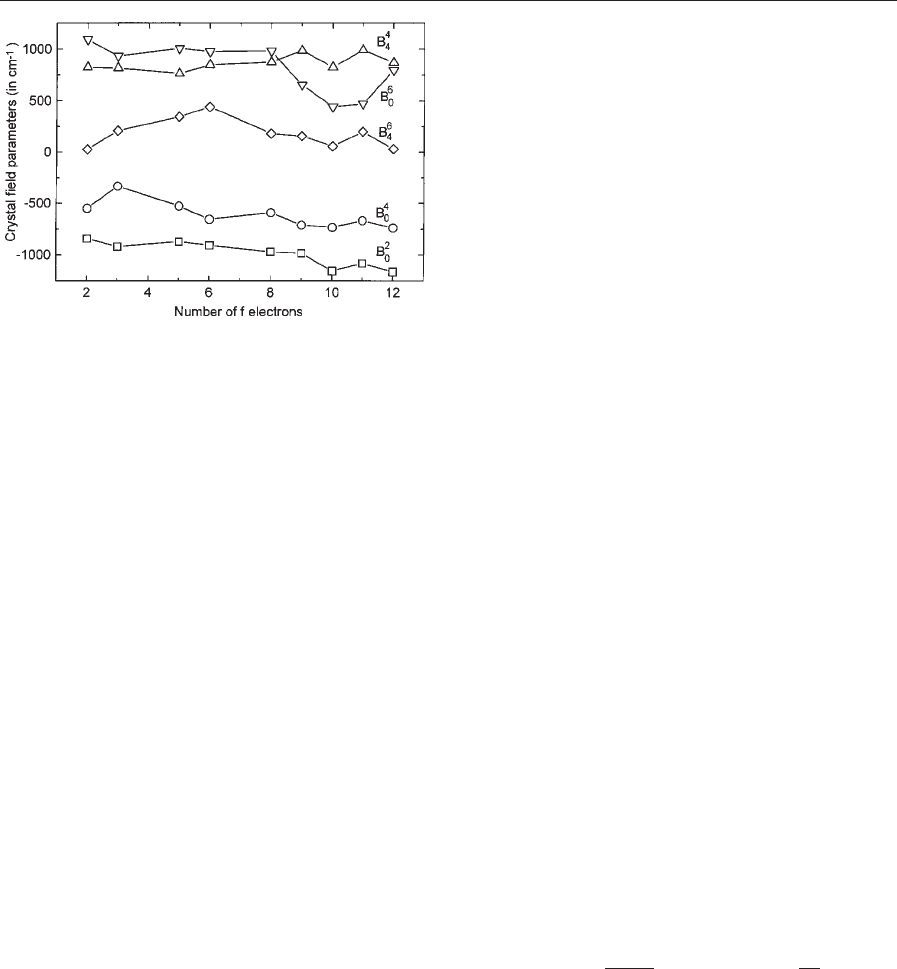

Moreover, the

5

D

0

-

7

F

0

transition is situated just

in the middle of the Rhodamine 6G dye laser wave-

length emission range. This low-cost dye can be used

for site-selective excitation in the case of multisite

compounds. When the excitation wavelength is ac-

corded on a selected

5

D

0

-

7

F

0

transition each site

gives its own ‘‘finger-print’’, any fluorescence re-

sponse from other sites being almost completely

quenched. Figure 4 shows, as an example, the case

of La

2

(CrO

4

)

3

.7H

2

O:Eu

3 þ

in which the rare earth

occupies two point sites of low symmetry. The

154

Electronic Configurations of 3d,4f,and5f Elements: Properties and Simulation

fluorescence spectrum excited by the blue lines of the

cw-Ar

þ

laser shows two lines for

5

D

0

-

7

F

0

(bottom

spectrum), whereas

5

D

0

-

7

F

1,2

transitions exhibit

more lines than expected for one point site. When

selectively excited (Fig. 4, middle and top spectra),

each site can be analyzed in terms of number and

position of lines and the problem is nicely reduced to

the case of a single site compound. If one of the sites

is due to an impure phase the same result should be

obtained. This structural probe aspect has been

found to be of great importance in biochemistry.

