Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

INTRODUCTION

■

Most standard prehistories of Europe end with the

Roman conquest of central and western Europe in

the last two centuries

B.C. and the first century A.D.

We have decided to extend our coverage of prehis-

toric and early historic Europe to approximately

A.D. 1000 for several reasons. First, the Romans

conquered only a part of temperate Europe. While

the Romans controlled southern Britain, Gaul, Ibe-

ria, the Mediterranean, and parts of east-central Eu-

rope, Roman political and military domination

never extended to Ireland, Scandinavia, Free Ger-

many (those areas of Germany outside the borders

of the Roman Empire), and all of northeastern

Europe. Regions such as Ireland and the por-

tions of Germany that bordered the Roman Empire

certainly were affected directly by Roman trade,

religion, and military activities. However, there

were substantial continuities between the

Early (or pre-Roman) Iron Age and the Roman

Iron Age in many regions of northern and eastern

Europe.

Second, the Roman political, military, and eco-

nomic domination of many parts of western Europe

lasted for only about four hundred years. Archaeo-

logically, Britain is the most studied of all the

Roman provinces in western Europe. Major pro-

grams of excavation in York, Winchester, and Lon-

don have shown that Roman towns and cities expe-

rienced severe depopulation in the fifth century

A.D.

and that large-scale production of commercial

goods such as pottery had ceased by about the year

400. The Roman military withdrew from the prov-

ince of Britain in the early fifth century, and the resi-

dents were forced to see to their own defenses. Sim-

ilar patterns of political, urban, and industrial

decline have been documented throughout the

Western Roman Empire in the fifth century. Long

before the final Western Roman emperor was de-

posed in

A.D. 476, many of the hallmarks of Roman

civilization—military control over a well-defined

territory, urbanism, industrial production and ex-

change, coinage, and literacy—had effectively disap-

peared in many of the western provinces.

Third, by the sixth century

A.D., a series of small

successor kingdoms had been established within the

boundaries of the former Western Roman Empire.

These new rulers modeled themselves on the former

Roman emperors. Many, including the Frankish

King Clovis, adopted Christianity, and some had

served as mercenaries in the Roman army. Howev-

er, the rulers themselves were drawn from barbarian

tribes whose homelands lay outside the boundaries

of the former Roman Empire. Moreover, the poli-

ties they ruled—Merovingian France, Anglo-Saxon

England, Visigothic Spain—were substantially dif-

ferent from the Roman provinces that had existed

in these regions a century or two earlier. These Dark

Age societies were rural rather than urban. They

have much more in common with the barbarian so-

cieties of Iron Age Europe than with the Roman so-

cieties that immediately preceded them. Since liter-

ary evidence and written records are limited, nearly

all our information about daily life in these succes-

sor kingdoms has been discovered through archaeo-

logical research.

ANCIENT EUROPE

321

CHRONOLOGY

This volume covers only a portion of the European

Middle Ages. Traditionally, the medieval period be-

gins with the collapse of the Western Roman Em-

pire in the fifth century

A.D. and ends with the Euro-

pean voyages of discovery in the fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries. While we begin our coverage of

the Early Middle Ages in the early fifth century, we

have chosen to end our coverage of medieval ar-

chaeology at about

A.D. 1000. Archaeological and

historical records provide clear evidence for the for-

mation of states in Scandinavia and Poland around

this time. With the establishment of institutional-

ized governments organized on territorial princi-

ples, many of the societies of northern Europe no

longer can be considered barbarian. In addition, at

about this time Christianity was adopted and litera-

cy became widespread in several regions of north-

eastern Europe, including Poland and Scandinavia.

As a result, written records are far more common.

The archaeology of the High Middle Ages (c.

A.D.

1000–1500) is truly a form of historical archaeolo-

gy, where documents and material evidence have

equally important roles to play.

MIGRATION

Migration or population movement is a well-

documented feature of ancient Europe. At the end

of the Ice Age (eleven thousand years ago), hunters

and gatherers moved into areas of Europe that had

been glaciated during the Pleistocene. Both archae-

ological and skeletal evidence indicates that migra-

tion played a role in the establishment of the first

farming communities in central Europe. Archaeo-

logical, place-name, and literary evidence shows

substantial population movements in central Eu-

rope during the later Iron Age.

