Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

two extra hydrogen atoms occupying smaller 4R–3Fe

tetrahedral sites (Isnard et al. 1990).

This was confirmed by Koyama and Fujii (2000)

for N

2

Fe

17

N

3

. It is also of interest to analyze the cell

parameter expansion, not only on light element in-

sertion but also when other elements are substituted

for iron in order to modify the bond lengths. The

location of these elements as a function of their con-

centration provides interesting arguments for a better

understanding of the modification of the bulk mag-

netic characteristics that are volume dependent. This

has been systematized for titanium, cobalt, manga-

nese, gallium, silicon, etc., establishing reliable

schemes of substitution (Mishra et al. 1996).

For some resonantly absorbing elements (dyspro-

sium), either the use of a two-wall cylindrical sample

holder at l ¼12.5 A

˚

or the use of very short wave-

lengths (l ¼0.5 A

˚

) gives the most convenient condi-

tions to record rather good data on powdered

samples, e.g., gadolinium or samarium.

(b) Single-crystal diffractometry

The most precise technique to use for crystal struc-

ture determination is four-circle diffractometry.

However, this requires rather large single crystals.

Spheres of 1.5–2.5 mm in diameter of R

2

Fe

14

B

(R ¼Y, Nd, Ho, Er) have been cut by spark erosion

from large crystals and systematically studied by

neutron diffraction. Precise information about the

atomic positions and interatomic distances has been

obtained for these dense iron compounds (Wolfers

et al. 1996). Ancillary equipment can be used to per-

form experiments under special external conditions,

e.g., very low or high temperatures, uniaxial stress, or

high pressures.

(c) Small-angle and diffuse scattering

The small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) technique

using long neutron wavelengths (10–20 A

˚

) allows one

to investigate intermediate-size domains in the struc-

ture, for example, as formed by segregation effects.

Only a few examples using SANS have been reported,

e.g., the segregation rates of cobalt and copper in

Sm(Co–Cu)

5

alloys that markedly influence the in-

trinsic and extrinsic hard magnetic properties of the

binaries. In the RFe

5

Al

7

series, a clustering tendency

of iron is evident from classical powder diffraction

experiments by the analysis of diffuse scattering phe-

nomena, since the atomic clustering influences the

magnetic correlation scheme (Scha

¨

fer et al. 1994).

2.2 Magnetic Structure Determination

Neutron powder diffraction is a convenient technique

for the measurement of the local magnetic moment

characteristics. The higher the counting rate, the

better are the refined values. For such a purpose, an

instrument typically has a position-sensitive detector

(PSD) providing a high counting rate at a sufficiently

long wavelength that enables one to record the sig-

nificant magnetic source signal within the aperture of

the detector array. At HFR-ILL, Grenoble, and at

LLB, Saclay, there are optimized instruments allow-

ing one to measure diffraction patterns with a high

statistic in the time range of minutes up to a few

hours. It is recommended to record at least one high-

resolution diffraction pattern in a large range of Q

spacings using a dedicated diffractometer that pro-

vides precise crystal structure parameters. Moreover,

the excellent counting rate of the banana-type PSD

allows one to perform time- and temperature-

resolved experiments in order to determine accu-

rately the changes in the magnetic moments, e.g., for

R

2

Fe

14

B(R¼Nd, Ho, Er), as well as for RFe

12–x

T

x

(R ¼Dy) in the range of the Curie temperature or

possible spin reorientation temperatures (SRTs).

When single crystals are available, the four-circle

technique remains by far the best for detailed crystal

and magnetic structure determinations, as demon-

strated for the R

2

Fe

14

B series (R ¼Y, Nd, Ho, Er)

(Wolfers et al. 1996). After appropriate corrections

(e.g., absorption or multidomain corrections), precise

fittings to the data (several thousand recorded Bragg

peaks) lead to detailed pictures of almost ferromag-

netic but noncollinear magnetic structures accompa-

nied by the small-atom displacements (and crystal

symmetry lowering) related to the important magne-

toelastic forces existing in these compounds.

Another method, polarized neutron diffraction

(PND), can be used to investigate the magnetic struc-

ture of truly ferromagnetic and very large single

crystals, e.g., Y

2

Fe

14

B (Givord et al. 1985). With this

technique, and in the case where the data collection

statistics are good enough, a Fourier transformation

allows one to plot spin density projections, thus re-

vealing local but weak magnetic polarization effects

or temperature-induced changes of density moment

setting on cobalt atoms in ThCo

5

(Givord et al.

1977).

Using thermal neutrons it seemed impossible to

analyze the magnetic structures of one of the arche-

typal magnetic compounds, SmCo

5

. However, using

short wavelengths of 0.4–0.5 A

˚

, in order to reduce the

nuclear absorption, precise PND experiments have

allowed the calculation of the magnetic form factors

of cobalt and samarium, the latter being very differ-

ent at 4 K and 300 K: the samarium moment is much

smaller at room temperature than at low temperature

(Givord et al. 1979). Further analyses show that the

form factors of L and S type show quite different

radial shapes for samarium. Accounting for the op-

posite orbital and spin contributions in the magnetic

moment of samarium yields an anomalous thermal

behavior with a crossover temperature estimated as

350 K. Modeling of the appropriate Hamiltonian,

considering the large exchange forces and the mixed

1020

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments

CEF multiplets of the samarium ground state, allows

one to determine exchange and CEF parameters

from a fit to the experimentally obtained form

factors. Furthermore, the exchange field and the sec-

ond-, fourth-, and sixth-order CEF parameters have

been calculated, respectively, as 175725 K, 2007

50 K, 0750 K, and 50750 K (Givord et al . 1979),

which are in good agreement with values deduced

from magnetization experiments and corresponding

calculations.

For the parent compound YCo

5

, a PND study

has permitted the determination of the origin of a

very large magnetocrystalline anisotropy, which is

not related to the nonmagnetic yttrium but to one of

the two cobalt sites (Co

II

), which exhibits a partic-

ularly high orbital contribution and is attributed to

its peculiar and asymmetric environment (Schweizer

and Tasset 1980).

2.3 Magnetic Excitations

Dynamic excitation spectra have been recorded for

different series of intermetallics belonging to the dif-

ferent classes of hard magnetic materials. For the

R

2

Fe

14

B series of materials, inelastic neutron scat-

tering (INS) was first performed on powder samples

(Loewenhaupt et al. 1988). For R ¼Y and Ce, only

phonon scattering is identified. For R ¼Nd, Dy, and

Er, resonances of magnetic origin are observed. These

are attributed to magnon-like excitations for the lat-

ter two compounds, since they markedly increase

with temperature (dominant Zeeman field, negligible

CEF). For the neodymium compound, two well-

defined and equivalent peaks (22 meV and 36 meV)

are assigned to the two nonequivalent neodymium

sites in terms of CEF effects. From the thermal

dependence, it is concluded that the neodymium

moment corresponding to the larger CEF signature is

poorly affected by the SRT, contrary to the other

neodymium site that is sensitive to SRT conditions as

sharing the weakest CEF level. This approximate

model cannot be considered to agree well with the

accurate magnetic structure determination (Wolfers

et al. 1996) refined from single-crystal data collection.

