Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

flux density arising from this approximation are usu-

ally no more than a few percent.

Permanent magnet structures have been devised to

generate fields that are uniform, nonuniform, or time

varying.

1. Uniform Fields

It is not quite obvious that a permanent magnet can

be used to generate a uniform field, as the magnetic

field produced by a small bar magnet or point dipole

of moment, m (A m

2

), is nonuniform and anisotropic

as shown in Fig. 2(a). This field at a general point

r(r, y, f), relative to the axis of the dipole is given in

polar co-ordinates as

H

r

¼ 2mcos y=4pr

3

; H

y

¼ msin y=4pr

3

; H

f

¼ 0 ð2Þ

Both the magnitude and direction of H depend on

r(r,y,f). Nonetheless, a uniform field may be

achieved over some region of space by assembling

segments of magnetic material, each magnetized in a

different direction, such that their individual contri-

butions combine to yield a field which is uniform in

some confined region.

One approach is to build the structure from long

segments whose fields approximate those of line di-

poles of length, L, and dipole moment, l (A m), per

unit length. The field due to such a line dipole, in the

limit of infinite length, is given by

H

r

¼ lcos y=2pr

2

; H

y

¼ lsin y=2pr

2

; H

f

¼ 0 ð3Þ

Thus the magnitude of H,

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ðH

2

r

þ H

2

y

þ H

2

f

Þ

r

, at a dis-

tance, r, from each segment is actually independent

of y, while its direction everywhere makes an angle,

2y, with the orientation of the magnet as shown in

Fig. 2(b).

By assembling a long, cylindrical magnet with a

hollow bore from many individual segments, it is

possible to create a field which is uniform within the

bore. By choosing the orientation of each segment

appropriately, their individual fields will all add at the

center of the bore. Such segments can be assembled

according to many different prescriptions. Some de-

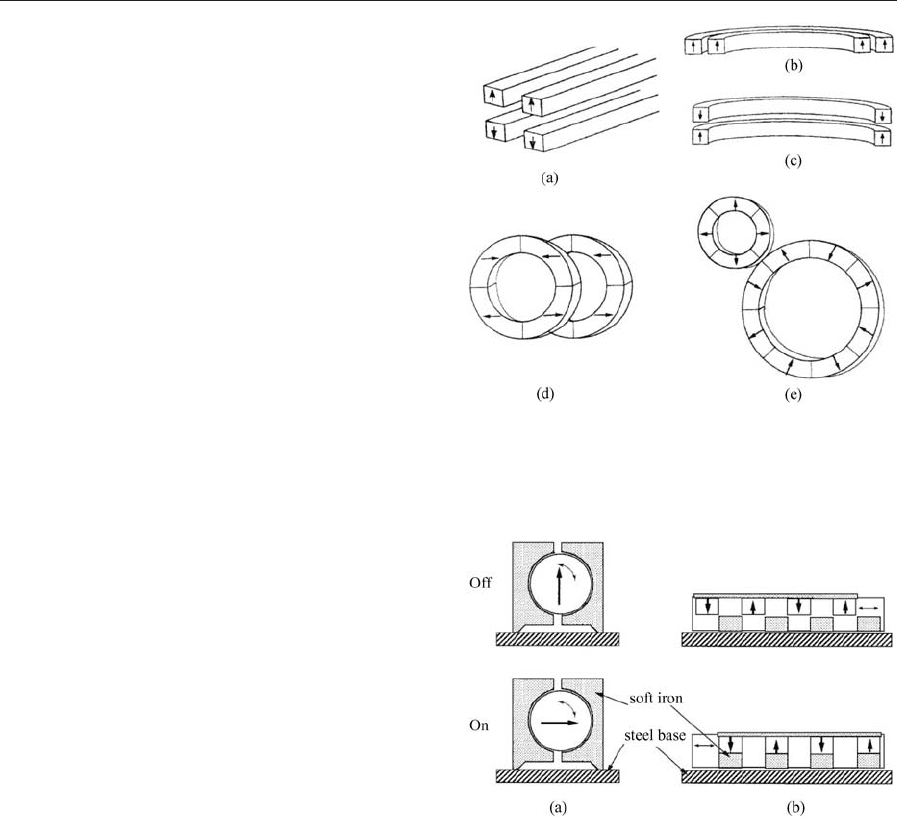

signs are shown in Fig. 3. The efficiency, e, of a par-

ticular cylindrical magnet structure generating a

uniform field in an airgap of cross-section, A

g

, is de-

fined as

e ¼ K

2

A

g

=A

m

ð4Þ

where A

m

is the magnet cross-section and K (Eqn. (1))

is now independent of r. A reasonably efficient struc-

ture has eE0.1. The theoretical limit on e is 0.25

(Jensen and Abele 1996).

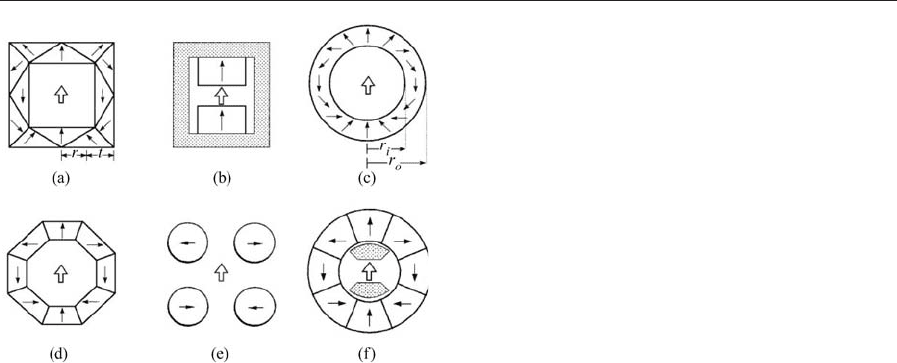

In the transverse field design shown in Fig. 3(a), the

outer surface is an equipotential with no perpendic-

ular stray field outside the surface and the flux density

in the airgap is 0.293B

r

provided t/r ¼O21. Multi-

ples of this field can be obtained by nesting similar

structures, each with the same t/r ratio, one inside the

other. These designs find application in nuclear mag-

netic resonance imaging (MRI). Highly homogene-

ous fields (better that one part in 1 10

5

) are required

for NMR applications. The generated fields must be

shimmed with small magnets or pieces of soft ferro-

magnetic material in order to meet this specification.

