Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

We have focused on using the capital asset pricing model to estimate the ex-

pected returns on Union Pacific’s common stock. But it would be useful to get a

check on this figure. For example, in Chapter 4 we used the constant-growth

DCF formula to estimate the expected rate of return for a sample of utility

stocks.

9

You could also use DCF models with varying future growth rates, or

perhaps arbitrage pricing theory (APT). We showed in Section 8.4 how APT can

be used to estimate expected returns.

⫽ 3.5 ⫹ .518.02⫽ 7.5%

Expected stock return ⫽ r

f

⫹1r

m

⫺ r

f

2

CHAPTER 9 Capital Budgeting and Risk 227

9

The United States Surface Transportation Board uses the constant-growth model to estimate the cost

of equity capital for railroad companies. We will review its findings in Chapter 19.

9.3 CAPITAL STRUCTURE AND THE COMPANY COST

OF CAPITAL

In the last section, we used the capital asset pricing model to estimate the return

that investors require from Union Pacific’s common stock. Is this figure Union Pa-

cific’s company cost of capital? Not if Union Pacific has other securities outstand-

ing. The company cost of capital also needs to reflect the returns demanded by the

owners of these securities.

We will return shortly to the problem of Union Pacific’s cost of capital, but first

we need to look at the relationship between the cost of capital and the mix of debt

and equity used to finance the company. Think again of what the company cost of

capital is and what it is used for. We define it as the opportunity cost of capital for

the firm’s existing assets; we use it to value new assets that have the same risk as

the old ones.

If you owned a portfolio of all the firm’s securities—100 percent of the debt

and 100 percent of the equity—you would own the firm’s assets lock, stock, and

barrel. You wouldn’t share the cash flows with anyone; every dollar of cash the

firm paid out would be paid to you. You can think of the company cost of capi-

tal as the expected return on this hypothetical portfolio. To calculate it, you just

take a weighted average of the expected returns on the debt and the equity:

For example, suppose that the firm’s market-value balance sheet is as follows:

Asset value 100 Debt value (D)30

Equity value (E)70

Asset value 100 Firm value (V) 100

Note that the values of debt and equity add up to the firm value (D ⫹ E ⫽ V) and

that the firm value equals the asset value. (These figures are market values, not book

values: The market value of the firm’s equity is often substantially different from

its book value.)

⫽

debt

debt ⫹ equity

r

debt

⫹

equity

debt ⫹ equity

r

equity

Company cost of capital ⫽ r

assets

⫽ r

portfolio

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

If investors expect a return of 7.5 percent on the debt and 15 percent on the eq-

uity, then the expected return on the assets is

If the firm is contemplating investment in a project that has the same risk as the

firm’s existing business, the opportunity cost of capital for this project is the same

as the firm’s cost of capital; in other words, it is 12.75 percent.

What would happen if the firm issued an additional 10 of debt and used the cash

to repurchase 10 of its equity? The revised market-value balance sheet is

Asset value 100 Debt value (D)40

Equity value (E)60

Asset value 100 Firm value (V) 100

The change in financial structure does not affect the amount or risk of the cash

flows on the total package of debt and equity. Therefore, if investors required a re-

turn of 12.75 percent on the total package before the refinancing, they must require

a 12.75 percent return on the firm’s assets afterward.

Although the required return on the package of debt and equity is unaffected, the

change in financial structure does affect the required return on the individual se-

curities. Since the company has more debt than before, the debtholders are likely

to demand a higher interest rate. We will suppose that the expected return on the

debt rises to 7.875 percent. Now you can write down the basic equation for the re-

turn on assets

and solve for the return on equity

Increasing the amount of debt increased debtholder risk and led to a rise in the

return that debtholders required (r

debt

rose from 7.5 to 7.875 percent). The higher

leverage also made the equity riskier and increased the return that shareholders re-

quired (r

equity

rose from 15 to 16 percent). The weighted average return on debt and

equity remained at 12.75 percent:

Suppose that the company decided instead to repay all its debt and to replace it

with equity. In that case all the cash flows would go to the equity holders. The com-

pany cost of capital, r

assets

, would stay at 12.75 percent, and r

equity

would also be

12.75 percent.

⫽ 1.4 ⫻ 7.8752⫹ 1.6 ⫻ 162⫽ 12.75%

r

assets

⫽ 1.4 ⫻ r

debt

2⫹ 1.6 ⫻ r

equity

2

r

equity

⫽ 16.0%

⫽ a

40

100

⫻ 7.875 b⫹ a

60

100

⫻ r

equity

b⫽ 12.75%

r

assets

⫽

D

V

r

debt

⫹

E

V

r

equity

⫽ a

30

100

⫻ 7.5 b⫹ a

70

100

⫻ 15 b⫽ 12.75%

r

assets

⫽

D

V

r

debt

⫹

E

V

r

equity

228 PART II Risk

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

How Changing Capital Structure Affects Beta

We have looked at how changes in financial structure affect expected return. Let us

now look at the effect on beta.