Subsequent INS experiments on Nd

2

Fe

14

B single

crystals (Mayer et al. 1992) did not show the existence

of lines at 22–36 meV. However, low-energy lines

(magnon dispersion) were analyzed on the basis of

torque effects acting on the magnetic moments driven

by effective exchange and anisotropy fields. The

authors proposed a strong influence of long-range

interactions in relation to an itinerant character of

the iron magnetism.

The R

2

Zn

17

compounds are isotypic with the mag-

netic R

2

Co

17

compounds. However, owing to the

simplest magnetic situation (here only R is magnetic),

the CEF excitations were analyzed first (Garcia-

Landa 1994). In the low-energy region (o15 meV)

several peaks were confirmed to be of CEF origin;

then the noninteracting spins were described using

a pure CEF model. For R ¼Er, (T

SR

¼1.4 K,

T

N

¼1.6 K) a set of CEF parameters was determined,

of which the dominant one is the negative second-

order term of less than 2 K, thus agreeing with a

magnetically easy plane behavior.

Magnetic excitations have been investigated in de-

tail in some R

2

T

17

compounds (T ¼transition metal)

(Clausen and Lebech 1982). The spin wave dispersion

relationships have been interpreted with a linear spin

model comprising a Heisenberg exchange term and

single-ion CEF anisotropy terms. Experiments per-

formed on Dy

2

Co

17

single crystals using the IN8-ILL

spectrometer (Colpa et al. 1989) have been analyzed

using a complete Hamiltonian with respect to the

R–R exchange interaction, which is often considered

negligible if compared to the T–T and R–T ones.

Since there are some discrepancies between the as-

signment of a highly dispersive mode that is asso-

ciated with the Co–Co exchange forces, both the

exchange and the CEF characteristic energies have

been deduced. For Dy

2

Co

17

, the values are: J

TT

B

200 K, J

RT

B25 K, J

RR

B0.2 K, CEF

R

parameters

B28 to 6 K, and T-anisotropy parameter B6 K. They

are in good agreement with the high-field magnetiza-

tion fittings (Givord et al. 1977) as compared to those

obtained by NPD for SmCo

5

.

2.4 Atom Dynamics

The quasielastic neutron scattering (QNS) technique

based on space and time self-correlation of a single

nucleus, which is supposed to move within the com-

pound, is practically restricted to studying either the

motion processes of this nucleus (e.g., hydrogen) or

the fast rotation of some molecules. This becomes

possible owing to a very high incoherent scattering

length. For the present purposes, it can be used to

analyze the living time of a proton within interstitial

sites and the related energy of hopping. A typical ap-

plication could be the analysis of the diffusion mode

of protons, i.e., during either the hydrogen decrepi-

tation or the HDDR (hydrogen decomposition–

dehydrogenation–recombination) processes (diffusion,

nucleation, wall interface mechanisms, etc.) (see Mag-

nets: HDDR Processed). The analysis of the data

could be somewhat difficult owing to the rather large

unit cell and the multiple and different interstitial sites.

However, the questions concerning the diffusion

mechanisms have been partly solved, as explained

below.

2.5 Phase Transformation Analysis from Resolved

Diffraction Experiments

So far only structural and magnetic fundamental

trends of the main compounds forming magnet

1021

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments

materials have been considered. However, magnetic

properties are much improved by particularly fine-

designed microstructures resulting from well-defined

thermal or mechanical treatments. In situ neutron

diffraction experiments performed with PSD instru-

ments with high counting rates have allowed the de-

termination and optimization of chemical and

physical treatments leading to the best extrinsic prop-

erties. Some typical examples are given below.

Temperature- and time-dependent neutron diffrac-

tion experiments confirm the maximum hydrogen

uptake in the Nd

2

Fe

17

H

x

unit cell, and its distribu-

tion onto the two accessible sites (tetrahedral and

octahedral types). The preferential chemical attrac-

tion favors the larger and space repartited octahe-

drons (Isnard et al. 1990). The cell parameter

expansion is determined and the behavior of a crit-

ically short Fe–Fe distance is refined. A clear corre-

lation between the hydrogen occupation rates of

the sites is established, the corresponding changes of

the Fe–Fe distances and the nonlinear increase of the

Curie temperature have been attributed to an increase

of the exchange parameters.

Similar experiments performed with hydrides (de-

uterides were chosen to avoid the strong incoherent

scattering of hydrogen), as well as with carbides and

nitrides, allow the assertion of the existence of an

extended solid solution in the 2-17 and 1-12 hydride

and carbide phase diagrams and a two-phase be-

havior in nitrides (Fruchart et al. 1994).

Using a dedicated sample holder connected to a

hydrogen (deuterium) cylinder and gas pressure sen-

sors, time (kinetics), pressure level (or vacuum), and

temperature (slopes and plateaus) dependent neutron

diffraction experiments have been performed. For

example, they permit the analysis of the structural

aspects and the chemical phase transformations when

the HDDR route is applied. This process is one of the

most powerful ways to form a strongly coercive

microstructure in micrometer-sized powders as used

for bonded magnet technology (Liesert et al. 1997).

Neutron diffraction using PSD techniques is well

suited to reproduce the high-temperature thermal and

annealing treatments on real magnetic materials.

In situ experiments permit the correlation of known

dilatometric results with phase and structure trans-

formations in bulk materials. Finally, using a high

counting rate PSD, such as the D20 diffractometer at

ILL, one can extract significant crystal structure and

kinetic information in reasonable times even from

only a tiny amount of material (a few micrometers

thick), e.g., surface corrosion of material at moderate

temperature, under specific atmospheres.

2.6 Texture and Microstructure Analysis of Magnets

Cradle circle equipment can be used to analyze the

texture parameters (relative grain orientation of the

main phase). The orientation of the grains is a critical

parameter to form fully anisotropic magnets, thus

providing high levels of induction, i.e., large energy

products. Texturing of microcrystalline assemblies

can be achieved by using different routes depending

on the final state (use) of the magnet. The well-known

fully dense sintered magnets are treated at a high

temperature under high stress (see Magnets: Sinte-

red). A preferential orientation of isotropic micro-

crystalline particles can be achieved by die up-setting

and high-temperature fast forging (see Textured

Magnets: Deformation-induced).

Neutron diffraction texture analysis is a good tool

for examining the surfaces as well as the core of large

samples (sampling size of a few cubic millimeters)

after the material submitted to high stress. Different

types of magnetic material can be checked using tex-

ture analysis. Using this technique, it has been shown

for Nd–Fe–B materials, that fast forging at high

temperature is very efficient in order to align most of

the microcrystallite axes along the forging direction.

These axes are initially in-plane aligned as a result of

the book-mold procedure used during cooling the

magnet material (Rivoirard et al. 2000). Moreover,

the effectiveness of the metallurgical procedure is

correlated to a ductile-to-brittle phase transformation

and to rheological phenomena existing in the range

850–950 1C.