5.2 Crystal Field Calculations With Eu

3 þ

The particular

7

F ground septet is convenient for fast

crystal field calculation because: (i) this term is well

isolated from the rest of the configuration with an

energy gap of B12 000 cm

1

between

7

F

6

and

5

D

0

;

(ii) the crystal field operator is a spin operator which

allows mixing only between terms of the same parity;

(iii) the

7

F term only has this multiplicity; and (iv)

the

7

F term wavefunctions are almost pure (495%)

in 7

7

F

JM

S states, the rest being small admixtures

of

5

D,

5

G,

3

P,

3

F ,and

1

S terms created only by the

spin–orbit coupling. Instead, considering the entire

configuration even reduced in submatrices according

the crystalline quantum number properties, only a

49-square matrix (i.e., the

7

F degeneracy) is dia-

gonalized, which means less than half a second of

computation on a standard PC. In this case, the elec-

trostatic repulsion and other interactions operating

between terms are completely diagonal in 7

7

F

JM

S

states except for the spin–orbit coupling. Of course,

if a precise knowledge of the wave-functions is

necessary, as for paramagnetic susceptibilities and

for transition intensity calculations, the full secular

determinant has to be diagonalized (see Crystal Field

and Magnetic Properties, Relationship Between).

5.3 Intensity Calculations With Eu

3 þ

Although it is not the purpose of this article we can

mention how the europium ion permits an easier pa-

rameterization of the emission intensity, without the

usual experimental complexities of absolute measure-

ments. This is due to the simultaneous occurrence of

magnetic and electric dipole transitions in the spec-

trum. Some of the transitions between crystal field

states of

5

D

0

-

7

F

1

,

5

D

1

-

7

F

0

,

5

D

1

-

7

F

2

,

5

D

2

-

7

F

1

,

5

D

2

-

7

F

3

, etc., have a pure magnetic dipole charac-

ter. The problem is then reduced to the measurements

of relative intensities. However, a reference transition

for each emitting level is necessary in order to take

into account the nonradiative transition processes.

When transitions between J levels are studied, O

2

and

O

4

, respectively, are deduced directly from the area

ratios

5

D

0

-

7

F

2

5

D

0

-

7

F

1

and

5

D

0

-

7

F

4

5

D

0

-

7

F

1

See also: Crystal Field Effects in Intermetallic

Compounds: Inelastic Neutron Scattering Results;

Localized 4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism

Bibliography

Antic-Fidancev E, Lemaıˆ tre-Blaise M, Porcher P, Bueno I,

Parada C, Saez-Puche C 1991 Optical and magnetic proper-

ties of europium-doped potassium rare earth double chro-

mate. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 182, 5–8

Carnall W T, Goodman G L, Rajnak K, Rana R S 1989 A

systematic analysis of the spectra of the lanthanides doped

into single crystal LaF

3

. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 3443–57

Chang N C, Gruber J B, Leavitt R P, Morrison C A 1982

Optical spectra, energy levels and crystal field analysis of

tripositive rare earth ions in yttrium oxide. J. Chem. Phys. 76,

3877–89

Cowan R D, Fortran Routines for Atomic Spectroscopy. ftp://

aphysics.lanl.gov/pub/cowan/

Garcia D, Faucher M 1995 Crystal field in non-metallic (rare

earth) compounds. In: Gschneidner K A, Eyring L (eds.)

Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths.

Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 21

Go

¨

rller-Walrand C, Binnemans K 1996 Rationalization of

crystal-field parametrization. In: Gschneidner K A, Eyring L

(eds.) Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths.

Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 23

Ho

¨

lsa

¨

J, Lamminma

¨

ki R-J, Porcher P 1998a Simulation of

the energy levels of Dy

3 þ

in DyOCl. J. Alloys Compounds

275–277, 398–401

Figure 4

Site selective excitation on La

2

(CrO

4

)

3

.7H

2

O:Eu

3 þ

.