The stockholders and debtholders both receive a share of the firm’s cash flows,

and both bear part of the risk. For example, if the firm’s assets turn out to be worth-

less, there will be no cash to pay stockholders or debtholders. But debtholders usu-

ally bear much less risk than stockholders. Debt betas of large blue-chip firms are

typically in the range of .1 to .3.

10

If you owned a portfolio of all the firm’s securities, you wouldn’t share the cash

flows with anyone. You wouldn’t share the risks with anyone either; you would

bear them all. Thus the firm’s asset beta is equal to the beta of a portfolio of all the

firm’s debt and its equity.

The beta of this hypothetical portfolio is just a weighted average of the debt and

equity betas:

Think back to our example. If the debt before the refinancing has a beta of .1 and

the equity has a beta of 1.1, then

What happens after the refinancing? The risk of the total package is unaffected, but

both the debt and the equity are now more risky. Suppose that the debt beta in-

creases to .2. We can work out the new equity beta:

You can see why borrowing is said to create financial leverage or gearing. Financial

leverage does not affect the risk or the expected return on the firm’s assets, but it

does push up the risk of the common stock. Shareholders demand a correspond-

ingly higher return because of this financial risk.

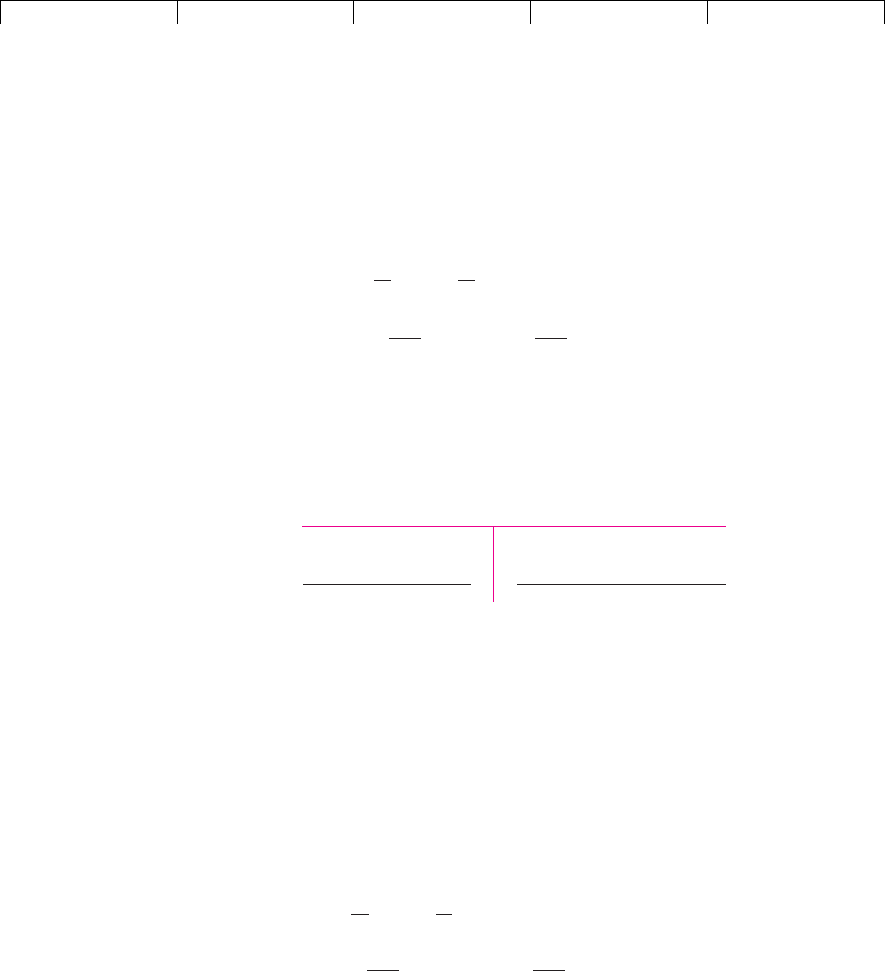

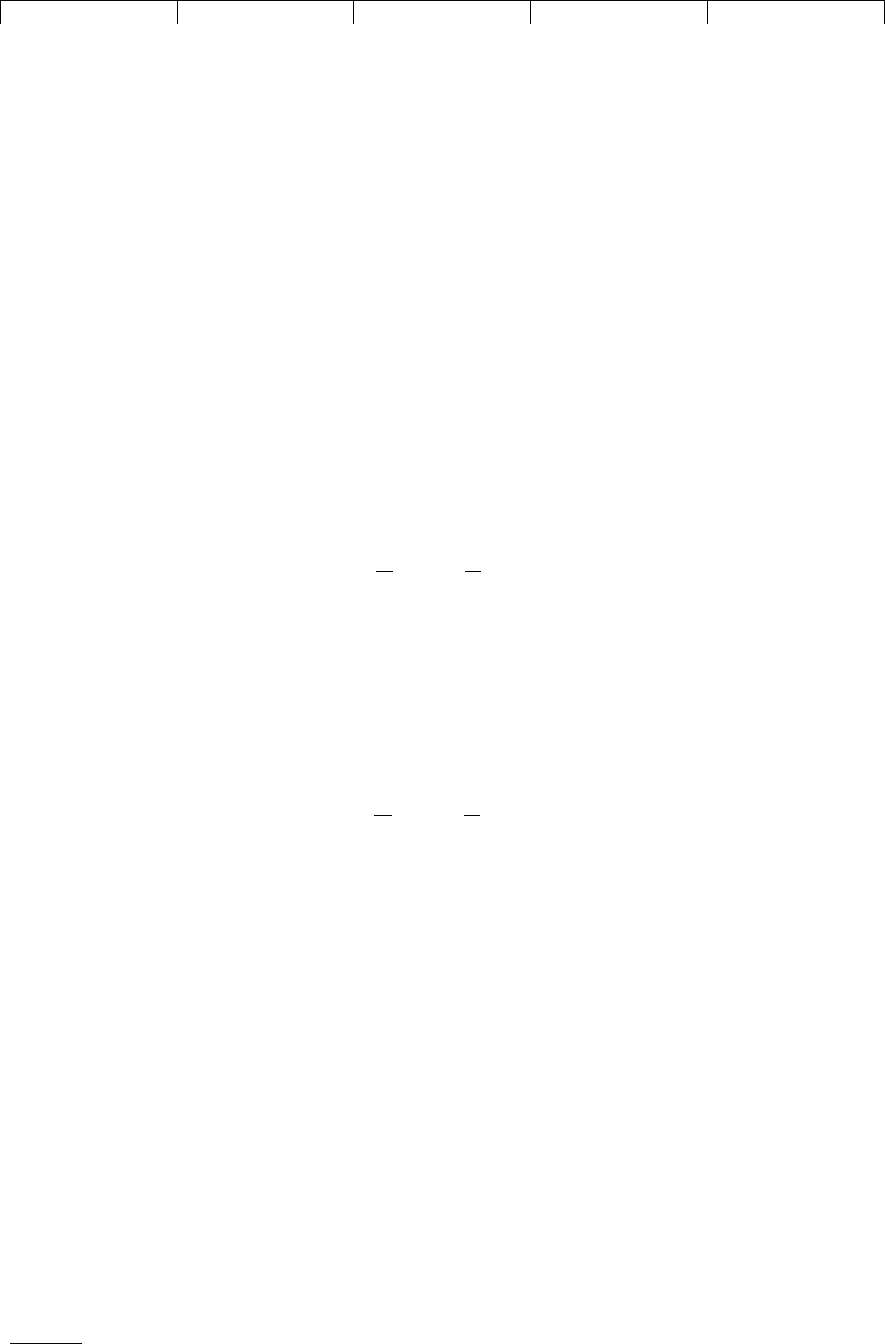

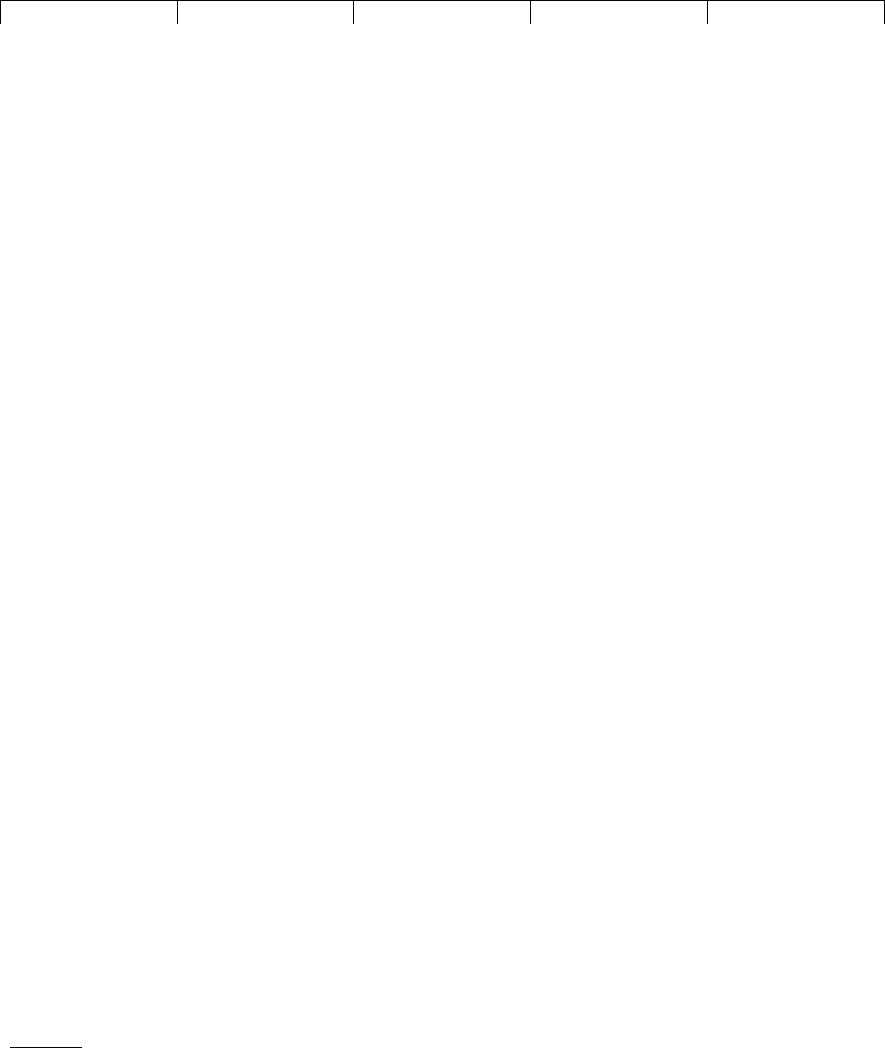

