Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

only 1 or 2 may ever get to market. The 1 or 2 that are marketed have to

generate enough cash flow to make up for the 9,999 or 9,998 that fail.)

2. Market success. FDA approval does not guarantee that a drug will sell. A

competitor may be there first with a similar (or better) drug. The company

may or may not be able to sell the drug worldwide. Selling prices and

marketing costs are unknown.

Imagine that you are standing at the top left of Figure 10.5. A proposed research

program will investigate a promising class of compounds. Could you write down

the expected cash inflows and outflows of the program up to 25 or 30 years in the

future? We suggest that no mortal could do so without a model to help; simulation

may provide the answer.

13

Simulation may sound like a panacea for the world’s ills, but, as usual, you pay

for what you get. Sometimes you pay for more than you get. It is not just a matter

of the time and money spent in building the model. It is extremely difficult to esti-

mate interrelationships between variables and the underlying probability distri-

butions, even when you are trying to be honest.

14

But in capital budgeting, fore-

casters are seldom completely impartial and the probability distributions on which

simulations are based can be highly biased.

In practice, a simulation that attempts to be realistic will also be complex. There-

fore the decision maker may delegate the task of constructing the model to man-

agement scientists or consultants. The danger here is that, even if the builders un-

derstand their creation, the decision maker cannot and therefore does not rely on

it. This is a common but ironic experience: The model that was intended to open

up black boxes ends up creating another one.

268 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

13

N. A. Nichols, “Scientific Management at Merck: An Interview with CFO Judy Lewent,” Harvard Busi-

ness Review 72 (January–February 1994), p. 91.

14

These difficulties are less severe for the pharmaceutical industry than for most other industries.

Pharmaceutical companies have accumulated a great deal of information on the probabilities of scien-

tific and clinical success and on the time and money required for clinical testing and FDA approval.

15

Some simulation models do recognize the possibility of changing policy. For example, when a phar-

maceutical company uses simulation to analyze its R&D decisions, it allows for the possibility that the

company can abandon the development at each phase.

10.3 REAL OPTIONS AND DECISION TREES

If financial managers treat projects as black boxes, they may be tempted to think only

of the first accept–reject decision and to ignore the subsequent investment decisions

that may be tied to it. But if subsequent investment decisions depend on those made

today, then today’s decision may depend on what you plan to do tomorrow.

When you use discounted cash flow (DCF) to value a project, you implicitly as-

sume that the firm will hold the assets passively. But managers are not paid to be

dummies. After they have invested in a new project, they do not simply sit back and

watch the future unfold. If things go well, the project may be expanded; if they go

badly, the project may be cut back or abandoned altogether. Projects that can easily

be modified in these ways are more valuable than those that don’t provide such flex-

ibility. The more uncertain the outlook, the more valuable this flexibility becomes.

That sounds obvious, but notice that sensitivity analysis and Monte Carlo

simulation do not recognize the opportunity to modify projects.

15

For example,

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

think back to the Otobai electric scooter project. In real life, if things go wrong

with the project, Otobai would abandon to cut its losses. If so, the worst out-

comes would not be as devastating as our sensitivity analysis and simulation

suggested.

Options to modify projects are known as real options. Managers may not al-

ways use the term real option to describe these opportunities; for example, they

may refer to “intangible advantages” of easy-to-modify projects. But when they

review major investment proposals, these option intangibles are often the key to

their decisions.

The Option to Expand

In 2000 FedEx placed an order for 10 Airbus A380 superjumbo transport planes for

delivery in the years 2008–2011. Each flight of an A380 freighter will be capable of

making a 200,000 pound dent in the massive volume of goods that FedEx carries

each day, so the decision could have a huge impact on FedEx’s worldwide busi-

ness. If FedEx’s long-haul airfreight business continues to expand and the super-

jumbo is efficient and reliable, the company will need more superjumbos. But it

cannot be sure they will be needed.

Rather than placing further firm orders in 2000, FedEx has secured a place in the

Airbus production line by acquiring options to buy a “substantial number” of ad-

ditional aircraft at a predetermined price. These options do not commit the com-

pany to expand but give it the flexibility to do so.

