Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Anisotropy), such as SmCo

5

,Sm

2

Co

17

, and Nd

2

Fe

14

B

are the basis for high-performance rare earth mag-

nets. Samarium–cobalt magnets exhibit the highest

coercive fields

J

H

c

and (Nd,Dy)–(Fe,Co)–B:(Al,Cu,

Ga) magnets show the highest value of remanence B

r

and energy density product (BH)

max

obtained so far.

Rare earth magnets are divided into the group of the

so-called single phase, nucleation-controlled magnets,

based on the SmCo

5

or Nd

2

Fe

14

B hard magnetic

phases, and the group of domain wall pinning con-

trolled, multiphase magnets (see Coercivity Mecha-

nisms). Two-phase magnets, which are nowadays also

used in high-temperature advanced power applica-

tions consist of a continuous Sm(Co,Cu)

5–7

cellular

precipitation structure within a Sm

2

(Co,Fe)

17

matrix

phase. Nanocrystalline rare earth magnets exhibit

microstructures of single phase, two phase and mul-

tiphase character, in which the inhomogeneous mag-

netization behavior near the intergranular regions

can create remanence enhancement (see Magnets:

Remanence-enhanced).

High-performance rare earth permanent magnets

are produced with different composition and by var-

ious processing techniques (Strnat 1988, Herbst

1991), which influence the complex, multiphase

microstructure of the magnets, such as size and

shape of grains, the orientation of the easy axes of the

grains and the distribution of phases. The formation

and distribution of the phases is determined by the

composition of the magnets and the annealing treat-

ment. The grain size of the magnets and the align-

ment of the grains especially strongly depend on the

processing parameters:

*

grain sizes in the range between 10 nm and

500 nm are obtained by melt-spinning, mechanical

alloying (see Magnets: Mechanically Alloyed) and the

HDDR (hydrogenation-disproportionation-desorp-

tion-recombination) process (see Magnets: HDDR

Processed),

*

sintered (see Magnets: Sintered) and hot worked

magnets (see Textured Magnets: Deformation-in-

duced) exhibit grain sizes above 1 mm.

The hysteresis properties of the magnets are gov-

erned by a combination of the intrinsic properties of

the material, such as saturation polarization J

s

, mag-

netic exchange and magnetocrystalline anisotropy of

various phases, and the influence of the microstruc-

ture on the magnetization reversal process (see Mag-

netic Hysteresis). The intergranular structure between

the grains plays a significant role in determining the

magnetic properties, thus a detailed understanding of

the microstructure and of the grain boundaries is

necessary. Magnetic domain structures (see Magnets,

Soft and Hard: Domains), which are a result of the

occurrence of magnetic stray fields, are directly in-

fluenced by the microstructural features.

The direct observation of microstructure and mag-

netic domain structure leads to a deeper insight into

the origin of the coercivity of rare earth magnets.

Advanced analytical methods, such as high-resolu-

tion electron microscopy (see Magnetic Materials:

Transmission Electron Microscopy), magnetic force

microscopy (see Magnetic Force Microscopy), posi-

tion sensitive 3D atom probe, and other techniques

have been used to study rare earth magnets. Mode-

ling of magnetic materials is performed at various

levels and becomes more important as computer

power is improved. Numerical 3D micromagnetic

simulations of the magnetization reversal process in-

corporate realistic microstructures. Advanced analyt-

ical investigations and future simulations should be

able to predict optimal microstructures and proper-

ties for given hard and soft magnetic materials (Fidler

and Schrefl 2000).

1. Nucleation-controlled Magnets

The basic microstuctural feature of polycrystalline

SmCo

5

-orNd

2

Fe

14

B-based magnets is the individual

hard magnetic grain with its size, shape, and orien-

tation parameters. The ideal microstructure of the

so-called single phase magnets consists of aligned

single-domain hard magnetic particles. Strictly speak-

ing, these magnets show a complex, multiphase

microstructure with various types of intergranular

phases according to their phase diagram and phase

relations. The amount of each phase and their dis-

tribution within polyphase materials are perhaps the

most complex of the microstuctural parameters. The

occurrence of the multiphase microstructure is one of

the reasons why the coercive field of the magnets

according to the magnetocrystalline anisotropy field

of the hard phase, such as 30700 kAm

1

for SmCo

5

and 6050 kAm

1

for Nd

2

Fe

14

B, is never reached in

practice.

The microstructure of single phase, anisotropic

SmCo

5

-type magnets consists of grains oriented par-

allel to the alignment direction. Most of the SmCo

5

grain interiors show a low defect density. The grain

diameter exceeds the theoretical single domain size

and is in the order of 5–10 mm. Besides SmCo

5

grains,

grains with densely packed, parallel stacking faults

perpendicular to the hexagonal c-axis are observed.

Such basal stacking faults correspond to a transfor-

mation of the SmCo

5

crystal structure into the sa-

marium-rich Sm

2

Co

7

and Sm

5

Co

19

structure types.

