Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

is interrupted between plutonium and americium,

where the 5f states localize, and do not contribute to

bonding for heavier actinides. The reason for the lo-

calization (and loss of the 5f bonding energy) can be

found qualitatively in the gain of electron correlation

energy for atomic-like 5f states (which is partly lost in

the 5f band case). For details see Johansson and

Brooks (1993).

Thus the Stoner criterion (see Itinerant Electron

Systems: Magnetism (Ferromagnetism)) is not ful-

filled in light actinides because of too small N(E

F

)

and the Coulomb interaction parameter U. But these

materials can lower their electron energies by forming

different open crystal structures, sometimes of a very

low symmetry (in analogy to Jahn–Teller effect). The

best example of this phenomenon is plutonium, hav-

ing six allotropes, with the ground-state allotrope, a-

plutonium, showing a complicated monoclinic struc-

ture. A similar situation occurs in a-uranium, the

structure of which is orthorhombic, but an incom-

mensurate charge-density wave is formed below

T ¼43 K (Lander et al . 1994).

Due to the weakly magnetic character, super-

conductivity can appear at the beginning of the

actinide series. The critical temperatures T

c

are

1.368 K for thorium, 1.4 K for protactinium, 0.68 K

for a-uranium. For heavier actinides, superconduc-

tivity was found for americium (T

c

¼0.625 K).

Plutonium, the element on the verge of localiza-

tion, exhibits the most complex behavior. Its room

temperature phase, a-plutonium, is monoclinic with

16 atoms per unit cell. At T ¼395 K it undergoes a

phase transition to an even more complicated mono-

clinic b-phase with 34 atoms per unit cell. From the

remaining phases, most of the data is on the f.c.c. d-

phase with four atoms per unit cell, which has its

atomic volume expanded by 26% compared to the a-

phase, and which can be stabilized by several percent

by doping with aluminum, cerium, or gallium. Com-

paring to the data for a-plutonium given in Table 1, g

is strongly enhanced to 53710 mJmol

1

K

2

. For

details see Me

´

ot-Reymond and Fournier (1996),

where the properties of d-plutonium are discussed

in terms of a Kondo effect with the characteris-

tic Kondo temperature T

K

higher than the room

temperature.

The elements behind plutonium behave rather sim-

ilar to the lanthanide series. The analogy starts with

crystal structures. Americium, curium, berkelium,

and californium all have d.h.c.p. structures, but the

structures change and the 5f states delocalize under

external pressure, yielding low symmetry structures

of the light-actinides type (Benedict and Holzapfel

1993).

The nonmagnetic ground state of americium (ex-

hibiting low g and quite high Van Vleck susceptibil-

ity), can be understood in the framework of either

L–S or j–j coupling for the 5f

6

configuration. Most

information on curium was obtained on a fast

decaying isotope

244

Cm (half-life 18 years), which is

available in large amounts (milligrams) but displays

high self-heating and radiation damage. A maximum

magnetic susceptibility indicating antiferromagnetic

(AF) ordering was observed at T ¼52 K for this iso-

tope, and a simple AF order was indeed confirmed by

neutron diffraction. For

248

Cm, which has longer

half-life, but is available in smaller amounts only, the

AF order was indicated at T ¼64 K. Values of effec-

tive moment are compatible with m

eff

¼7.55 m

B

ex-

pected for the intermediate coupling model. Besides

the ground-state d.h.c.p crystal structure, a high tem-

perature f.c.c phase can occur in a low-temperature

metastable state. Its magnetic ordering temperature is

enhanced to T ¼205 K. Berkelium and californium

could be studied only in submilligram quantities. For

berkelium, AF ordering was deduced below T ¼34 K;

californium is probably ferromagnetic below approx.

51 K. Both materials display m

eff

values compatible

with free-ion theoretical values in the paramagnetic

state. Einsteinium, which could be studied in sub-

microgram quantity only, yields a moment of 11.3 m

B

,

which is even somewhat higher than the theoretical

value (Huray and Nave 1987).

3. Magnetic Properties of Actinide Intermetallic

Compounds

Similar to the pure actinide elements, the magnetic

properties of the compounds also reflect the gradual

filling of the incomplete 5f shell. In thorium com-

pounds the very small filling of the 5f states cannot

give rise to 5f magnetic moments, and compounds are

typically Pauli paramagnets with a susceptibility w

0

of

the order of 10

9

–10

8

m

3

mol

1

for intermetallic

compounds, where its value reflects the density of

states at E

F

. The ground state is frequently super-

conducting. Exceptions are compounds such as

Th

2

Fe

17

(T

C

¼295 K) and Th

2

Co

17

(T

C

¼1035 K),

in which magnetism is dominated by transition-metal

components.

In the compounds of uranium, neptunium, and

plutonium, magnetic ordering can appear in those

cases in which the actinide–actinide spacing is in-

creased to such an extent, that the 5f band narrowing

and consequent increase of the density of states at E

F

leads to the fulfillment of the Stoner criterion. The

proximity of these elements to the boundary between

the localized and itinerant character of the 5f elec-

tronic states makes them very sensitive to variations

of the environment. In the first approximation the

width of the 5f band can be taken as a function of the

overlap of the 5f atomic wave functions centered on

nearest neighbors, and the increase of the overlap can

be taken as a principal delocalizing mechanism of the

5f electrons. The situation is best documented for

uranium compounds, where the inter-uranium spac-

ing d

U-U

¼340–360 pm, called the Hill limit, is an

130

5f Electron Systems: Magnetic Properties

approximate boundary value of the spacing, corre-

sponding to the critical 5f–5f overlap. For smaller

spacings most of the compounds are nonmagnetic

(often superconducting). For d

U-U

larger than the

Hill limit they incline to a magnetically ordered

ground state. The value of the Hill limit should be

taken as very approximate; the width of the 5f band is

naturally affected also by the coordination number.

For compounds with d

U-U

larger than the Hill

limit, the principal control parameter is not the U–U

spacing, but the hybridization of the 5f states with

electronic states of other components. In particular,

in compounds with transition metals it is mainly the

overlap of the 5f states with the d states of the tran-

sition metal component in the energy scale which af-

fects the strength of the hybridization. The 5f states

remain pinned at the Fermi level in most cases,

whereas the late transition metals (as well as noble

metals), being much more electronegative, have par-

ticular d states shifted towards higher binding ener-

gies thus leaving the 5f–d overlap in energy scale

small. The reduced 5f–d hybridization leads to the

onset of 5f magnetism, whereas the d-states are

occupied more than in the pure d-element. Even if

the d-element itself is magnetically ordered (cobalt,

nickel, iron), in the compound with uranium it

behaves essentially as nonmagnetic (a similar effect

appears in thorium compounds).

Exceptions are compounds with very high content

of the transition metal component, in which the

d-magnetism can prevail. In compounds with earlier

d-metals such as iron or ruthenium the d-states ap-

pear closer to the Fermi energy and the 5f–d overlap

increases, leading typically to a nonmagnetic ground

state (as in UFeAl). But in some cases magnetic

moments appear both on uranium and transition-

metal ions. Prominent examples are Laves phases

with iron, all ordering ferromagnetically. Relatively

high T

C

values (UFe

2

162 K, NpFe

2

492 K, PuFe

2

564 K, AmFe

2

613 K) point to the dominance of the

iron–sublattice exchange interactions, but actinide

magnetic moments are non-negligible, reaching 1.1 m

B

per neptunium or 0.45m

B

for plutonium. The tiny to-

tal moment in the case of uranium in fact consists of

orbital (0.23 m

B

) and spin (0.22 m

B

) component, nearly

canceling each other.

