Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GASTROINTESTINAL FAILURE IN THE ICU

347

should be used. With the interference of bowel gas, examina-

tion of the retroperitoneum by ultrasonography is often lim-

ited initially. However, valuable information concerning the

biliary tree may be obtained. CT scans have low sensitivity

for the detection of gallstones but generally are superior to

ultrasonography for the delineation of retroperitoneal dis-

ease processes.

D. Estimation of Severity and Determination of

Prognosis—Determination of the severity of acute pancreati-

tis based on clinical evaluation alone is accurate in only

35–40% of patients. A number of scoring methods have been

devised for objective assessment of the severity and predic-

tion of morbidity and mortality. These scoring techniques are

useful in ensuring early institution of appropriate manage-

ment and in tracking physiologic progress. However, sickness

scoring systems are of limited use in making management

decisions for individual patients. Their most valuable contri-

bution in acute pancreatitis may be in assessment of new

treatment strategies and evaluation of quality assurance.

Initial scoring systems for acute pancreatitis were developed

prior to the widespread availability of CT scanning and are

based on multiple clinical and biochemical parameters. They

include Ranson’s Early Prognostic Signs, Imrie’s Prognostic

Criteria, Simplified Prognostic Criteria, the Glasgow Criteria,

and the APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health

Evaluation) scoring system. These systems have various draw-

backs. Most are complex and difficult to remember, extensive

data collection and computation are required, and lack of data

on all parameters occurs frequently. Completed scores may not

be available during initial management.

Ranson’s method (Table 14–1) is the standard against

which other scoring systems are judged. A score of less than

2 based on Ranson’s criteria indicates mild disease with a

good prognosis. A score greater than 6 correlates with a mor-

tality rate of 20% and a complication rate of 80%. Imrie’s

system is a simplification of the original Ranson criteria and

is popular in the Commonwealth countries. The Simplified

Prognostic Criteria (SPC) with only four parameters is easier

to remember. Two SPC signs are the equivalent of six or more

Ranson signs. As a general guideline, all patients with more

than three of Ranson’s criteria or APACHE II scores greater

than 8 should be managed the ICU.

With the advent of routine organ imaging in acute pan-

creatitis, scoring systems based on the CT appearances of the

primary disease process have been developed. These are at

least as good predictors of severity and outcome as any of the

physiologic scoring systems and have the advantage of

immediate availability. Multiple scans may be necessary to

ensure the accuracy of this technique because the CT appear-

ance may change with time.

Another system, based on the quality and quantity of peri-

toneal fluid that can be recovered by lavage, also has been

described. It has the disadvantage of requiring an invasive pro-

cedure and is not used widely except by clinicians who favor

peritoneal lavage as a treatment measure in acute pancreatitis.

E. Identification of Pancreatic Necrosis—The most seri-

ous local complication of acute pancreatitis is pancreatic

necrosis, which, if infection occurs and treatment is not pro-

vided, carries a 100% mortality rate. Following initial resus-

citation, identification and delineation of this process are the

primary aims of management because timely operation will

reduce the mortality rate significantly.

Clinical signs include increasing pain and abdominal

distention. Progressive physiologic derangement and

increasing systemic toxicity are observed with necrosis.

Physiologic monitoring by repeated objective scoring

assessments may be useful to record progressive deteriora-

tion at this stage.

Identification and assessment of pancreatic necrosis are

based on a combination of clinical appraisal, sickness scor-

ing, measurement of serum factors, organ imaging, and fine-

needle aspiration biopsy of the pancreas. Several serum

factors can be correlated with pancreatic necrosis.

Biochemical parameters include a fall in α

2

-macroglobulin

and C3 and C4 complement factors and a rise in α

2

-antipro-

tease, C-reactive protein, and pancreatic ribonuclease. These

parameters lack absolute sensitivity and at best only comple-

ment other methods.

CT scanning is becoming established as the best means of

assessment of pancreatic necrosis. Enhanced physiologic

imaging using high-resolution contrast-enhanced scanning

techniques increases the sensitivity and specificity of this

technique and has been reported to clearly establish the

presence and extent of pancreatic necrosis. The initial CT

scan should be performed for diagnosis and estimation of

disease severity. Repeated scanning is necessary in all but the

mildest cases to monitor local progression of disease.

Subsequent scans may be scheduled after 1 week if the clin-

ical course gradually improves. Patients who fail to respond

Criteria present initially

Age >55 years

White blood cell count >16,000/μL

Blood glucose >200 mg/dL

Serum LDH >350 IU/L

AST (SGOT) >250 IU/L

Criteria developing during first 24 hours

Hematocrit fall >10%

BUN rise >8 mg/dL

Serum Ca

2+

<8 mg/dL

Arterial P

O

2

<60 mm Hg

Base deficit >4 meq/L

Estimated fluid sequestration >6000 mL

∗

Morbidity and mortality rates correlate with the number of criteria

present. Mortality rates correlate as follows: 0–2 criteria present =

2%; 3 or 4 = 15%; 5 or 6 = 40%; 7 or 8 = 100%.

Table 14–1. Ranson’s criteria of severity of acute

pancreatitis.

∗

CHAPTER 14

348

after adequate initial resuscitation or show evidence of wors-

ening clinical status require earlier evaluation and are candi-

dates for scanning with dynamic vascular enhancement in an

attempt to establish the presence and extent of the necrosis.

F. Needle Aspiration—Needle aspiration of pancreatic and

peripancreatic collections under CT control is becoming

accepted as a means of identification of superinfection. At

least 40% of necrotic collections are found to be infected at

the time of initial management. The most common organ-

ism is Escherichia coli, but a wide variety of gram-positive

and gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic organisms (as sin-

gle or mixed cultures) has been isolated. Aspiration culture

results may be used as a guide to antibiotic selection.

G. Systemic Considerations—Respiratory failure is com-

mon in patients with moderate to severe acute pancreatitis.

Indium-labeled leukocyte scintiscans demonstrate early

margination of the leukocytes in the lungs. The quantitative

deposition correlates with other prognostic indicators. This

is identical to the pattern seen in sepsis-related acute respira-

tory distress syndrome (ARDS). Assessment of ventilation

and gas exchange should be included in the initial evaluation.