From Antic-Fidancev et al. (1991). Reprinted with the

permission of the authors.

155

Electronic Configurations of 3d,4f, and 5f Elements: Properties and Simulation

Ho

¨

lsa

¨

J, Sailyonoja E, Ylha

¨

P, Antic-Fidancev E, Lemaıˆ tre-

Blaise M, Porcher P, Deren P, Strek W 1998b Analysis and

simulation of the optical spectra of the stoichiometric NdOF.

J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 94, 481–7

Jrgensen C K 1963 Spectroscopy of transition group com-

plexes. Adv. Chem. Phys. 5, 33–146

Judd B R 1963 Operator Techniques in Atomic Spectroscopy.

McGraw Hill, New York [repr. 1998 Princeton University

Press, Princeton, NJ]

Kaminski A A 1996 Crystalline Lasers: Physical Processes and

Operating Systems. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

Morrison C A, Leavitt R P 1982 Spectroscopic properties of the

triply ionized lanthanides in transparent host crystals. In:

Gschneidner K A, Eyring L (eds.) Handbook on the Physics and

Chemistry of Rare Earths. North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 5

NASA Website: http://aesd.larc.nasa.gov/gl/laser/elevel/elevel.htm

Newman D J 1971 Theory in lanthanide crystal field. Adv. Phys.

20, 197–256

Nielson C W, Koster G F 1964 Spectroscopic Coefficients for

p

N

,d

N

and f

N

Configurations. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Porcher P 2000 Data base of experimental and calculated crys-

tal field energy levels in rare earths compounds. http://

www.enscp.jussieu.fr/labos/LCAES

Porcher P, Couto Dos Santos M, Malta O L 1999 Relationship

between phenomenological crystal field parameters and the

crystal structure: the simple overlap model. Phys. Chem.

Chem. Phys. 1, 397–405

Prather J L 1961 Atomic energy levels of rare earths. Mono-

graph 19, U.S. National Bureau of Standards, Washington

Scha

¨

ffer C E 1969 A perturbation representation of the weak

covalent bonding. Struct. Bondings 5, 68–95

Scha

¨

ffer C E 1972 Two symmetry parametrization of the an-

gular-overlap model of the ligand-field. Struct. Bondings 14,

69–109

Wybourne B G 1965 Spectroscopic Properties of Rare Earths.

Interscience, New York

P. Porcher

Laboratoire de Chimie Applique

´

e de l’Etat Solide

Paris, France

Elemental Rare Earths: Magnetic

Structure and Resistance, Correlation of

The study of elemental rare earths spans several dec-

ades, and in this period there have been many re-

ported studies of resistance and magnetoresistance.

The results reveal many magnetic transitions as a

function of temperature and applied field. However,

as stated in Boltzmann Equation and Scattering Mech-

anisms, there are no general rules that may be applied

for the magnetically ordered state, especially in the

case of antiferromagnetism. This fact derives from

the diversity of magnetic structures.

Electrical resistivity is a sensitive probe in magnetic

systems and the construction of magnetic phase

diagrams is possible. However, such constructions

based on magnetoresistance alone must be made with

caution, and this article will look at various aspects

which are important in such determinations. The ex-

tent of the field is enormous, and in consequence the

review will consider examples of heavy rare earths,

with the cases being chosen to exemplify the effects of

changing crystal field anisotropy and magnetic ex-

change interaction. Utilizing the results of elastic and

inelastic neutron scattering, it is possible to establish

canonical behavior in the resistance in response to

changing magnetic structure.

1. Magnetic Orde r in Rare-earth Elements

As with all physical systems, it is possible to define a

Hamiltonian. The spin Hamiltonian is composed of

terms intended to represent the possibility of strong

anisotropic behavior through crystal field and mag-

netic exchange. These terms are often linked to the

crystal lattice through magnetoelastic coupling. Con-

sideration of the spin Hamiltonian is beyond the scope

of the current article, and the reader is referred to

Jensen and Mackintosh (1991) and references therein.