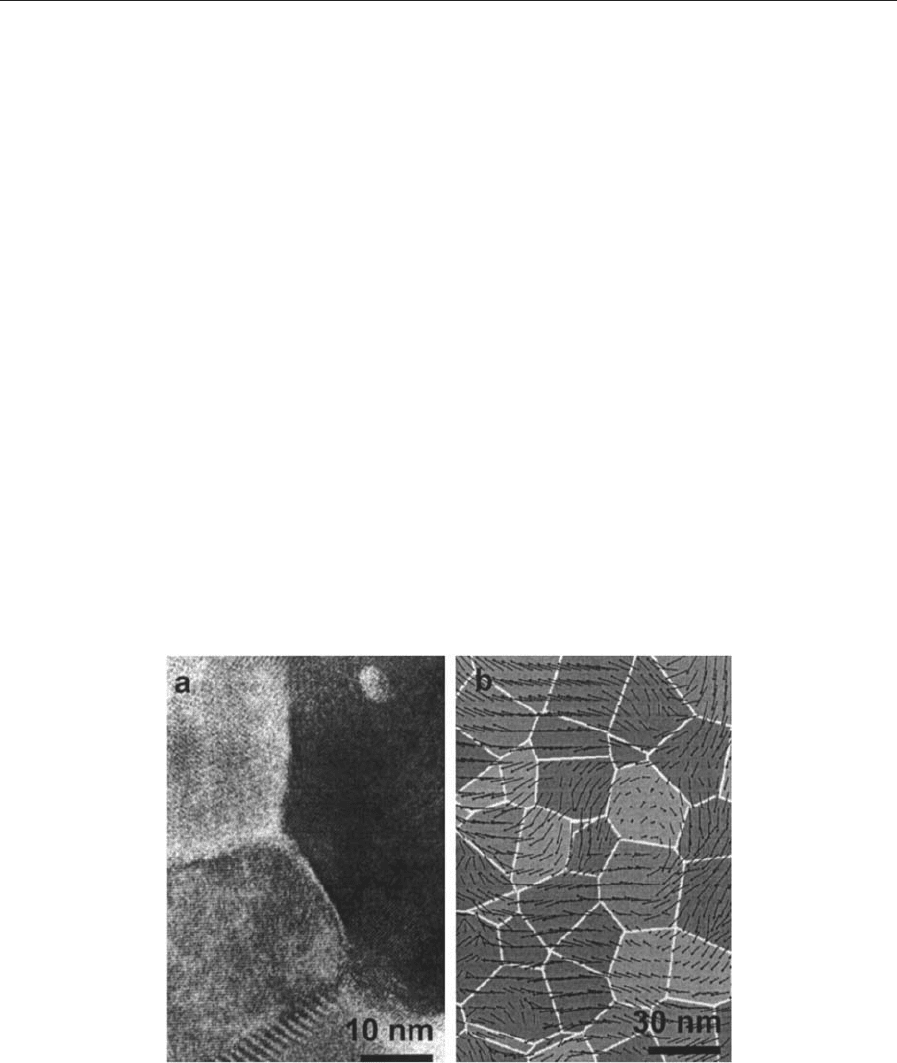

Using high-resolution electron microscopy together

with x-ray microanalysis, the different polytypes and

structural modifications of these samarium-rich phas-

es are characterized. Incoherent precipitates with di-

ameters up to 0.5 mm were identified as Sm

2

O

3

or

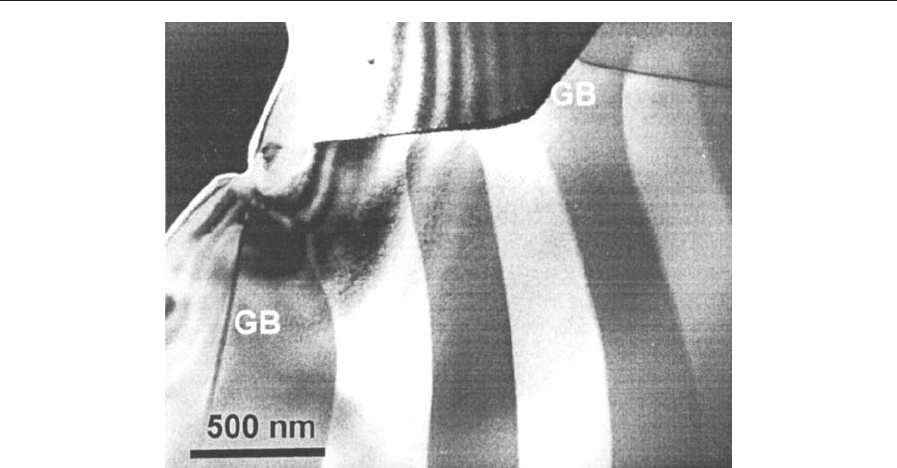

CaO inclusions. The electron micrograph of Fig. 1

shows a defect-free SmCo

5

grain separated into mag-

netic domains in the demagnetized state.

In SmCo

5

-type sintered magnets, the coercivity

is determined by the nucleation field of reversed

domains which is lower than the coercivity of a

1030

Permanent Magnets: Microstructure

magnetically saturated particle with a single domain

structure and nucleation by the expansion field of the

reversed domains. The nucleation of reversed do-

mains takes place in regions with low magnetocrys-

talline anisotropy. Rare earth-rich precipitates

mainly deteriorate the

J

H

c

of the final magnet. The

formation of these phases is due to the addition of a

rare earth-rich sintering aid phase before the sintering

process. The coercivity can be improved by adding

small amounts of transition metal powders or tran-

sition metal oxides. TEM studies show that the

chemical composition, the size distribution, and the

impurity content (oxygen content) of the starting

powder material are important factors for the mag-

netic properties of SmCo

5

-type sintered magnets. For

lower-cost magnets, samarium is partly substituted

by a mixture of cerium–mischmetal elements or, for

improved magnetic properties, by praseodymium,

thus three groups of SmCo

5

-type sintered magnets

are distinguished:

*

(CeMM,Sm)Co

5

low J

s

, low (BH)

max

,

*

SmCo

5

high

J

H

c

,

*

(Pr,Sm)Co

5

high (BH)

max

.

Microstructural investigations on sintered magnets

of the type (CeMM,Sm)Co

5

and (Pr,Sm)Co

5

showed

similar results as in the case of SmCo

5

sintered mag-

nets. The corresponding x-ray spectra of the diffe-

rent phases showed a mixture of rare earth elements

due to their ratio of the nominal composition of the

magnet.

2. Doped and Substituted Nd

2

Fe

14

B Magnets

The coercive field of high-performance Nd

2

Fe

14

B-

based magnets is determined by the uniaxial magneto-

crystalline anisotropy as well as by the magnetostatic

and exchange interactions between neighboring hard

magnetic grains. The long-range dipolar interactions

between misaligned grains are more pronounced in

large-grained magnets, whereas short-range exchange

coupling reduces the coercive field in small-grained

magnets. Different substituent (S1, S2) and dopant

(M1, M2) elements influence the microstructure,

coercivity, and corrosion resistance of advanced

(Nd,S1)–(Fe,S2)–B:(M1,M2) magnets. The multi-

component composition of the magnets leads to the

formation of nonmagnetic and soft magnetic phases.

Generally, two types of substituent elements, which

replace the rare earth element or the transition ele-

ment sites in the hard magnetic phase, and two types

of dopant elements were found. Selected substituent

elements replace the neodymium atoms (S1 ¼Dy,Tb)

and the iron atoms (S2 ¼Co,Ni,Cr), respectively, in

the hard magnetic phase and considerably change

intrinsic properties, such as the spontaneous polari-

zation, the Curie temperature, and the magnetocrys-

talline anisotropy. The main difference between

substituent and dopant elements is the solubility

range within the Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase. Investigations

performed on sintered, melt-spun, mechanically al-

loyed, and hot-worked magnets have shown that two

Figure 1

Lorentz electron micrograph showing the magnetic domain configuration in the demagnetized state of a sintered

SmCo

5

magnet. The coercivity mechanism is controlled by nucleation and expansion of reversed domains.

1031

Permanent Magnets: Micro structure

different types of dopants can be distinguished inde-

pendently of the processing route. Depending on the

type, the dopant elements form additional intergran-

ular rare earth-containing or boride phases (Fidler

and Schrefl 1996):

*

Type 1 dopants (M1 ¼aluminum, copper, gal-

lium, germanium) form binary or ternary neodym-

ium-containing phases.

*

Type 2 dopants (M2 ¼titanium, zirconium; va-

nadium, molybdenum; niobium, tungsten) form bi-

nary or ternary boride phases.

In summary, the following phases were identified

by TEM investigations:

*

Primary hard magnetic phase: Nd

2

Fe

14

B.

*

Secondary phases:

neodymium-rich liquid sintering phase, stabi-

lized by some amount of oxygen and iron

Nd

1þe

Fe

4

B

4

M1-Nd ðCuNd; GaNd

3

; Ga

3

Nd

5

Þ

M1-Fe-Nd ðM1

1þx

Fe

13x

Nd

6

Þ

M2-B ðTiB

2

; ZrB

2

Þ

M2-Fe-B ðV

2x

Fe

1þx

B

2

; Mo

2x

Fe

1þx

B

2

;

NbFeB; WFeBÞ

a-Fe

Oxide-phases ðNd

2

O

3

; yÞ:

*

Additional phases in Dy- and Co-substituted

and M1- and M2-doped magnets:

Nd(Co,Fe)

4

B

Nd(Co,Fe)

2

Nd

3

Co

dysprosium-containing phases.