Patients may have clinical evidence of bilateral pleural effu-

sions with or without evidence of underlying atelectasis. It is

often useful to include a few CT images of the lung bases at

the same time as the pancreatic scanning. Such lung sections

clearly demonstrate the pulmonary involvement, which may

be more significant than the chest x-ray suggests. In the more

fulminant cases, the clinical picture is one of typical ARDS. A

marked rise in liver aminotransferase (AST >1000 units/L)

suggests the possibility of ischemic hepatitis. This diagnosis

should be included in the differential in evaluation of a

patient suspected of having gallstone pancreatitis and per-

sistent choledocholithiasis. In its more severe form, ischemic

hepatitis may be associated with other metabolic derange-

ments, including a rise in bilirubin. Gradual recovery usually

can be expected.

A low Glasgow Coma Score may be observed for several

reasons in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. The use of

sedation and opioids for pain relief may modify cerebral

function, and catastrophic illness is often associated with

acute organic brain syndrome. Pancreatic encephalopathy

also has been described as a separate entity. It is attributed to

the release of pancreatic lipases, but the evidence for this

view is inconclusive. MRI demonstrates patchy white matter

abnormalities that resemble the plaques seen in multiple

sclerosis.

Treatment

Critical care of the patient with acute pancreatitis consists

essentially of maintaining adequate perfusion and oxygen

delivery to essential organs during resolution of the primary

disease process. Early and aggressive resuscitation reduces

the mortality rate by reducing the incidence of multisystem

organ failure.

A. Fluid Resuscitation and Physiologic Monitoring—

The degree of intravascular fluid depletion is difficult to

gauge accurately in patients with acute pancreatitis. Tissue

fluid shifts related to systemic release of vasoactive toxins and

severe retroperitoneal losses may be dramatic. As much as

10–20 L of replacement fluid may be required in the first

24 hours. Replacement by crystalloid is the fluid of choice.

Colloid is used only in patients in whom the albumin is dan-

gerously low. Depending on the clinical severity, blood

transfusion should be considered when the hemoglobin is

less than 10 g/dL. The use of fresh-frozen plasma for sys-

temic deactivation of proteases has provided apparent bene-

fit in empirical trials. Controlled studies, however, have failed

to provide objective evidence of an improvement in out-

come, and routine use of fresh-frozen plasma should await

further evaluation.

As in any shock state, adequacy of fluid replacement is

assessed by measurement of central venous or pulmonary

arterial wedge pressure, aiming for values at least 10 mm Hg

above the intrathoracic pressure. In patients in whom positive-

pressure ventilation is being used, the systemic venous

pressure or the pulmonary arterial wedge pressure should

be at least 10 mm Hg higher than the ventilatory positive

end-expiratory pressure.

The adequacy of fluid replacement can be further

assessed by measurement of the response to repeated fluid

challenges with 250–500 mL of balanced salt solution. If cen-

tral filling pressures are sufficient, such challenges will be fol-

lowed by a sustained rise in central venous pressure of 3–5

mm Hg. Once filling pressures are optimized, the increment

in cardiac output in response to further fluid replacement is

minimal, and the patient should be kept stable at this level.

Successful fluid resuscitation should be accompanied by

improved peripheral perfusion, as indicated by limb temper-

ature, peripheral pulse volume, arterial blood pressure, uri-

nary output, and mixed venous oxygen. Low mixed venous

oxygen tension (P

–

v

O

2

<40 mm Hg) indicates that the perfu-

sion state is inadequate. If central filling pressures have been

optimized, myocardial dysfunction should be suspected.

B. Inotropic Support—Echocardiographic evaluation is

useful for differentiation of the hypovolemic state from the

hypocontractile state. In the former, heart size is normal or

less than normal, and there is evidence of vigorous wall

motion. In the latter, there is usually discernible chamber

enlargement and segmental or global hypokinesia.

If myocardial hypocontractility is diagnosed, inotropic

support should be instituted. Strict guidelines for choice of

inotropic agents are not available. In general, however, for

patients in whom persistent hypotension dominates, an

incrementally increased infusion of dopamine titrated

against blood pressure is the preferred initial strategy. In sit-

uations where tissue perfusion remains poor despite ade-

quate arterial pressures, inotropic agents without prominent

α-adrenergic effects such as dobutamine may be preferable.

Irrespective of the agent used, the clinical objective is

GASTROINTESTINAL FAILURE IN THE ICU

349

improvement of organ perfusion, and mixed venous oxy-

genation should be specifically evaluated rather than relying

solely on monitoring of arterial blood pressure.

C. Respiratory Support—Patients with significant hypoxia

(Pa

O

2

<60 mm Hg) despite high inspired oxygen or clinical

evidence of compromised ventilation (respiratory rate of >

30 breaths/min or dyskinetic breathing pattern) should be

considered for early intubation and mechanical ventilatory

support. Sedation, analgesia, and mechanical ventilation

improve overall cardiopulmonary performance.

D. Renal Support—Impaired renal function—indicated by

rising serum urea nitrogen and creatinine or oliguria with

frank acute tubular necrosis—is seen often in severe acute

pancreatitis. Early and adequate fluid replacement minimizes

the risk, but renal function may continue to deteriorate

despite adequate hemodynamic resuscitation. Low-dose

dopamine may increase renal blood flow, minimizing the

ischemic insult.

Fortunately, the prognosis for renal function is good, and

in most cases temporary hemodialysis or hemofiltration will

maintain adequate homeostasis until renal function returns.

Once acute tubular necrosis has become established, it is

important to avoid secondary ischemic insults, which may

result in acute cortical necrosis and permanent loss of renal

function.

E. Nutrition—Acute pancreatitis is a hypermetabolic state

similar to sepsis. Retroperitoneal edema may contribute to

prolonged small bowel dysfunction and make enteral nutri-

tional support impossible. This, along with ongoing negative

nitrogen balance, mandates the institution of total parenteral

nutrition. While early institution of total parenteral nutrition

is theoretically desirable, these patients are variably intoler-

ant of the high metabolic loads. The degree of insulin resist-

ance is often extreme, with high-dose insulin infusions required

to stabilize serum glucose levels at less than 150 mg/dL. Early

institution of total parenteral nutrition is not critical, and in

the hemodynamically unstable patient, delayed introduction

is advised.

It has been proposed that hyperlipidemia may in itself

stimulate the pancreas and help perpetuate the inflammatory

process. For this reason, total parenteral nutrition regimens

with reduced fat content have been advocated. There is, how-

ever, no objective evidence that patients with acute pancre-

atitis are adversely affected by customarily used lipid

regimens, and the use of nutritional formulas low in lipids is

a matter of personal choice.