Also popular for NMR applications is the design

shown in Fig. 3(b), which consists of two flat cuboid

magnets and a soft iron return path (such a return

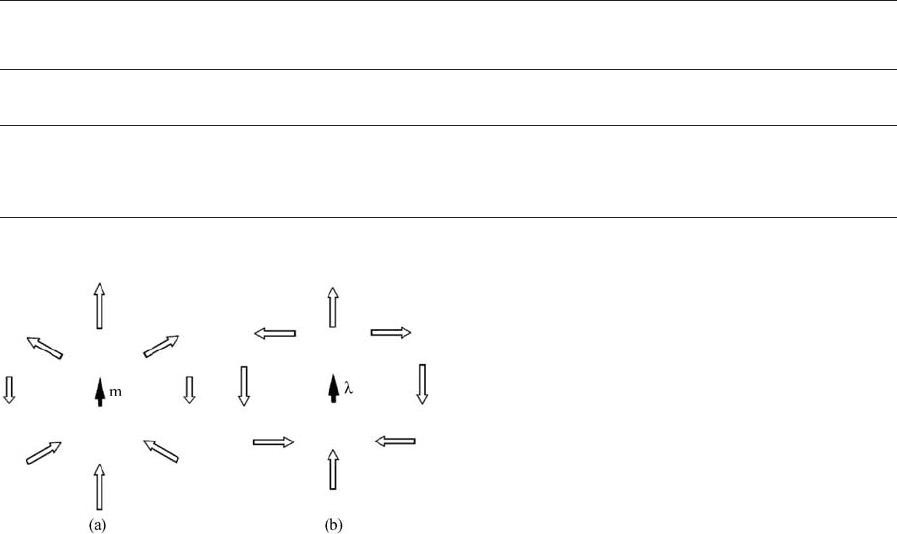

Figure 2

Comparison of the magnetic field pattern produced by

(a) a point dipole with moment m and (b) a line dipole

with moment l per unit length.

Table 1

Properties of typical oriented sintered ferrite and rare earth magnets.

Compound

T

C

H

a

J

r

H

c

(BH)

max

T

max

(1C) (MA m

1

) (T) (MA m

1

) (kJ m

3

)(1C)

BaFe

12

O

19

450 1.1 0.41 0.27 34 300

SmCo

5

720 32 0.88 1.70 150 250

Sm

2

Co

17

827 5.1 1.08 0.80 100 350

Nd

2

Fe

14

B 312 6.1 1.28 1.00 300 150

1010

Permanent Magnet Assemblies

path is often referred to as a yoke). Permanent mag-

net flux sources supply fields of order 0.3 T in whole-

body scanners for medical imaging. NMR spectro-

meters with permanent magnets flux sources are also

beginning to be used for quality control in the food,

polymer, and construction industries.

Figure 3(c) illustrates another design, known as the

Halbach cylinder or dipole ring, where the direction of

magnetization at any point in the cylinder is at 2y

from the vertical axis, and its magnitude remains

constant at all points. In the case of a cylinder of

infinite length, this configuration yields a uniform

magnetic field in the y direction within the cylinder

bore. The flux density in the airgap is given by Eqn.

(1) with

K ¼ ln ðr

o

=r

i

Þð5Þ

where r

i

and r

o

are the inner and outer radii of

the cylinder, respectively. Unlike the structure of

Fig. 3(a), the radii, r

i

and r

o

, can take any values

without creating a stray field outside the cylinder.

In practice a continuously varying magnetization

pattern is not easily achieved. A more common ap-

proach is to approximate the ideal configuration with

a finite number, N, of uniformly magnetized segments

as illustrated in Fig. 3(d) for N ¼8. In this case, the

field is reduced by a factor, [sin(2p/N)]/(2p/N), which

is included on the right-hand side of Eqn. (5). How-

ever, cylinders with as few as eight segments can still

generate 90% of the ideal field.

As a further approximation to the ideal design, the

cylinders are never infinitely long; their length, z,is

typically comparable to their diameter. The geomet-

rical constant, K, in Eqn. (4) is further reduced by an

amount (Zijlstra 1985)

DK ¼ðz=2Þ½1=z

o

1=z

i

þln ððz þ z

o

Þ=ðz þ z

i

ÞÞ ð6Þ

where z

o

¼(z

2

þr

o

2

)

1/2

and z

i

¼(z

2

þr

i

2

)

1/2

.Forexam-

ple, the flux density at the center of an octagonal cylin-

der with r

i

¼12 mm, r

o

¼40 mm, and length 80 mm

made of a grade of Nd–Fe–B having B

r

¼1.20 T is

actually 1.25 T, compared to the value of 1.44 T cal-

culated from Eqns. (1) and (5). Note that the flux in

the airgap exceeds the remanence in a circuit which

uses no iron, which illustrates the idea of magnetic flux

concentration.

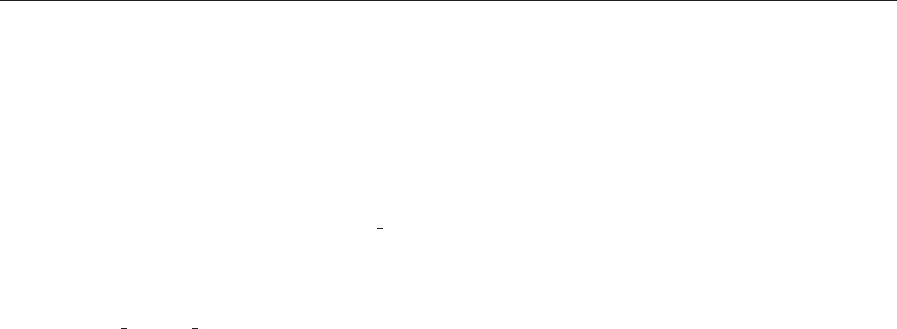

These cylindrical structures are useful for pro-

ducing fields in bores ranging in diameter from a few

millimeters to several hundred millimeters. Large

structures, like that shown in Fig. 4, are used for

industrial-scale materials processing and space-based

experiments.

Soft iron can be introduced into a permanent mag-

net circuit either to provide a return path for the flux

(Fig. 3(b)), or to concentrate the flux in the airgap

(Fig. 3(f)), thereby creating a larger uniform field

in a smaller volume. The field generated by the per-

manent magnet structure should be sufficient to

saturate the soft segments. Pure iron (J

s

¼2.15 T) or

permendur (J

s

¼2.43 T) may be used. In no case

can the additional flux density exceed the polarization

of the soft material, and in typical structures it will

only be a fraction of this value, depending on the

segment shape.

