Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Liu Z, Richter M, Divis

ˇ

M, Eschrig H 1999 Calcula-

tion of paramagnetic susceptibilities and specific heats by

density-functional-crystal-field theory: PrPd

2

X

3

and

NdPd

2

X

3

(X ¼Al, Ga). Phys. Rev. B 60, 7981–92

Liu Z S, Park J G, Kwon Y S, McEwen K A, Bull M J 2003

Crystal-field excitations and model calculations of CeTe

2

. J.

Magn. Magn. Mater. 256, 151–7

Martinho H, Sanjurjo J A, Rettori C, Canfield P C, Pagliuso P

G 2001 Raman scattering study of crystal field excitations in

ErNi

2

B

2

C. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 226–230, 978–9

Moze O 1998 Crystal field effects in intermetallic compounds

studied by inelastic neutron scattering. In: Buschow K H J

(ed.). Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 11, pp. 493–624

Moze O, Buschow K H J 1996 Magnetic structure of

ErCo

12

Mo

2

and TbCo

12

Mo

2

determined by time-of-flight

neutron diffraction. Z. Phys. B 101, 521–6

Moze O, Rosenkranz S, Osborn R, Buschow K H J 2000 Mag-

netic excitations in tetragonal HoCr

2

Si

2

. J. Appl. Phys. 87,

6283–5

Rudowicz C 1987 On the derivation of the superposition-model

formulae using the transformation relations for the Stevens

operators. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 20, 6033–6037

Sierks C, Loewenhaupt M, Freudenberger J, Mu

¨

ller K-H,

Schober H 2000 Magnetic excitations in TM

0.05

Y

0.95

Ni

2

11

B

2

C. Physica B 276–278, 630–1–6033

Stra

¨

ssle Th, Altorfer F, Furrer A 2001 Crystal-field interactions

in the pseudo-ternary compound in ErAl

x

Ga

2x

studied by

inelastic neutron scattering. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 13,

6773–85

Stra

¨

ssle Th, Divis

ˇ

M, Rusz J, Janssen S, Juranji F, Sadykov R,

Furrer A 2003 Crystal-field excitations in PrAl

3

and NdAl

3

at

ambient and elevated pressure. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15,

3257–66

Takegahara K 2000 Matrix elements of crystal electric fields in

rare-earth compounds. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 69 (5), 1572–3

Takegahara K, Hisatomo H, Yanase A 2001 Crystal electric

fields for cubic point groups. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 70 (5),

1190–3

Wang Y-L 1971 Crystal-field effects of paramagnetic Curie

temperature. Phys. Lett. A 35, 383–4

O. Moze

Modena University, Italy

100

Crystal Fie ld Effects in Intermetallic Compounds: Inelastic Neutron Scattering Results

Demagnetization: Nuclear and Adiabatic

1. Principles of the M ethod

Adiabatic demagnetization (AD) is one of the cool-

ing methods that have a common principle: the

entropy of the working medium (helium, spins, etc.)

is controlled by some parameter like pressure or

magnetic field. The working medium in AD is a

system of magnetic moments (nuclear spins, electronic

spins, or orbital moments) and the magnetic field is

the control parameter when the magnetocaloric effect

is employed. The magnetization, M, of a paramagnet

or a ferromagnet increases with an applied magne-

tic field, H, and simultaneously both the energy of

magnetic moments in the field and the internal energy

of their exchange interaction decrease. Supposing

negligible pressure and volume effects, the entropy

can be expressed by the following thermodynamic

relation:

dS ¼

1

T

@U

@T

H

dT þ

1

T

@U

@H

T

þM

dH ð1Þ

The internal energy, U, is a function of the

temperature, T, of the sample, and in general it

increases with temperature. Consequently, if the

magnetization of a paramagnetic sample is reduced

adiabatically, the sample temperature should de-

crease. The cooling cycle of the AD method consist

of two steps:

(i) Isothermal magnetization. The sample is in

thermal contact with a constant temperature bath

kept at T

i

. The magnetic field is increased from zero

to H

i

and the heat released to the bath compensates

for the work done on the sample. It leads to an

increase in the order of the magnetic moments and,

consequently, reducing their entropy, S,by

DS ¼

Z

H

0

@M

@T

H

dH ð2Þ

This entropy change is determined by the rate of

change of magnetic energy with respect to the thermal

energy. The efficiency of the process increases with

decreasing temperature.

(ii) Adiabatic demagnetization. The sample is ther-

mally isolated from the bath, and the field is then

reduced from H

i

to H

f

. It is an adiabatic process, i.e.,

dQ ¼TdS ¼0 and the entropy remains constant.

Since the sample performs magnetic work by demag-

netizing at the expense of internal energy, it decreases

in temperature towards T

f

at a rate given by:

dT

ðdS¼0Þ

¼

T

@M

@T

H

C

H

dH ð3Þ

where C

H

is the specific heat.

AD is a one-shut process. After demagnetization

the system will warm up owing to a parasitic heat

load. The energy which can be absorbed, Q ¼

R

Tds,

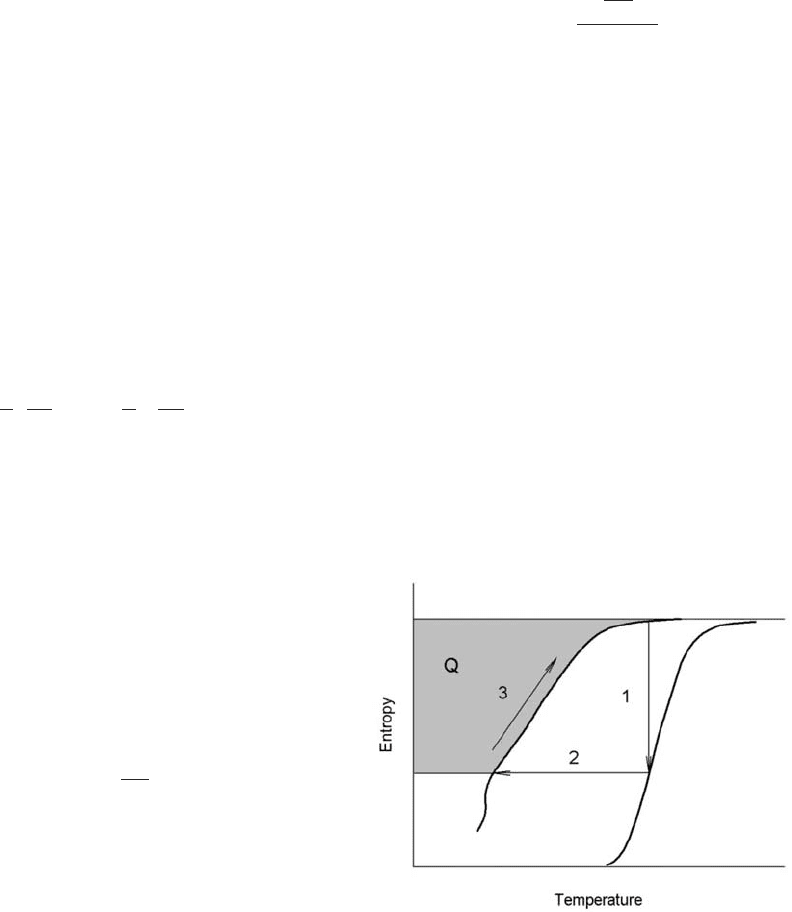

is proportional to the shaded area in Fig. 1.