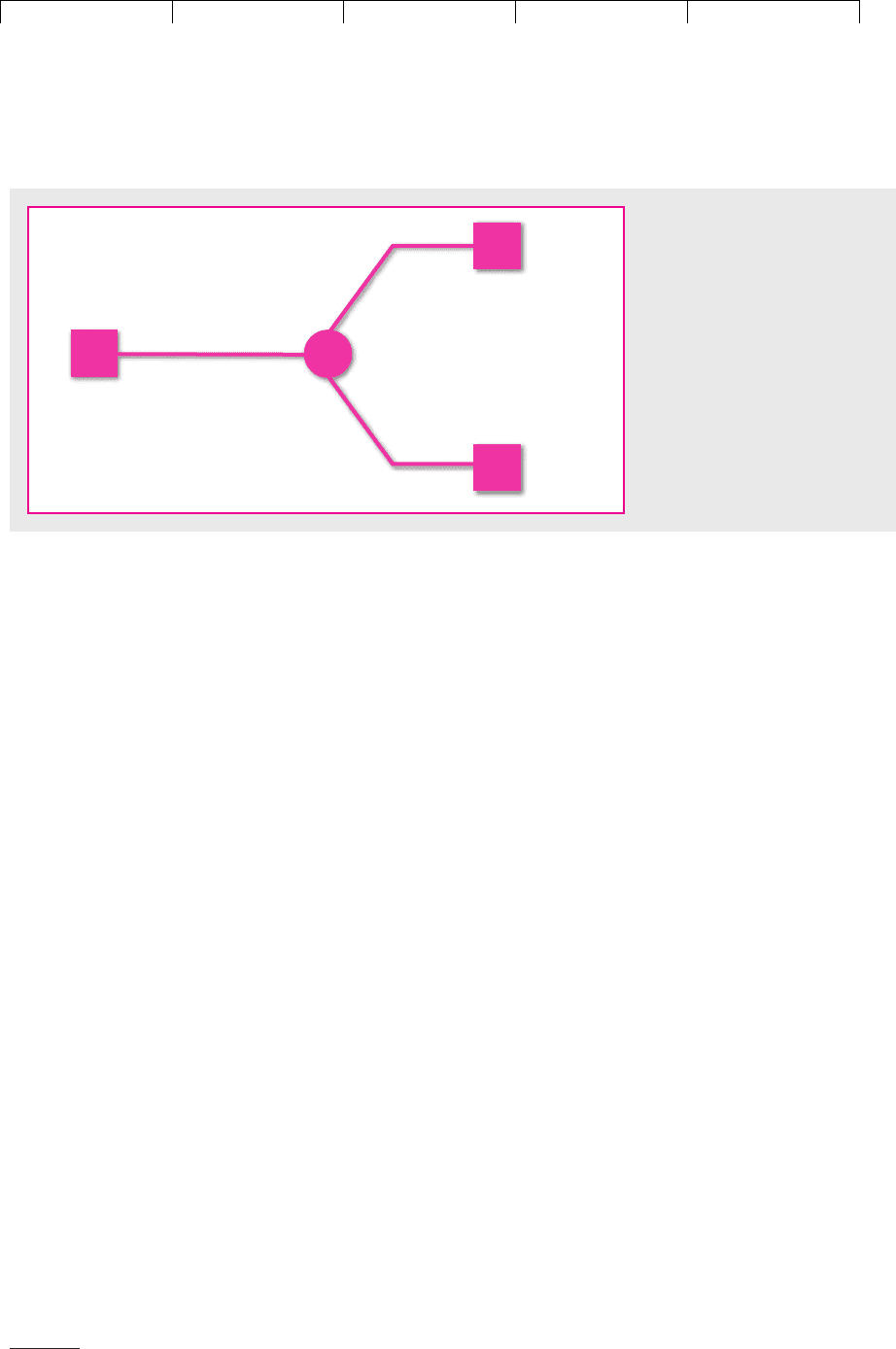

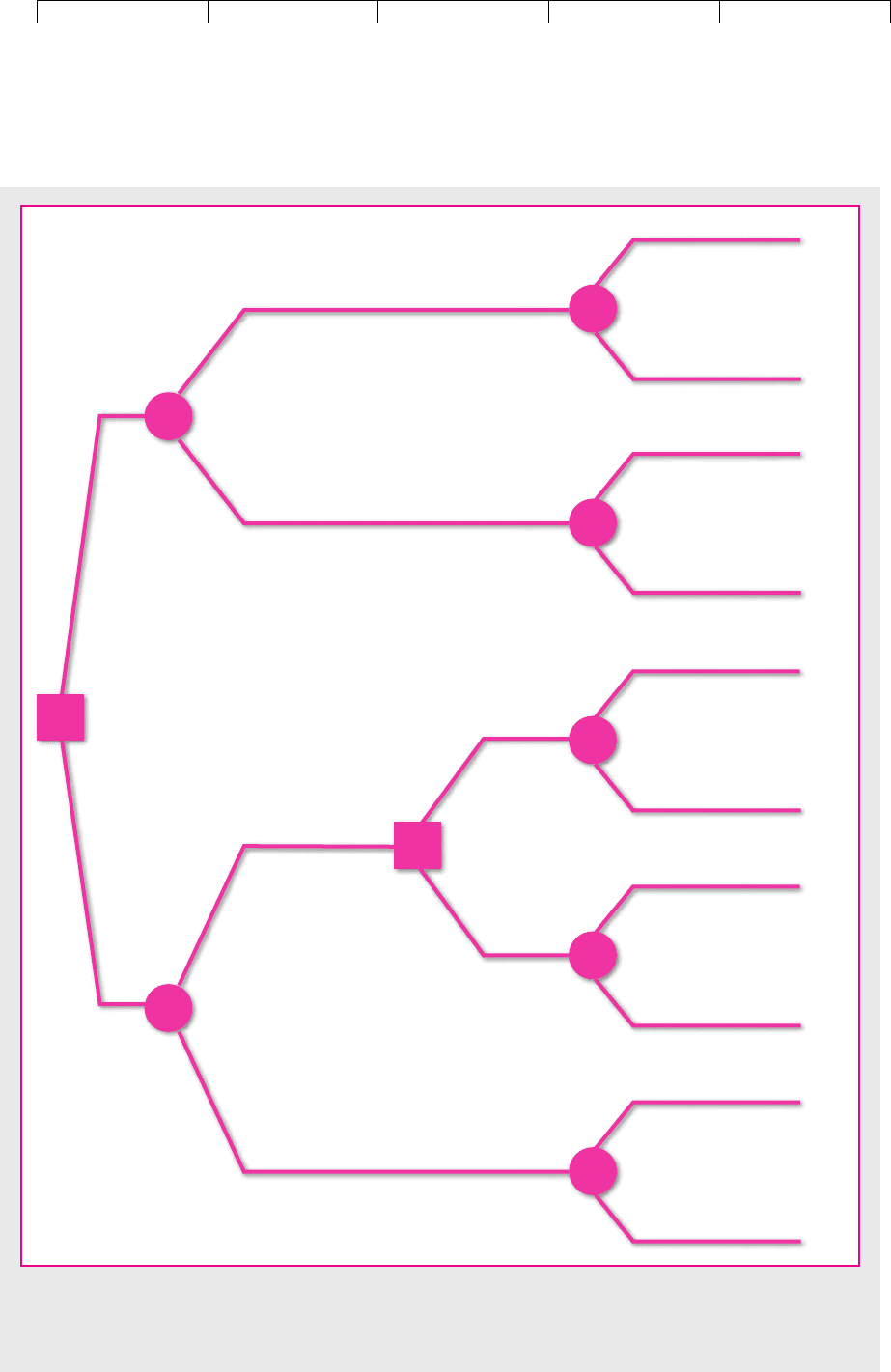

Figure 10.6 displays FedEx’s expansion option as a simple decision tree. You

can think of it as a game between FedEx and fate. Each square represents an action

or decision by the company. Each circle represents an outcome revealed by fate. In

this case there is only one outcome in 2007,

16

when fate reveals the airfreight de-

mand and FedEx’s capacity needs. FedEx then decides whether to exercise its op-

tions and buy additional A380s. Here the future decision is easy: Buy the airplanes

only if demand is high and the company can operate them profitably. If demand is

low, FedEx walks away and leaves Airbus with the problem of selling the planes

that were reserved for FedEx to some other customer.

CHAPTER 10

A Project Is Not a Black Box 269

High

demand

2007: Observe

demand for

airfreight

2000: Acquire

delivery option

in 2008–2011

Exercise

delivery

option

Don't take

delivery

Low

demand

FIGURE 10.6

FedEx’s expansion option

expressed as a simple

decision tree.

16

We assume that FedEx can wait until 2007 to decide whether to acquire the additional planes.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

You can probably think of many other investments that take on added value be-

cause of the further options they provide. For example

• When launching a new product, companies often start with a pilot program to

iron out possible design problems and to test the market. The company can

evaluate the pilot and then decide whether to expand to full-scale production.

• When designing a factory, it can make sense to provide extra land or floor

space to reduce the future cost of a second production line.

• When building a four-lane highway, it may pay to build six-lane bridges so

that the road can be converted later to six lanes if traffic volumes turn out to

be higher than expected.

Such options to expand do not show up in the assets that the company lists in its

balance sheet, but investors are very aware of their existence. If a company has

valuable real options that can allow it to invest in new profitable projects, its mar-

ket value will be higher than the value of its physical assets now in place.

In Chapter 4 we showed how the present value of growth opportunities (PVGO)

contributes to the value of a company’s common stock. PVGO equals the fore-

casted total NPV of future investments. But it’s better to think of PVGO as the

value of the firm’s options to invest and expand. The firm is not obliged to grow. It

can invest more if the number of positive-NPV projects turns out high or slow

down if that number turns out low. The flexibility to adapt investment to future op-

portunities is one of the factors that makes PVGO so valuable.

The Option to Abandon

If the option to expand has value, what about the decision to bail out? Projects

don’t just go on until assets expire of old age. The decision to terminate a project

is usually taken by management, not by nature. Once the project is no longer

profitable, the company will cut its losses and exercise its option to abandon the

project.