Intergranular phases change the coupling behavior

between the hard magnetic grains. Nonmagnetic

phases eliminate the direct exchange interaction and

also reduce the long-range magnetostatic coupling

between the hard magnetic grains; both effects lead to

an increase of coercivity. The formation of interme-

tallic, soft magnetic Nd(Fe,S2) phases, such as the

Laves type Nd(Fe,S2)

2

-phase, deteriorate the co-

ercivity of the magnets. If dopant elements M1 or M2

are added to NdFeB, the coercivity is generally in-

creased and the corrosion resistance (see Permanent

Magnets: Corrosion Properties) is improved. This is

the case if the neodymium-rich intergranular phase is

replaced by other phases, such as AlFe

13

Nd

6

and

Nd

3

Co, especially in large-grained sintered magnets.

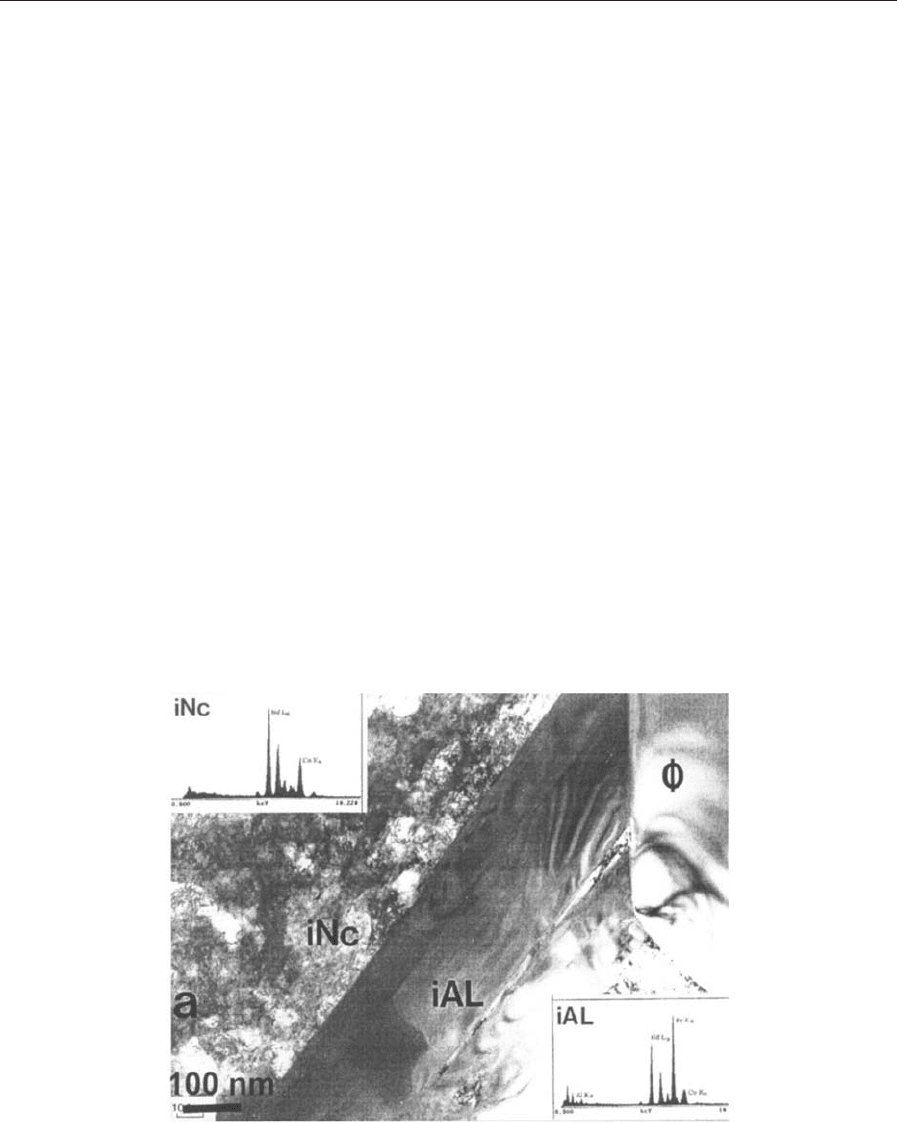

The TEM micrograph of Fig. 2 shows the additional

intergranular Al

1

Fe

13

Nd

6

and Nd

3

Co phases in a

Nd(Fe,Co)B:(Al,Mo) magnet. On the other hand, the

decrease of the volume fraction of the hard magnetic

phase within the magnet decreases the remanence.

The processing route of the magnet strongly influ-

ences the grain size and grain size distribution. The

coercive field in sintered magnets strongly depends on

the sintering parameters, such as temperature and

time. Nanocrystalline and submicron magnets are

obtained by the melt-spinning route, by mechanical

alloying, or by the HDDR process. Hot pressing and

die upsetting of NdFeB ribbon materials reveals a

densely packed, anisotropic magnetic material. Plate-

let-shaped grains with diameters less than 1 mm are

Figure 2

TEM micrograph showing intergranular phases, Al

1

Fe

13

Nd

6

(iAL) and Nd

3

Co (iNc), besides the Nd

2

(Fe,Co)

14

B(F)

phase in a Nd-(Fe,Co)-B:(Al,Mo) magnet.

1032

Permanent Magnets: Microstructure

observed by TEM investigations. The degree of ori-

entation of the platelets, which are stacked transverse

to the press direction with the easy c-axes perpendic-

ular to the face of each grain, determines the reman-

ence and coercive field of the magnet.

The degree of alignment, size and shape of the

grains, and the intergranular regions within the rib-

bons control the macroscopic magnetic properties.