In modeling a system of noninteracting moments,

m, the entropy is simply a function of H/T. For an

isoentropic process T

f

¼T

i

H

f

/H

i

and absolute zero

temperature could be reached for H

f

¼0, in contra-

diction to the third law of thermodynamics. This does

not happen in a real system, however, because the

assumption of noninteracting spins breaks down

and the energy levels in zero applied field are not

degenerate. The lowest temperature achievable by the

AD method is limited by the existence of an internal

interaction in a spin system. This interaction causes

spin ordering at sufficiently low temperatures and a

spontaneous decrease of the entropy of a system. The

detailed nature of the interactions may be compli-

cated. It may be, for example, the direct dipolar

interaction between magnetic moments in the case of

dielectrics or the RKKY interaction in metals. It

simplifies matters to define an effective internal field,

Figure 1

Graphical representation of the processes of isothermal

magnetization (1) and adiabatic demagnetization (2).

The shaded area shows the cooling power during a warm

up (3).

D

101

h, such that it would produce a Zeeman splitting

equal to the splitting, e, due to the interaction, i.e.,

e ¼mm

0

h. Then:

T

f

¼ T

i

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

H

2

f

þ h

2

H

2

i

þ h

2

s

ð4Þ

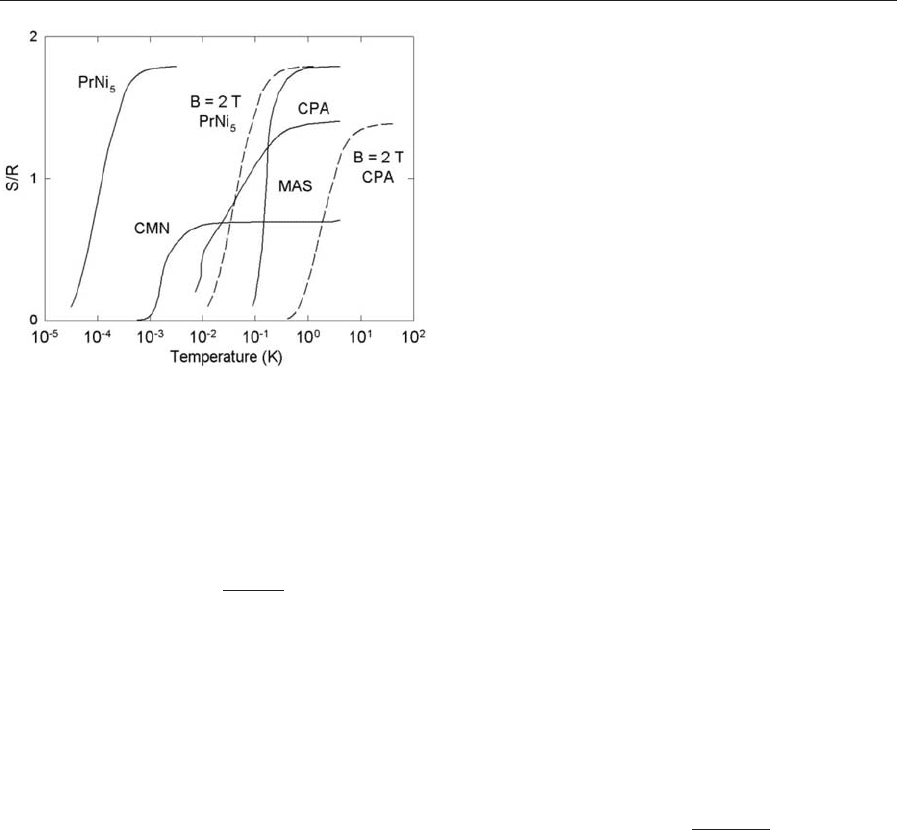

The temperature dependence of the entropy of

some substances used for this cooling method is

shown in Fig. 2.

2. Practical Aspects

The most common substances used for the AD

method are paramagnetic salts such as MAS ¼

Mn

2 þ

SO

4

(NH

4

)

2

SO

4

.6H

2

O(T

c

E0.17 K; bE80 mT),

FAA ¼Fe

3þ

2

(SO

4

)

3

(NH

4

)

2

SO

4

.24H

2

O (0.03 K; 50 mT),

CPA ¼Cr

3þ

2

(SO

4

)

3

K

2

SO

4

.24H

2

O (0.01K; 10 mT),

CMN ¼2Ce

3 þ

(NO

3

)

3

3Mg(NO

3

)

2

.24H

2

O (0.002K;

4mT), Gd

2

(SO

4

)

3

.8H

2

O (0.18 K), van Vleck para-

magnets such as PrNi

5

(0.0004 K; 16 mT) and PrCu

6

(0.0026 K), and pure metals such as copper (58 nK;

0.3 mT) and silver (0.56 nK). The ordering tempera-

ture and the effective internal field are given in

parentheses.

Besides cooling magnetic moments by AD, for any

practical use it is also necessary to cool the lattice of

which the magnetic atoms form a part. The exchange

of energy between the spins and the lattice is

characterized by the spin–lattice relaxation time, t

1

.

For metals the exchange is mediated by the conduction

electrons and t

1

is given by the Korringa relation. In

nonmetals, owing to their poor thermal conductivity,

t

1

can reach hours or days at very low temperatures.

The use of the magnetocaloric effect to produce

temperatures well below 1 K was proposed by

Giauque and Debye in 1926. A practical realization

of AD cooling was announced in 1933 by Giauque

and MacDougall, reaching 0.53 K using Gd

2

(SO

4

)

3

.

8H

2

O at starting conditions of 3.4 K and 0.8 T. On

the other hand, de Haas, Wiersma, Kramers used

CeF

2

, and after demagnetization from 3 T to 0.1 T

decreased the temperature from 1.26 K to 0.27 K.

According to present knowledge, 0.001 K is the

estimated lower limit achievable by the AD technique

employing electronic paramagnetism.

In 1934 Gorter proposed nuclear magnetic refrig-

eration but owing to severe experimental problems it

was only in 1956 that Kurti succeeded in reducing the

nuclear spin temperature in copper wires to about

20 mK. Osgood and Goodking in 1966 were the first

to achieve considerable electron and lattice refrigera-

tion. The progress made in the AD technique enabled

the Helsinki group, in 1982, to observe spontaneous

nuclear order of copper below the Ne

´

el temperature

T

N

¼58 nK (Oja and Lounasmaa 1997). The nuclear

order in silver with T

N

¼560 pK has been investi-

gated and the long spin–spin relaxation time of silver

made it possible to produce a negative nuclear spin

temperature and to find ferromagnetic order in silver

above T

C

¼1.9 nK (Oja and Lounasmaa 1997). The

lowest temperature achieved is 280 pK and 750 pK

is the highest temperature obtained (Oja and

Lounasmaa 1997).

Using the known potential of van Vleck para-

magnets for nuclear refrigeration, Andres and

Lounasmaa (1982) tested many of them. The

electronic ground states of van Vleck paramagnets

are nonmagnetic singlets. Owing to the nuclear

hyperfine interaction of nuclear and electronic spins

a magnetic moment is induced into the ground state.