17

Some assets are easier to bail out of than others. Tangible assets are usually eas-

ier to sell than intangible ones. It helps to have active secondhand markets, which

really exist only for standardized items. Real estate, airplanes, trucks, and certain

machine tools are likely to be relatively easy to sell. On the other hand, the knowl-

edge accumulated by a software company’s research and development program is

a specialized intangible asset and probably would not have significant abandon-

ment value. (Some assets, such as old mattresses, even have negative abandonment

value; you have to pay to get rid of them. It is costly to decommission nuclear

power plants or to reclaim land that has been strip-mined.)

Example. Managers should recognize the option to abandon when they make

the initial investment in a new project or venture. For example, suppose you

must choose between two technologies for production of a Wankel-engine out-

board motor.

1. Technology A uses computer-controlled machinery custom-designed to

produce the complex shapes required for Wankel engines in high volumes

and at low cost. But if the Wankel outboard doesn’t sell, this equipment will

be worthless.

270 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

17

The abandonment option was first analyzed by A. A. Robichek and J. C. Van Horne, “Abandonment

Value in Capital Budgeting,” Journal of Finance 22 (December 1967), pp. 577–590.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

2. Technology B uses standard machine tools. Labour costs are much higher,

but the machinery can be sold for $10 million if the engine doesn’t sell.

Technology A looks better in a DCF analysis of the new product because it was de-

signed to have the lowest possible cost at the planned production volume. Yet you

can sense the advantage of technology B’s flexibility if you are unsure about

whether the new outboard will sink or swim in the marketplace.

We can make the value of this flexibility concrete by expressing it as a real op-

tion. Just for simplicity, assume that the initial capital outlays for technologies A

and B are the same. Technology A, with its low-cost customized machinery, will

provide a payoff of $18.5 million if the outboard is popular with boat owners

and $8.5 million if it is not. Think of these payoffs as the project’s cash flow in

its first year of production plus the present value of all subsequent cash flows.

The corresponding payoffs to technology B are $18 million and $8 million.

CHAPTER 10

A Project Is Not a Black Box 271

Payoffs from Producing

Outboard ($ millions)

Technology A Technology B

Buoyant demand $18.5 $18

Sluggish demand 8.5 8

If you are obliged to continue in production regardless of how unprofitable the project

turns out to be, then technology A is clearly the superior choice. But remember

that at year-end you can bail out of technology B for $10 million. If the outboard

is not a success in the market, you are better off selling the plant and equipment

for $10 million than continuing with a project that has a present value of only

$8 million.