2.7 Laue and Reflectometry Methods

The white-beam technique of the Laue method

should be mentioned. Again, owing to the excellent

penetration ability of the neutron, the Laue method

can be efficiently used to analyze macro- and micro-

ordered materials. The first obvious use of a neutron

diffraction Laue setup is to control the quality and

the orientation of a single crystal within its full vol-

ume before other investigations (INS, PND, four-

circle, etc.). With one exposure many details of large

parts of the reciprocal space can be analyzed and ev-

idence of, for example, twins, defects, dislocations,

and strain fields can be obtained. The same method

has been used to determine the temperature, magnetic

field, and even pressure dependence of magnetic do-

mains up to the limit of resolution of the camera film,

i.e., a few micrometers (Tanner et al. 1992).

Because new materials are designed for integrated

purposes and the needs of densified media for re-

cording (e.g., using hard magnetic compounds), ma-

terials science is more and more concerned with

nanoscale samples. Neutron reflectometry is a very

interesting technique not only for providing informa-

tion on the quality of thin-layer samples (crystalline

and magnetic roughness) but also for analyzing the

interface magnetic coupling, the superstructure mag-

netic ordering reflecting the competition between

exchange forces, polarization effects via conduction

1022

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments

electrons, or large magnetocrystalline anisotropy of

interfaces. As the scattered signals are of nuclear or

magnetic origin, or both, the effectiveness of mag-

netic reflectometry takes advantage of polarized neu-

tron beams and polarization analysis techniques.

3. Conclusion

Scattering methods using thermal neutrons are par-

ticularly well suited to deliver unique information on

magnetic materials, and more particularly on those

expected to show potential as high-performance mag-

nets. Such magnetic materials are composed of tran-

sition and rare-earth metals, but often also contain

further elements in rather small amounts. The large

dimensional range (from electrons or orbitals to mi-

cro- and centimeter scales) can be treated using a very

wide range of powerful techniques. This allows not

only the characterization of static parameters, but

also of dynamics and excitation phenomena, thus ef-

fectively providing typical energies. Both aspects are

associated with the intrinsic quantities, such as mag-

netization, exchange forces, and CEF strengths.

Many extrinsic but critical quantities can also be

analyzed, especially those being relevant for chemical

procedures, processes, microstructure optimization,

etc. The multipurpose neutron scattering techniques

as such have no equivalent, especially because of their

efficiency in depth penetration, contrary to x-ray

techniques. Owing to the increasing neutron fluxes

and to the correspondingly improved detection tech-

niques, more and more detailed information can be

obtained. Hence, either microintegrated materials or

microstructured functional materials can be investi-

gated to satisfy the interest in these materials. It can

be very fruitful to combine the neutron investigation

methods as described here with more conventional,

laboratory-scale techniques to support the produc-

tion of new, hard magnetic materials.

See also: Crystal Field Effects in Intermetallic

Compounds: Inelastic Neutron Scattering Results;

Magnetic Excitations in Solids

Bibliography

Brown P J 1992 Magnetic form factors. In: Wilson A J C (ed.)

International Tables for Crystallography. Kluwer, London,

pp. 391–9

Clausen K N, Lebech B 1982 J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 15,

5095

Colpa J H P, Sinnema S, Frings P H, Franse J J, Radvanski R J

1989 J. Phys. Cond. Matter 1, 2047

Fruchart D, Isnard O, Miraglia S, Pontonnier L, Soubeyroux J

L, Fruchart R 1994 R

2

Fe

17

and RM

12

carbide and carbon-

itride synthesis from heavy hydrocarbon compounds. J.

Alloys Comp. 203, 157–63

Fruchart D, Wolfers P, Vuillet P, Yaouanc A, Fruchart R,

L’He

´

ritier P 1984 Structural and magnetic properties of

RE

2

Fe

14

B hydrides. In: Mitchell I V (ed.) Nd–Fe Permanent

Magnets: Their Present and Future Applications. CEC, Brus-

sels, Belgium, pp. 173–8

Garcia-Landa B 1994 Doctoral thesis. University of Zaragoza,

Spain

Givord D, Laforest J, Lemaire R 1977 Magnetic transition

in ThCo

5

due to change of Co-moment. Physica B 86–88B,

204–6

Givord D, Laforest J, Schweizer J, Tasset F 1979 J. Appl. Phys.

50, 2008

Givord D, Li H S, Moreau J M 1984 Solid State Commun. 50,

497

Givord D, Li H S, Tasset F 1985 Polarized neutron study of

the compounds Y

2

Fe

14

B and Nd

2

Fe

14

B. J. Appl. Phys. 57,

4100–2

Herbst J F, Croat J J, Pinkerton F E, Yelon W B 1984 Phys.

Rev. B 29, 4176

Isnard O, Miraglia S, Soubeyroux J L, Fruchart D, Stergiou A

1990 Neutron diffraction study of the structural and mag-

netic properties of the R

2

Fe

17

H

x

(D

x

) ternary compounds

(R ¼Ce, Nd and Ho). J. Less-Common Metals. 162, 273–84

Koyama K, Fujii H 2000 Nitrogen gas–solid reaction process

and basic magnetism of the interstitially modified rare-earth

3d transition-metal nitrides R

2

Fe

17

N

3

(R ¼Y, Ce, Nd, Sm)

and Y

2

Co

17

N

3

. Phys. Rev. B 61, 9475–93

Liesert S, Fruchart D, de Rango P, Soubeyroux J L 1997 The

hydrogenation–disproportionation—desorption–recombina-

tion process of Nd

2

Fe

14

B studied by in-situ neutron diffrac-

tion and thermomagnetic measurements. J. Alloys Comp.

253–254, 140–3

Loewenhaupt M, Prager M, Murani A P, Hoenig H E 1988

Inelastic neutron scattering on RE

2

Fe

14

B (RE ¼Y, Ce, Nd,

Dy and Er). J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 76–77, 408–10

Mayer H M, Steiner M, Stu

¨

sser N, Weinfurter W, Dorner B,

Lindga

˚

rd P A, Clausen K N, Hock S, Verhoef R 1992 Inelastic

neutron scattering measurements on Nd

2

Fe

14

B and Y

2

Fe

14

B

single crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 104–107, 1295–7

Mishra S R, Long G L, Pringle O A, Middleton D P, Hu Z,

Yelon W B, Grandjean F, Buschow K H J 1996 A magnetic

neutron diffraction, and Mo

¨

ssbauer spectral study of the

Ce

2

Fe

17–x

Al

x

solid solutions. J. Appl. Phys. 79, 3145–55

Rivoirard S, Fruchart D, de Rango P, de la Perrier B aˆ thie R,

Chateigner D 2000 Proc. 6th Int. Workshop on Rare-Earth

Magnets and their Applications. Sendaı

¨

, Japan

Scha

¨

fer W, Kockelmann W, Will G, Fischer P, Gal J 1994

Atomic distribution in RFe

x

Al

12x

compounds with R ¼Tb,

Dy, Ho, Er, Tm and Fe concentrations x l 5 studied by

neutron diffraction. J. Alloys Comp. 207, 316–20

Schweizer J, Tasset F 1980 J. Phys. F: Metal Phys. 10, 2799

Sears, V F 1984 AECL report 8490. Atomic Energy of Canada

Shoemaker D P, Shoemaker C B, Fruchart R 1984 The struc-

ture of a new magnetic phase related to the sigma phase: iron

neodymium boride Nd

2

Fe

14

B. Acta Crystallogr. C40, 1665–8

Tanner B K, Baruchel J, Abell J S 1992 Internal magnetic do-

main structure changes in thick TbAl

2

crystals revealed by

polarized neutron topography. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 104,