Assemblies composed of pairs of magnetized

wedges allow great flexibility in the shape of the

cavity while offering efficiencies comparable to those

of Halbach cylinders (Jensen and Abele 1999).

A different simplification of the basic structure uses

transversely magnetized cylindrical rods, as shown in

Fig. 3(e) (Coey and Cugat 1994). This allows both

longitudinal and transverse access to the cavity. The

geometrical constant at the center for a set of n rods,

which are just touching, is

K ¼ðn=2Þsin

2

ðp=nÞð7Þ

By increasing n, the central region in which the field is

uniform is enlarged, but the magnitude of the field

itself is reduced.

Uniform fields can also be generated in spherical

cavities using the same principles as for cylindri-

cal cavities (Leupold 1996). A uniform field is gen-

erated in a spherical cavity when the magnitude of

the polarization of a volume element in a hollow

spherical magnet structure is kept constant, but its

orientation varies as (2y,f) where (r,y,f) are its polar

Figure 3

Cross-sections of some permanent magnet structures

that generate a uniform magnetic field in the airgap in

the direction indicated by the hollow arrow. The

magnets are unshaded, with an arrow to show the

direction of magnetization. Shaded material is soft iron.

1011

Permanent Magnet Assemblies

coordinates. The resulting geometric constant is

K ¼ð4=3Þln ðr

o

=r

i

Þð8Þ

The field is one-third higher than for a Halbach cyl-

inder of comparable dimensions. Access to the field is

by diametral holes bored into the central space, which

do not perturb the field significantly provided their

radius is less than r

i

/4. An example is illustrated in

Fig. 5.

The upper limit to the fields that can be generated

using permanent magnets is about 5 T. This is set in

part by the coercivity of the material, as the vertical

segments in Fig. 3 are subject to a reverse H-field

equal to the field in the bore. But there is also a

practical size limitation imposed by the exponential

increase in dimension of Eqn. (5). Admitting a ma-

terial existed with B

r

¼1.5 T and m

o

H

c

¼5 T, the out-

er diameter required to achieve 5 T in a 25 mm bore

would be 700 mm. Such a structure of 400 mm in

height would weigh about 1 t.

2. Nonuniform Fields

The ability of rare-earth permanent magnets to gen-

erate complex flux patterns with rapid spatial varia-

tion (rB4100 Tm

1

) is unsurpassed by any

electromagnetic device. The solenoid needed to gen-

erate a field equivalent to that of a long magnet with

JB1 T, would require an Amperian surface current

of about 800 kAm

1

. Whether resistive or supercon-

ducting, it would have to be several centimeters in

diameter in order to accommodate the requisite am-

pere-turns. No such limitations exist for permanent

magnet dimensions.

The cylindrical configurations of Fig. 3 may be

modified to produce a variety of inhomogeneous

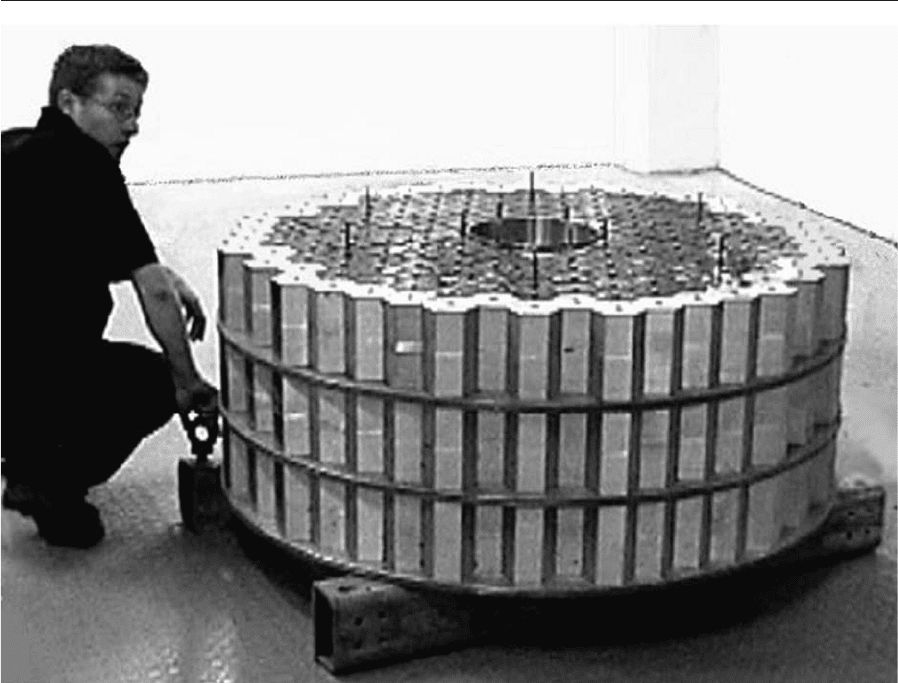

Figure 4

A large permanent magnet structure producing a field of 1 T in a bore of diameter 250 mm (photo by courtesy of

Magnetic Solutions Ltd).

