Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

negligible effect on the matrix. However, there are

some disadvantages.

If interactions become too strong, the oscillations

in R(t) become too fast to detect. Therefore, there is

an upper limit to the interaction strength detectable

by PAC. If the interaction is too weak, a single os-

cillation takes longer than the time interval where

enough data can be gathered. This determines the

lower limit of the detectable interaction strengths. In

MS only such a lower limit is present. Another ad-

vantage of MS is that it can measure the s electron

density in the nucleus by the isomer shift, a quantity

not probed by PAC. Finally, PAC is suited for some

nuclei which are inaccessible by MS and vice versa

(the most common PAC nuclei are

111

Cd (parent

111

In),

181

Ta (parent

181

Hf), and

100

Pd (parent

100

Rh)). The above aspects of PAC and MS indicate

that the two methods are complementary.

4. Information Obtained in a PAC Experiment

4.1 Site Occupation

The R(t) function is characteristic for a specific en-

vironment felt by the probe nucleus. If two or more

distinct environments are present, the measured R(t)

is a sum of the R(t) functions due to each environ-

ment. The distinct sites can, for example, be non-

equivalent lattice positions, a substitutional and an

interstitial position, or a surface and a bulk position.

Unraveling a measured R (t) function into the partial

R(t) functions from which it is built, and assigning

these to a specific position in the sample makes it

possible to track their occupation by probe atoms.

This enables, for example, a study of the formation

and migration of defect complexes as a function of

temperature.

4.2 Magnitude of the Magnetic Hyperfine Field

The frequencies of an R(t) function are proportional

to the Larmor precession frequency, and hence to the

strength of the magnetic hyperfine field. Quantitative

information on the hyperfine field is useful for, e.g.,

position assignment (see Sect. 4.1). Also, it can help

to determine the type of magnetic order, or at least to

exclude some possibilities. For example, a probe nu-

cleus symmetrically surrounded by neighbors with

antiferromagnetically coupled magnetic moments will

probably feel a zero or tiny hyperfine field, whereas

this field should be considerably higher if all neigh-

bors have their magnetic moments coupled ferro-

magnetically. Since the hyperfine field is very sensitive

to electronic structure, PAC experiments also provide

the possibility of testing ab initio electronic theories.

4.3 Orientation of the Magnetic Hyperfine Field

The general formalism of PAC shows that a probe

nucleus with nuclear spin I ¼5/2 (

111

Cd) at a unique

position and feeling a single magnetic hyperfine field

generates two frequencies in R(t), i.e., n and 2n. Their

amplitude in a Fourier analysis of R(t) is related to

the absolute direction of the hyperfine field with re-

spect to the detector setup. If the hyperfine field is

perpendicular to the detector plane, only 2n is

present. If B

hf

makes an angle of 301 with the detec-

tor plane and of 451 with the first g-ray detector, then

the ratio n/2n is 3/1.

4.4 Distributions

The measured R(t) function usually shows an ampli-

tude vanishing for t4500 ns. The reason is that the

hyperfine field—and hence the frequencies making up

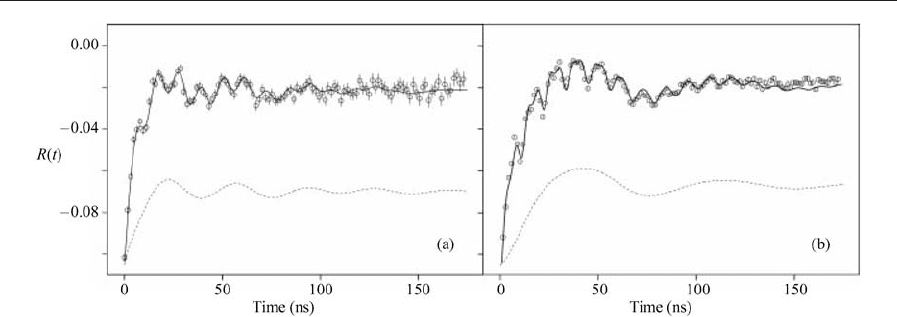

Figure 1

PAC measurements at 289 K for two different orientations (with respect to the detectors) of a Fe/Cr multilayer with

an iron thickness of 2 nm and a chromium thickness of 7.5 nm.

1050

Perturbed Angular Correlation s (PAC)

R(t)—is not an infinitely sharply determined quanti-

ty. Small intrinsic effects, such as vibrational motion

of the probe atom, can cause slight changes in the

environments, which will show up as a damping of

R(t) described by mainly Lorentzian or Gaussian

distributions on the frequencies in its Fourier spec-

trum. For such intrinsic effects, the damping is gen-

erally very weak. If, however, severe perturbations

of the environments are present, e.g., lattice defects,

vacancies, impurities, R(t) will die out much faster.

Determining the amount of distribution can therefore

tell how pure the environment of the probe is on

the atomic scale. Another use of the distribution is

discussed in Sect. 6.

5. Theoretical Understanding of Hyperfine Fields

A very important problem when using any nuclear

technique is to relate a measured hyperfine field

(which is a very local quantity) to particular chemical

and physical properties of the neighborhood of the

probe nucleus, and even of the material as a whole.

This problem was for long dealt with in a rather

crude, phenomenological way. It took until the early

1990s to be solved, when ab initio methods with

quantitative predicting power were developed. Major

work was carried out by Blaha et al. (1999) within

the framework of density functional theory (DFT,

see Density Functional Theory: Magnetism). By using

the full potential felt by the electrons and solving

the resulting Kohn–Sham equation by the linearized

augmented plane wave (LAPW) method, the tails of

the electron wave functions near the nucleus can be

calculated with a sufficient accuracy to obtain the

hyperfine field. The method has been implemented

in the computer code WIEN, which is a standard

tool for calculating hyperfine fields in a variety of

materials.

6. Example

To illustrate PAC measurements, thin Fe/Cr multi-

layers are discussed as a case study (Meersschaut

et al. 1995).

Bulk b.c.c. chromium is known to have an exotic

type of antiferromagnetic order: a spin density wave

(SDW). The moments are oriented along the 100 di-

rection and moments at neighboring atoms are an-

tiparallel. But instead of displaying the same

magnitude of moment everywhere in the crystal, as

is usual in an antiferromagnet, in chromium the mo-

ment magnitude is sinusoidally modulated with a pe-

riod of approximately 20 lattice units. Between 311K

and 123K the moments are perpendicular to the

propagation direction of the wave (transverse SDW).