317–8

Wolfers P, Obbade S, Fruchart D, Verhoef R 1996 Precise

crystal and magnetic structure determinations: I. A neutron

diffraction study of Nd

2

Fe

14

Bat20K.J. Alloys Comp. 242,

74–9

D. Fruchart

Laboratoire de Cristallographie du CNRS, Grenoble

France

1023

Permanent Magnet Materials: Neutron Experiments

Permanent Magnetic Devices in Otiatria

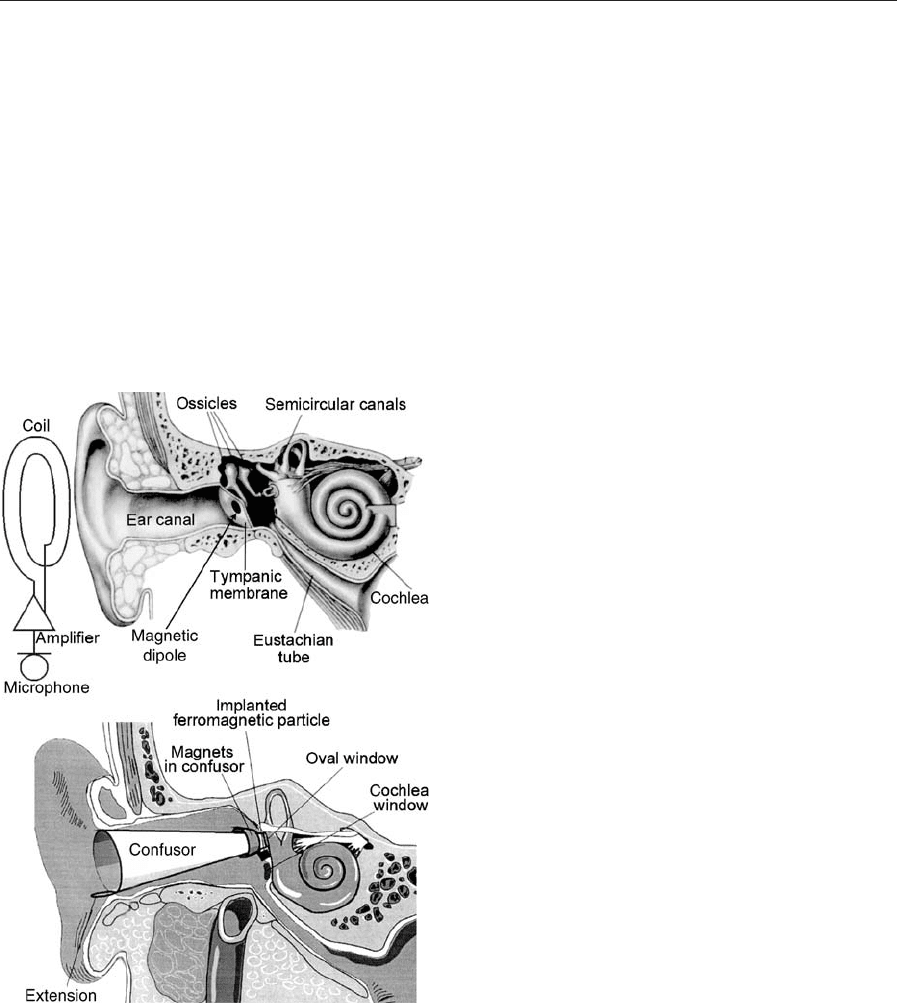

Inflammatory diseases of middle ear often result in

partial or complete destruction of its sound conduct-

ing elements: perforation of tympanic membrane,

damage to or destruction of ossicles (hammer, anvil,

stirrup) (Fig. 1; Kobrak et al. 1963, Wullstein et al.

1972, Williams and Rouf 1978, Ferris et al. 1998,

Kuvnetsov et al. 2001). This typically leads to signi-

ficant deterioration or complete loss of hearing.

Prosthesing of such miniature elements in a narrow

passage, while preserving the physiological level of

signal transduction and protecting the inner ear from

overloading, is a challenging task for the surgeon and

imposes rigorous requirements on materials for such

prostheses. Application of modern magnetic materi-

als such as SmCo

5

and NdFeB (see Rare Earth Mag-

nets: Materials and Magnets: Sintered) makes it

possible to manufacture miniature magnets with high

magnetic energy. These magnets can produce me-

chanical forces, typical for middle ear, even in mag-

netic systems with open magnetic circuits. A human

ear can hear sounds with intensities of up to 120 dB

(L ¼20 log(P/P

0

), where P

0

¼2 10

5

Nm

2

is the

audibility threshold, L is the sound intensity level).

So, the maximum sound pressure P on the tympanic

membrane can be estimated to be 20 N m

2

, and,

therefore, maximum forces in the middle ear do not

exceed 0.001–0.1 N. Such forces can be achieved by

permanent magnets with masses 0.01–10 g, which are

close to that of ossicles (several grams). These small

magnets can be produced in practically any size and

shape, be covered with biologically inert materials

and their magnetization can be precisely controlled.

Elastic magnets can also be manufactured (see

Magnets: Bonded Permanent Magnets). Thus, a vari-

ety of functional prostheses of middle ear elements

based on such miniature magnets can be created.

1. Tympanic Membrane Prosthesing

Tympanic membrane prosthesing in outpatients with

dry perforative otitis media can be achieved using

two thin sheets of a magnetic elastomer (rare-earth

alloy particles, embedded in a biocompatible plastic,

e.g., silicone). The prosthesing procedure includes in-

sertion of one compactly rolled sheet of the magnetic

elastomer through the tympanic membrane perfora-

tion into the inner ear cavity, where it is unfolded

using a special tool (S) (Dmitriev and Yunin 1988). A

second magnetic sheet is applied from the outer side

of the tympanic membrane. The two sheets attract

each other, sealing the perforation. This procedure

has lead to 15–25 dB improvement in hearing of 27

patients with two-sided dry perforative otitis media

and regeneration of tympanic membranes in two

patients.