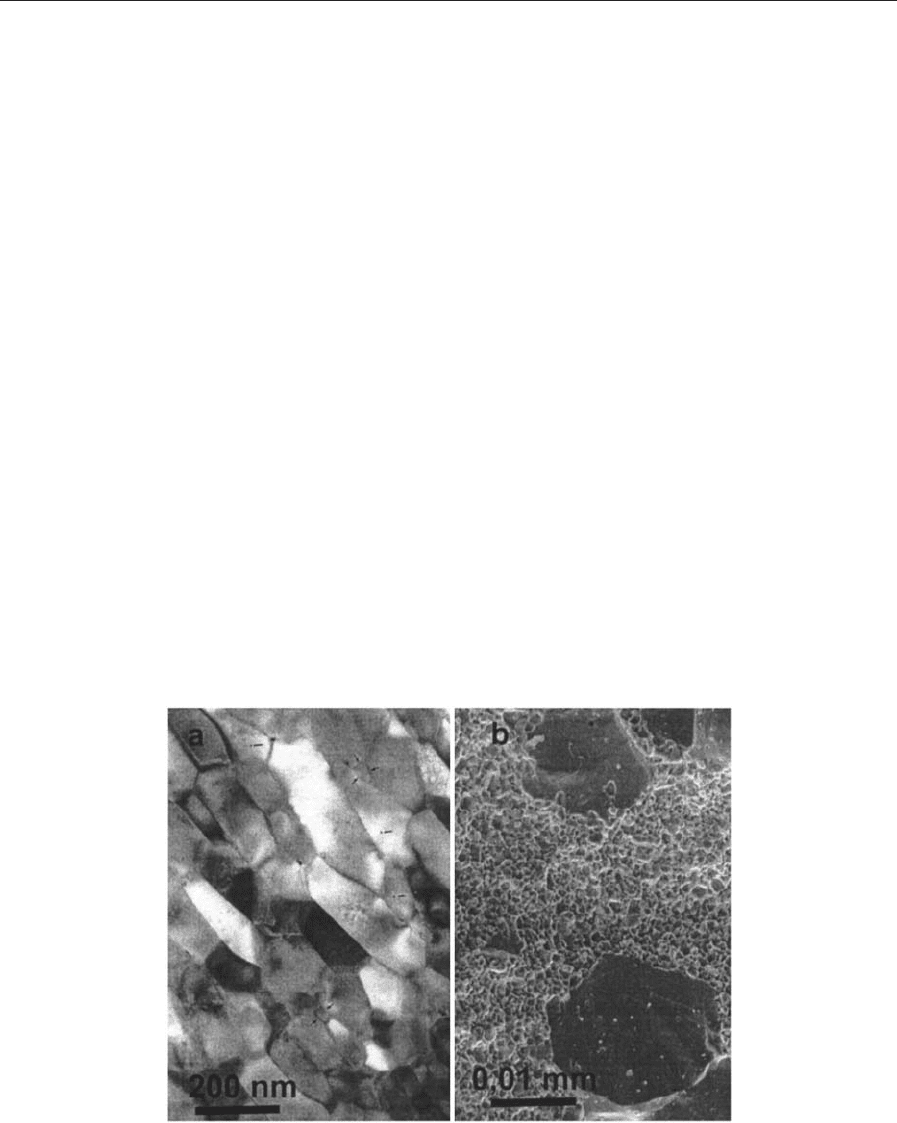

Die-upsetting modifies the spheroidal grains (Mishra

1987) after hot pressing to platelets as shown in the

TEM micrographs of Fig. 3(a). Misaligned grains,

which are clearly visible, deteriorate the remanence.

The c-axis for each grain runs perpendicular to the

straight elongated edge. A neodymium-rich phase is

found among the platelet-shaped grains as a fine layer

between the straight edges or as pockets at the end of

the platelets or between the misaligned and aligned

grains. On the other hand, the magnets with a lower

remanence show a microstructure with more equi-

axed grains. In most of the melt-spun magnets, re-

gions with abnormally grown, large grains are found.

Some of these grains are fully developed, platelet-

shaped grains (see Textured Magnets: Deformation-

induced).

NdFeB sintered magnets possessing outstanding

magnetic properties have succeeded in becoming a

major permanent magnet material since their inven-

tion in 1983 (see Magnets: Sintered). The drastic

increase of the energy density product of newly

developed Nd

2

Fe

14

B-based magnets enabled the

invention of many new applications of permanent

magnets. Applications of highest energy density mag-

nets (4400 kJm

3

) are expanding (see Magnetic Ma-

terials: Domestic Applications; Permanent Magnets:

Sensor Applications). These magnets are produced by

a conventional powder metallurgical process which is

essentially based on alloy melting, coarse milling,

pulverizing, pressing in a magnetic field, sintering,

heat treating and surface coating. The theoretical

value of the maximum energy product of Nd

2

Fe

14

B-

based magnets is calculated to be 512 kJm

3

assum-

ing 100% perfect alignment and 100% volume

fraction of the hard phase. In order to densify the

magnets up to the theoretical density, it is very im-

portant to control the composition of magnets thus

generating a sufficient amount of liquid phase at sin-

tering. Several authors (Kaneko 1999), have report-

edly obtained NdFeB-based magnets with 400 kJm

3

energy density product by:

*

keeping the oxygen content low,

*

using the powder mixing technique,

*

increasing the magnetizing field and reducing

the pressure during compaction,

*

using the rubber isostatic pressing (RIP) tech-

nique to improve the orientation of the particles in

the green compact to obtain sintered magnets with

perfect orientation.

In RIP, magnet powder is subjected to such a

strong pulsed field just before the compaction that

the powder in the rubber mold is thoroughly oriented

(Sagawa and Nagata 1993). Then the powder is

compacted isostatically, while the orientation is

Figure 3

(a) TEM micrograph of a hot-pressed and die-upset Nd

14

Fe

72

Co

7

B

6

Ga

1

magnet. (b) SEM micrograph of a fractured

surface showing the abnormally grown grains in a sintered Nd

13.7

Fe

bal

B

5.95

Cu

0.03

Al

0.7

magnet.

1033

Permanent Magnets: Micro structure

completely kept. The misalignment of the hard mag-

netic grains with a diameter of 2–5 mm is in the best

case of the order of less than 141. The oxygen content

of the magnets has to be reduced from values of 4000–

6000 ppm to a value o1000 ppm. A high oxygen

content is one limiting factor to decreasing the neo-

dymium content in order to improve the volume frac-

tion of the hard magnetic phase. The squareness of

the demagnetization curve and the coercive field dras-

tically decrease as abnormal grain growth (AGG) of

the Nd

2

Fe

14

B grains occurs (Rodewald et al. 1997).

The influence of oxygen on the hard magnetic prop-

erties is more complex. The oxygen content strongly

affects the AGG, and the magnets with higher oxygen

content have the higher critical temperature at which

the AGG occurs. The SEM micrograph of Fig. 3(b)

shows abnormally grown hard magnetic grains

embedded within a matrix of grains with a diameter

of 3–5 mm. Even the sintering process influences the

degree of misalignment of the grains. Lowest mis-

alignment is obtained by isostatic die pressing

(11–141), followed by transverse field die pressing

(18–201), and axial field die pressing (25–271).

3. Pinning Controlled Sm(Co,Cu,Fe,Zr)

7.5–8

Magnets

Copper-containing cobalt-rare earth magnets with a

composition of Sm(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)