This can be formally described by assuming that the

nuclear magnetic moment is enhanced by a factor

1 þ K 1 þ

Aw

VV

g

J

m

B

g

N

m

N

ð5Þ

where A is the hyperfine interaction constant and w

VV

the van Vleck temperature-independent susceptibility.

For Pr or Tm compounds, K is typically 10–100. PrNi

5

(hyperfine interaction-enhanced nuclear ferromagnet,

T

C

¼0.4 mK) or PrCu

6

(T

N

¼2.6 mK) serve in a lower

stage in many nuclear refrigerators. The starting con-

ditions for demagnetization, B/TE500–1000 TK

1

,

are fulfilled by available dilution refrigerators and

superconducting magnets. Advantages of these mate-

rials are a huge cooling power and a short t

1

.

3. Outlook

AD is mostly used in the temperature range below

1 mK but its ability to work in zero gravity has led

to the development of prototypes for satellite

Figure 2

Entropies per mole of substance, S /R, of four salts and

PrNi

5

in zero field (solid curves) and in a 2 T field

(dashed curves).

102

Demagnetization: Nuclear and Adiabatic

applications. It is a prospective method as AD can

reach higher efficiency than traditional vapor com-

pression technology. To apply this method to a wide

temperature range up to room temperature, con-

siderable progress in materials research is needed.

Materials with a large magnetocaloric effect are

fundamental for AD but they are also suitable for

regenerators in other types of refrigerators. For

devices suitable for cooling at room temperature

(see Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to Practice).

See also: Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Tempera-

ture

Bibliography

Andres K, Lounasmaa O V 1982 Recent progress in nuclear

cooling. In: Brewer D F (ed.) Progress in Low-Temperature

Physics. North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 8, pp. 222–87

Betts D S 1976 Refrigeration and Thermometry Below One

Kelvin. Sussex University Press, Brighton, UK

Hagmann C, Richards P L 1995 Adiabatic demagnetization

refrigerators for small laboratory experiments and space

astronomy. Cryogenics 35, 303–9

Hudson R P 1972 Principles and Application of Magnetic

Cooling North-Holland, Amsterdam

Oja A S, Lounasmaa O V 1997 Nuclear magnetic ordering in

simple metals at positive and negative nanokelvin tempera-

tures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 1–136

Pecharsky V K, Gschneidner K A Jr. 1999 Magnetocaloric

effect and magnetic refrigeration. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.

200, 44–56

Pobell F 1992 Matter and Methods at Low Temperatures.

Springer, Berlin

J. Sebek

Institute of Physics ASCR, Prague, Czech Republic

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism

Spin density functional theory (SDFT) is the basis of

most of the modern electronic structure calculations.

It has been reviewed in detail by Jones and Gun-

narsson (1989), Trickey (1990), Eschrig (1996), and

many others, and is only briefly outlined here.

1. Spin Density Functional Theory

1.1 General Theory

At the quantum mechanical level, magnetic properties

of materials are usually well described within the Born–

Oppenheimer (adiabatic) approximation: the electrons,

moving much faster than the heavier atomic nuclei,

are considered in the Coulomb potential v(r) ¼

P

s

Z

s

/

7rR

s

7 created by the nuclei of charge Z

s

in their

instantaneous positions R

s

. In most cases, the values of

R

s

are approximated by the rest positions of the atoms

in a regular structure.

For each set of {R

s

} there is a state of the electrons

with the lowest energy, the ground state 7c

0

S. Its

energy can be written as a functional of the potential,

E

0

[v], i.e., the ground state energy depends on the

Coulomb potential of the nuclei at each point r of

space. The exact functional dependence E

0

[v]isin

general unknown, but reasonable approximations

will be discussed below. They allow for a determina-

tion of the atomic rest positions in molecules and

solids with an accuracy of a few percent, by minimi-

zation of the energy [E

0

þ

P

ss

0

Z

s

Z

s

0

/7R

s

R

s

0

7] with

respect to {R

s

} (Moruzzi et al. 1978).

The calculation of observable quantities from the

true wave function c

0

is not feasible in the case of

many, strongly interacting electrons, since c

0

de-

pends on the coordinates r

i

and on the spin quantum

numbers s

i

of all N electrons, although the total en-

ergy may be expressed in terms of the spin and pair

densities. Hohenberg and Kohn (1964) went further

and proved that the ground state density function

n

0

(r) alone determines v(r) and hence c

0,

together

with all ground state properties uniquely. Since the

ground state spin density matrix n

0

(r)

n

0

ðrÞ¼n

0;ss

0

ðrÞ

¼ N

X

s

2

Z

d

3

r

2

y

X

s

N

Z

d

3

r

N

c

0

ðr; s; r

2

; s

2

; y; s

N

Þ

c

0

ðr; s

0

; r

2

; s

2

; y; s

N

Þð1Þ

comprises the information on the electron density,

n ¼trn, the unique determination of the ground state

by the spin density follows as a corollary. It allows, as

an important generalization, the inclusion of the ac-

tion of an external magnetic field B on the spin, by

the definition of the spin-dependent external poten-

tial v ¼v þm

B

rB. Here, r ¼(s

x

, s

y

, s

z

) denote the

Pauli spin matrices. The vector spin density is given

as R ¼tr(rn). Further, the total spin in a given vol-

ume V is S ¼

R

V

d

3

r R/2, and the related spin magnetic

moment is defined by l

s

¼m

B

2S.

The calculation of E

0

and n

0

becomes possible

with the help of the Hohenberg–Kohn variational

principle:

E

0

½v¼min

c

/c7

#

H7cS

¼ min

n

Z

d

3

rtrðvnÞþmin

c

n

/c

n

7

#

T þ

#

U7c

n

S

R

d

3

rn¼N

ð2Þ

where c

n

means the class of all normalized fermionic

wave functions with the spin density n. The electronic

103

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism

Hamiltonian H

ˆ

consists of the potential v plus the

operators of the kinetic energy, T

ˆ

, and of the elec-

tron–electron interaction energy, U

ˆ

. The latter terms

are further subdivided (Kohn and Sham 1965):

min

c

n

/c

n

7

#

T þ

#

U7c

n

S ¼ T

s

½nþE

H

½nþE

xc

½nð3Þ

Here, T

s

is the ground state kinetic energy of a

model system of electrons that are assumed to have

no mutual Coulomb interaction and to possess the

spin density matrix n:

T

s

½n¼

X

N

i

X

s

/f

i

ðsÞ7 D=27f

i

ðsÞS;

d

ij

¼

X

s

/f

i

ðsÞ7f

j

ðsÞS ð4Þ

n

ss

0

¼

X

N

i

f

i

ðsÞf

i

ðs

0

Þð5Þ

The f

i

denote the N lowest single-particle eigenstates

in a corresponding, yet unknown, effective potential.

Further, E

H

is the spin-independent Hartree energy:

E

H

¼

1

2

ZZ

d

3

rd

3

r

0

nðrÞnðr

0

Þ

7r r

0

7

ð6Þ

and E

xc

[n], the so-called exchange-correlation (xc)

energy, is an unknown functional of the spin density

matrix, containing all contributions beyond the mean

field approximation from electron–electron interac-

tions in the ground state.