2. Magnetic Prostheses of Ossicles

All known types of the ossicular implants form joint-

less junctions, which dramatically changes the middle

ear acoustic impedance. Permanent magnet-based

selforganizing prosthetic devices can preserve the

physiological mechanism of sound conduction in the

middle ear and simplify surgeons’ work. For exam-

ple, an anvil prosthesis consists of a horseshoe-

shaped ferromagnetic element inserted under the

stirrup arch and a magnet-containing stem, attached

either to the hammer or to the tympanic or artificial

membrane (Kuznetsov et al. 1983a, 1983b, 2001). The

two parts attach to each other by magnetic forces,

forming a slip-free magnetic junction between them,

Figure 1

Main elements of a human ear and one of the schemes of

hearing rehabilitation using an implanted miniature

permanent magnet (top). The magnet is vibrated by an

external alternating magnetic field of sound frequency

and generates acoustic perceptions for the patient.

Application of a removable confusor in patients with

total absence of the middle ear sound conducting system

(bottom).

1024

Permanent Magnetic Devices in Otiatr ia

while the anvil-stirrup joint remains physiologically

flexible. Nonmagnetic elements of the prostheses are

made of rigid and light weight carbon fiber-based

materials. Flexibility of the construction prevents

overloading of the inner ear. Hearing improvement

(20–40 dB of sound conductivity) was observed in 25

of 30 patients with chronic suppurative otitis media,

who were implanted with anvil prostheses, and in 24

of 30 patients with stirrup prostheses (up to 35 dB).

Prostheses of ossicles with magnetic elements also al-

low to vibromassage the middle ear system by an ex-

ternal alternating magnetic field, preventing

immobilization of the prosthesis due to conjunctive

tissue formation.

3. Prosthesing of the Middle Ear Sound

Conducting System after a Radical Surgery

In patients with completely destroyed middle ear

sound conducting system, but an intact inner ear,

hearing rehabilitation requires both adjustment of the

prosthesis impedance with the impedance of the inner

ear and shielding of the round window. Magnetically

soft ferromagnetic particles (steel X13) were implant-

ed under the cicatrical tissue of oval window area in

postoperative patients with chronic suppurative otitis

media, impermeable auditory tube and total absence

of the sound conducting system (Kuznetsov et al.

1982, Palchun et al. 1982). A removable elastic con-

fusor, containing small permanent magnets, was at-

tached to the cochlea window by magnetic forces

(Fig. 1). This confusor focuses sound pressure on the

oval window while shielding the round window. Since

magnetic forces guide the confusor to the proper

position during insertion into the ear canal, this

procedure can be done by the patient. Confusor

prosthesing provided up to 35 dB decrease in air con-

duction thresholds in 18 patients, which is approxi-

mately two times better, than traditional techniques

such as shielding of the round window by oiled cot-

ton tampons or by silicone-based foam ‘‘otopen’’

(Wullstein et al. 1972, Williams and Rouf 1978).

4. Excitation of Acoustic Vibrations in the Middle

Ear Using Sound Frequency Alternating Magnetic

Field Action on a Magnetic Element in the Sound

Conducting System

Implantation of miniature permanent magnets into

nonmagnetic biological structures of middle ear

makes it possible to transform sound frequency al-

ternating magnetic fields into mechanical stimuli,

which can be perceived by the patient as acoustic

signals (Fig. 1; Kuzhetsov et al. 1983a, 1983b, 2001,

Dmitriev et al. 1986, 1988).

Many coils can generate suitable alternating mag-

netic fields, but a flat, spiral coil, concealed under

clothes on the patient’s shoulder appears to be the

most promising. It can generate a sound frequency

alternating magnetic field from 10

2

Oe to 10 Oe in

the ear cavity, providing adequate mechanical stim-

uli. Due to a relatively large distance from the coil to

the ear, the field in the ear cavity is practically uni-

form: rBE10

6

Oe cm

1

. The force F acting on the

magnetic moment m is proportional to rB:

F ¼(m r)B, while the torque M acting on the same

magnetic moment is proportional to H: M ¼m H.

Therefore, in such field a magnetic dipole will oscil-

late mostly tangentially. Elements of the middle ear

sound conducting system (ossicles, stirrup base) nor-

mally also move predominantly tangentially. Thus,

the movements of the magnet can simulate move-

ments of the ossicles in a normal ear and provide

acoustic stimuli for the patient.

Depending on the degree of the middle ear dete-

rioration, the location of the magnet varies: it can be

either glued to the remaining tympanic membrane, or

attached to ossicles (or be a part of an ossicle pros-

thesis), or implanted into the cicatrical tissue on the

oval window surface after a radical operation. The

latter was the most common technique and was used

in 11 patients. Biocompatible 5–50 mg SmCo

5

mono-

crystals were used. To increase the coercive force and

retentivity, the monocrystals were treated by a shock

wave before magnetization (Kuznetsov et al. 1977).

Significant rehabilitation efficiency in patients with

hearing thresholds of up to 70 dB was observed after

such operations. The patients were monitored for

several years and no negative effects of the magnets

or magnetic fields on the tissues and the processes in

the ear were detected.

Attaching a magnet to the tympanic membrane in

patients with an intact middle ear, but a reduced

sensitivity of the inner ear, and vibrating it with an

external alternating magnetic field can provide addi-

tional mechanical stimulation. Extensive experimen-

tal studies were done on cadaver material to optimize

the magnet size to provide a natural level of sound

pressure on the tympanic membrane. Optimal mag-

net size was found to be 56 mg (Dmitriev and

Aknesov 1992). This technique provides a significant

improvement of sound perception for all tested mag-

net locations and solves cosmetic problems of hearing

rehabilitation (no wires, earpiece).

5. Magnetically Controlled Implantable Devices

for Restoration of Inner Ear Function in Me

´

nie

`

re’s

Disease Patients

Me

´

nie

`

re’s disease (labyrinth hydrops) is a serious in-

ner ear disease, characterized by an increase of the

hydrostatic pressure of intralabyrinth fluids, leading

to irreversible destruction of hearing and vestibular

functions. This ailment is treated by draining the

excess endolymph from the labyrinth to normalize

1025

Permanent Magnetic Devices in Otiatria

the pressure using several types of implantable drain-

age devices, thus eliminating vertigo and preserving

the remaining hearing level (Kobrak 1963).

Unfortunately, opening thresholds of these devices

cannot be adjusted after implantation and the pres-

sure in the labyrinth cannot be maintained at the

level, optimum for the particular patient. Two types

of implantable magnetic valves for draining endo-

lymphatic sack were developed and tested (Kuznet-

sov et al. 1985, Yunin et al. 1984). Core elements of

the valves are rare-earth permanent magnets and

magnetic elastomers. Different compositions of mag-

netic particles (barium hexaferrite and/or rare-earth

alloys) imbedded in silicone enable to create el-

astomers with a wide variety of magnetic properties.

Magnetic elastomers were attracted to each other or

permanent magnets and closed the endolymph out-

flow. The devices were grafted into the inner ear of

the patients. During an attack, a postoperative pa-

tient can open the type I valve and decrease the

endolymph pressure by bringing a magnet close to

the implanted valve. Once the magnet is removed, the

valve closes. Type II valves open automatically when

the endolymph pressure exceeds a certain threshold.