Below 123K the moments are parallel to the prop-

agation direction (longitudinal SDW).

An interesting question as to the magnetic order

and the character of the SDW arises when thin chro-

mium layers are considered with a thickness ap-

proaching the period of the SDW. Will the SDW

survive or not? If so, will it be transverse or longi-

tudinal? Will the chromium moments keep their orig-

inal 100 direction? To examine this,

111

In nuclei were

implanted into a multilayer containing several Fe/Cr

bilayers, grown with the 100 direction perpendicular

to the layer. The

111

In probe atom is known to take

substitutional lattice sites in both the chromium and

iron layers, where they decay with a lifetime of 2.81

days into the PAC nucleus

111

Cd. The latter nucleus

interacts with a hyperfine field generated by the sur-

rounding cadmium electrons, which is directed along

the cadmium moment (the moment of the diamag-

netic cadmium atom is induced by, and hence is par-

allel to, the surrounding chromium moments).

The R(t) function of two PAC measurements is

shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1(a) the multilayer is parallel

to the detector plane and in Fig. 1(b) it is perpendic-

ular to it. In both R(t) functions contributions from a

slow and a fast frequency are visible. The slow fre-

quency belongs to

111

Cd nuclei in a chromium envi-

ronment and the fast one to an iron environment.

The line through the data points is a best fit, with the

chromium contribution to it shown in the lower

curves. From the change in frequencies when the

multilayer is tilted from Figs. 1(a) to (b), it can be

deduced that the hyperfine field on cadmium in chro-

mium—and therefore the chromium magnetization—

is oriented perpendicular to the plane of the multi-

layer, and hence along the 100 direction. Moreover,

the R(t) function belonging to chromium positions is

not a pure sine wave but a Bessel function. Theory

shows that this typical shape appears when the nuclei

each experience a different hyperfine field corre-

sponding to an Overhauser distribution in frequency

space and a sine wave in real space: solid proof that

the SDW is present in this type of Fe/Cr multilayer.

Furthermore it has been shown—first by PAC and

later by neutron scattering and transport methods—

that the SDW is longitudinal and disappears below a

critical chromium thickness.

See also:Mo

¨

ssbauer Spectrometry; Nuclear Mag-

netic Resonance Spectrometry

Bibliography

Blaha P, Schwarz K, Luitz J 1999 WIEN97, A Full Potential

Linearized Augmented Plane Wave Package for Calculating

Crystal Properties. Karlheinz Schwarz, Vienna (updated ver-

sion of Blaha P, Schwarz K, Sorantin P, Trickey S B Comp.

Phys. Commun. 59, 399–415)

Cahn R W, Lifshin E 1993 Concise Encyclopedia of Materials

Characterization. Pergamon, Oxford, UK

Catchen G L 1995 PAC: renaissance of a nuclear technique.

MRS Bull. (July), 37–46

1051

Perturbed Angular Correlations (PAC)

Meersschaut J, Dekoster J, Schad R, Belie

¨

n P, Rots M 1995

Spin density wave instability for chromium in Fe/Cr(100)

multilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1638–41

Schatz G, Weidinger A 1996 Nuclear Condensed Matter Phys-

ics. Wiley, New York, Chap. 5

S. Cottenier

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and

Angle-resolved

Magnetism arises from the spins of electrons in

partially filled outer shells of atoms in a solid which

interact with each other via the exchange interaction.

In a paramagnetic material all electronic states are

degenerate with respect to spin, and consequently are

occupied by two electrons, one with spin up and

one with spin down. The exchange interaction lifts

this degeneracy, lowering the energies of spin up, and

raising those of spin down states. The energy differ-

ence between these states is the exchange splitting.

Therefore, the spin-polarized electronic (band) struc-

ture is the key ingredient for understanding magnet-

ism (see Density Functional Theory: Magnetism).

Photoemission is commonly used to probe the elec-

tronic structure of solids. By also analyzing the spin

polarization of the photoelectrons, information on

the spin-polarized band structure is obtained. One

speaks of electron spin polarization if one can find a

direction in space with respect to which the two pos-

sible spin states are not equally populated. For ferro-

magnetically ordered materials, this direction is

naturally the magnetization direction. The exchange

splitting between majority and minority states of

the same symmetry can be measured directly by spin-

polarized photoemission.

From temperature-dependent measurements, the

change of the band structure on approaching the

Curie temperature can be compared with various

models of the ferro- to paramagnetic phase transi-

tion. The exchange coupling of ultrathin layers ad-

sorbed on ferromagnetic surfaces can be studied. The

origin of oscillating interlayer exchange coupling be-

tween ferromagnetic layers via a nonferromagnetic

interlayer was clarified by spin-resolved photoemis-

sion. The degree of spin polarization at the Fermi

level is important for devices utilizing spin-dependent

transport phenomena. Core-level photoelectron spec-

tra also show spin polarization which can be used as

an element-specific indicator for magnetic order.

While such spectra involving inner shell excitations

do not give direct evidence on the spin-polarized

electronic structure of the partially filled outer

(valence) states, which are the source of magnetism,

indirect information is contained in the line shape,

the degree of spin polarization, and the presence of

satellites. An important aspect of spin-polarized core

level spectroscopy is the possibility of characterizing

the relative spin orientation of different species in a

multicomponent sample because core-level spectra

occur with different excitation energies.

Spin-dependent mean free paths and photoelectron

diffraction effects may have an influence on the

measured spin-resolved photoemission spectra. Apart

from a magnetic ground state, spin–orbit interaction

gives rise to spin polarization in photoelectron spec-

tra. While for valence states this is, in most cases, a

relatively small effect, the large spin orbit interaction

encountered for ionized inner shells with nonzero or-

bital momentum will in general give rise to significant

spin polarization, both for magnetic and nonmag-

netic systems. By choosing a suitable geometry this

effect may be avoided, so that only the exchange-

related effect remains. Alternatively, for magnetic

systems the combined influence of the exchange and

spin orbit interactions leads to magnetic dichroism.

The continuous background of secondary electrons

also is spin-polarized, and the degree of polarization

at low energies can be related to the ground state

magnetic moment.

1. Angle-resolved Photoemission

In a photoemission (PE) experiment, UV or soft

x-rays are used to excite electrons from a sample. In

the excitation process the photon is annihilated, and

energy conservation requires that the total energy is

unchanged,

E

i

þ hn ¼ E

f

þ E

kin

ð1Þ

where E

i

and E

f

are the energies of the initial and final

state of the sample, E

kin

is the energy of the photo-

electron, and hn is energy of the photon (Kevan 1992,

Hu

¨

fner 1995). The difference between E

i

and E

f

is conventionally termed binding energy E

B

.Itis

determined from the photon energy chosen for the

experiment and the measured kinetic energy of the

photoelectron,

E

B

¼ hn E

kin

f

A

ð2Þ

where f

A

is the work function of the sample. The

kinetic energies are usually measured by electro-

static analyzers. For solid metallic samples, the most

weakly bound electrons are those at the Fermi level.

Therefore, the highest kinetic energy photoelectrons

are generated by ejecting electrons from states at the

Fermi level E

F

, and this cut-off is used as reference

(zero) for binding energies such that

E

B

¼ E

kin

E

kin

ðE

F

Þð3Þ

1052

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and Angle-resolved

In addition to energy conservation, momentum al-

so has to be conserved. The relationship between

electron energy and momentum, i.e., the band struc-

ture, leads to pronounced angular dependencies. In

angle-resolved photoemission, the energy distribution

of the photoelectrons is measured as a function of

emission angle in order to obtain information on the

band structure. For making the connection between

measured angle-resolved PE spectra and the band

structure, the sample has to be a single crystal.

Maxima in photoelectron spectra arise whenever the

photon energy matches the energy difference between

an occupied state and an unoccupied state in the

band structure. The components of the photoelectron

wave vector parallel (k

8

) and perpendicular (k

>

)to

the surface are

k

8

½k

>

¼ð2mE

kin

=h

2

Þ

1=2

sin y½cos y

¼0:5123 ðE

kin

=1eVÞ

1=2

(

A

1

sin y½cos yð4Þ

where m is the electron mass, and y the emission an-

gle measured to the surface normal. The parallel

component is conserved (to within a reciprocal lattice

vector) for photoelectrons crossing the surface, so

that k

8

measured in vacuum is identical to that in the

solid.

To interpret the perpendicular photoelectron wave

vector component k

>

measured in vacuum, the rela-

tionship between E and k in the solid and the way in

which the wave functions in the solid and in vacuum

are matched have to be known. Structures in PE

spectra are interpreted assuming that the momentum

is retained within the excitation (‘‘vertical’’ or ‘‘direct

transitions’’). With increasing final state energy, the

allowed final states become more dense, and the finite

angular acceptance of photoelectron spectrometers

integrates over an electron momentum range compa-

rable to the Brillouin zone. Spectra taken under such

conditions may be interpreted in terms of density of

states, which can be obtained from the momentum-

resolved band structure by integration in k-space.

Angular variations may then still arise from diffrac-

tion effects, because the photoelectrons are scattered

by the regular array of atoms in the crystal lattice.

2. Electron Spin Analysis

Electron spin polarization P is defined as

P ¼ðN

up

N

down

Þ=ðN

up

þ N

down

Þð5Þ

where N

up

and N

down

are the numbers of electrons

with spin parallel and antiparallel to a chosen

quantization axis. For magnetic materials the

quantization axis is the direction of sample magnet-

ization. To measure photoelectron spin polarization,

the energy-analyzed photoelectrons are subjected to

a spin-dependent scattering process (Kessler 1985,

Feder 1985). The majority of spin polarimeters derive

their spin dependence from spin–orbit interaction.

The spin of the free electron may couple to the an-

gular momentum in the scattering process, which

gives rise to a spin-dependent contribution to the

scattering potential. This spin-dependent contribu-

tion is generally small. A sizable magnitude of this

effect is usually only found for conditions where the

mean scattering cross section is small, so that the

spin-dependent part becomes significant. In general a

compromise has to be found between the require-

ments of a large analyzing power and a large mean

scattering cross section. For spin–orbit based detec-

tors it is possible in principle to measure both trans-

verse spin components simultaneously.

The optimum scattering energy for so-called Mott

detectors is around 100 kV, and this provides scat-

tering asymmetries between 0.2 and 0.3. Mott detec-

tors have been designed and are commercially

available with scattering energies of around 30 kV.

The lower scattering energy reduces the size, com-

plexity, and cost of such a detector at the expense of

lower asymmetries and scattering efficiency. Low en-

ergy scattering is employed either in a LEED type

arrangement where spin–orbit interaction influences

the scattering efficiency for higher-order LEED

beams scattered from the surface of a heavy materi-

al, or in diffuse scattering off a polycrystalline target

composed of a heavy element. Finally, scattering off

the surface of a magnetized single crystal of iron has

been exploited for spin analysis (Hillebrecht et al.

1992). This technique offers a superior performance

in comparison to Mott detectors. However, it is much

more complicated as it requires careful preparation

of the scattering target. Details are summarized in

Table 1, and can be drawn from the literature.

3. Technical Aspects

The elastic mean free path for electrons in solids is of

the order of 0.5 to 5 nm. Therefore, photoemission is

a highly surface-sensitive technique. Clean surfaces

are prepared in ultrahigh vacuum, e.g., by sputtering

and annealing, cleaving, or deposition. In order to

correlate the angular dependencies of photoemission

with the band structure, single crystalline samples are

required. To exploit fully the potential of the tech-

nique, tunable, monochromatic, and polarized light is

needed, which is readily available at synchrotron ra-

diation sources. Because of the limited elastic mean

free path, photoelectrons undergo numerous inelastic

scattering processes, generating secondary electrons

with reduced energy. This leads to a continuous

background of secondary electrons. For ferromag-

netic materials, this background is also spin-polarized

(Kisker et al. 1982). Photoemission experiments have

to be carried out on remanently magnetized sam-

ples, and the influence of stray fields on the electron

1053

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and Angle-resolved

trajectories has to be excluded. Ultrathin films grown

in situ are easy to magnetize within the film plane,

and have negligible stray fields.

4. 3d Ferromagnets

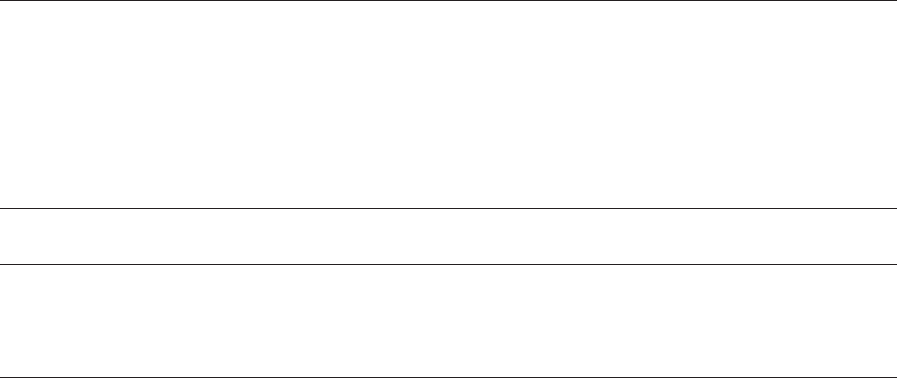

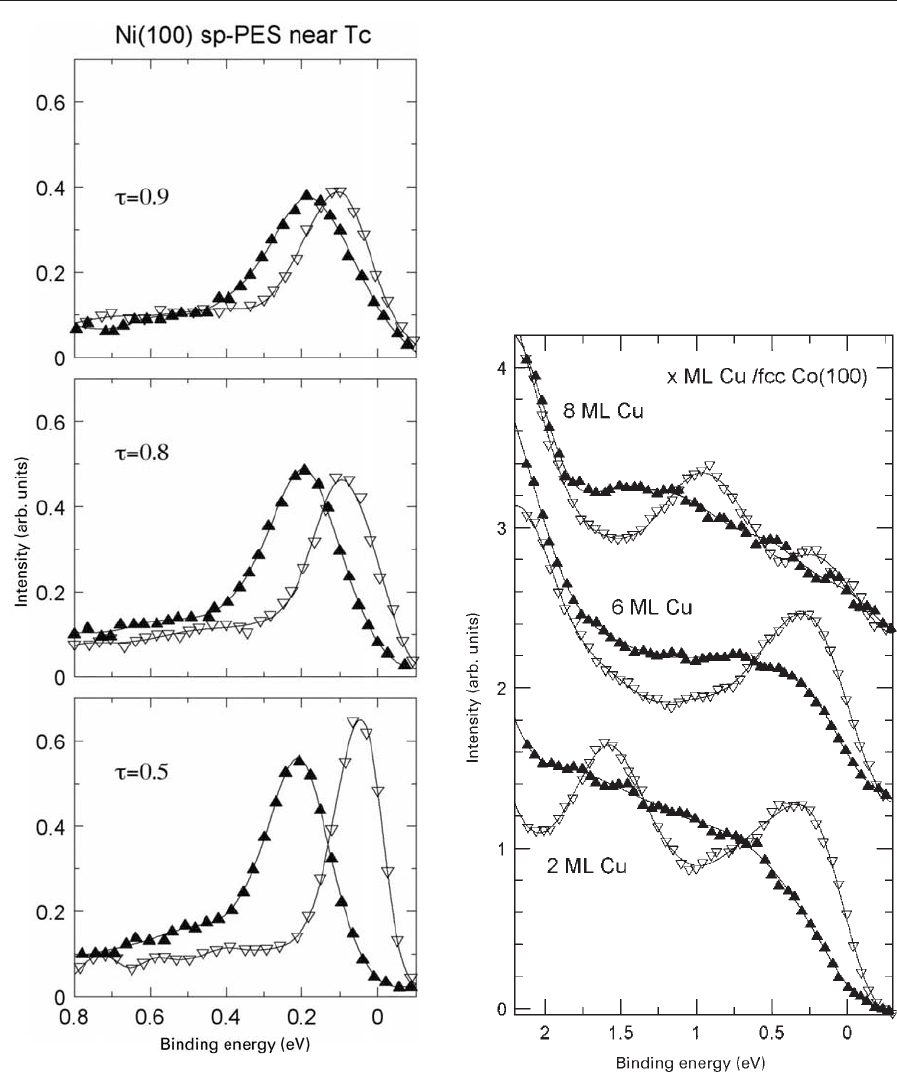

Figure 1 shows spin-resolved photoemission spectra

for iron, cobalt, and nickel taken in normal emission

with 20 eV photons (21.2 eV for cobalt) from single

crystal surfaces. With calculated band structures

available, the features in the spectra can be attribut-

ed to transitions from specific occupied bands, al-

lowing determination of the exchange splitting. In

general, a large number of spectra is taken with dif-

ferent photon energies or for different emission

geometries. The shifts of the peaks observed in such

data sets allow determination of the dispersion of the

electronic bands.

The spectrum for iron (Kisker et al. 1985) shows a

majority peak at 2.6 eV, which is present with small

shifts in binding energy (BE) for all photon energies.

The minority spectrum shows only a weak structure

at the Fermi level, which is attributed to indirect

transitions. The dispersion of the bands close to E

F

causes a majority spin polarization for photon ener-

gies below 33 eV, switching to minority for higher

photon energies.

For the spectrum of h.c.p.-cobalt (Getzlaff et al.

1996), the minority peak is caused by transitions from

bands of D

9

and D

7

symmetry, which cross the Fermi

level and consequently have a high density of states at

E

F

. The peak in the majority spectrum appears at

slightly higher BE. By analyzing the energy and angle

dependence of these structures, an exchange splitting

of 1.6 eV is found, in agreement with calculations.

The spectrum of Ni(110) shows only a sharp struc-

ture at the Fermi level (Ono et al. 1998). At different

photon energies, features up to about 3 eV BE are

observed. This suggests that the bandwidth is smaller

by 30% than the calculated bandwidth. This is as-

cribed to correlation (self energy) effects, which tend

to narrow the bands. The majority and minority peaks

have different binding energies. This reflects directly

the exchange splitting, 0.12 eV in this case. Further-

more, the exchange splitting varies between 0.1 and

0.4 eV for different points in the Brillouin zone.

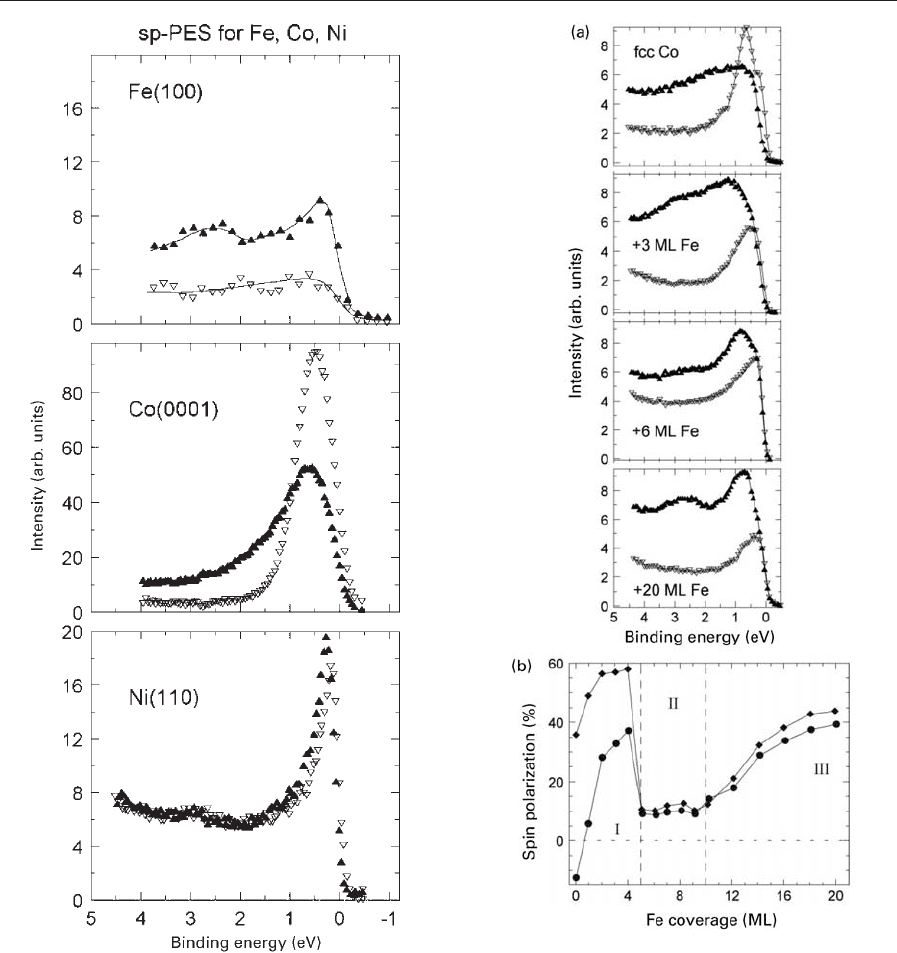

For some applications of ultrathin magnetic films, a

large spin polarization at the Fermi level is desired.

For this purpose, the stabilization of magnetic mate-

rials in different phases is of interest as it permits the

tailoring of magnetic properties at surfaces or inter-

faces for specific applications. Electronic structure cal-

culations suggest that f.c.c.-Fe may show widely

different magnetic properties for small variations of

lattice constant, ranging from nonmagnetic to antif-

erro- and ferromagnetic states. The ferromagnetic

f.c.c. phase is expected to have a higher magnetic mo-

ment than the b.c.c. phase, and may possibly be a

strong ferromagnet, i.e., show complete (100%) spin

polarization at the Fermi level. Figure 2 shows the

evolution of the spin-polarized electronic structure of

iron with different crystal structures (Kla

¨

sges et al.

1998); f.c.c.-iron is grown on f.c.c.-cobalt, which can

be grown in f.c.c.-structure f.c.c.-Cu(100) up to several

hundred monolayers (ML). The initial spectrum shows

the spin-resolved spectrum of cobalt in the f.c.c. phase.

Close to E

F

, one finds a minority polarization, and at

higher BEs the spin polarization changes to majority.

The spectrum for f.c.c.-Fe (3 monolayer film) shows a

majority peak at 2.9 eV and a minority peak at 0.4 eV.

This 2.5 eV splitting can be interpreted as an exchange

splitting. The increased magnitude of this splitting

shows that the magnetic moment is indeed increased

compared with the bulk b.c.c. value.

The reduced spin polarization for the 6 ML film

shows that the major part of the film is ferromag-

netically aligned to the substrate. Nevertheless, the

Table 1

Characteristic parameters of spin polarimeters. If no orientation for the scattering target is given, a polycrystalline one

is used. The spin asymmetry is given by the difference of differential scattering cross sections for the two channels

corresponding to up and down spin electrons, normalized to the sum. The figure of merit, given by the square of the

spin asymmetry times the average scattering cross section, is a measure for the performance of a spin detector; to reach

a certain statistical uncertainty, the data acqusition time varies as the reciprocal of the figure of merit. For the LEED

polarimeters, the performance depends on the crystalline quality of the surface. For VLEED, the polarization is

determined by sequential measurements with reversed target magnetization, which halves the figure of merit

(included).

Type of spin

polarimeter

Operating

energy (eV)

Scattering

target

Spin

asymmetry

Figure of merit

10

4

Mott detector 10

5

Au 0.25 1

Medim energy Mott detector 2–4 10

4

Au 0.2 0.2

Diffuse scattering 150–300 Au 0.07–0.11 1

LEED 105 W(100) 0.27 1.6

VLEED 12 Fe(100) 0.2–0.4 5–10

1054

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and Angle-resolved

Figure 1

Spin-resolved photoemission spectra for the 3d

ferromagnets, taken with 20 eV photons (21.2 eV for

cobalt) in normal emission: data for Fe(100) with

normal light incidence (from Kisker et al. 1985); for

Co(0001) light incidence under 301 to surface normal,

magnetization in the surface plane (Getzlaff et al. 1996);

for Ni(110) light incidence 201 to surface normal (Ono

et al. 1998). For all examples filled triangles pointing up

represent majority spin electrons, empty triangles

pointing down are for minority spin electrons.

Figure 2

(a) Evolution of spin-resolved photoemission spectra for

Fe films grown on f.c.c. Co(100); photon energy 34 eV,

normal emission, plane-polarized light under 451

incidence; (b) spin polarization data for Fe films grown

on f.c.c.-cobalt, derived from the spectra in Fig. 2(a).

The polarization shows three thickness regimes, which

are associated with f.c.c.-Fe (area I), a distorted Fe

phase with low moment (area II), and finally a transition

to b.c.c.-Fe (area III); circles for spin polarization at

0.8 eV binding energy, diamonds for 1.8 eV (from

Kla

¨

sges et al. 1998).

1055

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and Angle-resolved

finite spin polarization demonstrates that the surface

layer is still ferromagnetically aligned to the cobalt

magnetization. A fraction of the surface layer is still

in the high moment state, as can be seen from the

weak structure between 2 and 3 eV. For coverages

above 10 ML, the whole film reverts to the thermo-

dynamically stable b.c.c. structure. The polarization

increases, as the whole film orders ferromagnetically;

however, the exchange splitting of about 2.2 eV is

typical for the b.c.c. moment. Figure 2(b) shows the

polarization measured at different points in the spec-

trum, which tracks very well the magnetic moments

derived from other experiments.

5. Ferro- to Paramagnetic Transition

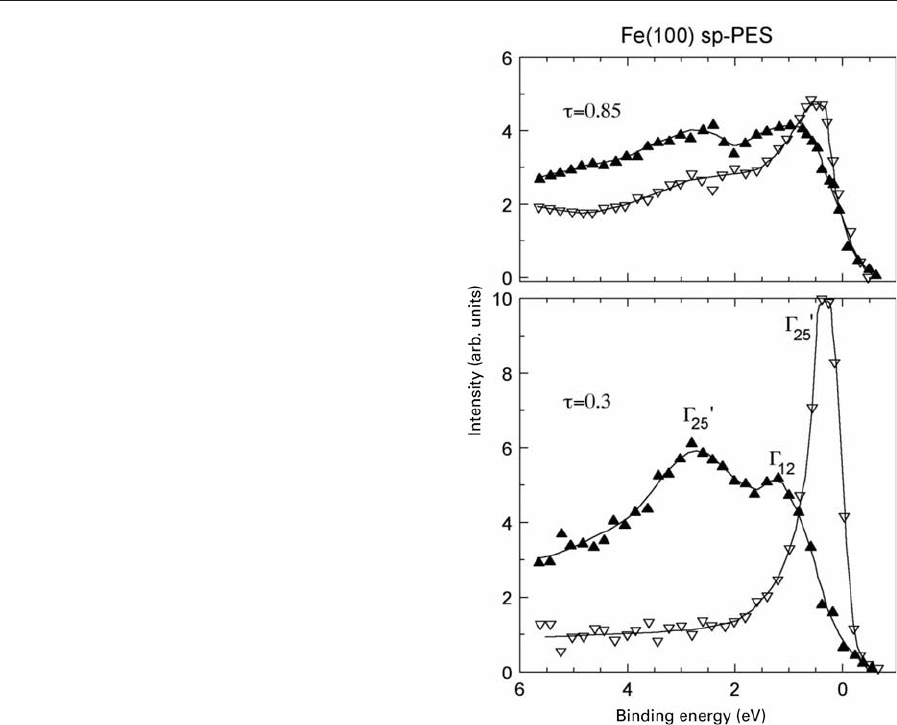

Figure 3 shows the change of the spin-resolved PE

spectrum of b.c.c.-Fe with temperature (Kisker et al.

1984). The key issue for such studies is to gain an

insight into the underlying physics of the transition

from the para- to the ferromagnetic state. While the

spin-averaged spectra do not change significantly on

heating to 0.85 T

C

, the spin-resolved data show sig-

nificant changes: the minority peak at 0.4 eV BE loses

intensity and becomes broader, and the majority spin

peak at 2.6 eV also loses intensity, with nearly un-

changed width and BE. The results show that the

exchange splitting is of the order of 2 eV, and does

not change significantly on approaching the Curie

temperature.

Figure 4 shows similar temperature-dependent da-

ta for Ni(110) (Hopster et al. 1983). The data clearly

show a scaling of the exchange splitting proportional

to the macroscopic magnetization with increasing

temperature, in agreement with the Stoner model. In

contrast, these results are inconsistent with a so-

called local band model, where the decrease of the

magnetization is caused by transverse fluctuations of

microscopic regions which still have the full temper-

ature-independent exchange splitting. By choosing

different excitation conditions, Fujii et al. (1995)

probed a different region of the Brillouin zone. The

results showed aspects of both types of behavior: an

exchange-splitting decreasing with temperature, and

a contribution of the local band model with temper-

ature-independent exchange splitting.

Spin- and angle-resolved photoemission of elemen-

tal 3d ferromagnets has shown that, depending on the

material, different mechanisms are responsible for the

ferro- to paramagnetic transition. The small changes

of the exchange splitting observed for iron can ap-

parently be understood within a local band model,

while the temperature-dependent exchange splitting

found for nickel can be explained within the Stoner

model (see Itinerant Electron Systems: Magnetism

(Ferromagnetism)). This does not rule out that in

each case the nondominant mechanism is to some

extent in operation (Kisker 1984, Fujii et al. 1995).

6. Quantum Well States

The magnetization between two ultrathin films, form-

ing a sandwich with a nonmagnetic layer in-between,

may be coupled by exchange interaction via the non-

magnetic interlayer (Gru

¨

nberg et al. 1986). The cou-

pling strength oscillates periodically with interlayer

thickness between ferro- and antiferromagnetic cou-

pling, and furthermore decays with interlayer thick-

ness. The most widely used material combinations are

Fe–Cr and f.c.c.-Co–Cu (Parkin 1994). The thickness

of the interlayer is up to about 20 monolayers. The

coupling can be understood in terms of a modified

RKKY theory (see Magnetism in Solids: General

Figure 3

Evolution of the spin-polarized photoemission spectrum

of Fe(100) on approaching the Curie temperature

T

C

¼1043 K (Kisker et al. 1984). Photon energy 60 eV,

normal emission, s-polarized light; lower panel for

temperatures t ¼T/T

C

¼0.3, upper for t ¼T/T

C

¼0.85;

triangles pointing up for majority states.

1056

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and Angle-resolved

Introduction), which was originally proposed to des-

cribe the interaction between magnetic impurities in

nonmagnetic host materials. In this picture, the os-

cillation period of the coupling is related to the size

and shape of the Fermi surface of the nonmagnetic

interlayer. The oscillation period is given by 2p=k

N

,

where k

N

is a Fermi surface nesting vector of the bulk

band structure of the interlayer material. The small

thickness of the interlayer may lead to quantization

of the bulk bands in the direction normal to the film.

This affects in particular the sp-like states of copper,

which in bulk copper metal are free electron-like.

Figure 5 shows spin-resolved photoemission spectra

Figure 4

Evolution of the normal emission spin-polarized

photoemission spectrum of Ni(110) on approaching the

Curie temperature T

C

¼627 K; t ¼T/T

C

; photon energy

16.8 eV, probing the X point (Hopster et al. 1983).

Figure 5

Spin-resolved photoemission from sp-like quantum well

states of ultrathin copper grown on f.c.c.-Co(100)

(Garrison et al. 1993).

1057

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and Angle-resolved

for ultrathin copper films on Co(100) (Garrison et al.

1993).

The copper d states have binding energies of 2 V or

more, so that the region shown is dominated by cop-

per sp-like states (with some residual emission from

cobalt d states for the lowest copper coverage). The

minority (with respect to cobalt majority) spectra

show clearly discrete states that occur with different

binding energies for different coverages. In contrast,

the majority states do not show discrete states, indi-

cating that the quantum well states are strongly

minority-polarized. Depending on the thickness of

the copper layer, the quantum well states occur at

different energies for certain thicknesses at the Fermi

level. The intensity and spin polarization at the Fermi

level oscillate with thickness, and this oscillation

correlates directly with the oscillation of the inter-

layer exchange coupling between two f.c.c.-Co films

separated by a copper film (Carbone et al. 1993).

These experiments show that the spin polarization of

the quantum well states induced by the confining

magnetic interface causes the interlayer exchange

coupling.

7. Spin-resolved Photoemission from Core Levels

Inner shells are completely filled, and consequently

the total spin and angular momentum is always zero.

This means that the integrated spectrum should have

no spin polarization. However, ejection of an electron

from an inner shell generates a hole which has a spin

and, if one is not looking at an s level, an angular

momentum. In a magnetic system, the spin of the

core hole couples to the spin of valence electrons, and

this may lead to different excitation energies depend-

ing on the spin of the photoelectron. From studies of

the 3d ferromagnets it is known that at the leading

edge of a core level spectrum one always finds mi-

nority spin polarization. One may state this as a gen-

eralized Hund’s rule (see Magnetism in Solids:

General Introduction), because minority spin for the

photoelectron means that the spin of the remaining

shell from which one electron is removed has major-

ity character, i.e., is parallel to the spin of the ma-

jority electrons. Core level spin polarization can be

used as an element-specific indicator of magnetic or-

der. For a number of nonferromagnetic elements

theoretical calculations predict a ferromagnetic

ground state for a monolayer film of this element.

A famous example is antiferromagnetic chromium,

which in the bulk has a mean magnetic moment of

0.6 m

B

. For a chromium monolayer on iron an en-

hanced moment of 3.6 m

B

was derived, with ferro-

magnetic order within the chromium layer, coupled

antiferromagnetically to the ferromagnetic iron

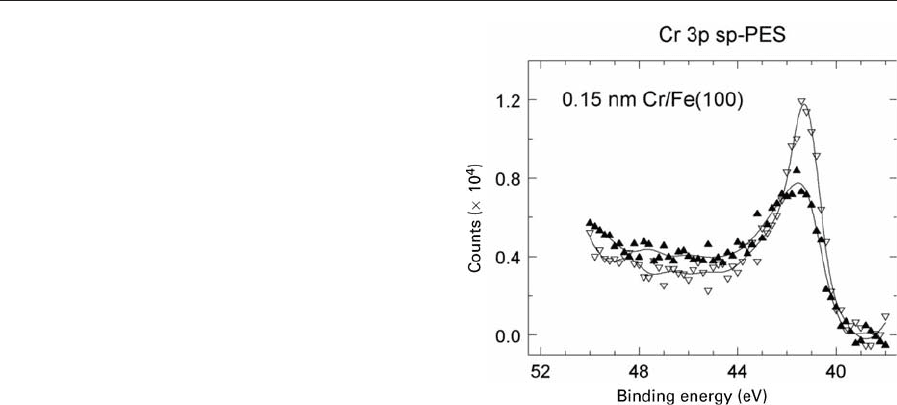

substrate. Figure 6 shows a spin-resolved chromium

3p photoemission spectrum taken for a monolayer

(0.15 nm) of chromium on Fe(100) (Hillebrecht et al.

1992). The spectrum shows a large spin polarization,

which is opposite to that of the 3p spectrum of the

iron substrate. This demonstrates the antiferromag-

netic coupling between the iron surface and the chro-

mium overlayer. The magnitude of the chromium 3p

polarization indicates that the chromium moment is

smaller than the predicted 3.6 m

B

. This is caused by

structural intermixing between chromium and iron

atoms occurring during chromium deposition, lead-

ing to a higher chromium coordination.

Bibliography

Carbone C, Vescovo E, Rader O, Gudat W, Eberhardt W 1993

Exchange split quantum well states of a noble metal film on a

magnetic substrate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 2805–8

Feder R 1985 Polarized Electrons at Surfaces. World Scientific,

Singapore

Fujii J, Kakizaki A, Shimada K, Ono K, Kinoshita T, Fukutani

H 1995 Temperature dependence of the spin- and angle-

resolved valence band photoemission spectra of Ni(110).

Solid State Commun. 94, 391–5

Garrison K, Chang Y, Johnson P D 1993 Spin polarisation of

quantum well states in copper thin films deposited on a

Co(001) substrate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 2801–5

Getzlaff M, Bansmann J, Braun J, Scho

¨

nhense G 1996 Spin

resolved photoemission study of Co(0001) films. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater. 161, 70–88

Gru

¨

nberg P, Schreiber R, Pang Y, Brodsky M B, Sowers H

1986 Layered magnetic structures: evidence for antiferro-

magnetic coupling of Fe layers across Cr interlayers. Phys.

Rev. Lett. 57, 2442–5

Figure 6

Spin-resolved 3p core level photoemission for 1.5 nm

Cr/Fe(100) (from Hillebrecht et al. 1992). Photon energy

117 eV, normal incidence and emission. A constant

background, matched to the spectrum on the low

binding energy side, was substracted from the spectrum.

1058

Photoemission: Spin-polarized and Angle-resolved

Hillebrecht F U, Roth C, Jungblut R, Kisker E, Bringer A 1992

Antiferromagnetic coupling of a Cr overlayer to Fe(100).

Europhys. Lett. 19, 711–6

Hopster H, Raue R, Gu

¨

ntherodt G, Kisker E, Clauberg R,

Campagna M 1983 Temperature dependence of the exchange

splitting in Ni studied by spin-polarized photoemission. Phys.

Rev. Lett. 51, 829–32

Hu

¨

fner S 1995 Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Springer, Berlin

Kessler J 1985 Polarized Electrons, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin

Kevan S D 1992 Angle-resolved Photoemission: Theory and

Current Applications. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Kisker E 1984 Photoemission and finite temperature magnetism

of Fe and Ni. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 45, 23–32

Kisker E, Gudat W, Schro

¨

der K 1982 Observation of a high-

spin polarization of secondary electrons from single crystal

Fe and Co. Solid State Commun. 44, 591–5

Kisker E, Schro

¨

der K, Campagna M, Gudat W 1984 Temper-

ature dependence of the exchange splitting of Fe by spin re-

solved photoemission with synchrotron radiation. Phys. Rev.

Lett. 52, 2285–8

Kisker E, Schro

¨

der K, Gudat W, Campagna M 1985 Spin po-

larized angle resolved photoemission study of the electronic

structure of Fe(100) as a function of temperature. Phys. Rev.

B 31, 329–39

Kla

¨

sges R, Schmitz D, Carbone C, Eberhardt W, Kachel T

1998 Surface magnetism and electronic structure of ultrathin

fcc Fe films. Solid State Commun. 107, 13–8

Ono K, Kakizaki A, Tanaka K, Shimada K, Saitoh Y, She-

ndohda T 1998 Electron correlation effects in ferromagnetic

Ni observed by spin- and angle-resolved photoemission. Solid

State Commun. 107, 153–7

Parkin S S P 1994 Giant magnetoresistance and oscillatory in-

terlayer exchange coupling in polycrystalline transition metal

multilayers. In: Heinrich B, Bland J A C (eds.) 1994 Ultrathin

Magnetic Structures. Springer, Berlin, Vol. 2

F. U. Hillebrecht

Heinrich-Heine-Universita

¨

tDu

¨

sseldorf, Germany

Photomagnetism of Molecular Systems

Photoreactivity is a widespread phenomenon in

organic and inorganic chemistry. A compound

may change its structural and/or electronic proper-

ties under light irradiation. Light-induced charge

separation or cis–trans isomerization processes under

light are well-known examples. A phase transforma-

tion may occur, with or without hysteresis. If the

light-induced new phase possesses sufficiently long

lifetime and differs in optical and/or magnetic pro-

perties such that it can be easily detected by optical or

magnetic means, the material bears the potential for

possible technical applications in switching or display

devices.

This article deals with light-induced changes of the

magnetic and/or optical properties of transition metal

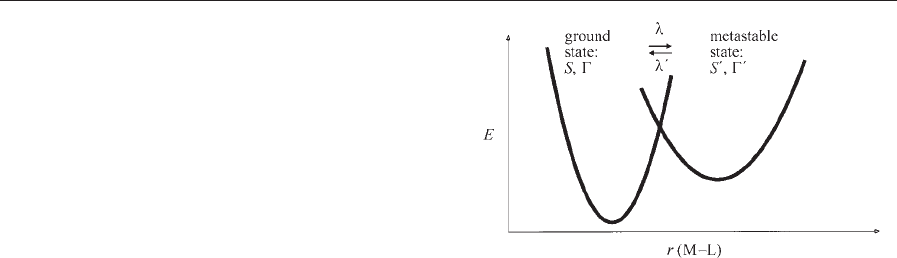

compounds to long lived metastable states. Figure 1

sketches the general situation: A complex compound

with ground state spin S and orbital momentum G

converts under light of wavelength l, to a more or

less metastable state with different spin and orbital

momentum S

0

and G

0

. The metastable state lies higher

in energy and usually has weaker metal–ligand (M–L)

bonds and accordingly longer bond lengths r(M–L)

than the ground state. This is the consequence of

an increasing population of antibonding molecular

orbitals and simultaneously decreasing population

of weakly p-backbonding molecular orbitals. The

energy barrier between the potential wells governs

the lifetime of the metastable state, which in turn

depends on the horizontal and vertical displace-

ments relative to each other. Switching back from the

metastable state to the ground state may be possible

by using light of different wavelength l

0

. The two-

potential-well scheme of Fig. 1 refers to transition

metal complexes with strong and intermediate field

strength ligands. In weak-field complexes the poten-

tial with the longer M–L bond length would be

the ground state, but light-induced switching is still

possible.

There are various classes of transition metal com-

pounds which all show light sensitive electronic struc-

ture changes accompanied by drastic changes of their

magnetic and/or optical properties. Among the best

known and extensively studied systems are those

exhibiting:

*

metal-centered thermal spin transition, e.g., spin

crossover (SC) complexes of iron(II);

*

metal-to-ligand charge transfer, e.g., nitroprus-

side complexes;

*

metal-to-metal charge transfer, e.g., Prussian

blue analogues;

*

ligand isomerization with change of spin state,

e.g., stilbenoid complexes;

*

valence tautomerism, e.g., catecholate com-

plexes of cobalt(II).

Figure 1

Schematic representation of the potential wells for the

ground state with quantum numbers S and G and

metastable state (S

0

and G

0

) for a transition metal

compound. The switching process between these states

may be provoked by irradiation with light of wavelength

l,orl

0

for the reverse process.

1059

Photomagnetism of Molecular Systems