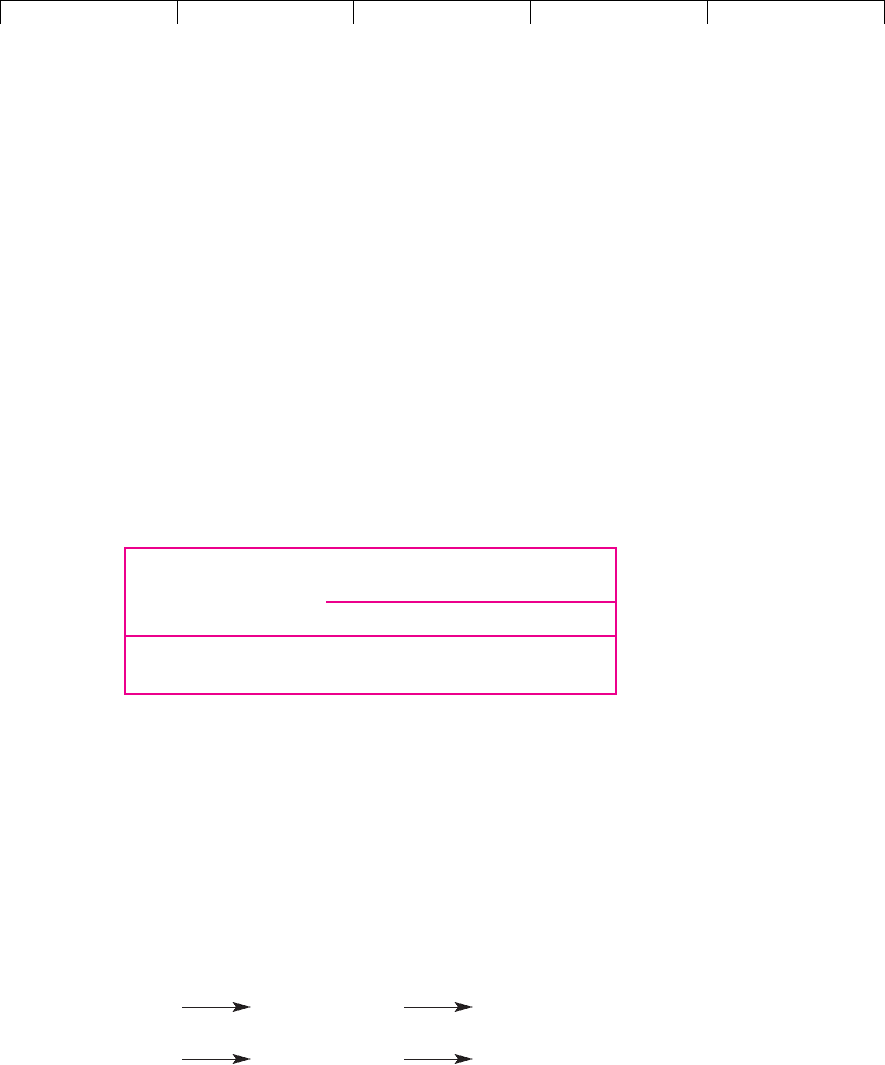

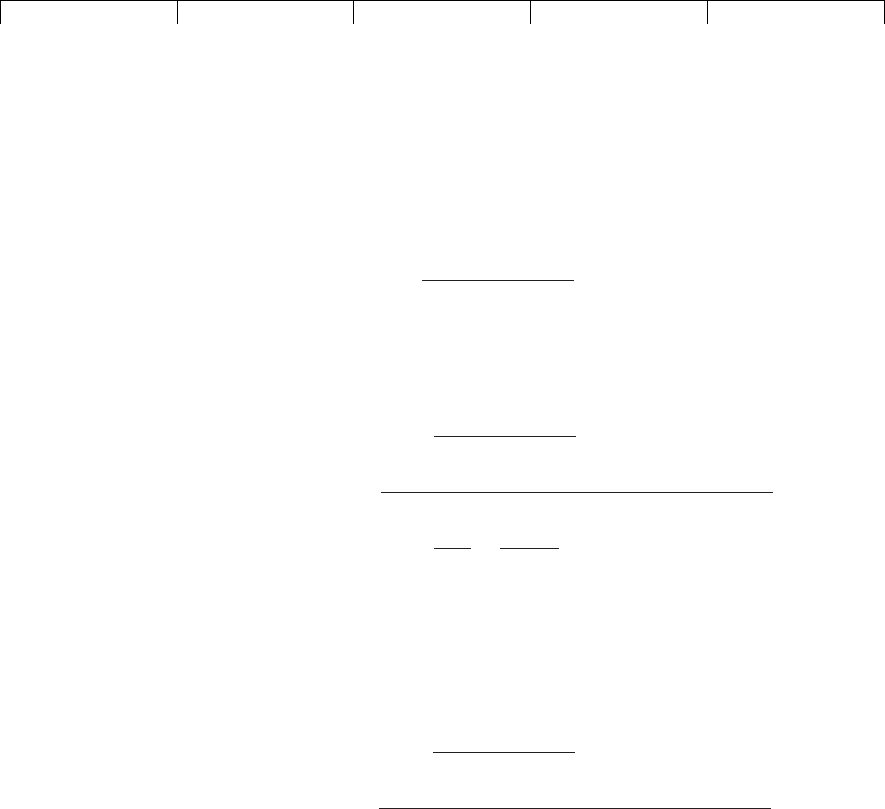

Figure 10.7 summarizes this example as a decision tree. The abandonment op-

tion occurs at the right-hand boxes for Technology B. The decisions are obvious:

continue if demand is buoyant, abandon otherwise. Thus the payoffs to Technol-

ogy B are:

Buoyant continue own business

demand production worth $18 million

Sluggish exercise option receive

demand to sell assets $10 million

Technology B provides an insurance policy: If the outboard’s sales are disap-

pointing, you can abandon the project and recover $10 million. You can think of

this abandonment option as an option to sell the assets for $10 million. The total

value of the project using technology B is its DCF value, assuming that the com-

pany does not abandon, plus the value of the abandonment option. When you

value this option, you are placing a value on flexibility.

Two Other Real Options

These are not the only real options. For example, companies with positive-NPV

projects are not obliged to undertake them right away. If the outlook is uncertain,

you may be able to avoid a costly mistake by waiting a bit. Such options to post-

pone investment are called timing options.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

When companies undertake new investments, they generally think about the

possibility that at a later stage they may wish to modify the project. After all, to-

day everybody may be demanding round pegs, but, who knows, tomorrow

square ones could be all the rage. In that case you need a plant that provides the

flexibility to produce a variety of peg shapes. In just the same way, it may be

worth paying up front for the flexibility to vary the inputs. For example, in Chap-

ter 22 we will describe how electric utilities often build in the option to switch be-

272 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

Technology A

Demand

revealed

Demand

revealed

Technology B

Buoyant

Sluggish

$18.5 million

$8.5 million

$18 million

$10 million

$8 million

$10 million

Abandon

Continue

Continue

Abandon

Buoyant

Sluggish

FIGURE 10.7

Decision tree for the

Wankel outboard motor

project. Technology B

allows the firm to

abandon the project and

recover $10 million if

demand is sluggish.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

tween burning oil to burning natural gas. We refer to these opportunities as pro-

duction options.