The valve opening threshold can be adjusted after

grafting of the device by changing magnetization of

the elastomer using an external impulse magnetiza-

tion device. Thus, a physician can optimize the endo-

lymph pressure for each particular patient and adjust

it to a comfortable level in response to the patient’s

condition without surgery. Elastomers in the valves

can be vibrated by external alternative magnetic field,

preventing clogging of the valve due to conjunctive

tissue formation and allowing active pumping of

endolymph if necessary.

Six patients were implanted with type I valves, and

another five received type II valves. The patients were

monitored for more than seven years and demon-

strated stable improvement in their condition: vertigo

attacks were controlled by the valves, hearing levels

were maintained. The patients were able to work and

live normal lives.

6. Concluding Remarks

A variety of implantable prostheses of middle ear

structures based on permanent magnets and using

magneto-mechanical forces for their operation were

developed for treating middle ear ailments and hear-

ing rehabilitation. Methods of surgical application

of the devices were developed and in clinical trials

more than 85% of 127 patients with different degrees

of middle ear system degradation have shown stable

improvement. This promising technology increases

reliability of functional results, but needs further de-

velopment and approval of regulatory authorities

(FDA, etc.) for wider clinical trials and use.

Bibliography

Dmitriev N S, Aknesov Yu A 1992 Principle measurement

scheme of transductional properties of permanent magnets.

Current Problems of Clinical Otolaryngology. Irkutsk, Russia,

p. 355

Dmitriev N S, Yunin A M 1988 USSR Patent 1421332

Dmitriev N S, Yunin A M, Kuznetsov A A 1986 USSR Patent

1237170

Ferris P, Prendergast P J, Rice H J, Blayney A W 1998 Finite

element modeling of prostheses for ossicular chain recon-

struction. J. Biomech. 31, 130

Kobrak H G 1963 Middle Ear. Medicina, Moscow

Kuznetsov A A, Nikiforov A K, Adadurov G A, Mishin D D

1977 Magnetic Properties of SmCo

5

monocrystals Subjected

to Shock waves. Izvestia Visshih Uchebnyh Zavedenii (Phys-

ics) 5, 137–9

Kuznetsov A A, Dmitriev N S, Palchun V T, Yunin A M 1982

USSR Patent 950374

Kuznetsov A A, Dmitriev N S, Yunin A M 1983a USSR Patent

1076114

Kuznetsov A A, Dmitriev N S, Yunin A M, Kazakova Z I

1983b USSR Patent 1041110

Kuznetsov A A, Yunin A M, Palchun V T, Dmitriev N S 1985

USSR Patent 1159572

Kuznetsov A A, Yunin A M, Dmitriev N S, Palchun V T 2001

Applications of Magnetic devices in otiatria. JMMM 225,

202–8

Palchun V T, Dmitriev N S, Kuznetsov A A, Yunin A M 1982

USSR Patent 971287

Williams D F, Rouf R 1978 Implants in surgery. Medicina,

Moscow

Wullstein H L 1972 Hearing Improvement Operations. Med-

icina, Moscow

Yunin A M, Kuznetsov A A, Palchun V T, Dmitriev N S 1984

USSR Patent 1151141

A. A. Kuznetsov, N. S. Dmitriev, M. Yunin,

A. Savichev and O. A. Kuznetsov

University of Missouri at Columbia, USA

Permanent Magnets: Corrosion Properties

The rare-earth permanent magnets, particularly Nd–

Fe–B magnets, possess outstanding magnetic prop-

erties and therefore have grown rapidly in production

(see Rare Earth Magnets: Materials; Magnets: Sinte-

red). However, their poor corrosion resistance

(Jacobson and Kim 1987) has limited their applica-

tions. This article discusses the corrosion mechanism

of Nd–Fe–B magnets and methods to improve their

corrosion resistance.

1. Corrosion Mechanism

Permanent magnets based on Nd–Fe–B are very sen-

sitive to various corrosive environments. The great

sensitivity to corrosion is caused by the considerable

amount of rare-earth element in their composition,

1026

Permanent Magnets: Corrosion Properties

since the electromotive forces of rare-earth elements

are much larger than those of iron. Normally, Nd–

Fe–B magnets consist of three phases: (i) the main

Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase; (ii) a neodymium-rich (usually

Nd

4

Fe) phase, and (iii) a boron-rich phase. From

the electrical point of view, such a contact of three

different metallic phases with great differences in

electrochemical activity must promote rapid corro-

sion. Nakamura et al. (1989) measured the electrode

potentials of the different phases in 1 N HCl solution.

Because the Nd-rich phase has a much lower elec-

trode potential than the Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase, a selective

corrosion of the Nd-rich phase occurs by forming a

local cell between the Nd

2

Fe

14

B and Nd-rich phases.

Therefore, the grain boundary phase corrosion is

dominant rather than uniform corrosion for sintered

Nd–Fe–B magnets, a fact made evident by micro-

structural observation. The corrosion rate decreases

as the Nd content (or volume fraction of Nd-rich

phase) decreases. On the other hand, with the increase

of cathodic polarization in strong acid, the hydrogen

reduction reaction produces hydrogen atoms at the

cathode that can diffuse into the base metal and cause

embrittlement, and therefore the rate of Nd–Fe–B

magnet dissolution increases (Bala and Szymura

1991). The abnormal dissolution (mechanical degra-

dation) rate increases linearly with the square root of

the hydrogen evolution current density.

Since the Nd–Fe–B magnets are generally used in

atmospheric environments, various accelerated cor-

rosion environment tests were employed in order to

predict the service life of the magnet in ambient en-

vironments. The accelerated corrosion environments

include: hot–dry air, hot–humidity, high-pressure

steam, and salted spray.

The kinetics of oxidation of Nd–Fe–B alloy mag-

nets in air at elevated temperatures (80–200 1C) ex-

hibit an exponential weight gain (Turek et al. 1994,

LeBreton and Teillet 1990). Quick initial oxidation

of the intergranular Nd-rich phases is followed by

oxidation of the Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase. The oxidation

products are Nd

2

O

3

, NdFeO

3

,Fe

3

O

4

, and an inho-

mogeneous phase close to a-Fe.

When Nd–Fe–B magnets are exposed to a hot–

humid environment (50–90 1C, 50–90% relative hu-

midity) (LeBreton and Teillet 1990), the magnet is

disintegrated but the Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase is generally

unaffected. The oxidation occurs in the Nd-rich re-

gion, producing Nd

2

O

3

and Nd(OH)

3

as is evidenced

by x-ray diffraction. This disintegration increases as

temperature and relative humidity increase.

A more accelerated corrosion test is carried out in a

high-pressure steam vessel (McGuiness et al. 1994,

Kim et al. 1996). In an autoclave (or PCT) test, grains

of the Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase have fallen apart from the

magnet. X-ray diffraction patterns on the loose par-

ticles exhibit mainly Nd

2

Fe

14

B peaks with small

Nd(OH)

3

peaks indicating that the oxidation product

is Nd(OH)

3

and the Nd

2

Fe

14

B remains unspoiled.