In compounds with non-transition metals, it is

mainly the size of ligand atoms that affects the

hybridization. Compounds with larger ligands are

typically magnetic (e.g., UIn

3

), whereas those where

smaller ligands make the hybridization stronger

form broad bands with low N(E

F

) and are weakly

paramagnetic (USi

3

). Several characteristic groups of

uranium compounds can thus be distinguished in

Table 2.

The last group, heavy-fermion materials, comprises

those having a substantially enhanced g-coefficient of

specific heat, showing a coexistence of magnetic or-

dering and superconductivity of an unconventional

type (see Heavy-fermion Systems). In all uranium

compounds mentioned, the 5f states remain essen-

tially band-like, i.e., contributing to the bonding, and

therefore appearing at the Fermi level. The only ex-

ception known (at least from binary compounds) is

UPd

3

, for which the 5f localization has been con-

firmed by microscopic methods. Photoelectron spec-

troscopy exhibits in this case the 5f spectral intensity

displaced from the Fermi level to higher binding en-

ergies. Neutron scattering shows clear crystal electric

field (CEF) excitations, normally absent in spectra of

Table 2

Overview of the most characteristic groups of uranium intermetallics.

Characteristics Examples

Very high U content, small d

U-U

, weakly paramagnetic,

superconducting

U

6

Fe, U

6

Co, U

6

Ni

Higher U content, small d

U-U

, weakly paramagnetic,

normal ground state

UCo

2

,U

3

Si

2

Low d

U-U

(o340 pm), magnetic order of 5f moments

(very weak itinerant magnetism)

rare case (UNi

2

)

Intermediate d

U-U

(340–360 pm), typically ferromagnetic

ground state, itinerant magnetism, typically

T

C

o100 K

URh, UPt

Low U content, large d

U-U

, low 5f-ligand hybridization,

ferromagnetic ground state

rare case (UGa

2

)

Low U content, large d

U-U

, weak 5f-ligand

hybridization, AF ground state

UIn

3

, UGa

3

Low U content, large d

U-U

, strong 5f-ligand

hybridization, normal ground state

USi

3

, UNi

5

, UPt

5

Low U content, large d

U-U

spacing, heavy-fermion

behavior with different types of ground state

UPt

3

, UBe

13

, URu

2

Si

2

, UPd

2

Al

3

,U

2

Zn

17

, UCu

5

, UCd

11

131

5f Electron Systems: Magnetic Properties

uranium intermetallics, and the coefficient g reaches

only 5 mJ mol

1

K

2

.

Besides binary compounds there exist large groups

of ternary compounds, often including a transition

metal T and a non-transition metal X (UTX, U

2

T

2

X,

UT

2

X

2

), which follow the tendencies of the 5f ligand

hybridization mentioned above. The advantage of

studies of the 5f magnetism in such groups is that

both the transition and the non-transition metal

component can be varied, while the structure type,

i.e., the symmetry of environment of actinide atoms,

is preserved. This makes it possible to trace out in

more detail the cross-over from a nonmagnetic to

magnetic ground state.

Materials which are in the boundary region (i.e.,

nearly or weakly magnetic) show a variety of spin-

fluctuation features. Those with nonmagnetic ground

state exhibit Curie–Weiss behavior of magnetic sus-

ceptibility at high temperatures, but at low temper-

atures a broad maximum in w(T) appears (e.g.,

URuAl, UCoAl). Other types of spin fluctuators

are characterized by a plateau in w(T) below a char-

acteristic temperature, and a low-temperature upturn

as in URuGa (see Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998).

High ordering temperatures can be achieved, for

example, in ternary compounds of the UT

10

Si

2

type

(ThMn

12

structure type), in which both uranium and

the transition metal T (iron, cobalt) carry magnetic

moments. The highest T

C

¼750 K was recorded for

UFe

5

Co

5

Si

2

.

The occurrence of magnetic ordering in neptu-

nium-based compounds is dominated by mechanisms

analogous to their uranium counterparts. Important

information is obtained using

237

Np Mo

¨

ssbauer spec-

troscopy, which allows determination of microscopic

parameters of neptunium magnetism. In particular,

the magnetic hyperfine field B

hf

on the neptunium

nuclei was found to be approximately proportional to

the local neptunium magnetic moment m

Np

(Dunlap

and Kalvius 1985): B

hf

/m

Np

¼215 (T/m

B

). The fact

that the boundary between the magnetic and non-

magnetic behavior for different materials is not far

from the uranium isotypes demonstrates that for

neptunium compounds the mechanisms of the 5f

delocalization play a comparable role. Thus the

nonmagnetic behavior of neptunium in NpGe

3

and

NpRh

3

has to be attributed to the 5f–p and 5f–d

hybridization in analogy to UGe

3

and URh

3

. How-

ever, differences exist, too. For example, NpSn

3

is an

itinerant antiferromagnet, whereas USn

3

is a spin-

fluctuator not undergoing magnetic ordering. Such

differences can be generally attributed to a higher 5f

count or weaker 5f delocalization.

However, Np

2

Rh

2

Sn is a nonmagnetic spin flu-

ctuator, whereas U

2

Rh

2

Sn undergoes AF order

(T

N

¼24 K).

237

Np Mo

¨

ssbauer spectroscopy under

high pressure has been a convenient tool to distin-

guish different types of magnetically ordered com-

pounds. For those with more stable 5f moment the

neptunium moment does not decrease with pressure

in the gigapascal range while the ordering tempera-

ture increases (e.g., NpCo

2

Si

2

), whereas a pro-

nounced decrease of both parameters points to a

stronger 5f-moment instability e.g., in neptunium

Laves phases NpOs

2

or NpAl

2

.

4. Magnetic Properties of Other Actinide

Compounds

A large majority of actinide compounds, even with

nonmetallic elements, has a metallic character. The

magnetic behavior is dominated by the f–p hybridi-

zation, which plays a dual role. It leads to a delocal-

ization of the 5f states and mediates the exchange

interaction. The metallic character appears in most of

the rocksalt type of compounds, monopnictides AnX

(An ¼U, Np, Pu; X ¼P, As, Sb, Bi) and mono-

chalcogenides AnY (An ¼U, Np; Y ¼S, Se, Te),

which are magnetically ordered and reach apprecia-

ble magnetic phase transition temperatures e.g.,

T

N

¼213 K in USb or 285 K in UBi. However, plu-

tonium monochalcogenides are semimetallic and

nonmagnetic. Carbides, which are slightly under-stoi-

chiometric (AnC

1x

), are weakly magnetic for

An ¼Th, Pa, U. NpC

1x

is ferromagnetic below

T ¼225 K, whereas AF ordering is found up to about

300 K, depending on the x values. PuC

1-x

undergoes

AF ordering with T

N

ranging between 100 K and

30 K, depending on the stoichiometry. A large data

set exists for nitrides AnN. Whereas ThN and AmN

are weakly magnetic, magnetic ordering appears for

UN (T

N

¼53 K), NpN (T

C

E90 K), presumably also

in PuN (T

N

¼13 K) and CmN (T

C

¼109 K), and data

exist even for BkN (T

C

¼88 K). Of the other com-

pounds, a high magnetic ordering temperature can be

found, for example, in U

3

As

4

(T

C

¼196 K), U

3

Sb

4

(T

C

¼146 K), even 400 K for AF ordering in

U

2

N

2

As. USb

2

and UAs

2

are antiferromagnets with

T

N

¼205 K and 273 K, respectively.