The essence of the Kohn–Sham procedure is to

subdivide the total energy into large contributions

that are either well-known functionals (

R

d

3

r tr(vn)

and E

H

), or at least computable quantities (T

s

), and a

much smaller remaining part (E

xc

). Then, approxi-

mations applied to the latter part are expected to in-

troduce only reasonably small errors. However, all

known approximations to E

xc

are unfortunately on

a heuristic level and cannot be systematically im-

proved. Thus, the spin density functional theory

(SDFT) described here and in the following has to be

considered as a model theory, in the sense that the

applicability of any chosen approximation is justified

a posteriori by experience from comparison with ex-

periment. On the other hand, within a given approx-

imation, the calculations are usually carried out

without adjustable parameters. In this way, after val-

idating the approximation for a certain class of ma-

terials, reliable forecasts of experimental results on

this class can be expected from theory.

For this aim, a numerically tractable formulation is

needed to allow for the calculation of n

0

and E

0

. Such

a formulation is given by the Kohn–Sham equations

that are obtained by: (i) inserting Eqn. (3) in Eqn. (2),

(ii) using the Ansatz Eqn. (5) also in the case with

electron–electron interaction, and (iii) varying with

respect to the f

*

i

:

X

s

0

D

2

d

ss

0

þ v

eff;ss

0

f

i

ðs

0

Þ¼e

i

f

i

ðsÞð7Þ

The Kohn–Sham equations (Eqn. (7)) contain the

above-mentioned effective potential:

v

eff;ss

0

¼ v

ss

0

ðrÞþ

Z

d

3

r

0

nðr

0

Þ

7r r

0

7

d

ss

0

þ v

xc;ss

0

ð8Þ

consisting of external, Hartree, and xc potentials. The

latter is defined by: v

xc;ss

0

¼ dE

xc

½n=dn

ss

0

.

Together with Eqn. (5), these equations form a

nonlinear system of integro-differential equations

which have to be solved by iteration (self-consistent

solution). Due to the complexity of the Kohn–Sham

equations (reflecting part of the complexity of na-

ture), more than one stationary solution may exist.

The further solutions can be related to physically

relevant metastable magnetic states (for instance,

low-spin/high-spin states, see Sect. 3.3, or different

magnetic moment arrangements). This problem is in-

vestigated in some detail by Moruzzi and Marcus

(1993).

1.2 Approximations

The most widely used approximation for E

xc

[n] is the

local spin density approximation (LSDA):

E

xc

½nEE

LSDA

xc

½n¼

Z

d

3

rnðrÞe

hom

xc

n

m

ðrÞ; n

k

ðrÞ

ð9Þ

Here, e

hom

xc

means the exchange-correlation energy per

electron of the spin-polarized homogeneous electron

gas, a model system frequently used in electronic

structure theory. The quantities n

m

and n

k

denote

spin-up and spin-down densities. They are obtained

by rotating the spin quantization axis at each point in

space in the direction that yields a diagonal spin

density matrix.

Another, more recent, approximation is called the

generalized gradient approximation (GGA). At var-

iance with the LSDA, it takes into account not only

the local value of n, but also its spatial derivatives.

If electrons in one of the open shells do not con-

tribute to the chemical bonding, like 4f states in most

rare-earth systems, they should be distinguished from

the valence electrons in the theoretical treatment as

well. Then, the so-called open-core approximation, or

the self-interaction-corrected (SIC) LSDA, are mod-

ern approximations to be used (Richter 1998). The

latter approximation is also relevant to finite systems

like atoms and small molecules.

The energy e

hom

xc

can be subdivided into e

hom

xc

¼

e

hom

x

þe

hom

c

. Here, e

hom

x

describes the effect of ex-

change interaction: according to the Pauli exclusion

104

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism

principle, electrons with the same spin quantum

number should have a zero probability density of

being at the same point in space. For this reason, the

Coulomb energy between pairs of electrons with the

same spin is lower than between pairs with different

spin, and e

hom

x

o0. The energy e

hom

c

describes the ef-

fect of Coulomb correlation: electrons with arbitrary

spin do not move in a stochastic way either, but tend

to avoid each other due to their mutual Coulomb

repulsion. This correlated motion yields a smaller to-

tal energy than estimated by a mean field treatment,

and e

hom

c

o0 holds as well.

1.3 Hund’s Rules

In atoms, exchange interaction is the reason for in-

completely filled shells to maximize their spin polar-

ization (SP) in the ground state. This behavior is

known as Hund’s First Rule (see Magnetism in Sol-

ids: General Introduction). It is driven by an energy

gain E

SP

BS(S1/2) in comparison to an unpolarized

shell (Melsen et al. 1994), where the total spin S is

zero. If LSDA is applied to an atom, then

E

SP

EDE

xc

¼E

LSDA

xc

(S)E

LSDA

xc

(0)EIS

2

, yielding a

good approximation for the relation above in the case

of large total spins. This fact indicates that LSDA is

particularly suited for extended systems which are

closer to the idealized homogeneous electron gas

than atoms are. The prefactor I is called the Stoner

parameter.

While free atoms in their ground state always carry

a maximum spin moment, this is not the case in con-

densed matter. The reason for this difference is that

band splitting lifts the degeneracy of the atomic

states. As a consequence, energy is gained when the

spin polarization is reduced, since then states at the

majority spin Fermi surface with a higher Fermi mo-

mentum are emptied in favor of states at the minority

spin Fermi surface with a lower Fermi momentum.

The energy gain DT

s

is the bigger the broader the

band is, and vanishes in the atomic limit.

This consideration is the essence of Stoner theory

(see Itinerant Electron Systems: Magnetism (Ferro-

magnetism)), which evaluates the counterbalance of

DE

xc

and DT

s

to give a criterion for the onset of long-

range spin order when starting from a spin-compen-

sated state. The condition for the instability of the

Pauli paramagnetic state is that:

INðE

F

Þ41 ð10Þ

where N(E

F

) denotes the density of states at the Fer-

mi energy for one spin direction. Detailed discussion

of the first-principles investigation of the magnetic

ordering is given in Sect. 2.

Orbital magnetism also plays a big role in solids,

e.g., for the phenomenon of magnetocrystalline an-

isotropy. It arises if the other two of Hund’s rules are

considered. Hund’s Second Rule states that of all

atomic terms with maximum spin, the term with the

largest total angular momentum L is the lowest in

energy. The related energy gain is called orbital po-

larization (OP) energy, E

OP

, which vanishes for s- and

p-shells. Coulomb correlation is the reason behind

OP. Though the LSDA accounts for a part of

Coulomb correlation contributions, OP cannot be

obtained in a local approximation, since any defini-

tion of an angular momentum density is ambiguous,

due to the gauge freedom of this quantity. Reason-

able heuristic approximations, called OP corrections,

(Eriksson et al. 1989) use the local gauge where the

angular momentum density vanishes in the interstitial

regions. The angular momenta of the individual

atomic shells are assumed to give contributions to

the xc energy of the form E

OP

EE

xc

(L)E

xc

(0) ¼

const.

.

L

2

o0, resembling the form of the SP term.