Macroscopic disintegration was observed on both

magnetic pole faces of the magnetically aligned and

sintered Nd–Fe–B magnet after exposure to an auto-

clave environment at 115 1C and 2 bar, which is sim-

ilar to the conditions of hydrogen decrepitation of the

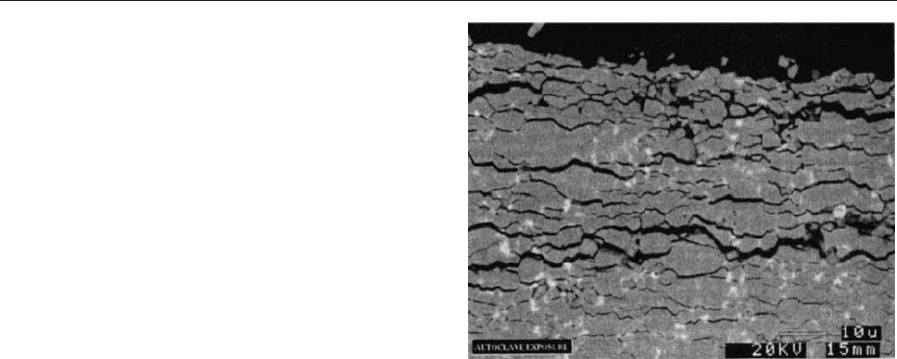

magnet. The microstructure underneath the disinte-

gration surface shows plate-like cracking perpendic-

ular to the magnetic orientation as shown in Fig. 1.

The microstructure of hydrogen-decrepitated sam-

ples shows similar cracking patterns. There is un-

doubtedly anisotropic corrosion and hydrogen

decrepitation behavior in anisotropic Nd–Fe–B mag-

nets. The similarity between these two corrosion

processes infers a common corrosion mechanism. As

described before, the hydrogen evolution during ca-

thodic polarization of Nd–Fe–B in strong acid causes

mechanical degradation (abnormal dissolution), and

thus hydrogen decrepitation is involved and plays an

important role in the corrosion mechanism. Hydro-

gen may be generated in the autoclave test from the

decomposition of water vapor:

3H

2

O þ Nd-NdðOHÞ

3

þ 3H

Thus, the corrosion mechanism for Nd–Fe–B mag-

nets in the heat and humidity of the autoclave test

starts with a surface reaction of water vapor with the

Nd-rich grain boundary phase. The generated hy-

drogen atoms diffuse along the grain boundaries into

the interior of the magnet. Some of the hydrogen re-

acts with the Nd-rich grain boundary phase, causing

volume expansion of this phase (3H þNd -NdH

3

)

and the rest goes into the Nd

2

Fe

14

B matrix (xH þ

Nd

2

Fe

14

B-Nd

2

Fe

14

BH

x

). The corrosion product of

Nd

2

Fe

14

B characterized by x-ray diffraction reveals

that a significant expansion of the lattice has taken

Figure 1

SEM micrograph of a Nd–Fe–B magnet subjected to an

autoclave test (Kim et al. 1996).

1027

Permanent Magnets: Corrosion Properties

place (McGuiness et al. 1994). Volume expansion of

the Nd-rich phase and lattice expansion of the

Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase results in the removal of the

Nd

2

Fe

14

B matrix phase grains. The subsurface cracks

provide the path for reacting species (water vapor) to

the inside of the Nd-rich phase, which accelerates the

corrosion reaction. This corrosion reaction increases

as the amount of Nd-rich phase in the Nd–Fe–B

magnet increases.

2. Improvement of Corrosion Resistance

As discussed in Sect. 1, the large difference in the

electrochemical potential between the Nd-rich and

Nd

2

Fe

14

B phases promotes a rapid corrosion reac-

tion. The grain boundary also provides the diffusion

path of reacting species such as hydrogen atoms. Im-

provement of corrosion resistance can therefore be

achieved by increasing the electrode potential of

the Nd-rich phase as close as possible to that of the

Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase and by minimizing the Nd-rich

region.

Partial substitution of iron by cobalt is reported

substantially to improve the corrosion resistance by

forming the Nd

3

Co phase in the Nd-rich grain

boundary, particularly in a hot–humid environment

(Tokunara and Hirosawa 1991, Kim and Camp

1996). The electrode potential of Nd

3

Co is higher

than that of the Nd

4

Fe phase and is close to the

Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase (Nakamura et al. 1989). The corro-

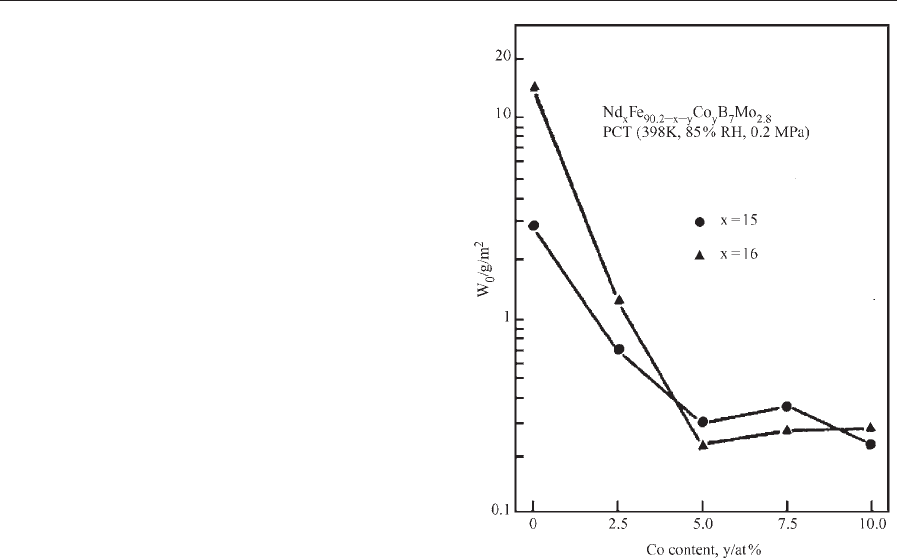

sion rate of Nd–Dy–Fe–Co–B–Mo sintered magnets,

as monitored by weight loss in PCT, is shown in

Fig. 2. This corrosion rate decreases as the cobalt

content increases to 5 at.% Co.

It is noted that a cobalt addition by itself deteri-

orates the coercivity although it improves the corro-

sion resistance and Curie temperature. Therefore,

various additional elements combined with cobalt

were investigated in order to compensate for the neg-

ative effect of reducing coercivity by cobalt. Elements

including Al, Ga, Cu, Sn, Cr, Zr, Nb, V, Mo, or W

combined with Co are found to increase the co-

ercivity. Because of these additions, the corrosion re-

sistance is further improved. Particularly, a combined

addition of cobalt and copper substantially improves

both the corrosion resistance and the coercivity with-

out reduction of the energy product (Kim and Camp

1996).