More on Decision Trees

We will return to all these real options in Chapter 22, after we have covered the the-

ory of option valuation in Chapters 20 and 21. But we will close this chapter with

a closer look at decision trees.

Decision trees are commonly used to describe the real options imbedded in cap-

ital investment projects. But decision trees were used in the analysis of projects

years before real options were first explicitly identified.

18

Decision trees can help

to understand project risk and how future decisions will affect project cash flows.

Even if you never learn or use option valuation theory, decision trees belong in

your financial toolkit.

The best way to appreciate how decision trees can be used in project analysis is

to work through a detailed example.

An Example: Magna Charter

Magna Charter is a new corporation formed by Agnes Magna to provide an executive

flying service for the southeastern United States. The founder thinks there will be a

ready demand from businesses that cannot justify a full-time company plane but nev-

ertheless need one from time to time. However, the venture is not a sure thing. There

is a 40 percent chance that demand in the first year will be low. If it is low, there is a 60

percent chance that it will remain low in subsequent years. On the other hand, if the

initial demand is high, there is an 80 percent chance that it will stay high.

The immediate problem is to decide what kind of plane to buy. A turboprop

costs $550,000. A piston-engine plane costs only $250,000 but has less capacity and

customer appeal. Moreover, the piston-engine plane is an old design and likely to

depreciate rapidly. Ms. Magna thinks that next year secondhand piston aircraft

will be available for only $150,000.

That gives Ms. Magna an idea: Why not start out with one piston plane and buy

another if demand is still high? It will cost only $150,000 to expand. If demand is

low, Magna Charter can sit tight with one small, relatively inexpensive aircraft.