Finally, Hund’s Third Rule determines the cou-

pling between spin and orbital degrees of freedom to

be antiparallel or parallel in the ground state of less

or more than half-filled atomic shells, respectively.

This behavior is a relativistic effect: the fast-moving

electrons experience a magnetic field generated by the

relative motion of the nuclear charges with respect to

the rest system of the electrons. This field interacts

with the individual electron spins and yields an ad-

ditional contribution to the kinetic energy of the

form: E

SO

¼

P

i

x

i

/s

i

l

i

S

i

, where x

i

are radial inte-

grals called spin-orbit coupling (SOC) constants, and

l

i

are single-particle angular momentum operators.

The important role of SOC in solid state magnetism

is discussed in more detail in Sects. 2 and 3.

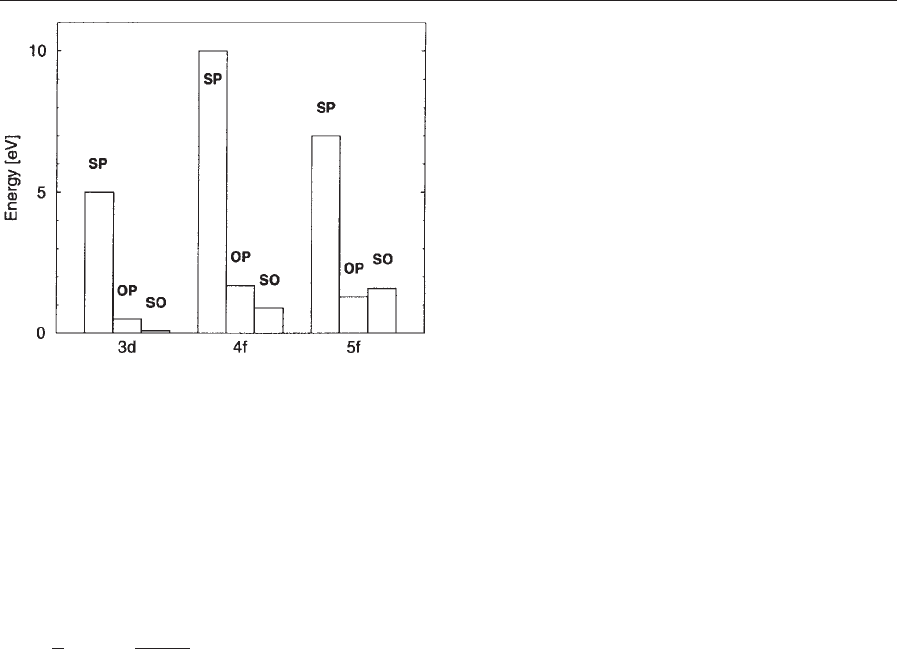

Figure 1 shows the range of energies related to

Hund’s rules couplings in those atomic shells that are

most important in solid-state magnetism: transition

metal 3d, rare-earth 4f, and actinide 5f shells. The

spin polarization energy, E

SP

, is maximum for half-

filled shells, while the orbital polarization energy,

E

OP

, and the spin–orbit coupling energy, E

SO

, are

large for shell fillings close to 1/4 and 3/4. In metals

and compounds, spin and orbital polarization energy

can be much smaller, or even zero, since losses of T

s

and E

H

due to polarization compensate at least part

of the polarization gains: for instance, E

SP

E0.4 eV

in iron metal. In general, the atomic values given in

Fig. 1 put an upper boundary on the energy scales

observed in solids.

1.4 Single Particle Excitations

The Kohn–Sham orbitals f

i

, with related single-

particle energies e

i

, have been introduced above as

auxiliary quantities needed to compute the spin den-

sity matrix. In a hypothetical system without elec-

tron–electron interaction, these Kohn–Sham states

would coincide with the quasi-particle excitations of

the system, which can be probed by optical, x-ray or

electron spectroscopies (Sections 3.4 and 3.5). To

105

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism

evaluate single-electron or single-hole excitations c

i

close to the Fermi level of a realistic system, the

Dyson equation:

D

2

þ

Z

d

3

r

0

nðr

0

Þ

7r r

0

7

c

i

ðs; rÞ

þ

X

s

0

v

ss

0

þ

Z

d

3

r

0

M

ss

0

ðr; r

0

; E

i

Þ

c

i

ðs

0

; r

0

Þ

¼ E

i

c

i

ðs; rÞð11Þ

has to be solved. However, full knowledge of the self-

energy operator kernel M is even further away than

full knowledge of v

xc

; both quantities must rather

be approximated on the basis of physical intuition.

As a matter of fact, the replacement of M

ss

0

by

d(rr

0

)v

xc,ss

0

(n), i.e., the LSDA, turns out to work

fairly well for many systems (weakly correlated sys-

tems). In particular, the spectra related to s and p

valence states of simple and transition metals, as

well as rare-earth 5d and actinide 6d states, are well

described.

These states form broad bands; the quasi-particle is

extended over many atoms due to the large hopping

rate, and thus correlation effects are small. If the

bands become narrower, the hopping rate is lower,

and hence a stronger intra-atomic Coulomb repul-

sion/attraction is felt by additional electrons/holes.

Strong on-site correlations result in a jump of M,asa

function of energy, at the Fermi level E

F

by an

amount U

eff

. This quantity is related to the on-site

Coulomb matrix element U, but is strongly screened

in metals. A simple approximation for this situation

is called LSDA þU, where the energy dependence of

M is reduced to the jump at E

F

and otherwise the

LSDA is used. A certain problem in this approach is

that the screening depends much on chemical com-

position and on local structure, such that the value of

U

eff

is not just an atomic property as U is; it has to be

estimated for each individual situation.

Finally, the relationship between U

eff

and the band

width W determines if the related states contribute to

the chemical bonding or not. Accordingly, these

states may exhibit itinerant or localized magnetic

behavior. The rare-earth 4f shells where U

eff

bW

show local moment behavior in most cases. On the

other hand, elemental 3d metals (U

eff

oW) are itine-

rant magnets. Actinide systems as well as transition

metal compounds may show both types of behavior.

1.5 Model Parameters

Model parameters like U

eff

may be obtained by

means of constrained SDFT calculations (Dederichs

et al. 1984). The general idea behind this method is to

impose a symmetry restriction on the considered sys-

tem that models, in a static way, a certain quasi-

particle excitation. If the time-scales of the excitation

and of the remaining degrees of freedom are different

enough, the response of the latter, treated in a self-

consistent calculation, provides a fairly realistic de-

scription of the screening process (Gunnarsson 1990).

Prominent examples are so-called frozen magnon

calculations, where the atomic spin directions are

fixed to form a periodic wave. Then, the ground-state

energy is calculated for both the relaxed and the

constrained system, and the energy difference is

equated with the related excitation energy. Heisenb-

erg model parameters describing the interatomic ex-

change coupling may be fitted to frozen magnon

spectra or to other constrained magnetic configura-

tions. They are used to describe thermodynamic

properties of magnetic substances.

Finally, crystal field model parameters should be

mentioned. They enter model theories for the de-

scription of magnetism related to localized 4f states

(see Localized 4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism). The

parameters may be obtained by applying shape re-

strictions on the atomic 4f charge density (Brooks

et al. 1997, Richter 1998).