The elements chosen for discussion are thulium

and erbium. The crystal structure for each of these

elements is hexagonal close-packed (h.c.p.), with the

three orthogonal symmetry directions being the a, b,

and c axes. The crystal field for each element is such

that the preferred orientation of the magnetic mo-

ments is along different directions. In the case of

thulium, the moment is constrained to the c-axis. In

erbium, the moments are found to develop first along

the c-axis, and then an additional moment develops

along the a-axis. In each case, the propagation wave

vector for the antiferromagnetic structures is parallel

to the c-axis. The RKKY-exchange energy (Jensen

and Mackintosh 1991) is found to increase going

from thulium to erbium. The main consequences of

this are an increase in the Ne

´

el temperature, and a

decrease in the role played by the crystal field within

the Hamiltonian.

1.1 Models Proposed to Understand Phenomena

In Boltzmann Equation and Scattering Mechanisms,

Eqn. (68a) introduces the Matthiessen rule for elec-

trical resistivity. For the systems considered in this

article, the rule may be restated (see Eqn. (9) in In-

termetallic Compounds: Electrical Resistivity) as:

r

total

¼ r

residual

þ r

phonon

þ r

magnetic

ð1Þ

where r

magnetic

is the component derived from the

elastic and inelastic magnetic scattering. This may be

represented by the equation:

r

magnetic

¼r

0

magnetic

Z

N

N

dð_oÞ

_o=k

B

T

4 sin h

2

ð_o=2k

B

TÞ

X

a

1

p

/w

00

aa

ðq; oÞS

q

ð2Þ

156

Elemental Rare Earths: Magnetic Structure and Resistance, Correlation of

where the weighted q-average of the susceptibility

tensor components is given by

/w

00

aa

ðq; oÞS

q

¼

3

ð2k

F

Þ

4

Z

2k

F

0

qdq

Z

dO

q

4p

ðq

#

uÞ

2

w

00

aa

ðq; oÞð3Þ

The term r

magnetic

may represent a number of dif-

ferent cases of excitations in the magnetic case, rang-

ing from spin-wave scattering (Mackintosh 1963),

crystal field (Hessel Andersen et al. 1974), and ex-

change dominated magnetic scattering (Hessel And-

ersen et al. 1980, Ellerby et al. 1998). In the high

temperature limit, Eqn. (2) predicts the saturation of

the spin-disorder scattering and is found to be pro-

portional to the de Gennes factor (see Intermetallic

Compounds: Electrical Resistivity).

In the heavy rare earths, measurement of the c-axis

resistivity reveals a pronounced increase at the Ne

´

el

temperature (Fig. 1). It was proposed (Mackintosh

1962) that this increase derives from a new periodicity

along the c-axis, associated with the magnetic unit

cell. This new periodicity results in additional zone

boundaries (superzones), and produces further ener-

gy gaps which may appear at the Fermi surface.

Watson et al. (1968) showed that, for the case of

thulium, there was a number of such gaps with an

energy of approximately 0.085 eV. Two groups (Elli-

ott and Wedgwood 1963, Miwa 1963) developed a

formalism to represent the effects of changing Fermi

surface on the resistivity, and this is summarized by:

r

uu

total

¼

r

uu

residual

þ r

uu

phonon

þ r

uu

magnetic

1 G

u

M

1

=M

0

1

ð4Þ

Here G

u

is determined by the periodicity of the

magnetic structure and for the ferromagnetic case,

where ordering wave vector Q ¼0 and G

u

¼0. M

0

1

and M

1

are the zero temperature saturation magnetic

moment and temperature-dependent magnetic mo-

ment, respectively, which may be derived from neu-

tron diffraction studies. The subscripts and

superscripts, uu and u represent the axis under con-

sideration. In the case of thulium, G

c

¼0.73 and

G

a

¼0 (Ellerby et al. 1998). The influence of the de-

nominator is to increase the resistivity parallel to the

c-axis as a function of temperature.