Figure 9.3 shows the expected return and beta of the firm’s assets. It also shows

how expected return and risk are shared between the debtholders and equity hold-

ers before the refinancing. Figure 9.4 shows what happens after the refinancing.

Both debt and equity are now more risky, and therefore investors demand a higher

return. But equity accounts for a smaller proportion of firm value than before. As

a result, the weighted average of both the expected return and beta on the two

components is unchanged.

Now you can see how to unlever betas, that is, how to go from an observed

equity

to

assets.

You have the equity beta, say, 1.2. You also need the debt beta, say,

.2, and the relative market values of debt (D/V) and equity (E/V). If debt accounts

for 40 percent of overall value V,

assets

⫽ 1.4 ⫻ .22⫹ 1.6 ⫻ 1.22⫽ .8

equity

⫽ 1.2

.8 ⫽ 1.4 ⫻ .22⫹ 1.6 ⫻

equity

2

assets

⫽

portfolio

⫽

D

V

dept

⫹

E

V

equity

assets

⫽ 1.3 ⫻ .12⫹ 1.7 ⫻ 1.12⫽ .8

assets

⫽

portfolio

⫽

D

V

debt

⫹

E

V

equity

CHAPTER 9 Capital Budgeting and Risk 229

10

For example, in Table 7.1 we reported average returns on a portfolio of high-grade corporate bonds.

In the 10 years ending December 2000 the estimated beta of this bond portfolio was .17.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

This runs the previous example in reverse. Just remember the basic relationship:

Capital Structure and Discount Rates

The company cost of capital is the opportunity cost of capital for the firm’s as-