2. Magnetic Orde ring

One of the major tasks of the SDFT is the first-prin-

ciples description of the ground-state magnetic order.

There is a great variety of possible magnetic ground

states, for example: Pauli paramagnetism in vanadi-

um, ferromagnetism in nickel, antiferromagnetism in

chromium, spiral magnetic structures in g-iron and

rare-earth metals, complex noncollinear magnetic

Figure 1

Range of energies related to Hund’s rules in atoms:

transition metal 3d shells, rare-earth 4f shells, and

actinide 5f shells. The labels SP, OP, and SO denote the

maximum values, within the related shell, of the energies

E

SP

, E

OP

, and E

SO

(Hund’s First, Second, and Third

Rule coupling energies, respectively).

106

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism

structures in compounds of the transition metals and

actinides, and disordered magnetic state in amor-

phous iron. In principle, the machinery of the SDFT

allows one to start with an arbitrary magnetization

and, by calculating to self-consistency, to determine

the ground state magnetization. However, in this

general approach the study of even the simplest mag-

netic system becomes a complex computational prob-

lem. This kind of calculation is unavoidable for the

systems with no regular magnetic structure, but oth-

erwise available experimental and theoretical infor-

mation about the magnetic ground state is usually

used to simplify calculations.

According to its basic theorems (Sect. 1.1), the

SDFT supplies physical information about the state

of the system which realizes the minimum of the en-

ergy-functional. The applications of the theory can,

however, be extended by the possibility of the con-

strained calculations, where the process of minimiza-

tion takes place under certain restricting conditions

(Dederichs et al. 1984) imposed upon, for example,

the symmetry of the magnetic density and effective

potential.

An important example of the constraint is the con-

straint of zero magnetisation: m(r) ¼0 for any r. Even

for magnetic systems, it is possible to calculate the

lowest energy nonmagnetic state and to study the

physical reasons for the instability of this state with

respect to the formation of the magnetic structure

(see Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction).

2.1 Ferromagnetic Structure

The best-studied magnetic crystals are the elementary

3d metals with ferromagnetic magnetic ordering: a-

iron (iron with the body-centered cubic lattice), co-

balt, and nickel. The instability of the nonmagnetic

state of a 3d metal with respect to the formation of a

ferromagnetic structure can be studied with the help

of the Stoner criterion, Eqn. (10). The density of

states (DOS) of the nonmagnetic a-iron is shown in

Itinerant Electron Systems: Magnetism (Ferromag-

netism) (Fig. 3). The DOS has a peak at the position

of the Fermi level that indicates the instability of the

nonmagnetic state. Indeed, if the constraint of zero

magnetization is removed by placing a small mag-

netic moment at each iron site, the calculation results

in the ferromagnetic state with the atomic magnetic

moment which is close to the observed value (e.g.,

2.15 m

B

in the calculation of Moruzzi et al. (1978)).

One obtains a similar situation in cobalt and nickel

(Moruzzi et al. 1978).

2.2 Antiferromagnetic Structure

For chromium, the Stoner product is less than 1. Still

the nonmagnetic state of chromium is unstable, but

in this case with respect to the formation of an

antiferromagnetic structure. The antiferromagnetic

structure can be treated as a magnetic structure with

the spatial variation of the atomic magnetic moments

defined by the wave vector q ¼

1

2

K, where K is a

vector of the reciprocal lattice. The Stoner criterion

generalized to the case of the magnetic structures

characterized by an arbitrary value of q takes the

form:

IwðqÞ41 ð12Þ

where w(q) is the unenhanced magnetic susceptibility

of the nonmagnetic state of the system in a non-

uniform static magnetic field, with spatial variation

defined by vector q. For a ferromagnet, q ¼0 and the

susceptibility is equal to the density of states at the

Fermi level.

For a finite q, the susceptibility is given by the

formula:

wðqÞ¼

X

knm

f ðe

nk

Þf ðe

mkq

Þ

e

mkq

e

nk

þ id

/kn e

iqr

k qmS

ð13Þ

and cannot be expressed through the DOS. Here, n

and m are band indices, d is an infinitesimal, and f(e)is

the Fermi–Dirac distribution function.

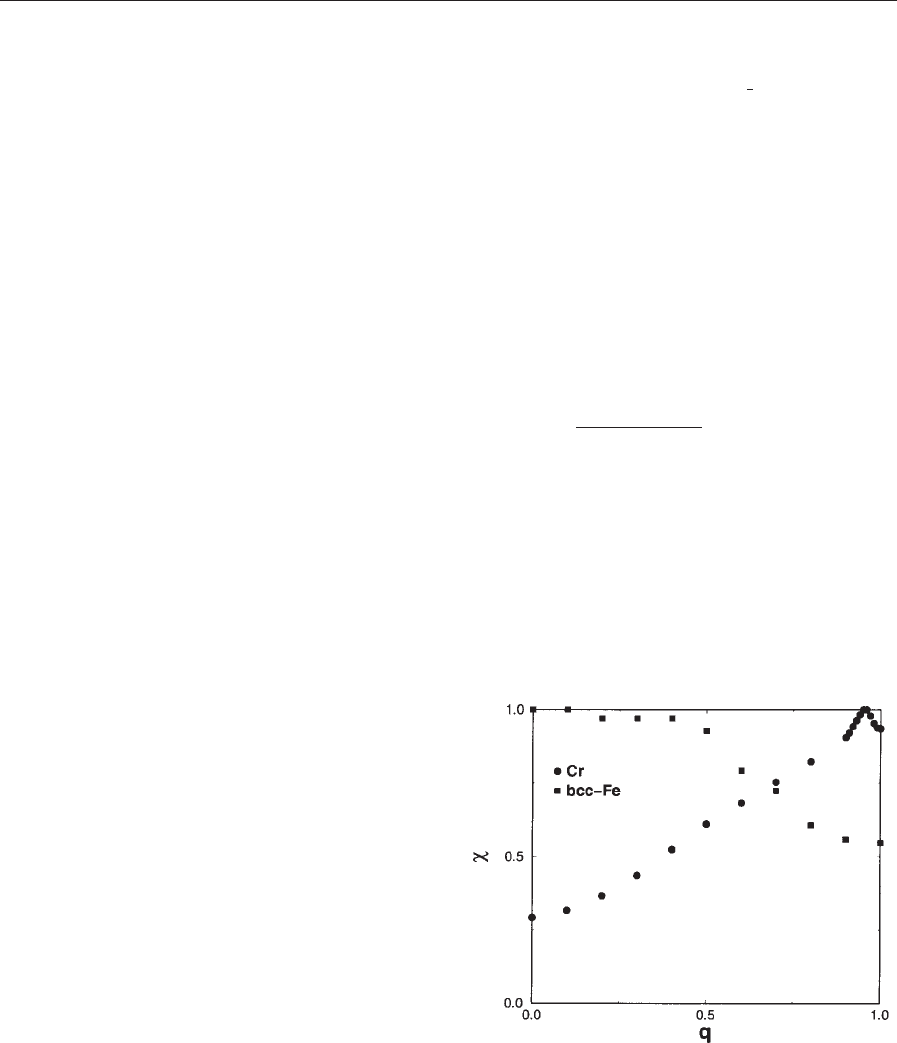

In Fig. 2, we compare the calculated q-dependences

of the susceptibility of a-iron and chromium. The two

curves are essentially different. In the case of a-iron,

the susceptibility is maximum for q ¼0 and decreases

monotonically with increasing q, clearly revealing the

origin of the ferromagnetic instability. In the case of

Figure 2

q-dependence of the unenhanced magnetic susceptibility

of a-Fe (lattice parameter a ¼5.27 atomic units) and Cr

(a ¼5.45 atomic units); q is given in units of 2p/a. The

susceptibilities are scaled to assume a unity value at the

point of maximum. Calculation was carried out with the

scheme of Sandratskii and Ku

¨

bler (1992).

