Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ENDOCRINE PROBLEMS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

567

Although the signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism

suggest sympathetic overactivity, plasma levels and secretion

rates of epinephrine and norepinephrine are actually normal

in patients with thyroid storm. Because of this, increased

sensitivity to catecholamines has been suggested, and ele-

vated cAMP levels in these patients have been cited as evi-

dence of increased adrenergic activity.

The mechanisms that lead to the decompensated state

characteristic of thyroid storm have not been well studied.

Higher levels of cytokines and immune dysregulation have

been implicated, but without conclusive data. The basal

metabolic rate and thermogenesis are increased, and there is

a net degradation of proteins. Although both protein synthe-

sis and degradation are increased, hyperthyroidism results in

negative nitrogen balance, muscle wasting, and reduced

albumin concentrations. Although cortisol clearance is

increased, its production rates are also increased, so the cor-

tisol levels remain essentially unchanged. Thyroid hormones

have direct cardiostimulatory effects, resulting in tachycardia

and increased contractility. Increased thermogenesis results

in vasodilatation as part of the compensatory response to

increased body temperature.

Clinical Features

Thyroid storm is usually seen in patients with known hyper-

thyroidism but may be the presenting feature in a patient with

previously undiagnosed thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm is seen

often in association with one of a long list of precipitating

conditions, but the two most common conditions are surgical

procedures of any kind—but particularly thyroid surgery in

an uncontrolled or poorly prepared hyperthyroid patient—

and infections. Thyroid storm is now quite uncommon fol-

lowing thyroid surgery because of preoperative preparation

and control of hyperthyroidism with antithyroid drugs.

Other potential precipitating factors include cardiovascu-

lar disease (including acute myocardial infarction), systemic

illness, trauma, diabetic ketoacidosis, vigorous palpation of

an untreated hyperthyroid gland, administration of iodi-

nated contrast material, stroke, and preeclampsia or eclamp-

sia. Rare cases of thyroid storm have been seen after

amiodarone administration. Exacerbation of hyperthy-

roidism may occur following radioactive iodine treatment of

Graves’ disease, but thyroid storm is unusual because most

hyperthyroid patients are well controlled by antithyroid drug

therapy. In contrast, thyroid storm may occur in hyperthy-

roid patients who discontinue antithyroid medications pre-

maturely or inadvertently. Patients who accidentally or

deliberately ingest an excessive amount of thyroid hormone

may present with severe hyperthyroidism but usually with-

out the complete picture seen in thyroid storm.

A. Symptoms and Signs—Thyroid storm is characterized

by clinical features of severe thyrotoxicosis with fever and

altered mental status. In one series of patients hospitalized

for complicated thyrotoxicosis, cardiovascular complications

and neuropsychiatric syndromes were the two most frequent

indications for admission. Mental status changes may

include confusion, agitation, overt psychosis, and in extreme

cases, even coma. Common cardiovascular manifestations

include tachycardia that is out of proportion to fever, cardiac

arrhythmias (sinus or supraventricular tachycardia, includ-

ing atrial fibrillation), and congestive heart failure. Patients

presenting with congestive heart failure are usually elderly

and have an underlying history of heart disease. However, it

is well documented that hyperthyroidism can cause conges-

tive heart failure even in the absence of underlying heart dis-

ease. Hypotension and shock may be late manifestations. GI

manifestations include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and

abdominal pain. Weight loss and cachexia are common.

Goiter is almost always present and may be diffuse or

multinodular. Since many of these patients have Graves’ dis-

ease, the goiter is more often diffuse and nontender. Patients

often have marked muscle weakness owing to proximal

myopathy and generalized cachexia. Tremor is present. The

skin is warm, moist, flushed, soft, and “velvety.” The reflexes

may be brisk. Graves’ disease patients also may have ophthal-

mopathy and dermopathy. Burch and Wartofsky have pro-

posed a point scale to facilitate the diagnosis of thyroid

storm, assigning points based on the severity of thermoregu-

latory dysfunction (temperature), cardiovascular dysfunc-

tion, CNS effects, GI-hepatic dysfunction, and precipitating

factors. That is, thyrotoxic patients with fever and dysfunc-

tion of one or more organ systems, particularly cardiovascu-

lar and CNS, are more likely to have severe thyrotoxicosis and

need hospitalization for aggressive treatment.

B. Laboratory Findings—Elevated aminotransferases,

hyperbilirubinemia, and hepatomegaly are common.

Alkaline phosphatase levels are also increased, but this usu-

ally represents an increase in the bone fraction rather than

the liver fraction. Serum calcium may be elevated as a reflec-

tion of increased bone resorption. Other laboratory abnor-

malities observed in patients hospitalized for complicated

thyrotoxicosis include hypo- or hypernatremia, hyper-

glycemia, and anemia.

The diagnosis of thyroid storm is essentially a clinical

one. The presence of high fever and altered mental status in

a severely ill patient with hyperthyroidism should warrant

aggressive treatment for thyrotoxic crisis. Laboratory tests of

thyroid function confirm the presence of hyperthyroidism,

that is, high total and free thyroxine (T

4

) and triiodothyro-

nine (T

3

) and a reduced and nearly undetectable thyrotropin

(TSH) level. However, T

3

and T

4

levels may be decreased by

concurrent nonthyroidal illness. Therefore, levels of T

4

and

T

3

may not correlate with the patient’s clinical picture.

Treatment

The management of thyroid storm can be discussed under

three broad categories: (1) control of hyperthyroidism,

(2) treatment of the precipitating illness, and (3) other

supportive measures. Treatment is summarized in Table 25–1.

CHAPTER 25

568

A. Control of Hyperthyroidism—Several therapeutic

agents that act by different mechanisms to block the synthe-

sis, secretion, activation, or action of thyroid hormones can

be used together for rapid control of hyperthyroidism.

1. Thioureas—Propylthiouracil, methimazole, and car-

bimazole inhibit thyroid hormone synthesis primarily by

inhibiting reactions catalyzed by the thyroid peroxidase

enzyme. These reactions include oxidation, organification,

and iodotyrosine coupling. Propylthiouracil is also a weak

inhibitor of peripheral conversion of T

4

to T

3

. Methimazole is

generally considered to be more potent than propylthiouracil.

In comatose patients with thyroid storm, propylthiouracil or

methimazole may be given through a nasogastric tube because

these drugs are not available in parenteral formulations.

There is no agreement about the optimal dosage of

antithyroid drugs. One regimen is to start propylthiouracil at

an initial dose of 600–1200 mg/day in four divided doses.

Alternatively, 60–120 mg/day methimazole can be given in

four divided doses. Should the patient be unable to take med-

ication orally, these medications can be administered rectally.

Others have advocated giving a loading dose of 600–1200 mg

propylthiouracil followed by 200–300 mg every 8 hours.

However, some investigators have questioned whether addi-

tional inhibition of thyroperoxidase is achievable at dosages

of propylthiouracil in excess of 300 mg daily. Methimazole

is given at one-tenth the preceding dosage. The serum half-

life of propylthiouracil is 75 minutes; of methimazole,

240–360 minutes. However, the intrathyroidal residence time

of methimazole is 20 hours, and its duration of action is

believed to be as long as 40 hours. These data have been used to

support once-daily administration of methimazole. However,

in the life-threatening situation of thyroid storm, it may be

preferable to give methimazole three or four times daily.

Propylthiouracil is also a weak inhibitor of 5′-deiodinase, the

enzyme that converts T

4

to T

3

, and this may be a minor advan-

tage over methimazole—although the two drugs have never

been compared directly. Propylthiouracil has been rarely asso-

ciated with pulmonary capillaritis and alveolar hemorrhage.

Resistance to the effects of antithyroid drugs is extremely

uncommon. Most cases of apparent resistance turn out to be

problems of noncompliance. Acute side effects of these drugs

are uncommon, but allergic reactions, leukopenia, and hepa-

totoxicity may occur.

2. Ipodate sodium—Ipodate sodium is an iodine-

containing radiocontrast agent used for gallbladder imaging.

It is one of the most potent inhibitors of 5′-deiodinase.

Clinical studies with ipodate in hyperthyroidism have shown

that the drug has an extremely rapid onset of action, result-

ing in marked lowering of serum T

3

levels within 4–6 hours

and normalization of serum T

3

levels within 24–48 hours.

The mechanism of antithyroid effect of ipodate is complex.

Besides inhibiting conversion of T

4

to T

3

, ipodate also lowers

serum T

4

levels, albeit to a lesser degree, indicating additional

direct effects on thyroid hormone synthesis. Reverse T

3

levels

are higher in ipodate-treated patients, an observation consis-

tent with drug-induced inhibition of 5′-deiodinase.

Although ipodate is an iodine-containing contrast agent,

radioiodine uptake studies in patients with Graves’ disease

treated with ipodate for more than a year revealed normal

uptake a week after discontinuation of ipodate therapy.

Ipodate sodium is administered orally as capsules con-

taining 500 mg. Recommended dosages range from 1–3

g/day. In obtunded patients, ipodate can be administered via

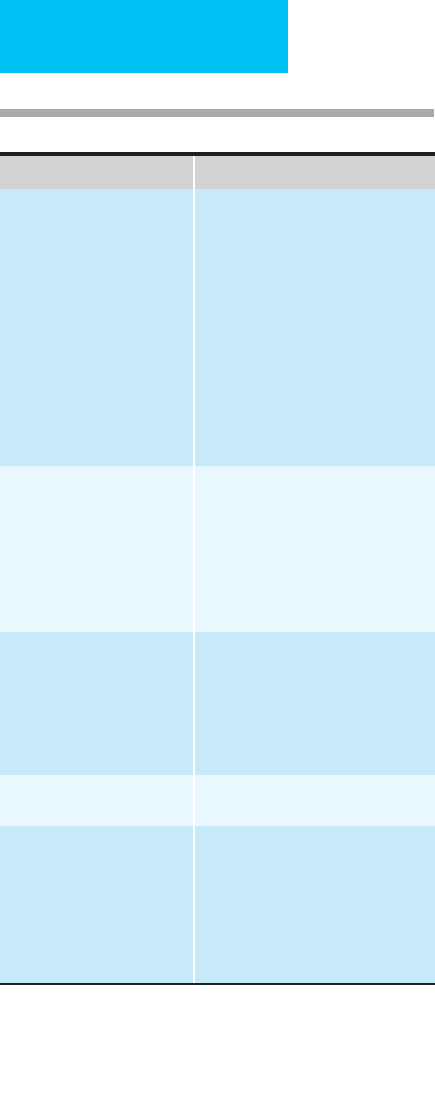

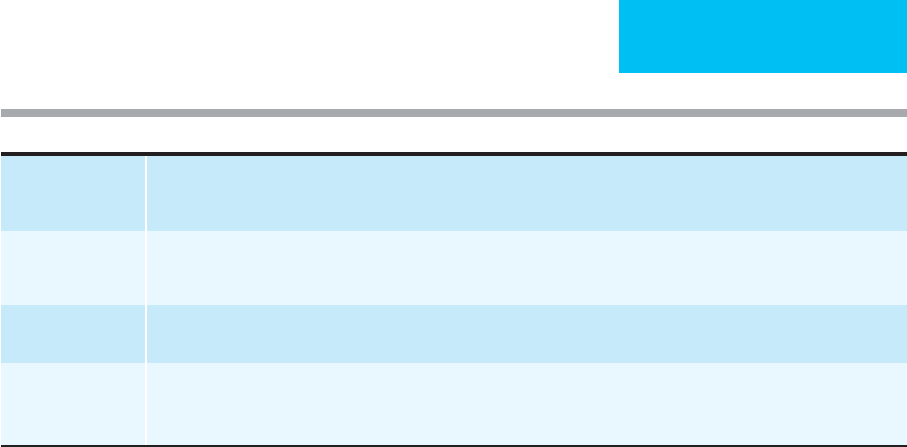

Mechanism of Action Treatment

Measures to reduce thyroid

hormone synthesis or

peripheral conversion of

T

4

to T

3

Propylthiouracil,

∗

200–300 mg orally

or through a nasogastric tube every

6 hours.

or

Propylthiouracil, 600 mg loading dose

orally, followed by 200–300 mg

every 8 hours.

or

Methimazole, 20–30 mg orally or

through a nasogastric tube every

6 hours.

plus

Ipodate,

†

1–1.5 g/d for the first

24 hours, then 500 mg twice daily.

Measures to inhibit the

release of thyroid hormones

Lugol’s solution, 5–10 drops three

times daily, or saturated solution of

sodium iodide, 3 drops three times

daily, after antithyroid therapy

(above) has been instituted.

Lithium carbonate, 300 mg every

8 hours, may be used in patients

with iodine allergy.

Sympathetic blockade Propranolol, 0.5–1 mg IV slowly over

5–10 minutes. Repeat every 3–4 hours

as indicated.

Contraindicated in COPD and asthma;

should be very carefully administered

in patients with congestive heart

failure.

Glucocorticoids Dexamethasone, 2–4 mg IV every

6–8 hours.

Supportive measures Identify and treat the precipitating

event.

Provide fluid and electrolyte replace-

ment as needed.

Hyperpyrexia: Cooling blankets, ice, or

cool sponges as necessary. Other

supportive measures.

∗

Both propylthiouracil and methimazole may be administered rectally.

†

If the patient is allergic to iodine, lithium may be used: lithium

carbonate, 300–400 mg every 8 hours. Serum lithium levels to be

maintained at approximately 1 meq/L.

Table 25–1. Treatment of thyroid storm.

ENDOCRINE PROBLEMS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

569

the intragastric route. It has been recommended that propy-

lthiouracil or methimazole be given prior to administration

of iodine-containing medications to prevent an iodide-

mediated exacerbation of hyperthyroidism.

3. Lithium—Lithium can be used in patients unable to tol-

erate iodine. Lithium is concentrated by the thyroid and

inhibits iodine uptake by the thyroid. It also inhibits thyroid

hormone release. A dosage of 300–400 mg every 8 hours can

be used temporarily to control the thyrotoxic patient who is

allergic to iodine. The dose should be adjusted as necessary

to maintain a serum lithium level of approximately 1 meq/L.

4. Iodide—Iodide blocks the release of thyroid hormones

from the gland. Iodide also has an inhibitory effect on thy-

roid hormone synthesis. High doses of inorganic iodide

decrease the yield of organic iodine within the thyroid

gland—a phenomenon referred to as the Wolff-Chaikoff

effect. However, this inhibitory effect on thyroid hormone

synthesis is transient, and in most patients, an escape from

this inhibition occurs with time.

Iodide should be administered only after synthesis of thy-

roid hormones has been inhibited by prior administration of

thioureas. Intravenous sodium iodide can be administered at

a dosage of 0.25 g every 6 hours. Alternatively, if the patient is

able to take medication orally, Lugol’s solution at a dosage of

5–10 drops three times a day or saturated potassium iodide

solution at a dose of 3 drops three times daily can be used.

Administration of a large dose of inorganic iodide pre-

dictably will reduce radioiodine uptake by the thyroid gland

for several weeks. Therefore, prior administration of inor-

ganic iodide will preclude subsequent treatment with

radioactive iodine for several weeks.

5. Propranolol—β-adrenergic blockers attenuate many of

the peripheral manifestations of hyperthyroidism. Thus

these agents can reverse the thyroid hormone-induced

increases in heart rate, cardiac output, and tremor. However,

weight loss is not affected by β-blockers. Propranolol, in

addition to its antiadrenergic properties, is a weak inhibitor

of 5′-deiodinase and thus lowers T

3

levels. The advantage of

the 5′-deiodinase inhibition property of propranolol is

unclear given the similar action of propylthiouracil and ipo-

date sodium. Other β-adrenergic blocking agents such as

esmolol and labetalol also have been used successfully.

The response to propranolol varies from patient to

patient, and dosages should be titrated to the clinical

response. The initial dose usually is 0.5–1 mg intravenously

given slowly over 5–10 minutes for a total of up to 10 mg.

This can be followed by 40–60 mg orally every 6 hours. If the

patient is unable to take medication orally, propranolol can

be administered intravenously in doses of 1–2 mg every 3–4

hours. These dosage recommendations are only general

guidelines to be used initially. Subsequent dosage adjust-

ments should be dictated by the clinical response.

Propranolol blood levels in the range of 50–100 μg/mL have

been shown to provide effective beta blockade. However,

blood levels of propranolol have not been used extensively in

clinical practice; it is much simpler to follow the heart rate

and blood pressure responses. Side effects of β-adrenergic

blockade in patients with thyroid storm include heart failure,

bradycardia, hypotension, and increased airway resistance.

6. Glucocorticoids—The older literature warned that

adrenal insufficiency might ensue in patients with thyroid

storm because of accelerated cortisol degradation. However,

this hypothesis has never been validated, and the routine use

of glucocorticoid replacement has declined. Glucocorticoids

do, however, have several salutary effects on thyroid function

in thyroid storm. In patients receiving thyroxine replace-

ment, glucocorticoids lower serum T

3

concentrations, prob-

ably by inhibition of peripheral 5′-deiodinase. In addition,

glucocorticoids lower serum T

4

levels in patients with

Graves’ disease. Finally, glucocorticoids in pharmacologic

doses inhibit TSH secretion. One recommended regimen is

2–4 mg dexamethasone every 6 hours intravenously. Patients

suspected of having adrenal insufficiency should be treated

accordingly with higher doses of hydrocortisone (see below).

7. Extracorporeal therapy—Exchange transfusion and

plasmapheresis have been advocated as ways of removing

large amounts of thyroid hormones from the circulation.

Experience with these techniques is limited. Furthermore,

with the availability of potent antithyroid drugs, they are not

likely to be needed.

B. General Supportive Measures—General measures

include fluid and electrolyte replacement and control of

hyperpyrexia. The latter may require the use of cooling blan-

kets. Salicylates should be avoided because these drugs can

inhibit T

4

and T

3

binding to the binding proteins and

increase the concentrations of the free T

4

and T

3

. In addition,

specific measures for prompt treatment of the precipitating

illness, cardiac arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure

should be initiated if indicated.

Prognosis

Most data on mortality statistics in thyroid storm are old, and

there are no recent series. Survival figures vary from 24–66%

in older series. The precipitating illness is clearly an important

determinant of prognosis. Many of these patients may require

admission to the ICU, and most require an extended hospital

stay; in one study, the median hospital stay was 12 days.

Basaria S, Cooper DS: Amiodarone and the thyroid. Am J Med

2005;118:706–14. [PMID: 15989900]

Cardenas GA, Cabral JM, Leslie CA: Amiodarone-induced thyro-

toxicosis: Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Cleve Clin J Med

2003;70:624–6. [PMID: 12882384]

Cooper DS: Antithyroid drugs. N Engl J Med 2005;352:905–17.

[PMID: 15745981]

Goldberg PA, Inzucchi SE: Critical issues in endocrinology. Clin

Chest Med 2003;24:583–606. [PMID: 14710692]

Nayak B, Burman K: Thyrotoxicosis and thyroid storm.

Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2006;3:663–86. [PMID:

17127140]

CHAPTER 25

570

Myxedema Coma

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Features of severe hypothyroidism (myxedema): dry,

rough, cold skin, nonpitting doughy edema, loss of eye-

brows and scalp hair, and delayed relaxation phase of

deep tendon reflexes.

Hypothermia.

Altered mental status or coma.

Hypercapnic respiratory failure.

General Considerations

Myxedema coma represents a breakdown of the body’s com-

pensatory mechanisms during the course of long-standing

severe hypothyroidism. Development of an intercurrent illness

such as an infection on top of the underlying severe hypothy-

roidism usually leads to this decompensation. Myxedema

coma is primarily a clinical diagnosis. While laboratory tests

confirm hypothyroidism, the diagnosis is based on the con-

stellation of clinical findings of myxedema, altered mental sta-

tus, and hypothermia. The physician must remain alert for the

possibility of myxedema coma because the consequences of

missing the diagnosis can be devastating. In addition, the usual

clinical signs of infection such as fever and leukocytosis may

be masked in patients with severe hypothyroidism. Therefore,

one also must actively search for infection or other precipitat-

ing factors and treat these illnesses aggressively.

Pathophysiology

Hypothyroidism is a common endocrinopathy, but

myxedema coma is encountered much less commonly

because of thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Myxedema coma is associated with poor outcome. Patients

with myxedema most often have a history of hypothy-

roidism, but the precipitating condition is almost always a

combination of failure to take an adequate amount of thy-

roid replacement therapy and the presence of some comor-

bid condition. Because the serum half-life of T

4

is quite long,

hypothyroidism is a subacute condition characterized by

decreased metabolic rate, accumulation of edema fluid, dete-

rioration of cardiac function from structural and physiologic

changes, hyperlipidemia, and inability to manifest an appro-

priate response to hypothermia. Ventilatory drive is dimin-

ished from central mechanisms and, because of respiratory

muscle weakness and pleural effusions and ascites, can result

in hypercapnia. Hyponatremia is common and results from

the inability to dilute urine maximally.

Clinical Features

Myxedema coma almost always occurs in patients with

known hypothyroidism but rarely can present as the initial

finding in hypothyroidism. A precipitating event usually can

be identified along with absent or inadequate thyroid replace-

ment therapy. The majority of cases of myxedema coma are

reported in winter months in regions with cold climates. Thus

cold exposure appears to be an important antecedent factor.

Other precipitating factors include sedative or anesthetic

drugs, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accidents,

trauma, infections, and a variety of other illnesses.

A. Symptoms and Signs—Most patients with myxedema

are elderly women. The classic signs of myxedema are pres-

ent, including puffy, expressionless face; dry, rough, and cold

skin; nonpitting, doughy edema; loss of eyebrows and scalp

hair; delayed relaxation phase of the tendon reflexes; and

enlarged tongue. Hypothermia is a hallmark of myxedema

coma, with core body temperatures as low as 21°C but more

often in the range of 32–35°C. Severe hypothermia (temper-

ature <32°C) is associated with a poor prognosis. However,

hypothermia can be easily overlooked if a thermometer that

can register temperatures below the usual range is not used.

Blood pressure may be normal, high, or low. The heart rate is

classically slow. Respirations may be slow and shallow

depending on the level of ventilatory drive and respiratory

muscle weakness. Mental status changes may include confu-

sion, somnolence, hallucinations, or coma. The thyroid gland

may not be palpable because of idiopathic atrophy, prior

radiation, or surgery.

Drug metabolism is significantly reduced in hypothy-

roidism, and administration of the usual doses of sedatives

may depress ventilation significantly and compromise men-

tal status. In critically ill patients, the diagnosis of hypothy-

roidism sometimes may be hard to make on clinical grounds.

B. Laboratory Findings—Hyponatremia is often present.

Arterial blood gases may reveal respiratory acidosis, hypercap-

nia, and hypoxemia. Hypoglycemia may occur, particularly if

there is deficiency of pituitary hormones as well. Chest x-ray

may reveal an enlarged cardiac silhouette and pleural and peri-

cardial effusions. The ECG may demonstrate low voltage,

sinus bradycardia, diffuse T-wave depression, nonspecific

ST-segment changes, and prolonged QT and PR intervals.

There may be conduction blocks as well. Cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF) pressure and protein concentrations may be increased.

Although myxedema coma is a clinical diagnosis, thyroid

function tests reveal low thyroxine (T

4

), low T

3

resin uptake,

and a high thyrotropin (TSH) level. It may be difficult at times

to distinguish sick euthyroid syndrome from primary hypothy-

roidism by thyroid function tests. Very high serum TSH levels

(>20 μU/mL) favor the diagnosis of primary hypothyroidism.

Moderately elevated TSH levels (up to 20 μU/mL) may be seen

occasionally in the course of sick euthyroid syndrome. Severe

nonthyroidal illness decreases the TSH response, and inappro-

priately low TSH is seen in secondary hypothyroidism owing

to hypothalamic or pituitary disorders.

C. Adrenal Insufficiency—In patients with hypothyroidism,

the manifestations of adrenal insufficiency may be masked.

This is important because adrenal insufficiency can coexist

ENDOCRINE PROBLEMS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

571

with hypothyroidism in two clinical situations. First, in

patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, there is a higher

incidence of autoimmune adrenalitis and adrenal insufficiency

than in the general population. Second, patients with panhy-

popituitarism may have absence of both TSH and adrenocor-

ticotropin (ACTH). These patients with secondary adrenal

insufficiency lack the skin and mucosal hyperpigmentation

that is characteristic of primary adrenal insufficiency. For

these reasons, it is easy to miss adrenal insufficiency in this set-

ting, and the clinician must keep alert to the possibility of con-

comitant adrenal insufficiency. A rapid ACTH stimulation test

should be performed in patients with myxedema. However, it

should be recognized that the cortisol response to ACTH may

be attenuated by hypothyroidism.

Treatment

Treatment consists of thyroid hormone replacement,

replacement of other necessary hormones, and supportive

measures (Table 25–2), including treatment of hypothermia

and of the precipitating illness.

A. Thyroid Hormone Replacement—While all commenta-

tors assert the need for prompt thyroid hormone replacement

in myxedema coma, there is disagreement about what consti-

tutes an optimal regimen. The major controversy relates

to which regimen of thyroid hormone replacement to use:

T

4

alone, T

3

alone, or a combination of T

4

and T

3

. The use of

T

3

alone has been advocated by some on physiologic grounds.

This is so because the activity of 5′-deiodinase is diminished

in hypothyroidism, and the conversion of T

4

to T

3

may be

limited. On the other hand, a rapid increase in T

3

may be

detrimental to the patient because of cardiac arrhythmias and

too rapid an increase in myocardial oxygen demand. Large

doses of T

3

(>75 μg) have been associated with increased

mortality. Because of its potential adverse effects, the use of

this regimen has been discouraged by some.

Intravenous administration of T

4

is considered safe and has

been the standard for the past three decades. One traditional

regimen consists of 500 μg of levothyroxine (T

4

) given slowly

intravenously, followed by 100–150 μg every 24 hours. The

rationale for the large initial dose is that it restores the total thy-

roxine pool. However, it is not clear if this regimen is any bet-

ter than 150 μg given intravenously daily. The rate of fall in

serum TSH levels is not significantly different between the two

regimens. In fact, a dose of 100–150 μg levothyroxine given

intravenously daily would correct the thermoregulatory, respi-

ratory, cardiac, and mental status changes over 24–48 hours.

A third regimen consists of a combination of both T

4

and

T

3

. It is suggested that 200–300 μg T

4

be given simultane-

ously with 25 μg T

3

intravenously. This is followed by admin-

istration of another 25 μg T

3

12 hours later and 100 μg T

4

at

24 hours. Starting the third day, 100 μg T

4

is given daily until

the patient regains consciousness.

Recent literature has witnessed conflicting reports on the

effectiveness of combined regimens of levothyroxine and

triiodothyronine. The rates of conversion of thyroxine to

triiodothyronine do vary in different tissues; animal studies

suggest that T

3

concentrations in some tissues of thyroidec-

tomized rats replaced with levothyroxine alone are lower

than those observed in euthyroid animals. Similarly, circulat-

ing levels of T

3

in hypothyroid patients treated with levothy-

roxine alone are lower than those in euthyroid individuals.

Objective differences between thyroxine replacement com-

pared with combined thyroxine plus triiodothyronine

replacement have not been found.

There is no strong basis for advocating any one regimen.

The rapid restoration of thyroid hormone levels is desirable.

Most authorities agree that expeditious thyroid hormone

replacement is a more important objective than the exact

regimen of thyroid hormone replacement and that high-dose

levothyroxine administered intravenously is a reasonable and

safe choice.

B. Glucocorticoids—As discussed earlier, signs of adrenal

insufficiency may be masked in hypothyroid patients. On the

other hand, initiation of levothyroxine therapy without con-

comitant glucocorticoid replacement may precipitate adre-

nal crisis if the patient has adrenal insufficiency. Therefore,

one must be on guard against the possibility of adrenal insuf-

ficiency in appropriate patients. If in doubt, it is better to err

on the side of treatment with corticosteroids (see “Adrenal

Insufficiency” next) because the consequences of delayed or

no replacement can be serious.

C. Supportive Measures—Patients with myxedema coma

may need transient endotracheal intubation and mechanical

ventilation for hypercapnic respiratory failure. Intravenous

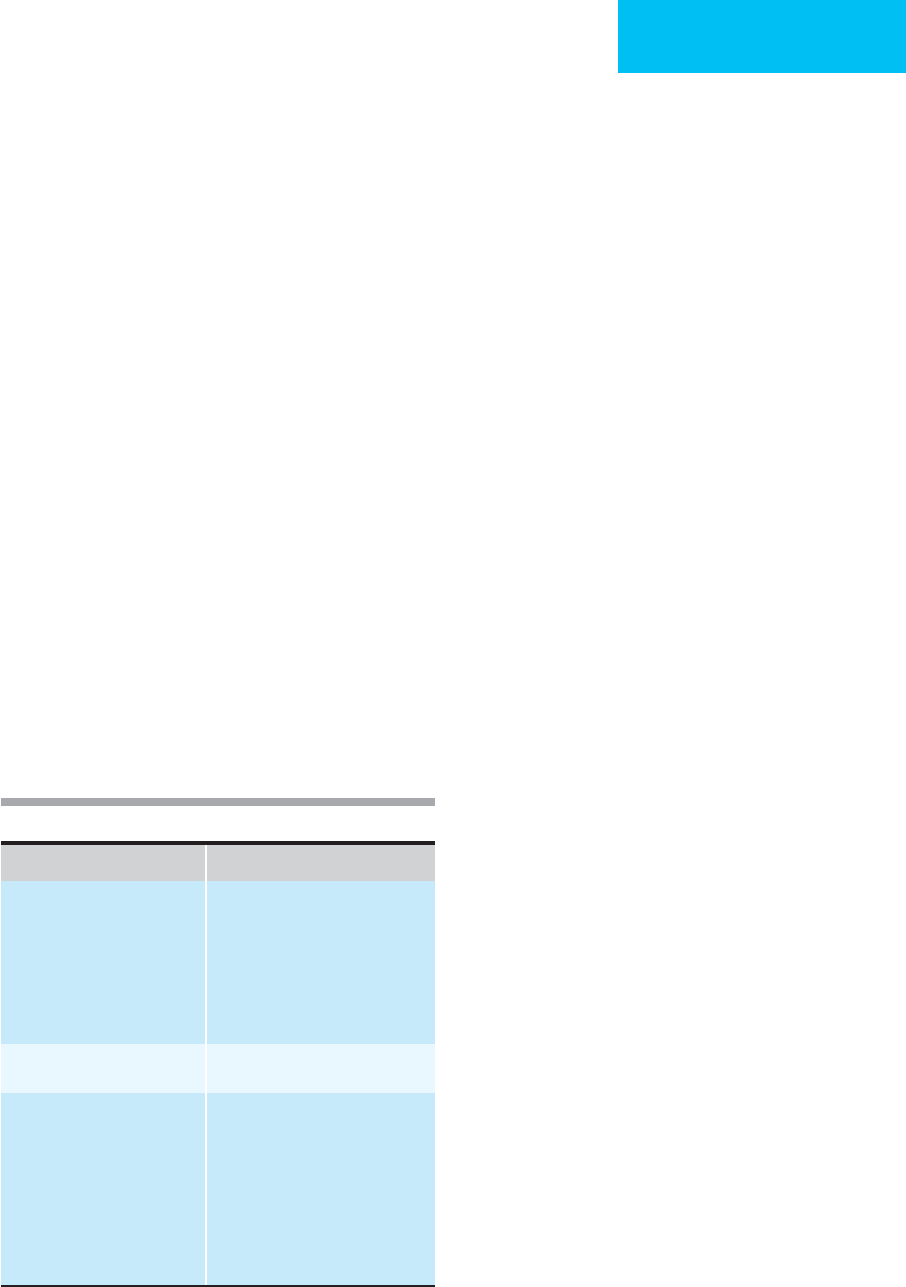

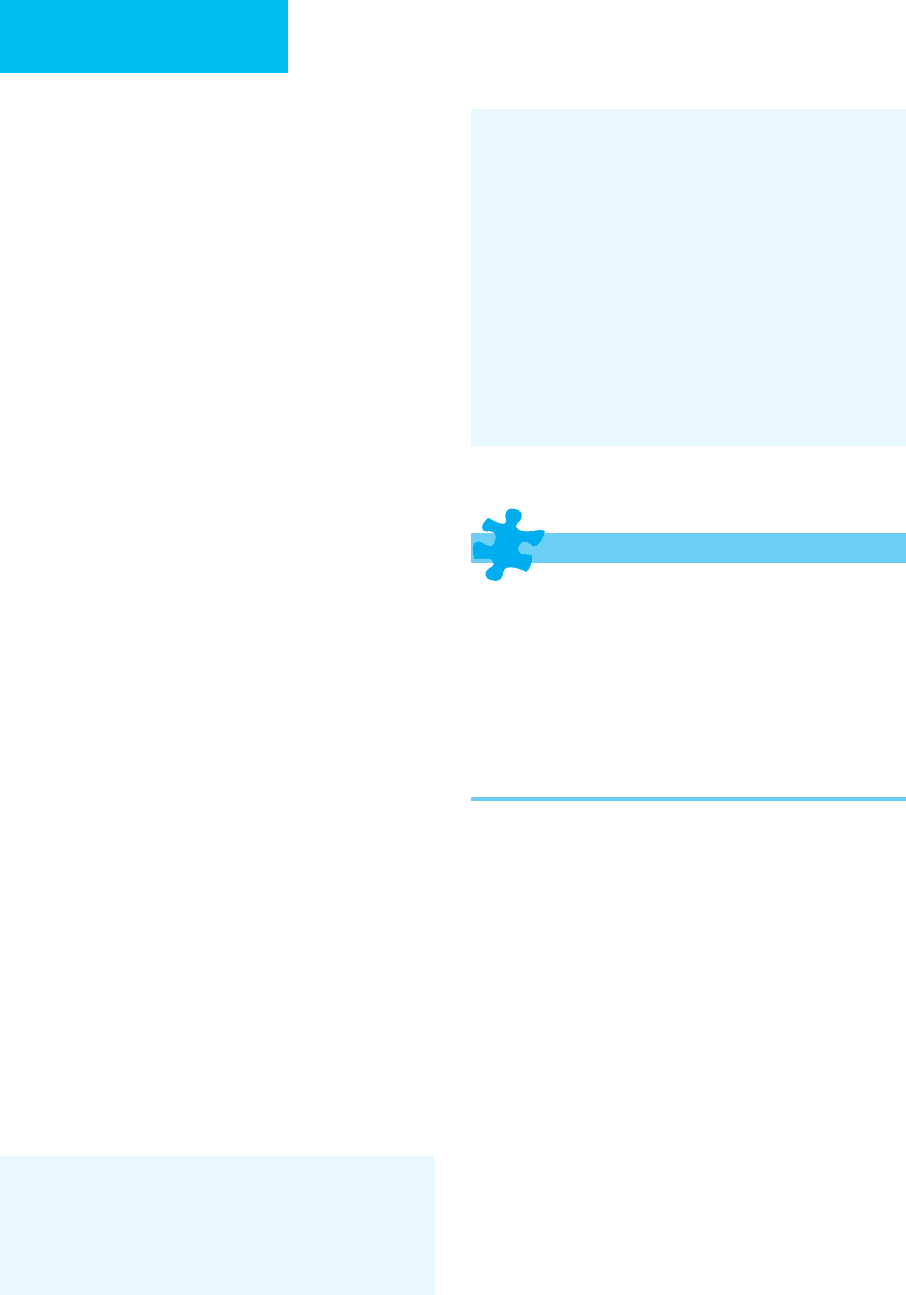

Mechanism of Action Treatment

Thyroid hormone replacement Levothyroxine (T

4

), 500 μg by slow

intravenous infusion, followed by

100–150 μg every 24 hours.

or

T4, 200–300 μg, and triiodothyronine

(T

3

), 25 μg IV; 25 μg of T

3

12 hours

later; and 100 μg of T

4

at

24 hours.

Glucocorticoid Hydrocortisone, 100 mg IV every

8 hours.

Supportive measures Maintain adequate ventilation.

Institute endoctracheal intubation

and mechanical ventilation if

necessary.

Identify and treat the precipitating

event.

Provide fluid and electrolyte

replacement as needed.

Correct core body temperature.

Table 25–2. Treatment of myxedema coma.

CHAPTER 25

572

fluids, electrolytes, and vasopressors may be needed to maintain

blood pressure. Rapid rewarming through the use of heating

blankets is not generally recommended because it may provoke

or worsen peripheral vasodilation and hypotension. However,

in patients with severe hypothermia, thermogenic shivering

mechanisms may become impaired, and these patients may not

be able to raise their body temperatures. Therefore, gradual but

active rewarming may be required in some patients. In most

patients with mild hypothermia, wrapping the patient in blan-

kets in a warm room is sufficient to restore body temperature,

provided that thyroid replacement therapy has been initiated.

Treatment of hypothermia is discussed in Chapter 38. A search

for infection or other precipitating factors should be mounted.

In many instances, empirical antibiotic therapy may be justified.

Because of decreased metabolic rate, many drugs are cleared

more slowly in patients with severe hypothyroidism.

Prognosis

Myxedema coma may be fatal if unrecognized and left

untreated. Poor prognostic indicators include severe hyper-

capnia and hypothermia. If infection or other precipitating

illness is present, outcome depends on treatment and

response to these problems. Complications of thyroxine (T

4

)

and triiodothyronine (T

3

) replacement therapy may include

serious cardiac morbidities, such as acute coronary syn-

drome and cardiac arrhythmias.

Escobar-Morreale HF et al: Thyroid hormone replacement therapy

in primary hypothyroidism: A randomized trial comparing

L

-

thyroxine plus liothyronine with

L

-thyroxine alone. Ann Intern

Med 2005;142:412–24. [PMID: 15767619]

Fliers E, Wiersinga WM: Myxedema coma. Rev Endocr Metab

Disord 2003;4:137–41. [PMID: 12766541]

Goldberg PA, Inzucchi SE: Critical issues in endocrinology. Clin

Chest Med 2003;24:583–606. [PMID: 14710692]

Rodriguez I et al: Factors associated with mortality of patients with

myxoedema coma: Prospective study in 11 cases treated in a sin-

gle institution. J Endocrinol 2004;180:347–50. [PMID: 14765987]

Wartofsky L: Myxedema coma. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am

2006;35:687–98. [PMID: 17127141]

Acute Adrenal Insufficiency

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Hypotension, volume depletion, hypovolemic shock.

Hyperkalemia, hyponatremia.

Weakness, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever.

Acute infectious illness or trauma, recent cessation of

corticosteroid therapy, or inadequate replacement in

chronic adrenal insufficiency.

Abnormal ACTH stimulation test.

General Considerations

Critical illness, whether from sepsis, trauma, surgery, or any

condition associated with hemodynamic compromise, stim-

ulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis causing an

increased production of cortisol. This hormone, synthesized

in the adrenal cortex under the influence of ACTH, main-

tains vascular integrity and tone, stimulates neoglucogenesis

and free water clearance, and influences fluid and electrolyte

balance. Lack of aldosterone—a mineralocorticoid—is asso-

ciated with inability to conserve sodium in the face of hypo-

volemia and hyperkalemia. Deficiency of cortisol—a

glucocorticoid—on the other hand, is associated with inabil-

ity to clear free water and with hemodynamic compromise

mimicking hypovolemic or septic shock. Hyponatremia, a

hallmark of adrenal insufficiency, is typically due to the

inability of these patients to clear free water owing to corti-

sol deficiency and dysregulated antidiuretic hormone (ADH)

secretion. Patients with adrenal insufficiency become

hypotensive owing to a combination of factors, including

hypovolemia and impaired vascular response to cate-

cholamines and also to loss of a direct inotropic effect of cor-

tisol. Cortisol stimulates hepatic neoglucogenesis, and it is

therefore not surprising that patients with adrenal insuffi-

ciency may present with hypoglycemia. Serum cortisol levels

in acutely ill patients are usually increased.

Acute adrenal insufficiency is the result of inadequate

cortisol production with life-threatening cardiovascular col-

lapse and potentially severe electrolyte and fluid abnormali-

ties. Acute insufficiency can occur as a result of an acute

insult to the adrenal glands from infection or trauma or may

be seen in a patient with chronic adrenal insufficiency who

develops critical illness. Patients who receive corticosteroids

for treatment of inflammatory diseases will have chronic

suppression of pituitary-adrenal function, and abrupt cessa-

tion of therapy may precipitate acute adrenal insufficiency,

especially if there is intercurrent illness. A high index of sus-

picion for the diagnosis of adrenal crisis is the key. Because

delay in instituting treatment can be fatal, acute adrenal

insufficiency should be suspected in any patient presenting

with hypotension, fever, abdominal pain, hyponatremia, or

hyperkalemia, especially if hyperpigmentation is present. In

many clinical situations, empirical therapy may be appropri-

ate, even before a definitive diagnosis has been made.

Pathophysiology

Idiopathic or autoimmune adrenalitis accounts for about

80% of cases of chronic adrenal insufficiency in outpatients.

Tuberculosis used to be a major cause of adrenal insuffi-

ciency, but that disease is relatively uncommon now in devel-

oped countries. Other less common causes include adrenal

hemorrhage; fungal infections such as histoplasmosis, coc-

cidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and candidiasis; hemochro-

matosis; irradiation; surgical removal of the adrenal glands;

drug toxicity; and congenital disorders such as synthetic

ENDOCRINE PROBLEMS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

573

enzyme deficiencies. Patients with HIV infection often have

abnormalities in the adrenal glands at autopsy but appear to

have only a slightly increased incidence of adrenal insuffi-

ciency (about 5–10%). The impaired immune status result-

ing from HIV infection increases the likelihood of adrenal

involvement with cytomegalovirus (the most common find-

ing), fungi (eg, Cryptococcus and Histoplasma), or mycobac-

teria (both tuberculous and nontuberculous). HIV, however,

directly affects the adrenal glands only in a small number of

patients. Secondary adrenal insufficiency can occur in HIV-

infected patients because of direct involvement of the hypo-

thalamus or the pituitary gland, opportunistic infections

(eg, tuberculoma or histoplasmosis), or lymphoma.

Other causes of adrenal insufficiency include metastatic

cancer and hemorrhage. Although metastases to the adrenal

gland are relatively common, adrenal insufficiency as a result

of metastatic disease is uncommon. Adrenal hemorrhage may

occur during the course of sepsis, excessive anticoagulation,

trauma, pregnancy, or surgery. Adrenal infarction may occur

as a result of thrombosis, embolism, or arteritis. Infiltrative

disorders include amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and hemochro-

matosis. Congenital disorders leading to adrenal insufficiency

include congenital adrenal hyperplasia. This is due to a genetic

defect in one of the steroidogenic enzymes or hypoplasia.

A number of drugs directly inhibit the enzymes involved in

steroidogenesis. Etomidate is frequently used during endotra-

cheal intubation; it suppresses adrenocortical function for up

to 24 hours. Metyrapone inhibits β-hydroxylase, aminog-

lutethimide inhibits side-chain cleavage enzymes, ketoconazole

inhibits a number of cytochrome P450-linked steroidogenic

enzymes, and mitotane is an adrenolytic cytotoxic agent.

Fluconazole also has been implicated. Relatively common med-

ications such as rifampin and seizure medications (eg, pheny-

toin and carbamazepine) increase hepatic cytochrome P450

activity, thus increasing cortisol metabolism. These medica-

tions should be used with caution in patients with limited adre-

nal reserve.

In patients with autoimmune adrenalitis, there is an

increased incidence of other endocrinopathies. For example,

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, pernicious anemia,

hypoparathyroidism, premature ovarian or testicular failure,

and type 1 diabetes occur with a greater frequency than in

the general population. It is now clear that multiple

endocrine organs may be affected by organ-specific autoim-

mune disease. These polyendocrine autoimmune syndromes

are classified into two major groups: type I and type II. Type

I patients usually present in early childhood with

hypoparathyroidism and mucocutaneous candidiasis; adre-

nal insufficiency may develop later. Disease is usually limited

to one generation of siblings. Genetic analyses of families are

consistent with an autosomal recessive inheritance in a single

gene. Mutations in an autoimmune regulator gene (AIRE)

have been described in association with polyendocrine

autoimmune syndrome type I. In contrast, type II patients

usually present with adrenal insufficiency in the third or

fourth decade. Type 1 diabetes mellitus occurs in almost

half of patients. There is a strong association with HLA-DR3

or -DR4 haplotypes. Hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease),

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, primary ovarian failure, myasthenia

gravis, celiac disease, and pernicious anemia occur much more

commonly in patients with type II polyendocrine autoimmune

syndrome than in the general population. Multiple generations

in the same family are usually affected. The genetic analyses of

families suggest that it is a polygenic disorder with autosomal

dominant inheritance. Autoantibodies against at least three

cytochrome P450 enzymes that are involved in cortisol synthe-

sis have been reported in association with Addison’s disease

as part of both type I and type II syndromes.

Acute Adrenal Crisis

Acute adrenal crisis refers to the collapse and shock syndrome

that occurs in a patient with inadequate adrenal cortical

function. This can occur in chronic adrenal insufficiency

because of stress imposed by a serious illness such as infec-

tion, trauma, or surgery without adequate replacement. In

other patients, acute bilateral adrenal hemorrhage (ie,

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome), originally described in

association with meningococcemia, is the cause of acute adre-

nal insufficiency. Acute adrenal hemorrhage can complicate the

course of systemic sepsis from other pathogens as well. In fact,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common organism in children

dying with sepsis and adrenal hemorrhage. Other common

acute antecedent factors include anticoagulant therapy, dissem-

inated intravascular coagulation, and the perioperative state.

Clinical Features

The clinical manifestations of adrenal insufficiency depend

(1) on whether the patient has primary or secondary adrenal

failure, (2) on the presence or absence of other endocrinopathies

(eg, coexistence of hypothyroidism may significantly attenu-

ate the manifestations of adrenal insufficiency), and (3) on the

presence of superimposed nonendocrinologic illness or stress.

In the ICU, symptoms and signs of the acute illness may

overshadow the features of concomitant adrenal insuffi-

ciency, making clinical suspicion the key to diagnosis.

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with chronic adrenal

insufficiency may not come to medical attention for some

time because of the nonspecific nature of symptoms, such as

fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, and vomiting. Other

manifestations include weakness, salt craving, and postural

dizziness. Patients with primary adrenal insufficiency usually

have hyperpigmentation of the skin and mucous membranes

because of increased ACTH production by the pituitary.

Patients often develop a “tan” in both sun-exposed and non-

exposed parts, especially in areas that suffer chronic friction

and trauma, such as elbows, knees, knuckles, and the belt-

line. The buccal mucosa may show hyperpigmentation,

especially along sites of dental occlusion. The “tan” appear-

ance of these patients often conveys a misleading impression

of good health. Scars acquired during the course of adrenal

CHAPTER 25

574

insufficiency also become hyperpigmented, whereas those

acquired before or after remain unpigmented.

The hallmarks of acute adrenal insufficiency (ie, adrenal

crisis) include severe hypotension and vascular collapse, nau-

sea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever. Hypotension is due

largely to volume depletion, and there may be other evidence

of volume depletion. Abdominal symptoms may lead to an

erroneous diagnosis of acute abdomen, resulting in unwar-

ranted and potentially catastrophic surgical exploration.

Confusion and altered mental status also may occur.

Petechiae may be found if meningococcemia is the cause of

acute adrenal hemorrhage. Hyperpigmentation, if present,

indicates chronic primary adrenal insufficiency. Infection,

surgical stress, and trauma may precipitate acute adrenal cri-

sis in patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency. Patients

should be questioned about receiving chronic corticosteroid

therapy, especially if they have a history of asthma, interstitial

lung disease, rheumatologic diseases such as systemic lupus

erythematosus, or lymphoproliferative disorders. Patients

with HIV infection and autoimmune endocrinopathies

should be suspected of adrenal insufficiency if they present

with intractable hypotension and hyponatremia.

A degree of clinical suspicion may be necessary in evalu-

ating critically ill patients who may present in atypical fash-

ion. Patients with hemodynamic instability that cannot be

explained easily—in association with fever with no identified

source and alteration in mental status—should be consid-

ered for adrenal insufficiency. These patients may benefit

from empirical adrenal replacement therapy.

B. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory data may reveal

hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and azotemia. Hypoglycemia

occurs more often in children but may be seen in adults as

well, especially in those who have been vomiting.

Corticosteroids play an important role in regulating gluco-

neogenesis and have potent anti-insulin actions.

Hypercalcemia and eosinophilia also may be found.

Hyponatremia is usually multifactorial. Patients with pri-

mary adrenal insufficiency are unable to conserve sodium

because of mineralocorticoid deficiency. However, these

patients become hyponatremic even in the face of positive

sodium balance. This is so mainly because of inability to

clear free water due to glucocorticoid deficiency. The exact

pathophysiology of the defect in free water clearance in pri-

mary adrenal insufficiency is not known, but there is lack of

adequate suppression of ADH levels in the face of hypona-

tremia. In addition, glucocorticoids also exert a permissive

effect of ADH directly at the kidney level. In the evaluation

of volume depletion and hyponatremia, low urinary sodium

and fractional excretion of sodium usually reflect volume

depletion; in adrenal insufficiency, however, both urinary

indices may be elevated because of the inability of the kid-

neys to conserve sodium maximally in the absence of cortisol

and aldosterone.

C. Adrenal Function Tests—A patient in whom acute adre-

nal insufficiency is suspected should be treated immediately.

However, diagnosis can be made rapidly and reliably by an

ACTH stimulation test. In addition, a random serum cortisol

level greater than 20 μg/dL makes the diagnosis of adrenal

insufficiency unlikely.

The traditional protocol for the rapid ACTH stimulation

test is as follows: 250 μg cosyntropin (containing amino acids

1–24 of ACTH) is administered intravenously, and plasma

samples are obtained at 0, 30, and 60 minutes for measure-

ment of cortisol. In addition, it is helpful to save contingency

samples for plasma aldosterone measurement. Earlier stud-

ies had suggested that an increment of more than 7 μg/dL

after cosyntropin administration or peak levels greater than

17 μg/dL would exclude adrenal insufficiency. However,

other data indicate that any cortisol value greater than or

equal to 20 μg/dL before or after the cosyntropin test is con-

sistent with normal adrenal function. A normal response

excludes primary adrenal insufficiency. Concern about adre-

nal insufficiency should be raised if any of these criteria are

not met. A small incremental increase in plasma cortisol

after cosyntropin despite a baseline value in the normal

range may be associated with a poor outcome and increased

mortality.

Some studies have suggested that the supraphysiologic

dose of corticotropin used may cause false-negative readings

in patients with partial or secondary adrenal insufficiency.

This is so because patients with adrenal insufficiency may

have some reserves left, and using the relatively large dose of

corticotropin might lead to a normal response. Some have

advocated using instead a low-dose ACTH stimulation test

with 1 μg corticotropin. A normal response is a rise in corti-

sol level to 20 μg/dL or more at 30 or 60 minutes.

If the cortisol response to cosyntropin is subnormal, the

contingency samples can be used to measure aldosterone and

endogenous ACTH to distinguish primary from secondary

adrenal insufficiency. Aldosterone responses to cosyntropin

are impaired in primary adrenal insufficiency but are pre-

served in secondary adrenal insufficiency (due to decreased

endogenous ACTH secretion). ACTH is elevated in primary

adrenal insufficiency and low normal or below normal in

secondary adrenal insufficiency. Certain clinical features also

can be useful in distinguishing primary from secondary

adrenal insufficiency. For example, hyperpigmentation and

hyperkalemia are observed in primary but not in secondary

adrenal insufficiency. The presence of other endocrine hor-

mone deficiencies does not necessarily indicate panhypopi-

tuitarism because these also could be a consequence of

autoimmune polyendocrinopathy.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency has been made,

treatment is relatively straightforward (Table 25–3).

A. Corticosteroid Replacement—Promptness in institut-

ing corticosteroid therapy is very important. Corticosteroid

replacement can be given as hydrocortisone sodium succinate,

75–100 mg intravenously every 6–8 hours. If the patient is

ENDOCRINE PROBLEMS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

575

hypotensive, performance of the diagnostic ACTH stimula-

tion test may unduly delay institution of therapy. Under

these circumstances, an equivalent dose of dexamethasone

(3–4 mg every 6–8 hours) can be given intravenously con-

temporaneously with ACTH administration. Dexamethasone

does not crossreact in the cortisol assay, and the diagnostic

procedure therefore can be done without concern about the

delay in instituting replacement therapy. The dose of hydro-

cortisone sodium succinate can be reduced to the replace-

ment level (10–20 mg in the morning and 5–10 mg in the

evening) as the patient’s condition improves.

Some studies cast doubt on the need for large pharmaco-

logic doses of corticosteroids during surgery. Studies in

adrenalectomized monkeys suggest that physiologic replace-

ment doses of corticosteroids are sufficient in this primate

model to tolerate the stress of surgical laparotomy.

Supraphysiologic doses of corticosteroids conferred no sur-

vival advantage on these adrenalectomized monkeys over

physiologic replacement doses during the period of surgical

stress. Other studies have shown that patients receiving

steroids prior to undergoing surgery did not require addi-

tional glucocorticoids during the perioperative period.

Empirical recommendations for glucocorticoid adminis-

tration in surgical patients are to estimate the degree of stress

and give 25 mg/day of hydrocortisone for mild stress, 50–75

mg/day for 2–3 days for moderate stress, and 100–150

mg/day for 2–3 days for severe stress. After recovery from

acute illness, patients with adrenal insufficiency should be

placed on chronic replacement therapy with hydrocortisone.

Traditionally, a dose of 30 mg hydrocortisone administered

in two divided doses—20 mg in the morning and 10 mg in

the evening—has been used widely. However, recent assess-

ments using more accurate isotope dilution and mass spec-

trometric methods suggest that daily cortisol production

rates are 5–6 mg/m

2

of body surface area rather than the

12–15 mg/m

2

of body surface area, as was thought previously.

Therefore, the traditional regimen of 30 mg hydrocortisone

daily possibly represents excessive glucocorticoid replace-

ment and may increase the risk of osteoporosis. A more

appropriate regimen may be 15 mg hydrocortisone adminis-

tered in two divided doses: 10 mg in the morning and 5 mg

in the afternoon. Although hydrocortisone traditionally has

been administered in a twice-daily regimen, some authors

have suggested that a thrice-daily regimen (10, 5, and 5 mg)

might provide more physiologic cortisol levels.

B. Mineralocorticoid Replacement—Most patients with

primary adrenal insufficiency require mineralocorticoid

replacement. In chronic adrenal insufficiency, this can be

administered as fludrocortisone acetate. The usual starting

dosage is 0.05–0.1 mg by mouth daily. Some patients may

develop leg edema on initiation of therapy. This usually will

abate if the dose is reduced. Hydrocortisone by itself has

some mineralocorticoid activity, so when patients are receiv-

ing more than 50–60 mg/day of hydrocortisone, no addi-

tional mineralocorticoid replacement is necessary. However,

if dexamethasone, which has little or no mineralocorticoid

activity, is used instead of hydrocortisone, a mineralocorti-

coid should be added.

C. Fluid and Electrolytes—Patients with adrenal insuffi-

ciency often have an enormous salt and water deficit. It is

important to correct these deficits aggressively by adminis-

tration of 0.9% NaCl solution intravenously. However,

patients with adrenal insufficiency may continue to be

hypotensive even after adequate fluid and electrolyte

replacement. Blood pressure may be restored only by cor-

ticosteroid administration. It is often not recognized that

corticosteroids have an inotropic effect on the myocardium.

Patients with adrenal insufficiency may present with

hyperkalemia; therefore, routine potassium replacement

should be postponed until serum potassium measure-

ments are obtained.

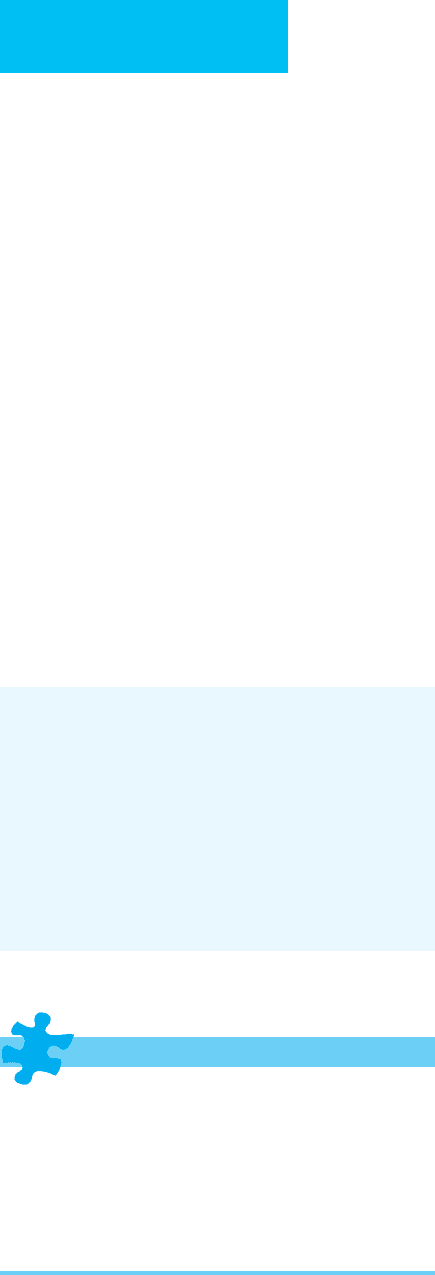

Diagnostic testing If you are considering a diagnosis of acute adrenal insufficiency, perform a rapid ACTH test (see text) immediately and initiate

treatment pending return of laboratory results. If a patient is highly likely to have adrenal insufficiency, give dexamethasone

immediately while the ACTH test is being conducted.

Glucocorticoid Hydrocortisone sodium succinate, 75–100 mg IV immediately and then every 6–8 hours.

or

Dexamethasone, 3–4 mg IV every 6–8 hours.

Mineralocorticoid Not required when large doses of hydrocortisone (>50–60 mg/d) are used. Consider adding fludrocortisone acetate, 0.05–0.1 mg

orally daily if dexamethasone is used.

Supportive measures Identify and treat the precipitating illness.

Correct fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. Intravenous NaCl 0.9% is usually given initially.

Monitor blood glucose and electrolytes and administer glucose if necessary.

Table 25–3. Management of acute adrenal insufficiency (adrenal crisis).

CHAPTER 25

576

D. Glucose—Corticosteroids are important regulators of

gluconeogenesis. Although in adults, unlike children, hypo-

glycemia is not a common manifestation of adrenal insuffi-

ciency, patients who have been vomiting for a few days may

present with hypoglycemia or develop hypoglycemia during

the course of evaluation or treatment. Therefore, plasma glu-

cose levels should be monitored and glucose given intra-

venously to correct or prevent hypoglycemia.

E. Other Treatment—It is crucial to identify and treat the

antecedent illness precipitating acute adrenal insufficiency.

This may include administration of antibiotics to treat an

infection. Many patients with adrenal insufficiency have one

or more endocrinopathies. It is important to recognize and

treat these when identified.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Serum cortisol is measured as the total rather than free cor-

tisol, and more than 90% of cortisol is protein-bound. In

critically ill patients, low serum albumin and serum proteins

may cause lower serum total cortisol but normal free corti-

sol. Therefore, some patients might be labeled incorrectly as

having cortisol deficiency. In a recently published study,

baseline and postcosyntropin total cortisol were lower in

patients with serum albumin levels of less than 2.5 g/dL com-

pared with those with higher serum albumin levels. Despite

this finding, baseline and postcosyntropin free cortisol meas-

urements were often not different. Thus, in this study, almost

40% of patients with low serum albumin levels had low total

cortisol levels, but all had normal adrenal function. Because

free cortisol measurements are not widely available, it is not

clear how to interpret low serum total cortisol in the face of

hypoproteinemia. The safest course would be to continue to

give these patients glucocorticoid replacement but recognize

that some of the patients may be treated unnecessarily.

Another controversial issue has been the use of corticos-

teroids in patients with septic shock. Some studies suggest

that hydrocortisone at dosages similar to replacement for

adrenal insufficiency improves outcome in septic shock.

Benefit was seen almost exclusively in those with an increase

in serum cortisol level of less than 9 μg/dL in response to cor-

ticotropin, despite some patients having supraphysiologic

baseline serum cortisol levels. A cytokine-induced “relative”

adrenal insufficiency has been postulated, but it is not clear

that patients with high cortisol levels require replacement.

However, a recent study did not find that corticosteroids

benefit septic shock patients, and one recommendation is to

use corticosteroids only if baseline cortisol levels are very low

or if etomidate had been given within 24 hours.

Alonso N et al: Evaluation of two replacement regimens in primary

adrenal insufficiency patients: Effects on clinical symptoms,

health-related quality of life and biochemical parameters.

J Endocr Invest 2004;27:449–54. [PMID: 15279078]

Annane D et al: Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency in severe sepsis

and septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:1319–26.

[PMID: 16973979]

Cooper MS, Stewart PM: Corticosteroid insufficiency in acutely ill

patients. N Engl J Med 2003;348:727–3. [PMID: 12594318]

Dittmar M, Kahaly GJ: Polyglandular autoimmune syndromes:

Immunogenetics and long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 2005;88:2983–92. [PMID: 12843130]

Hamrahian AH, Oseni TS, Arafah BM: Measurements of serum

free cortisol in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2004;350:

1629–38. [PMID: 15084695]

Ho JT et al: Septic shock and sepsis: A comparison of total and free

plasma cortisol levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:105–14.

[PMID: 16263835]

Minneci PC et al: Meta-analysis: The effect of steroids on survival

and shock during sepsis depends on the dose. Ann Intern Med

2004;141:47–56. [PMID: 15238370]

Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for

patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med 2008;358:111–24.

[PMID: 18184957]

Sick Euthyroid Syndrome

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Low T

3

and/or low total T

4

suggestive of hypothy-

roidism in a patient with acute or chronic nonthyroidal

illness.

But patient is euthyroid, as shown by clinical appear-

ance, normal TSH, usually normal TSH response to

thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), and normal free

T

4

by equilibrium dialysis.

In extremely ill patients, free T

4

may fall to subnormal

levels.

General Considerations

Alterations in thyroid function occurring with nonthyroidal

illness are usually associated with changes in other hormonal

systems and can be thought of as part of a complex and mul-

tifaceted response of the endocrine system to illness. A num-

ber of nonthyroidal illnesses produce alterations in thyroid

function in patients in whom no intrinsic thyroid disease is

present and the patient is judged to be euthyroid. These low

T

3

and low T

3

-T

4

syndromes seen with nonthyroidal illness

represent a continuum probably reflecting severity of the dis-

ease process rather than discrete conditions. The syndromes

must be distinguished from hypothyroidism because their

treatment requires correction of the underlying disorder

rather than thyroid hormone replacement.

Pathophysiology

The sick euthyroid syndrome is essentially a laboratory diag-

nosis (Table 25–4). Patients are clinically euthyroid, but

because they have acute or chronic nonthyroidal illness, the

underlying disease may make assessment of thyroid status

difficult or unclear. The syndrome may be divided into three