Population movements are also well document-

ed throughout the Early Middle Ages, and the peri-

od from

A.D. 400–600 often is referred to as the Mi-

gration period. In the fifth and sixth centuries

A.D.,

barbarians from outside the Roman Empire—

Visigoths, Angles, Saxons, Franks, and others—

moved into many regions of western Europe. The

nature of these migrations has been debated by

both archaeologists and historians for decades. Do

they represent large-scale population movements,

or are they small migrations of a military and politi-

cal elite who dominated the local sub-Roman (early

post-Roman, non-Saxon) populations and initiated

changes in material culture and ideology? Today,

many archaeologists would favor the latter explana-

tion. This chapter profiles many of the Migration

period peoples who are known to us through the ar-

chaeological record and through historical sources.

Perhaps the best known of the early medieval

migrations is the Viking expansion (c.

A.D. 750–

1050). Eastern Vikings from Sweden established

colonies in Russia and the Baltic and conducted

trade in distant eastern lands such as Mesopotamia.

Western Vikings, from Norway and Denmark, es-

tablished colonies in Britain, Ireland, Orkney, and

Shetland. In addition, Viking colonists settled Ice-

land in the ninth century and Greenland in about

985. These settlements represent the frontiers of

European colonization in the Early Middle Ages.

Archaeologists have made extensive studies of the

colonial settlements established by both the eastern

and western Vikings.

THE REBIRTH OF TOWNS

AND TRADE

In A.D. 600 Europe was primarily a rural society. Al-

though many former Roman towns continued to

serve as political and ecclesiastical centers, their pop-

ulations were substantially reduced, and the towns

no longer served as major centers of manufacturing

and trade. Recent archaeological research in the

Mediterranean regions of Europe and North Africa

indicates that long-distance trade had declined well

before the Islamic conquests of North Africa and

Spain in the seventh century

A.D.

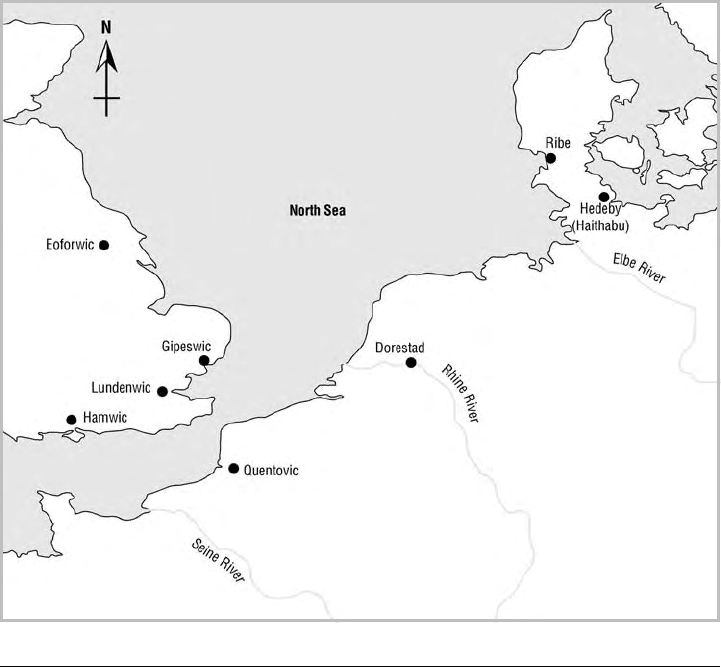

Beginning in the seventh century

A.D. a number

of emporia—centers of both long-distance and re-

gional trade—were established along the North Sea

and Baltic Coasts from Hamwic (Anglo-Saxon

Southampton) in England to Staraya Ladoga in

Russia. Major programs of archaeological research

have been carried out at these emporia. For exam-

ple, the Origins of Ipswich project traced the devel-

opment of this emporium from its establishment in

the early seventh century. Ipswich produced pot-

tery, known as Ipswich ware, that was formed on a

slow wheel and kiln-fired. This pottery was traded

throughout East Anglia, and it also appears at royal

and ecclesiastical centers in other parts of England.