Of the numerous oxides, the dioxides are the most

common. UO

2

and NpO

2

are antiferromagnets

(T

N

¼31 K and 25 K, respectively). These systems

are examples of the 5f localized magnetism, with at-

tributes such as crystal-field excitations and spin

waves, but the latter exhibits certain mysterious fea-

tures as tiny magnetic moments o0.1 m

B

/Np. For

further discussion see Localized 4f and 5f Moments:

Magnetism. PuO

2

is a weak paramagnet, presumably

due to a singlet crystal-field ground state for the 5f

4

ionic state. With hydrogen, uranium forms a trihyd-

ride known as a ferromagnet (T

C

¼180 K). AF order

was found in PuH

2

(T

N

¼30 K), whereas PuH

3

is

ferromagnetic (T

C

¼100 K). Neptunium hydrides are

weakly paramagnetic, which can be understood as

being due to CEF effects in the case of the 5f

4

ionic

state (for details see Wiesinger and Hilscher 1991).

Hydrogen can be absorbed also by a number of

132

5f Electron Systems: Magnetic Properties

binary and ternary intermetallic compounds. Similar

to elemental light actinides, it strongly supports the

tendency to form local 5f magnetic moments and to

give rise to magnetic order. This can at least partly

be attributed to 5f-band narrowing due to enhanced

inter-actinide spacing.

5. Orbital Momen ts in Light Actinides

Although the majority of the light actinides and their

intermetallic compounds is characterized by itinerant

5f-states, an important difference with 3d magnetics

is the energy of the spin-orbit coupling D

S-O

and

the width of the 3d (5f) band W

3d

(W

5f

). Whereas

D

S-O

5W

3d

, the respective values in the light actinides

become of comparable magnitude because D

S-O

is of

the order of eV. Due to the strong spin-orbit inter-

action, typically a large orbital magnetic moment m

L

is induced. It is antiparallel to the spin moment for

uranium, in analogy with the light lanthanides and

the third Hund’s rule stating that the total angular

momentum is given by J ¼LS. The existence of

such orbital moments for the 5f-band systems was

first revealed from band structure calculations in-

volving a spin-orbit interaction term coupling the

spin and orbital moment densities (see Density Func-

tional Theory: Magnetism). Experimentally this was

confirmed by studies of the neutron form-factor,

which adopts a very specific shape with a maximum,

especially if spin and orbital moments are of the same

size. Such a case, at which the total moment is close

to zero, but the spatial extent of spin and orbital

moment densities is different, was observed, for ex-

ample, in UNi

2

or UFe

2

. In the latter case the ura-

nium moment consists of the orbital part m

L

¼0.23 m

B

and a spin part m

S

¼0.22 m

B

. Recently, orbital mo-

ments became accessible also in x-ray scattering stud-

ies using synchrotron radiation (see Magnetism:

Applications of Synchrotron Radiation).

A different sensitivity of spin or orbital moments

to external variables led to the assumption that the

ratio of orbital and spin moment should reflect the

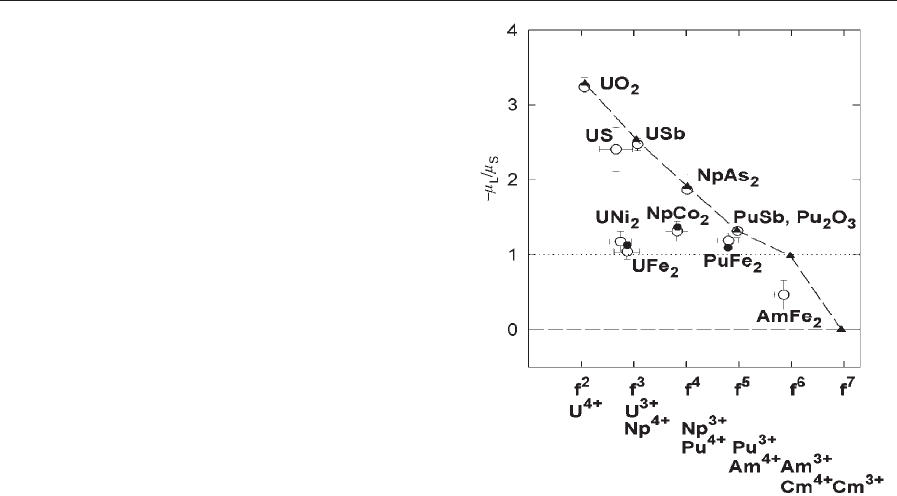

degree of the 5f-delocalization. Indeed, as seen from

Fig. 1, the compounds showing the least delocalized

nature of the 5f states (UO

2

, USb, NpAs

2

, PuSb)

are located on the line representing values of m

L

/m

S

of a free 5f

n

ion. On the other hand, magnetically

ordered materials with presumably the most itinerant

5f states (UFe

2

, UNi

2

, NpCo

2

, PuFe

2

) have this ratio

close to 1.

Relatively large orbital moments induced by mag-

netic field exist probably even in weakly paramag-

netic materials such as uranium metal. Surprisingly,

in an external magnetic field the spin and orbital

magnetic moments orient parallel, as shown by a

simple balance of the Zeeman and spin-orbit energy

in the case of weak susceptibility (for details see

Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998).

6. Exchange Inter actions and Magnetic

Anisotropy

Exchange interactions in materials with localized 5f

states can be seen as being analogous to regular lan-

thanides, for which the indirect exchange of the

RKKY type is a good approximation. The other

limit, systems with strongly itinerant 5f states, can be

understood in terms of the Stoner–Edwards–Wohlf-

arth theory for itinerant magnets (see Itinerant Elec-

tron Systems: Magnetism (Ferromagnetism)), in

which the ordering temperature is proportional to

the ordered moment. For intermediate delocalization,

when the direct 5f–5f overlap is negligible, a dual role

of the 5f ligand hybridization has to be taken into

account. It is a primary mechanism of destabilizing

the 5f magnetic moments, but because the spin in-

formation is conserved in the hybridization process, it

leads to an indirect exchange coupling. Maximum

ordering temperatures can consequently be expected

for a moderate strength of hybridization, because a

strong hybridization completely suppresses magnetic

moments, whereas a weak one leaves the moments

intact, but their coupling is weak.

Figure 1

Ratio of the orbital m

L

and spin m

S

moments in a number

of magnetically ordered materials plotted as a function

of the number of the 5f electrons. The triangles,

connected by a dashed line, are the values derived from

single-ion theory including intermediate coupling.

Experimental results are shown by open circles. Results

of band structure calculations are shown by solid circles.

For details see Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998.