Nickel or Ni and Co additions are also reported to

improve significantly the corrosion resistance (Bala

et al. 1990). The segregation of nickel to the inter-

granular Nd-rich phase would reduce the electro-

chemical difference among the phases yielding good

corrosion resistance. It is noted, however, that a

nickel addition deteriorates coercivity and reduces

the Curie temperature. A further small addition of

titanium in a Nd–(Fe,Co,Ni)–B alloy enhances the

coercivity to a moderate level. Vanadium or molyb-

denum additions were also reported to improve co-

ercivity and corrosion resistance by forming

intergranular precipitates (Fe–M

2

-B

2

), but at the

expense of the energy product (Hirosawa et al. 1990).

A partial replacement of Nd by dysprosium or

terbium in Nd–Fe–B magnets also improves the cor-

rosion resistance. The lowering of the total rare-earth

amount in Nd–Fe–B magnets increases the volume

fraction of the Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase and thus raises the

electrode potential, which improves the corrosion re-

sistance (Tokunara and Hirosawa 1991). Chromate

etching on the surface of the magnet dissolves the

Nd-rich surface phase. This eliminates the reaction

site, which also improves the corrosion resistance

(Kim 1989).

In addition, increasing density and minimizing po-

rosity also improves the corrosion resistance. The

corrosion current reportedly increases as the porosity

increases in the magnet. A vacuum impregnation of

the surface porosity was reported to improve the

corrosion resistance (Stevenson and Stevenson 1988).

The microstructure of Nd–Fe–B magnets also affects

their corrosion behavior. Nanostructured melt-spun

ribbons exhibit a uniform corrosion, while the sinte-

red magnets exhibit a localized corrosion of the

Figure 2

Weight loss per unit area of uncoated magnets in PCT

for 130 ks as a function of cobalt content (Tokunara and

Hirosawa 1991).

1028

Permanent Magnets: Corrosion Properties

Nd-rich grain boundary phase (Nakamura et al.

1989). The latter has a lower electrode potential

and thus a poorer corrosion resistance. Hot-worked

Nd–Fe–B magnets also exhibit better corrosion resis-

tance than the sintered magnets (Nozieres and Taylor

1990).

A postmachining heat treatment of Nd–Fe–B sin-

tered magnets at 600–1000 1C in a vacuum or in a

very low oxygen environment formed a very thin

oxidation layer on the surface and thus improved the

corrosion resistance in hot–humid environments

(Imaizumi et al. 1987).

3. Corrosion Protection

The corrosion resistance is further improved by ap-

plying corrosion protection layers on the surface of

the magnet (Mitchell 1990). Various depositing ma-

terials can be put on the magnet surface by using

various techniques. Plating can be described as the

deposition of a material from a solution. There are

two main types of plating: one is electrolytic or elect-

roless plating and the second is electropainting. The

most common coating is electrolytic or electroless

plating of Ni, Sn, Cu, or combinations of these, be-

cause of ease of mass production, economic process,

and durability.

However, an adjusted pretreatment to inhibit a re-

action of nickel with the magnet is needed because

Nd–Fe–B magnets may absorb hydrogen during the

plating process causing cracking and, thus, failure of

adherence of the layer to the magnet. Nickel plating

usually exhibits a good corrosion resistance in hot–

humid environments but a poor resistance in salt-

spray environments. The cathodically deposited elect-

ropaint coating is also very popular because of its

ease for mass production. The electropaint coating

usually exhibits an excellent corrosion resistance in

salt-spray environments and a moderate resistance in

hot–humid environments.

Vapor deposition generally refers to the deposition

of a material on to a substrate by use of the gaseous

phase of the depositing material. There are several

forms of vapor deposition as physical, chemical, and

spray deposition. Among them the aluminum-ion

vapor deposit coating is important for achieving a

high corrosion resistance. It provides the highest de-

gree of protection against hot–humid environments

and exhibits a moderately good resistance to salt-spray.

See also: Magnets: High-temperature; Magnets:

Remanence-enhanced

Bibliography

Bala H, Szymura S 1991 An electrochemical investigation

of dissolution of Nd–Fe–B magnets in acid-solution under

cathodic polarization. Corros. Sci. 32, 953–63

Bala H, Szymura S, Wyslocki J J 1990 Corrosion characteristics

of Nd

2

Fe

14x

Ni

x

B permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn.

26, 2646–8

Hirosawa S, Tomizawa H, Mino S, Hamamura A 1990 High-

coercivity Nd–Fe–B-type permanent magnets with less dys-

prosium. IEEE Trans. Magn. 26, 1960–2

Imaizumi N, Inoue N, Takahashi K 1987 Effects of post-

matching heat treatment on the magnetic properties and the

corrosion of NdFeB magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 23, 3610–2

Jacobson J, Kim A 1987 Oxidation behavior of Nd–Fe–B mag-

nets. J. Appl. Phys. 61, 3763–5

Kim A S 1989 J. Mater. Eng. 11,95

Kim A S, Camp F E 1996 High performance NdFeB magnets.

J. Appl. Phys. 79, 5035–9

Kim A S, Camp F E, Lizzi T 1996 Hydrogen induced corrosion

mechanism in NdFeB magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 79, 4840–2

LeBreton J M, Teillet J 1990 Oxidation of (Nd,Dy)FeB per-

manent magnets investigated by

57

Fe Mossbauer spectro-

scopy. IEEE Trans. Magn. 26, 2652–4

McGuiness P J, Fitzpatrick L, Yartys V A, Harris I R 1994

Anisotropic hydrogen decrepitation and corrosion behavior

in NdFeB magnets. J. Alloy Comp. 206, L7–10

Mitchell P 1990 Corrosion protection of NdFeB magnets. IEEE

Trans. Magn. 26, 1933–5

Nakamura H, Fukuno A, Yoneyama T 1989 In: Proc. 10th Int.

Workshop on Rare Earth Magnets and their Applications.

Kyoto, Japan, p. 315

Nozieres J P, Taylor D W 1990 Corrosion resistance of hot-

worked NdFeB permanent magnets. J. Less-Com. Metals.

162, L1–5

Stevenson M, Stevenson J Jr 1988 Metal Finishing 86,93

Tokunara K, Hirosawa S 1991 J. Appl. Phys. 79, 5521

Turek K, Liszkowski P, Figiel 1994 The kinetics of oxidation of

Nd–Fe–B powders. IEEE Trans. Magn. 29, 2782–4

A. S. Kim

JAHWA Electronics Co., Ltd., Choong-Book

Korea

Permanent Magnets: Microstructure

The microstructure of rare earth permanent magnet

materials is defined by the type, the structure and the

number of phases, by the size, shape and the topo-

logical arrangement of the individual phase regions

and their interfaces, and by the type, structure and

geometry of lattice defects. In the following, several

examples of TEM micrographs will show the differ-

ences between various types of rare earth magnets

(see Rare Earth Magnets: Materials). The importance

of newly developed permanent magnetic materials

in many electro-, magnetomechanical and electronic

applications can be attributed to the drastic improve-

ment of microstructure related properties, such as

the magnetic energy density product and the coercive

field.

The rare earth intermetallic phases with a high

uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy (see Magnetic

1029

Permanent Magnets: Micro structure