The magnetoresistance in magnetically ordered

materials has been considered by Yamada and

Takada (1973), and has been discussed in Magneto-

resistance: Magnetic and Nonmagnetic Intermetallics.

This model considers the effects, in an antiferromag-

netic system, of scattering from enhanced transverse

spin fluctuations resulting from an applied magnetic

field. The authors also produce a schematic for the

effect of spin-flop transitions on the resistivity, where

the moments do not fully rotate parallel to the

applied field in a single stage, but do so in a series of

stages. This model for the magnetoresistance does not

accommodate the affects of changing Fermi surface.

2. Discussion

The difference in anisotropy of thulium and erbium

has already been alluded to in Sect. 1. The discussion

begins in each section by outlining the main features

for each of the magnetic phase diagrams shown in

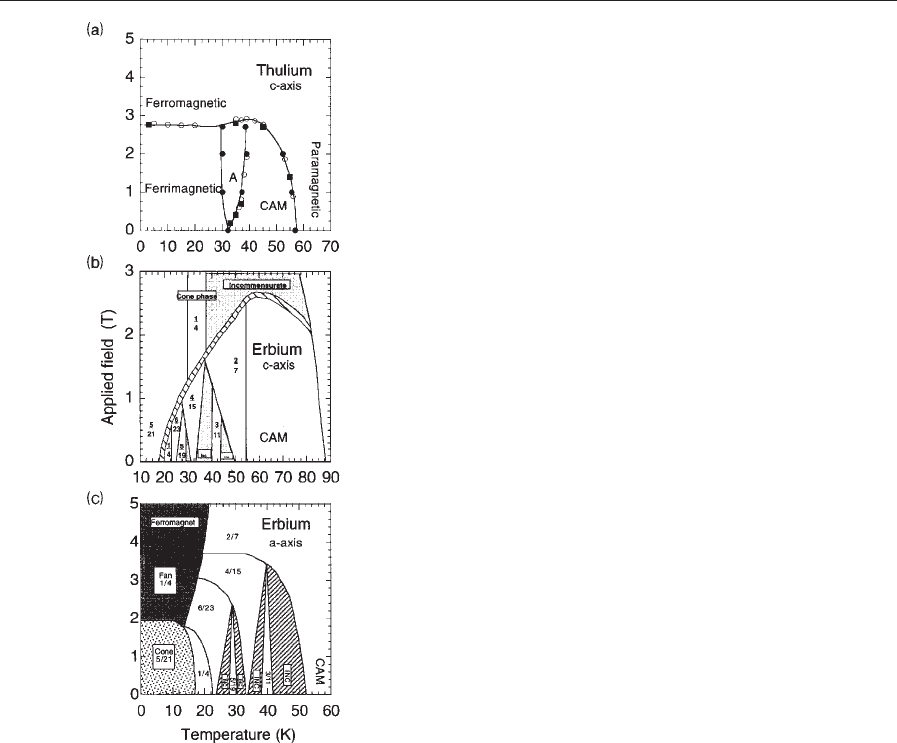

Figs. 2(a–c). In each of the phase diagrams, nomen-

clature is used to describe the magnetic phases and

has been left as it appears in the references.

2.1 Thulium

The magnetic phase diagram for thulium (Ellerby

et al. 1998) is presented in Fig. 2(a). There are five

distinct magnetic phase regions. They are labeled as

‘‘ferromagnetic,’’ ‘‘ferrimagnetic,’’ ‘‘c-axis modula-

ted’’ (CAM), ‘‘paramagnetic,’’ and ‘‘A.’’ The ferri-

magnetic structure is such that all the moments are

parallel to the c-axis with four moments pointing

‘‘up’’ and three moments ‘‘down’’ within the magnetic

unit cell, with a wave vector of Q ¼2/7c*(c* repre-

sents the reciprocal lattice vector of the c-axis). In the

ferromagnetic phase, all the moments point ‘‘up’’

along the c-axis. The moments in the paramagnetic

phase have no preferred orientation and may point in

any direction. The CAM phase is a magnetic struc-

ture in which the moments all point along the

c-axis, but the size of each moment varies from one

position to next in a sinusoidal manner (modulation)

within the magnetic unit cell. The nature of the phase

marked by ‘‘A’’ remains undetermined at this time.