Evidence of the benefit of total parenteral nutrition for

modification of the disease process within the pancreas is not

yet available. Nor is there real evidence to suggest the superi-

ority of any particular regimen for the maintenance of basic

nutrition.

Patients with acute pancreatitis do appear to have a height-

ened susceptibility to intravenous line infections, and meticu-

lous care of catheters is required. Dedicated ports exclusively

for total parenteral nutrition infusions—with meticulous

care during line changes—may help to reduce infection rates.

F. Other Modalities—Little can be done to substantially

modify the inflammatory process within the pancreas.

Various interventions have been proposed, but none has

been shown to have substantial value. Steroids are not indi-

cated. Inhibitors of pancreatic function such as glucagon and

octreotide have been used without demonstrable benefit.

Antiproteases such as aprotinin also have lacked obvious

therapeutic effect and now have been largely abandoned.

The nature and extent of surgery depend on appraisal of

the radiologic appearance of the pancreas and the physio-

logic status of the patient. Peritoneal lavage, manipulation of

the biliary tree, and pancreatic procedures, as well as opera-

tive management of complications, all have a place in the

operative management of severe acute pancreatitis. Optimal

timing of any procedure is critical and is based largely on

clinical judgment.

Once the patient with severe acute pancreatitis is resusci-

tated, efforts must be directed toward the detection and

management of pancreatic necrosis. Dynamic contrast-

enhanced CT scanning is the most accurate method for eval-

uating pancreatic ischemia and also can aid in planning

operative treatment.

1. Peritoneal and retroperitoneal lavage—This rela-

tively noninvasive procedure was first advocated in 1965 and

was widely adopted thereafter. However, subsequent con-

trolled trials and standardization of patient selection showed

no significant difference in overall mortality rates. A more

recent trial of therapeutic peritoneal lavage for 7 days

reported a reduction in both the incidence and mortality rate

of pancreatic sepsis in patients with severe acute pancreatitis.

Some now advocate continuous lavage with 2-L exchanges

performed every hour. A modified balanced salt solution is

usually used.

Retroperitoneal lavage with aggressive irrigation has

avoided surgery and treated sepsis in a significant number of

patients.

2. Biliary procedures—Overwhelming evidence of the

association of choledocholithiasis with gallstone pancreatitis

prompted evaluation of the role of removal of common bile

duct stones in the management of acute pancreatitis. Up to

95% of patients with gallstone pancreatitis pass a gallstone in

the feces during the course of the illness. Choledocholithiasis

can be demonstrated in approximately 70% of these patients

within the first 48 hours of presentation, with the rate of

stone detection falling off rapidly thereafter.

Initial experience with urgent cholecystectomy or chole-

cystostomy with choledochostomy in acute pancreatitis

demonstrated a 72% common duct stone retrieval rate and a

2% mortality rate. However, these results were difficult to

replicate and were reported prior to the general use of scor-

ing systems to standardize illness severity and prognosis in

the management of patients with acute pancreatitis. Early

CHAPTER 14

350

definitive surgery in the acute phase of acute pancreatitis car-

ries unacceptable morbidity and mortality rates. However,

results suggest that early ERCP and endoscopic sphinctero-

tomy may have a favorable impact on survival in patients

with severe disease. Patient selection for ERCP and the inher-

ent risks and timing of this procedure in the very sick patient

need to be considered prior to adoption of this policy.

Ascending cholangitis in association with acute pancreatitis

is ideally treated by ERCP and sphincterotomy. Most sur-

geons would advocate semielective cholecystectomy once the

patient has recovered from the acute event—ideally, during

the same hospital admission.

3. Necrosectomy—This operation, involving empirical

debridement of devitalized pancreatic tissue, has gradually

become the treatment of choice in patients with severe

necrotizing pancreatitis. It has replaced formal pancreatic

resection, which carries a persistently high mortality rate.

The nonanatomic basis of this approach makes the outcome

of surgery particularly dependent on optimal timing of oper-

ation. Clinically detectable separation of necrotic and viable

tissue is best seen after 7 days, and patients in whom the ini-

tial operation can be delayed for as long as possible have an

overall lower mortality rate. Minimal debridement should be

planned if earlier operation is mandated by deteriorating

condition of the patient.

In many cases, several operations are required for com-

plete debridement because demarcation progresses over a

period of time. Attempted resection of nondemarcated tissue

to avoid multiple laparotomies is associated with increased

morbidity and mortality rates. The use and placement of

drains and the value of pancreatic bed lavage have lowered

the mortality of this condition. Pancreatic fistulas should be

managed by external drainage in the acute setting.

Management of the abdominal wall in the intervals

between multiple, closely timed laparotomies is also a matter

of choice for the surgeon. Vertical incisions with the use of

zipper closure techniques or horizontal incisions with isola-

tion of the supracolic compartment and an open wound

have been advocated. If the abdomen is left open, paralysis of

the patient is mandatory to prevent evisceration until early

adhesions contain the abdominal contents.

Minimally invasive necrosectomy in the form of aggres-

sive irrigation with fluoroscope-guided removal of tissue

with forceps and snares can buy time as well as be the defin-

itive procedure.

Standard laparoscopy with debridement of the retroperi-

tonium, cholecystectomy and splenectomy, endoscopic

transgastric and transduodenal retroperitoneoscopy and

debridement, and retroperitoneoscopy via either of the

flanks are all being evaluated as procedures that can be per-

formed on patients not fit for standard laparotomy.

4. Enteric fistulas—The massive retroperitoneal inflam-

mation associated with acute pancreatitis may lead to vascu-

lar complications. These include thrombosis and aneurysm

formation, with the former being the most common. The

middle colic vessels supplying the transverse colon are espe-

cially at risk, although gastric, duodenal, and small bowel fis-

tulas also have been described. If necrosectomy is required,

consideration should be given to examination of the trans-

verse colon. If evidence of ischemia is present, elective termi-

nal ileostomy at the time of first laparotomy may be valuable.

Other enteric fistulas are investigated and managed in rou-

tine fashion. One must be alert to this possibility to avoid dan-

gerous delays in diagnosis.

5. Bleeding—Catastrophic bleeding is difficult to manage

surgically because the inflamed pancreatic bed makes delin-

eation of anatomy and accurate dissection hazardous.

Embolization of the bleeding vessel by angiographic tech-

niques is probably the treatment of choice. Bleeding from

erosion into the splenic artery or other vessels may be life-

threatening.