1012

Permanent Magnet Assemblies

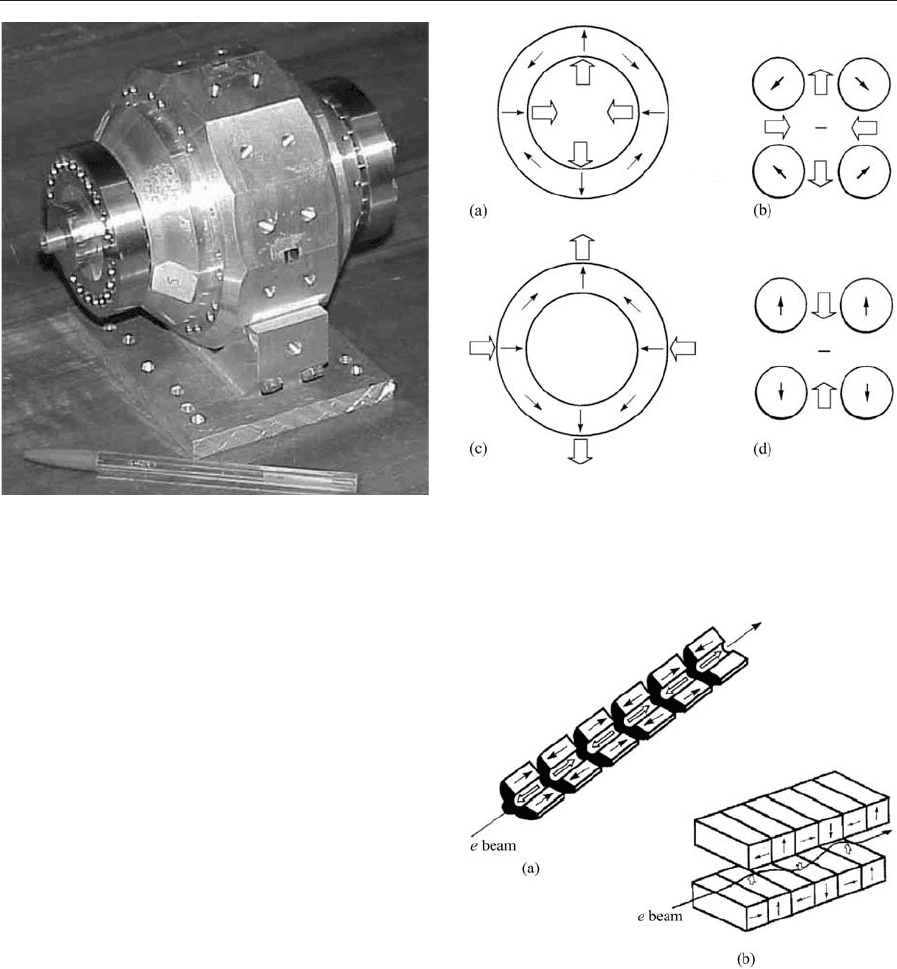

fields. Some examples are shown in Fig. 6. Multipole

fields such as quadrupole fields are particularly useful

for charged-particle beam control (Halbach 1980).

Various multipole fields are generated by having the

orientation of the magnets in the ring vary as (1 þ

(n/2))y, where n ¼2 for a dipole field (Fig. 3(c)), n ¼4

for a quadrupole field (Fig. 6(a)), n ¼6 for a hexapole

field and so on. The field at the center of the quad-

rupole is zero, but whenever the particle beam devi-

ates it experiences an increasing field which causes its

trajectory to curve back to the center. A simplified

four-rod structure, which also produces a quadrupole

field, is shown in Fig. 6(b).

A different type of permanent magnet structure cre-

ates an inhomogeneous magnetic field along the axis of

the magnet, which may be the direction of motion of a

charged particle beam. Microwave power tubes such

as the travelling wave tube are designed to keep the

electrons moving in a narrow beam over the length of

the tube and focusing them at the end while coupling

energy from an external helical coil. Originally this was

achieved by applying a uniform axial field from a re-

sistive solenoid, but the design with permanent mag-

nets focusing by a periodic axial field in Fig. 7(a) is just

as effective, and represents a great saving in weight

and power when SmCo

5

magnets are used.

One period of the structure in Fig. 7(a) generates

an axial gradient field, also known as a cusp field.

Uses of these fields include the stabilization of molten

metal flows.

Insertion devices for generating intense beams

of hard radiation (UV and x-ray) from energetic

Figure 7

Permanent magnet structures that create spatially

varying magnetic fields for particle beam control.

(a) A microwave power tube and (b) a wiggler magnet

for synchrotron radiation.

Figure 5

A spherical permanent magnet structure that produces a

field of 4.5 T in a spherical cavity of diameter 2 mm

(after Cugat and Bloch 1998).

Figure 6

Cross-sections of some permanent magnet structures

that generate nonuniform magnetic fields: (a) and (b) a

quadrupole field, (c) an external quadrupole field and,

(d) a field gradient.

1013

Permanent Magnet Assemblies

electron beams in synchrotron sources use a periodic

transverse field. These devices are known as wigglers,

since they cause the electrons to travel in a sinuous

path. Similar assemblies are used in free-electron

lasers. A design, which includes segments alternately

magnetized in parallel and antiparallel directions to

concentrate the flux, is shown in Fig. 7(b).

A variant of the normal multipole Halbach con-

figuration is the external Halbach configuration

where the orientation varies as (1(n/2))y. The mul-

tipole field is then produced outside the cylinder. The

case of n ¼4 (illustrated in Fig. 6(c)) produces a

quadrupole field outside the cylinder and zero field

inside. The external Halbach designs are useful for

the rotors of permanent magnet electric motors.

Other arrangements of cylindrical magnets

(Fig. 6(d)) produce a uniform magnetic field gradi-

ent along a particular direction. Field gradients are

especially useful for exerting forces on other magnets,

or on paramagnetic or diamagnetic material. The

force on a magnet of moment, m,isF ¼r(m.B)

whereas the expression for a nonferromagnetic ma-

terial is F ¼(1/2m

0

)wVrB

2

, where V is the sample

volume and w is the susceptibility. Field gradients of

the order of 100 Tm

1

producing separation forces of

the order of 1 10

8

Nm

3

are used in open gradient

magnetic separators to sort ferrous and nonferrous

scrap or select minerals from crushed ore on the basis

of their magnetic susceptibility.

Some magnetic levitation schemes exploit the

nonuniform fields produced by permanent magnets.

Diamagnetic material can be levitated against gravity

when rB

2

is of the order of 100 T

2

m

1

, which can be

achieved with permanent magnets in volumes of the

order of 1 mm

3

. A magnet can remain suspended in

the vertical field gradient of another magnet provided

it lies between two horizontal diamagnetic plates.

Many types of contactless bearings and couplings

use permanent magnet structures (Yonnet 1996). The

linear bearing illustrated in Fig. 8(a) provides levita-

tion along a track, but lateral constraint of the sus-

pended member is required. It is impracticable to

equip a great length of track with permanent mag-

nets. Thus, levitation of vehicles may be provided by

repulsion from eddy currents generated in a track of

metal plates, or by attraction of the magnets on the

vehicle to a suspended iron rail. The simplest rotary

bearings are made of two ring-shaped magnets in re-

pulsion. Some configurations (Fig. 8(b)) provide ra-

dial restoring force provided the axis is prevented

from shifting or twisting. Others support a load in the

axial direction (Fig. 8(c)), but must be prevented

from moving in the radial direction. Magnetic bear-

ings are simple, cheap, and reliable. They are best

suited to high-speed rotary suspensions as in fly-

wheels or turbopumps.

Figure 8(d) shows the design of a simple rotary

coupling and Fig. 8(e) is a magnetic gear. These are

useful for transmitting motion across the wall of a

chamber operating in vacuum or in an aggressive en-

vironment. Forces in bearings and couplings depend

quadratically on the remanence of the magnets, so it

is advantageous to select material with a large polar-

ization and a large coercivity, in case of slippage.