sets. That’s why we write it as r

assets.

If a firm encounters a project that has the

assets

⫽

portfolio

⫽

D

V

debt

⫹

E

V

equity

230 PART II Risk

Beta

0 b

debt

= .1 b

assets

= .8 b

equity

= 1.1

Expected return,

percent

r

debt

= 7.5

r

assets

= 12.75

r

equity

= 15

FIGURE 9.3

Expected returns and betas

before refinancing. The

expected return and beta

of the firm’s assets are

weighted averages of the

expected return and betas

of the debt and equity.

Beta

0 b

debt

= .2 b

assets

= .8 b

equity

= 1.2

Expected return,

percent

r

debt

= 7.875

r

assets

= 12.75

r

equity

= 16

FIGURE 9.4

Expected returns and betas

after refinancing.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

same beta as the firm’s overall assets, then r

assets

is the right discount rate for the

project cash flows.

When the firm uses debt financing, the company cost of capital is not the same

as r

equity

, the expected rate of return on the firm’s stock; r

equity

is higher because of

financial risk. However, the company cost of capital can be calculated as a

weighted average of the returns expected by investors on the various debt and eq-

uity securities issued by the firm. You can also calculate the firm’s asset beta as a

weighted average of the betas of these securities.

When the firm changes its mix of debt and equity securities, the risk and ex-

pected returns of these securities change; however, the asset beta and the company

cost of capital do not change.