The trade networks that were established in the

Early Middle Ages are entirely different from those

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

322

ANCIENT EUROPE

that existed during the Roman period. Many

Roman trade networks centered on the Mediterra-

nean; early Medieval networks centered on the Bal-

tic and North Sea. Some archaeologists have argued

that the establishment of these emporia may be

closely related to state formation and the emergence

of complex societies in several regions of northern

Europe, including England, France, and Scandina-

via.

CONCLUSION

Between A.D. 400 and 1000, the European conti-

nent was transformed politically, socially, and eco-

nomically. The breakup of the Western Roman Em-

pire created a power vacuum that was filled by a

series of barbarian successor kingdoms. In a period

of only six centuries urbanism was established in Eu-

rope, both within and outside the former Roman

Empire; new patterns of long-distance and regional

trade developed centering on the Baltic and the

North Sea; and states formed in many regions of

Europe. These transformations laid the foundation

for the later medieval and modern European

worlds.

PAM J. CRABTREE

INTRODUCTION

ANCIENT EUROPE

323

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

EMPORIA

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAYS ON:

Ipswich . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 331

Viking Harbors and Trading Sites . . . . . . 334

■

The use of the term “emporia” to refer to the spe-

cialized trading (and crafting) sites of the late sev-

enth century to the ninth century owes much to

Richard Hodges and especially his Dark Age Eco-

nomics (1982). Influenced by anthropologists and

economic historians, Hodges saw these emporia as

centers created on the frontiers of early medieval

kingdoms (but largely divorced from their sur-

rounding hinterland) through which kings funneled

and controlled long-distance trade in prestige

goods. However, it is important to be aware that

contemporaries would not have applied the term

“emporium” to all the sites Hodges considers.

Eighth- and ninth-century sources do refer to Lun-

denwic (London, England), Dorestad (Holland),

and Quentovic (France) as “emporia,” but Hamwic

(the best-studied and most-famous of Hodges’s

emporia) is only ever referred to as a mercimonium.

Deriving from merx, the Latin for goods, merchan-

dise, or wares, this term also relates to trade and ex-

change but presumably on a different scale or in dif-

ferent goods. As scholars have come to appreciate

the comparative rarity of “emporia” in early medi-

eval Europe, so they have gradually come to use the

Old English word wic to refer to the whole class of

such settlements. Contemporaries were more dis-

criminating.

LAYOUT

Hodges used the presence (or absence) of particular

classes of archaeological evidence to divide his “em-

poria” into three types. Type A emporia were char-

acterized by the presence of exotic material culture

and an absence of evidence for permanent struc-

tures. Sites such as Dalkey Island (Ireland) were

thought to resemble the seasonal fairs referred to in,

for example, the Icelandic sagas. However, like

other archaeologists, he has devoted most of his at-

tention to so-called type B emporia.

These were permanent, strategically located,

and in early medieval terms, substantial settlements.

Dorestad (Holland) ran for about 3,000 meters

along the old course of the Kromme Rijn at the

point where it intersected with the Lower Rhine,

and the Lek Ribe (Denmark) was situated where a

north-south route crossed a ford in the River Ribe,

the latter itself connecting the settlement to the

North Sea. Similarly Eoforwic (York, England) lay

at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss, close

to a natural crossing point of the Ouse and on the

line of a Roman road. Hamwic (Southampton, En-

gland) covered some 45 hectares of the west bank

of the River Itchen, at the point where it flowed into

Southampton Water and ultimately the English

Channel.

324

ANCIENT EUROPE

Main emporia (wics) of northwest Europe.