107

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism

chromium, the behavior is the opposite: the suscep-

tibility for q ¼ 1ðin units of

1

2

4KÞ is more than three

times that for q ¼0. The difference between these two

cases reflects the tendency for systems with half-filled

d-bands to be antiferromagnetic, in contrast to the

systems at the end of the 3d series, which order

ferromagnetically (Heine and Samson 1983).

From Eqn. (13), it is seen that the largest contri-

bution to the susceptibility is given by the pairs of

states which are separated in reciprocal space by the

vector q and are close in energy. Since the energy

difference contains one occupied and one unoccupied

state, these states lie close to the Fermi level. Indeed,

the Fermi surface of chromium possesses two similar

sheets shifted in the reciprocal space by the vector q,

which is close to

1

2

K (see Fawcett (1988) for details).

This nesting of the sheets of the Fermi surface is im-

portant for the formation of the antiferromagnetic

instability.

2.3 Spiral Magnetic Structure

The spatial variation of the directions of the atomic

magnetic moments in the simplest magnetic struc-

tures—ferromagnetic and two-sublattice antiferro-

magnetic—can be described by the wave vectors

equal, respectively, to 0 or

1

2

K. Also, the magnetic

structures described by an intermediate value of vec-

tor q were found experimentally.

The spiral magnetic structure can be defined by the

formula:

m

n

¼ mðcosðq R

n

Þsiny; sinðq R

n

Þsiny; cosyÞð14Þ

where m

n

is the magnetic moment of the nth atom

and (q R

n

), y are polar coordinates. For vector q

incommensurate with the vectors of the reciprocal

lattice, the magnetic unit cell representing a transla-

tionally invariant part of the magnetic crystal is in-

finite. The spiral structure possesses, however, a

special symmetry which, for an arbitrary q, allows

reduction of the consideration to the unit cell of the

chemical lattice.

The spiral structure, Eqn. (14), is invariant with

respect to the translation of the crystal by an arbi-

trary lattice vector R

n

, accompanied by the rotation

of all atomic moments by an angle qR

n

about the z

axis. Such operations, {(qR

n

)7R

n

}, are called gener-

alized translations. The Kohn–Sham Hamiltonian

of the magnetic moments of the spiral structure

(Sandratskii 1998) commutes with the generalized

translations {(qR

n

)7R

n

}. As a consequence of the

generalized translational symmetry, a generalized

Bloch theorem can be formulated:

fðqR

n

Þ7R

n

gc

k

ðrÞ¼expðikR

n

Þc

k

ðrÞð15Þ

where the vectors k lie in the first Brillouin zone

of the chemical lattice. The theorem, Eqn. (15), is

sufficient for the reduction of the problem, for an

arbitrary value of q, to the consideration of the

chemical unit cell of the crystal.

The formation of spiral structure leads to the hy-

bridization of the states of the nonmagnetic crystal

which are separated in the reciprocal space by vector

q. The importance of this hybridization is reflected in

the formula for the susceptibility, Eqn. (13), and is

closely related to the phenomenon of the Fermi sur-

face nesting discussed in the case of chromium.

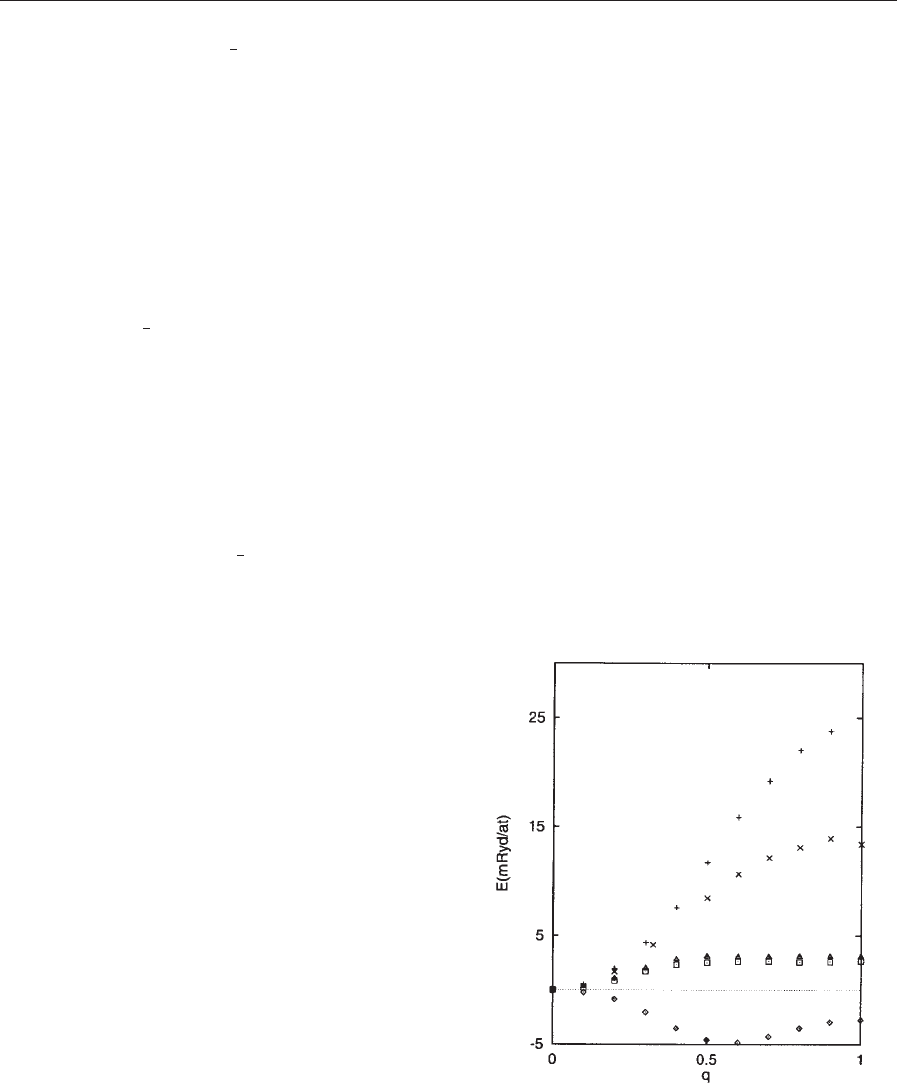

Figure 3 shows the calculated q-dependence of

the total energy for a number of transition metals

(Sandratskii and Ku

¨

bler (1992); see also the paper by

Mryasov et al. (1991) for the first, first-principles

calculation of g-iron). In agreement with experiment,

the ground state was found to be ferromagnetic for

all metals, except for the case of g-iron. In g-iron, the

minimum of the total energy occurs at a finite value

of q, i.e., the ground state is spiral.