6–8

exhibit domain

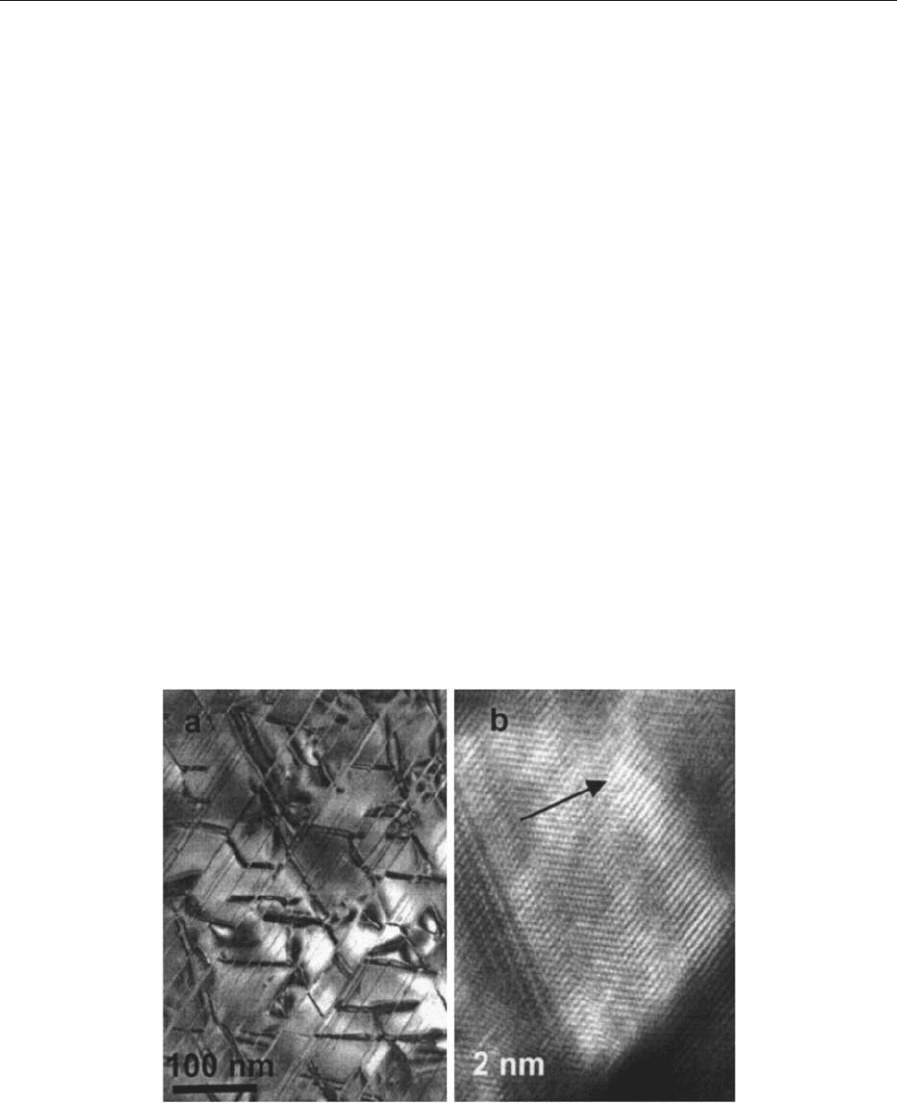

wall pinning controlled magnetization curves. TEM

investigations show a fine cell morphology with

about 50 nm 200 nm in size. The rhombic cells of

the type Sm

2

(Co,Fe)

17

are separated by a Sm(Co,

Cu)

5–7

-cell boundary phase (Fig. 4(a)). The develop-

ment of the continuous, cellular precipitation struc-

ture is controlled by the growth process and the

chemical redistribution process and is determined by

the direction of zero deformation strains due to the

lattice misfit between the different phases. The cellu-

lar precipitation structure is formed during the iso-

thermal aging procedure, whereas the chemical

redistribution of the transition metals during the step

aging procedure increases the coercivity of the final

magnet. Growth of the cell structure occurs primarily

during the isothermal aging procedure and involves

the diffusion of samarium. In magnets with high co-

ercivities (41000 kAm

1

), thin platelets are found

perpendicular to the hexagonal c-axis.

Contrary to high-coercivity magnets which contain

large crystallographic twins, a microtwinning within

the cell interior phase is observed by high-resolution

electron microscopy in low-coercivity magnets

(o500 kAm

1

) (Fig. 4(b)). The compositional differ-

ence between the cell boundary phase and the cell

interior phase and therefore the difference in magne-

tocrystalline anisotropy energy of the two phases

determines the coercive field. The platelet phase pre-

dominately acts as a diffusion path for the transition

metals and leads to a better chemical redistribu-

tion after the isothermal aging treatment and, there-

fore, to a higher coercivity of the magnet. Impurities,

Figure 4

(a) TEM micrograph showing the multiphase cellular microstructure of a precipitation-hardened Sm(Co,Cu,Fe,Zr)

7–8

magnet. (b) High-resolution image showing microtwinning behavior of the cell matrix phase of a low coercivity

magnet.

1034

Permanent Magnets: Microstructure

primarily oxygen or carbon, lead to the formation of

macroscopic precipitates of the Sm

2

O

3

, ZrC, TiC,

etc., and therefore impede the formation of the plate-

let phase and finally impede the chemical redistribu-

tion process.

A new series of magnets with H

c

up to 1050 kAm

1

at 400 1C has been developed by Chen et al. (1998).

These magnets have low temperature coefficients of

H

c

and a straight line B vs. H (extrinsic) demagnet-

ization curve up to 550 1C. High copper-, low iron-

and a higher samarium-concentration were found to

contribute to high coercivity at high temperatures

(see Magnets: High-temperature).

4. Nanocrystalline, Composite Nd

2

Fe

14

B/

(a-Fe,Fe

3

B) Magnets

Exchange interactions between neighboring soft and

hard grains lead to remanence enhancement of iso-

tropically oriented grains in nanocrystalline compos-

ite magnets (Kneller and Hawig 1991, Coehoorn

et al. 1989). Nanocrystalline, single-phase NdFeB

magnets with isotropic alignment show an enhance-

ment of remanence by more than 40% as compared

to the remanence of noninteracting particles, if the

grain size is of the order of 10–30 nm (Fig. 5(a)).

Numerical micromagnetic calculations have revealed

that the interplay of magnetostatic and exchange in-

teractions between neighboring grains influence the

coercive field and remanence considerably (Fidler

and Schrefl 2000). Soft magnetic grains in two- or

multi-phase composite permanent magnets cause a

high polarization. Hard magnetic grains induce a

large coercivity provided that the particles are

small and strongly exchange-coupled. The coercive

field shows a maximum at an average grain size of

15–20 nm. Intergrain exchange interactions override

the magnetocrystalline anisotropy of the Nd

2

Fe

14

B

grains for smaller grains, whereas exchange harden-

ing of the soft phases becomes less effective for larger

grains.

The magnetization distribution at zero applied field

for different grain sizes clearly shows that remanence

enhancement increases with decreasing grain size.

Owing to the competitive effects of magnetocrystal-

line anisotropy and intergrain exchange interactions,

the magnetization of the hard magnetic grains sig-

nificantly deviates from the local easy axis for a grain

size Dp20 nm. As a consequence, coercivity drops,

since intergrain exchange interactions help to over-

come the energy barrier for magnetization reversal.

With increasing grain size the magnetization becomes

nonuniform, following either the magnetocrystalline

anisotropy direction within the hard magnetic grains

or forming a flux closure structure in soft magnetic

regions. Neighboring a-Fe and Fe

3

B grains may form

large continuous areas of soft magnetic phase, where

magnetostatic effects will determine the preferred di-

rection of the magnetization. The large soft magnetic

Figure 5

(a) High-resolution electron micrograph of a nanocrystalline, single-phase Nd-Fe-B magnet with isotropic alignment.

(b) Calculated magnetization distribution with a vortex-like structure in a slice plane of a 40 vol.% Nd

2

Fe

14

B,

30 vol.% a-Fe, and 30 vol.% Fe

3

B magnet with a mean grain size of 30 nm for zero applied field. The magnetic

polarization remains parallel to the saturation direction within the soft magnetic grains, whereas it rotates towards the

direction of the local anisotropy direction within the hard magnetic grains.

1035

Permanent Magnets: Micro structure

regions deteriorate the squareness of the demagneti-

zation curve and cause a decrease of the coercive field

for D420 nm. A vortex-like magnetic state with van-

ishing net magnetization will form within the soft

magnetic phase if the diameter of the soft magnetic

region exceeds 80 nm. Figure 5(b) presents the calcu-

lated magnetization distribution in a slice plane of a

40 vol.% Nd

2

Fe

14

B, 30 vol.% a-Fe, and 30 vol.%

Fe

3

B magnet with a mean grain size of 30 nm for zero

applied field. The magnetic polarization remains par-

allel to the saturation direction within the soft mag-

netic grains, whereas it rotates towards the direction

of the local anisotropy direction within the hard mag-

netic grains (see Magnets: Remanence-enhanced).