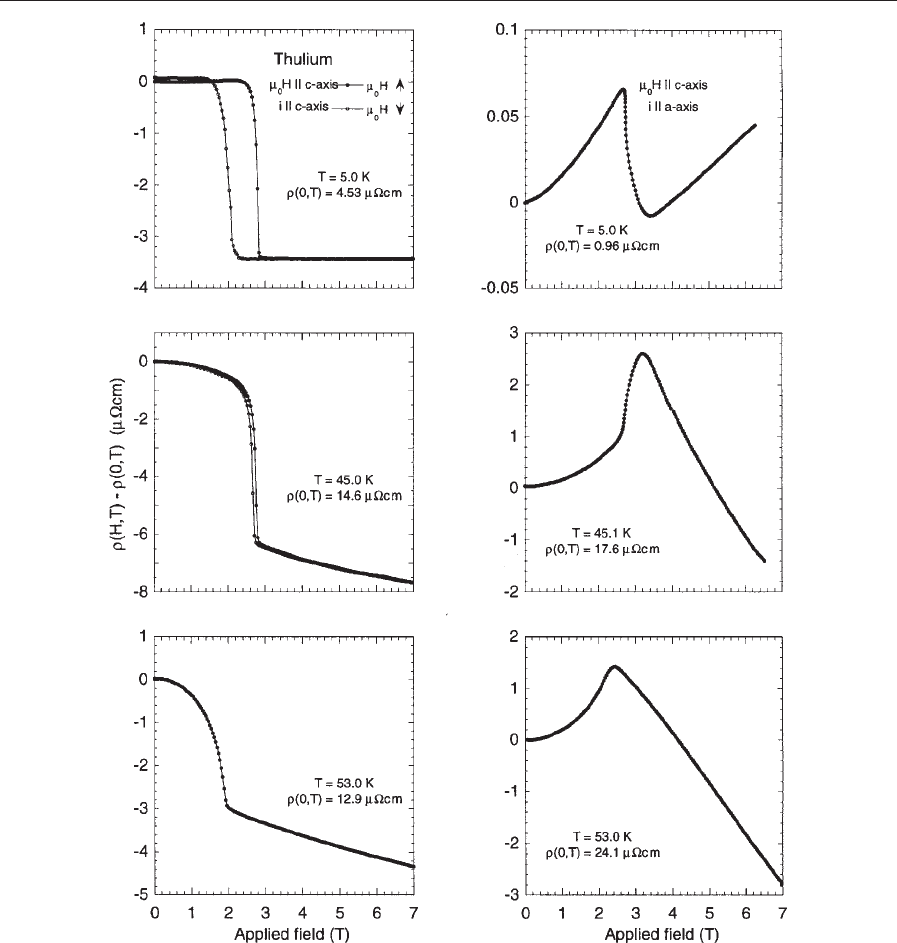

Having outlined the basic magnetic structures, the

reader is now referred to Fig. 3. This figure presents

two important measurement geometries, with the

magnetic field applied parallel to the c-axis in

both instances. On the left is the magnetoresistance

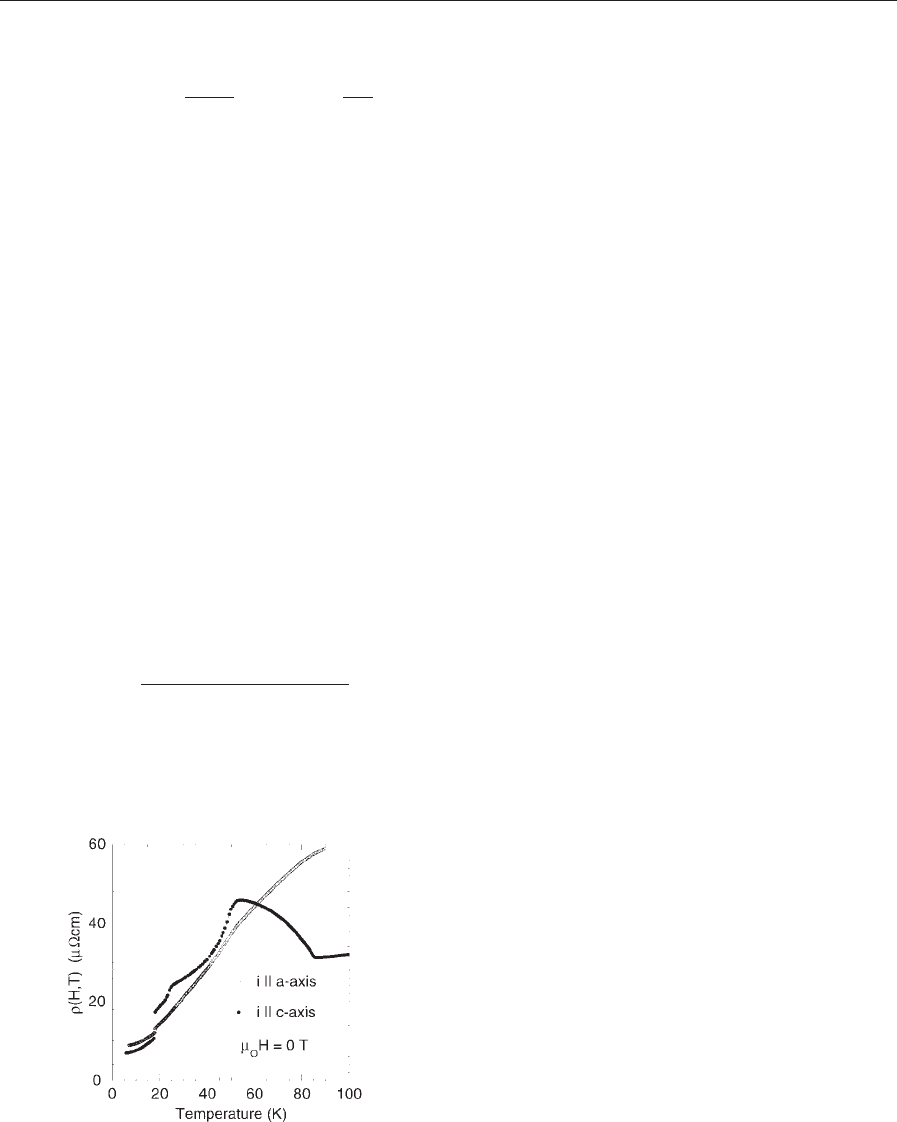

Figure 1

The temperature dependence of the longitudinal c(*)

and a-axis (J) resistivity for erbium.

157

Elemental Rare Earths: Magnetic Structure and Resistance, Correlation of

measured along the c-axis (longitudinal magnetore-

sistance), and the magnetoresistance for the a-axis

(transversal magnetoresistance) is on the right. For

the longitudinal geometry at T ¼5 K, the resistance

shows no change with applied field and then a large

decrease at 2.8 T, after which there is no change. This

may be understood using the model of Fermi-surface

modification (Mackintosh 1962, Elliott and Wedg-

wood 1963, Miwa 1963). The development of the

ferrimagnetic structure results in the removal of large

sections of the Fermi surface. As the field is increased,

the ferrimagnetic structure becomes unstable, and at

2.8 T all the moments flip to form the ferromagnetic

phase (see Fig. 2(a)). In doing so the modulation

wave-vector changes from Q ¼2/7c*toQ ¼0c*

(ferromagnetic). The additional potential is thus

removed, resulting in an increase of available Fermi

surface. In the transverse geometry (m

0

H8c-axis and

i8a-axis) at T ¼5 K, the features are different, with

the resistivity increasing quadratically with field.