Torques of the order of 10 Nm may be achieved in

couplings a few centimeters in dimension.

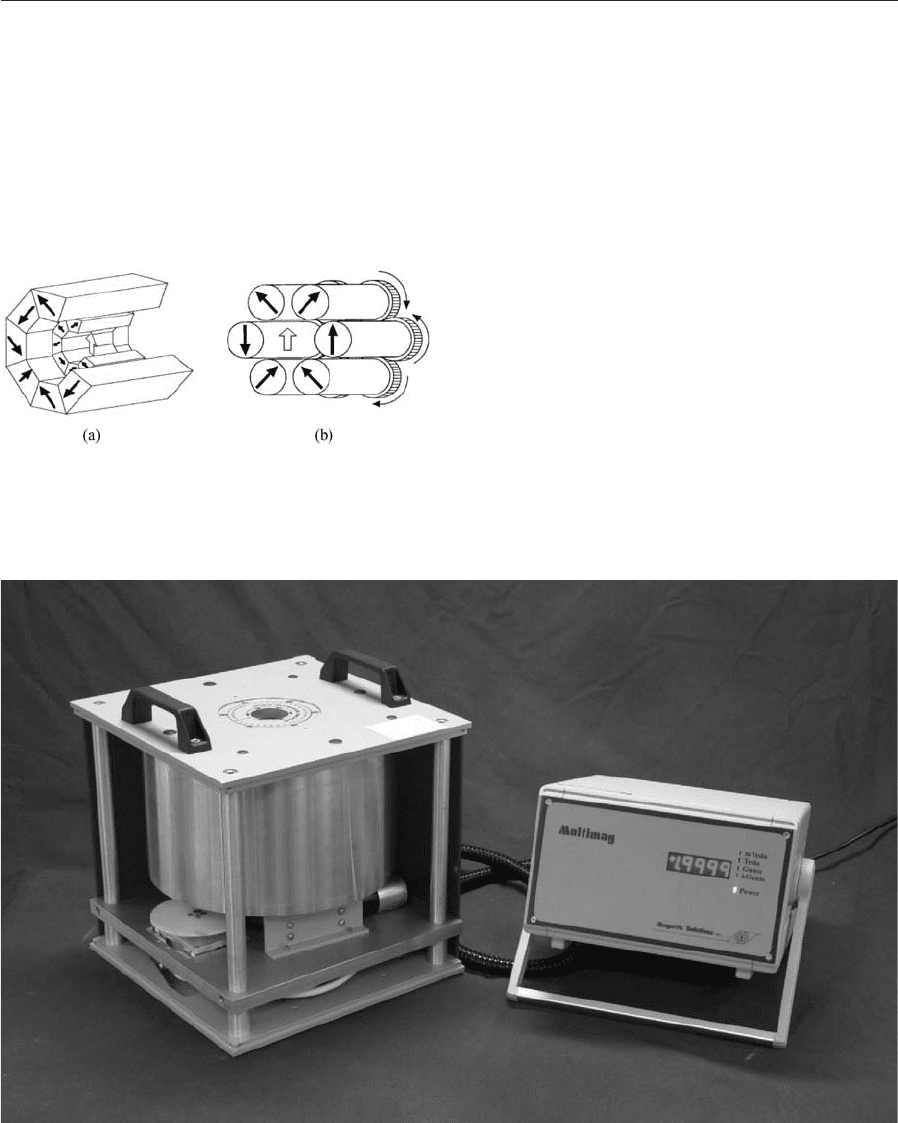

3. Variable Fields

Fields can be varied by changing the airgap, or by

some movement of the magnets in a structure with

respect to each other. The working point is displaced

Figure 8

Some magnetic bearings and couplings: (a) is a linear

bearing, (b) and (c) are rotary bearings, (d) is a rotating

coupling, and (e) is a magnetic gear.

Figure 9

Two designs for switchable magnets.

1014

Permanent Magnet Assemblies

as the magnets move. A simple type of variable flux

source is a switchable magnet (Fig. 9). These are of-

ten used in holding devices, where a strong force is

exerted on a piece of ferrous metal in contact with the

magnet. The working point shifts from the open cir-

cuit point to the remanence point where H ¼0 as the

circuit is closed. The maximum force that can be ex-

erted at the face of a magnet of area A

m

, where the

flux density is B

m

,isA

m

B

m

2

/2m

0

. Forces of up to

40 N cm

2

can be achieved for B

m

¼1T.

Simple force applications in catches and closures

consume large amounts of sintered ferrite. Polymer

bonded ferrite magnetized in strips of alternating po-

larity with a pitch of about 2 mm is widely used for

fixing signs and light objects to steel panels.

To create a variable uniform field, two Halbach

cylinders of the type shown in Fig. 3(d) each with

the same radius ratio can be nested one inside the

other, as shown in Fig. 10(a) (Leupold 1996). Then

by rotating them through an angle,7a, about their

common axis, a variable field, 2cosaJ

r

ln(r

o

/r

i

), is

generated. There would be no torque needed to rotate

two ideal Halbach cylinders, but in practice some

torque arises from the segmented structure and end

effects (Nı

´

Mhı

´

ocha

´

in et al. 1999).

Another solution is to rotate the rods in the device

of Fig. 3(e), as demonstrated in Fig. 10(b) (Cugat

et al. 1994). By gearing a mangle with an even num-

ber of rods so that the alternate rods rotate clock-

wise and anticlockwise through an angle, a, the field

varies as B

max

cos a. Further simplification is pos-

sible with a magnetic mirror, a horizontal sheet of

soft iron containing the axis of symmetry that pro-

duces an inverted image of the magnets, halving the

number of rods required. The torque needed to vary

the field in a mangle increases with a decreasing

Figure 10

Structures for producing continuously variable magnetic

fields. (a) A nested pair of Halbach cylinders and (b) a

rotating mangle.

Figure 11

A 2.0 T permanent magnet flux source based on the structure of Fig. 10(a) (photo by courtesy of Magnetic Solutions

Ltd).

1015

Permanent Magnet Assemblies

number of rods. A movable axial field gradient can

be achieved with nonuniformly magnetized rods

(Gro

¨

nefeld 1998).