6. Pancreatic abscess—Pancreatic abscess occurs with

delayed infection of limited pancreatic necrotic tissue that

has progressed beyond demarcation to liquefaction and iso-

lation. It is differentiated from infected necrosis by its

delayed presentation (4–6 weeks). Abscesses are best diag-

nosed by CT scan. The value of percutaneous CT-guided

catheter drainage in comparison with laparotomy has not

been established.

7. Pancreatic pseudocyst—Pancreatic pseudocysts form

by one of two mechanisms. Following acute pancreatitis,

extravasation of pancreatic enzymes produces necrosis of

surrounding tissues and forms a sterile collection of fluid

that is not reabsorbed as the inflammatory process subsides.

If the fluid collection becomes infected, a pancreatic abscess

results. If not, the fluid is retained by the surrounding

organs as a pseudocyst. The second mechanism typically fol-

lows trauma and is caused by ductal obstruction that leads

to a retention cyst. Pseudocysts occur in about 2% of all

cases of acute pancreatitis, and over 85% are singular.

Pseudocyst formation presents several weeks after the

episode of acute pancreatitis, making de novo presentation

in the ICU somewhat uncommon. However, patients are fre-

quently readmitted to a critical care facility when increased

epigastric pain, fever, and amylase elevation occur after ini-

tial therapy for pancreatitis. Pain is the most common find-

ing, but a few patients have a palpable mass, jaundice, or

weight loss. A CT scan is the procedure of choice for estab-

lishing the diagnosis, although serial ultrasonography is use-

ful for determining changes in the size of the pseudocyst.

Infection, rupture, and hemorrhage are the major complica-

tions of pancreatic pseudocysts. Many resolve sponta-

neously, although internal drainage via cystoenterostomy

may be required; endoscopic transgastric cystostomy is

being evaluated. Critical care management is similar to that

for acute pancreatitis, with particular requirements for par-

enteral nutritional support and treatment of infectious

complications.

GASTROINTESTINAL FAILURE IN THE ICU

351

Acosta JM, Ledesma CL: Gallstone migration as a cause of acute

pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 1974;290:484–7. [PMID: 4810815]

Acosta JM et al: Early surgery for acute gallstone pancreatitis:

Evaluation of a systematic approach. Surgery 1978;83:367–70.

[PMID: 635772]

Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS: Assessment of severity in acute pancre-

atitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:1385–91. [PMID: 1928029]

Balthazar EJ et al: Acute pancreatitis: Value of CT in establishing

prognosis. Radiology 1990;174:331–6. [PMID: 2296641]

Beger HG et al: Necrosectomy and postoperative local lavage in

necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1988;75:207–12. [PMID:

3349326]

Blamey SL et al: Prognostic factors in acute pancreatitis. Gut

1984;25:1340–6. [PMID: 6510766]

Block S et al: Identification of pancreas necrosis in severe acute

pancreatitis: Imaging procedures versus clinical staging. Gut

1986;27:1035–42. [PMID: 3530895]

Boon P et al: Pancreatic encephalopathy: A case report and review

of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1991;93:137–41.

[PMID: 1652395]

Cotton PB: Pancreas divisum. Pancreas 1988;3:245–7. [PMID:

3387417]

De Coninck B et al: Scintigraphy with indium–labelled leukocytes

in acute pancreatitis. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 1991;54:176–83.

[PMID: 1755270]

Di Carlo V et al: Hemodynamic and metabolic impairment in acute

pancreatitis. World J Surg 1981;5:329–39. [PMID: 7293195]

Fink AS et al: Indolent presentation of pancreatic abscess. Arch

Surg 1988;123:1067–72. [PMID: 3415457]

Freeny PC: Angio-CT diagnosis and detection of complications of

acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 1991;38:109–15.

[PMID: 1855765]

Friedman AD et al: Pancreatic enlargement in alcoholic pancreati-

tis: Prevalence and natural history. J Clin Gastroenterol

1991;6:666–72. [PMID: 1722232]

Imrie CW et al: A single-centre double-blind trial of Trasylol ther-

apy in primary acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1978;65:337–41.

[PMID: 348250]

Imrie CW et al: Arterial hypoxia in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg

1977;64:185–8. [PMID: 890262]

Kivisaari L et al: A new method for the diagnosis of acute haemor-

rhagic-necrotizing pancreatitis using contrast enhanced CT.

Gastrointest Radiol 1984;9:27–30.

Kloppel G et al: Human acute pancreatitis: Its pathogenesis in the

light of immunocytochemical and ultrastructural findings of

acinar cells. Virchows Arch [A] 1986;409:791–803.

Larvin M, Chalmers AG, McMahon MJ: Dynamic contrast enhances

computed tomography: A precise technique for identifying and

localizing pancreatic necrosis. Br Med J 1990;300:1425–8.

Leese T et al: Multicentre clinical trial of low volume fresh frozen

plasma in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1987;74:907–11. [PMID:

2444309]

Malfertheiner P, Kemmer TP: Clinical picture and diagnosis of

acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 1991;38:97–100.

[PMID: 1855780]

McKay AJ et al: Is an early ultrasound scan of value in acute pan-

creatitis? Br J Surg 1982;69:369–72. [PMID: 7104603]

Meyer P et al: Role of imaging technics in the classification of acute

pancreatitis. Dig Dis 1992;10:330–34. [PMID: 1473285]

Moulton JS: The radiologic assessment of acute pancreatitis and its

complications. Pancreas 1991;6:S13–22.

Neoptolemos JP et al: ERCP findings and the role of endoscopic

sphincterotomy in acute gallstone pancreatitis. Br J Surg

1988;75:954–60. [PMID: 3219541]

Neoptolemos JP et al: The role of clinical and biochemical criteria

and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the

urgent diagnosis of common bile duct stones in acute pancre-

atitis. Surgery 1987;100:732–42. [PMID: 2876528]

Pemberton JH et al: Controlled open lesser sac drainage for pan-

creatic abscess. Ann Surg 1986;203:600–4. [PMID: 3718028]

Pisters PWT, Ranson JHC: Nutritional support for acute pancre-

atitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1992;175:275–84. [PMID: 1514164]

Pitchumoni CS, Agarwal N, Jain NK: Systemic complications of acute

pancreatitis.Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:597–606. [PMID: 3287900]

Planche NE et al: Effects of intravenous alcohol on pancreatic and

biliary secretion in man. Dig Dis Sci 1982;27:449–53. [PMID:

7075433]

Ranson JH et al: Prognostic signs and nonoperative peritoneal

lavage in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1976;143:

209–19. [PMID: 941075]

Ranson JH et al: Prognostic signs and the role of operative man-

agement in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet

1974;139:69–81. [PMID: 4834279]

Ranson JH et al: Respiratory complications in acute pancreatitis.

Ann Surg 1974;179:557–66. [PMID: 4823837]

Safrany L, Cotton PB: A preliminary report: Urgent duodeno-

scopic sphincterotomy for acute gallstone pancreatitis. Surgery

1981;89:424–8. [PMID: 7209790]

Saluja AK et al: Pancreatic duct obstruction in rabbits causes diges-

tive zymogen and lysosomal enzyme colocalization. J Clin

Invest 1989;84:1260–6. [PMID: 2477393]

Schmidt E, Schmidt FW: Advances in the enzyme diagnosis of pan-

creatic diseases. Clin Biochem 1990;23:383–94. [PMID: 2253333]

Stanten R, Frey CF: Comprehensive management of acute necro-

tizing pancreatitis and pancreatic abscess. Arch Surg

1990;125:1269–74. [PMID: 2222168]

Steer ML: How and where does acute pancreatitis begin? Arch Surg

1992;127:1350–3. [PMID: 1280081]

Vincent JL, De Backer D: Initial management of circulatory shock

as prevention of MSOF. Crit Care Clin 1989;5:369–78. [PMID:

2650823]

Werner J, Feuerbach S, Uhl W, Buchler MW: Management of acute

pancreatitis: From surgery to interventional intensive care. Gut

2005;54:426-436. [PMID: 15710995]

Bowel Obstruction

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Colicky abdominal pain.

Emesis.

Dehydration.

Peristaltic “tinkles and rushes” on abdominal auscultation.

Air-fluid levels on abdominal x-ray.

CHAPTER 14

352

General Considerations

Bowel obstructions are common among critically ill patients

and may be the underlying reason for ICU admission or may

develop as part of another disease process. Obstructions of

the small bowel may be mechanical or paralytic. Mechanical

obstructions occur when a physical impediment to the abo-

ral progress of intestinal contents is present. Paralytic ileus

(ie, functional obstruction) occurs when an underlying dis-

ease process interferes with normal peristalsis. Metabolic

derangements, neurogenic causes, drug effects, and peritoni-

tis are the most common causes of paralytic ileus.

Mechanical obstruction can be divided into simple obstruc-

tions, involving only the bowel lumen, and strangulated

obstructions, which impair blood supply and lead to necro-

sis of the intestinal wall. A simple obstruction takes place at

just one location. When the bowel lumen is occluded in two

or more locations, a closed-loop obstruction is created.

Closed-loop obstructions are often associated with strangu-

lation because blood supply may be compromised.

Adhesions from previous abdominal surgery are the most

common cause of small bowel obstruction. Onset is usually

insidious, with abdominal bloating and crampy abdominal

pain. External hernias through the abdominal wall that

become incarcerated are the second most common cause of

small bowel obstruction. Internal hernias also can occur at

the obturator foramen, through the diaphragm, or at the

foramen epiploicum (Winslow). Defects caused by surgery,

such as those adjacent to stomas, also are potential sites for

the formation of internal hernias.

Neoplasms within or extrinsic to the small bowel may

produce obstruction directly or by mass effect. Such tumors

may serve as the lead point for an intussusception. Although

rare in adults, intussusception may occur without a lesion

serving as a lead point.

Volvulus is produced when mobile bowel rotates around

a fixed point. This is frequently the consequence of congeni-

tal abnormalities or acquired adhesions. Obstruction typi-

cally occurs abruptly and leads to intestinal strangulation if

not relieved quickly. Sigmoid and cecal volvulus of the colon

is significantly more common than small bowel volvulus.

Other less common causes of small bowel obstruction

include gallstone ileus, ingested foreign bodies, inflammatory

bowel disease, stricture owing to radiation therapy, cystic

fibrosis, and posttraumatic hematoma. Gallstone ileus occurs

in patients with cholelithiasis who develop a fistula between

the gallbladder and a loop of small bowel, typically the duo-

denum. As the gallstone progresses distally, it produces a pat-

tern of intermittent small bowel obstruction at different

levels, referred to as “tumbling” obstruction. Air in the biliary

tree on abdominal x-ray is the key to the diagnosis.

When the small bowel is obstructed, distention with gas

and fluid occurs proximally. Swallowed air is the major cause

of distention. This is due to the high nitrogen content in

room air, which is not well absorbed by the mucosa. Bacterial

fermentation produces other gases as well, such as methane.

Inflammation leads to transudation of fluid from the extra-

cellular space into the bowel lumen and peritoneal cavity. As

the proximal lumen distends and fluid accumulates, the bidi-

rectional flow of salt and water is disrupted, and secretion is

enhanced. Other substances such as prostaglandins and

endotoxins released by bacterial proliferation in the static

lumen further the process. Fluid losses may be so severe that

hypotension results and ultimately may lead to cardiovascu-

lar collapse unless recognized and treated expeditiously.

Vomiting usually accompanies small bowel obstruction and

becomes progressively more feculent as the illness progresses.

Peristaltic “rushes” are the auscultatory hallmark of this prob-

lem. Aspiration of vomitus may lead to severe pneumonia and

respiratory distress. Respiration is adversely affected by abdom-

inal distention and impaired diaphragmatic excursion.

Closed-loop obstruction is a feared consequence of com-

plete mechanical obstruction. When it occurs, no outlet for

the accumulated intraluminal contents exists, and perforation

of the bowel may occur. Strangulation rarely results from pro-

gressive distention, although venous outflow becomes signif-

icantly impaired as the bowel and mesentery continue to

distend. This ultimately results in intestinal gangrene and

intraluminal bleeding. Free perforation occurs as a conse-

quence of gangrene, releasing the highly toxic stagnant intra-

luminal mixture of bacterial products, live bacteria, necrotic

tissue, and blood. There are no specific historical, physical, or

laboratory findings that exclude the possibility of strangula-

tion in complete small bowel obstruction, which occurs in

approximately one-third of patients. The early appearance of

shock, gross hematemesis, and profound leukocytosis sug-

gests the presence of a strangulated obstruction.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Obstruction of the proximal