Now, if you think all this is too neat and simple, you’re right. The complica-

tions are spelled out in great detail in Chapters 17 through 19. But we must note

one complication here: Interest paid on a firm’s borrowing can be deducted from

taxable income. Thus the after-tax cost of debt is r

debt

(l ⫺ T

c

), where T

c

is the

marginal corporate tax rate. When companies discount an average-risk project,

they do not use the company cost of capital as we have computed it. They use

the after-tax cost of debt to compute the after-tax weighted-average cost of cap-

ital or WACC:

More—lots more—on this in Chapter 19.

Back to Union Pacific’s Cost of Capital

In the last section we estimated the return that investors required on Union Pa-

cific’s common stock. If Union Pacific were wholly equity-financed, the company

cost of capital would be the same as the expected return on its stock. But in mid-

2001 common stock accounted for only 60 percent of the market value of the com-

pany’s securities. Debt accounted for the remaining 40 percent.

11

Union Pacific’s

company cost of capital is a weighted average of the expected returns on the dif-

ferent securities.

We estimated the expected return from Union Pacific’s common stock at 7.5 per-

cent. The yield on the company’s debt in 2001 was about 5.5 percent.

12

Thus

Union Pacific’s WACC is calculated in the same fashion, but using the after-tax cost

of debt.

⫽ a

40

100

⫻ 5.5 b⫹ a

60

100

⫻ 7.5 b⫽ 6.7%

Company cost of capital ⫽ r

assets

⫽

D

V

r

debt

⫹

E

V

r

equity

WACC ⫽ r

debt

11 ⫺ T

c

2

D

V

⫹ r

equity

E

V

CHAPTER 9

Capital Budgeting and Risk 231

11

Union Pacific had also issued preferred stock. Preferred stock is discussed in Chapter 14. To keep mat-

ters simple here, we have lumped the preferred stock in with Union Pacific’s debt.

12

This is a promised yield; that is, it is the yield if Union Pacific makes all the promised payments. Since

there is some risk of default, the expected return is always less than the promised yield. Union Pacific

debt has an investment-grade rating and the difference is small. But for a company that is hovering on

the brink of bankruptcy, it can be important.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

We have shown how the CAPM can help to estimate the cost of capital for domes-

tic investments by U.S. companies. But can we extend the procedure to allow for

investments in different countries? The answer is yes in principle, but naturally

there are complications.

Foreign Investments Are Not Always Riskier

Pop quiz: Which is riskier for an investor in the United States—the Standard and

Poor’s Composite Index or the stock market in Egypt? If you answer Egypt, you’re

right, but only if risk is defined as total volatility or variance. But does investment

in Egypt have a high beta? How much does it add to the risk of a diversified port-

folio held in the United States?