Hamwic may have had a population of between

2,000 and 3,000 and, like many other emporia or

wics, seems to have been planned. Two north-south

roads, connected by a series running east-west,

formed a gridlike pattern within a defining (not de-

fensive) enclosure. The roads were lined with build-

ings, and although these did not differ much from

those found on contemporary rural sites, a visitor

might have been impressed by the number concen-

trated in one place. Dorestad is characterized by a

series of landing piers (about 8 meters wide)

stretching into what would have been the River

Rhine. They appear to have been lengthened as the

river shifted to the east and were major structuring

elements in the layout of the settlement—it was di-

vided into 20-meter-wide parcels, each containing

two piers, which ran from the riverside, through the

harbor area, and into the vicus (trading zone) to the

west. At Ribe a series of parallel ditches divided the

settlement into forty or fifty plots, but here the evi-

dence for permanent buildings is less secure. Most

archaeologists argue that planning implies the in-

volvement of a central authority (usually the king)

in the establishment and running of the emporia;

for example, King Ine of Wessex (688–726) at

Hamwic and King Angantyr at Ribe. These (and

other emporia) have therefore been seen primarily

as royal settlements.

IMPORTS

Type B emporia are also characterized by the pres-

ence of significant quantities of exotic material cul-

ture. A cowrie shell (from the Red Sea or the Indian

Ocean) and the hypoplastron (shell fragment) of a

North African green turtle from Hamwic, a bronze

statuette of Buddha from eighth-century contexts at

Helgö (Sweden), and pieces of carnelian, garnets,

and rock crystal at Ribe illumine connections with

points far to the south and east (fig. 1). The sharp-

ening stones, soapstone vessels, and whalebone

from Ribe, on the other hand, are indicative of con-

nections with the North. They also stand for the

furs that flowed from the northern lands, through

emporia like Ribe and Birka (Sweden), to satisfy

EMPORIA

ANCIENT EUROPE

325

elite demand in the heartlands of Europe. The bone

assemblage from Birka reveals that skins of moun-

tain hare, squirrel, beaver, fox, ermine, pine marten,

badger, wolverine, and otter were processed at the

emporium. At Eoforwic there is similar evidence for

the working of beaver and pine marten skins. The

value of these furs should not be underestimated. In

the ninth century a Norwegian merchant called

Óttar grew wealthy on the tribute he exacted from

the Saami, and that tribute included the skins of

marten, reindeer, otter, bear, and seal. A large ring-

headed pin and part of a fitting for an Irish brooch

provide evidence for Hamwic’s hitherto neglected

westerly connections, while Pictish brooches pro-

vide the closest parallels for a gilded, penannular

brooch terminal from Eoforwic.

The bulk of the evidence for imports from the

major wics, however, consists of pottery, mostly

from sources in the Rhineland and in northern

France and the Low Countries. Kilns discovered

near Rouen produced much of the material import-

ed (perhaps via the French site of Quentovic) into

Hamwic, although there was also some pottery

from Belgium or Holland (or both) as well as Ba-

dorf and Mayen wares from the Rhineland. Similarly

black and gray burnished wares from northern

France or the Low Countries (or both) dominate

the imported assemblages from Eoforwic and Lun-

denwic.

By contrast, the imported pottery from

Gipeswic (Ipswich, England) is dominated by the

products of the Vorgebirge and Mayen kilns in the

Rhineland and thus more closely resembles the as-

semblages from Ribe and Dorestad. Much of the

other “exotic” material culture on these sites can be

sourced to the Rhineland—for example, glass ves-

sels, lava quern stones (for grinding grain), and wine

barrels (reused to line wells at Dorestad and Ribe).

This mention of wine should serve as a reminder

that the merchants (and consumers) of early medi-

eval Northwest Europe were probably more inter-

ested in the contents than in the vessels (both

wooden and ceramic). Analysis of one sherd from

Hamwic revealed that the vessel had contained a

mixture of meat and olive oil, showing that wine

was not the only exotic consumable traded across

northwestern Europe.

Although Rhenish quern stones and glass ves-

sels are also found at, for example, Eoforwic and

Hamwic, an analysis of the distribution of imported

pottery encouraged Hodges to propose the exis-

tence of mutually exclusive trading zones—a Rhe-

nish one in the north (including Dorestad,

Gipeswic, and Ribe), and a Frankish one in the

south (including Hamwic, Quentovic, and now

Lundenwic). He believed that the wics or emporia

were the linchpins of both networks and that they

were consciously established by kings in an attempt

to exert greater control over an expansion of pres-

tige goods exchange that threatened their posi-

tion—if they did not control this trade (and the

traders), it is argued, then their social inferiors

would have had access to the symbols of power.

Their position as chief “ring givers,” as the sole arbi-

ters of the social hierarchy, would have been under-

mined. A letter written by Charlemagne, the Caro-

lingian emperor, to Offa, king of Mercia, in 796

reveals some fascinating insights into the nature of

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

326

ANCIENT EUROPE

this exchange as well as new perspectives on the ob-

jects involved.

In this letter Charlemagne refers to Offa’s earli-

er request for some “black stones” of a certain

“length” and tells him to send a messenger with de-

tails of “what kind you have in mind and we will

willingly order them to be given, wherever they are

to be found, and will help with their transport.”

Charlemagne then informs Offa about his require-

ment for cloaks of a certain size and asked that they

“be such as used to come to us in former times.”

This all reads like a record of one moment in a well-

established, routine, and regular system of ex-

change. The fact that Charlemagne and Offa got in-

volved in discussions about the exchange of items

as (apparently) mundane as “cloaks,” and the gener-

ally accepted argument that the “black stones” were

tephrite quern stones from sources in the Eifel

mountains (near Mayen in the Rhineland), rein-

forces the argument that long-distance exchange in

the eighth and ninth centuries was directed and

controlled by kings (and emperors).

Research since the 1980s, however, while con-

firming royal interest in long-distance trade, has

somewhat modified the impression that this in-

volvement extended beyond prestige goods to utili-

tarian objects. Thus David Peacock has presented a

convincing case that Charlemagne’s black stones,

rather than being humble lava querns, were in fact

antique black porphyry columns from Rome and

Ravenna. As such they were laden with the symbol-

ism of empire and antiquity; they were objects of

immense political and social value—the “stuff of

emperors.” In this light it also seems inherently un-

likely that the “cloaks” were simple, utilitarian

items. They, too, were probably luxury products—

perhaps like the late-eighth-century or ninth-

century Anglo-Saxon embroideries preserved at

Maaseik (Belgium).

Clearly the exchange of prestige gifts did play a

significant part in the political strategies of early me-

dieval kings and emperors. However, it now seems

that they did not necessarily involve themselves in

the trading of quern stones—although the archaeo-

logical evidence for them on sites across northwest-

ern Europe is proof that such trading did take place.

The question of the “controlling hand” behind that

trade, if not always that of the king, is one to which

this discussion will return. However, at this point it

should be emphasized that the wics were essentially

transhipment points. They were places where goods

from afar entered the country before, according to

the Hodges model, being forwarded to the king for

redistribution. One would not expect to find large

quantities of prestige goods at these sites—and this

is, by and large, the case. The textual references to

columns, embroideries (if that is what they are), and

slaves (see the Venerable Bede’s reference in Ecclesi-

astical History of the English People book 4, chapter

22, to the sale, at Lundenwic, of a Northumbrian

slave to a Frisian merchant) thus provide useful il-

lustrations of the kind of trade items that might

have passed through the emporia.

PRODUCTION

In his original formulation of the characteristics of

type B emporia (in Dark Age Economics), Hodges

argued that they would have housed a native work

force whose role was to produce for “the mercantile

community.” The “subsidiary” role attributed to

these artisans was a product both of the limited

amount of evidence (in 1982) for craft production

on the wics and of the attention devoted to overseas

exotica. The idea that these sites were primarily con-

cerned with facilitating the exchange of exotica be-

tween elites reinforced the impression that they

were largely divorced from the region within which

they were situated.

However, as excavation and publication pro-

gressed in the years since 1982, and the evidence for

craft production on the wics accumulated, so it has

become clear that scholars have underestimated the

significance of production in the Anglo-Saxon

economy in general—and on the wics in particular.