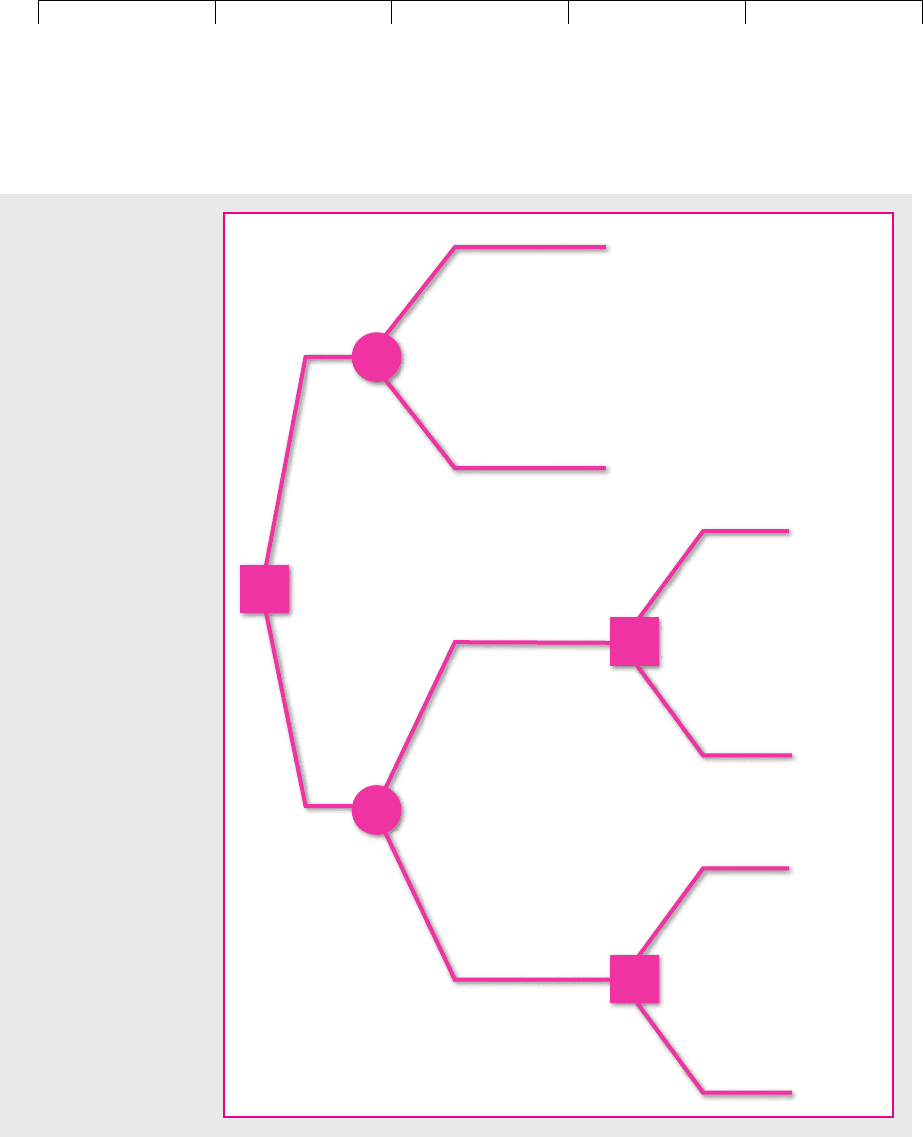

Figure 10.8 displays these choices. The square on the left marks the company’s

initial decision to purchase a turboprop for $550,000 or a piston aircraft for

$250,000. After the company has made its decision, fate decides on the first year’s

demand. You can see in parentheses the probability that demand will be high or

low, and you can see the expected cash flow for each combination of aircraft and

demand level. At the end of the year the company has a second decision to make

if it has a piston-engine aircraft: It can either expand or sit tight. This decision point

is marked by the second square. Finally fate takes over again and selects the level

of demand for year 2. Again you can see in parentheses the probability of high or

low demand. Notice that the probabilities for the second year depend on the first-

period outcomes. For example, if demand is high in the first period, then there is

an 80 percent chance that it will also be high in the second. The chance of high

CHAPTER 10

A Project Is Not a Black Box 273

18

The use of decision trees was first advocated by J. Magee in “How to Use Decision Trees in Capital In-

vestment,” Harvard Business Review 42(September–October 1964), pp. 79–96. Real options were first

identified in S. C. Myers, “Determinants of Corporate Borrowing,” Journal of Financial Economics 5

(November 1977), pp. 146–175.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

274 PART III Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

Turboprop

–$550

Piston

–$250

Low demand (.2)

High demand (.8)

High demand (.6)

$150

Low demand (.4)

$30

$220

$960

Low demand (.6)

High demand (.4)

$140

$930

Low demand (.2)

High demand (.8)

High demand (.6)

$100

Expand

–$150

Do not

expand

Low demand (.4)

$50

$100

$800

Low demand (.6)

High demand (.4)

$100

$220

Low demand (.2)

High demand (.8)

$180

$410

FIGURE 10.8

Decision tree for Magna Charter. Should it buy a turboprop or a smaller piston-engine plane? A second piston plane can

be purchased in year 1 if demand turns out to be high. (All figures are in thousands. Probabilities are in parentheses.)

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

demand in both the first and second periods is .6 .8 .48. After the parentheses

we again show the profitability of the project for each combination of aircraft and

demand level. You can interpret each of these figures as the present value at the end

of year 2 of the cash flows for that and all subsequent years.

The problem for Ms. Magna is to decide what to do today. We solve that prob-

lem by thinking first what she would do next year. This means that we start at the

right side of the tree and work backward to the beginning on the left.

The only decision that Ms. Magna needs to make next year is whether to expand

if purchase of a piston-engine plane is succeeded by high demand. If she expands,

she invests $150,000 and receives a payoff of $800,000 if demand continues to be

high and $100,000 if demand falls. So her expected payoff is

low demand)

If the opportunity cost of capital for this venture is 10 percent,

19

then the net pres-

ent value of expanding, computed as of year 1, is

If Ms. Magna does not expand, the expected payoff is

low demand)

The net present value of not expanding, computed as of year 1, is

Expansion obviously pays if market demand is high.

Now that we know what Magna Charter ought to do if faced with the expansion

decision, we can roll back to today’s decision. If the first piston-engine plane is

bought, Magna can expect to receive cash worth $550,000 in year 1 if demand is

high and cash worth $185,000 if it is low:

NPV 0

364

1.10

331, or $331,000

1.8 4102 1.2 1802364, or $364,000

1probability low demand payoff with

1Probability high demand payoff with high demand2

NPV 150

660

1.10

450, or $450,000

1.8 8002 1.2 1002660, or $660,000

1probability low demand payoff with

1Probability high demand payoff with high demand2

CHAPTER 10 A Project Is Not a Black Box 275

19

We are guilty here of assuming away one of the most difficult questions. Just as in the Vegetron mop

case in Chapter 9, the most risky part of Ms. Magna’s venture is likely to be the initial prototype proj-

ect. Perhaps we should use a lower discount rate for the second piston-engine plane than for the first.