5. Summary

Microstructural parameters, such as grain size, shape

of grains, crystal structure, crystal defects, orientation,

and composition of various phases are different in

SmCo

5

-, Sm

2

Co

17

-, and Nd

2

Fe

14

B-based permanent

magnet materials. The complex microstructure con-

siderably influences the magnetic reversal process. De-

tailed TEM analysis revealed various additional

binary and ternary phases in the intergranular region

between hard magnetic grains in doped and substitut-

ed NdFeB magnets. Intergranular phases change the

coupling behavior between the hard magnetic grains.

Nonmagnetic phases eliminate the direct exchange in-

teraction and also reduce the long-range magnetostat-

ic coupling between the hard magnetic grains; both

effects lead to an increase of the coercive field. The

neodymium-rich intergranular phase is necessary for

the liquid phase sintering process, but deteriorates the

corrosion stability and reduces the remanence.

In order to improve coercivity, remanence, and

energy density, it is necessary to increase the volume

fraction of the hard magnetic phase by decreasing the

amount of oxygen, neodymium and pores, and to

improve the degree of alignment of the Nd

2

Fe

14

B

grains. Oxygen is partly dissolved in the neodymium-

rich intergranular phase. By reducing the amount of

oxygen (o1000 ppm), abnormal grain growth during

sintering becomes more severe. The difference in

magnetic domain wall energy in precipitation-hard-

ened Sm(Co,Cu)

5

/Sm

2

(Co,Fe)

17

multiphase magnets

is the main factor determining coercivity. The inho-

mogeneous magnetization behavior near the intergra-

nular regions of nanocrystalline rare earth magnets,

which is directly responsible for remanence and co-

ercivity, is strongly influenced by the microstructural

parameters.

Bibliography

Chen C H, Walmer M S, Walmer M H, Liu S 1998 Sm

2

(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)

17

magnets for use at temperature 4400 1C.

J. Appl. Phys. 83, 6706–8

Coehoorn R, Mooij D B, Waard C D E 1989 Melt-spun per-

manent magnet materials containing Fe

3

B as the main phase.

J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 80, 101–7

Fidler J, Schrefl T 1996 Overview of NdFeB magnets and co-

ercivity. J. Appl. Phys. 79, 5029–34

Fidler J, Schrefl T 2000 Micromagnetic modeling—the

current state of the art. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 33,

R135–R156

Herbst J F 1991 R

2

Fe

14

B materials: Intrinsic properties and

technological aspects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 63, 819–98

Kaneko Y 2000 Highest performance of NdFeB magnet over 55

MGOe. IEEE Magn. 36, 3275–8

Kneller E F, Hawig R 1991 The exchange-spring magnet: a new

material principle for permanent magnets. IEEE Trans.

Magn. 27, 3588–600

Mishra R K 1987 Microstructure of hot-pressed and die-upset

NdFeB magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 62, 967

Rodewald W, Wall B, Fernengel W 1997 Grain growth kine-

tics in sintered NdFeB magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 33,

3841–3

Sagawa M, Nagata H 1993 Novel processing technology for

permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 29, 2747–51

Strnat K J 1988 Rare Earth–Cobalt Permanent Magnets. Ferro-

magnetic Materials. Elsevier, Oxford, Vol. 4 pp. 131–209

J. Fidler

Vienna University of Technology, Wien, Austria

Permanent Magnets: Sensor Applications

Sensors for the detection of magnetic fields in

combination with a permanent magnet (actuator)

are used in a variety of applications to measure the

relative position/angle between mechanical parts

(Roters 1941, Akoun and Yonnet 1984). Generally

speaking these applications are divided into switches

(e.g., end control of a linear unit) and analog or

incremental continuous measurement. A common

example for the latter group is all kinds of speed or

position control in electrical machines (Adenot et al.

1996).

Magnetic switches as compared to mechanical

micro-switches have no moving parts (except reed

switches). Therefore, their main advantage is the

theoretically infinite lifetime. In the case of continu-

ous positioning or rotation measurement magnetic

sensors are in competition with optical methods.

While the latter allow a more accurate positioning

measurement, the magnetic systems are less sensitive

to dust and external influence. The advantages and

drawbacks of competing methods have to be evalu-

ated carefully.

This article describes the functionality of sensors,

the design methods for the layout and optimization

of actuating magnets in sensor applications, typical

applications, as well as magnet examples with field

specifications.

1036

Permanent Magnets: Sensor Applications

1. Magnetic Sensors

1.1 Reed Switches

The direct correspondents to mechanical micro-

switches are reed switches. In these devices two ferro-

magnetic contacts are sealed in a glass tube in an inert

atmosphere. An external field serves to magnetize the

contacts and they are attracted by their induced

magnetic poles. Thus the contact will be closed. The

external field to close the switch is commonly given in

ampere turns defining the number of turns of a long

solenoid per mm length multiplied by the required

electric current necessary to close the switch. Typical

values are 8–80 ampere-turns. The field threshold to

open the switch again when the field is reduced is

normally about 20–60% below the closing field.

The hysteresis between closing and opening is de-

termined by the magnetic hardness of the contact

material and by the geometry of the whole switch.