These permanent magnet variable flux sources are

compact and particularly convenient since they can

be driven by stepping or servo-motors and they have

none of the high power and cooling requirements of a

comparable electromagnet. For example, the flux

source illustrated in Fig. 11 uses 20 kg of Nd–Fe–B

magnets of the design shown in Fig. 10(a) to generate

fields up to 2.0 T in a 25 mm bore. Large rotating or

alternating fields can be generated by continuously

rotating the magnets. Permanent magnet variable flux

sources are expected to displace resistive electromag-

nets to generate fields of up to about 2 T, but they

cannot compete with superconducting solenoids in

the higher field range.

4. Concluding Remarks

Permanent magnet structures are well suited to gene-

rate uniform fields, which are static or variable, as

well as multipole field patterns and field gradients

with rapid spatial variation. The advantages of per-

manent magnets are their compactness and energy

efficiency—no power supplies or cooling systems are

required. Their limitations lie in the maximum fields

that they can generate which are determined by the

remanence and coercivity of existing permanent mag-

net materials. Remanences of currently available

grades of rare-earth magnets are in the range

0.9–1.4 T. There is little prospect that future materials

development will extend the upper limit beyond 2 T.

The field produced by any permanent magnet

structure scales with remanence from Eqn. (1). De-

signs with KB1 are compact and efficient, and can

achieve flux concentration, but designs with K41.5

are inefficient in the sense that the ratio of the volume

of the magnet to the volume of the cavity increases

exponentially with B

g

.

The practical limit to the fields that can be gener-

ated with permanent magnets is about 5 T. For fields

in the range 2 mT to 2 T, a permanent magnet as-

sembly is often the best solution. Fields variable in

both magnitude and direction are obtained by some-

how rotating the magnets, as in the nested Halbach

cylinder systems or in the magnetic mangle. In this

field range, permanent magnet flux sources are set to

replace the venerable iron-core electromagnet.

As regards spatially varying fields, static field

gradients, rB, of up to 100 Tm

1

or more can be

achieved with permanent magnets in very small vol-

umes. Here there is no electrical solution to rival the

Amperian surface currents associated with a magnet-

ization of order 1 MAm

1

.

See also: Magnetic Levitation: Materials and Pro-

cesses; Magnetic Materials: Domestic Applications;

Permanent Magnets: Sensor Applications; Super-

conducting Permanent Magnets: Potential Applica-

tions

Bibliography

Coey J M D, Cugat O 1994 Construction and evaluation of

permanent magnet variable flux sources. In: Manwaring C A

F, Jones D G R, Williams A J, Harris I R (eds.) Proc.13th

Int. Workshop on Rare Earth Magnets and their Applications.

Birmingham, UK, pp. 41–54

Cugat O, Bloch F 1998 4-Tesla permanent magnet flux source.

In: Schultz L, Mu

¨

ller K-H (eds.) Proc.15th Int. Workshop on

Rare Earth Magnets and their Applications. MAT-INFO,

Dresden, Germany, pp. 853–9

Cugat O, Hansson P, Coey J M D 1994 Permanent magnet

variable flux sources. IEEE Trans. Magn. 30, 4602–4

Gro

¨

nefeld M 1998 New concepts in magnetic couplings derived

from Halbach configurations. In: Schultz L, Mu

¨

ller K-H (ed.)

Proc. 15th Int. Workshop on Rare Earth Magnets and their

Applications. MAT-INFO, Dresden, Germany, pp. 807–14

Halbach K 1980 Design of permanent multipole magnets

with oriented rare earth cobalt material. Nucl. Inst. Meth.

169, 1–10

Jensen J H, Abele M G 1996 Maximally efficient permanent-

magnet structures. J. Appl. Phys. 79, 1157–63

Jensen J H, Abele M G 1999 Closed wedge magnets. IEEE

Trans. Magn. 35, 4192–9

Leupold H A 1996 Static applications. In: Coey J M D (ed.)

Rare-earth Iron Permanent Magnets. Oxford University

Press, pp. 381–429

Nı

´

Mhı

´

ocha

´

in T R, Weaire D, McMurry S M, Coey J M D

1999 Analysis of torque in nested magnetic cylinders. J. Appl.

Phys. 86, 6412–24

Skomski R, Cugat O 1999 Permanent Magnetism. IOP Pub-

lishing, Bristol, UK

Yonnet J-P 1996 Magnetomechanical devices. In: Coey J M D

(ed.) Rare-earth Iron Permanent Magnets. Oxford University

Press, pp. 430–51

Zijlstra H 1985 Permanent magnet systems for NMR tomo-

graphy. Philips J. Res. 40, 259–88

J. M. D. Coey and T. R. Nı

´

Mhı

´

ocha

´

in

University of Dublin, Ireland

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron

Experiments

The crystallographic and magnetic properties of

materials exhibiting hard magnet characteristics can

be simultaneously analyzed by the use of neutron

scattering techniques. After an introduction to the

different structural, microstructural, and magnetic

parameters that are determining factors for optimal

intrinsic and extrinsic magnetic properties, the main

principles of neutron scattering, both nuclear and

magnetic aspects, are discussed in detail in this

article. Specific techniques are reviewed, together

1016

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments

with pertinent examples underlining the advantages

of neutron scattering.

Modern, powerful hard magnetic materials are of

metallic type. They are based on compounds com-

bining the magnetic characteristics of transition

metals and rare-earth metals, mainly cobalt or iron

combined with samarium, neodymium, or praseo-

dymium. In the crystal structures of these magnetic

compounds, the densest sublattice (d elements) pro-

vides a high magnetization and supports strong

exchange forces, resulting in a high Curie tempera-

ture. As important is the less dense rare-earth metal

sublattice that couples ferromagnetically with cobalt

or iron in the case of the light 4f elements and which

provides strongly anisotropic crystal electric field

(CEF) parameters, forcing to a marked easy axis be-

havior of the magnetic structure (see Localized 4f and

5f Moments: Magnetism and Alloys of 4f (R) and 3d

(T) Elements: Magnetism).

In all cases, more than these two elements are

needed to stabilize the hard magnetic main phase

(e.g., boron in Nd

2

Fe

14

B, nitrogen in Sm

2

Fe

17

N, etc.)

or to stabilize a highly coercive microstructure (e.g.,

multiphase systems as in the complex Sm(Co–Fe–

Cu–Zr)

8.5

magnets) (see Rare Earth Magnets: Mate-

rials). Either the atomic long-range ordering that

defines the crystal structures or the microcrystalline

aspects of the multiphase systems must be measured

in combination with the magnetic structure ordering

parameters (strength and orientation of the moments,

crystal field terms, etc.) and critically analyzed before

the highest level of properties can be developed.