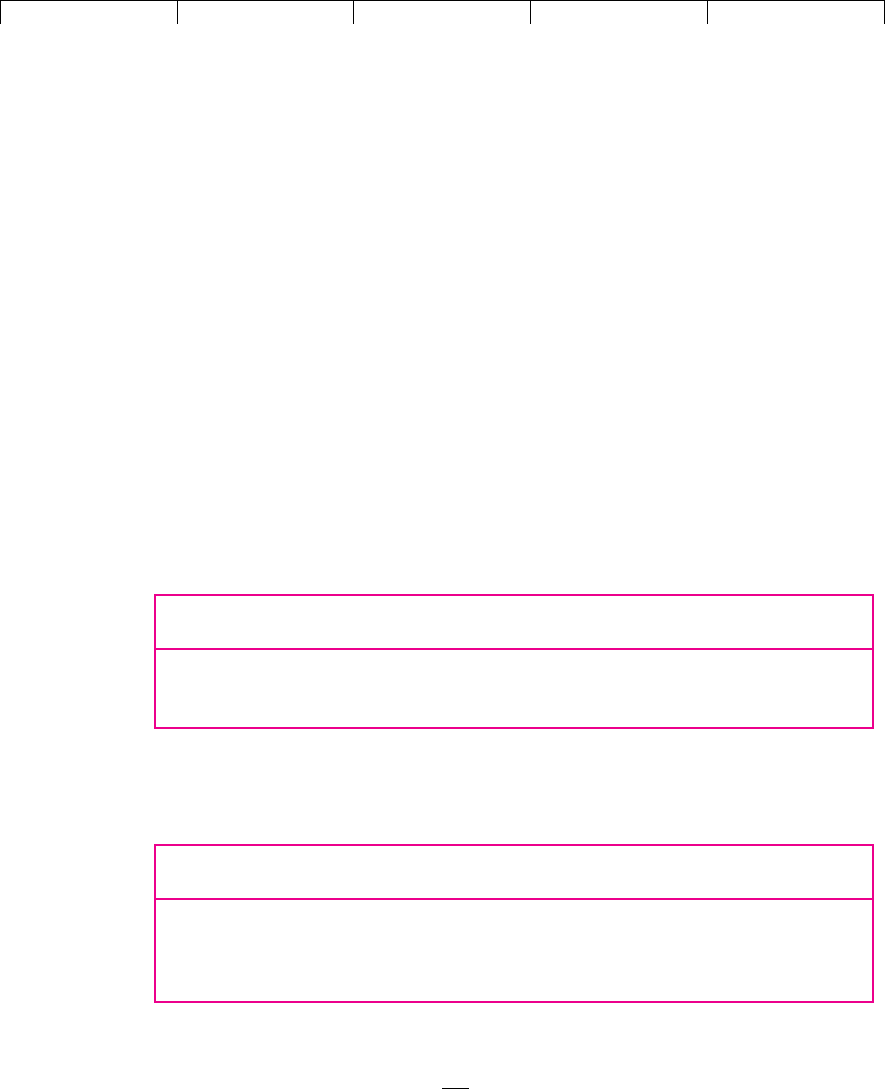

Table 9.2 shows estimated betas for the Egyptian market and for markets in

Poland, Thailand, and Venezuela. The standard deviations of returns in these mar-

kets were two or three times more than the U.S. market, but only Thailand had a

beta greater than 1. The reason is low correlation. For example, the standard devi-

ation of the Egyptian market was 3.1 times that of the Standard and Poor’s index,

but the correlation coefficient was only .18. The beta was 3.1 ⫻ .18 ⫽ .55.

Table 9.2 does not prove that investment abroad is always safer than at home.

But it should remind you always to distinguish between diversifiable and market

risk. The opportunity cost of capital should depend on market risk.

Foreign Investment in the United States

Now let’s turn the problem around. Suppose that the Swiss pharmaceutical com-

pany, Roche, is considering an investment in a new plant near Basel in Switzerland.

The financial manager forecasts the Swiss franc cash flows from the project and dis-

counts these cash flows at a discount rate measured in francs. Since the project is

risky, the company requires a higher return than the Swiss franc interest rate. How-

ever, the project is average-risk compared to Roche’s other Swiss assets. To esti-

mate the cost of capital, the Swiss manager proceeds in the same way as her coun-

terpart in a U.S. pharmaceutical company. In other words, she first measures the

risk of the investment by estimating Roche’s beta and the beta of other Swiss phar-

maceutical companies. However, she calculates these betas relative to the Swiss mar-

ket index. Suppose that both measures point to a beta of 1.1 and that the expected

232 PART II

Risk

9.4 DISCOUNT RATES FOR INTERNATIONAL

PROJECTS

Ratio of

Standard Correlation

Deviations* Coefficient Beta

†

Egypt 3.11 .18 .56

Poland 1.93 .42 .81

Thailand 2.91 .48 1.40

Venezuela 2.58 .30 .77

TABLE 9.2

Betas of four country indexes versus the U.S. market,

calculated from monthly returns, August 1996–July 2001.

Despite high volatility, three of the four betas are less

than 1. The reason is the relatively low correlation with

the U.S. market.

*Ratio of standard deviations of country index to Standard

& Poor’s Composite Index.

†

Beta is the ratio of covariance to variance. Covariance can be

written as

IM

⫽

IM

I

M

; ⫽

IM

I

M

/

M

2

⫽(

I

/

M

), where

I indicates the country index and M indicates the U.S. market.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

risk premium on the Swiss market index is 6 percent.

13

Then Roche needs to dis-

count the Swiss franc cash flows from its project at 1.1 ⫻ 6 ⫽ 6.6 percent above the

Swiss franc interest rate.

That’s straightforward. But now suppose that Roche considers construction of a

plant in the United States. Once again the financial manager measures the risk of

this investment by its beta relative to the Swiss market index. But notice that the

value of Roche’s business in the United States is likely to be much less closely tied

to fluctuations in the Swiss market. So the beta of the U.S. project relative to the

Swiss market is likely to be less than 1.1. How much less? One useful guide is the

U.S. pharmaceutical industry beta calculated relative to the Swiss market index. It

turns out that this beta has been .36.

14

If the expected risk premium on the Swiss

market index is 6 percent, Roche should be discounting the Swiss franc cash flows

from its U.S. project at .36 ⫻ 6 ⫽ 2.2 percent above the Swiss franc interest rate.

Why does Roche’s manager measure the beta of its investments relative to the

Swiss index, whereas her U.S. counterpart measures the beta relative to the U.S.

index? The answer lies in Section 7.4, where we explained that risk cannot be con-

sidered in isolation; it depends on the other securities in the investor’s portfolio.

Beta measures risk relative to the investor’s portfolio. If U.S. investors already hold

the U.S. market, an additional dollar invested at home is just more of the same.

