Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GASTROINTESTINAL FAILURE IN THE ICU

357

Pancreatic Insufficiency

Following pancreatic surgery, pancreatectomy, or pancreati-

tis, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency can develop. Varying

degrees of insufficiency may be present without overt symp-

toms. Following total pancreatectomy, malabsorption of

70% of dietary fat is common. However, in the face of a nor-

mal pancreatic remnant, some resections have little or no

effect on fat absorption.

Patients with pancreatic insufficiency have increased fecal

fat and decreased serum cholesterol. Steatorrhea manifests as

frequent, bulky, light-colored stools. A loss of 90% of pancre-

atic exocrine function is required before such findings

appear. If the patient retains 2–10% of normal pancreatic

function, steatorrhea is mild to moderate. If less than 2% of

normal function remains, steatorrhea is severe.

Pancreatic insufficiency affects fat absorption more than

that of proteins or carbohydrates. Malabsorption secondary

to fat loss or vitamin deficiency is rarely a problem. B vita-

mins, which are water-soluble, are absorbed through the

small intestine. Fat-soluble vitamins depend on bile salt

micelle formation for solubilization and do not require pan-

creatic enzymes for absorption. Vitamin B

12

deficiency

occurs rarely but, when present, is an indication for exoge-

nous enzyme replacement.

Diagnosis

A. Secretin or Cholecystokinin Test—The duodenum is

intubated and pancreatic juice recovered after intravenous

injection of synthetic or purified secretin or cholecystokinin.

Optimally, pancreatic fluid bicarbonate should exceed 80

meq/L, and bicarbonate production should be greater than

15 meq every 30 minutes.

B. Pancreolauryl Test—A meal containing fluorescein

dilaurate is ingested, and the subsequent urinary excretion of

fluorescein is measured. Pancreatic esterase is responsible for

the absorption and release of fluorescein. The test is both

specific and sensitive and is the best modality for testing pan-

creatic exocrine function.

C. PABA Excretion (Bentiromide Test)—The synthetic

peptide bentiromide is administered (1 g orally), and the uri-

nary excretion of aromatic amines is measured. Patients with

chronic pancreatitis excrete about 50% of the normal

amount of the amines.

D. Fecal Fat (Balance) Measurement—A diet contain-

ing 75–100 g of fat—measured and given in the same

amount each day—is ingested daily for 5 days. Excretion of

less than 7% of the ingested fat is normal. Fat excretion of

more than 25% of the total daily intake suggests significant

steatorrhea.

Treatment

The diet should provide 3000–6000 kcal daily. Patients with

steatorrhea may not have diarrhea. Dietary fat restriction is

intended primarily to control diarrhea. If a patient does have

diarrhea and is restricted to 50 g fat, the daily allotment of fat

should be increased until the diarrhea reappears.

Pancreatic enzyme replacement can be accomplished

with exogenous extracts. With these formulations,

30,000–50,000 units of lipase can be distributed over several

feedings during the day. If malabsorption does not improve

with enzymes alone, the difficulty is usually due to destruc-

tion of the administered lipase by gastric acid. To alleviate

this problem, an H2-receptor–blocking agent is given and an

enteric-coated lipase formulation provided. When lipase is

administered in this form, the gastric pH is less likely to

affect the enzyme.

Caloric supplementation may be given in the form of

powder or as an oil containing medium-chain triglycerides

(MCTs). The fatty acids are absorbed more readily in this

preparation than when long-chain triglycerides are used. The

MCT oil is associated with bloating, diarrhea, nausea and

vomiting, and very poor patient acceptance.

Lactase Deficiency

Lactase deficiency is a common problem among critically ill

patients. The symptoms are variable and can range from

minor abdominal bloating to distention, flatulence, and

cramping pain. Some patients, however, have severe diarrhea

in response to only a small amount of lactose. Although a

lactose tolerance test is available, clinical suspicion and rela-

tion of the diarrhea to the time of refeeding usually suggest

the diagnosis. Illnesses such as gastroenteritis may injure the

microvilli and lead to a temporary lactase deficiency. Several

congenital defects of disaccharidase have been described.

Most patients will give a history of dietary problems with

milk products, but the difficulties occasionally surface at

times of physiologic stress. They include sucrose-isomaltose

and glucose-galactose intolerance. Disaccharide deficiency

secondary to short bowel syndrome, celiac disease, giardiasis,

ulcerative colitis, cystic fibrosis, and postgastrectomy prob-

lems may be noted. In all cases, removal of lactose from the

diet and use of a non-lactose-based enteral nutritional sup-

plement usually solve the problem.

Choosing and using a pancreatic enzyme supplement. Drug Ther

Bull 1992;30:37–40. [PMID: 1591984]

Gillanders L et al: Dietary management of the patient with massive

enterectomy. N Z Med J 1990;103:322–3. [PMID: 2115150]

Hammer HF et al: Carbohydrate malabsorption: Its measurement

and its contribution to diarrhea. J Clin Invest 1990;86:1936–44.

[PMID: 2254453]

Nightingale JM et al: Short bowel syndrome. Digestion 1990;45:77–83.

Romano TJ, Dobbins JW: Evaluation of the patient with suspected

malabsorption. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1989;18:467–83.

[PMID: 2680965]

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is defined as an increase in the fluidity, frequency,

or quantity (>200 g/day) of bowel movements. Several

CHAPTER 14

358

factors to be considered in the evaluation of diarrhea may

influence the frequency or even the fluidity of bowel move-

ments. Malabsorption or excessive secretion of water usually

results in passage of stools that contain excess water and are

therefore considered as diarrhea. The best index is daily stool

weight. Therefore, one may have small-volume diarrhea,

large-volume diarrhea, and other variants that depend on the

content of blood, mucus, or exudate. The various types of

diarrhea are listed in Table 14–2. Common causes of diarrhea

among patients in an ICU include psychogenic disorders,

drugs (especially antacids, antibiotics, and metoclopramide),

intestinal infections, cholestatic syndromes (eg, hepatitis, bile

duct obstruction, and steatorrhea), malabsorption (eg, short

bowel syndrome and afferent loop syndrome), diabetic neu-

ropathy, hyperthyroidism, and immunodeficiency.

Diagnosis

In general, diarrheal episodes are self-limiting, and diagnos-

tic testing is not necessary. However, in patients with unex-

plained severe or chronic diarrhea, etiologic evaluation may

become necessary. Review of the patient’s chart, evaluation

of drugs being used, and physical examination are often all

that are needed to establish the cause. Examination of stool

for polymorphonuclear cells and parasites and culture for

bacterial pathogens may be required. A sample for culture is

best obtained with the sigmoidoscope. Rectal biopsy may be

helpful and even necessary, especially when Entamoeba his-

tolytica infection is suspected. Assays of stool for Clostridium

difficile toxin are highly accurate and establish the diagnosis

of pseudomembranous enterocolitis.

Treatment

Before specific therapy for diarrhea is begun, it is important

to make certain that fluid losses have been replaced and elec-

trolyte imbalances corrected. Malnutrition should be man-

aged with parenteral nutrition.

Antidiarrheal agents should be used with great caution

and attention to the patient’s critical care history. The

antidiarrheal agent used most commonly is bismuth subsal-

icylate. This can be given in liquid or tablet form. The usual

dose is 30 mL up to eight times a day. Opioid analogs are also

popular; the most frequently prescribed form is diphenoxy-

late with atropine, one tablet three or four times daily as

needed. This drug is contraindicated in patients with jaun-

dice or pseudomembranous or endotoxin colitis and must be

used with caution in patients with advanced liver disease or

those who are addiction-prone. Concurrent use of this med-

ication with monoamine oxidase inhibitors may precipitate a

hypertensive crisis. A secondary drug is loperamide, 4 mg

initially and then 2 mg for each loose stool to a maximum

dose of 16 mg/day. Loperamide is effective in both acute and

chronic diarrhea. Opioids such as paregoric and codeine

phosphate were popular in the past but have little role in crit-

ically ill patients.