133

5f Electron Systems: Magnetic Properties

A model leading to realistic results have been

worked out by Cooper et al. (1985) on the basis of

the Coqblin–Schrieffer approach. The mixing term in

the hamiltonian of the Anderson type is treated as a

perturbation, and the hybridization interaction is re-

placed by an effective f-electron-band-electron reso-

nant exchange scattering. Considering an ion-ion

interaction as mediated by different covalent-bonding

channels, each for particular magnetic quantum

number m

l

, the strongest interaction is for those or-

bitals that point along the ion–ion bonding axis, which

represents the quantization axis of the system. The two

5f ions maximize their interaction by compression of

the 5f charge towards the direction to the nearest 5f

ion. This has serious impacts on magnetic anisotropy,

because it means a population of the 5f states with

orbital moments perpendicular to the bonding axis.

This interaction prefers a strong ferromagnetic

coupling of the actinide moments along the bonding

direction. There is no special general tendency to ferro-

or antiferromagnetism in the perpendicular direction,

where the interaction is much weaker, and can be of a

size comparable to that of the ‘‘background’’ isotropic

exchange interaction of the standard RKKY type.

Unlike such two-ion hybridization mediated aniso-

tropy, crystal electric field (single-ion) effects control

the type and strength of magnetic anisotropy for

materials with the localized 5 f states, in analogy to

lanthanide systems.

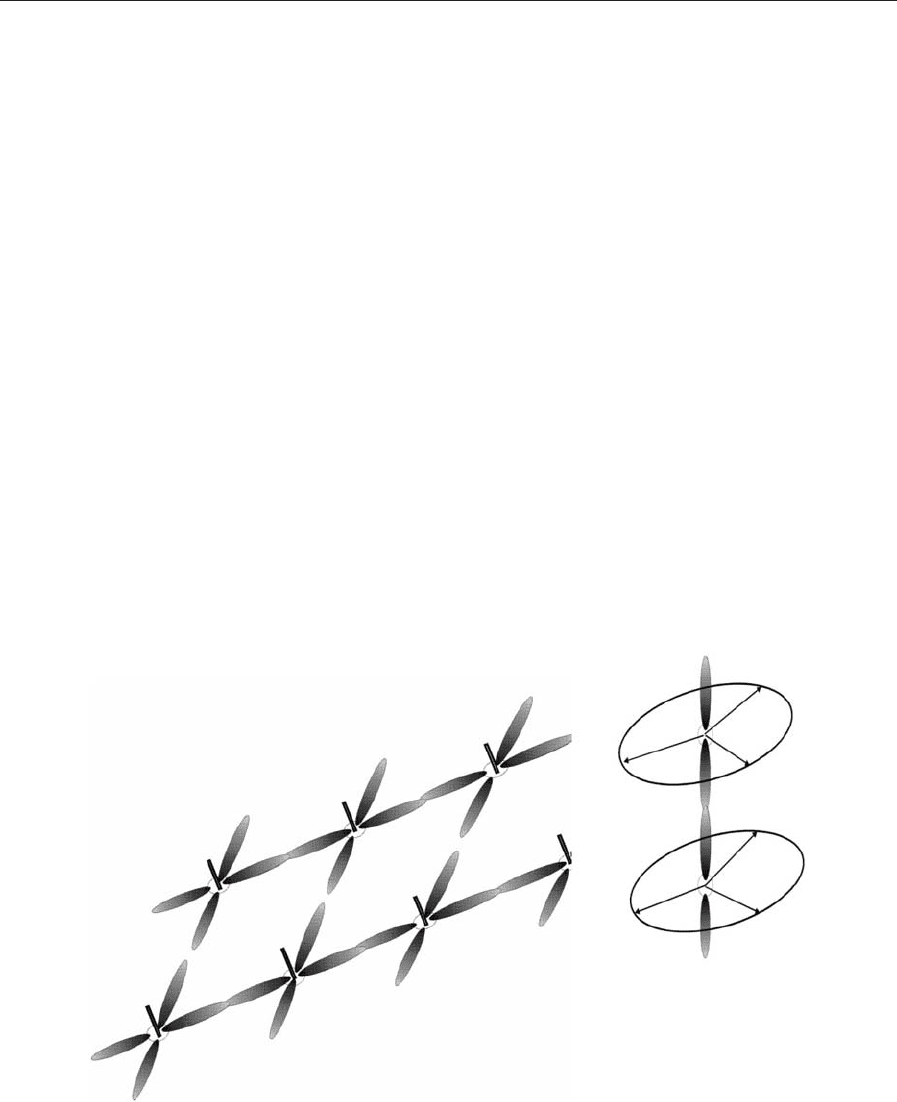

The two-ion anisotropy, for which orbital mo-

ments are necessary prerequisite, has been observed

especially in numerous uranium compounds, for

which single-crystal magnetization data exist. The

tendency for moments to orient perpendicular to the

U–U bonding links leads to a uniaxial anisotropy in

crystal structures with uranium atoms organized in

planes with a short in-plane U–U spacing and larger

inter-plane spacing. The case of uranium linear

chains leads to a planar type of anisotropy (see

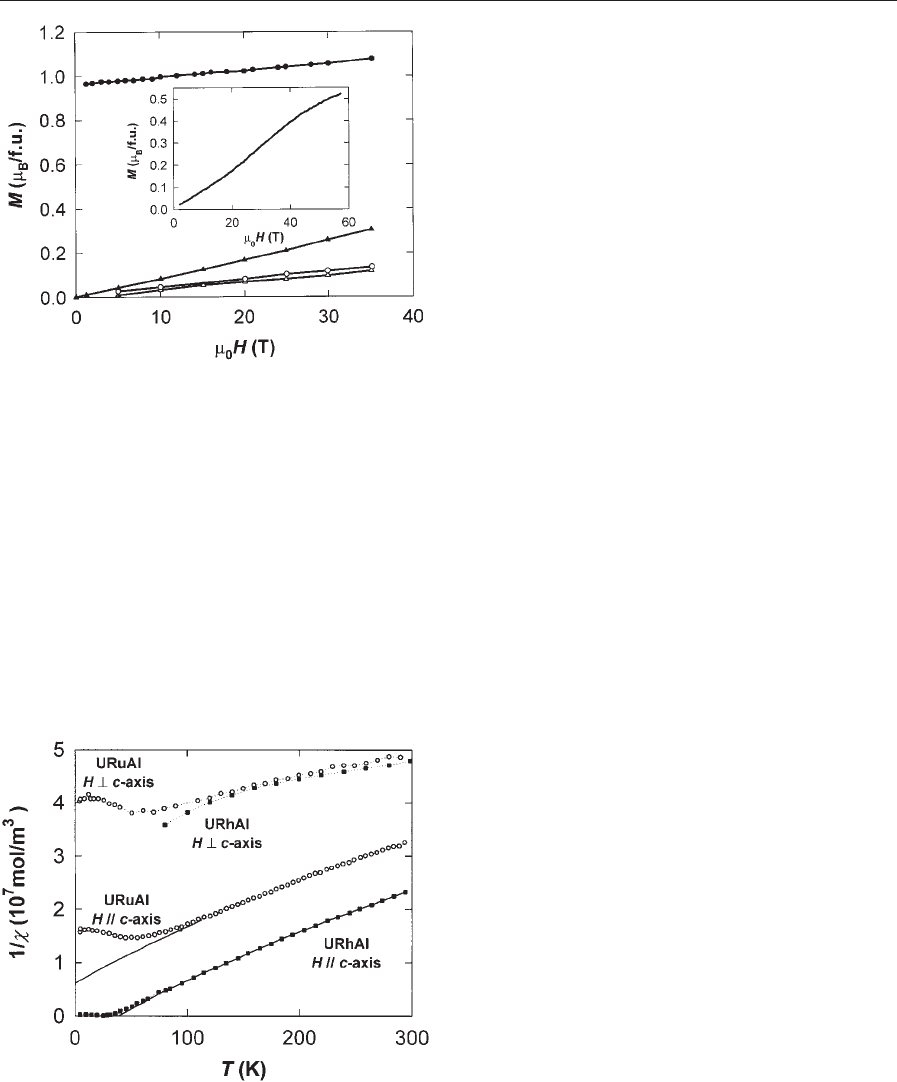

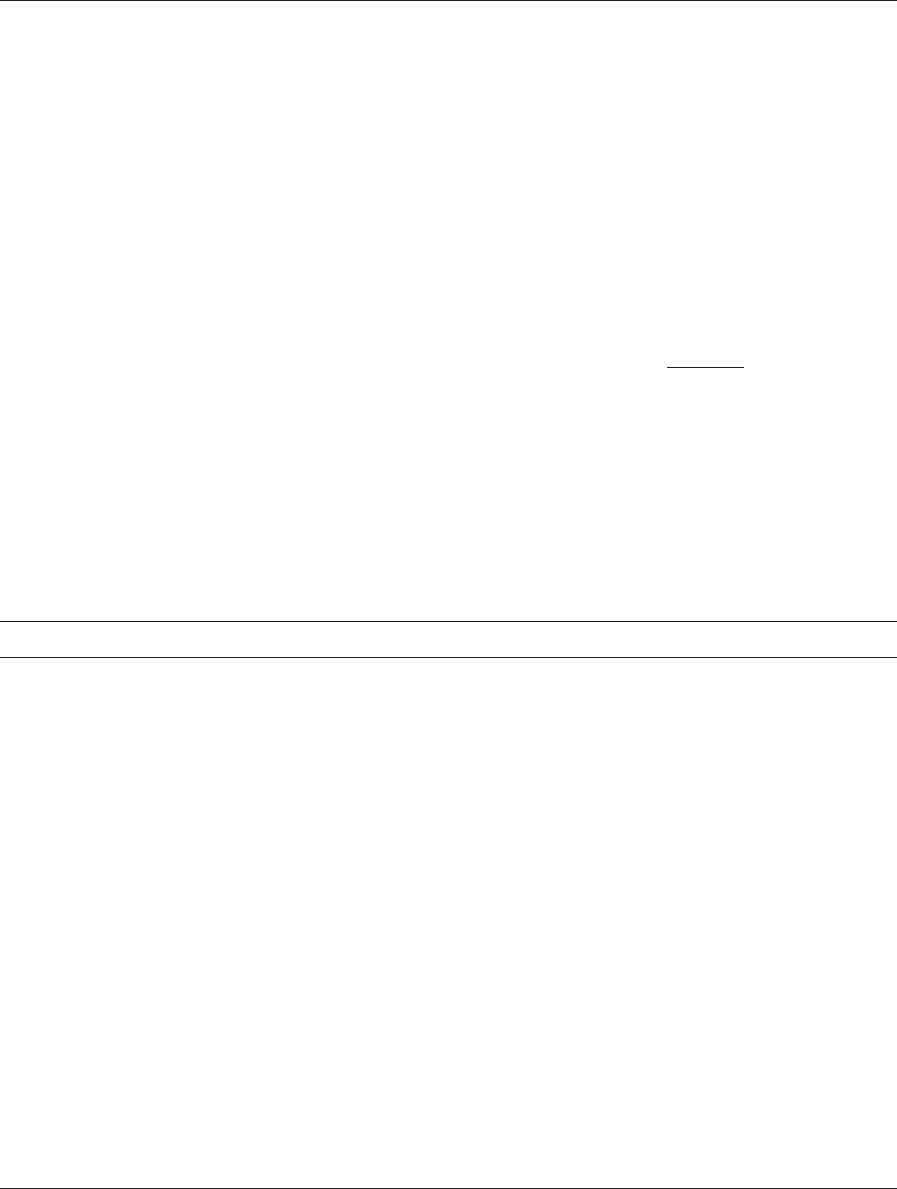

Fig. 2). The strength of the anisotropy, which is well

observable both in magnetically ordered and para-

magnetic phases, can be estimated in some cases from

the difference of the paramagnetic Curie tempera-

tures (see Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction)

when the susceptibility is studied with the magnetic

field along different crystallographic directions. An-

other estimate can be obtained from the anisotropy

field, at which the extrapolated magnetization curves

along different directions would intersect each other.

Typically values of 10

2

–10

3

Kor10

2

–10

3

T are ob-

tained in this way (see Figs. 3 and 4).

For large groups of isostructural compounds, the

same type of anisotropy is, as a rule, found irrespec-

tive of the non-actinide components. Examples are

the strong uniaxial anisotropy of UTX compounds

(with hexagonal structure of the ZrNiAl type) or

tetragonal UT

2

X

2

compounds, both with strong

uranium bonding within planes perpendicular to the

Figure 2

Schematic view illustrating how the bonding and easy-magnetization directions are related in light actinides.

On the left, the easy-axis anisotropy for planar bonding; on the right, the easy-plane anisotropy for columnar

bonding.

134

5f Electron Systems: Magnetic Properties

hexagonal (tetragonal) axis, and uranium moments

(or higher susceptibility) along this axis.

7. Magnetic Structures

Both specific mechanisms in light-actinide materials,

the magnetic anisotropy and exchange interactions,

affect their magnetic structure types. Strong aniso-

tropy frequently leads to collinear modulated struc-

tures (spin-density waves), which are preferred over

noncollinear equal moment structures. The reason is

that the anisotropy energy is typically stronger than

the exchange coupling energies. Noncollinear mag-

netic structures are stable if the easy-magnetiza-

tion directions on different sites are noncollinear,

as in U

2

Pd

2

Sn, where they are orthogonal. Also in

cases in which the lattice symmetry imposes no spe-

cial requirements on the moment’s directions (see

Sandratskii 1998), noncollinear equal-moment struc-

tures appear (e.g., UPtGe). Types of magnetic struc-

tures are also affected by the strong ferromagnetic

coupling along strong bonding directions (see the

hybridization-induced exchange model, above). For

example, UTX compounds with hexagonal structure

of the ZrNiAl type, form magnetic structures con-

sisting of ferromagnetic basal-plane sheets, whereas

the inter-sheet exchange interaction is weaker and can

be of ferro- or antiferro-type, leading to a variety of

stacking sequences along the hexagonal axis. In this

case, ferromagnetic-like alignment can be obtained

in moderate magnetic fields applied along the AF

stacking direction.