But, if Swiss investors hold the Swiss market, an investment in the United States

can reduce their risk. That explains why an investment in the United States is

likely to have lower risk for Roche’s shareholders than it has for shareholders in

Merck or Pfizer. It also explains why Roche’s shareholders are willing to accept

a lower return from such an investment than would the shareholders in the U.S.

companies.

15

When Merck measures risk relative to the U.S. market and Roche measures risk

relative to the Swiss market, their managers are implicitly assuming that the share-

holders simply hold domestic stocks. That’s not a bad approximation, particularly

in the case of the United States.

16

Although investors in the United States can re-

duce their risk by holding an internationally diversified portfolio of shares, they

generally invest only a small proportion of their money overseas. Why they are so

shy is a puzzle.

17

It looks as if they are worried about the costs of investing over-

seas, but we don’t understand what those costs include. Maybe it is more difficult

to figure out which foreign shares to buy. Or perhaps investors are worried that a

CHAPTER 9

Capital Budgeting and Risk 233

13

Figure 7.3 showed that this is the historical risk premium on the Swiss market. The fact that the real-

ized premium has been lower in Switzerland than the United States may be just a coincidence and may

not mean that Swiss investors expected the lower premium. On the other hand, if Swiss firms are gen-

erally less risky, then investors may have been content with a lower premium.

14

This is the beta of the Standard and Poor’s pharmaceutical index calculated relative to the Swiss mar-

ket for the period August 1996 to July 2001.

15

When investors hold efficient portfolios, the expected reward for risk on each stock in the portfolio is

proportional to its beta relative to the portfolio. So, if the Swiss market index is an efficient portfolio for

Swiss investors, then Swiss investors will want Roche to invest in a new plant if the expected reward

for risk is proportional to its beta relative to the Swiss market index.

16

But it can be a bad assumption elsewhere. For small countries with open financial borders—

Luxembourg, for example—a beta calculated relative to the local market has little value. Few in-

vestors in Luxembourg hold only local stocks.

17

For an explanation of the cost of capital for international investments when there are costs to interna-

tional diversification, see I. A. Cooper and E. Kaplanis, “Home Bias in Equity Portfolios and the Cost of

Capital for Multinational Firms,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 8 (Fall 1995), pp. 95–102.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

foreign government will expropriate their shares, restrict dividend payments, or

catch them by a change in the tax law.

However, the world is getting smaller, and investors everywhere are increasing

their holdings of foreign securities. Large American financial institutions have sub-

stantially increased their overseas investments, and literally dozens of funds have

been set up for individuals who want to invest abroad. For example, you can now

buy funds that specialize in investment in emerging capital markets such as Viet-

nam, Peru, or Hungary. As investors increase their holdings of overseas stocks, it

becomes less appropriate to measure risk relative to the domestic market and more

important to measure the risk of any investment relative to the portfolios that they

actually hold.

Who knows? Perhaps in a few years investors will hold internationally di-

versified portfolios, and in later editions of this book we will recommend that

firms calculate betas relative to the world market. If investors throughout the

world held the world portfolio, then Roche and Merck would both demand the

same return from an investment in the United States, in Switzerland, or in

Egypt.

Do Some Countries Have a Lower Cost of Capital?

Some countries enjoy much lower rates of interest than others. For example, as we

write this the interest rate in Japan is effectively zero; in the United States it is above

3 percent. People often conclude from this that Japanese companies enjoy a lower

cost of capital.

This view is one part confusion and one part probable truth. The confusion

arises because the interest rate in Japan is measured in yen and the rate in the

United States is measured in dollars. You wouldn’t say that a 10-inch-high rabbit

was taller than a 9-foot elephant. You would be comparing their height in different

units. In the same way it makes no sense to compare an interest rate in yen with a

rate in dollars. The units are different.

But suppose that in each case you measure the interest rate in real terms. Then

you are comparing like with like, and it does make sense to ask whether the costs

of overseas investment can cause the real cost of capital to be lower in Japan. Japan-

ese citizens have for a long time been big savers, but as they moved into a new cen-

tury they were very worried about the future and were saving more than ever. That

money could not be absorbed by Japanese industry and therefore had to be in-

vested overseas. Japanese investors were not compelled to invest overseas: They

needed to be enticed to do so. So the expected real returns on Japanese investments

fell to the point that Japanese investors were willing to incur the costs of buying

foreign securities, and when a Japanese company wanted to finance a new project,

it could tap into a pool of relatively low-cost funds.

234 PART II

Risk

9.5 SETTING DISCOUNT RATES WHEN YOU

CAN’T CALCULATE BETA

Stock or industry betas provide a rough guide to the risk encountered in various

lines of business. But an asset beta for, say, the steel industry can take us only so

far. Not all investments made in the steel industry are typical. What other kinds of

evidence about business risk might a financial manager examine?