small bowel usually presents with vomiting. The extent of

associated abdominal pain is variable and usually is

described as intermittent or colicky with a crescendo-

decrescendo pattern. When the obstruction is located in the

middle or high small bowel (jejunum and proximal ileum),

the pain may be more constant. As the site of involvement

progresses distally, poorly localized crampy pain and abdom-

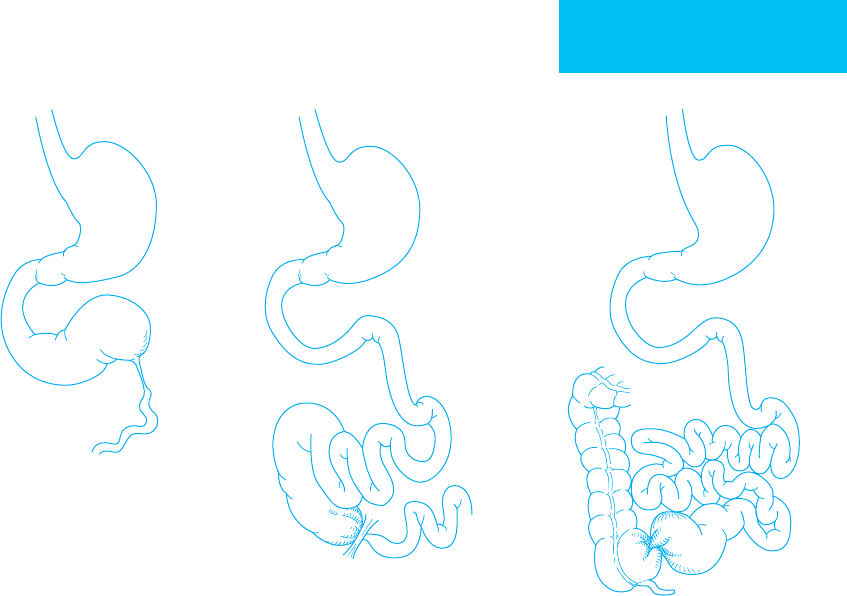

inal distention become more common (Figure 14–1).

In the early stages of obstruction, vital signs are normal.

As loss of fluid and electrolytes continues, dehydration

occurs, manifested as tachycardia and postural hypotension.

Body temperature is usually normal but may be mildly ele-

vated. Abdominal distention is minimal or absent initially. It

is more pronounced with distal obstruction and when more

proximal lesions have been allowed to progress without

decompression. Dilated loops of small bowel may be visible

beneath the abdominal wall in thin patients. Characteristic

peristaltic rushes, gurgles, and high-pitched tinkles may be

audible and occur in synchrony with cramping pain. Rectal

examination is usually normal. Abdominal wall hernias

should be sought.

GASTROINTESTINAL FAILURE IN THE ICU

353

B. Laboratory Findings—Early in the process, laboratory

findings are normal. With progression, there is hemoconcen-

tration, leukocytosis, and electrolyte abnormalities whose

extent and nature depend in part on the level of obstruction

present. Increases in serum amylase are common.

C. Imaging Studies—On plain abdominal films, a ladder-

like pattern of dilated small bowel loops and air-fluid levels

will be noted, particularly in distal obstruction. The colon

may not contain gas. If a gallstone precipitated the event, it

may be noted on the film, or air may be seen in the biliary

tree. When strangulation and necrosis occur, loss of mucosal

regularity, gas within the bowel wall, and “thumbprinting” of

the bowel wall occur. On rare occasions, gas may be seen

within the portal vein. Free air on an upright chest x-ray is

highly suggestive of intestinal perforation.

Contrast studies are usually not required and should not

be performed because of the risk of barium peritonitis if a per-

foration is present. However, in patients with high-grade par-

tial obstructions who are poor surgical risks, administration

of a dilute barium mixture through the nasogastric tube can

be used to determine whether a residual lumen is still pres-

ent for the passage of gas and liquid contents.

Differential Diagnosis

Ileus is a prominent feature of the differential diagnosis. It

can be caused by a number of intraabdominal and retroperi-

toneal processes, including intestinal ischemia, ureteral colic,

pelvic fractures, and back injuries. It may occur after routine

abdominal surgery. If paralytic ileus is present, the pain is

usually not as severe and tends to be more constant.

Obstipation and abdominal distention characterize

obstruction of the large intestine. Vomiting seldom occurs,

and the pain is less colicky. The diagnosis is usually made on

the basis of x-ray findings that show colonic dilation proxi-

mal to the point of obstruction.

Small bowel obstruction can be confused with acute

gastroenteritis, acute appendicitis, and acute pancreati-

tis. Strangulating obstructions may be mimicked by acute

pancreatitis, ischemic enteritis, or mesenteric vascular occlu-

sion owing to venous thrombosis.

High

Frequent vomiting.

No distention. Intermittent

pain but not classic

crescendo type.

Middle

Moderate vomiting.

Moderate distention. Intermittent

pain (crescendo, colicky)

with pain-free intervals.

Low

Vomiting late, feculent.

Marked distention. Variable

pain; may not be classic

crescendo type.

Figure 14–1. Small bowel obstruction. Variable manifestations of obstruction depend on the level of blockage of

the small bowel. (Reproduced, with permission, from Way LW, Doherty GM (eds), Current Surgical Diagnosis & Treatment,

11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002.)

CHAPTER 14

354

Paralytic ileus must be differentiated from mechanical

obstruction. Radiographic findings usually show a more dif-

fuse pattern of air-fluid levels without a distinct cutoff point.

These patients may be very ill with other systemic diseases or

may be apparently well with seemingly minor electrolyte

abnormalities. Pseudo-obstruction is particularly common

among patients with diabetes who are recovering from an

episode of ketoacidosis or who have recently undergone

intraabdominal surgery. Treatment of pseudo-obstruction is

directed at the disease process causing the ileus.

Metoclopramide may be helpful once the presence of

mechanical obstruction has been excluded.

Treatment

A. Supportive Measures—Partial small bowel obstructions

may be treated with intravenous hydration and nasogastric

suction if the patient continues to pass stool and flatus. Fluid

and electrolyte losses are corrected with balanced salt solu-

tions. Isotonic solutions should be used to treat hemocon-

centration. The extent of fluid resuscitation is best guided by

urine output, although in elderly patients or those with car-

diopulmonary disease, a pulmonary artery flotation catheter

is advisable. If strangulation is suspected, broad-spectrum

antibiotics should be administered promptly.

B. Surgery—Planning for surgery should be started concur-

rently with fluid and electrolyte therapy because the patient

must be fully resuscitated before operation commences.

Laparoscopy with lysis of the obstructing adhesion if the

obstruction is due to a simple obstructing band or adhesion

may be all that is required, or open surgery may be necessary

if this cannot be performed laparoscopically. When closed-

loop and strangulated obstructions are present, intestinal

resection may be necessary. The major problem at surgery is

distinguishing viable from necrotic bowel. In severe cases,

patients may have to be returned to the operating room

within 24–48 hours for a “second look” procedure to make

certain that all remaining bowel is viable.

Prognosis

The mortality rate for simple obstruction is almost 2%. It

increases to about 8% if strangulation is present and surgery

is performed within 36 hours of presentation—and to 25% if

operation is delayed beyond that point.

Cheadle WG, Garr EE, Richardson JD: The importance of early

diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Am Surg 1988;54:565–9.

[PMID: 3415100]

Frazee RC et al: Volvulus of the small intestine. Ann Surg

1988;208:565–8. [PMID: 3190283]

Pain JA, Collier DS, Hanka R: Small bowel obstruction: Computer-

assisted prediction of strangulation at presentation. Br J Surg

1987;74:981–3. [PMID: 3319029]

Pickleman J, Lee RM: The management of patients with suspected

early postoperative small bowel obstruction. Ann Surg

1989;210:216–9. [PMID: 2757422]

Obstruction of the Large Bowel

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Constipation or obstipation.

Abdominal distention and tenderness.

Abdominal pain.

Nausea and vomiting (late).

Characteristic x-ray findings.

General Considerations

About 15% of intestinal obstructions involve the large bowel.

The sigmoid colon is most commonly involved. When com-

plete obstruction is present, carcinoma usually is the cause.

Other causes include diverticular disease, volvulus, inflam-

matory disorders, benign tumors, and fecal impaction.

Obstructive bands from adhesions and intussusception are

rare causes of large bowel obstruction.

If obstruction occurs at the level of the cecum, the signs

and symptoms will be similar to those of small bowel

obstruction. With more distal colonic obstruction, physical

findings will depend on the competence of the ileocecal

valve. A form of closed-loop obstruction will occur if the

colon cannot decompress itself in retrograde fashion

through the ileocecal valve into the small bowel.

Colonic distention is a progressive process in which intra-

luminal pressures can reach very high levels that can impair

the circulation and lead to gangrene and perforation.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients typically complain of a

deep-seated cramping pain referred to the hypogastrium.

Lesions of fixed portions of the colon (ie, cecum, hepatic

flexure, and splenic flexure) radiate anteriorly. Pain from

obstruction of the sigmoid colon usually radiates to the left

lower quadrant. Severe continuous pain suggests intestinal

ischemia. When a progressive process is responsible, the

obstruction may develop insidiously, although careful ques-

tioning often reveals signs of chronic disease such as a

change in stool caliber, frequency of defecation, and dark or

black feces.

The usual feature of complete obstruction is constipation

or obstipation. Vomiting is a late finding and may not occur if

the ileocecal valve does not allow contents to reflux back into

the small intestine. Feculent vomiting is a late manifestation.

Abdominal distention with peristaltic waves radiating

across the abdominal wall may be observed if the patient is

thin. On auscultation, high-pitched metallic tinkling and

associated rushes and gurgles can be heard. Localized tender-

ness or a nontender palpable mass may indicate a strangu-

lated closed loop. Occult blood on rectal examination may be

GASTROINTESTINAL FAILURE IN THE ICU

355

due to carcinoma, whereas fresh blood is characteristic of

diverticular disease and intussusception.

B. Endoscopy—Sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are often

beneficial in establishing the diagnosis and may be therapeu-

tic if sigmoid volvulus is present. Care must be exercised

when advancing the endoscope to prevent accidental perfo-

ration of an attenuated colonic wall.

In strictures, dilatation and stenting can be therapeutic or

allow bowel preparation before definitive surgery, making a

diverting colostomy unnecessary. Fulgeration of inoperable

obstructing carcinomas can restore a lumen to palliate an

inoperable lesion.

C. Imaging Studies—Plain abdominal x-rays reveal a dis-

tended colonic segment. With low sigmoid or rectal obstruc-

tions, the entire colon may be dilated. If the ileocecal valve is

incompetent, retrograde decompression will cause distention

of the terminal ileum.

The diagnosis is confirmed by barium enema. Water-

soluble contrast medium should be used if strangulation or

perforation is suspected. Barium is contraindicated in the

presence of suspected colonic perforation.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to differentiate small bowel obstruction

from colonic obstruction. With the latter, onset is typically

slower, and there is less pain. Vomiting is very unusual with

colonic obstruction despite considerable abdominal dis-

tention. Plain abdominal x-rays are essential to the differ-

ential diagnosis, and adjunctive contrast studies are

sometimes helpful.

Treatment

The primary goal of therapy is decompression of the

obstructed segment and prevention of perforation.

Operation is almost always required in cases of mechanical

obstruction. The surgical procedure depends on the lesion

present, the status of the patient, the extent of colonic dila-

tion, and whether there is evidence of perforation. In general,

proximal diversion (colostomy) is required to decompress

the dilated colon. Simultaneous or subsequent excision of

the obstructing lesion is required before colonic continuity

can be reestablished.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the age and general condition of

the patient, as well as on the extent of vascular impairment

of the bowel, the presence or absence of perforation, the

cause of obstruction, and the promptness of surgical man-

agement. Mortality rates are about 20% overall. If the cecum

perforates, a mortality rate of 40% can be expected. In the

case of colonic obstruction secondary to carcinoma, the

prognosis is worse.

Buechter KJ et al: Surgical management of the acutely obstructed

colon: A review of 127 cases. Am J Surg 1988;156:163–8.

[PMID: 3048132]

Gosche JR, Sharpe JN, Larson GM: Colonoscopic decompression

for pseudo-obstruction of the colon. Am Surg 1989;55:111–5.

[PMID: 2916799]

Harig JM et al: Treatment of acute nontoxic megacolon during

colonoscopy: Tube placement versus simple decompression.

Gastrointest Endosc 1988;34:23–7. [PMID: 3350299]

Sloyer AF et al: Ogilvie’s syndrome: Successful management with-

out colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci 1988;33:1391–6. [PMID: 3180976]

Adynamic (Paralytic) Ileus

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Continuous abdominal pain.

Vomiting.

Abdominal distention.

Obstipation.

Precipitating factor.