Clonidine, when administered as a 1-mg patch, is useful

in patients who have diabetes or cryptosporidiosis.

Octreotide acetate is useful when diarrhea is due to carcinoid

tumors, VIPoma, or AIDS. It is usually started at a dose of

50 μg subcutaneously once or twice daily. For carcinoid

and VIPomas, the required dose may be higher but averages

300 μg/day in two to four divided doses.

Grube BJ, Heimbach DM, Marvin JA: Clostridium difficile diarrhea

in critically ill burned patients. Arch Surg 1987;122:655–61.

[PMID: 3579579]

Pesola GR et al: Hypertonic nasogastric tube feedings: Do they

cause diarrhea? Crit Care Med 1990;18:1378–82. [PMID:

2123143]

Tibibian N: Diarrhea in critically ill patients. Am Fam Phys

1989;40:135–40.

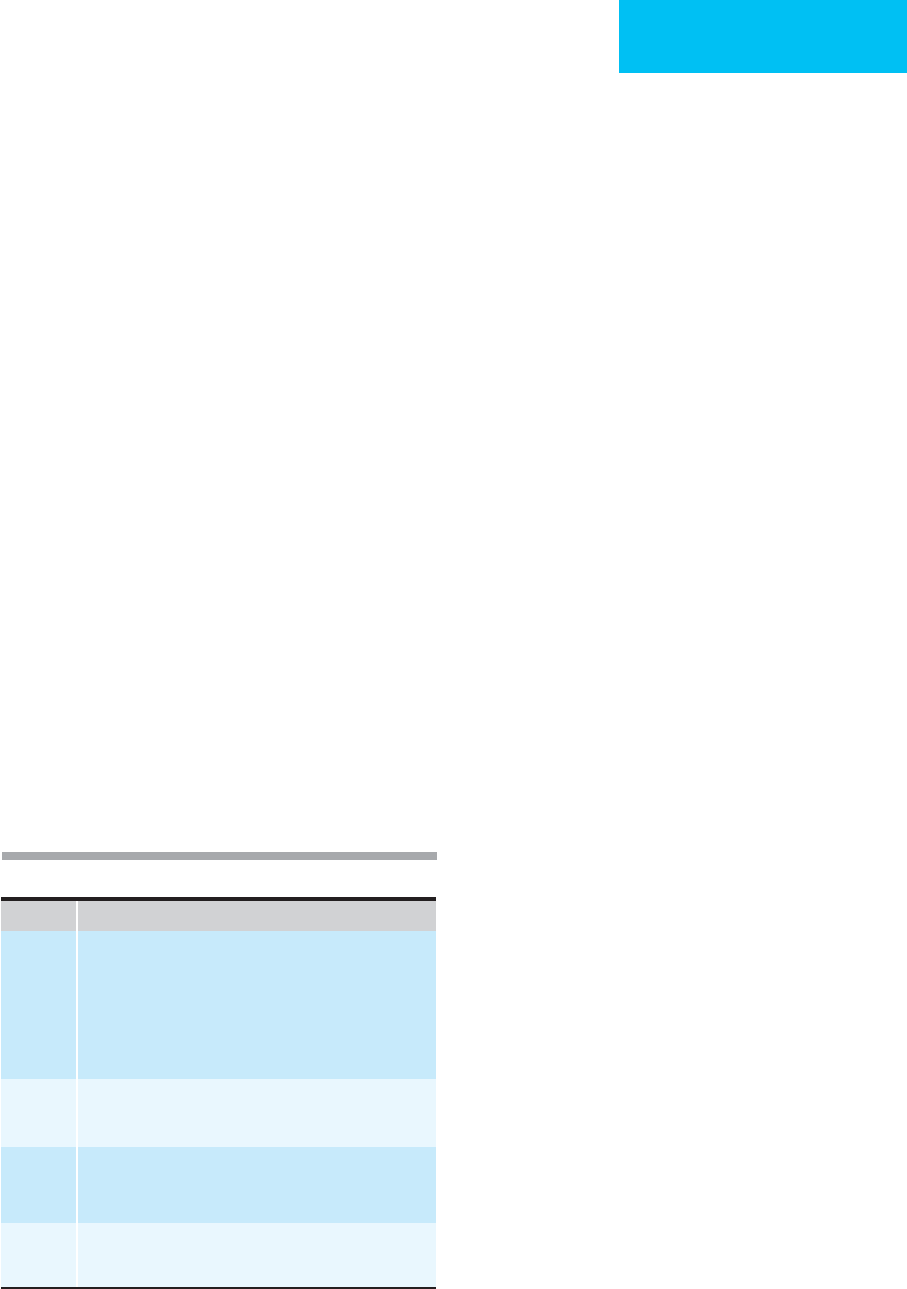

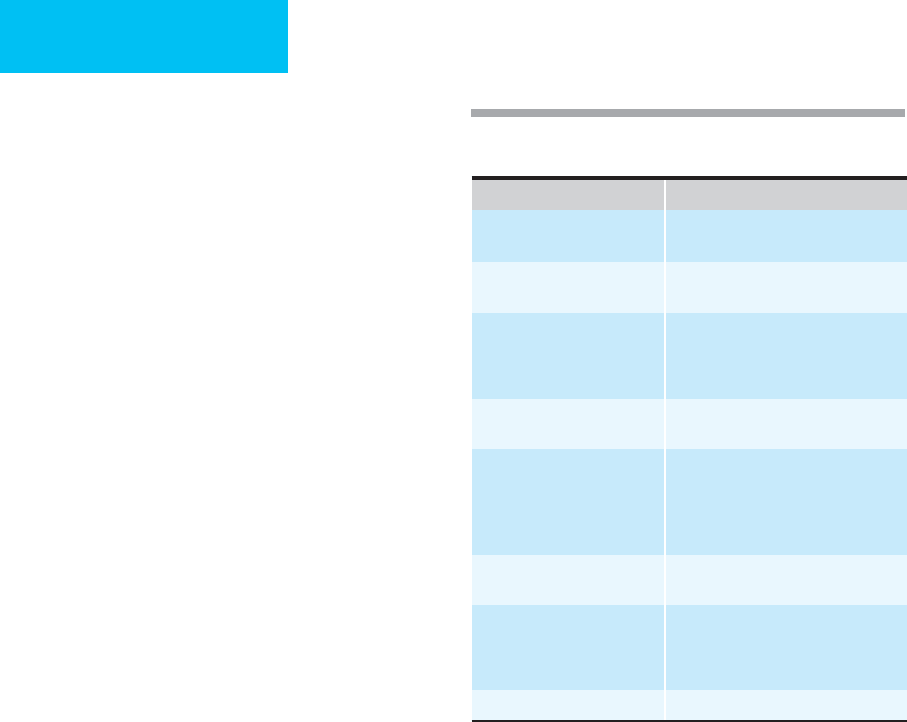

Table 14–2. Classification of diarrhea.

I. Diarrhea secondary to excessive fecal water:

A. Secretory diarrhea: Produced by excessive secretion by the

mucosal cells of the intestine. Causes: cholera, toxigenic

E. coli

infections, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, and VIPoma.

