Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PULMONARY DISEASE

557

when used in the setting of venous thromboembolism.

Bleeding is usually not spontaneous but due to some underly-

ing cause. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia may con-

tribute to bleeding, as may simultaneous administration of

antiplatelet agents such as aspirin or dextran. Warfarin and

other oral anticoagulant agents are also associated with bleed-

ing complications. Bleeding has been demonstrated to be less

common when excessively prolonged coagulation times are

avoided.

The effect of UFH can be quickly counteracted by discon-

tinuing its infusion and administering protamine sulfate.

Approximately 1 mg of protamine will neutralize 100 units of

circulating heparin. The reversal of subcutaneously adminis-

tered UFH may require a prolonged infusion of protamine.

Patients who use a protamine-based insulin preparation, have

undergone a vasectomy, or have known hypersensitivity to fish

are at increased risk of developing adverse allergic reactions to

protamine, including anaphylaxis. The effects of LMWH are

only in part reversed by the administration of protamine.

Nonbleeding patients on warfarin with an elevated INR but

in the less than 5.0 range can safely have warfarin withheld

until the INR falls into the therapeutic range. For INR values

between 5.0 and 9.0, low-dose vitamin K (<5 mg oral phy-

tonadione) is indicated if there is bleeding, high risk of bleed-

ing, or need for performing an invasive procedure. If the INR

is greater than 9.0 and associated with bleeding, oral vitamin

K in larger doses (5–10 mg) is necessary. For serious bleeding

at any elevation of INR, treatment is a 10 mg slow intra-

venous infusion of vitamin K supplemented with factor

replacement (eg, fresh-frozen plasma or prothrombin com-

plex concentrate). Restoration of the desired anticoagulated

state may be difficult and prolonged if too much vitamin K is

administered. Reversal of the effects of warfarin with oral or

intravenous vitamin K can take several hours to correct the

INR, whereas fresh-frozen plasma, which contains the vitamin

K–dependent factors inhibited by warfarin, can be given to

reverse the prothrombin time relatively quickly.

An important complication of heparin use is heparin-

induced thrombocytopenia syndrome, an immune-mediated

disease that is associated with both bleeding and venous and

arterial thrombotic complications. This syndrome should be

suspected when the platelet count falls precipitously in a

patient receiving any form of heparin. It is seen in approxi-

mately 3–4% of patients receiving UFH and fewer patients

receiving LMWH. Treatment of this syndrome includes

immediate discontinuation of all forms of heparin adminis-

tration, including intravenous flushes. If anticoagulation is

still necessary for the patient’s primary disease process, direct

thrombin inhibitors (eg, lepirudin, bivalirudin, and arga-

troban) or heparinoids (eg, danaparoid) can be used. Case

reports of using fondaparinux, a synthetic pentasaccharide

anticoagulant, in cases of heparin-induced thrombocytope-

nia are also in the literature. However, this drug is not currently

FDA approved for this indication, but may play a role in the

future as more evidence becomes available. Warfarin should

not be used alone.

B. Thrombolytic Therapy—Thrombolytic agents currently

approved for use in venous thromboembolic disease in the

United States are urokinase, streptokinase, and alteplase (ie,

recombinant tissue plasminogen activator [tPA]). Deep

venous thrombosis, especially in patients with extensive

iliofemoral thrombosis with limb threat owing to vascular

occlusion, is an approved indication for the use of throm-

bolytic agents according to the 2004 American College of

Chest Physician guidelines. In studies in which thrombolytic

therapy was given for pulmonary embolism the associated

deep vein thrombosis resolved more rapidly, and there was

evidence that destruction of venous valves was lessened,

decreasing the pain, swelling, and potential for postphlebitic

venous insufficiency. However, thrombolytic therapy should

be individualized and is not currently recommended as rou-

tine therapy for deep vein thrombosis.

In short-term studies of pulmonary embolism, throm-

bolytic therapy was associated with faster clot lysis than

heparin, decreased pulmonary hypertension, improved pul-

monary perfusion, and subsequent higher pulmonary capil-

lary blood volume, as assessed by carbon monoxide diffusing

capacity. A trend toward lower death rates in patients with pul-

monary embolism treated with urokinase followed by heparin

compared with those given heparin alone was seen in one trial;

in the first 2 weeks of treatment, 7% died in the urokinase

group compared with 9% in the heparin group. Lower num-

bers of recurrent pulmonary emboli in the urokinase-treated

group also were found. Despite these results, many physicians

believe that the benefits of thrombolytic therapy over antico-

agulation alone are not clear for patients with pulmonary

embolism. Thus the vast majority of patients are treated with

heparin and oral anticoagulation alone.

Thrombolytic therapy has been considered most often in

the setting of “massive”pulmonary embolism, described in ear-

lier studies based on the radiographic finding of a clot occupy-

ing over 50% of the pulmonary vascular bed. Occlusion of

much smaller amount of the pulmonary vascular bed may be

considered “massive” in a patient with significant underlying

cardiopulmonary disease. Rather than the size of the radio-

graphic occlusion itself defining a massive pulmonary

embolism, this syndrome is now defined by the presence of

severe hemodynamic compromise with hypotension, shock,

syncope, or severe gas-exchange abnormalities. Several small

clinical trials of patients with severe large pulmonary emboli

have shown faster lysis of clot in the pulmonary circulation,

reduction of pulmonary artery pressure, and improved cardiac

output with the combination of thrombolytic agent and

heparin compared with heparin alone. However, a survival

benefit has not been clearly established with this therapy and

the risk of bleeding is higher than when heparin is used alone.

At present, thrombolytic therapy should be considered in

patients with acute massive embolism who are hemodynami-

cally unstable and who appear to be able to tolerate throm-

bolysis. It may also be a consideration in patients with

“submassive” embolism who show evidence of right ventric-

ular (RV) dysfunction, but this area remains controversial.

CHAPTER 24

558

RV dysfunction appears to identify normotensive patients

who have a significantly higher risk of recurrent pulmonary

embolism and death, and therefore, thrombolysis may bene-

fit this subgroup of patients. Mortality rates between 4.3%

and 12.8% have been seen in patients with an acute pul-

monary embolism with evidence of RV dysfunction as com-

pared with rates between 0% and 0.9% in patients with

normal right-sided heart function. Echocardiography has

become a key tool used to evaluate right-sided heart function

in these patients. Echocardiographic findings suggestive of

RV dysfunction acutely related to a pulmonary embolism

include qualitative findings such as RV hypokinesis and

quantitative finding such as enlarged RV to LV end-diastolic

diameter greater than 1 mm, RV end-diastolic diameter

greater than 30 mm, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure

greater than 30 mm Hg. Another echocardiographic finding

that has been found to have a high specificity in the diagnosis

of an acute pulmonary embolism is the McConnell sign in

which the RV fee wall is hypokinetic in the face of preserved

contractility of the apical segment.

Most investigators previously recommended that pul-

monary angiography be used to confirm the diagnosis of

pulmonary embolism prior to the administration of throm-

bolytic therapy. However, one analysis found that the fre-

quency of major bleeding averaged 14% in patients who

received tissue plasminogen activator after pulmonary

angiography, whereas it was estimated from thrombolytic

trials in acute myocardial infarction patients that a noninva-

sive diagnosis of pulmonary embolism would be associated

with only a 4.2% risk of bleeding. These authors suggested

that it would be safer to avoid pulmonary angiography for

patients chosen to receive thrombolytics who have positive

findings on a CT pulmonary angiogram, a high-probability

lung scan, an intermediate-probability scan plus high clinical

suspicion, or evidence of significant RV dysfunction by

echocardiography. A comparison of relative risks may prove

useful in making decisions about pulmonary angiography

and thrombolytic therapy.

Contraindications to thrombolytic therapy include sur-

gery in the past 10 days, recent puncture or invasion of non-

compressible vessels, recent intracerebral hemorrhage or

stroke, uncontrolled hypertension, recent trauma, preg-

nancy, hemorrhagic retinopathy, other sites of potential

bleeding, and infective endocarditis. In addition, streptoki-

nase has been associated with allergic reactions given its anti-

genic properties and cannot be administered more than once

in a 6-month period. Customary invasive vascular proce-

dures such as arterial blood gas measurements and catheter-

ization sites where bleeding cannot be easily controlled

should be avoided. Pulmonary angiography, if done, should

be approached from the brachial vein rather than from the

femoral vein. Heparin should be discontinued before starting

thrombolytic agents; antiplatelet agents should not be given

simultaneously.

Streptokinase, urokinase, and alteplase have been used

in pulmonary embolism. Urokinase and streptokinase are

given as a loading dose (streptokinase: 250,000 units over

30 minutes; urokinase: 4400 units/kg over 10 minutes), followed

by continuous infusion (streptokinase: 100,000 units/h for

24 hours; urokinase: 4400 units/kg per hour for 12–24

hours). Alteplase usually has been administered as a contin-

uous peripheral infusion of 100 mg over 2 hours.

After completion of thrombolytic therapy with any of

these agents, the continuous infusion of heparin is reinsti-

tuted once the measured aPTT is less than 2.5 times control.

Streptokinase and urokinase activate plasminogen bound to

both fibrinogen and fibrin, but alteplase or tissue plasmino-

gen activator, a genetic recombinant product, is somewhat

more specific for activation of plasminogen bound to fibrin.

This difference suggestes that alteplase may be associated

with fewer bleeding complications than urokinase or strep-

tokinase, but clinical bleeding so far has been found to be

similar for all three agents.

C. Inferior Vena Cava Interruption—There are no data

supporting the routine use of inferior vena cava (IVC) inter-

ruption with a filter in patients with deep venous thrombosis

or pulmonary emboli. A study comparing anticoagulation

with anticoagulation plus placement of an IVC filter demon-

strated a slight reduction in early symptomatic or asympto-

matic pulmonary embolism. There was no effect on

mortality. After 3 years, a significant increase in recurrent

deep venous thrombosis was found in the IVC filter group.

These data, however, support the effectiveness of IVC

interruption in reducing early embolization. Therefore, three

main indications have evolved for interruption of the infe-

rior vena cava in patients with deep venous thrombosis and

pulmonary embolism. First, patients who are at high risk for

pulmonary embolism (proximal deep venous thrombosis) in

whom heparin is contraindicated should be strongly consid-

ered for the procedure. The contraindication may be a strong

likelihood of bleeding prior to anticoagulation or moderate

to severe bleeding during heparin therapy. For example, in

trauma patients admitted to the ICU who were treated for

deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism with

heparin, 36% developed complications requiring termina-

tion of the drug, whereas no serious complications or deaths

were reported in 34 other patients who underwent place-

ment of an IVC filter. A second indication is failure of anti-

coagulation to prevent recurrent pulmonary embolism

despite an adequate dose and duration of therapy. However,

early embolism after initiation of heparin generally should

not be considered as necessitating IVC interruption because

poorly organized thrombi may detach themselves from the

venous wall or from other parts of the clot regardless of

heparin therapy. Finally, a clinical indication for IVC inter-

ruption is identified in the rare patient whose cardiac and

pulmonary reserves are so low that even a single small pul-

monary thromboembolus may be life-threatening.

The decision to proceed with interruption of the IVC

should be based on evidence that the thromboemboli are

coming from deep veins that flow into that vessel. The right

PULMONARY DISEASE

559

atrium and ventricle and the upper extremities should be

excluded as sources. If an upper extremity is identified as the

continued source of emboli, some centers are capable of

placing superior vena cava filters. Contrast venography or

other proof of existing clot below the site of planned inter-

ruption should be obtained.

The Greenfield filter or other types of intravenous

devices is used most often, while surgical ligation of the IVC

is rarely needed. The filter can be placed via percutaneous

venous access under fluoroscopic guidance either from an

internal jugular vein or from a femoral vein. The filter usu-

ally is positioned below the level of the renal veins, but there

are reports of its being placed above the renal veins in

patients with IVC and renal vein thrombosis. If the filter is

placed because of recurrent pulmonary emboli during anti-

coagulation, anticoagulation usually is continued to prevent

additional thrombi from forming on the filter and else-

where. If the filter is placed because of a contraindication

for or adverse reaction to anticoagulation, anticoagulation

therapy is not given. The risk of recurrent pulmonary

emboli after interruption of the vena cava with this device

is low (2–3%). Other reported problems include procedural

complications, filter malposition and migration, caval

occlusion, and sepsis owing to device infection.

D. Other Treatment—In some centers, emergent pul-

monary embolectomy can be performed in selected patients.

Mortality is high (up to 30% in some series), and special

experience and expertise are needed. Other modalities cur-

rently being investigated include local instillation of throm-

bolytics directly into the embolus; intravascular catheter

disruption systems, including fragmentation, rotor devices,

and rheolytic therapy that break the clot into smaller pieces

that then can be removed; suction catheter removal of the

clot; and balloon angioplasty of the embolus.

E. Supportive Care—Abnormal pulmonary gas exchange

may require supplemental oxygen. Severe respiratory dis-

tress, because of involvement of large portions of the lungs

or because of underlying heart or lung disease, may necessi-

tate mechanical ventilatory support. Some patients may have

bronchospasm that benefits from bronchodilators.

Hemodynamic compromise in pulmonary embolism usually

indicates severe obstruction of the pulmonary circulation

with failure of the right ventricle. Volume loading of the right

ventricle may be helpful. However, volume overexpansion

can lead to increasing right ventricular myocardial oxygen

consumption and subsequent ischemia and deterioration of

function. Inotropic and vasoactive drugs generally are of

little value in severe hemodynamic compromise, but

dopamine, dobutamine, and norepinephrine may be tried.

Prevention

Prevention of deep venous thrombosis and thereby of pul-

monary embolism has become a major goal in the manage-

ment of critically ill patients who are at high risk of

development of deep venous thrombosis as a consequence of

bed rest, immobility, central venous catheterization, critical

illness, or trauma. It has been pointed out, however, that

many ICU patients are not receiving thromboembolism pro-

phylaxis despite this high risk.

The risk of developing a deep vein thrombosis varies with

the clinical scenario and the patient’s underlying medical

condition. Patients with hip fracture, total hip replacement,

or total knee replacement have a 40–70% chance of develop-

ing deep venous thrombosis. Other surgical and medical

patients have approximately a 15–50% risk. It is estimated

that patients with myocardial infarction have about a 24%

overall incidence of deep venous thrombosis, and patients

with stroke may have up to a 55% risk.

Prevention of deep venous thrombosis depends on rever-

sal of predisposing conditions (eg, the local hypercoagulable

state and venous stasis). Antithrombotic therapy can interfere

with thrombus formation either by preventing the platelet

nidus from forming or by preventing activation of the coagu-

lation cascade. The type of preventive therapy is closely linked

to the underlying condition and the bleeding risk. For exam-

ple, patients at moderate risk (eg, minor surgery with additional

risk factors or aged 40 to 60 years with no additional risks)

will benefit from low-dose UFH, LMWH, or intermittent

pneumatic compression of the legs. On the other hand, high-

risk patients including hip fracture or total knee replacement

patients must be treated with LMWH, fondapariunux (2.5

mg started 6–8 hours after surgery), or adjusted-dose war-

farin with a target INR of 2.5. A summary of recommenda-

tions is presented in Table 24–9.

Low-dose UFH, 5000–7500 units subcutaneously every

8–12 hours, has been shown to be effective and safe in several

groups of patients, including those immediately postopera-

tive from general or gynecologic surgery and medical

patients with heart failure, myocardial infarction, respiratory

failure, and stroke. At these doses, the aPTT is not usually

prolonged, and there is little increased risk of bleeding.

LMWH also has been shown to have reliably favorable dose-

response properties and turns out to be superior for prophy-

laxis of deep venous thrombosis in a number of clinical

settings. Warfarin is effective in certain clinical situations

and, for example, is one of the choices for prophylactic treat-

ment for patients with hip fractures as well as elective hip

and knee replacement surgeries. Fondaparinux, a synthetic

pentasaccharide that selectively inhibits factor Xa activity,

has been shown to be highly efficacious in the prevention of

deep vein thrombosis primarily in large orthopedic surgical

trials. Finally, mechanical methods of prophylaxis with grad-

uated compression stockings or external compression of the

legs can be provided by rhythmic intermittent pneumatic

compression devices and have been shown to have compara-

ble effectiveness in preventing deep venous thrombosis with

no risk of hemorrhage. These devices can be combined with

pharmacologic means of prophylaxis in very high-risk

patients or used alone in patients at risk of bleeding compli-

cations from medical therapy.

CHAPTER 24

560

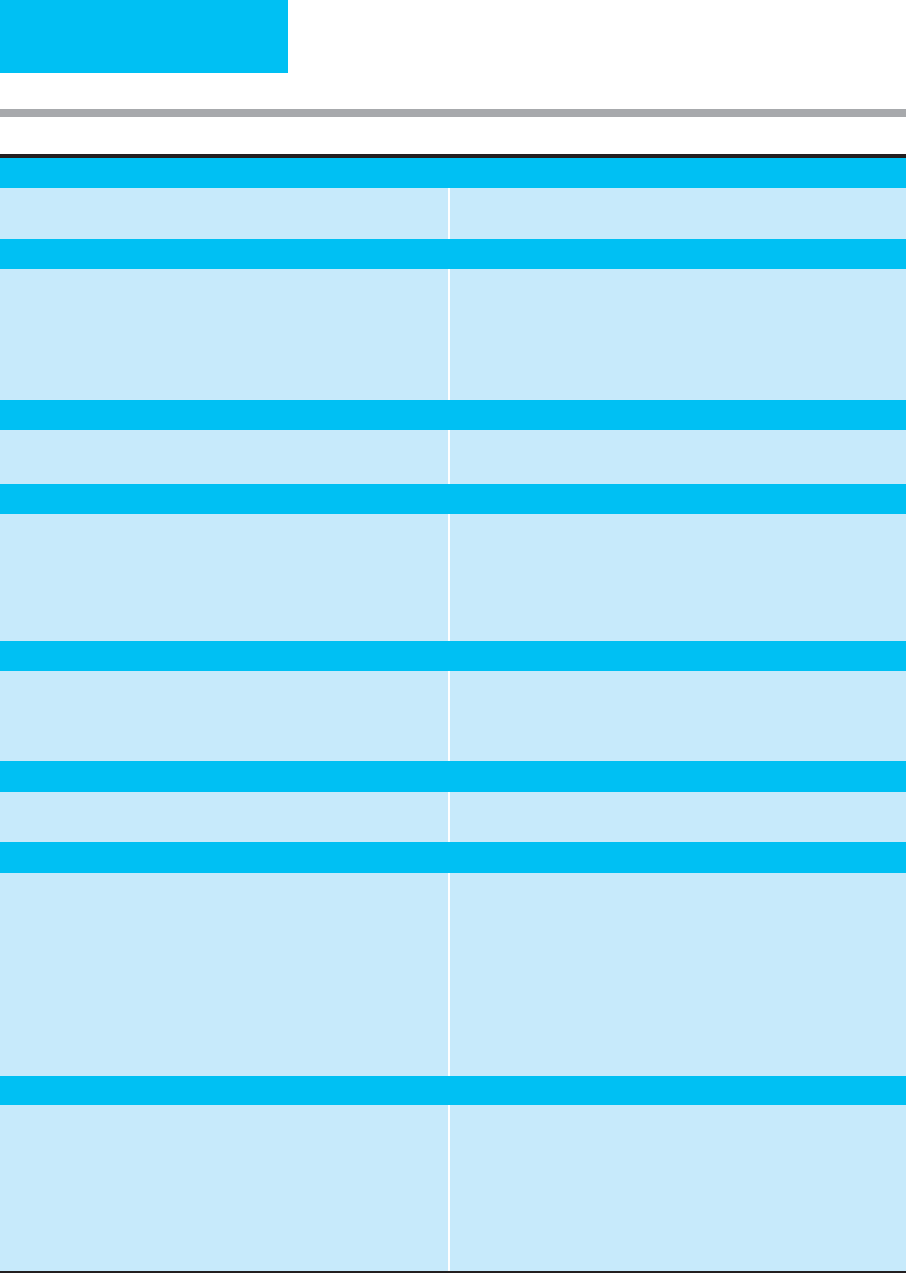

Medical Conditions

Critically ill patients with high bleeding risk

Critically ill patients without high bleeding risk

Mechanical prophylaxis (ES or IPC) until risk diminishes

LDUH or LMWH with or without mechanical prophylaxis

General Surgery

Low risk (minor procedure, age <40, no risk factors)

Moderate risk (40–60 years, major procedure and <40 years

with no risk factors)

High risk (not low or moderate risk) and highest risk (multiple

risk factors)

High risk of bleeding

Early and persistent ambulation

LDUH, 5000 units bid or LMWH <3400 units once/day

LDUH, 5000 units tid or LMWH >3400 units once/day or LMWH with

mechanical prophylaxis (higher risk)

Mechanical prophylaxis (ES or IPC) until risk diminishes

Vascular Surgery

Low-risk procedure

High-risk procedure

No routine prophylaxis

LDUH or LMWH

Gynecologic Surgery

Procedure <30 min for benign disease

Laparoscopic procedure, risk factors present

Major surgery for benign disease

Extensive surgery for malignancy

Early and persistent ambulation

LDUH, LMWH, and/or mechanical prophylaxis

LDUH, 5000 units bid; LDUH, 5000 units tid if VTE risk factors; continue

until discharge; if age >60, continue for 2–4 weeks after discharge

LDUH 5000 units tid or LMWH >3400 units/day; continue for 2–4 weeks

after discharge

Urologic Surgery

Minor, transurethral procedure

Major open procedure

Bleeding or high risk of bleeding

Early and persistent ambulation

LDUH twice or three times daily; with multiple risk factors, add

mechanical prophylaxis

Mechanical prophylaxis (ES or IPC) until risk diminishes

Laparoscopic Surgery

Laparoscopic surgery Early and persistent ambulation, unless risk factors present, then LDUH,

LWMH, and/or mechanical prophylaxis

Orthopedic Surgery

Elective total hip replacement

Elective total knee replacement

Hip fracture surgery

LMWH at high-risk dose, 12 h before surgery or 12–24 h after surgery, or

4–6 h after surgery at half the high-risk dose; increase to high-risk dose

the next day

or

fondaparinux 2.5 mg beginning 6–8 h after surgery

or

adjusted-dose warfarin started the evening after surgery (INR target 2.5)

Continue prophylaxis for 28–35 days after surgery

LMWH at high-risk dose, fondaparinux, or adjusted-dose warfarin (INR

target 2.5)

Fondaparinux, LMWH at high-risk dose, adjusted-dose warfarin (INR target

2.5), or LDUH; continue for 28–35 days after surgery

Table 24–9. Prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism for patients.

Neurosurgery, Trauma, Spinal Cord Injury

Elective spine procedure (elderly, malignancy, neurologic deficit, prior

to VTE, or anterior surgical approach)

Trauma, identifiable risk factor

Acute spinal cord injury

Postoperative LDUH, LMWH, or IPC alone; if multiple risk factors, combine

LDUH or LMWH with mechanical prophylaxis

LMWH, when safe; mechanical prophylaxis if LMWH is delayed or

contraindicated because of high bleeding risk; consider screening with

ultrasound for those at highest risk; continue LMWH or warfarin (INR

target 2.5) after discharge if impaired mobility

Mechanical prophylaxis; add LDUH or LWMH started when safe (hemostasis

achieved)

PULMONARY DISEASE

561

However, in patients with trauma—especially to the brain

or spinal cord—or those undergoing surgical procedures of

the eye, brain, or spinal cord, even low-dose heparin may be

contraindicated because of the increased risk of bleeding at

these operative sites. External pneumatic compression of the

legs is effective in these patients. Neurosurgical patients and

patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia also

should be considered for prevention of deep venous throm-

bosis by pneumatic compression devices. This therapy gener-

ally is well tolerated, but patients may require sedation owing

to discomfort from the cyclic compression or heat generated

by the apparatus.

Hip fractures, major orthopedic surgery, and some types

of urologic surgery enhance the thrombogenic state, prob-

ably by increased contact with and release of tissue throm-

boplastin. While low-dose UFH does decrease the risk of

deep venous thrombosis in some of these patients, it is less

effective than LMWH and the newer anticoagulant fonda-

parinux. Current guidelines recommend the use of LMWH,

fondaparinux, or adjusted-dose warfarin (goal INR 2.5) in

these high-risk orthopedic patients. Adjunctive prophylaxis

with mechanical devices such as elastic stockings and inter-

mittent pneumatic compression devices can add additional

benefit with little risk. The duration of prophylaxis, espe-

cially in this orthopedic patient population, is being inves-

tigated. There is some evidence that extending the period of

prophylaxis to 28–35 days postoperatively has reduced the

incidence of deep venous thrombosis and subsequent pul-

monary embolism. The 2004 ACCP consensus guidelines

recommend extending prophylaxis into the outpatient set-

ting with LMWH, fondaparinux, or warfarin for a total of

4–5 weeks after surgery for these high-risk postoperative

patients.

IVC filters also have been studied for their use in the pre-

vention of complications from deep venous thrombosis, pri-

marily in the surgical population. Four studies evaluating

high-risk surgical patients without current evidence of deep

venous thrombosis using historical controls found a decreased

incidence of pulmonary emboli in the following patients who

had an IVC filter placed: those with high injury severity scores,

head or spinal cord trauma, pelvic or lower extremity frac-

tures, prolonged immobility, and mechanical ventilatory sup-

port. This means of prophylaxis has not been studied in direct

comparison with heparin or mechanical devices. Other patient

populations that may benefit from prophylactic filter place-

ment include patients with advanced malignancy, orthopedic

surgical patients, and patients with limited cardiopulmonary

reserve such as those with severe COPD. The use of these fil-

ters as prophylaxis remains controversial and requires larger

studies to determine their exact role.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

The diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in the critically ill

patient with multiple preexisting diseases can be very difficult.

The incidence of pulmonary embolism complicating critical

illness is unknown, but 5–10% of deaths may be associated

with unsuspected pulmonary emboli. In a study of patients

with COPD exacerbation, 25% of those without obvious pre-

cipitating cause had pulmonary embolism. Risk was associ-

ated with malignancy, prior venous thromboembolic disease,

and decrease in Pa

CO

2

of at least 5 mm Hg. Abnormal pul-

monary gas exchange and hemodynamic compromise result-

ing from new pulmonary emboli may not be identified in

patients who already have underlying lung or heart disease.

Defects on perfusion lung scans may or may not represent

pulmonary emboli in patients with abnormal chest x-rays,

and ventilation scans cannot be performed without special

arrangements for patients receiving mechanical ventilation.

The helical or spiral CT scan requires administration of con-

trast material and a degree of patient cooperation and breath-

holding to achieve adequate imaging. Again, this may be

difficult for critically ill patients to perform. Finally, treatment

issues are complex, with some patients having relative con-

traindications to anticoagulation and others having diseases

in which adequate anticoagulation is difficult to achieve.

Patients with worsening hypoxemia or increased physio-

logic dead space, increased pulmonary artery pressure (in the

absence of other causes), unexplained tachycardia or

hypotension, or other features of unclear cardiopulmonary

insufficiency should be suspected of having pulmonary

thromboembolic disease until proven otherwise. The use of

end-tidal CO

2

monitors in the ICU may be a noninvasive

means for detecting an acute change in dead space ventila-

tion that may be an early clue for pulmonary embolism.

Ventilation-perfusion scans in patients with COPD gen-

erally are considered to be of limited value because airway

obstruction causes falsely positive perfusion defects. A study

of such patients suspected of having a pulmonary embolism

found that high-probability scans were rare but had a high

predictive value for pulmonary embolism; similarly, a nor-

mal perfusion scan was highly predictive of a normal pul-

monary angiogram. However, 90% of the group had

intermediate-probability (60%) or low-probability (30%)

scans, of which only 17% had pulmonary embolism con-

firmed by angiography. The authors of the study concluded

that ventilation-perfusion lung scans were helpful only if

they were high-probability or normal. In all others, they con-

cluded, sufficient clinical suspicion should lead to pul-

monary angiography.

Ansell J et al: The pharmacology and management of the vitamin

K antagonists. Chest 2004;126:204–33S. [PMID: 15383473]

Augustinos P, Ouriel K: Invasive approaches to treatment of

venous thromboembolism. Circulation 2004;110:I27–34. [PMID:

15339878]

Buller HR et al: Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboem-

bolic disease. Chest 2004;126:401–28S. [PMID: 15383479]

Carlbom DJ, Davidson BL: Pulmonary embolism in the critically

ill. Chest 2007;132:313–24. [PMID: 17625093]

Chunilal SD et al: Does this patient have pulmonary embolism?

JAMA 2003;290:2849–58. [PMID: 14657070]

CHAPTER 24

562

Dong B et al: Thrombolytic therapy for pulmonary embolism.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2:CD004437. [PMID: 16625603]

Fedullo PF, Tapson VF: The evaluation of suspected pulmonary

embolism. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1247–56. [PMID: 14507950]

Geerts WH et al: Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest

2004;126:338–400S. [PMID: 15383478]

Hirsh J et al: Heparin and low-molecular weight-heparin. Chest

2004;126:188–203S. [PMID: 15383472]

Hogg K et al: Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with CT pul-

monary angiography: A systematic review. Emerg Med J

2006;23:172–8. [PMID: 16498151]

Hull RD et al: Low-molecular-weight heparin vs heparin in the

treatment of patients with pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern

Med 2000;160:229–36. [PMID: 10647762]

Kreit JW: The impact of right ventricular dysfunction on the prog-

nosis and therapy of normotensive patients with pulmonary

embolism. Chest 2004;125:1539–45. [PMID: 15078772]

Kruip MJHA et al: Diagnostic strategies for excluding pulmonary

embolism in clinic outcome studies: A systematic review. Ann

Intern Med 2003;138:941–51. [PMID: 12809450]

Kucher N et al: Massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation

2006;113:577–82. [PMID: 16432055]

Kucher N et al: Prognostic role of echocardiography among

patients with acute pulmonary embolism and a systolic arterial

pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher. Arch Intern Med

2005;165:1777–81. [PMID: 16087827]

Kucher N, Goldhaber SZ: Risk stratification of acute pulmonary

embolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 2006;32:838–47. [PMID:

17171598]

Kutinsky I et al: Normal D-dimer levels in patients with pul-

monary embolism. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1569–72. [PMID:

10421279]

Le Gal G et al: Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emer-

gency department: The revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med

2006;144:165–71. [PMID: 16461960]

Levine MN et al: Hemorrhagic complications of anticoagulant

treatment: The Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic

and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest 2004;126:287–310S. [PMID:

15383476]

Low-molecular-weight heparin in the treatment of patients with

venous thromboembolism. The Columbus Investigators. N

Engl J Med 1997;337:657–62. [PMID: 9280815]

Moores LK et al: Meta-analysis: Outcomes in patients with sus-

pected pulmonary embolism managed with computed tomo-

graphic pulmonary angiography. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:

866–74. [PMID: 15583229]

Nijkeuter M et al: The natural course of hemodynamically stable

pulmonary embolism: Clinical outcome and risk factors in a

large prospective cohort study. Chest 2007;131:517–23. [PMID:

17296656]

PREPIC Study Group: Eight-year follow-up of patients with per-

manent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary

embolism: The PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d’Embolie

Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study.

Circulation 2005;112:416–22. [PMID: 16009794]

Rocha AT et al: Venous thromboembolism in intensive care

patients. Clin Chest Med 2003;24:103–22. [PMID: 12685059]

Roongsritong C et al: Common causes of troponin elevations in

the absence of acute myocardial infarction: Incidence and clin-

ical significance. Chest 2004;125:1877–84. [PMID: 15136402]

Snow V et al: Management of venous thromboembolism: A clini-

cal practice guideline from the American College of Physicians

and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern

Med 2007;146:204–10. [PMID: 17261857]

Stein PD et al: Multidetector computed tomography for acute pul-

monary embolism. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2317–27. [PMID:

16738268]

Streiff MB: Vena caval filters: A review for intensive care specialists.

J Intensive Care Med 2003;18:105–7. [PMID: 15189653]

Tillie-Leblond I et al: Pulmonary embolism in patients with unex-

plained exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:

Prevalence and risk factors. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:390–6.

[PMID: 16549851]

Value of the ventilation-perfusion scan in acute pulmonary

embolism: Results of the prospective investigation of pul-

monary embolism diagnosis (PIOPED). The PIOPED

Investigators. JAMA 1990;263:2753–59. [PMID: 2332918]

van Belle A et al: Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary

embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-

dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA 2006;295:

172–9. [PMID: 16403929]

Weitz JI, Linkins LA: Beyond heparin and warfarin: the new gener-

ation of anticoagulants. Exp Opin Investig Drugs 2007;

16:271–82. [PMID: 17302522]

Wood KE: Major pulmonary embolism: Review of a pathophysio-

logic approach to the golden hour of hemodynamically signifi-

cant pulmonary embolism. Chest 2002;121:877–905. [PMID:

11888976]

Anaphylaxis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Follows reexposure to foreign antigens such as food,

drug, nonhuman protein, or other substances.

Respiratory tract: rhinitis, edema, laryngeal edema,

asthma.

Hypotension, lightheadedness, collapse.

Generalized erythema, pruritus, and urticarial skin

lesions with or without angioedema.

General Considerations

Anaphylaxis is a severe allergic reaction that occurs after reex-

posure to a foreign substance such as food, a drug, serum, ven-

oms, or nonhuman proteins but also occurs occasionally after

exercise. Approximately 72 hours after initial exposure to a

foreign antigen, IgE antibody synthesis begins. Reexposure to

the antigen promotes cross-linking of mast cell and basophil-

bound IgE molecules and causes the subsequent release of

stored mediators of anaphylaxis such as histamine and other

substances. These factors cause increases in capillary perme-

ability, mucosal edema, and smooth muscle contraction; acti-

vate the classic complement pathway and components of the

clotting cascade; and cause the release of other mediators.

PULMONARY DISEASE

563

Anaphylactoid (ie, anaphylaxis-like) reactions are clini-

cally similar to anaphylaxis but are not mediated by

antigen-antibody interactions. Many of the same mediators

are involved, so treatment is identical to that for anaphy-

laxis. Mechanisms include (1) activation of the comple-

ment cascade by immune complexes or other substances

that cause release of anaphylatoxins (eg, C3a and C5a),

resulting in mediator release from mast cells and

basophils, and (2) direct activation by certain agents of

mast cells and basophils resulting in mediator release (eg,

effect of hyperosmolar solutions such as mannitol and

radiocontrast media).

Patients with anaphylaxis may be admitted to the ICU

because of severe respiratory or cardiovascular compromise,

or they may develop anaphylaxis in the ICU from exposure

to blood products or drugs.

Clinical Features

The onset of a systemic anaphylactic reaction, which may

develop over minutes to 1–2 hours, depends on the sensitiv-

ity of the person as well as the route, rate, and quantity of the

precipitating agent. The clinical signs and symptoms can dif-

fer greatly depending on the severity of the anaphylactic

reaction, and clinical findings may be present in various

combinations. Severe systemic reactions are characterized by

respiratory failure and cardiovascular collapse. Recurrence of

symptoms can occur 2–24 hours after onset despite initial

stabilization and treatment.

A. History—A history of recent use of medication, ingestion

of new or unusual foods (notably peanuts and other nuts and

shellfish), and exposure to toxic products such as venoms or

insect bites should be sought, but treatment should be initi-

ated immediately if necessary. An increasingly recognized

cause of allergy and anaphylaxis is exposure to latex rubber.

About half of patients will have a history of atopy, and only

about 70% of patients who develop anaphylaxis outside

the hospital will have an identifiable precipitating cause. In

the ICU, intravenous contrast agents, antibiotics, NSAIDs,

aspirin, and other drugs are the most likely causes.

B. Symptoms and Signs—Anaphylaxis is often associated

with severe anxiety and apprehension. Patients may experi-

ence any combination of the following symptoms: itching of

skin and mucosal surfaces, swelling of the lips and tongue,

hoarseness, coughing, shortness of breath, wheezing, vomit-

ing, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and palpitations.

Physical findings in severe systemic reactions include

hypotension, upper airway obstruction resulting in stridor,

and bronchospasm with impaired gas exchange, hypercap-

nia, and wheezing. Loss of consciousness may result from

poor cerebral perfusion. Urticaria may be present, and there

may be evidence of angioedema.

Allergens injected systemically—for example, insect

stings, intravenous drugs, blood products, and allergy desen-

sitization treatments—often cause a predominantly

cardiovascular reaction with hypotension. Food and inhaled

allergens may cause more facial and respiratory edema, asso-

ciated with respiratory problems.

Differential Diagnosis

Anaphylaxis may be confused with syncopal episodes associ-

ated with metabolic or vascular disturbances, acute respira-

tory failure secondary to epiglottitis, status asthmaticus,

obstruction owing to foreign-body aspiration, and pulmonary

embolism. Similar disorders with cutaneous and respiratory

manifestations—for example, mastocytosis, carcinoid syn-

drome, hereditary angioedema, and other specific adverse

pharmacologic (allergic and nonallergic) reactions to

drugs—should be considered if appropriate.

Treatment

Treatment is based on early recognition of features of ana-

phylaxis combined with a history of exposure to an inciting

agent. The suspected agent should be discontinued if possi-

ble (eg, a drug, blood products, or contact with latex rubber),

the extent and severity of the reaction should be assessed,

and treatment should be initiated as soon as anaphylaxis is

suspected.

A. General Measures—The patient should be positioned

supine or head down with the feet elevated. The airway must

be maintained by proper positioning. If necessary, endotra-

cheal intubation, tracheostomy, or cricothyroidotomy

should be performed. Because of the need for intravenous

fluid infusion and medications, a large-bore intravenous

catheter should be inserted.

B. Initial Treatment—Epinephrine should be given first in

a dosage of 0.3–0.5 mL of 1:1000 dilution (0.3–0.5 mg)

intramuscularly deep into the thigh every 10–20 minutes as

needed. The subcutaneous route is no longer recom-

mended. In severe anaphylaxis with suspicion of poor per-

fusion, slow intravenous injection (5 mL of 1:10,000

dilution) should be considered. Other initial treatment

includes oxygen, inhaled β-adrenergic agonists for bron-

chospasm, and airway management.

C. Other Medications—Medications are directed toward

blocking further mediator action on target organs, preventing

further release of mediators, reversing the physiologic effects

of the mediators, and supporting vital functions.

Antihistamines (histamine H1-antagonists) such as

diphenhydramine hydrochloride, 25–50 mg intra-

venously every 6 hours, are useful. Some studies show

additional benefit of histamine H2-receptor antagonists, so

cimetidine or ranitidine may be given as well. Excessive

antihistamine dosages may cause impaired CNS function,

anticholinergic symptoms (eg, dry mouth or urinary reten-

tion), and drowsiness, especially in elderly patients.

Hydrocortisone, 100 mg intravenously every 8 hours for

CHAPTER 24

564

several doses, is recommended, especially if there is bron-

chospasm or airway compromise. Patients who are receiving

β-blockers may have a poor response to treatment directed at

hypotension. These patients may have some response to

glucagon, which has both inotropic and chronotropic effects

on the heart.

D. Intravenous Fluids—Adults should receive 0.9% NaCl

solution, 0.5–1 L intravenously over 30 minutes, if hypoten-

sive. Additional fluid therapy depends on blood pressure,

heart rate, urine output, and clinical response.

E. Prevention of Anaphylaxis—The patient should be

instructed to avoid the offending agent in future, if possible.

For patients who have a likelihood of reexposure to an

identified antigen, a kit containing epinephrine for self-

administration should be considered.

Angioedema

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Subcutaneous swelling of skin or mucous membranes,

possibly with laryngeal or lower airway compromise.

May present with urticaria.

Acute angioedema: may have history of ACE inhibitor,

aspirin, or NSAID therapy or a history of allergies.

History of recurrent transient episodes of swelling may

be present in allergic or hereditary forms.

General Considerations

Angioedema is produced by mechanisms similar to those

that cause anaphylaxis and anaphylactoid reactions. In addi-

tion, these mechanisms can be triggered by various physical

forces, exercise, and other medical conditions such as

endocrine disorders, infections, malignancies, allergic phe-

nomena, and collagen vascular diseases. Severe angioedema

involving the upper or lower airways is a medical emergency

similar to anaphylaxis.

Acute angioedema, which may occur once or on multiple

occasions, is often idiopathic or associated with allergic phe-

nomena. Among identified causes, the most common are

related to ACE inhibitor therapy, aspirin, and NSAIDs.

Hereditary angioedema is caused by an autosomal domi-

nant inherited deficiency or functional abnormality of C1

esterase inhibitor. Without this inhibitor, the complement

cascade is activated, and a kinin-like fragment and other

mediators are released that produce the angioedema.

Acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency is very rare and

seen in adults with autoimmune or lymphoproliferative

disorders. Patients have unexplained recurrent angioedema,

and the diagnosis is confirmed by low levels of C1q and low

C1 esterase inhibitor activity.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Angioedema is characterized by

the presence of nonpruritic subcutaneous swelling of the skin

and mucous membranes. Lesions of the skin are poorly

demarcated and reddish. These may occur in conjunction with

urticarial lesions. Involvement of the upper airway can result

in hoarseness, stridor, shortness of breath, and even death.

Likewise, GI involvement is associated with abdominal pain,

nausea, and diarrhea. Patients may or may not have associated

urticaria, characterized by evanescent pruritic lesions.

Because of widespread use of ACE inhibitors for hyperten-

sion, diabetic proteinuria, and congestive heart failure, these

agents are a common cause of acute angioedema. This disor-

der may present after recent initiation of ACE inhibitor ther-

apy but may occur even after prolonged use. It is said that

urticaria is unusual in ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema.

Angiotensin-receptor blockers, sometimes given to patients

instead of or in addition to an ACE inhibitor, rarely have

been associated with angioedema, but some experts have

cautioned against use of these agents in patients with ACE

inhibitor–induced angioedema. Hereditary or acquired

angioedema has been precipitated by ACE inhibitors.

In hereditary angioedema, episodes can be precipitated

by trauma, emotional upset, infections, and exposure to sud-

den temperature changes. The disorder usually is apparent in

childhood, and attacks tend to be recurrent and usually are of

2–4 days duration. The physical findings are similar to those

described earlier. Similar features are present in acquired

forms of angioedema.

B. Laboratory Findings—In patients with angioedema or

urticaria, investigation should include a complete blood

count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and urinalysis. Other

laboratory tests should be ordered depending on the under-

lying medical condition. In patients with abdominal symp-

toms, edema of the bowel wall may be seen on CT scan.

When hereditary angioedema is suspected, C4, C3, CH50

or total complement, and C1 esterase inhibitor (by immuno-

chemical and functional assay) should be measured. Levels of

C4 and C2 are always low, and CH50 is usually diminished or

absent during an attack. C1 esterase will be reduced but may

be normal in persons with a functional abnormality.

Acquired angioedema (acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency) is

due to increased catabolism of C1 esterase inhibitor and C1q.

Laboratory findings in allergic angioedema and that induced

by ACE inhibitors and NSAIDs are rarely specific or helpful.

Treatment

Patients may require long-term treatment and should avoid

precipitating conditions and situations. In some patients, the

underlying cause may not be identifiable.

PULMONARY DISEASE

565

A. General Measures—Acute angioedema is treated ini-

tially much the same way as anaphylaxis. The underlying

cause should be treated or removed, especially if ACE

inhibitors have been implicated. Hypotension and shock

should be treated with intravenous fluids. The airway

should be protected, and endotracheal intubation may

become necessary. If there is severe upper airway obstruction,

tracheostomy should be considered.

B. Specific Treatment

1. Epinephrine—Epinephrine is indicated for patients with

severe acute urticaria or angioedema with airway involve-

ment. It can be given subcutaneously or intravenously. One

recommendation is to give 0.3–0.5 mL of 1:1000 solution

subcutaneously and repeat every 10–20 minutes as necessary.

Epinephrine may be lifesaving in angioedema, but it should

be noted that many patients with ACE inhibitor–induced

angioedema are elderly or have heart disease or hyperten-

sion. Epinephrine may cause excessive tachycardia, may

increase myocardial oxygen demand, may provoke myocar-

dial ischemia, and may raise blood pressure excessively.

2. Antihistamines—Antihistamines usually are effective

against urticaria and can be helpful for some forms of

angioedema. H1-blockers such as diphenhydramine, 50 mg

orally or intravenously every 6 hours, are helpful for an acute

episode of urticaria. Patients may have dry mouth, drowsi-

ness, and excessive sedation with these agents. In patients

with angioedema, in addition to H1-blockers, an H2-blocker

such as ranitidine, 50 mg intravenously two or three times

daily or 150 mg orally twice daily, or cimetidine, 300 mg

orally or intravenously every 6 hours, may be helpful.

3. Corticosteroids—Corticosteroids usually are not nec-

essary for acute urticaria alone but can be very helpful in

refractory acute urticaria or chronic urticaria. A recom-

mended initial dosage is prednisone, 2 mg/kg per day

orally, or methylprednisolone, 60 mg intravenously every

6 hours.

C. Hereditary Angioedema—Clinical trials of recombinant

C1 inhibitor concentrate for acute hereditary angioedema

are under way. C1 inhibitor concentrates from pooled

plasma are available in Europe but not in the United States.

Fresh frozen plasma may be given (2 units) as treatment to

prevent angioedema or in preparation for surgery. Long-

term preventive treatment of angioedema can be tried using

androgen derivatives such as danazol, 200 mg orally three

times daily, or stanozolol, 2–4 mg/day.

Bochner BS, Lichtenstein LM: Anaphylaxis. N Engl J Med

1991;324:1785–90. [PMID: 1789822]

Bork K, Barnstedt SE: Treatment of 193 episodes of laryngeal

edema with C1 inhibitor concentrate in patient with hereditary

angioedema. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:714–8. [PMID:

11231704]

Kleiner GI et al: Unmasking of acquired autoimmune C1-inhibitor

deficiency by an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Ann

Allergy Asthma Immunol 2001;86:461–4. [PMID: 11345293]

Lieberman P: Use of epinephrine in the treatment of anaphylaxis.

Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;3:313–8. [PMID:

12865777]

Lin RY et al: Improved outcomes in patients with acute allergic

syndromes who are treated with combined H

1

and H

2

antago-

nists. Ann Emerg Med 2000;36:462–8. [PMID: 11054200]

566

00

Several endocrine problems may require management in the

ICU, including severe thyroid disease, acute adrenal insuffi-

ciency, and diabetic ketoacidosis. While these problems usu-

ally are encountered in patients in whom a diagnosis of

endocrine dysfunction has already been made, they are occa-

sionally the presenting manifestation in an undiagnosed

patient. If these endocrine disorders are not identified, spe-

cific treatment such as endocrine replacement therapy may be

delayed, and significant complications or death may ensue.

In this chapter, severe thyrotoxicosis (eg, thyroid storm or

decompensated hyperthyroidism), severe hypothyroidism

(eg, myxedema coma), and acute and chronic adrenal insuffi-

ciency are discussed. Diabetic ketoacidosis and other manifes-

tations of severe diabetes mellitus are covered in Chapter 26.

In this chapter we also discuss the problem of assessing thy-

roid function in severe nonthyroidal illness (ie, sick euthyroid

syndrome).

Thyroid Storm

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Long-standing hyperthyroidism, uncontrolled or poorly

controlled.

Breakdown of the body’s thermoregulatory mechanisms,

resulting in hyperpyrexia.

Altered mental status.

Precipitating illnesses or events such as thyroid sur-

gery, infection, trauma, acute abdominal problems, or

anesthesia.

Signs and symptoms of severe hyperthyroidism—usually

marked wasting.

General Considerations

Thyroid storm—or thyrotoxic crisis—results from the even-

tual failure of the body’s compensatory mechanisms in

severe hyperthyroidism. Clinically, thyroid storm has been

defined as “a life-threatening augmentation of the manifesta-

tions of hyperthyroidism.” There are no pathognomonic lab-

oratory markers of thyroid storm. However, because of its

high mortality rate, one should be vigilant for its diagnosis

and provide aggressive and prompt management. This is

especially true because the features of thyroid storm are com-

mon findings in other critically ill patients.

A. Incidence—The incidence of thyroid storm has decreased

markedly since the advent of antithyroid drugs. Some studies

suggest that the incidence is 2–8% of all patients admitted to

the hospital for management of hyperthyroidism. However, a

recent evaluation at a major teaching hospital revealed that

severe complicated thyrotoxicosis is a rare syndrome,

accounting for only 0.01% of hospital admissions over a

14-year period. Thyroid storm occurs nine to ten times more

commonly in women than in men, probably a reflection of

the higher incidence of thyroid diseases in women in general.

No race- or age-related differences in incidence have been

reported. An association between thyroid storm and med-

ically underserved, socially disadvantaged populations has

been suggested. In one study, patients admitted because of

complicated thyrotoxicosis were more likely to be uninsured,

poorer, unmarried, and African-American than uncompli-

cated thyrotoxic controls. One explanation is that control of

chronic hyperthyroidism with antithyroid drugs is very effec-

tive in preventing decompensation, but poorer populations

may be less likely to receive adequate treatment.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of thyrotoxic crisis is not well under-

stood. Indices of thyroid gland overactivity (levels of total

and free thyroxine or triiodothyronine) are not significantly

higher than in usual cases of hyperthyroidism.

25

Endocrine Problems in the

Critically Ill Patient

∗

Shalender Bhasin, MD

Piya Ballani, MD

Ricky Phong Mac, MD

∗

Shalender Bhasin, MD, Laurie K. S. Tom, MD, and Phong Mac, MD,

were the authors of this chapter in the second edition.

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.