See also: Electronic Configuration of 3d,4f and 5f

Elements: Properties and Simulations

Bibliography

Benedict U, Holzapfel W B 1993 High-pressure studies—Struc-

tural aspects. In: Gschneidner K A Jr, Eyring L, Lander G H,

Choppin G R (eds.) Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry

of Rare Earths. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 17, pp. 245–300

Cooper B R, Siemann R, Yang D, Thayamballi P, Banerjea A

1985 Hybridization-induced anisotropy in cerium and acti-

nide systems. In: Freeman A A, Lander G H (eds.) Handbook

on the Physics and Chemistry of the Actinides. Elsevier, Am-

sterdam, Vol. 2, pp. 435–500

Dunlap B D, Kalvius G M 1985 Mo

¨

ssbauer spectroscopy on

actinides and their compounds. In: Freeman A, Lander G H

(eds.) Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of the Acti-

nides. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 2, pp. 329–434

Huray P G, Nave S E 1987 Magnetic studies of transplutonium

actinides. In: Freeman A A, Nave S E (eds.) Handbook on the

Physics and Chemistry of the Actinides. Elsevier, Amsterdam,

Vol. 5, pp. 311–72

Johansson B, Brooks M S S 1993 Theory of cohesion in rare

earths and actinide. In: Gschneidner K A Jr, Eyring L,

Lander G H, Choppin G R (eds.) Handbook on the Physics

Figure 3

Illustration of the strong uniaxial anisotropy observed in

the hexagonal UTX compounds (ZrNiAl structure

type), in particular in URhAl–ferromagnet, T

C

¼27 K

(circles), and URhAl–paramagnet (triangles).

Magnetization at T ¼4.2 K was measured as a function

of magnetic field applied along the c-axis (filled symbols)

and a-axis (open symbols). The comparison shows that

the response along the a-axis is practically the same,

unaffected by ordered magnetic moments oriented along

the c-axis in URhAl. The inset shows a similar

experiment on field-oriented powder of URuAl

extending the field range. The noticeable S-shape is

attributed to the suppression of spin fluctuations in high

magnetic fields (see Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998).

Figure 4

Temperature dependence of inverse magnetic

susceptibility for the same materials as shown in Fig. 3,

illustrating the same type of anisotropy of the

paramagnetic behavior.

135

5f Electron Systems: Magnetic Properties

and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 17,

pp. 149–244

Lander G H, Fisher E S, Bader S D 1994 The solid-state prop-

erties of uranium—a historical perspective and review. Adv.

Phys. 43, 1–110

Me

´

ot-Reymond S, Fournier J M 1996 Localization of 5f elec-

trons in d-plutonium: evidence for the Kondo effect. J. Alloys

Compound. 232, 119–25

Sandratskii L M 1998 Noncollinear magnetism in itinerant

electron systems—theory and applications. Adv. Phys. 47,

91–160

Sechovsky´ V, Havela L 1988 Intermetallic compounds of ac-

tinides. In: Wohlfarth E P, Buschow K H J (eds.) Ferromag-

netic Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 4, pp. 309–491

Sechovsky´ V, Havela L 1998 Magnetism of ternary intermetal-

lic compounds of uranium. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Hand-

book of Magnetic Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 11,

pp. 1–289

Wiesinger G, Hilscher G 1991 Magnetism of hydrides. In: Bus-

chow K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic Materials. Elsevier,

Amsterdam, Vol. 6, pp. 511–84

L. Havela

Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

Electron Systems: Strong Correlations

The physics of strongly correlated electron systems

originates primarily from the presence of an inner d

or f shell in one of the atoms embedded in the system

considered. The d electrons in transition elements and

the 4f or 5f electrons in rare earths or actinides are

generally well localized and correlated. The physics of

strongly correlated electron systems is the subject of

many experimental and theoretical studies and we

will summarize here the main points.

The correlations tend firstly to favor the existence

of magnetism which is because of open inner d or f

shells, as observed in pure iron, cobalt, or nickel in

the 3d series, in the rare-earth metals, and in actinide

metals after americium. Magnetism is also observed

in many ionic, insulating, or metallic systems con-

taining these magnetic elements.

The generic term of strongly correlated electron

systems is mostly reserved to metallic systems where

there exists a strong interaction or hybridization be-

tween the inner d or f electrons and the conduction

electrons. This type of physics started from the ex-

perimental observation of the resistivity minimum in

dilute alloys such as

CuFe, CuMn, LaCe, or YCe, the

theoretical concept of ‘‘virtual bound state’’ intro-

duced by Friedel (1956), 1958), the derivation of the

hybridization Anderson (1961) model, and the expla-

nation by Kondo (1964) of the resistivity minimum.

After the exact solution of the Kondo effect at low

temperatures for a single impurity (Wilson 1975),

there are many topics involved in the physics of

strongly correlated electron systems. The main topic

concerns the so-called ‘‘heavy-fermion’’ behavior ob-

served in many cerium or other anomalous rare-earth

compounds, after its first observation in CeAl

3

(And-

res et al. 1975). In the ‘‘Kondo lattice,’’ there exists a

strong competition between the Kondo single impu-

rity behavior and the magnetism, and the behavior

around the quantum critical point of the Doniach

(1977) diagram has been extensively studied.

The metal–insulator transition, introduced by the

work of Mott (1974), and the study of compounds

such as manganites are also a very important part of

this type of physics. The discovery of superconduc-

tivity in the CeCu

2

Si

2

compound by Steglich et al.

(1979), and in some cerium compounds at high pres-

sure and uranium compounds at normal pressure is

also a very noteworthy result. Strong correlations

appear to be the origin of the high T

c

superconduc-

tivity, which was discovered by Bednorz and Muller

(1986), but this question is still not answered. Finally,

the study of strongly correlated electron systems

has considerably contributed to the development of

new experimental techniques, such as high-accuracy

photoemission or related experiments, neutron scat-

tering, and NMR or muon spectroscopy, as well as to

all kinds of magnetic and transport measurements at

extremely low temperature and high pressures, and

under very large magnetic fields.

1. The Series of Rare-earth and Actinide Metals

The first systems studied that could be considered as

strongly correlated electron ones were dilute alloys

with 3d transition element impurities embedded in a

host such as copper; now the most studied systems

contain rare earths and actinides.

Most of the rare-earth metals have a magnetic

moment given by Hund’s rules (see Magnetism in

Solids: General Introduction and Localized 4f and 5f

Moments: Magnetism), corresponding to the 4f

n

(n an

integer) configuration. For example, gadolinium, in

the middle of the series, has a 4f

7

configuration with a

magnetic moment equal to 7 m

B

in the ferromagnetic

phase below the Curie temperature of 293 K, and

there is no change in the number of 4f electrons under

pressure, even a very high one. It follows that the

‘‘valence,’’ taken here as equal to the number of con-

duction electrons, remains constant and equal to 3.

Thus, most of the rare-earth metals have a stable

valence of 3 and are called ‘‘normal’’ (Coqblin 1977).