B. Osmotic diarrhea: Produced by an excess of water-soluble

molecules in the lumen of the bowel, which cause osmotic reten-

tion of intraluminal water. Causes: Abuse or surreptitious use of

laxatives, administration of magnesium hydroxide, or undigested

disaccharides.

C. Exudative disease: Produced by intestinal loss of serum proteins,

blood, mucus, or pus due to abnormal mucosal permeability.

D. Accelerated transport: Impaired contact between intestinal chyme

absorbing surface, which results in rapid transport. Common in

short bowel syndromes.

E. Motility disturbances: Causes: Amyloidosis, scleroderma, diabetes

mellitus, and bacterial overgrowth.

II. Diarrhea not secondary to excessive fecal water:

A. Small, frequent, and painful evacuations caused by partial

obstruction of the left colon or rectum.

359

15

Infections in the

Critically Ill

Laurie Anne Chu, MD

Mallory D. Witt, MD

The management of infected critically ill patients is a chal-

lenge for ICU physicians and staff. Patients admitted with

symptoms prior to hospitalization are considered to have

community-acquired infections, and those who develop

infection more than 48 hours following admission are con-

sidered to have hospital-acquired, or nosocomial, infections.

Seriously ill patients presenting with fever must be quickly

evaluated for possible infection because most are treatable.

However, drug fever, hypersensitivity reaction, collagen-

vascular disease, neoplastic disease, pulmonary embolism,

trauma, burns, pancreatitis, hypothalamic dysfunction, and

other noninfectious causes of fever must be considered in the

differential diagnosis.

In contrast, some patients may appear to be stable but

nonetheless have serious infections. Elderly patients, uremic

patients, and patients with end-stage liver disease or those

receiving corticosteroids often will fail to mount a signifi-

cant febrile response even to serious infection. In addition,

some infections are notorious for presenting with minimal

symptoms—these include infective endocarditis, sponta-

neous bacterial peritonitis, intraabdominal abscess, endoph-

thalmitis, and meningitis. In the absence of other symptoms

and signs, fever in the asplenic patient, the neutropenic or

immunosuppressed patient, the intravenous drug user or

alcoholic, and the elderly patient requires a rapid and thor-

ough diagnostic evaluation.

The infectious syndromes that may require direct admis-

sion and immediate therapy in the ICU—sepsis, community-

acquired pneumonia, urosepsis, infective endocarditis,

intraabdominal infections, and necrotizing soft tissue

infections—will be described in the following sections.

Special hosts such as patients with diabetes, asplenia or neu-

tropenia patients, and corticosteroid-treated individuals will

be discussed because they often have unique presentations

and complications. Care of the HIV-infected patient is discussed

in Chapter 27.

This chapter also will focus on other nosocomially

acquired infections that are of great concern to the critical

care physician either because of a high mortality rate, diag-

nostic challenge, frequency of occurrence, contagiousness, or

acquisition of antimicrobial resistance. Two unique disease

entities—botulism and tetanus—also will be discussed in

this chapter.

Sepsis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Wide spectrum of clinical findings ranging from fever,

hypothermia, tachycardia, and tachypnea to profound

shock and multiple-organ-system failure.

Severe or complicated sepsis: lactic acidosis, acute res-

piratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute renal failure,

disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), shock,

CNS dysfunction, or hepatobiliary disease.

May present with altered mental status, unexplained

hyperventilation, or tachycardia alone.

Often an identifiable site of infection.

Predisposing risk factors for infection: organ system fail-

ure, bed rest, invasive procedures, any antibiotic use,

immunocompromised state.

General Considerations

To avoid ambiguity in interpreting the results of clinical tri-

als and to facilitate communication among clinicians, it has

been recommended that specific terminology be used when

referring to sepsis and sepsis syndromes. The systemic inflam-

matory response syndrome (SIRS) is the body’s response to

various insults, both infectious and noninfectious. Patients

with two or more of the following criteria are considered to

have SIRS: (1) temperature greater than 38°C or less than

36°C, (2) heart rate greater than 90 beats/min, (3) respiratory

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 15

360

rate greater than 20 breaths/min, and (4) white blood cell

count greater than 12,000 cells/μL, less than 4000 cells/μL, or

more than 10% immature (band) forms. Sepsis is defined as

the SIRS in response to infection. Severe sepsis is defined as

sepsis associated with organ dysfunction. Septic shock is

defined by the additional finding of refractory hypotension

(ie, hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation).

Multiple-organ-system dysfunction syndrome is defined as the

presence of altered organ function such that homeostasis

cannot be maintained without intervention. The vague terms

sepsis syndrome and septicemia no longer should be used.

Sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock can be considered

points on a continuum describing increasing severity of an

individual patient’s systemic response to infection. A prospec-

tive observational study demonstrated that among hospital-

ized patients meeting the criteria for SIRS, 26% subsequently

developed sepsis, 18% developed severe sepsis, and 4% devel-

oped septic shock. The interval from SIRS to severe sepsis and

septic shock was inversely correlated with the number of SIRS

criteria met. The mortality rates of sepsis, severe sepsis, and

septic shock were 16%, 20%, and 46%, respectively.

Sepsis and septic shock are encountered commonly in

ICUs. Septic shock with multiple-organ-system failure is the

most common cause of death in ICUs. There are currently

over 750,000 new episodes of sepsis each year in the United

States compared with 1979, when approximately 200,000

cases were reported. The greatest rise occurred in persons

over 65 years of age, but increases have been noted in all age

groups. This rising incidence is the result of more aggressive

support of seriously ill patients, the care of more immuno-

compromised patients, use of more mechanical and invasive

devices (eg, bladder catheters, endotracheal tubes, and

intravascular catheters) in ICUs, increased longevity of

patients with susceptibility to infection, and increasing preva-

lence of resistant organisms. Given the expanding use of inva-

sive maneuvers in critically ill patients, it is likely that the

number of cases will continue to rise. The mortality rate from

sepsis ranges from 20–50% in published studies, with over

210,000 patients dying each year. The immediate cause of

death is usually septic shock or multiple-organ-system failure.

Pathophysiology

The complex pathophysiology of sepsis is not completely

understood. Sepsis begins with colonization and proliferation

of microorganisms at a tissue site. Various host characteristics

and organism virulence factors determine both invasiveness

and subsequent intensity of the local inflammatory response.

Replicating microorganisms release numerous exogenous

enzymes and toxins that, in turn, trigger the release of

endogenous mediators, resulting in both local and systemic

inflammatory responses. The exogenous substances differ by

type of microorganism. In the case of gram-negative bacilli,

endotoxin (lipid A) contained in the outer cell membrane is

the chief toxic substance that initiates the cascade of events

clinically recognized as sepsis or septic shock. Endotoxin

activates the complement cascade and Hageman factor,

leading to initiation of both coagulation and fibrinolysis.

Prekallikrein is converted to kallikrein, resulting in the pro-

duction of bradykinin, a mediator of hypotension.

Endotoxin, after binding with and activating macrophages,

also initiates the production of numerous endogenous

cytokines. The biologic effects of these mediators are ampli-

fied, causing host injury by way of endothelial inflammation,

abnormalities in vascular tone, altered regulation of coagula-

tion, and myocardial depression. Many of these endogenous

mediators have been identified. Tumor necrosis factor, platelet-

activating factor, interleukins, interferon, prostaglandins,

thromboxane, leukotrienes, complement components C3a

and C5a, and others factors have been shown to mediate and

trigger the pathophysiologic events.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), probably the key endoge-

nous mediator, acts on a variety of cells, stimulating produc-

tion of other cytokines involved with sepsis and septic shock.