Then, as the structure changes, there is a sharp

drop, followed by an almost linear increase. The

quadratic and linear portion of this behavior is un-

derstood to be normal magnetoresistance (Pippard

1989) (discussed in Magnetoresistance: Magnetic and

Nonmagnetic Intermetallics), and is associated with

the Lorentz force acting at the conduction electron

motion on the Fermi surface. The sharp decrease

suggests that there is a small portion of the Fermi

surface removed in the ferrimagnetic structure, which

is replaced on entering the ferromagnetic phase. At

T ¼45 K (i.e., in the CAM region in Fig. 2(a)), the

longitudinal measurement shows the same overall

trend. However, before the large transition there is a

smooth decrease. This is associated with the thermal

activation of the moments along the c-axis. This

activation results in fluctuations of the moment par-

allel and perpendicular to the c-axis, and results in

spin-fluctuation scattering. The applied field acts to

suppress these fluctuations, removing the scattering

center and therefore reducing the resistivity until, at

2.7 T, the moments flip parallel to the c-axis. Above

2.7 T the applied field suppresses fluctuations of the

moment away from the c-axis. The transverse mag-

netoresistance at T ¼45.1 K shows a smooth increase.

In this orientation, the field is perpendicular to the

magnetic moments and thus, as the field increases,

fluctuations transverse to the a-axis are enhanced,

leading to additional scattering centers. This behavior

is in accordance with the model (Yamada and Ta-

kada 1973). At the transition to the ferromagnetic

state, the effects of fluctuations of the moment in-

crease rapidly until full alignment at 2.7 T, after

which the effect of the field is to suppress the fluc-

tuations (Yamada and Takada 1973); at 3.2 T this

becomes the dominant process. For T ¼53.0 K, the

application of a magnetic field results in a quadratic

decrease in the resistivity for the longitudinal geom-

etry. This may be seen as a flipping of the moments in

a weak anisotropy field. The crystal field anisotropy

has a temperature dependence (Jensen and Mackin-

tosh 1991) which, at higher temperatures, allows the

moments to rotate smoothly off the easy axis. The

decrease in resistivity is attributed (Ellerby et al.

1998) to the replacement of Fermi surface. At

T ¼53.0 K, for the transverse geometry the resistiv-

ity is found to increase, and the process may be

viewed as a continuous spin-flop process (Yamada

and Takada 1973), with the moments eventually

aligning parallel to the c-axis at 2.3 T. For larger

fields, the fluctuations of the moments are systemat-

ically suppressed.

To summarize the case of thulium: the dominant

influence for the magnetoresistance of the longitudi-

nal geometry comes from the change in the Fermi

Figure 2

Magnetic phase diagrams for (a) thulium c-axis (Ellerby

et al. 1998); (b) erbium c-axis (McMorrow et al. 1992);

(c) erbium a-axis (Jehan et al. 1994).

158

Elemental Rare Earths: Magnetic Structure and Resistance, Correlation of

surface (Mackintosh 1962, Elliott and Wedgwood

1963). As the temperature is increased, the anisotropy

field decreases and spin-fluctuation scattering plays

an increasing role. For the transverse geometry,

the dominant scattering process derives from spin

fluctuations becoming enhanced by the applied

magnetic field; there is only a small effect due to

the change in Fermi surface, and this can only be

observed at very low temperatures. For the transverse

geometry at low temperatures, the Lorentz force

acting on the conduction electrons dominates. The

temperature dependence of the thulium c-axis has

been analyzed (Ellerby et al. 1998) for zero field and

4 T. From this analysis, Eqn. (4) has been found to

provide a good model of the data. The features in

Fig. 2(a) are all mapped using the longitudinal c-axis

Figure 3

Magnetoresistance for thulium with B8c-axis. Longitudinal c-axis on the left and transverse a-axis on the right.

159

Elemental Rare Earths: Magnetic Structure and Resistance, Correlation of