However, some rare-earth metals undergo a change

of valence under different experimental conditions

(pressure, temperature, or relative composition in

the case of alloys and compounds containing these

metals) and they are called ‘‘anomalous.’’ The best

example of the series is cerium, the first element after

lanthanum, which varies or fluctuates between the

two configurations 4f

0

and 4f

1

. Cerium metal has a

very peculiar phase diagram with several phases,

136

Electron Systems: Strong Correlations

which is discussed below. However, dilute cerium al-

loys such as

LaCe or YCe, which are magnetic with a

magnetic moment corresponding to the 4f

1

configu-

ration, show at low temperatures a resistivity mini-

mum which was first accounted for by Kondo (1964).

This Kondo effect, which has since been observed in

many alloys and compounds containing cerium or

other anomalous rare earths, has been the subject of

many studies.

The actinide series (see 5f Electron Systems: Mag-

netic Properties) corresponds to the filling of the 5f

inner shell, but clearly the 5f electrons are less local-

ized than the 4f electrons of the rare-earth metals. In

fact, the degree of localization of the 5f electrons lies

between that of the 4f electrons and that of the d

electrons of the transition elements. The actinide

metals of the first series up to americium are not

magnetic and magnetism arises only in the middle of

the series for curium. Thorium and protactinium, at

the beginning of the series, are not magnetic. Urani-

um, neptunium, and plutonium are close to being

magnetic, and most of the properties of neptunium

and plutonium can be accounted for by the classical

model of spin fluctuations. Finally, the ionic model

becomes valid for americium and the following acti-

nides; americium is not magnetic because of the pres-

ence of the 5f

6

configuration, while the following two

actinides have magnetic moments corresponding to

the 5f

7

and 5f

8

configurations. A strong hybridization

between the 6d and 5f electrons, which yields an ef-

fective broadening of the 5f band and gives a non-

magnetic situation, has been proposed to explain this

phenomenon (Jullien et al . 1972). Many compounds

of uranium, neptunium, and plutonium have been

studied and various physical situations have been

observed, from a clear magnetic situation with a

magnetic order at low temperatures to a nonmag-

netic, heavy-fermion situation. Moreover, some ura-

nium compounds are both magnetically ordered, with

a heavy-fermion behavior, and superconducting at

low temperatures.

2. The Friedel Sum Rule and the Anderson

Hamiltonian

As previously explained, transition or rare-earth

elements in dilute alloys can be magnetic and in an

ionic configuration, but many dilute alloys or com-

pounds contain d or f elements that are in an inter-

mediate situation. This is typically the case for

CuMn

alloys or cerium compounds. There is a strong inter-

action between the localized electrons (d or f) on the

impurity sites and the conduction electrons that are

almost free in the lattice and are generally scattered

by the localized electrons. Localized magnetism on

the impurity comes from the Coulomb integral, U,

and the criterion for the occurrence of localized mag-

netism is Ur(E

F

)41, corresponding, therefore, to

strong electron correlations and a large density of

states, r(E

F

), at the Fermi energy. Pioneering work

discussing this problem provided the ‘‘Friedel sum

rule’’ (Friedel 1954), which connects the difference of

charge, Z, between the localized electrons on the im-

purity and the conduction electrons to the phase

shifts introduced by the scattering of the conduction

electrons. For example, in

CuMn dilute alloys, Z

represents the difference of charge between copper

and manganese and corresponds to essentially the

difference in occupation of the 3d shell.

The Friedel sum rule gives a relationship between

Z and the phase shifts, d

l

, at the Fermi energy cor-

responding to the different partial wave functions

scattered by the impurity:

Z ¼

1

p

X

l;s

ð2l þ 1Þd

s

l

ð1Þ

The phase shifts correspond to the different l val-

ues of the orbital momentum. Friedel (1956, 1958)

developed the model of ‘‘virtual bound state’’ to de-

scribe the case of dilute aluminum- or copper-based

alloys with 3d impurities. The only nonzero (or mul-

tiple of p) phase shift is that of l ¼2 and d

2

increases

from 0 to p when the 3d shell fills up, passing roughly

through a maximum value of p/2 for manganese.

Since the residual resistivity varies as sin

2

d

2

, this der-

ivation explains the maximum of the residual resis-

tivity observed in the 3d series for aluminum-based

dilute alloys with 3d impurities. The same type of

derivation explains the two maxima observed in the

case of copper-based alloys that are magnetic, be-

cause there are two different phase shifts for the two

spin directions.

Anderson (1961) introduced a Hamiltonian given

by

H ¼

X

k;s

e

k

n

ks

þ E

0

X

s

n

f s

þ Un

f m

n

f k

þ

X

k;s

ðV

kf

c

ks

c

f s

þ V

fk

c

f s

c

ks

Þð2Þ

where the 3d (or 4f or 5f) level located at the energy

E

0

is hybridized with the conduction electrons by the

hybridization parameter V

kf

. The Coulomb integral,

U, for the localized electrons is generally taken as

very large, corresponding, therefore, to the case of

strong correlations. For a single impurity, the density

of states for the localized electrons has a Lorentzian

shape with a width of D ¼pr

s

V

2

kf

(where r

s

is the

density of states of the conduction band at the Fermi

energy), which leads to a nonintegral number of lo-

calized electrons. The Hamiltonian is self-consistently

solved within the Hartree–Fock approximation and

this model has also been applied to describe the oc-

currence of magnetism in transition element-based

alloys. For example,

CuMn alloys are magnetic while

AlMn alloys are not, because the density of states at

137

Electron Systems: Strong Correlations

the Fermi energy, E

F

, for the localized electrons hy-

bridized with the conduction electrons is larger in

copper than in aluminum.

3. The Kondo Effect

The starting point of the history of the Kondo effect

is the first calculation performed by Kondo (1964) to

account for the observed experimental evidence of a

resistivity minimum in magnetic dilute alloys such as

CuMn, CuFe, YCe, or LaCe. The first observed re-

sistivity minimum in

CuFe dates from 1931. In such

dilute alloys, the transition element impurities are

magnetic and the system is well described by the

classical exchange Hamiltonian given by

H ¼Js

c

S

f

ð3Þ

where the localized spin, S

f

, on the impurity interacts

with the spins, s

c

, of the conduction electrons coming

from the host. The exchange constant, J, can be ei-

ther positive (corresponding to a ferromagnetic cou-

pling) or negative (antiferromagnetic coupling). It

follows that a localized spin, S

f

, on site i interacts

with another localized spin on site j by an indirect

mechanism involving the conduction electrons

through the exchange interaction given by Eqn. (3).

This indirect interaction between two localized elec-

tron spins is called the ‘‘Ruderman–Kittel–Kasuya–

Yosida’’ (RKKY) interaction (Ruderman and Kittel

1954). The RKKY interaction (see Magnetism in Sol-

ids: General Introduction) decreases as a function of

the distance, R, between the two sites i and j as

cos(k

F

R)/(k

F

R)

3

.