Hamwic (as in so many other respects) provides the

best evidence for the range and scale of artisanal ac-

tivity; this can be used as the framework for a more

general consideration of craft production in the

main Northwest European emporia. Since 1982

new insights have accumulated into the role of em-

poria and wics in the regional economies of the

Early Middle Ages.

At Hamwic, as elsewhere (good evidence comes

from Ribe), artisanal activities were carried out in

and around the buildings that lined the roads, and

all forms of craft working were carried out right

across the site, with no clear sign of the zoning of

particular “industries.” The scale of production

EMPORIA

ANCIENT EUROPE

327

within each of the properties differed little from that

on contemporary rural settlements, but the possibil-

ities offered by the coexistence in close proximity of

many different kinds of craft production probably

more than offset this “limitation.”

One of the most ubiquitous traces of craft pro-

duction at Hamwic is the debris from ironworking.

This usually takes the form of smithing slag found

in association with ore, charcoal, furnaces, and raw

iron (the same is true at Gipeswic, Lundenwic, and

Eoforwic). As at Dorestad, iron was smelted else-

where (perhaps at Romsey, 14 kilometers to the

northeast) and was transported to Hamwic for the

production of a wide variety of objects, including

chisels, axes, shears, nails, rivets, needles, keys, bells,

and knives (at Eoforwic evidence exists for the plat-

ing of some of these objects with tin, tin-lead, and

copper). The iron ingots worked at Dorestad proba-

bly originated on production sites in the Veluwe re-

gion, about 40 kilometers to the northeast. By and

large the objects made were similar to those pro-

duced at Hamwic, but Frankish swords with inlaid

blades (among the most prestigious artifacts of the

period) might also have been made here.

The working of copper alloys was the most

prevalent of the nonferrous metallurgical crafts on

all the Northwest European wics. Crucibles, cupels,

and molds provide the bulk of the evidence for the

production of what seem, for the most part, to have

been rather mundane objects—for instance, pins,

strap ends, buckle fittings, finger rings, and brooch-

es. There is, however, evidence (usually in the form

of molds) for the production of some more decora-

tive (quality) items at Hamwic and Gipeswic; a bone

mold for the production of a disk brooch was found

at Lundenwic. The bronze workers at Ribe seem to

have made jewelry of distinctively Scandinavian

type, as if catering for the regional as opposed to the

“long-distance” market. Given the rather mundane

quality of many of the objects produced on this and

other wics, one can probably argue that most pro-

duction of these sites was destined for regional level

exchange. This has significant implications for how

scholars understand the emporia (see below).

Precious metals were worked on the wics. Gold

and silver were present in cupels and crucibles from

Hamwic, and some evidence exists for gilding. Sil-

ver objects are rare (as this would have been trans-

shipment site), but they do seem to have been pro-

duced from the earliest phase of the settlement.

Fragments of gold and silver wire and plate from the

excavations at Fishergate in York demonstrate that

“prestige” objects were being made at Eoforwic, as

does an emerald and two fragments of garnet. It

seems certain that sceattas (small eighth-century sil-

ver coins) were minted at Ribe, Gipeswic, and Ham-

wic. Glass was worked (rather than made) at Eofor-

wic, Ribe, and Dorestad, while the latter two have

evidence for the production of amber objects.

Despite the fact that, in most cases, little direct

evidence exists for the production of pottery at wics

(see below for the exception), there can be little

doubt that it should be added to the range of crafts

practiced on them. No kilns have been found at

Hamwic, but here, as elsewhere, the vast majority

of the pottery was produced from local clays, and

small, ephemeral kilns would have sufficed to make

it. The facts that some of the Hamwic pottery de-

rived from sources about 20 kilometers away and

that the sand- and shell-tempered wares from Eo-

forwic belonged to widespread ceramic traditions

suggest that the wics were integrated into regional

systems of production and distribution. The pro-

duction and distribution of Ipswich ware leads to

the same conclusion.