Plasma TNF concentrations are elevated in both gram-negative

and gram-positive sepsis. While endotoxin triggers TNF pro-

duction in gram-negative sepsis, the stimulus for release of

TNF in gram-positive sepsis is unknown. However, recent

studies have shown that mediators other than endotoxin can

induce TNF production, including IFN-α, prostaglandin E

2

,

immune complexes, and colony-stimulating factors.

Pathophysiologic factors in gram-positive bacterial sepsis

are not clearly defined. In the case of Staphylococcus aureus

strains that cause toxic shock syndrome, toxic shock syn-

drome toxin 1 (TSST-1) is the principal exogenous mediator.

Some virulent strains of group A β-hemolytic streptococci

produce similar toxins.

Microbiologic Etiology

Virtually any microorganism can cause sepsis or septic

shock, including bacteria, viruses, protozoa, fungi, spiro-

chetes, and rickettsiae. Bacteria remain the most common

etiologic agent responsible for sepsis.

Gram-negative sepsis cannot be distinguished from gram-

positive sepsis on the basis of clinical characteristics alone.

However, certain epidemiologic, host, and clinical factors

increase the likelihood of particular organisms. For example,

Escherichia coli is the most frequently demonstrated etiologic

agent of sepsis largely because the urinary tract is the most

common source of infection. The incidence of infection

caused by other gram-negative bacteria, staphylococci, strep-

tococci, anaerobes, Candida, and other organisms is largely

determined by epidemiologic and host factors that may be

identified by a thorough history and physical examination.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs of Sepsis—Sepsis can present

with a spectrum of clinical features ranging from fever,

tachycardia, and tachypnea to profound shock and multiple-

organ-system (MOS) failure. The challenge to the critical

care specialist is to make the diagnosis early in the course of

the disease to increase the likelihood of a successful outcome.

INFECTIONS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL

361

Early in its course, the diagnosis of sepsis may not be obvi-

ous. Moreover, debilitated patients may not exhibit signifi-

cant symptomatology at the onset of sepsis.

Implicit in the term sepsis is a documented site of infection

along with systemic signs and symptoms of fever (or

hypothermia), tachycardia, and tachypnea (Table 15–1). In

more severe or complicated sepsis, there is also impaired organ

system function, including lactic acidosis, ARDS, acute renal

failure, DIC, CNS dysfunction, and shock. A systolic blood

pressure of less than 90 mm Hg or a decrease from baseline of

over 40 mm Hg signifies septic shock. Septic shock can be fur-

ther subclassified into responsive and refractory shock states.

Patients who do not respond to aggressive fluid resuscitation

and who require dopamine at a rate of more than 6 μg/kg per

minute (or other vasopressor agents) are considered to be in

refractory shock, which confers a very poor prognosis.

Patients with clinical features of sepsis must be evaluated

carefully, with particular attention paid to their immune sta-

tus, clinical condition, and presence of specific epidemio-

logic factors. The main purpose of the physical examination

in the septic patient is to identify the source of infection and

to note the presence of shock. In particular, a search for a

focus of infection that may require surgical drainage should

be undertaken because these patients are unlikely to respond

to antibiotics alone.

B. Laboratory Findings—Patients suspected of having

sepsis should have relevant cultures obtained to document

the infection and laboratory testing to identify metabolic or

hematologic derangements. No single laboratory test is spe-

cific for sepsis. An elevated white blood cell count is nonspe-

cific and cannot differentiate infection from inflammatory or

other pathologic states. However, an increase in immature

polymorphonuclear white blood cells (bands) strongly sug-

gests infection. Routine serum electrolytes, blood urea nitro-

gen, serum creatinine, and liver function tests may assist in

determining the site of infection as well as identifying com-

plications of sepsis such as acute renal failure or hepatobil-

iary dysfunction. Arterial blood gases, plasma lactate, and

coagulation tests may demonstrate respiratory insufficiency,

metabolic acidosis, and DIC, respectively.

Although most septic patients are intermittently bac-

teremic or fungemic, only 40% have a pathogen identified by

blood cultures. Nevertheless, blood cultures should be

obtained in every patient suspected of having sepsis. The lab-

oratory may use special procedures and blood culture equip-

ment to enhance growth and isolation of fungi, including

Candida. Two sets of blood cultures, as well as urine, respira-

tory secretions, and wound exudates, for Gram staining and

culture should be collected. If indicated by clinical findings,

cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, ascites fluid, and joint fluid

should be analyzed as well.

C. Imaging Studies—A chest radiograph may serve to iden-

tify pneumonia or ARDS; other studies such as ultrasonogra-

phy, CT scan, or MRI may be necessary to identify the site of

infection.

Differential Diagnosis

Many clinical conditions can resemble sepsis, septic shock,

and MOS dysfunction syndrome. Patients with severe burns,

multiple trauma, severe hemorrhagic or necrotizing pancre-

atitis, pulmonary emboli, acute myocardial infarction, and

various metabolic and hematologic abnormalities may have

features that mimic sepsis and its complications.

Treatment

Despite modern therapy, the mortality rate in sepsis is still

unacceptably high. However, the mortality rate can be

reduced by early diagnosis and prompt initiation of appro-

priate therapy. A delay in therapy permits the pathophysio-

logic events in sepsis to proceed, with a concomitant increase

in morbidity and mortality.

A. Supportive Care—Treatment of sepsis begins with oxy-

gen and ventilatory support as needed. The P

O

2

should be

maintained above 60–65 mm Hg with oxygen delivered by

cannula, mask, or respirator, if necessary.

The administration of intravenous fluids, either crystalloid

or colloid, expands the intravascular volume to correct the

relative deficit resulting from vasodilation owing to bacterial

products or host responses. Administration of several liters

of intravenous fluids is usually required over the first 2–6

hours. If cardiogenic pulmonary edema is a concern, pul-

monary arterial catheterization and monitoring may assist in

guiding appropriate fluid administration. Hypotension may

persist despite fluid replacement because of very low systemic

vascular resistance; in some patients, decreased myocardial

contractility associated with sepsis may contribute. The goal of

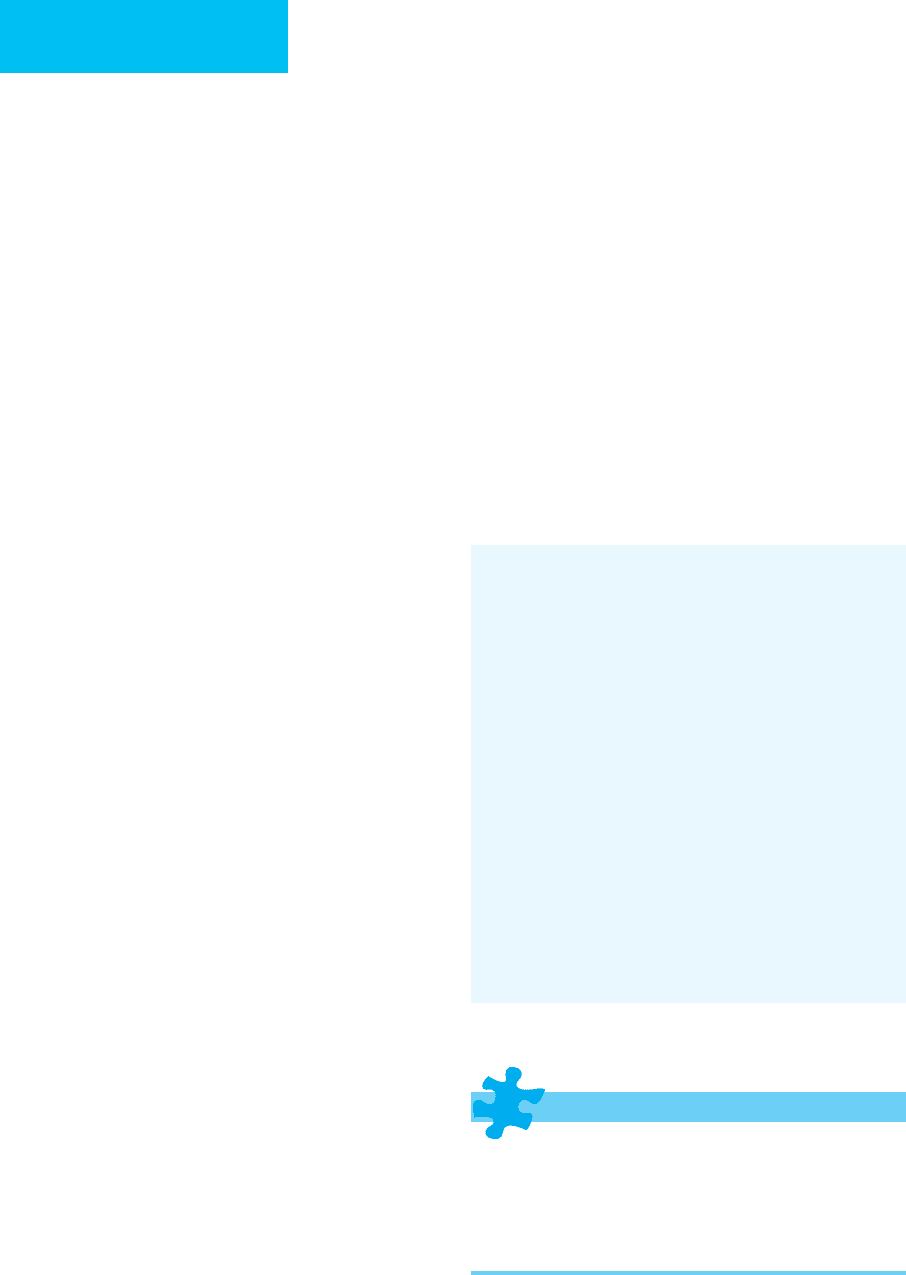

Stage Characteristics

I Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Two or

more of the following:

1. Temperature >38°C or <36°C

2. Heart rate >90 per minute

3. Respiratory rate >20 per minute

4. White blood cell count >12,000/μL or <4000/μL or

>10% bands

II Sepsis

SIRS plus a culture-documented

infection

III Severe sepsis

Sepsis plus organ dysfunction (lactic acidosis, oliguria,

hypoxemia, or acute alteration in mental status)

IV Septic shock

Severe sepsis plus hypoperfusion (despite fluid resuscitation)

Table 15–1. Definitions of stages of sepsis.

CHAPTER 15

362

initial resuscitation is to restore and maintain organ perfusion.

Signs of adequate organ perfusion include central venous pres-

sure of 8–12 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg or

greater, urine output of 0.5 mL/kg per hour or more, and cen-

tral venous or mixed venous oxygen saturation of 70% or more.

Vasopressor agents should be used to assist in attaining these

goals. Norepinephrine is generally preferred over dopamine or

other pressors. Patients not responding to norepinephrine may

require the addition of phenylphrine or vasopressin. The use of

vasopressin may allow a reduction in the dose of the other vaso-

pressors, but this is controversial. Vasopressors are not effective

when fluid replacement has been inadequate.

A coordinated approach to early treatment of sepsis is associ-

ated with reduced mortality. This “early goal-directed” therapy,

targeted on the first 6 hours of care in the emergency department

and ICU, focuses on adequate fluid replacement first (to achieve

central venous pressure of 8–12 mm Hg) and then vasopressors

as needed to maintain a mean arterial pressure of greater than

65 mm Hg. Oxygen delivery is assessed using central venous O

2

saturation, with a goal of greater than 70%. First, if the patient is

anemic, packed red blood cells are transfused to a target hemo-

globin of at least 10 g/dL. If central venous O

2

saturation remains

less than 70%, then dobutamine is given.

B. Antibiotics—The next therapeutic challenge is choosing

appropriate antibiotics. All available clinical, epidemiologic,

and laboratory data should be considered in making this

decision. Rarely is the causative microorganism known at the

time treatment for sepsis is initiated, but if the source can be

determined and/or if a Gram-stained specimen of infected

material (eg, sputum, urine, or purulent drainage) can be

examined, the long list of possible microorganisms often can

be shortened. The following sections will provide a guide to

initial antimicrobial selection depending on the potential

source of infection. Importantly, intravenous antibiotics

must be given without delay and at appropriate doses.

Adjustments for age and renal and hepatic dysfunction are

not required for the starting dose of antibiotics.

C. Surgical Drainage—Significant collections of purulent

material must be drained and necrotic tissue excised in order

to treat sepsis. Surgeons may be reluctant to operate because of

the coexistence of acute renal failure, ARDS, or other organ

system failure, but the pathophysiologic consequences of sep-

sis will tend to continue unless surgical drainage is performed.

D. Adjunctive Therapy—In the last several years, there has

been renewed interest in using corticosteroids for sepsis and

septic shock, with a large French trial showing improved sur-

vival with approximately physiologic replacement with

hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone. The benefit was seen

among patients who failed to increase plasma cortisol levels

by more than 9 μg/mL in response to adrenocorticotropic

hormone (ACTH). This was in contrast to pharmacologic

doses of corticosteroids that, in the past, demonstrated no

difference or an adverse effect. A recent large multicenter

trial, however, demonstrated that physiologic replacement of

corticosteroids did not affect outcome, was associated with

adverse effects, and did not show that the cortisol response to

ACTH was helpful in identifying responders. It is recom-

mended that corticosteroids be given only in severe sepsis if

adrenal suppression is suspected (eg, recent administration

of corticosteroids, etomidate, and other drugs) or if the

patient fails to respond to fluids and vasoactive drugs.

A large trial comparing recombinant human activated

protein C (drotrecogin-alfa [activated]) with placebo in

patients with sepsis showed a statistically significant

decrease in mortality in the treatment group. A major risk

accompanying use of activated protein C is hemorrhage. In

one study, 3.5% of patients receiving activated protein C

had serious bleeding compared with 2.0% of those receiv-

ing placebo. Adjunctive treatment with activated protein C

should be considered in patients with sepsis with severe

organ compromise and the highest likelihood of death. The

mechanism of action is unknown, but activated protein C

may modulate coagulation and inflammation associated

with severe sepsis.

Dellinger RP et al, for the International Surviving Sepsis Campaign

Guidelines Committee: Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International

guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008.

Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327. [PMID: 18158437]

Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE: The pathophysiology and treatment of sep-

sis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:138–50. [PMID: 12519925]

Minneci PC et al: Meta-analysis: The effect of steroids on survival

and shock during sepsis depends on the dose. Ann Intern Med

2004;141:47–56. [PMID: 15238370]

Nguyen HB et al: Early lactate clearance is associated with

improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care

Med 2004;32:1637–42. [PMID: 15286537]

Opal SM et al: Systemic host responses in severe sepsis analyzed

by causative microorgansm and treatment effects of

drotrecogin-alfa (activated). Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:50–8.

[PMID: 12830408]

Rivers E et al: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe

sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1368–77.

[PMID: 11794169]

Russell JA: Management of sepsis. N Engl J Med 2006;355:

1699–1713. [PMID: 17050894]

Sprung CL et al: Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic

shock. N Engl J Med 2008;358:111–24. [PMID: 18184957]

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Patients present with cough, fever, and occasionally

pleuritic chest pain.

Chest x-ray shows pulmonary infiltrates.

Most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia

is Streptococcus pneumoniae.

INFECTIONS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL

363

General Considerations

Community-acquired pneumonia accounts for a large

number of hospitalizations each year and is the sixth lead-

ing cause of death in industrialized communities. Mortality

ranges from 12–40%, the latter number reflecting the death

rate in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

requiring critical care. It is crucial for the physician to rec-

ognize the high-risk patient, to initiate diagnostic proce-

dures, and to begin appropriate and prompt antimicrobial

therapy.

A number of risk factors for community-acquired pneu-

monia have been identified and include increasing age, alco-

holism, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, immunosuppression,

institutionalization, and underlying cardiac, pulmonary,

hepatic, renal, or neurologic disease. A meta-analysis evalu-

ating outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneu-

monia revealed 11 statistically significant factors associated

with mortality: male sex, diabetes mellitus, underlying neu-

rologic or neoplastic disease, pleuritic chest pain, hypother-

mia, tachypnea, hypotension, leukopenia, multilobar

infiltrates, and bacteremia. Increasing age and bacterial etiol-

ogy of the infection were strongly associated with mortality

as well. Patients with infections owing to Pseudomonas aerug-

inosa, S. aureus, and enteric gram-negative rods are at partic-

ularly high risk for increased morbidity and mortality.

Microbiologic Etiology

The most common organisms identified in community-

acquired pneumonia requiring intensive care hospitalization

are S. pneumoniae, Legionella, and Haemophilus influenzae,

with S. aureus included in some series. H. influenzae usually

occurs in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-

ease. S. aureus can cause severe pneumonia with disease

acquired either by aspiration or by hematogenous spread.

The former is seen in patients with decreased local host

defenses (eg, after influenza, laryngectomy, bronchiectasis, or

cystic fibrosis) or generalized decrease in immunity (eg, mal-

nutrition or immunosuppression). Hematogenous disease

typically is seen in injection drug abusers or patients with

indwelling intravascular catheters. Recently, community-

acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) has

become an important pathogen. It should be suspected in

any patient with gram-positive cocci in sputum and in

patients with necrotizing pneumonia without suspected

aspiration. Aerobic gram-negative rods such as E. coli and

Klebsiella species are uncommonly implicated as pathogens

in community-acquired pneumonia, but they can cause

severe pulmonary disease in patients of advanced age with

underlying illness who are colonized with these enteric

organisms. Therefore, when enteric organisms are recovered

from sputum samples, it can be difficult to tell if their pres-

ence is pathogenic or simply reflects colonization. P. a er u g i -

nosa traditionally has been considered a nosocomial

pathogen, although it can cause severe community-acquired

pneumonia. The physician should consider this organism in

a patient who has structural lung disease such as bronchiec-

tasis, was hospitalized recently, has recently received or is

currently receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics, or resides in

a nursing home.

Atypical pathogens, especially Legionella species, can

cause severe community-acquired pneumonia. More than

half of such cases are caused by L. pneumophila subgroup 1.

Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae typi-

cally cause tracheobronchitis or mild pneumonia and only

occasionally severe pneumonia.

Respiratory tract viruses are not commonly thought of as

agents of community-acquired pneumonia. However,

influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, and

parainfluenza virus all have been associated with severe

pneumonitis. In the appropriate host, varicella-zoster virus,

cytomegalovirus, hantavirus, and coronavirus (the causative

agent of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome [SARS])

should be considered.

In patients with episodes of altered level of consciousness

caused by seizures, other neurologic diseases, and substance

abuse, an aspiration syndrome should be considered.Aspiration

of gastric contents can cause a chemical pneumonitis—with or

without a polymicrobial pneumonia—that can lead to an

anaerobic lung abscess if left untreated.

Other less common causes of community-acquired

pneumonia include Pneumocystis jiroveci infection in the

patient with risk factors for HIV infection or receiving long-

term steroids or other immunosuppressive therapy. The

physician should maintain a high level of suspicion for

Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the appropriate host. In

patients with a history of travel to the appropriate areas,

endemic mycoses (eg, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces

dermatitidis, and Coccidioides immitis) should be consid-

ered. Infection with Coxiella burnetii, the etiologic agent

of Q fever, can present with a community-acquired pneu-

monia in a patient with a history of exposure to infected

cattle, sheep, goats, or parturient cats. Chlamydophila

psittaci similarly should be considered if a history of expo-

sure to psittacine birds is elicited. Despite aggressive diag-

nostic efforts, no etiologic agent is identified in over

50–60% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia.

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia and the

choice of empirical antibiotics depends on results of a

detailed history and physical examination of the patient,

microbiologic analysis of sputum, and review of the chest

radiograph.

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with severe community-

acquired pneumonia may report fever, chills, cough (either

dry or productive), dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain.

Nonspecific symptoms such as diarrhea, headache, myalgias,

or nausea and vomiting are often present. On physical exam-

ination, the typical patient with severe community-acquired

CHAPTER 15

364

pneumonia will have either fever or hypothermia accompa-

nied by tachycardia, tachypnea, abnormal breath sounds, and

possibly egophony or other evidence of lung consolidation. If

a pleural effusion is present, the patient may have decreased

breath sounds with dullness to percussion in the involved

hemithorax. The physical examination may provide clues to

guide empirical therapy. The presence of thrush or oral hairy

leukoplakia may suggest underlying HIV infection. Poor

dentition, caries, and gingival disease are often seen in

patients with aspiration pneumonia. Bullous myringitis is

seen occasionally with M. pneumoniae infection and also

may occur in patients with viral infection. The finding of a

new right-sided heart murmur should raise suspicion of

right-sided endocarditis. The skin should be examined care-

fully for any lesions that suggest one of the endemic mycoses.

B. Laboratory Findings—Routine laboratory studies should

be done, including a complete blood count; serum elec-

trolytes, urea nitrogen, and creatinine determinations; arterial

blood gas determinations; and chest x-ray. Because of their

high degree of specificity, blood cultures should be obtained

on all patients; 25% of patients with pneumococcal pneumo-

nia will be bacteremic. Pleural fluid collections, when present,

should be sampled to differentiate between a parapneumonic

effusion and a complicated effusion or empyema, the latter of

which would require definitive drainage. Pleural fluid should

be submitted for Gram stain, culture, cell count, pH, total

protein, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentration.

The Gram-stained smear of sputum may be the most

immediately helpful tool in determining empirical antibiotic

therapy. To ensure that an adequate specimen is obtained, the

stain should have 10 or fewer squamous epithelial cells and

more than 25 polymorphonuclear cells per high-power field.

Table 15–2 provides a guide to the probable pathogen based

on the Gram-stained smear of sputum (and other stains)

that can be done in an expeditious fashion. Legionella uri-

nary antigen is 80–95% sensitive for L. pneumophila group 1

and should be performed in appropriate patients.

Other more invasive methods of diagnosis are used in spe-

cial situations or when patients fail to respond despite appro-

priate empirical therapy. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with

bronchoalveolar lavage may assist in the diagnosis of pneu-

monia caused by P. jiroveci, M. tuberculosis, and certain fungi.

However, routine bacterial culture is not specific for the diag-

nosis of pneumonia caused by bacteria that can colonize the

respiratory tract. The specificity of this procedure can be

increased by quantitative cultures and cytologic examination

of the specimen for intracellular bacteria. The specificity of

bronchoscopy cultures may be increased by use of the

protected brush technique with quantitative cultures.

Bronchoscopy allows for direct inspection of the airways and

sampling from the site of infection. Percutaneous fine-needle

lung aspiration has been performed in some situations. This

procedure is the most sensitive and specific of all diagnostic

maneuvers; however, complications include bleeding and

pneumothorax, which may increase patient morbidity.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of severe community-acquired pneu-

monia is extensive. In addition to the many infectious causes of

pneumonia, diseases that can mimic community-acquired

pneumonia include cardiogenic pulmonary disease, ARDS,

pulmonary emboli with infarction, pulmonary hemorrhage,

and lung cancer. Other less common diseases are pneumonitis

owing to collagen-vascular diseases, radiation or chemical

pneumonitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, pul-

monary alveolar proteinosis, and occupational lung disease.

Treatment

A. Empirical Antibiotic Therapy—Because it is impossible

to cover all pathogens empirically, the physician must use the

available data to make an informed decision regarding ther-

apy. Table 15–3 provides a guide for treatment of pneumonia

according to pathogen. In most situations involving hospital-

ized patients, when no clues to etiologic agent can be

obtained from history, physical examination, or laboratory

data, empirical antibiotic therapy should consist of a third-

generation cephalosporin in combination with a macrolide

or a quinolone.

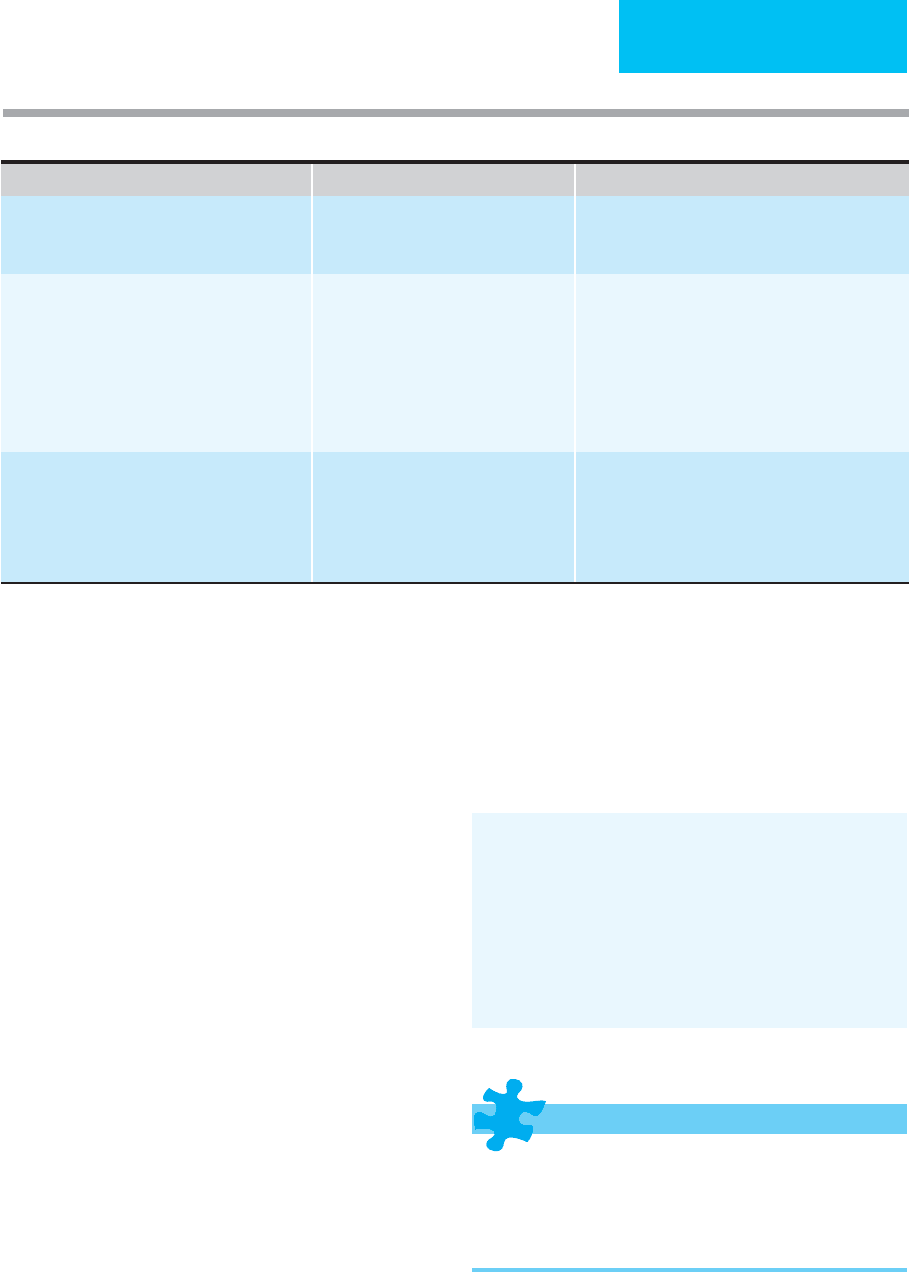

Staining Characteristic Potential Pathogen

Gram-positive diplococci

Gram-positive cocci in clusters

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Staphylococcus aureus

Gram-negative coccobacilli

Haemphilus influenzae

Moraxella catarrhalis

Gram-negative bacilli Enteric gram-negative rods

(

Escherichia coli, Klebsiella

pneumoniae, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

)

Mixed bacteria Oral contamination

Mixed aerobes and anaerobes

No organisms present Viruses

Mycoplasma penumoniae

Chlamydia pneumoniae

Coxiella burnetii

Legionella

species

Acid-fast stain-positive

Mycobacterium pneumoniae

Nocardia

species

KOH/calcofluor white

stain-positive

Coccidioides immitis

Histoplasma capsulatum

Blastomyces dermatitidis

Cryptococcus neoformans

Silver stain-positive

Pneumocystis jiroveci

Table 15–2. Sputum-guided potential pathogens for

severe community-acquired pneumonia.

INFECTIONS IN THE CRITICALLY ILL

365

B. Resistance Issues and Therapeutic Implications—

S. pneumoniae is the most common cause of community-

acquired pneumonia, and the emergence of penicillin-

resistant strains of this pathogen should be considered when

choosing empirical therapy for critically ill patients. There is

marked geographic variation in the rates of penicillin resist-

ance. Up to 35% of isolates in the United States are not fully

susceptible to penicillin, and up to 22% are highly resistant

to penicillin. However, resistance to third-generation

cephalosporins is less likely. In general, the levels of β-lactam

antibiotics that can be achieved in the lung and bloodstream

with intravenous therapy far exceed the minimum inhibitory

concentration (MIC) for pneumococci with intermediate

and high levels of resistance (as long as the MIC is <4 μg/dL).

Thus, in most cases, in the absence of meningitis, a third-

generation cephalosporin is adequate. Few data are available

regarding pneumococcal infections when the MIC for the

organism is greater than 4 μg/dL. Infection with an organism

with this level of resistance is associated with increased mor-

tality. Some authorities suggest using vancomycin, a car-

bapenem, one of the newer respiratory quinolones, or

possibly linezolid if infection with such a strain is suspected.

Risk factors for drug-resistant S. pneumoniae include

extremes of age, recent antimicrobial therapy, coexisting ill-

nesses, immunodeficiency or HIV-infection, attendance at a

day-care center or family member of a child attending a day-

care center, and institutionalization.

Dremsizov T et al: Severe sepsis in community-acquired pneu-

monia: When does it happen, and do systemic inflammatory

response syndrome criteria help predict course? Chest

2006;129:968–78. [PMID: 16608946]

Mandell LA et al: Infectious Diseases Society of America/American

Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of

community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis

2007;44:S27–72. [PMID: 17278083]

Oosterheert JJ et al: Severe community-acquired pneumonia:

What’s in a name? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2003;16:153–9. [PMID:

12734448]

Urosepsis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

The patient may be asymptomatic.

Flank or abdominal pain.

Pyuria and white blood cell casts.

Positive urine culture.

Patient Category Most Likely Causative Organisms

Empirical Antibiotic Choices

1

ICU patient

S. pneumoniae

Legionella

sp.

M. pneumoniae

Third-generation cephalosporin

2

plus

either

IV azithromycin or respiratory fluoroquinolone

3

ICU patient with increased risk for

P. aeruginosa

(recent antibiotic use, hospitalization, or structural

lung disease)

S. pneumoniae

Legionella

sp.

H. influenzae

C. pneumoniae

Enteric gram-negative rods

P. aeruginosa

Antipseudomonal, antipneumococcal β-lactam

4

plus

ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin (750 mg/day).

Or

Antipseudomonal, antipneumococcal β-lactam

4

plus

aminoglycoside and azithromycin

Or

Antipseudomonal, antipneumococcal β-lactam

4

plus

aminoglycoside and respiratory fluoroquinolone

3

ICU patient with increased risk for

S. aureus

(gram-positive cocci in clusters in a tracheal

aspirate or in an adequate sputum sample,

end-stage renal disease, injection drug use, prior

influenza, prior antibiotic therapy, necrotizing

pneumonia in absence of risks for aspiration.)

Community-acquired methicillin-resistant

S. aureus

(CA-MRSA)

Add

vancomycin or linezolid

1

Initial empirical therapy. Changes should be based on results of microbiologic studies and clinical response.

2

Third-generation cephalosporin (eg, ceftriaxone or cefotaxime).

3

Fluoroquinolone with increased activity against S. pneumoniae (eg, levofloxacin).

4

Cefipime, piperacilllin-tazobactam, imipenem, or meropenem.

Table 15–3. Empirical antibiotic therapy for community-acquired pneumonia in patients requiring ICU admission.

CHAPTER 15

366

General Considerations

In the United States, acute pyelonephritis accounts for over

100,000 hospitalizations each year. The physician must be

alert for complications such as underlying immunosuppres-

sion, urinary tract obstruction, and intrarenal or perinephric

abscess formation. When hypotension or other signs of sep-

sis are present, patients should be admitted to the ICU for

appropriate hemodynamic monitoring and management.

Pathophysiology

There are two primary routes by which bacteria invade the

urinary system. In what is by far the most common route of

infection, bacteria gain access to the bladder via the urethra.

Urinary tract infections are common in women because the

relatively short female urethra allows retrograde passage of

bacteria into the bladder. In contrast, urinary tract infection

in men is a rare event in the absence of a urethral catheter or

unless there is obstruction of the urethra (eg, prostatic hyper-

plasia), preventing adequate bladder drainage. Once bacteria

have entered the bladder, they may under some circumstances

ascend the ureters to the renal pelvis and parenchyma. This

process is facilitated by the presence of vesicoureteral reflux.

For example, in the renal transplant patient, the transplanted

kidney is placed in the pelvis with the ureter surgically

implanted in the bladder; as a result, simple cystitis frequently

leads to acute transplant pyelonephritis.

Infection of the urinary tract by hematogenous spread is

a much less common occurrence. Staphylococcal bacteremia

or endocarditis can lead to seeding of renal parenchyma

with subsequent abscess formation. However, experimen-

tally produced gram-negative bacteremia rarely leads to

acute pyelonephritis.

Microbiologic Etiology

The majority (70–95%) of cases of community-acquired

acute urinary tract infections are caused by E. coli, with

Staphylococcus saprophyticus, enterococci, Proteus mirabilis,

Klebsiella species, and Enterobacter species identified in

most of the remaining cases. The list of etiologic agents is

modified by factors such as use of indwelling urinary

catheters, residence in an institutionalized setting, urinary

tract instrumentation, immunosuppression, or recent broad-

spectrum antibiotic administration. In any of these settings,

multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli, coagulase-negative

staphylococci, or Candida species may be responsible for

infection.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with urinary tract infec-

tions as the source of sepsis may present with localizing

symptoms such as flank pain or dysuria. However, many

patients present with nonspecific complaints, such as nausea,

vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, and chills. Physical

examination may detect the presence of flank tenderness. An

indwelling bladder catheter should trigger a prompt evalua-

tion of the urinary tract for the source of sepsis.

B. Laboratory Findings—Routine laboratory tests such as a

complete blood count and chemistry panel should be

obtained. Microscopic evaluation of a urine specimen is the

most important diagnostic test, typically revealing hematuria,

proteinuria, and pyuria (≥10 leukocytes/μL of urine), often

with white blood cell casts. Gram stain of the urine should be

performed; the presence of one organism per oil-immersion

field correlates with 10

5

bacteria per milliliter of urine or

more, with a sensitivity and specificity approaching 90%. The

presence of 5 or more organisms per oil-immersion field

increases the specificity to 99%. Additionally, determining the

morphology of the infecting bacteria (ie, gram-negative bacil-

lus or gram-positive cocci) may be used to direct empirical

therapy. Identification of the pathogen and the results of

antimicrobial susceptibility testing are usually available

within 48 hours, allowing tailoring of antimicrobial therapy.

Any patient sick enough to warrant hospitalization should

have blood cultures sent. A renal ultrasound examination or an

abdominal CT scan should be obtained in any patient with sus-

pected upper urinary tract obstruction admitted to the ICU.

C. Complications—Possible complications of acute

pyelonephritis include urosepsis, perinephric abscess,

intrarenal abscess, urinary tract obstruction, and emphyse-

matous pyelonephritis. In general, any patient who appears

toxic or has persistent fever or positive blood cultures beyond

the third day of appropriate therapy should undergo investi-

gation for obstruction, abscess, or other complications.

Perinephric abscesses usually are confined to the per-

inephric space by Gerota’s fascia but may extend into the

retroperitoneum. Thirty percent of patients with perinephric

abscess have a normal urinalysis, and up to 40% have a ster-

ile urine culture. Intrarenal abscess is usually a complication

of systemic bacteremia; thus the etiologic agent is often a

Staphylococcus. A plain film of the abdomen may reveal an

abdominal mass, an enlarged indistinct kidney shadow, or

loss of the psoas margin. Rapid diagnosis of perinephric or

intrarenal abscess can be made by renal ultrasound, CT scan,

or MRI. Renal ultrasound can detect an abscess once it

reaches 2–3 cm in size, whereas CT scan and MRI are more

sensitive, detecting abscesses as small as 1 cm in diameter.

Definitive treatment requires drainage of larger abscesses,

either by percutaneous access or open surgical drainage, with

concomitant antimicrobial therapy.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a rare complication

of urinary tract infections seen in patients with diabetes,

papillary necrosis, renal obstruction, or renal insufficiency.

The infecting organism is typically E. coli, Klebsiella

species, or Proteus species. Mortality is high, approaching

50% despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Diagnosis

is easily made with a plain film or with the more sensitive

CT scan of the abdomen; both will reveal gas in the renal

parenchyma.