Many different techniques are used systematically to

obtain the best knowledge of both the intrinsic and the

extrinsic properties of the intermetallic or interstitially

modified materials showing potentially good magnetic

performances. These techniques are chosen specifical-

ly, over a wide range of analyses, to characterize bulk

magnets (material at gram and centimeter scales), to

check the micrometric to submicrometric range of

properties (multiphase structures, domain structure),

to study the impact of dense arrangements (atoms,

coordination) from the nanoscale to the bond scale, or

to perform spectroscopic analysis of the orbital

(ground) states. Indeed there are many more possible

investigation methods, tools, and techniques that can

be used to characterize magnetic materials. However,

because of wide application ranges, neutron scattering

techniques appear to be highly valuable for the sys-

tematic characterization of the crystal as well as the

magnetic ordering parameters, on the basis of the

typical and multipurpose aspects of the interaction of

neutrons with atoms and their magnetic moments.

1. Neutron Scattering, Sources, Principles, and

Characteristics

Two main types of generators have been developed

for the production of intense neutron beams

(typically 10

10

–10

14

neutrons s

1

). The so-called con-

ventional reactor is based on the continuous fission

process of

235

U nuclei (B 2 MeV) with an excess of

neutrons of about 1 for 2.5 emitted if a critical mass

of fissile core is used. In the pulsed type of source,

neutrons are produced from heavy atoms (Pb,

238

U,

etc.) by strongly accelerated (B 1 GeV) pulses of

protons (spallation source). For example, very short

pulses (100 ms) of 20–40 neutrons per proton are ra-

diated periodically (10 ms). In all cases, the neutron

energy (velocity) is moderated within appropriate

materials. Reactor-type neutron sources are installed

worldwide.

The most powerful one is the European HFR-ILL

at Grenoble, France. Only a few machines of the

pulsed type are operating (in the USA, the UK, Rus-

sia, and Japan), with ISIS at Didcot, UK, being the

most powerful one. In this article, rather than focus-

ing on the respective merits of each type of neutron

generator, the critical differences in the use of neu-

trons for scattering within materials are discussed.

From the Maxwellian shape of the energy spectrum

issued from the source, in most cases a monochro-

matic neutron beam has to be selected by using crys-

talline monochromators or by creating kinetically

controlled pulses by speed selectors (e.g., wheel-chop-

pers). The multifaceted nature of the neutron takes

advantage of the physical characteristics as expressed

in Table 1.

Owing to these fundamental equivalences, for a

neutron beam of wavelength l ¼1.8 A

˚

, i.e., suitable

for scattering in crystalline compounds (interatomic

distances of 1–2 A

˚

), the neutron speed is 2200 ms

1

and the energy is 25 meV, corresponding to an equiv-

alent temperature of 300 K. Hence, these neutrons

are called thermal neutrons. At low temperature

(TB20 K) a moderator placed close to the reactor

core allows for the use of so-called cold neutrons with

a longer wavelength of 30–50 A

˚

. A high-temperature

(T42000 K) target allows for neutrons with a shorter

wavelength of less than 0.4 A

˚

.

The first interaction of neutrons with matter

(which is not the most interesting one from the point

of view of magnetic properties) consists of a nuclear

Table 1

Relationships between the characteristic parameters of

free neutrons.

Wave vector: k (nm

1

); wavelength: l ¼2j/k (nm, A

˚

);

momentum: p ¼_k; celerity: v ¼(_/m)k (km s

1

)

Energy: E ¼(_

2

/2m)k

2

¼mv

2

/2 ¼5.2267v

2

¼(h

2

/2m)

(1/l

2

) ¼0.81799/l

2

1 meV ¼1.6022 % 10

22

J ¼11.6045 K ¼0.2418 %

10

12

Hz

Thermal neutron (300 K): celerity ¼2200 ms

1

;

energy ¼25 meV; wavelength ¼1.8 A

˚

1017

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments

resonance and capture phenomenon, represented by

an absorption cross-section, s

a

. Except for some iso-

topes (

113

Cd,

157

Gd,

164

Dy, etc.), for most elements

the corresponding cross-section remains negligible. It

should be noted that the absorption is minimal far

from the resonance energy.

The two main scattering processes of thermal neu-

trons in solid-state materials that exhibit magnetic

properties are of the dipolar type.

The first process is nuclear scattering. This results

from the interaction of the neutron spin, n

s

¼

1

2

, with

the nuclear spin, I. The corresponding nuclear po-

tential is effective at a distance of the same magnitude

as that of the nucleus dimensions. Two intermediate

scattering lengths, a

þ

and a

–

, are associated with the

final states I þ

1

2

and I

1

2

. Together they establish the

coherent part of the scattering length b

c

¼a

þ

(I þ1)/

(2I þ1) þa

(I)/(2I þ1) and the incoherent part

b

i

¼(a

þ

a

)/(2I þ1). Practically, the coherent scat-

tering process in combination with structured mul-

ticentered materials yields discrete intensities

depending on the structure factor that is determined

by the atomic arrangement. These scattering intensi-

ties can interfere constructively, whereas the incoher-

ent scattering, which has isotropically distributed

diffuse intensities, cannot interfere. However, con-

sidering the dynamic diffusion of a light element (e.g.,

hydrogen as a proton), incoherent scattering by this

particle can be analyzed using a time and position

resolving technique.

The second process is magnetic electron scattering.

This results from the interaction of the neutron spin

with the spin, s, and orbital, l (if any), vectors at-

tached to the electrons. It can be described in terms of

the total atomic spin, S, and orbital, L, components.

The diffusion length is f

M

¼2m/_

2

(M

n

4e) (M

e

4e),

where e is the unit vector and M

n

and M

e

are the

magnetic moments of the neutron and the electron,

respectively, along the scattering vector (e.g., perpen-

dicular to the diffraction plane). The magnetically

scattered amplitude strongly depends on the orienta-

tion of the easy magnetic axis in relation to the nor-

mal of the diffraction plane (in-plane vs. out-of-plane

components of the moments). If the magnetic field is

strong enough to align the moments along the scat-

tering vector, the magnetic contribution to diffraction

can vanish.

If the neutron beam polarization level is r

n

(e.g., as

diffracted on a ferromagnetic single-domain single

crystal), coherency effects can be observed between

both the nuclear and the magnetically scattered waves.

This can be expressed by the total cross-section:

s

t

¼ b

2

c

þ p

2

M

q

2

2b

c

p

M

q r

n

where p

M

is proportional to f

M

and q is the scattering

vector.