Fired in kilns and produced on a slow wheel,

Ipswich ware was (mass-)produced in the northeast-

ern part of Gipeswic from the early part of the

eighth century. Not only did its manufacture repre-

sent a technological advance on any other kind of

ceramic production then taking place in England, it

was also made in a wider range of forms and

achieved a much wider distribution. It is almost

ubiquitous on settlements within the kingdom of

East Anglia, suggesting that it was made and traded

within a regional system focused on the wic. Out-

side the kingdom of the East Angles (it is found as

far north as York and as far south as Kent), it is nor-

mally found on elite sites and usually in the form of

storage vessels. Although, again, the contents may

have been more valuable than the vessel, the pro-

duction and distribution of the latter does suggest

that traditional models may have underestimated

the significance of trade within and across the king-

doms of England and the role of the wics in articu-

lating this “economic” activity. A consideration of

the bone objects from the emporia leads to the same

conclusion.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

328

ANCIENT EUROPE

At Hamwic cattle bone was the preferred mate-

rial for the production of combs, spindle whorls,

needles, awls, and thread pickers (red deer antler

was increasingly used in the ninth century). Al-

though there are some variations (the production of

playing counters, amulets, and skates at Dorestad;

the latter were also made at Eoforwic), the bone

workers on the other wics seem to have made a very

similar range of products. This implies, again, that

production was designed for local or regional con-

sumption—why export a (rather utilitarian) product

to a community that also manufactures it? (Combs

produced in Hamwic have now been identified in its

hinterland—at Abbots Worthy, near Winchester.)

The similarity in products created at various wics

also points to one of the “benefits” of the concen-

tration of different kinds of artisanal activity. There

are some signs of the emergence of an integrated

system of production in that many of the bone (and

other) tools manufactured there were used in other

productive processes.

Textile production would seem to have been

one of the most important of these. Weaving pits

have been identified in the Six Dials area of Ham-

wic, while more than five hundred loom weights

were found on the site of an extension to the Royal

Opera House in Lundenwic. Loom weights were

also found at Dorestad, while one of the products

of this craft (a fragment of a coarse wool textile) was

recovered from an early-eighth-century context at

Eoforwic. There is evidence for leatherworking at

Hamwic and Gipeswic, and shoes were made on the

East Anglian wic. As already noted, furs were pro-

cessed at Eoforwic and Birka. In fact these animal

“secondary products” provide crucial insight into

the function (and rationale) of the emporia; the

products were made with tools and materials deriv-

ing from animals that were supplied from the sur-

rounding region to the craft workers in the wic.

These artisans then created objects of varying value.

Certain of these, such as the furs and some of the

textiles and bone work (an early-eighth-century

bone knife handle from Eoforwic was beautifully

decorated with scenes of animals in procession) as

well as the objects of gold and silver, might have

been destined for the elite consumption, prestige

goods exchange, or both; the rest (and probably the

majority) would have been consumed at the region-

al level.

RATIONALE AND DEMISE

Classic accounts of the emporia saw them as royally

controlled foreign enclaves, situated within, yet sep-

arate from, the various kingdoms of northwestern

Europe. They were seen as nodes in a pan-European

exchange system, operated by elites for the benefit

of elites—the driving forces of early European histo-

ry. Some of the gifts exchanged between the kings

of northwestern Europe may have passed through

the wics; some may even have been made there.

However, if the character of the archaeological as-

semblage in any way reflects the importance of past

human activities, it is now clear that artisanal pro-

duction dominated the lives of most of the residents

of early medieval emporia. This production con-

nected them, on a daily basis, with the inhabitants

of the surrounding region. It seems likely that the

latter “consumed” many of the goods made on the

wics, although (given the generic nature of these

products) this will remain difficult to prove. What

is unquestionable, however, is that the artisans (and

possibly traders) on the wic were provisioned, both

in terms of food and raw materials, with resources

produced in its hinterland.

The remains of rather elderly cattle, sheep, and

pigs dominate the faunal assemblage from Hamwic.

These animals had evidently served a useful life else-

where before being dispatched to the wic. The as-

semblage is noteworthy for the absence of young

animals, which would have supplied the better cuts

of meat, and for a lack of wild species. It appears that

the inhabitants of Hamwic were not able to exercise

much choice over the food with which they were

supplied, and this is generally taken to support the

idea that the wic was created, controlled, and provi-

sioned by the king from his other estates in the

kingdom of Wessex.