Kondo computed the magnetic resistivity, r

m

,up

to third order in J (or in second-order perturbation)

and found the following:

r

m

¼ A7J7

2

S ð S þ 1Þ 1 þ Jrlog

k

B

T

D

ð4Þ

where r is the density of states for the conduction

band at the Fermi energy, A is a constant, and S is

the value of the spin for the localized electrons. We

see that, for a negative J value, the magnetic resis-

tivity decreases with increasing temperature. Thus,

the total resistivity, which is the sum of the mag-

netic resistivity and the phonon resistivity which in-

creases with temperature, passes through a minimum

(Kondo 1964, 1969). A negative J value corresponds

to an antiparallel coupling between the localized and

conduction electron spins and the preceding treat-

ment is valid only at sufficiently high temperatures

above the so-called ‘‘Kondo temperature,’’ T

k

, given

by

k

B

T

k

¼ Dexp

1

7Jr7

ð5Þ

where D is a cut-off corresponding roughly to the

conduction band width. The magnetic susceptibility

decreases above T

k

as 1/T, as in a Curie–Weiss law

(see Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction). The

different transport, magnetic, and thermodynamic

properties of a Kondo impurity have been extensively

studied by perturbation in the so-called ‘‘high-

temperature’’ regime (i.e., above T

k

). It is clear that,

below T

k

, the perturbative treatment is not valid and

the low-temperature behavior is completely diffe-

rent from the previously described high-temperature

behavior.

At ‘‘low temperatures’’ (T5T

k

), a so-called heavy-

fermion behavior (see Heavy-fermion Systems) has

been observed in many cerium Kondo compounds,

such as CeAl

3

, CeCu

6

, or CeCu

2

Si

2

. This behavior

was first observed experimentally in CeAl

3

, where

Andres et al. (1975) found an extremely large elec-

tronic specific heat constant g ¼1.62 Jmol

1

K

2

and

an AT

2

law for the resistivity with a very large co-

efficient A ¼35 mOcmK

2

. An extremely high value

of g ¼8 Jmol

1

K

2

has been obtained in the YbBiPt

compound, which is the maximum observed g value

(Lacerda et al. 1993).

The theoretical problem of a single Kondo impu-

rity has been exactly solved at T ¼0 by Wilson (1975)

using the renormalization group technique on the

exchange Hamiltonian (Eqn. (3)) with a negative J

value. Wilson was the first to show numerically that

the exact T ¼0 solution is a completely compensated

singlet formed by the antiparallel coupling between

the conduction electron spin, s

c

¼1=2 , and the lo-

calized electron spin, S

f

¼1=2. An analytical exact

solution of the single Kondo impurity problem has

been obtained by the Bethe–Ansatz method for both

the classical exchange and the Coqblin–Schrieffer

Hamiltonians (Andrei et al. 1983, Schlottmann 1982,

Tsvelick and Wiegmann 1982). The exact solutions

have given a clear description of the Kondo effect,

but since it is difficult to use them for computing the

different physical properties, sophisticated mean

field-type methods have been introduced, such as

the ‘‘slave boson’’ method (Read and Newns 1983,

Coleman 1984) or the method using correlators

(Lacroix and Cyrot 1979). A dynamical mean-field

theory that takes the limit of infinite dimension (or

a very large lattice coordination number) has been

introduced because this limit can yield an exact map-

ping of lattice models onto quantum impurity models

(Georges et al. 1996). We can also mention many

works describing dynamical effects or spectro-

scopic properties and both the impurity Kondo and

Anderson problems including dynamical proper-

ties have been solved by different theoretical tech-

niques, in particular by the renormalization group

technique (Allen et al. 1986). There is a tremendous

literature on this subject and the reader can find very

interesting reviews in Hewson (1992) or Bickers

(1987).

138

Electron Systems: Strong Correlations

The low-temperature (i.e., T5T

k

) properties of a

Kondo impurity are those of a ‘‘Fermi liquid’’ and

can be summarized as follows:

*

The electronic specific heat constant, g, and the

magnetic susceptibility, w, are much larger than those

corresponding to normal magnetic behavior, but the

Wilson ratio, R ¼g/w, remains constant between 1

and 2 in suitable units. The values of g are typically of

the order of 1000 mJmol

1

K

2

in the case of com-

pounds that remain nonmagnetic at low temperatures

and of the order of 100 mJmol

1

K

2

in the case of

compounds which order magnetically. The term

‘‘heavy fermions’’ originates from these high values

of g and w, and Table 1 gives some examples of heavy-

fermion systems (see Heavy-fermion Systems).

*

Direct evidence of the heavy-fermion behavior

has been obtained by de Haas van Alphen effect ex-

periments in many Cerium compounds, such as

CeCu

6

, CeB

6

, and CeRu

2

Si

2

, and some uranium

compounds. An effective mass up to roughly 100m

e

(where m

e

is the electron mass) has been observed in

cerium compounds (Onuki and Hasegawa 1995).

*

The transport properties of cerium Kondo com-

pounds are described by the Fermi liquid forma-

lism at low temperatures. In particular, the electrical

resistivity follows a T

2

law and the coefficient, A,

of this term is particularly large in heavy-fermion

systems.

The exchange Hamiltonian (Eqn. (3)) describes

well the case of a magnetic impurity embedded in a

normal matrix. The Anderson Hamiltonian (Eqn. (2))

is in fact richer, because it can describe different sit-

uations, such as the nonmagnetic and the magnetic

case or the intermediate valence (see Intermediate

Valence Systems) and the almost integer valence.

However, in the special case of a magnetic impurity

with a valence close to an integer (3 in the cerium

case), Schrieffer and Wolff (1966) have shown that

the Anderson Hamiltonian is equivalent to a Kondo

Hamiltonian with a J value given by

J ¼

7V

kf

7

2

7E

0

E

F

7

ð6Þ

and we immediately see that the J value is negative.

Thus, this so-called Schrieffer–Wolff transformation

allows one to show that the Anderson Hamiltonian in

the almost ionic limit yields automatically a negative

J value and, therefore, the Kondo effect.

Table 1

Some examples of heavy-fermion compounds.

Compound Crystal structure (ground state) CEF splitting (K) T

N

(K) g (mJmol

K

2

)

CeAl

3

Hexagonal 60–90 1600

CeCu

2

Si

2

Tetragonal 140–360 1000

CeCu

6

Orthorhombic 100–240 1500

CeRu

2

Si

2

Tetragonal 220 350

CeInCu

2

Cubic (G

7

) 90 1200

CeCu

4

Ga Hexagonal 100 1800

CeAl

2

Cubic (G

7

) 100 3.85 135

CeB

6

Cubic (G

8

) 500 3.2 300

CeRh

2

Si

2

Tetragonal 150 36 23

Ce

3

Al

11

Orthorhombic 100 T

c

¼6.2 (Ferro) 120

CeIn

3

Cubic (G

7

) 100 10 140

CeAl

2

Ga

2

Tetragonal 66–122 8.5 80

CeCu

2

Orthorhombic 200 3.5 82

CeCu

2

Ge

2

Tetragonal 200 4.15 100

Ce

2

Sn

5

Orthorhombic 70–155 2.9 380

YbCu

4

Ag Cubic 45 245

YbBiPt Cubic 8000

YbNi

2

B

2

C Tetragonal 40–200 530

YbCu

2

Si

2

Tetragonal 216 135

YbNiAl Hexagonal 35 2.9 350

U(Pt

0.95

Pd

0.05

)

3

Hexagonal 6 500

UPd

2

Al

3

Hexagonal 14.3 150

UNi

2

Al

3

Hexagonal 4.6 120

NpSn

3

Cubic 9.5 240

YMn

2

Cubic 100 160

LiV

2

O

4

Cubic 400

139

Electron Systems: Strong Correlations