Radiographic evidence of gas and fluid in the small or

large bowel.

General Considerations

Adynamic ileus is often associated with neurogenic or mus-

cular impairment of small or large bowel function. This may

be due to a variety of causes such as alimentary tract surgery,

a ruptured viscus, hemorrhage, pancreatitis, or peritonitis.

Other causes include anoxic injury, anticholinergic medica-

tions, opioids, vertebral fractures, renal colic, injuries of the

spinal cord, severe infections of either the thoracic or the

abdominal cavity, uremia, diabetic coma, and electrolyte

abnormalities.

Recent abdominal surgery is a principal cause of ady-

namic ileus among critical care patients. In the 24 hours fol-

lowing surgery, motility within the small bowel returns to

normal, whereas gastric function will return after approxi-

mately 24 hours. The colon requires several days to regain

normal motility. The pain associated with ileus is constant

but not severe or colicky, as it is with mechanical obstruction.

Mild abdominal tenderness is noted along with distention. If

this is due to an intraperitoneal inflammatory process, signs

and symptoms of that disorder are usually present. Plain

films of the abdomen are extremely helpful.

Similar to paralytic ileus of the small bowel, pseudo-

obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) of the colon may occur.

This is a severe form of ileus that often arises in bedridden

patients who have serious systemic illnesses. The abdomen is

usually silent, and abdominal cramping is not present.

Tenderness may be noted. Plain films show a dilated colon

that may reach alarming proportions. The entire colon may

CHAPTER 14

356

contain gas, but the distention is typically localized to the

right colon with cutoff at the splenic flexure. Contrast stud-

ies may be required to prove the absence of obstruction, but

instillation of radiopaque material must be stopped as soon

as the dilated colon is reached. The risk of cecal perforation

is very high in patients with pseudo-obstruction.

Decompression of the colon should be attempted as quickly

as possible using a fiberoptic colonoscope. Recurrence rates

are as high as 20%. Initial colonoscopic decompression is

successful in 90% of patients. Percutaneous cecostomy is

reserved as an option for decompression if colonoscopy fails.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Mild to moderate abdominal

pain is usually present. It is continuous rather than colicky

and is often associated with emesis, which may become fecu-

lent. Symptoms of the underlying condition also may be

present, such as prostration from a ruptured viscus.

Dehydration is usually present as a consequence of fluid

translocation into distended loops of bowel. Massive abdom-

inal distention and localized tenderness are common. Bowel

sounds are absent or decreased.

B. Laboratory Findings—Hemoconcentration and elec-

trolyte deficits occur with prolonged vomiting. Elevated

serum amylase levels and leukocytosis are usually present.

C. Imaging Studies—The specific radiographic finding

noted on flat-plate upright abdominal films is gas-filled

loops of intestine. Air even may be present in the rectum.

Air-fluid levels in the distended bowel are common. A con-

trast enema or barium swallow with subsequent small bowel

“follow through” films may be helpful in differentiating ady-

namic ileus from mechanical obstruction.

Differential Diagnosis

Idiopathic pseudo-obstruction is usually seen in teenagers or

young adults and is characterized by symptoms of small

bowel obstruction that recur but never produce evidence of

organic obstruction on x-ray. Treatment is with nasogastric

intubation and suction. Intravenous fluids and parenteral

nutrition are required. Occasionally, colonoscopic decom-

pression or cecostomy is useful. The variant known as chronic

pseudo-obstruction is associated with cramping abdominal

pain, abdominal distention, and vomiting. There may be

involvement of the esophagus, the stomach, the small bowel,

the colon, or the urinary bladder. All or some of these

patients have abnormal motility with sparing of some por-

tions of the alimentary tract. Metoclopramide is often help-

ful. Avoiding narcotic analgesics may prevent an ileus. Use of

thoracic epidural analgesia and postoperative local anes-

thetic wound devices will reduce the need for narcotics.

Treatment

A. Supportive Measures—Most cases of ileus in the post-

operative period respond to restriction of oral intake and

nasogastric suction. Fluid and electrolyte replacement is

essential.

B. Decompression—When colonic dilation is present,

colonoscopy may be valuable. Use of a rectal tube was com-

mon practice at one time but now has been largely abandoned.

C. Surgery—If there is a failure of conservative therapy, sur-

gery may be necessary. Operation is performed to decom-

press the bowel either by enterostomy or by cecostomy and to

exclude mechanical obstruction. Bowel biopsy may be per-

formed to identify neurogenic causes.

Prognosis

The initiating disorder often will dictate the prognosis.

Adynamic ileus may resolve without specific therapy.

Decompression usually helps to return bowel function to

normal.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Recent studies have reported the use of new agents in the

treatment of adynamic ileus. Itopride has shown some effect

in postoperative ileus. Cisapride has been discontinued

owing to side effects. Erythromycin was studied and showed

no advantage when compared with placebo. Intravenous

lidocaine also has been found to shorten the duration of par-

alytic ileus, presumably by suppressing inhibitory GI reflexes.

Additional trials of all these agents are required before they

can be either recommended or discredited.

Bonacini M et al: Effect of intravenous erythromycin on postoper-

ative ileus. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:208–11. [PMID:

8424422]

Dorudi S, Berry AR, Kettlewell MG: Acute colonic pseudo-

obstruction. Br J Surg 1992;79:99–103. [PMID: 1555081]

Gurlich R, Frasco R, Maruna P, Chachkhiani I. Randomized clini-

cal trial of itopride for the treatment of postoperative ileus after

laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Chir Gastroenterol 2004;20:

61–65.

Jetmore AB et al: Ogilvie’s syndrome: Colonoscopic decompres-

sion and analysis of predisposing factors. Dis Colon Rectum

1992;35:1135–42. [PMID: 1473414]

MacColl C et al: Treatment of acute colonic pseudoobstruction

(Ogilvie’s syndrome) with cisapride. Gastroenterology

1990;98:773–6.

Rimback G, Cassuto J, Tollesson PO: Treatment of postoperative

paralytic ileus by intravenous lidocaine infusion. Anesth Analg

1990;70:414–9. [PMID: 2316883]

Vantrappen G: Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Lancet

1993;341:152–3. [PMID: 8093750]

DIARRHEA & MALABSORPTION

Critically ill patients often develop diarrhea from a number of

causes, including overly aggressive enteral feeding, infectious

diarrhea, and malabsorption. After GI resection, short gut

syndromes and exocrine insufficiency may contribute. These

common causes are discussed in the next several sections.