There are several important peculiarities to point

out. Because of the point-type potential of the

nuclear interaction, the nuclear cross-section of dif-

fusion results in a quasi-constant diffusion (Fermi)

length. Since it is a nuclear characteristic (isotope

characteristic), very large differences exist between

the elemental Fermi lengths, revealing marked con-

trasts, e.g., for crystal structure determination. Suc-

cessive d (and f) metals are different from each other

and, in the same manner, most of the interstitial light

elements are good scatterers. Table 2 compares se-

lected cross-section amplitudes (Sears 1984).

Contrary to the nuclear scattering, the magnetic

scattering related to the magnetic electron density, i.e.,

the magnetic scattering cross-section, decreases with

the momentum transfer, Q, well approximated by

Gaussian profiles (Brown 1992), which may reveal

localized to itinerant aspects of the electron density.

For a completely disordered moment distribution

(paramagnetic state with no short-range correlations),

independent of the initial polarization state of the

beam, a diffuse magnetic (incoherent) scattered inten-

sity is found that adds to the nuclear contribution.

For a polarized neutron beam, successive measure-

ments of the scattered intensity for two states of po-

larization (up and down, the scattering vector being

horizontal) allow one to determine very accurately the

spatial spin density, if the nuclear crystal structure is

known. It should be noted that, if the magnetic struc-

ture exhibits unpolarized components, a depolariza-

tion effect is induced that can be successfully adopted

in the polarization analysis technique to detect weak

deviations from ferromagnetism.

The scattering processes as described above are of

the elastic type (no energy exchange). Since the ki-

netic energy of thermal neutrons is of the same order

of magnitude as that of the excitation processes of

matter (phonons, atom diffusion, magnons, crystal

field levels, etc.), inelastic scattering experiments can

provide valuable information on the correlation en-

ergies or the dynamics of atom movements. Inelastic

scattering leads to a change (initial to final states) of

the neutron energy, where the opposite energy cor-

responds to the phonon or magnon frequency change

ho. Q ¼k

f

k

i

¼2jR þq allows one to localize scat-

tered neutrons with a typical intensity given by a

double differential (space and energy resolved) scat-

tering cross-section. Q is the scattering vector, R a

reciprocal lattice vector, q the wave vector of the

excitation, and k

i

and k

f

are the initial and final wave

vectors. For such purposes, an analyzer is placed

behind the sample to check the spatial and energy

dispersion profile.

2. Applications of Neutron Scattering to Hard

Magnetic Materials

Except for anomalously absorbing nuclei, the pene-

tration depth of neutrons is particularly large (a few

centimeters), several orders of magnitude larger than

1018

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments

for x rays (micrometers). It is worth noting that large

samples and thick-walled sample holders and vessels

can be used, for example, to investigate fundamental

as well as extrinsic magnetic properties, even those

sensitive to external pressure, high temperature,

corrosion, etc. Examples selected from the literature

are discussed below, in order to illustrate the multi-

ple applications of neutron scattering to magnetic

materials.

2.1 Crystal Structure Determination

(a) Powder diffraction

Neutron diffraction on powdered samples is a pow-

erful technique that allows in most cases for the de-

termination of the crystal structure of the compound

more easily than by using x-ray powder diffractome-

try, owing to the excellent contrast in the scattering

cross-sections, as shown in Table 2. For such pur-

poses, it is recommended to use a high-resolution

neutron diffractometer that consists of banks of a

large number of individual detectors equipped with

selective collimators. The crystal structure of

Nd

2

Fe

14

B, especially the position of the light boron,

was solved for the first time (Herbst et al. 1984) using

neutron diffraction on a powdered sample. Parallel to

this, the crystal structure was also solved by using

x-ray single-crystal four-circle diffractometry (Shoe-

maker et al. 1984, Givord et al. 1984). The location of

light hydrogen (deuterium) atoms inserted in four

types of adjacent tetrahedral sites in Y

2

Fe

14

BD

4.8

was

determined by means of a good-resolution position-

sensitive neutron detector (Fruchart et al . 1984).

The scheme of the successive filling of the sites, that

was found later to depend on the nature of the rare-

earth element, was determined using a geometrical

model that allowed the prediction of the maximum

hydrogen uptake. When the interstitial ternaries

R

2

Fe

17

X

x

(R ¼rare earth; X ¼C, N, H) were found

to exhibit potentially high magnetic performances,

neutron diffraction on powdered samples was the

unique technique to ascertain the position and the

stoichiometry (x) of the light element. From volu-

metric or barymetric gas absorption experiments, it

was suggested for a long time that particularly large

amounts of X elements (up to nine for hydrogen, up

to six for carbon and nitrogen) can be inserted into

the 2-17 metal lattice to improve the Curie temper-

ature, the magnetization, and other magnetic prop-

erties. From neutron diffraction experiments, it was

definitively shown that, at maximum, three carbon or

nitrogen and 5 ( ¼3 þ2) hydrogen atoms per formula

unit occupy well-defined 2R–4Fe octahedral sites,

Table 2

Absorption and scattering neutron cross-sections of selected elements or isotopes.

Element/isotope Z (x rays) PCT (%) s

a

(barns) b

c

(Fermi) B (Fermi)

1

H 1 99.985 0.33 3.74 25.21

2

H 1 0.015 0.33 6.67 2.04

10

B 5 20 3837 0.1i(1.06) 4.7 þi(1.23)

11

B 5 80 0.005 6.65 1.31

C 6 0.003 5.65 0.0

N 7 1.90 9.38 0.0

Mn 25 13.3 3.73 1.79

Fe 26 2.56 9.54 0.0

Co 27 17.18 2.50 6.2

Ni 28 4.49 10.3 0.0

58

Ni 28 68.27 4.6 14.4 0.0

80

Ni 28 26.10 2.9 2.8 0.0

Cd 48 2520 5.1i(0.7) 0.0

Pr 59 11.5 4.45 0.36

Nd 60 50.5 7.69 0.0

Sm 62 5670 4.2i(1.58) 0.0

149

Sm 62 13.9 40140 24i(11.2) 28i(9.84)

Gd 64 48890 9.5i(13.59) 0.0

157

Gd 64 15.7 254000 11i(70.6) 26i(54.7)

Tb 65 23.4 7.38 0.17

Dy 66 940 18.9i(0.26) 0.0

164

Dy 66 28.1 2650 49.4i(0.74) 0.0

Ho 67 64.7 8.08 1.7

Th 90 7.37 9.84 0.0

Source: Sears (1984).

1019

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments