Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 9 Capital Budgeting and Risk 247

a. What proportion of each stock’s risk was market risk, and what proportion was

unique risk?

b. What is the variance of BP? What is the unique variance?

c. What is the confidence level on British Airways beta?

d. If the CAPM is correct, what is the expected return on British Airways? Assume a

risk-free interest rate of 5 percent and an expected market return of 12 percent.

e. Suppose that next year the market provides a zero return. What return would you

expect from British Airways?

5. Identify a sample of food companies on the Standard & Poor’s Market Insight website

(www

.mhhe.com/edumarketinsight

). For example, you could try Campbell Soup (CPB),

General Mills (GIS), Kellogg (K), Kraft Foods (KFT), and Sara Lee (SLE).

a. Estimate beta and R

2

for each company from the returns given on the “Monthly

Adjusted Prices” spreadsheet. The Excel functions are SLOPE and RSQ.

b. Calculate an industry beta. Here is the best procedure: First calculate the monthly

returns on an equally weighted portfolio of the stocks in your sample. Then

calculate the industry beta using these portfolio returns. How does the R

2

of this

portfolio compare to the average R

2

for the individual stocks?

c. Use the CAPM to calculate an average cost of equity (r

equity

) for the food

industry. Use current interest rates—take a look at footnote 8 in this chapter—

and a reasonable estimate of the market risk premium.

6. Look again at the companies you chose for Practice Question 5.

a. Calculate the market-value debt ratio (D/V) for each company. Note that V ⫽ D ⫹ E,

where equity value E is the product of price per share and number of shares

outstanding. E is also called “market capitalization”—see the “Monthly Valuation

Data” spreadsheet. To keep things simple, look only at long-term debt as reported on

the most recent quarterly or annual balance sheet for each company.

b. Calculate the beta for each company’s assets (

assets

), using the betas estimated in

Practice Question 5(a). Assume that

debt

⫽ .15.

c. Calculate the company cost of capital for each company. Use the debt beta of .15

to estimate the cost of debt.

d. Calculate an industry cost of capital using your answer to question 5(c). Hint:

What is the average debt ratio for your sample of food companies?

e. How would you use this food industry cost of capital in practice? Would you

recommend that an individual food company, Campbell Soup, say, should use

this industry rate to value its capital investment projects? Explain.

7. You are given the following information for Lorelei Motorwerke. Note: a300,000 means

300,000 euros.

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Long-term debt outstanding: a300,000

Current yield to maturity (r

debt

): 8%

Number of shares of common stock: 10,000

Price per share: a50

Book value per share: a25

Expected rate of return on stock (r

equity

): 15%

a. Calculate Lorelei’s company cost of capital. Ignore taxes.

b. How would r

equity

and the cost of capital change if Lorelei’s stock price fell to a25

due to declining profits? Business risk is unchanged.

8. Look again at Table 9.1. This time we will concentrate on Burlington Northern.

a. Calculate Burlington’s cost of equity from the CAPM using its own beta estimate

and the industry beta estimate. How different are your answers? Assume a risk-

free rate of 3.5 percent and a market risk premium of 8 percent.

b. Can you be confident that Burlington’s true beta is not the industry average?

c. Under what circumstances might you advise Burlington to calculate its cost of

equity based on its own beta estimate?

EXCEL

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

248 PART II Risk

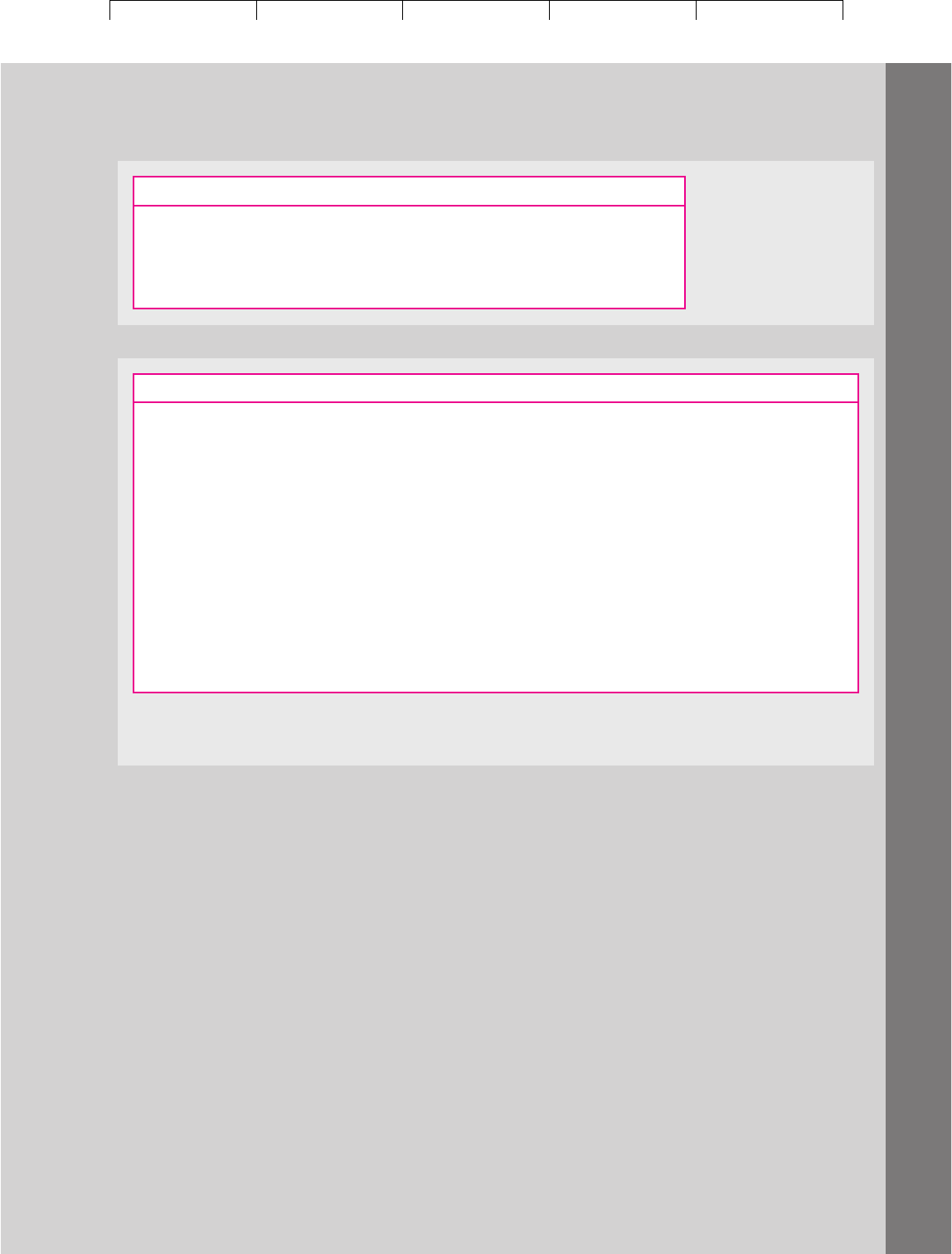

To estimate the cost of capital for each division, Amalgamated has identified the fol-

lowing three principal competitors:

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Estimated Equity Beta Debt/(Debt ⫹ Equity)

United Foods .8 .3

General Electronics 1.6 .2

Associated Chemicals 1.2 .4

Assume these betas are accurate estimates and that the CAPM is correct.

a. Assuming that the debt of these firms is risk-free, estimate the asset beta for each of

Amalgamated’s divisions.

b. Amalgamated’s ratio of debt to debt plus equity is .4. If your estimates of

divisional betas are right, what is Amalgamated’s equity beta?

c. Assume that the risk-free interest rate is 7 percent and that the expected return on

the market index is 15 percent. Estimate the cost of capital for each of

Amalgamated’s divisions.

d. How much would your estimates of each division’s cost of capital change if you

assumed that debt has a beta of .2?

10. Look at Table 9.2. What would the four countries’ betas be if the correlation coefficient

for each was 0.5? Do the calculation and explain.

11. “Investors’ home country bias is diminishing rapidly. Sooner or later most investors will

hold the world market portfolio, or a close approximation to it.” Suppose that statement

is correct. What are the implications for evaluating foreign capital investment projects?

12. Consider the beta estimates for the country indexes shown in Table 9.2. Could this infor-

mation be helpful to a U.S. company considering capital investment projects in these

countries? Would a German company find this information useful? Explain.

13. Mom and Pop Groceries has just dispatched a year’s supply of groceries to the gov-

ernment of the Central Antarctic Republic. Payment of $250,000 will be made one year

hence after the shipment arrives by snow train. Unfortunately there is a good chance of

a coup d’état, in which case the new government will not pay. Mom and Pop’s con-

troller therefore decides to discount the payment at 40 percent, rather than at the com-

pany’s 12 percent cost of capital.

a. What’s wrong with using a 40 percent rate to offset political risk?

b. How much is the $250,000 payment really worth if the odds of a coup d’état are

25 percent?

14. An oil company is drilling a series of new wells on the perimeter of a producing oil field.

About 20 percent of the new wells will be dry holes. Even if a new well strikes oil, there

is still uncertainty about the amount of oil produced: 40 percent of new wells which strike

oil produce only 1,000 barrels a day; 60 percent produce 5,000 barrels per day.

a. Forecast the annual cash revenues from a new perimeter well. Use a future oil price

of $15 per barrel.

Division Percentage of Firm Value

Food 50

Electronics 30

Chemicals 20

d. Burlington’s cost of debt was 6 percent and its debt-to-value ratio, D/V, was .40.

What was Burlington’s company cost of capital? Use the industry average beta.

9. Amalgamated Products has three operating divisions:

EXCEL

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 9 Capital Budgeting and Risk 249

b. A geologist proposes to discount the cash flows of the new wells at 30 percent to

offset the risk of dry holes. The oil company’s normal cost of capital is 10 percent.

Does this proposal make sense? Briefly explain why or why not.

15. Look back at project A in Section 9.6. Now assume that

a. Expected cash flow is $150 per year for five years.

b. The risk-free rate of interest is 5 percent.

c. The market risk premium is 6 percent.

d. The estimated beta is 1.2.

Recalculate the certainty-equivalent cash flows, and show that the ratio of these

certainty-equivalent cash flows to the risky cash flows declines by a constant pro-

portion each year.

16. A project has the following forecasted cash flows:

Cash Flows, $ Thousands

C

0

C

1

C

2

C

3

⫺100 ⫹40 ⫹60 ⫹50

The estimated project beta is 1.5. The market return r

m

is 16 percent, and the risk-free

rate r

f

is 7 percent.

a. Estimate the opportunity cost of capital and the project’s PV (using the same rate

to discount each cash flow).

b. What are the certainty-equivalent cash flows in each year?

c. What is the ratio of the certainty-equivalent cash flow to the expected cash flow in

each year?

d. Explain why this ratio declines.

17. The McGregor Whisky Company is proposing to market diet scotch. The product will first

be test-marketed for two years in southern California at an initial cost of $500,000. This test

launch is not expected to produce any profits but should reveal consumer preferences.

There is a 60 percent chance that demand will be satisfactory. In this case McGregor will

spend $5 million to launch the scotch nationwide and will receive an expected annual profit

of $700,000 in perpetuity. If demand is not satisfactory, diet scotch will be withdrawn.

Once consumer preferences are known, the product will be subject to an average de-

gree of risk, and, therefore, McGregor requires a return of 12 percent on its investment.

However, the initial test-market phase is viewed as much riskier, and McGregor de-

mands a return of 40 percent on this initial expenditure.

What is the NPV of the diet scotch project?

CHALLENGE

QUESTIONS

1. Suppose you are valuing a future stream of high-risk (high-beta) cash outflows. High

risk means a high discount rate. But the higher the discount rate, the less the present

value. This seems to say that the higher the risk of cash outflows, the less you should

worry about them! Can that be right? Should the sign of the cash flow affect the appro-

priate discount rate? Explain.

2. U.S. pharmaceutical companies have an average beta of about .8. These companies have

very little debt financing, so the asset beta is also about .8. Yet a European investor

would calculate a beta of much less than .8 relative to returns on European stock mar-

kets. (How do you explain this?) Now consider some possible implications.

a. Should German pharmaceutical companies move their R&D and production

facilities to the United States?

b. Suppose the German company uses the CAPM to calculate a cost of capital of

9 percent for investments in the United States and 12 percent at home. As a result it

plans to invest large amounts of its shareholders’ money in the United States. But its

shareholders have already demonstrated their home country bias. Should the German

company respect its shareholders’ preferences and also invest mostly at home?

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

EXCEL

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

250 PART II Risk

c. The German company can also buy shares of U.S. pharmaceutical companies.

Suppose the expected rate of return in these shares is 13 percent, reflecting their

beta of about 1.0 with respect to the U.S. market. Should the German company

demand a 13 percent rate of return on investments in the United States?

3. An oil company executive is considering investing $10 million in one or both of two

wells: Well 1 is expected to produce oil worth $3 million a year for 10 years; well 2 is ex-

pected to produce $2 million for 15 years. These are real (inflation-adjusted) cash flows.

The beta for producing wells is .9. The market risk premium is 8 percent, the nominal

risk-free interest rate is 6 percent, and expected inflation is 4 percent.

The two wells are intended to develop a previously discovered oil field. Unfortu-

nately there is still a 20 percent chance of a dry hole in each case. A dry hole means zero

cash flows and a complete loss of the $10 million investment.

Ignore taxes and make further assumptions as necessary.

a. What is the correct real discount rate for cash flows from developed wells?

b. The oil company executive proposes to add 20 percentage points to the real

discount rate to offset the risk of a dry hole. Calculate the NPV of each well with

this adjusted discount rate.

c. What do you say the NPVs of the two wells are?

d. Is there any single fudge factor that could be added to the discount rate for

developed wells that would yield the correct NPV for both wells? Explain.

4. If you have access to “Data Analysis Tools” in Excel, use the “regression” functions to

investigate the reliability of the betas estimated in Practice Questions 3 and 5 and the

industry cost of capital calculated in question 6.

a. What are the standard errors of the betas from questions 3(a) and 3(c)? Given the

standard errors, do you regard the different beta estimates obtained for each

company as signficantly different? (Perhaps the differences are just “noise.”) What

would you propose as the most reliable forecast of beta for each company?

b. How reliable are the beta estimates from question 5(a)?

c. Compare the standard error of the industry beta from question 5(b) to the standard

errors for individual-company betas. Given these standard errors, would you

change or amend your answer to question 6(e)?

MINI-CASE

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Holiport Corporation

Holiport Corporation is a diversified company with three operating divisions:

• The construction division manages infrastructure projects such as roads and bridge

construction.

• The food products division produces a range of confectionery and cookies.

• The pharmaceutical division develops and produces anti-infective drugs and animal

healthcare products.

These divisions are largely autonomous. Holiport’s small head-office financial staff is prin-

cipally concerned with applying financial controls and allocating capital between the divi-

sions. Table 9.3 summarizes each division’s assets, revenues, and profits. Holiport has always

been regarded as a conservative—some would say “stodgy”—company. Its bonds are highly

rated and yield 7 percent, only 1.5 percent more than comparable government bonds.

Holiport’s previous CFO, Sir Reginald Holiport-Bentley, retired last year after an auto-

cratic 12-year reign. He insisted on a hurdle rate of 12 percent for all capital expenditures for

all three divisions. This rate never changed, despite wide fluctuations in interest rates and

inflation. However, the new CFO, Miss Florence Holiport-Bentley-Smythe (Sir Reginald’s

niece) had brought a breath of fresh air into the head office. She was determined to set dif-

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 9 Capital Budgeting and Risk 251

ferent costs of capital for each division. So when Henry Rodriguez returned from vacation,

he was not surprised to find in his in-tray a memo from the new CFO. He was asked to de-

termine how the company should establish divisional costs of capital and to provide esti-

mates for the three divisions and for the company as a whole.

The new CFO’s memo warned him not to confine himself to just one cookbook method,

but to examine alternative estimates of the cost of capital. He also remembered a heated dis-

cussion between Florence and her uncle. Sir Reginald departed insisting that the only good

forecast of the market risk premium was a long-run historical average; Florence argued

strongly that alert, modern investors required much lower returns. Henry failed to see what

“alert” and “modern” had to do with a market risk premium. Nevertheless, Henry decided

that his report should address this question head on.

Henry started by identifying the three closest competitors to Holiport’s divisions.

Burchetts Green is a construction company, Unifoods produces candy, and Pharmichem is

Holiport’s main competitor in the animal healthcare business. Henry jotted down the sum-

mary data in Table 9.4 and poured himself a large cup of black coffee.

Questions

1. Help Henry Rogriguez by writing a memo to the CFO on Holiport’s cost of capital. Your

memo should (a) outline the merits of alternative methods for estimating the cost of

capital, (b) explain your views on the market risk premium, and (c) provide an estimate

of the cost of capital for each of Holiport’s divisions.

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Holiport Burchetts Green Unifoods Pharmichem

Cash and marketable securities 374 66 21 388

Other current assets 1596 408 377 1276

Fixed assets 2436 526 868 2077

Total assets 4406 1000 1266 3740

Short-term debt 340 66 81 21

Other current liabilities 1042 358 225 1273

Long-term debt 601 64 396 178

Equity 2423 512 564 2269

Total liabilities and equity 4406 1000 1266 3740

Number of shares, millions 1520 76 142 1299

Share price (

£) 8.00 9.1 25.4 28.25

Dividend yield (%) 2.0 1.9 1.4 0.6

P/E ratio 31.1 14.5 27.6 46.6

Estimated  of stock 1.03 .80 1.15 .96

TABLE 9.4

Summary financial data for comparable companies (figures in £ millions, except as noted).

Construction Food Products Pharmaceuticals

Net working capital 47 373 168

Fixed assets 792 561 1083

Total net assets 839 934 1251

Revenues 1814 917 1271

Net profits 15 149 227

TABLE 9.3

Summary financial data

for Holiport Corporation’s

three operating divisions

(figures in £ millions).

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Robert Shiller’s home page includes long-term

data on U.S. stock and bill returns:

www

.aida.econ.yale.edu

Equity betas for individual stocks are found on

Yahoo. (Or you can download the stock prices

from Yahoo and calculate your own measures):

www

.finance.yahoo.com

Aswath Damodoran’s home page contains good

long-term data on U.S. equities and average eq-

uity and asset betas for U.S. industries:

www

.equity.stern.nyu.edu/⬃adamodar/

New

Home Page

Another useful site is Campbell Harvey’s home

page. It contains data on past stock returns and

risk, and software to calculate mean-variance ef-

ficient frontiers:

www

.duke.edu/

⬃charvey

Data on the Fama-French factors are published

on Ken French’s website:

www

.mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/

faculty/ken.fr

ench

ValuePro provides software and data for estimat-

ing company cost of capital:

www

.valuepro.net

For a collection of recent articles on the cost of

capital see:

www

.ibbotson.com

# 39135 C t MH/BR A B l /M P N 252

RELATED WEBSITES

PART TWO

RELATED

WEBSITES

_ _

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER TEN

254

A PROJECT IS NOT

A BLACK BOX

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

A BLACK BOX is something that we accept and use but do not understand. For most of us a computer

is a black box. We may know what it is supposed to do, but we do not understand how it works and,

if something breaks, we cannot fix it.

We have been treating capital projects as black boxes. In other words, we have talked as if man-

agers are handed unbiased cash-flow forecasts and their only task is to assess risk, choose the right

discount rate, and crank out net present value. Actual financial managers won’t rest until they un-

derstand what makes the project tick and what could go wrong with it. Remember Murphy’s law, “If

anything can go wrong, it will,” and O’Reilly’s corollary, “at the worst possible time.”

Even if the project’s risk is wholly diversifiable, you still need to understand why the venture could

fail. Once you know that, you can decide whether it is worth trying to resolve the uncertainty. Maybe

further expenditure on market research would clear up those doubts about acceptance by con-

sumers, maybe another drill hole would give you a better idea of the size of the ore body, and maybe

some further work on the test bed would confirm the durability of those welds. If the project really

has a negative NPV, the sooner you can identify it, the better. And even if you decide that it is worth

going ahead on the basis of present information, you do not want to be caught by surprise if things

subsequently go wrong. You want to know the danger signals and the actions you might take.

We will show you how to use sensitivity analysis, break-even analysis, and Monte Carlo simulation

to identify crucial assumptions and to explore what can go wrong. There is no magic in these tech-

niques, just computer-assisted common sense. You don’t need a license to use them.

Discounted-cash-flow analysis commonly assumes that companies hold assets passively, and it ig-

nores the opportunities to expand the project if it is successful or to bail out if it is not. However, wise

managers value these opportunities. They look for ways to capitalize on success and to reduce the costs

of failure, and they are prepared to pay up for projects that give them this flexibility. Opportunities to

modify projects as the future unfolds are known as real options. We describe several important real op-

tions, and we show how to use decision trees to set out these options’ attributes and implications.

255

Uncertainty means that more things can happen than will happen. Whenever

you are confronted with a cash-flow forecast, you should try to discover what

else can happen.

Put yourself in the well-heeled shoes of the treasurer of the Otobai Company in

Osaka, Japan. You are considering the introduction of an electrically powered mo-

tor scooter for city use. Your staff members have prepared the cash-flow forecasts

shown in Table 10.1. Since NPV is positive at the 10 percent opportunity cost of cap-

ital, it appears to be worth going ahead.

Before you decide, you want to delve into these forecasts and identify the key

variables that determine whether the project succeeds or fails. It turns out that the

marketing department has estimated revenue as follows:

.1 1 million 100,000 scooters

Unit sales new product’s share of market size of scooter market

NPV 15

a

10

t1

3

11.102

t

¥3.43 billion

10.1 SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

The production department has estimated variable costs per unit as ¥300,000. Since

projected volume is 100,000 scooters per year, total variable cost is ¥30 billion. Fixed

costs are ¥3 billion per year. The initial investment can be depreciated on a straight-

line basis over the 10-year period, and profits are taxed at a rate of 50 percent.

These seem to be the important things you need to know, but look out for

unidentified variables. Perhaps there are patent problems, or perhaps you will

need to invest in service stations that will recharge the scooter batteries. The

greatest dangers often lie in these unknown unknowns, or “unk-unks,” as scien-

tists call them.

Having found no unk-unks (no doubt you’ll find them later), you conduct a sen-

sitivity analysis with respect to market size, market share, and so on. To do this,

the marketing and production staffs are asked to give optimistic and pessimistic

estimates for the underlying variables. These are set out in the left-hand columns

of Table 10.2. The right-hand side shows what happens to the project’s net present

value if the variables are set one at a time to their optimistic and pessimistic values.

Your project appears to be by no means a sure thing. The most dangerous variables

appear to be market share and unit variable cost. If market share is only .04 (and

all other variables are as expected), then the project has an NPV of ¥10.4 billion.

If unit variable cost is ¥360,000 (and all other variables are as expected), then the

project has an NPV of ¥15 billion.

Value of Information

Now you can check whether an investment of time or money could resolve some

of the uncertainty before your company parts with the ¥15 billion investment. Sup-

pose that the pessimistic value for unit variable cost partly reflects the production

department’s worry that a particular machine will not work as designed and that

the operation will have to be performed by other methods at an extra cost of

¥20,000 per unit. The chance that this will occur is only 1 in 10. But, if it does occur,

the extra ¥20,000 unit cost will reduce after-tax cash flow by

100,000 20,000 .50 ¥1 billion

Unit sales additional unit cost 11 tax rate2

100,000 375,000 ¥37.5 billion

Revenue unit sales price per unit

256 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

Year 0 Years 1–10

Investment 15

1. Revenue 37.5

2. Variable cost 30

3. Fixed cost 3

4. Depreciation 1.5

5. Pretax profit (1 2 3 4) 3

6. Tax 1.5

7. Net profit (5 6) 1.5

8. Operating cash flow (4 7) 3

Net cash flow 15 3

TABLE 10.1

Preliminary cash-flow forecasts for Otobai’s

electric scooter project (figures in ¥ billions).

Assumptions:

1. Investment is depreciated over 10 years

straight-line.

2. Income is taxed at a rate of 50 percent.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

It would reduce the NPV of your project by

putting the NPV of the scooter project underwater at 3.43 6.14 ¥2.71 billion.

Suppose further that a ¥10 million pretest of the machine will reveal whether it

will work or not and allow you to clear up the problem. It clearly pays to invest

¥10 million to avoid a 10 percent probability of a ¥6.14 billion fall in NPV. You are

ahead by 10 .10 6,140 ¥604 million.

On the other hand, the value of additional information about market size is small.

Because the project is acceptable even under pessimistic assumptions about market

size, you are unlikely to be in trouble if you have misestimated that variable.

Limits to Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis boils down to expressing cash flows in terms of key project vari-

ables and then calculating the consequences of misestimating the variables. It forces

the manager to identify the underlying variables, indicates where additional informa-

tion would be most useful, and helps to expose confused or inappropriate forecasts.

One drawback to sensitivity analysis is that it always gives somewhat ambigu-

ous results. For example, what exactly does optimistic or pessimistic mean? The mar-

keting department may be interpreting the terms in a different way from the pro-

duction department. Ten years from now, after hundreds of projects, hindsight

may show that the marketing department’s pessimistic limit was exceeded twice

as often as the production department’s; but what you may discover 10 years hence

is no help now. One solution is to ask the two departments for a complete descrip-

tion of the various odds. However, it is far from easy to extract a forecaster’s sub-

jective notion of the complete probability distribution of possible outcomes.

1

Another problem with sensitivity analysis is that the underlying variables are

likely to be interrelated. What sense does it make to look at the effect in isolation

of an increase in market size? If market size exceeds expectations, it is likely that

a

10

t1

1

11.102

t

¥6.14 billion,

CHAPTER 10

A Project Is Not a Black Box 257

Range NPV, ¥ Billions

Variable Pessimistic Expected Optimistic Pessimistic Expected Optimistic

Market size .9 million 1 million 1.1 million 1.1 3.4 5.7

Market share .04 .1 .16 10.4 3.4 17.3

Unit price ¥350,000 ¥375,000 ¥380,000 4.2 3.4 5.0

Unit variable cost ¥360,000 ¥300,000 ¥275,000 15.0 3.4 11.1

Fixed cost ¥4 billion ¥3 billion ¥2 billion .4 3.4 6.5

TABLE 10.2

To undertake a sensitivity analysis of the electric scooter project, we set each variable in turn at its most pessimistic or

optimistic value and recalculate the NPV of the project.

1

If you doubt this, try some simple experiments. Ask the person who repairs your television to state a

numerical probability that your set will work for at least one more year. Or construct your own subjec-

tive probability distribution of the number of telephone calls you will receive next week. That ought to

be easy. Try it.