Thus to reduce the switching hysteresis a very low

coercive, magnetic material has to be used for the

contacts and the switching distance between the two

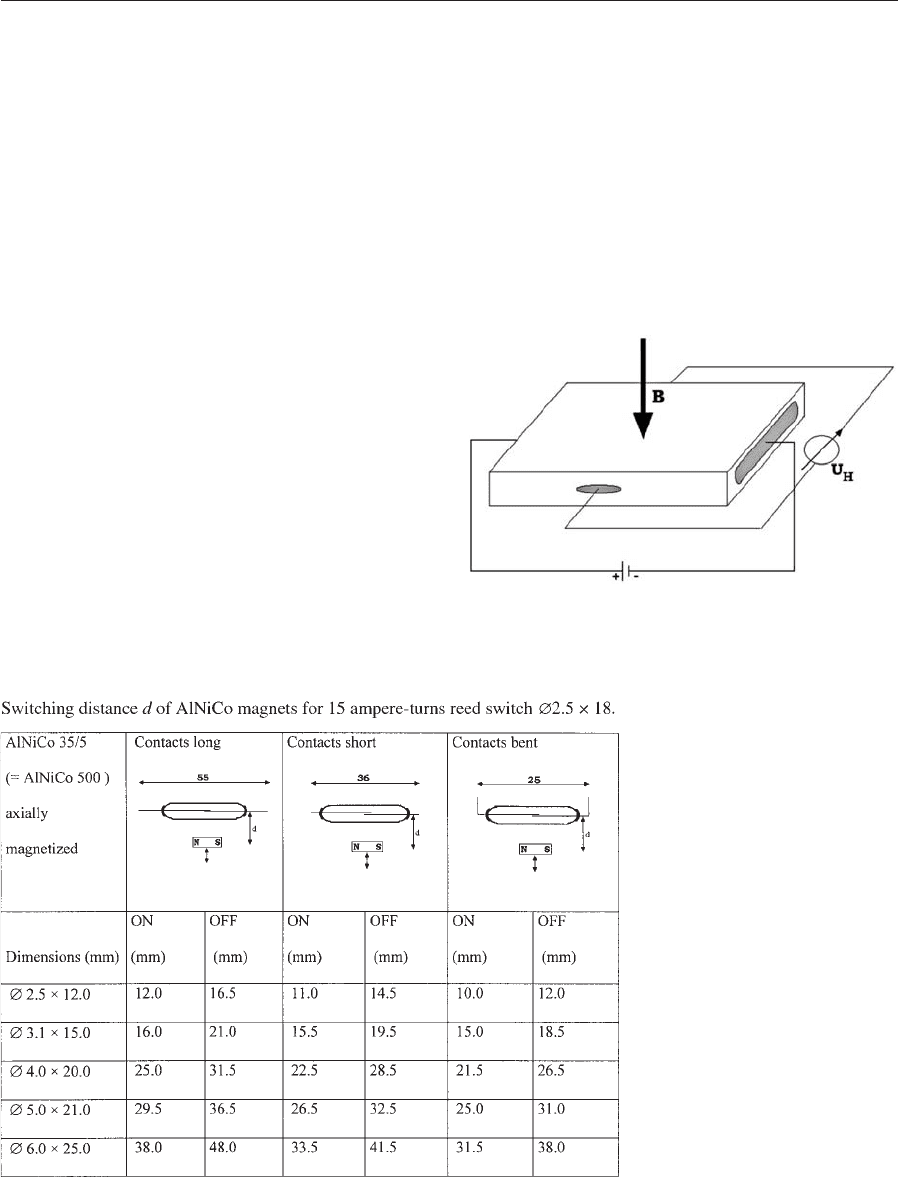

contacts has to be minimized. As an example Table 1

describes the switching behavior of a 15 ampere-turns

switch driven by different AlNiCo 35/5 rods.

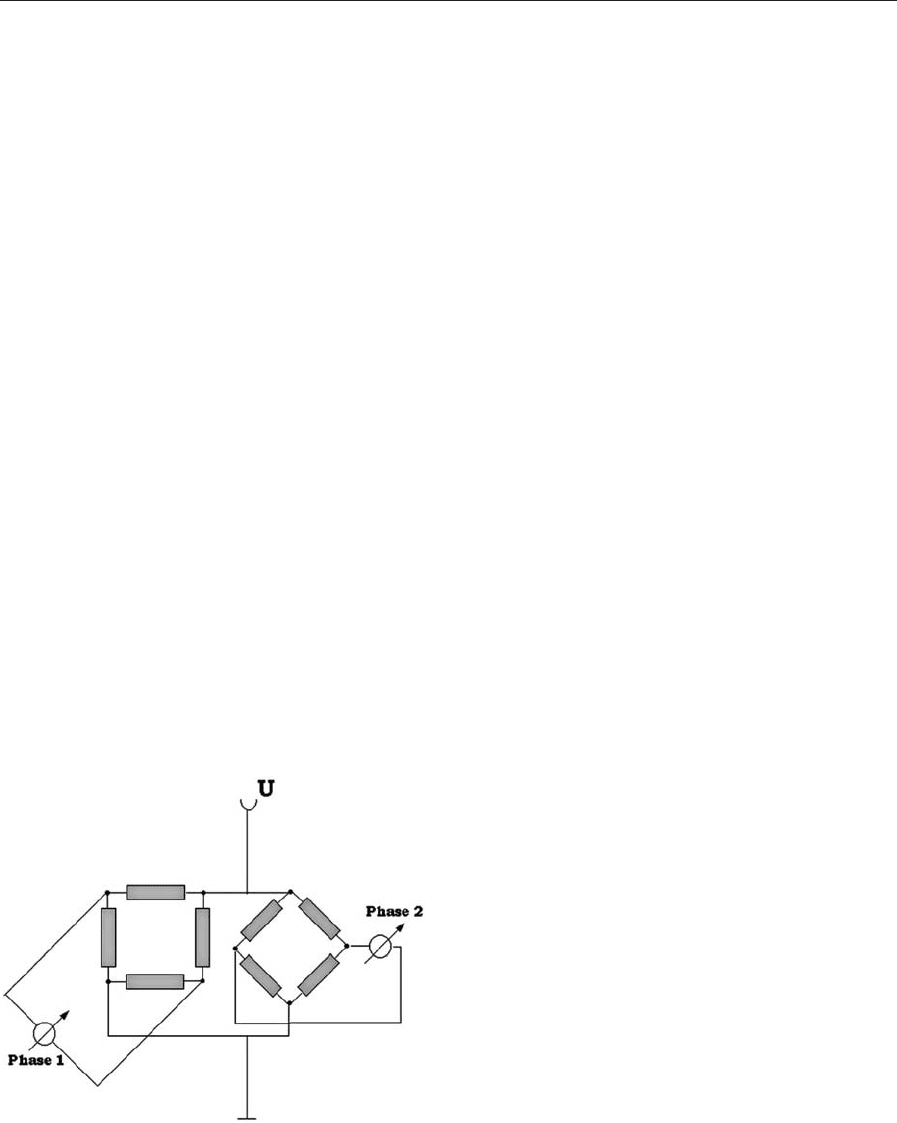

1.2 Hall Probes

Hall effect sensors are based on a thin film of semi-

conducting material (typically indium arsenide) in

which a voltage perpendicular to an applied current

and an applied magnetic field appears (Fig. 1). This

voltage is a direct measure of the magnetic field as

long as the current is constant. These kinds of sensors

with typical dimensions of the sensitive element of

0.6 mm 0.2 mm are often combined with an ampli-

fier. A following Schmitt trigger transforms the an-

alogue signal to a digital signal if required. The

switching hysteresis is normally smaller than for reed

switches. For analogue sensors compensation is nec-

essary for the temperature drift and for nonlinearity

effects.

If multipole fields with a small pole pitch are to be

detected by Hall probes it is necessary to keep in

Table 1

Figure 1

Schematic view of a Hall probe.

1037

Permanent Magnets: Sensor Applications

mind that the magnetic field is averaged over the size

of the sensitive area in the element and thus meas-

uring results are dependent on the sensor type. In a

chip housing the Hall probe is typically 0.3–0.8 mm

behind the surface of the housing.

1.3 XMR Sensors

Magnetoresistance (MR) sensors use the field de-

pendence of the electric resistance in a conducting or

a semiconducting probe. While conventional MR ef-

fects are rather small in most semiconductors (about

1–3%), there has been a renaissance of these kind of

sensors due to extremely large MR effects (XMR

sensors), called anisotropic MR (AMR) (see Magne-

toresistance, Anisotropic), giant MR (GMR) and,

colossal MR (CMR) (see Giant Magnetoresistance).

Even though the traditional MR effect has been used

to measure the field strength, MR and XMR sensors

are now, and in the near future will be more and more

used to measure field angles by evaluating the change

of resistivity in two directions. The principle of this

method is shown in Fig. 2.

The in-plane magnetic field is measured in two

Wheatstone bridges tilted at an angle of 45 1. The

measured voltages phase 1 and phase 2 correspond to

the magnetic field angle j by phase 1 ¼kcos(2j) and

phase 2 ¼ksin(2j).