High demand (.6)

$550,000

Invest

$250,000

Low demand (.4)

$185,000

$100,000 cash flow

plus $450,000 net

present value

$50,000 cash flow

plus net present value of

= $135,000

(.4

×

220)

+

(.6

×

100)

1.10

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

The net present value of the investment in the piston-engine plane is therefore

$117,000:

If Magna buys the turboprop, there are no future decisions to analyze, and

so there is no need to roll back. We just calculate expected cash flows and

discount:

Thus the investment in the piston-engine plane has an NPV of $117,000; the in-

vestment in the turboprop has an NPV of $96,000. The piston-engine plane is the

better bet. Note, however, that the choice would be different if we forgot to take ac-

count of the option to expand. In that case the NPV of the piston-engine plane

would drop from $117,000 to $52,000:

The value of the option to expand is, therefore,

The decision tree in Figure 10.8 recognizes that, if Ms. Magna buys one piston-

engine plane, she is not stuck with that decision. She has the option to expand by

buying an additional plane if demand turns out to be unexpectedly high. But Fig-

ure 10.8 also assumes that, if Ms. Magna goes for the big time by buying a turbo-

prop, there is nothing that she can do if demand turns out to be unexpectedly low.

That is unrealistic. If business in the first year is poor, it may pay for Ms. Magna to

sell the turboprop and abandon the venture entirely. In Figure 10.8 we could rep-

resent this option to bail out by adding an extra decision point (a further square)

if the company buys the turboprop and first-year demand is low. If that happens,

Ms. Magna could decide either to sell the plane or to hold on and hope demand re-

covers. If the abandonment option is sufficiently valuable, it may make sense to

take the turboprop and shoot for the big payoff.

Pro and Con Decision Trees

Any cash-flow forecast rests on some assumption about the firm’s future invest-

ment and operating strategy. Often that assumption is implicit. Decision trees force

the underlying strategy into the open. By displaying the links between today’s and

117 52 65, or $65,000

52, or $52,000

.63.814102 .2118024 .43.412202 .6110024

11.102

2

NPV 250

.611002 .41502

1.10

550

102

1.10

670

11.102

2

96, or $96,000

.63.819602 .2122024 .43.419302 .6114024

11.102

2

NPV 550

.611502 .41302

1.10

NPV 250

.615502 .411852

1.10

117, or $117,000

276 PART III Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

10. A Project is Not a Black

Box

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

tomorrow’s decisions, they help the financial manager to find the strategy with the

highest net present value.

The trouble with decision trees is that they get so _____ complex so _____

quickly (insert your own expletives). What will Magna Charter do if demand is

neither high nor low but just middling? In that event Ms. Magna might sell the tur-

boprop and buy a piston-engine plane, or she might defer expansion and aban-

donment decisions until year 2. Perhaps middling demand requires a decision

about a price cut or an intensified sales campaign.

We could draw a new decision tree covering this expanded set of events and

decisions. Try it if you like: You’ll see how fast the circles, squares, and branches

accumulate.

Life is complex, and there is very little we can do about it. It is therefore unfair

to criticize decision trees because they can become complex. Our criticism is re-

served for analysts who let the complexity become overwhelming. The point of

decision trees is to allow explicit analysis of possible future events and decisions.

They should be judged not on their comprehensiveness but on whether they

show the most important links between today’s and tomorrow’s decisions. Deci-

sion trees used in real life will be more complex than Figure 10.8, but they will

nevertheless display only a small fraction of possible future events and decisions.

Decision trees are like grapevines: They are productive only if they are vigor-

ously pruned.

Decision trees can help identify the future choices available to the manager

and can give a clearer view of the cash flows and risks of a project. However, our

analysis of the Magna Charter project begged an important question. The option

to expand enlarged the spread of possible outcomes and therefore increased the

risk of investing in a piston aircraft. Conversely, the option to bail out would

narrow the spread of possible outcomes, reducing the risk of investment. We

should have used different discount rates to recognize these changes in risk, but

decision trees do not tell us how to do this. But the situation is not hopeless.

Modern techniques of option pricing can value these investment options. We

will describe these techniques in Chapters 20 and 21, and turn again to real op-

tions in Chapter 22.

Decision Trees and Monte Carlo Simulation

We have said that any cash-flow forecast rests on assumptions about future in-

vestment and operating strategy. Think back to the Monte Carlo simulation model

that we constructed for Otobai’s electric scooter project. What strategy was that

based on? We don’t know. Inevitably Otobai will face decisions about pricing, pro-

duction, expansion, and abandonment, but the model builder’s assumptions about

these decisions are buried in the model’s equations. The model builder may have

implicitly identified a future strategy for Otobai, but it is clearly not the optimal

one. There will be some runs of the model when nearly everything goes wrong and

when in real life Otobai would abandon to cut its losses. Yet the model goes on pe-

riod after period, heedless of the drain on Otobai’s cash resources. The most unfa-

vorable outcomes reported by the simulation model would never be encountered

in real life.

On the other hand, the simulation model probably understates the project’s po-

tential value if nearly everything goes right: There is no provision for expanding to

take advantage of good luck.

CHAPTER 10

A Project Is Not a Black Box 277