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

In some cases the asset is publicly traded. If so, we can simply estimate its beta

from past price data. For example, suppose a firm wants to analyze the risks of

holding a large inventory of copper. Because copper is a standardized, widely

traded commodity, it is possible to calculate rates of return from holding copper

and to calculate a beta for copper.

What should a manager do if the asset has no such convenient price record?

What if the proposed investment is not close enough to business as usual to justify

using a company cost of capital?

These cases clearly call for judgment. For managers making that kind of judg-

ment, we offer two pieces of advice.

1. Avoid fudge factors. Don’t give in to the temptation to add fudge factors to

the discount rate to offset things that could go wrong with the proposed

investment. Adjust cash-flow forecasts first.

2. Think about the determinants of asset betas. Often the characteristics of high-

and low-beta assets can be observed when the beta itself cannot be.

Let us expand on these two points.

Avoid Fudge Factors in Discount Rates

We have defined risk, from the investor’s viewpoint, as the standard deviation of

portfolio return or the beta of a common stock or other security. But in everyday

usage risk simply equals “bad outcome.” People think of the risks of a project as a

list of things that can go wrong. For example,

• A geologist looking for oil worries about the risk of a dry hole.

• A pharmaceutical manufacturer worries about the risk that a new drug which

cures baldness may not be approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

• The owner of a hotel in a politically unstable part of the world worries about

the political risk of expropriation.

Managers often add fudge factors to discount rates to offset worries such as these.

This sort of adjustment makes us nervous. First, the bad outcomes we cited ap-

pear to reflect unique (i.e., diversifiable) risks that would not affect the expected

rate of return demanded by investors. Second, the need for a discount rate adjust-

ment usually arises because managers fail to give bad outcomes their due weight

in cash-flow forecasts. The managers then try to offset that mistake by adding a

fudge factor to the discount rate.

Example Project Z will produce just one cash flow, forecasted at $1 million at

year 1. It is regarded as average risk, suitable for discounting at a 10 percent com-

pany cost of capital:

But now you discover that the company’s engineers are behind schedule in devel-

oping the technology required for the project. They’re confident it will work, but

they admit to a small chance that it won’t. You still see the most likely outcome as

$1 million, but you also see some chance that project Z will generate zero cash flow

next year.

PV ⫽

C

1

1 ⫹ r

⫽

1,000,000

1.1

⫽ $909,100

CHAPTER 9 Capital Budgeting and Risk 235

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

II. Risk 9. Capital Budgeting and

Risk

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Now the project’s prospects are clouded by your new worry about technology.

It must be worth less than the $909,100 you calculated before that worry arose. But

how much less? There is some discount rate (10 percent plus a fudge factor) that will

give the right value, but we don’t know what that adjusted discount rate is.

We suggest you reconsider your original $1 million forecast for project Z’s cash

flow. Project cash flows are supposed to be unbiased forecasts, which give due

weight to all possible outcomes, favorable and unfavorable. Managers making un-

biased forecasts are correct on average. Sometimes their forecasts will turn out

high, other times low, but their errors will average out over many projects.

If you forecast cash flow of $1 million for projects like Z, you will overestimate

the average cash flow, because every now and then you will hit a zero. Those ze-

ros should be “averaged in” to your forecasts.

For many projects, the most likely cash flow is also the unbiased forecast. If there

are three possible outcomes with the probabilities shown below, the unbiased fore-

cast is $1 million. (The unbiased forecast is the sum of the probability-weighted

cash flows.)

236 PART II

Risk

Possible Probability-Weighted Unbiased

Cash Flow Probability Cash Flow Forecast

1.2 .25 .3

1.0 .50 .5 1.0, or $1 million

.8 .25 .2

This might describe the initial prospects of project Z. But if technological uncer-

tainty introduces a 10 percent chance of a zero cash flow, the unbiased forecast

could drop to $900,000:

Possible Probability-Weighted Unbiased

Cash Flow Probability Cash Flow Forecast

1.2 .225 .27

1.0 .45 .45 .90, or $900,000

.8 .225 .18

0 .10 .0

The present value is

Now, of course, you can figure out the right fudge factor to add to the discount

rate to apply to the original $1 million forecast to get the correct answer. But you

have to think through possible cash flows to get that fudge factor; and once you

have thought through the cash flows, you don’t need the fudge factor.

Managers often work out a range of possible outcomes for major projects,

sometimes with explicit probabilities attached. We give more elaborate exam-

ples and further discussion in Chapter 10. But even when a range of outcomes

and probabilities is not explicitly written down, the manager can still consider

the good and bad outcomes as well as the most likely one. When the bad out-

comes outweigh the good, the cash-flow forecast should be reduced until bal-

ance is regained.

PV ⫽

.90

1.1

⫽ .818, or $818,000

冧

冧