The normal working range of sensors is about

10–100 kAm

1

. Smaller fields can lead to deviations

from the simple correlation between the field strength

and the measured voltage while higher fields can

irreversibly destroy some sensors.

1.4 Proximity Sensors

These kinds of sensors are used in many kinds of

automation. The approach of a ferromagnetic or

conducting part to a coil is detected by the changed

inductance of the coil. The coil forms a part of an LC

circuit of which the frequency is measured with a high

accuracy.

1.5 Induction Coils

In dynamical devices rotating with a constant speed

the induced voltage in a coil can be evaluated to de-

termine the angular position of a spindle. Typically

multipole magnets are fixed to a spindle and the ro-

tation speed can be detected by either the amplitude

of the induced a.c. voltage or by counting the periods

of this voltage. This method is used for speed control

in tool machines and in washing machines.

1.6 Impulse Wire Sensors

In these, also called Wiegand sensors, a wire with a

single magnetic domain is magnetically reversed and

one corresponding large Barkhausen jump is detected

by a coil (Rauscher and Radeloff 1991).

1.7 Permanent Magnetic Linear Contactless

Displacement

Permanent magnetic linear contactless displacement

(PLCD) sensors use the change of induction of a

locally saturated soft magnetic core. Even though it

was introduced in the 1980s this principle is restricted

to a few applications.

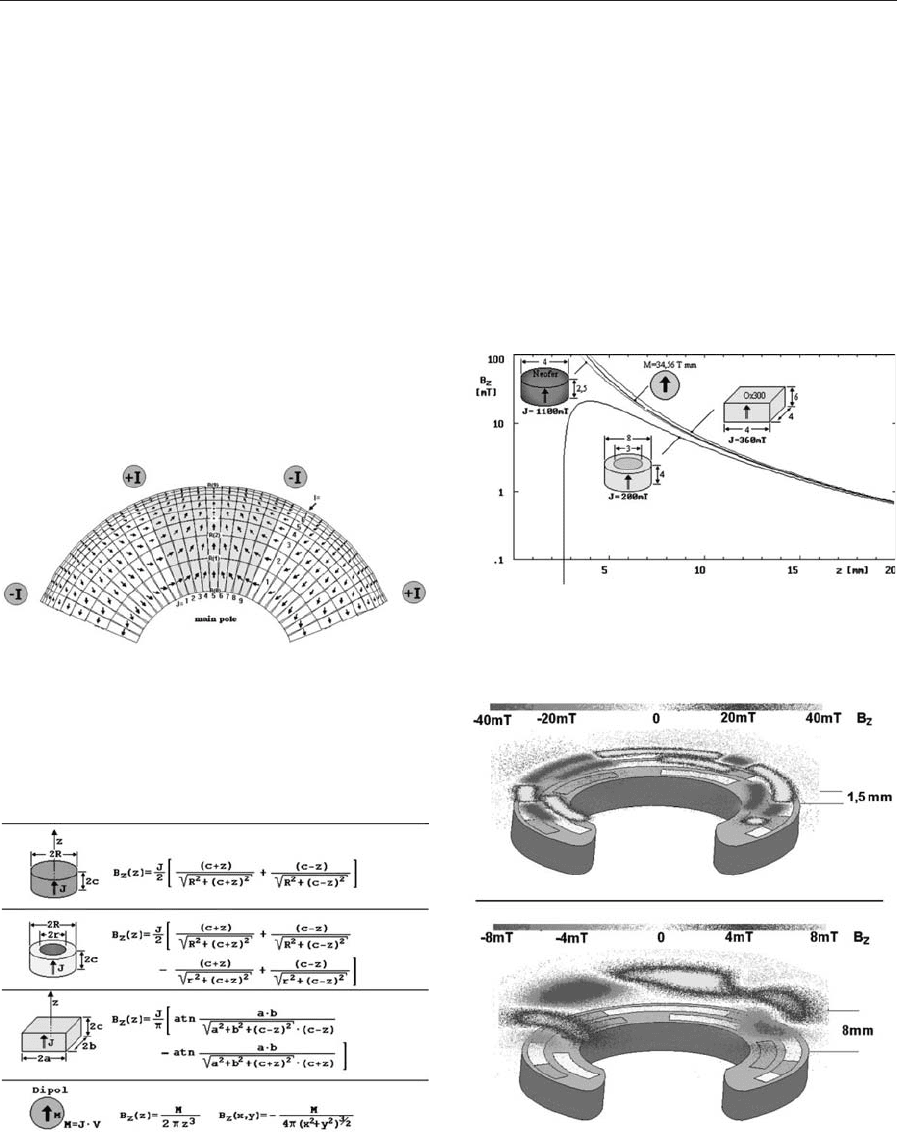

2. Field Design for Sensor Applications

Most of the traditional methods (e.g., finite element

method, FEM; finite difference method, FDM; and

boundary integral method, BIM) to calculate mag-

netic fields are not appropriate for the design of con-

figurations in sensor applications. On the one hand

the open magnetic circuit of a singular permanent

magnet does not require complicated numeric calcu-

lations for simply shaped magnets like rods or bar

magnets. The field of these magnets can be calculated

analytically. On the other hand most applications

work with multipole magnets for which the calculated

field depends greatly on the magnetic model of the

magnet. In these cases it is necessary to take into

account that a multipole magnetized magnet or, even

more complicated, a multipole oriented anisotropic

magnet has different magnetic material properties

and direction of magnetization in each point within a

magnet.

Traditional models in which the magnet is homo-

geneously magnetized in one direction are no longer

Figure 2

Schematic view of angular measurement with MR

sensors.

1038

Permanent Magnets: Sensor Applications

applicable. It is thus necessary to calculate the mag-

netic properties and the magnetization direction

within each element of the permanent magnet from

the circumstances during production or magnetiza-

tion. The melt flow orientation simulation (MFOS)

used to calculate the resulting magnetic field, there-

fore, consists of two analyzing steps. In a first step the

magnetic field of the production tools are evaluated

using conventional numerical methods. From the re-

sulting field the distribution of magnetic material

properties and the state of magnetization can be de-

duced for each point within the permanent magnet.

In a second analysis these values are used to calculate

the magnetic field that is produced by the final per-

manent magnet.

With this method crucial magnetic properties like

the steepness of the transition between a north and a

south pole or the irregular switching patterns or spe-

cial magnetic shapes can be designed on the computer

and can be compared to the required values without

changing any dimension of the magnet. This method

is demonstrated in Fig. 3.

2.1 Axially Magnetized Permanent Magnets for

Sensors

For the easy case of simply shaped magnets magnet-

ized in one direction the field of bar-shaped, disc-

shaped, or ring-shaped magnets can be calculated

analytically by the formulas shown in Fig. 4. All these

fields approach the dipole characteristic at larger dis-

tances as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 4

Analytical field of simply shaped permanent magnets.

Figure 5

Field profile of the magnets in Fig. 4.

Figure 3

Principle of MFOS. The orienting field (from coil þI,

I) is calculated and the actual magnetization state in

each element of the oriented magnet is simulated to

calculate the resulting field.

Figure 6

Field 1.5 mm and 4 mm above an irregularly magnetized

permanent magnet.

1039

Permanent Magnets: Sensor Applications