Another example of the spiral structure is that in

the heavy rare-earth metals (REM) (see Localized 4f

and 5f Moments: Magnetism; Magnetism in Solids:

General Introduction). The intra-atomic exchange

interaction between the 4f states and the valence 5d

and 6s states leads to the spin polarization of the

valence states. In the crystal, the valence states of

different atoms hybridize and form energy bands.

The energy of the hybridized valence states depends

on the directions of the 4f moments of different

atoms.

Figure 3

The total energy as a function of q for the (001)

direction. B ¼g-Fe; þ¼a-Fe; & ¼fcc-Co; ¼hcp-

Co; ¼Ni. In all calculations y ¼901. (Sandratskii and

Ku

¨

bler (1992)).

108

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism

Early calculations of the q-dependence of the un-

enhanced susceptibilities (Jensen and Mackintosh

1991) gave the maximum at the q values close to

the experimentally determined wave vectors of the

spiral structures. In Fig. 4, a first-principles calcula-

tion by Nordstro

¨

m and Mavromaras (1999) of the

total energy of thulium as a function of q is shown.

2.4 Role of the Spin–Orbit Coupling

In the calculations of the magnetic structure dis-

cussed up to now, the SOC (see Sect. 1.3) was not

taken into account. With the SOC being neglected, an

arbitrary rotation of all atomic magnetic moments by

the same angle does not change the energy. However,

the dependence of the energy of the system on the

direction of the magnetic moments with respect to the

lattice, that is, the magnetic crystalline anisotropy, is

a property of primary importance in numerous tech-

nical applications (see also Sect. 3).

In bcc iron, the energy of magnetic anisotropy is of

the order of 10

4

mRy per atom, and is five orders of

magnitude smaller than the interatomic exchange in-

teraction. In the case when the SOC energy becomes

comparable with the interatomic exchange interac-

tion, it influences substantially not only the direction

of the atomic moments with respect to the lattice, but

also the relative directions of the moments. Indeed,

experimental determination of the magnetic structure

in heavy REM revealed a distortion of the spiral

structure due to the influence of the magnetic anisot-

ropy (Jensen and Mackintosh 1991).

The influence of the SOC on the formation of the

magnetic structure increases further when one moves

from the 4f systems (see Localized 4f and 5f Moments:

Magnetism) to the 5f systems (see 5f Electron Sys-

tems: Magnetic Properties). The most effort has been

devoted to the magnetic structure of uranium com-

pounds. The hybridization of the 5f states with the

states of other atoms is essential for the physics of the

uranium compounds. On the other hand, the 5f states

experience strong spin–orbit coupling.

The importance of the SOC can be illustrated by

the phenomenon of the symmetry-predetermined

noncollinearity of the magnetic structure. To intro-

duce this effect, let us consider a collinear magnetic

structure, and let y be a parameter which describes

the noncollinear magnetic structures obtained with

the deviation of the magnetic moments from the col-

linear directions. y

0

¼0 corresponds to the collinear

structure. The following criterion of the instability of

the magnetic structure can be formulated: the struc-

ture corresponding to y ¼y

0

can be stable only in the

case that this state is distinguished by symmetry,

compared to the states obtained with infinitesimal

variation of parameter y (Sandratskii (1998) and ref-

erences therein). Indeed, only in this case can the

minimum of the total energy be at y ¼0.

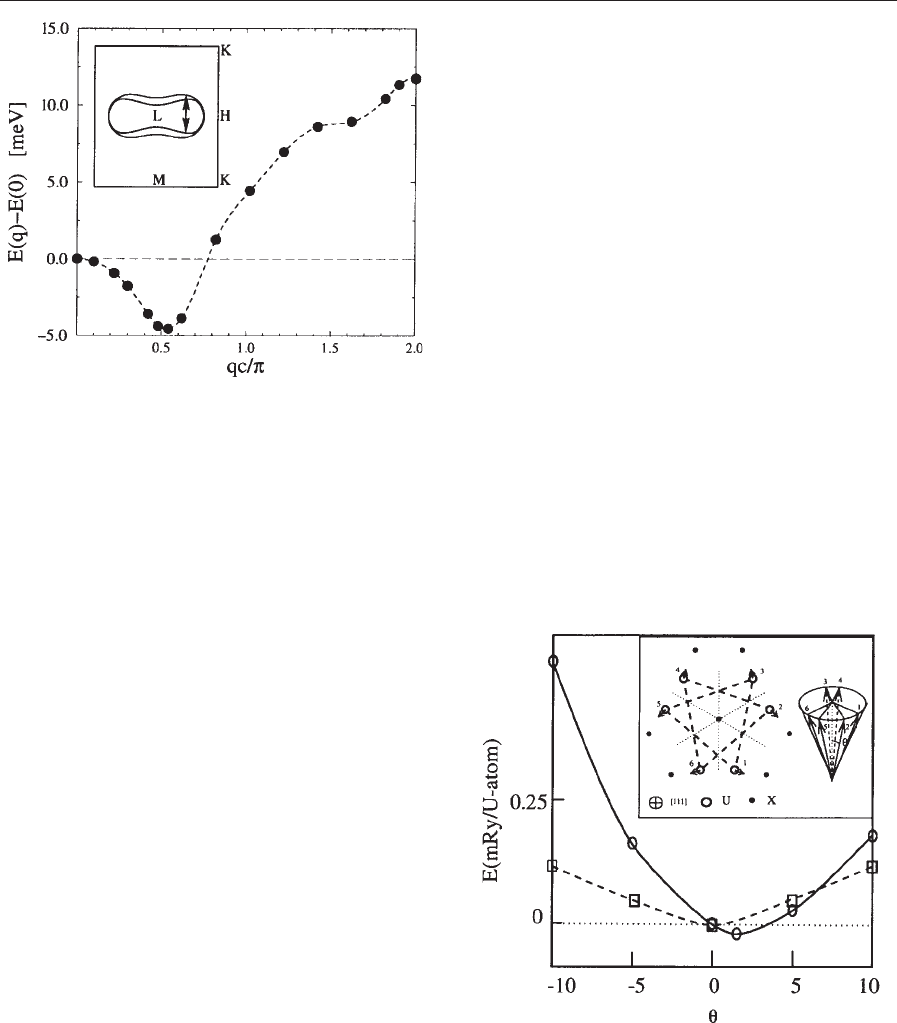

The effect of the symmetry-predetermined noncol-

linearity is illustrated in Fig. 5 by the example of

U

3

P

4

. The inset shows the experimentally deter-

mined magnetic structure of U

3

P

4

. An SDFT calcu-

lation starting with the collinear ferromagnetic

Figure 5

The total energy of U

3

P

4

as a function of the deviation

of the magnetic moments from the (111) axis. Solid/

dashed line shows the result of the calculation with/

without the spin–orbit coupling, respectively. The inset

shows the projection of the crystal and magnetic

structure to the (111) plane. The magnetic moments

form a cone structure.

Figure 4

The q-dependence of the total energy of T

m

. The inset

shows the nesting property of the Fermi surface.

(Nordstro

¨

m and Mavromaras (1999))

109

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism