Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

where V

0

is the volume of unit cell, index j numerates

the branches of the dispersion relation _o

j

ð

~

qÞ;

~

q is

the phonon momentum, and the integral is taken

within the first Brillouin zone. The detailed theory of

nuclear inelastic scattering has been published by

several authors (Singwi and Sjo

¨

lander 1960; Kohn

et al. 1998, Sturhahn and Kohn 1999).

From the density of phonon states other

(thermo)dynamic quantities can be derived as the vi-

brational contribution to the internal energy, lattice

specific heat at constant volume and pressure, vibra-

tional entropy. From the sum rules (Lipkin 1999) the

density of phonon states, f

LM

and the mean square

displacement, the mean kinetic energy, the mean

force constant, and the second order Doppler shift

can be determined.

In summary, NIS gives direct access to the density

of phonon states and various (thermo)dynamic quan-

tities. It is complementary to methods as inelastic

neutron, x-ray, and light scattering. In those tech-

niques mainly dispersion relations which are fitted to

a model are measured and in a final step the density

of phonon states can be derived.

2. Applications

2.1 Applications to High Pressure

High-pressure applications are one of the domains

which benefit most from the outstanding properties

of synchrotron radiation. The small beam size allows

one to work with samples much smaller than 100 mm

in diameter. In that case state-of-the-art diamond

anvil cells (DAC) are able to reach pressures far

above the 100 GPa regime, those pressures which are

common in the center of the Earth. The small diver-

gence of the beam allows sophisticated sample envi-

ronments, in situ pressure calibration and diffraction

studies for the determination of the induced volume

change with pressure. In the following example iron

metal has been investigated by NFS and NIS in order

to follow over the pressure-induced phase transition

magnetic order (via the hyperfine field) and structural

dynamics (via the partial phonon DOS).

(a) Iron metal

Recently, the high-pressure behaviour of iron gained

much interest due to unusual superconductivity and

due to simulations of the inner core of the Earth and

improved technical developments in high-pressure

research. It is well known that a-iron undergoes un-

der pressure a magnetic and structural phase transi-

tion to the hexagonal closed-packed (h.c.p.) phase of

iron (e-iron) in the pressure range of 10–22 GPa at

ambient temperature.

A 2.5 mm thick iron foil enriched to 95% in

57

Fe

was pressurized in a DAC (Gru

¨

nsteudel 1997).

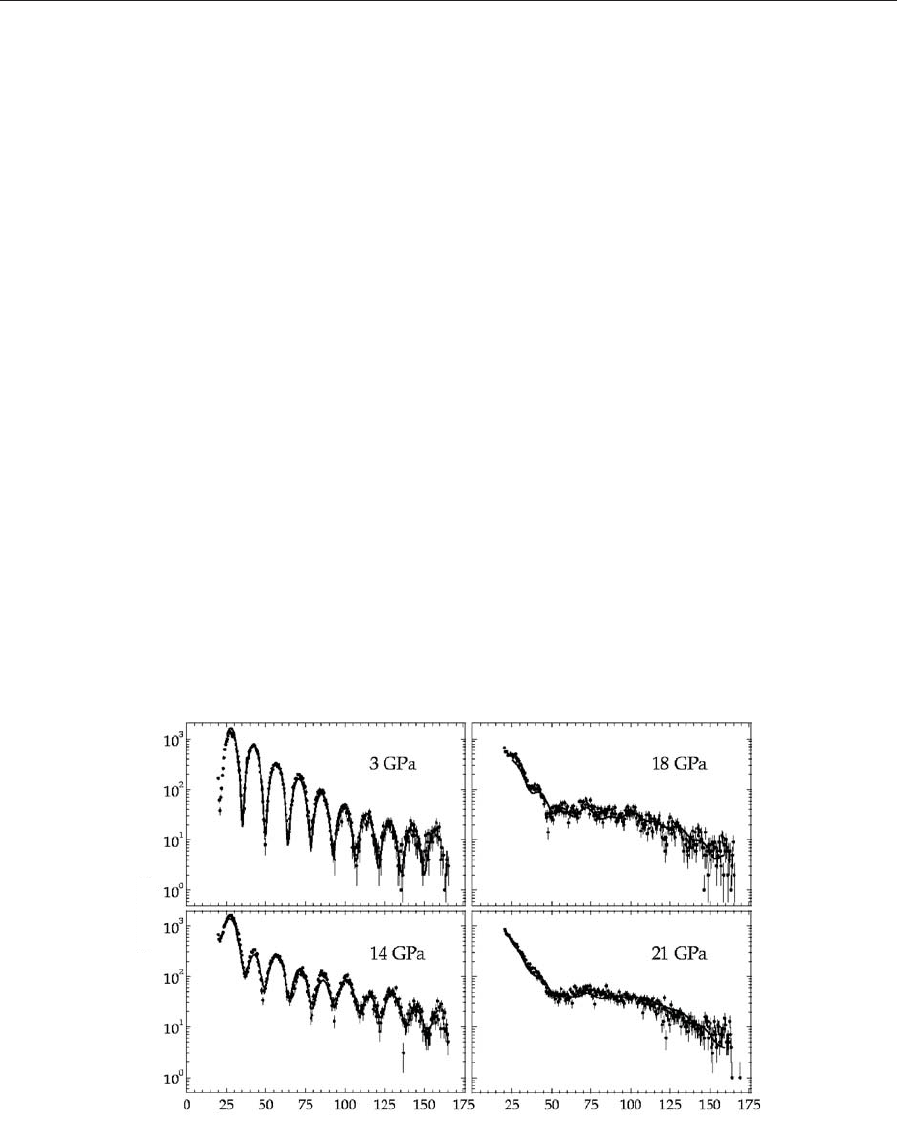

Figure 5 shows the NFS spectra for various pres-

sures. A small external magnetic field (0.6 T) aligned

the internal field perpendicular to the incoming wave

vector k

!

and the polarization

~

E (the case discussed

in Fig. 3a). At 3 GPa the spectrum reveals iron in the

pure a-phase. The regular quantum beat pattern

shows a single frequency from which a hyperfine field

Time after excitation (ns)

Intensity

Figure 5

Time spectra of NFS from the pressure induced a-e transition in Fe at various pressures (from Gru

¨

nsteudel 1997).

1000

Nuclear Resonance Scattering

of 32.4 T can be derived. Taking into account the

polarizing external field of 0.6 T the internal field be-

comes 33.0 T (in case of iron the external and internal

field align antiparallel). At 14 GPa the influence of the

e-phase is already quite pronounced. With a further

increase in pressure the influence of the nonmagnetic

e-phase becomes dominant. At 21 GPa the sample is

almost completely in the e-phase. Now the NFS

spectrum is modified only by a single Bessel minimum

at 50 ns which originates from the increased effective

thickness in comparison to that of the magnetically

split one.

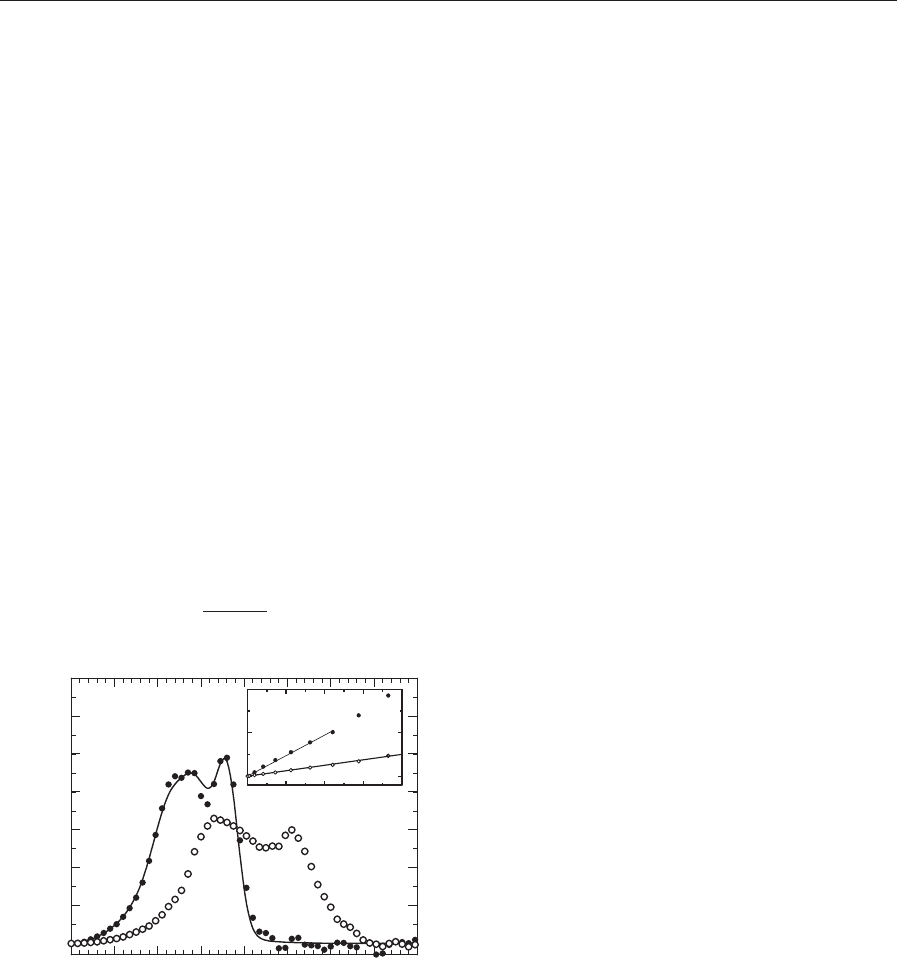

With the same sample, NIS spectra have been re-

corded and the densities of phonon states have been

extracted (Lu

¨

bbers et al. 2000b). Examples at ambi-

ent pressure and at 42 GPa are displayed in Fig. 6. All

spectral features of the density of phonon states of

e-Fe are shifted to higher energies with respect to

a-Fe revealing a hardening of the lattice vibrations.

Several thermodynamical properties have been

derived as f

LM

and the mean-square displacement,

respectively, the mean phonon energy and the corre-

sponding Debye temperature, the lattice contribution

to the specific heat c

V

, the internal energy, entropy,

and the mean force constant. Finally, from the low-

energy part of the density of phonon states the

average velocity of sound v

av

(Fig. 6 inset) has been

derived according to the relation

gðEÞ¼

V

2p

2

_

3

v

3

av

E

2

ð10Þ

with V the volume per Fe atom. Extensions to higher

pressures have been reported (Mao et al. 2001) and

investigations undertaken to account for anisotropies

(Lu

¨

bbers et al. 2000a). These sound velocity data

have been complemented by recent data-from inelas-

tic x-ray scattering and in the very high-pressure

regime by those from shock waves and in the low-

pressure regime by those from neutron scattering.

2.2 Applications to Nano-structured Material

The understanding of magnetism of self-organized

nano-structures and clusters gained much attention

because of fundamental aspects of nanoscale magnetic

ordering in general and possible applications in high-

density magnetic storage and magnetoelectronics.

(a) Iron on W (110)

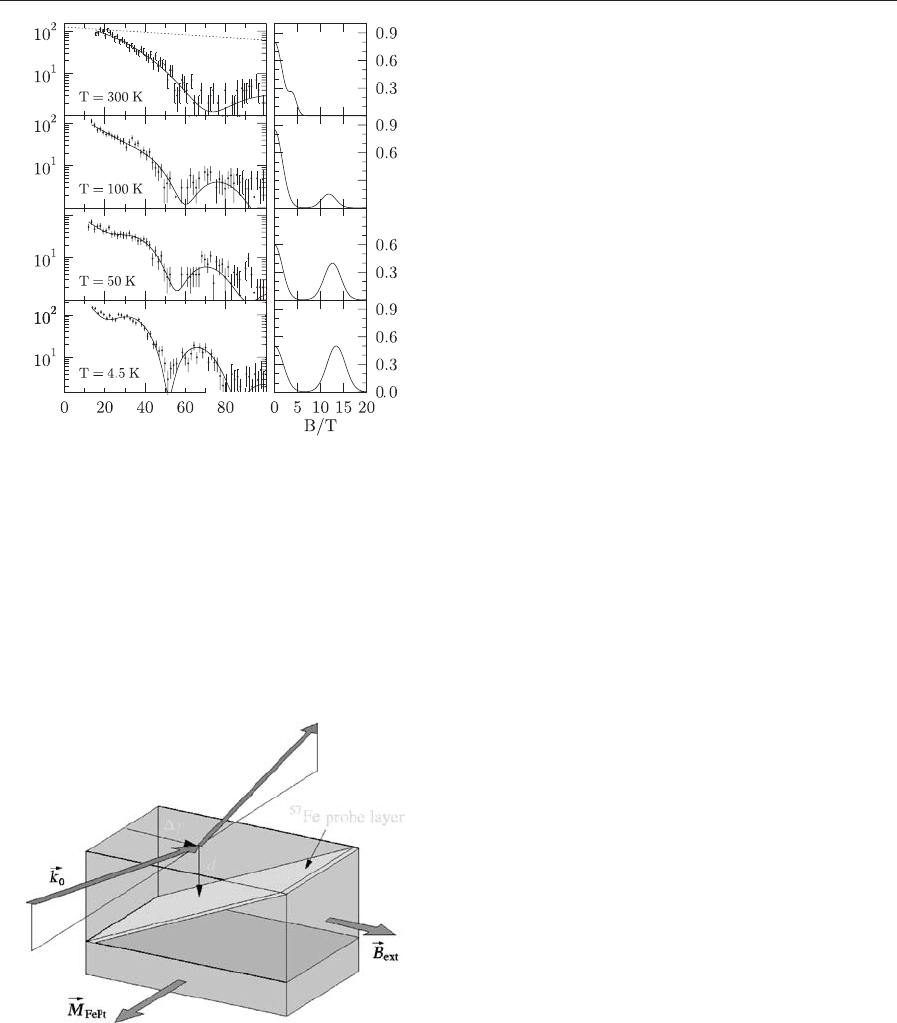

As an example the perpendicular spin orientation in

ultrasmall Fe islands on W (110) will be discussed

(Ro

¨

hlsberger et al. 2001). Ultrasmall pseudomorphic

Fe islands on an atomically clean W (110) crystal have

been prepared by thermal evaporation of Fe enriched

to 95% in

57

Fe. The coverage of the Fe islands was

0.57 which is slightly below the percolation limit.

Their average diameter was determined to be 2.0 nm.

A coating of five monolayers of Ag prevents the sam-

ple from contamination. Figure 7 left panel displays

the time spectra taken in grazing incidence geometry

between 300 K and 4.5 K. The right panel of Fig. 7

shows the determined weight of the magnetic compo-

nent. It increases with decreasing temperature. This

can be attributed to superparamagnetic relaxation of

the magnetic moments. At high temperatures the

magnetization of small particles is subject to fast

thermal fluctuations so that the effective magnetic

hyperfine field averages to zero. The transition from

the fast relaxation regime to the magnetically ordered

state occurs at about 50 K. However, it is a very broad

transition certainly due to the size distribution of the

islands. The modulation in the time spectra is char-

acteristic for a perpendicular magnetization. This re-

sult is quite remarkable because Fe films on W (110)

are known to be magnetized in-plane for coverages of

more than 0.6.

(b) Exchange-coupled thin films

Exchange-coupling between soft- and hard-magnetic

phases (see Multilayers: Interlayer Coupling) plays

an important role in the engineering of novel func-

tional magnetic nanostructures. There exist some

micromagnetical models describing this behavior

(see Magnets: Remanence-enhanced), however, due

to methodological difficulties there exist nearly no

direct measurements of the actual spin structure.

Utilizing the technique of probe layers, i.e., inserting

57

Fe in various depths of the thin film (see Fig. 8),

0 50 100 150 200

E

2

(meV

2

)

g(E)/(1/meV)

g (E)

0

10 20 30 40 50

60

70 80

Energy (meV)

0.0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

0.07

Figure 6

Phonon density of states from the pressure induced a-e

transition in Fe at ambient pressure (solid circles) and

42 GPa (open circles). The solid line represents the DOS

from neutron scattering. The inset displays the

corresponding low energy part for the determination of

sound velocities. Here the solid lines represent a linear fit

to the data (reprinted with permission from Lu

¨

bbers

et al. (2000b); r AAAS).

1001

Nuclear Resonance Scattering

NRS directly probes the actual spin structure in var-

ious depths by selectively exciting the

57

Fe layer at

various lateral positions (Ro

¨

hlsberger et al. 2002).

The sample investigated here is a bilayer system con-

sisting of 11 nm Fe on 30 nm Fe

55

Pt

45

in the hard-

magnetic tetragonal L1

0

phase. A wedge-shaped

0.7 nm thick

57

Fe film with a slope of 0.5 nm/mm

has been produced. Different depths d in the sample

can thus be probed by adjusting the displacement Dy

of the sample transversely to the incident beam. The

sample was magnetically saturated in an external field

of 2.3 T so that the remanent magnetization

~

M

FePt

of

the Fe

55

Pt

45

layer was oriented along

~

k

0

, as shown in

Fig. 8. Time spectra at 4 K with selected in-plane ex-

ternal fields

~

B

ext

perpendicular to

~

k

0

were taken at

various displacements of Dy. Evaluation of the spec-

tra reveals the depth dependence of the rotation of

the magnetization in the Fe film (see Fig. 9).

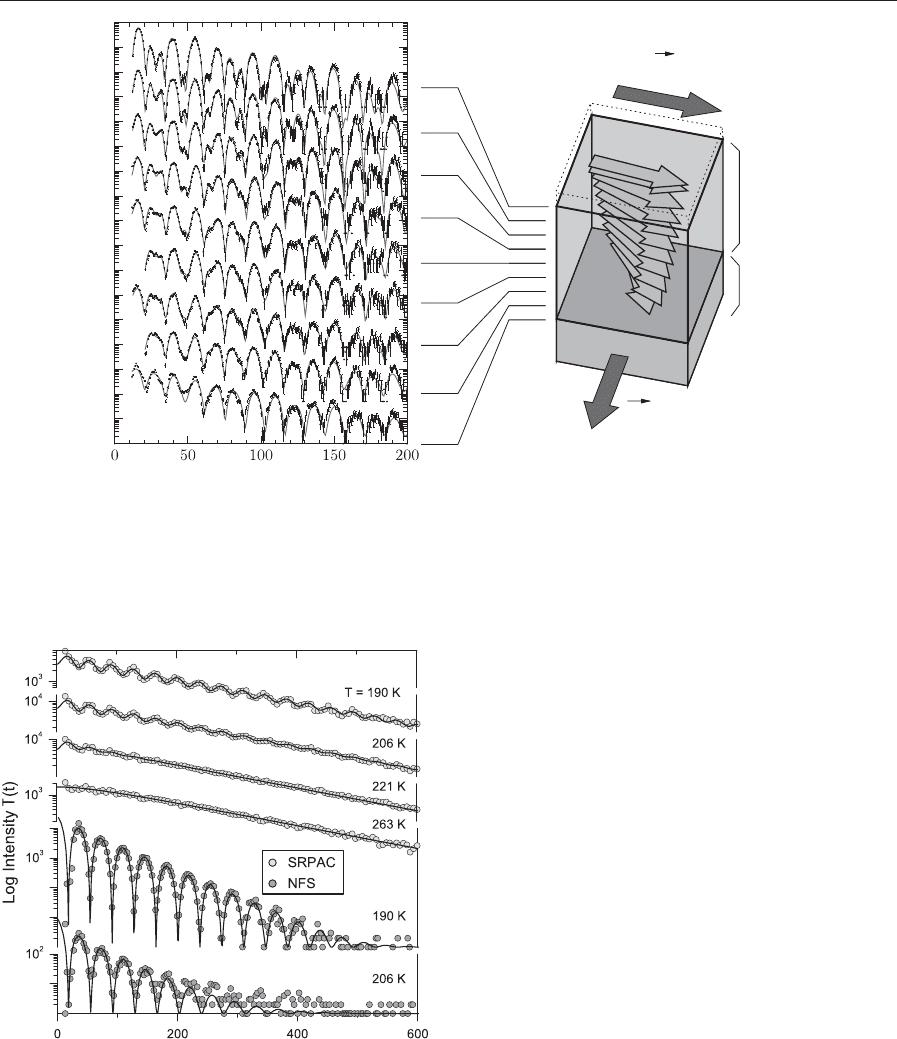

2.3 Applications to Disordered Systems

NRS techniques are well suited for the investigation

of the dynamics of disordered systems over a huge

timescale. Whereas NIS covers the fast regime of

phonons, NQES techniques complement the investi-

gations to the slow time regime (10

5

–10

10

Hz). The

technique of probe molecules allows for the investi-

gation of glasses which do not contain Mo

¨

ssbauer

atoms and, furthermore, when carefully chosen, al-

lows for mode selectivity as collective and noncollec-

tive modes, respectively. In the following example, the

glass forming dibutyl phthalate (DBP), with a glass

temperature T

g

¼178 K, was investigated by NFS

(sensitive to translational and rotational dynamics)

and SRPAC (sensitive only to rotational dynamics)

(Sergueev et al. 2003). Ferrocene was used as probe

molecules. NFS spectroscopy is applicable as long as

the Lamb–Mo

¨

ssbauer factor f

LM

is greater than zero,

which holds in this case up to 210 K. SRPAC, on the

other hand, does not depend on f

LM

and can be ap-

plied in the entire temperature regime (see Fig. 10). At

the lower temperatures, the SRPAC intensity follows

an exponential decay modulated by quantum beats.

In the regime of slow relaxation, the beats are damped

at a rate proportional to rotational relaxation (see

Eqn. (4)). Similar quantum beats modulate the decay

of the NFS intensity, where the damping depends on

the sum of rotational and translational relaxation (see

Eqn. (2)). At higher temperatures, in the regime of

fast relaxation, only SRPAC spectra can be measured.

From these spectra relaxation rates have been deter-

mined. Below 190 K the data sets from both tech-

niques coincide, which means that translational

dynamics is absent in the experimental time window.

Above 190 K the NFS data begin to deviate from

the SRPAC data because translational dynamics is

activated. From these results the pure translational

relaxation rates have been derived.

Figure 8

Scattering geometry of the sample (11 nm Fe on FePt).

The incoming x-ray beam with wavevector

~

k

0

impinges

the sample at a lateral position Dy probing the spin

structure via the wedge-shaped

57

Fe probe layer (0.7 nm)

at depth d (reprinted figure with permission from

Ro

¨

hlsberger et al. (2002); r by the American Physical

Society).

Wei

g

ht

Counts

Time (ns)

Figure 7

Time spectra of nuclear resonant grazing-incidence

reflection from ultrasmall

57

Fe islands on W (110). The

modulation of the intensity is attributed to a

perpendicular magnetization of the Fe islands. The solid

lines are the results of simulations. The right panel

displays the probability density for the hyperfine field

distribution that was obtained from the simulations

(reprinted figure with permission from Ro

¨

hlsberger et al.

(2001); r by the American Physical Society).

1002

Nuclear Resonance Scattering

2.4 Summary

With the advent of powerful synchrotron radiation

sources around the world as APS (Argonne, USA),

SPring-8 (Harima, Japan), and ESRF (Grenoble,

France) nuclear resonance scattering techniques be-

came a rapid growing spectroscopy with unique ap-

plications in various fields. The probe molecule/layer

technique, the application of sophisticated sample

environments, and the possibility of applying various

NRS techniques simultaneously makes this spectro-

scopy a unique tool. The previous typical examples

demonstrate the versatility and huge potential of the

technique. Even when these examples focused on

57

Fe

for the sake of simplicity the tunable (in energy) syn-

chrotron radiation allows for a convenient and rou-

tine access to various Mo

¨

ssbauer isotopes.

See also: Magnetism: Applications of Synchrotron

Radiation; Magnetic Excitations in Solids

Bibliography

Chumakov A I, Ru

¨

ffer R, Gru

¨

nsteudel H, Gru

¨

nsteudel H F,

Gru

¨

bel G, Metge J, Leupold O, Goodwin H 1995 Energy

dependence of nuclear recoil measured with incoherent

nuclear scattering. Europhys. Lett. 30, 427–30

2

4

6

8

10

12

0

16

14

11 nm Fe

FePt

∆y (mm)

3 nm Ag

M

FePt

B

ext

Time (ns)

Log (Intensity)

Figure 9

Left panel: Time spectra of nuclear resonant grazing-incidence reflection from the probe layer (

~

B

ext

¼ 160 mT and at

4 K). Right panel: Image of the derived spin structure (blue arrows) of the iron layer (reprinted figure with permission

from Ro

¨

hlsberger et al. (2002); r by the American Physical Society).

Time

(

ns

)

Figure 10

Time spectra of SRPAC and NFS for several

temperatures from ferrocene in DBP. The solid lines

show the fit according to the full theory (from Sergueev

et al. 2003).

1003

Nuclear Resonance Scattering

Chumakov A I, Sturhahn W 1999 Experimental aspects of in-

elastic nuclear resonance scattering. Hyperfine Interactions

123/124, 781–808

Dattagupta S 1976 Effect of molecular motions in liquids on

Mo

¨

ssbauer relaxation spectra. Phys. Rev. B 14, 1329–32

Gerdau E, de Waard H (eds.) 1999/2000 Nuclear Resonant

Scattering of Synchrotron Radiation. Baltzer Science Pub-

lishers

Gerdau E, Ru

¨

ffer R, Winkler H, Tolkdorf W, Klages C,

Hannon J P 1985 Nuclear Bragg diffraction of synchrotron

radiation in yttrium iron garnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 835–8

Gru

¨

nsteudel H 1998 Nuclear Resonant Scattering of Synchro-

tron Radiation on Iron Containing Biomimetic Compounds.

PhD thesis, Medizinische Universia

¨

tzuLu

¨

beck, Lu

¨

beck

Gru

¨

nsteudel HF 1997 Der a-e-U

¨

bergang in Eisen als Beispiel fu

¨

r

nukleare Vorwa

¨

rtsstreuung von Synchrotronstrahlung an Pro-

ben unter hohem Druck. PhD thesis, Universia

¨

t Paderborn,

Paderborn

Kohn V G, Chumakov A I, Ru

¨

ffer R 1998 Nuclear resonant

inelastic absorption of synchrotron radiation in an aniso-

tropic single crystal. Phys. Rev. B 58, 8437–44

Leupold O, Rupprecht K, Wortmann G 2003 Electronic and

magnetic transitions in europium compounds studied by nu-

clear forward scattering of synchrotron radiation. Structural

Chemistry 14, 97–107

Lipkin H J 1999 Mo

¨

ssbauer sum rules for use with synchrotron

sources. Hyperfine Interactions 123/124, 349–66

Lu

¨

bbers R, Giefers H, Rupprecht K, Wortmann G, Chumakov

A I 2000a High-pressure phonon spectroscopy of oriented

hcp iron. ESRF Highlights 2000, 48–9

Lu

¨

bbers R, Gru

¨

nsteudel H F, Chumakov A I, Wortmann G

2000b Density of phonon states in iron at high pressure.

Science 287, 1250–2

Mao H K, Xu J, Struzhkin V V, Shu J, Hemley R J, Sturhahn

W, Hu M Y, Alp E E, Vocadlo L, Alfe

´

D, Price G D, Gillan

M J, Schwoerer-Bo

¨

hning M, Ha

¨

usermann D, Eng P, Shen G,

Giefers H, Lu

¨

bbers R, Wortmann G 2001 Phonon density of

states of iron up to 153 gigapascal. Science 292, 914–6

Ro

¨

hlsberger R, Bansmann J, Senz V, Jonas K-L, Bettac A,

Leupold O, Ru

¨

ffer R, Burkel E, Meiwes-Broer K-H 2001

Perpendicular spin orientation in ultrasmall Fe islands on

W(110). Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5597–600

Ro

¨

hlsberger R, Thomas H, Schlage K, Burkel E, Leupold O,

Ru

¨

ffer R 2002 Imaging the magnetic spin structure of ex-

change-coupled thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 237201

Sergueev I, van Bu

¨

rck U, Chumakov A I, Asthalter T, Smirnov

G V, Franz H, Ru

¨

ffer R, Petry W 2003 Rotational and

translational dynamics studied by nuclear resonant scatter-

ing. ESRF Highlights 2003, 12–3

Seto M, Yoda Y, Kikuta S, Zhang X, Ando M 1995 Obser-

vation of nuclear resonant scattering accompanied by pho-

non excitation using synchrotron radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett.

74, 3828–31

Singwi K, Sjo

¨

lander A 1960 Resonance absorption of nuclear

gamma rays and the dynamics of atomic motions. Phys. Rev.

120, 1093–102

Sturhahn W, Kohn V G 1999 Theoretical aspects of incoherent

nuclear resonant scattering. Hyperfine Interactions 123/124,

367–99

Sturhahn W, Toellner T, Alp E E, Zhang X, Ando M, Yoda Y,

Kikuta S, Seto M, Kimball C, Dabrowski B 1995 Phonon

density of states measured by inelastic nuclear resonant scat-

tering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3832–5

R. Ru

¨

ffer

ESRF, Grenoble, France

1004

Nuclear Resonance Scattering

Optical and Magneto-optic Data Storage:

Channels and Coding

The data path of an optical recording system is ef-

fectively a communications channel with certain

bandwidth and noise characteristics. Data to be re-

corded must pass through this channel and, on re-

play, must emerge unaltered. The vehicle to navigate

the data through the channel is a recording code (also

known as a modulation code or channel code). The

recording code converts data to an appropriate for-

mat to pass through the channel and be recovered as

the original data on replay.

The frequency response of the channel falls off

sharply at high frequencies. Therefore, if the signal

representing ‘‘raw’’ data contains high-frequency

components then these will not be recorded. Because

the binary data to be recorded cannot be predicted it

is likely that the signal representing the data contains

a broad spectrum of frequencies ranging from very

low to very high. Consequently, the recording code

converts the frequency spectrum of the signal to be

recorded to a form that matches the response of the

recording channel.

An important function of a recording code is to

enable the regeneration of a timebase for effective

re-timing of the signal during playback. There will

be differences between the speed of the disk during

record and playback. It is essential, therefore, to

have a timebase signal that is accurately synchro-

nized to the rate at which data are read from the

disk. In effect, the recording code combines the data

to be recorded with a clock signal on recording. At

replay the clock signal is extracted and used to con-

trol a phase-locked-loop circuit that provides the

timebase.

For a given channel bandwidth the correct choice

of code can increase storage density above that of an

uncoded system. A common coding technique is

‘‘non return to zero immediate’’ (NRZI): binary one

is represented as a signal-level transition and zero as

no transition. However, there is a limit to how close

transitions can be packed together in an attempt to

increase storage density. Too close and their mutual

proximity begins to affect the ability of the detection

scheme to resolve them. The recording code intro-

duces constraints that define the separation of tran-

sitions. Consequently, for a given track length, a

greater number of code bits can be stored compared

to data bits. Although it takes more code bits to rep-

resent a given number of data bits, i.e., the code rate

is less than one, the result is a higher data-recording

density.

1. Bandwidth

The upper cut-off frequency of an optical-disk

channel is a function of the laser wavelength (l),

the track velocity (v) and the numerical aperture

(NA) and is given by 2NAv/l, (Heemskerk and Im-

mink 1982). Since the laser-spot diameter (D), is

equal to 0.5 l/NA (Bouwhuis et al. 1985) the cut-off

frequency becomes v/D. The number of bits that can

be stored on a disk depends on the size of the laser-

spot and is approximately equal to nA/D

2

, where A is

the area of the disk and n is the number of bits

that can be resolved within the spot. This latter var-

iable can be maximized through proper selection of

recording code.

Whilst, in principle, the channel response extends

down to d.c. it is prudent to limit its response at the

lower frequencies. This minimizes the adverse effect

that the low-frequency power components in the re-

played signal may have on the laser servo system.

Also, to reduce the effect of disk-surface blemishes,

which can detrimentally affect the replay signal, it is

necessary to employ a high-pass filter in the replay

channel that removes the lower frequencies. Other

considerations are the use of transformers, which do

not pass d.c. levels, in the replay channel.

2. d, k Constraint

One function of the code is to ensure that there are

never long periods of time during which there are no

transitions or that transitions do not occur too close

together. These codes are classed as run-length lim-

ited (RLL).

The minimum distance between two transitions is

the d constraint, whilst maximum distance is k. The d

and k values determine the performance of the code.

Ideally d should be low to permit high-density re-

cording but, given a finite laser-spot size, d cannot be

so low that it cannot be resolved. Also, intersymbol

interference (ISI) and inter-track cross-talk increase

with reducing d. The constraint value k cannot be too

large since frequent changes in the replayed signal are

necessary to synchronize a timebase that re-times the

replayed data.

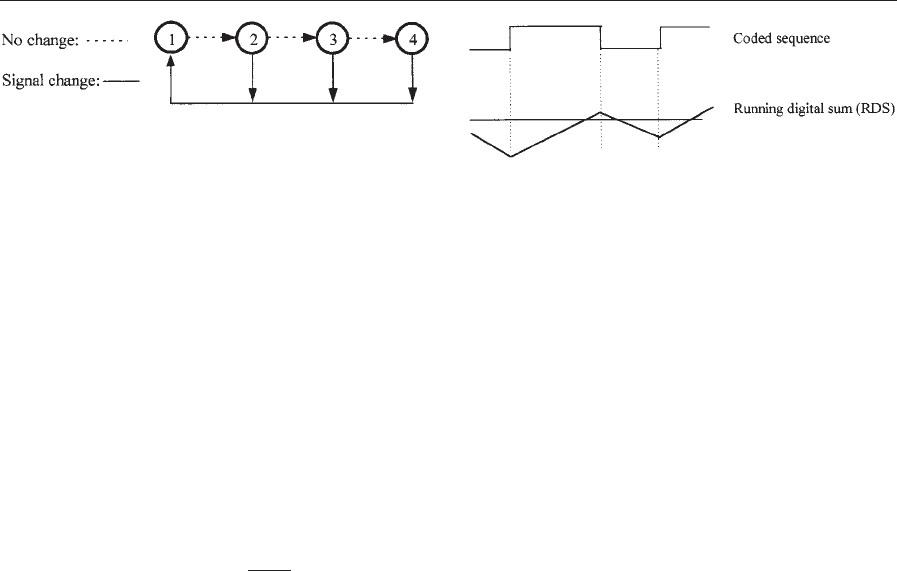

The d,k constraints of a code can be represented by

a finite-state transition diagram (FSTD) (Shannon

1948; Franaszek 1970). Figure 1 is an FSTD for a

code with constraint 1,3. The dotted paths in the di-

agram represent no level change in the code; solid

lines represent a level change, either zero to one or

one to zero. In moving from one state to another it

is seen that there must be at least one zero and a

maximum of three zeros between two changes.

O

1005

3. Channel Capa city

The maximum rate, R, at which information can be

transmitted reliably through a channel is limited by

the channel capacity C. The capacity of a channel

perturbed by white noise is given by Shannon (1948):

C ¼ Wlogð1 þ P=NÞbits s

1

ð1Þ

Where W is bandwidth and P /N is signal-to-noise

ratio. For RoC, information may be transmitted at

an arbitrarily low error rate. The actual error rate for

high R is governed by the quality of the channel and

the ingenuity of the coding scheme employed.

Shannon also defined capacity for a discrete noise-

less channel in units of user bits per channel bit

(Shannon 1948):

C ¼ lim

T-N

log

2

NðT Þ

T

ð2Þ

where N(T) is the number of allowed signals of

duration T. This reduces to log

2

l where l is the

largest root of the equation l

k þ1

l

kd

x þ1 ¼0

and d and k are the constraint parameters of the code

defined above. The equation is derived from a con-

sideration of the finite-state-timing diagram (FSTD)

of the code and its associated state transition matrix

(Siegel 1985, Immink et al. 1998).

In a recording code, m data bits are mapped into

n code bits to give a code with rate R ¼m/n, where

m/np1. The maximum theoretical code rate is known

as the capacity of the code. The efficiency of a code is

usually measured in terms of how near to C the actual

rate is.

4. Code Spectra/Equalization

Data to be recorded will be derived from a number

of diverse sources and, as such, cannot be predicted.

The various patterns of bits that are likely can be

simulated, however, using a pseudorandom binary

sequence (PRBS). If the PRBS is long it will contain

virtually all the binary combinations that the record-

ing system is likely to encounter. Assuming such a

random sequence of data, the frequency spectrum of

the ensuing coded sequence is useful in assessing code

performance. Since the optical channel response falls

off rapidly at high frequency, the high-frequency

components of a code’s spectrum should be low.

Also, the low-frequency components should have low

amplitude with a null at d.c.

Some codes are not absolutely d.c.-free: there may

be a slight dc component that will vary with the se-

quence of the signal being recorded. A measure of the

d.c.-content in the coded signal is the running digital

sum (RDS). The RDS is the running integral of the

coded signal, assuming þ1 is integrated when the

signal is high and 1 when it is low (Fig. 2). The RDS

is effectively the arithmetic sum of the area under the

graph of the integral; this should be kept low for

efficient operation. The digital sum variation (DSV)

represents the limits of the RDS graph. The d.c. con-

tent of a code is said to be bounded provided the

DSV does not extend to infinity.

A closer match between the response of the channel

and the spectrum of the code may be achieved

through equalization. Equalization is the process of

modifying the channel’s frequency response or chang-

ing the spectral content of the signal to be recorded to

more closely match the response of the channel. Here,

the channel is taken to include the write and read

electronics. One technique is to include a filter in the

channel to shape the spectrum of the code.

5. Examples of Code

In the two-thirds rate code of Horiguchi and Morita

(1976) two data bits are represented by three code

bits. The d,k value is (1,7), which gives a code

capacity of 0.679.

The code adopted for the audio compact disk (CD)

specification (and for the mini-disk) is known as

eight-to-fourteen modulation (EFM) (Heemskerk

and Immink 1982). In EFM, eight data bits are

coded into 14 code bits. However, in order to control

the d.c. content of the code, three merging bits are

added after the coding process to produce a coded

symbol 17 bits long—hence the true rate is 8/17.

Whilst the merging bits minimize the DSV, the d,k

value of (2,10) is maintained.

An improved version of EFM, EFMPlus (Immink

1995) has been adopted for the digital versatile disk

(DVD). This has the same d,k value as EFM but

the rate is higher at 8/16. Eight data bits are coded

into codewords of 16 bits using a look-up table of

Figure 2

Running digital sum (RDS) of coded sequence.

Figure 1

Finite-state transition diagram for 1,3 d,k constraint.

1006

Optical and Magneto-optic Data Storage: Channels and Coding

codewords. Rather than using merging bits to control

d.c. content, substitute codeword sequences are avail-

able at the encoder as an alternative to the main table

of codewords. During the encoding process, code-

words are taken either from the main look-up table

or from the substitute table in order to keep the DSV

at a minimum. The reduction of one bit in the code-

word yields an improvement of 6–7% in information

density compared to the EFM code.

6. Signal Detection

The basic method of determining the binary value of

the replayed analogue signal is to employ peak de-

tection. With peak detection the replayed signal is

compared with a level threshold and a binary value

registered accordingly. This is satisfactory for low to

medium density systems but if the storage density was

to be increased, inter-symbol interference would

cause signal distortion in the replayed signal. This

distortion would severely impair the detection pro-

cess. For very high-density systems, therefore, partial

response maximum likelihood (PRML) (Siegel 1991)

is usually employed. In a PRML scheme the channel

response is tightly controlled. This tight control per-

mits the ISI-induced signal distortion to be predicted,

thus enabling the corresponding binary values to be

determined in line with the replayed signal.

With peak detection a great deal of information is

wasted once the decision process is made. A more

effective, albeit more complex, method is maximum

likelihood detection. The principle behind maximum

likelihood detection is that all possible sequences of

replayed signal are known to the detector. As each

sequence is replayed it is compared to all the known

sequences: the one with the best match is the one

most likely to be the correct one. A disadvantage is

that for a reasonably long replayed sequence the de-

tection process would take too long. Viterbi detection

(Viterbi 1967) is a maximum likelihood detection

algorithm that reduces detection time by comparing

the replayed signal sequence ‘‘on-the-fly.’’ Reserved

judgements are made on sections of the replayed sig-

nal as to the likelihood of it representing a certain bit

pattern. The decision to incorporate certain combi-

nations of bits in the detected sequence depends not

only on the current signal being decoded but also on

previous evaluations: the k constraint of the record-

ing code can be used to force decisions. The result is a

detector that gives superior performance compared to

peak detection.

7. Comments

The classical work on communications channels

by Shannon can be applied to optical recording

systems, since the latter is effectively a transmit-

now, receive-later communications system. Unlike a

communications system, however, the signal power

of a recording system cannot be increased indefinitely

in order to improve performance.

A binary-data signal comprises two related com-

ponents: amplitude and time. These must be repli-

cated faithfully on replay to reconstitute the recorded

signal: this is a function of the recording code. A

further requirement of a code is to increase storage

density. However, the dual goals of achieving high

density together with reliable timebase regeneration

are contradictory. Hence, many codes have been de-

veloped in an attempt to resolve these contradictions.

The code designer must balance the storage gains to

be delivered by a code against the need for reliable

operation and cost of implementation.

The signal that is ultimately recorded is derived

from the information data, to which has been added

data for error correction, timing, synchroniza-

tion, and sundry other purposes. There is no one

‘‘supreme’’ code with all the best characteristics:

many different recording codes are in use, each de-

signed for a specific application. No small consider-

ation is the practical implementation of a code.

The recording codes in general use are single-

dimension codes, where a serial sequence of data is

coded. In an attempt to resolve the contradictory re-

quirements of a code, two-dimensional codes have

been examined (Davey et al. 1998). These codes cap-

italize on the areal format of recorded data. Mutually

related information is encoded in two dimensions.

This information is recovered at replay to support

effective detection. This concept can be extended fur-

ther to a third dimension. Such codes may be suitable

for application to multilayer disks such as the current

DVD, which has two layers, and future generations

that may possibly have many layers.

See also: Magneto-optic Recording: Overwrite and

Associated Problems; Magneto-optic Recording:

Total Film Stack, Layer Configuration

Bibliography

Bouwhuis G, et al. 1985 Principles of Optical Disc Systems.

Hilger, Bristol, UK

Davey P J, Donnelly T, Mapps D J 1998 Two-dimensional

coding for a multi-track recording system to combat inter-

track interference. IEEE Trans. Magnetics. 34 (4), 1949–51

Franaszek P A 1970 Sequence state methods of run-length-

limited coding. IBM J. Res. Dev. 14 (4),

Heemskerk J P J, Immink K A S 1982 Compact disc: system

aspects and modulation. Philips Tech. Rev. 40 (6), 157–64

Horiguchi T, Morita K 1976 An optimisation of modulation

codes in digital recording. IEEE Trans. Magn. 12 (6), 740–2

Immink K E S Coding Techniques for Digital Recorders. Pren-

tice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Immink K A S 1995 EFMPlus: The coding format of the mul-

timedia compact disc. IEEE Trans. Consumer Electron. 41

(3), 491–7

1007

Optical and Magneto-optic Data Storage : Channels and Coding

Immink K A S, Siegel P H, Wolf J K 1998 Codes for digital

recorders. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 44 (6), 2260–99

Shannon C E 1948 A mathematical theory of communication.

Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27 (3), 379–423

Siegel P H 1985 Recording codes for digital magnetic storage.

IEEE Trans. Magn (5), 1344–9

Siegel P H 1991 Recording codes for PRML. Digest Magnetic

Recording Conf. (MRC 91), paper F-2H

Siegel P H, Wolf J K 1991 Modulation coding for information

storage. IEEE Commun. Magn. (Dec), 1344–9

Viterbi A J 1967 Error bounds for convolutional codes and an

asymptotically optimum decoding algorithm. IEEE Trans.

Inf. Th. IT-13, 260–9

Watkinson J 1990 Coding for Digital Recording. Focal Press,

London

T. Donnelly

University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK

1008

Optical and Magneto-optic Data Storage: Channels and Coding

Permanent Magnet Assemblies

Modern permanent magnets are ideally suited to

generate magnetic fields of magnitudes comparable to

their spontaneous polarization, J

s

. These fields can be

static or variable, uniform or nonuniform. They are

generated by permanent magnet structures that de-

mand no continual expenditure of energy for their

operation, and dispense with the elaborate cooling

systems required by resistive or superconducting elec-

tromagnets. Furthermore, the permanent magnet as-

semblies are compact and can offer the significant

advantage of flux confinement in the region of inter-

est. Permanent magnets are now competitive with

electromagnets for generating fields of up to about

2 T. More generally, when a high field with a rapid

spatial variation is required, they may offer the only

practicable solution.

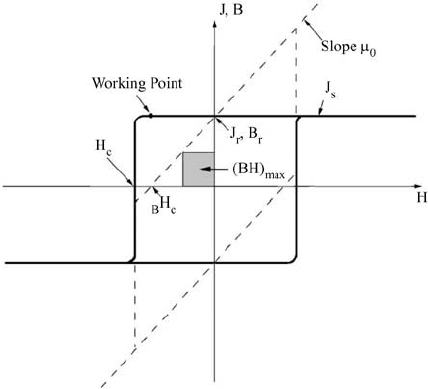

The polarization, J, of a modern hard magnet

(Skomski and Cugat 1999) deviates little from its

remanent or saturation value, J

s

, far into the second

quadrant of the hysteresis loop, before switching

at the coercive field, H

c

(see Rare Earth Magnets:

Materials, Magnets: Sintered). The plot of the polar-

ization of the magnet as a function of the magnetic

field, H, acting on it is almost rectangular in shape, as

indicated in Fig. 1. The intrinsic spontaneous polar-

ization of SrFe

12

O

19

is 0.47 T, for example, and that

of Nd

2

Fe

14

B is 1.61 T. Values of the remanent po-

larization of typical sintered magnets are given in

Table 1. They are typically 10–20% less than the

spontaneous polarization of the pure hard phase due

to imperfect crystallite alignment and the presence of

secondary phases necessary to develop coercivity.

The magnetic flux density, B, is related to the H-field

(magnetizing force) and polarization by B ¼m

0

H þJ

so that in free space, where J ¼0, the relation be-

tween B and H is simply B ¼m

0

H.

The purpose of any permanent magnet assembly is

to deliver magnetic flux into a region of space adja-

cent to the magnet known as the airgap, creating a

magnetic field, B

g

(r), in this region. Maximum energy

product, (BH)

max

, defined on the B:H loop of Fig. 1,

is equivalent to twice the energy stored in the field in

the airgap, (1/2m

0

)

R

B

2

g

dt. The energy product pro-

vides a convenient measure of the efficiency of the

magnet material for generating airgap fields. In the

case of an ideal rectangular hysteresis loop with

m

0

H

c

4J

r

/2, the maximum possible energy product,

(BH)

max

,isJ

r

2

/4m

0

.

In the structures described below, the airgap is of-

ten a cylindrical cavity surrounded by magnets. The

fields achieved in the airgap scale with, but are not

limited by the polarization of the magnets. Ideally,

the field generated is the product of a geometric con-

stant, K(r), for the structure and the remanence of the

magnet, J

r

.

KðrÞ¼B

g

ðrÞ=J

r

ð1Þ

When K41, the magnetic structure achieves flux

concentration.

Permanent magnet structures are produced by as-

sembling blocks of rare-earth magnets (see Magnets:

Sintered) or ferrite magnets (see Alnicos and Hexa-

ferrites; Ferrite Magnets: Improved Performance)in

any desired orientation. These magnets with their

wide, rectangular hysteresis loops have the property

that the field of one magnet does not significantly

perturb the magnetization of its neighbors. The mag-

net blocks behave essentially as if they are rigid and

transparent. This follows because the longitudinal

susceptibility is zero for a rectangular hysteresis loop;

the slope of the B(H) curve is m

0

, as for free space.

The transverse susceptibility, J

s

/m

0

H

a

, is only of

order 0.1, since the anisotropy field, H

a

, is much

greater than the magnetization (Table 1). Hence, for

example, the directions of magnetization of two

blocks of SmCo

5

in contact with their easy-axes per-

pendicular will deviate by less than a degree from the

easy-axes. The assumption of rigidity and transpar-

ency of the magnetization greatly simplifies the design

of magnetic circuits. Errors in the calculated airgap

Figure 1

The J(H) hysteresis loop of an ideal permanent magnet.

The corresponding B(H) loop is shown by the dotted

line. (BH)

max

is indicated by the area of the shaded

region.

P

1009