The evidence from other emporia, however,

suggests that Hamwic might, to some extent, be ex-

ceptional. There is evidence for farms on the edge

of Dorestad and Lundenwic, although the faunal

evidence from Eoforwic reveals that at least some of

its residents had access to fine cuts of meat (al-

though here too they singularly failed to exploit

wild resources). All this might imply a greater diver-

sity of supply to these wics and less than complete

royal control over the activities of its residents. Con-

temporary texts that refer to ecclesiastical landhold-

ing in, and trading from, Lundenwic and the sug-

EMPORIA

ANCIENT EUROPE

329

gestion (based on numismatics) that the bishop of

York may have exercised some authority over “eco-

nomic” activities in Eoforwic open up the possibility

that nonroyal elites may have played a greater part

than previously expected in the functioning of the

emporia.

The discovery that some elite settlements (both

secular and ecclesiastical) in England show evidence

for intensified production from the end of the sev-

enth century (that is, perhaps just before the emer-

gence of the emporia as a phenomenon) raises the

intriguing possibility that their development owed

at least as much to the expansion of regional systems

of production and exchange as to the king’s desire

for overseas exotica. Similarly work since the 1980s

on the continental European economy has empha-

sized that, although emporia like Dorestad were im-

portant and may have linked regional-level produc-

tion and distribution to the acquisition of goods

from overseas, regional networks were structurally

more significant to the development of the Carolin-

gian empire and the Carolingian Renaissance. These

networks were frequently focused on old Roman

cities and castella (forts).

Archaeologists have therefore begun to reassess

the significance of the emporia in the economic and

political development of the polities that made up

early medieval Europe. They were once seen as the

“economic” dynamos of early medieval Europe and

were thought to be central to the reproduction of

kingdoms—they were the places through which

kings controlled the importation of the prestige

goods that secured and maintained alliances and de-

pendents. As the research accumulates, however,

they have come to be viewed as locales articulating

overseas trade with the networks of intensified pro-

duction and exchange being developed around the

(usually nonroyal) elites of northwestern Europe.

To consider how this new insight affects an under-

standing of the demise of the emporia, one must re-

turn to Hodges’s typology.

In fact it can be argued that his type C emporia

are not really emporia at all since they are predicated

on the demise of long-distance trade. In this event

Hodges argues in his Dark Age Economics that “the

emporium could either be abandoned or it could

continue to function within a regional economy.”

The former (abandonment) was the fate of most of

the “classic” emporia, and this generally took place

in the mid– to late ninth century. The Vikings have

been blamed for this, as they have been blamed for

pretty much anything else that went wrong at this

time. They certainly had an effect. Dorestad was

regularly sacked from the 830s and was destroyed

in 863. Lundenwic was attacked in 842 and 851 and

was occupied by a Viking army in 871–872; a deep

ditch dug there in the ninth century might be a

product of these attacks. Viking disruption of long-

distance trade networks may, in fact, have robbed

the emporia of their role in linking regional and in-

ternational “economic” systems. However, one

might also argue, as Adriaan Verhulst does in The

Carolingian Economy, that the emporia’s sudden

extinction and the continuity of “old civitates like

Rouen, Amiens, Maastricht . . . Tournai . . .

[and] younger towns along the rivers (portus) in the

interior” demonstrate how ephemeral wics had al-

ways been. Whatever one’s perspective, emporia

and wics remain among the defining characteristics

of their age, and Dark Age Economics (despite twen-

ty years of critique) still lies at the heart of archaeol-

ogists’ attempts to understand them.

See also Ipswich (vol. 2, part 7); Viking Harbors and

Trading Sites (vol. 2, part 7); Trade and Exchange

(vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bourdillon, Jennifer. “The Animal Resources from South-

ampton.” In Anglo-Saxon Settlements. Edited by Della

Hooke, pp. 177–195. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988. (One

of the first and best discussions of the importance of the

hinterlands of wics, based primarily on the faunal evi-

dence from Hamwic.)

Es, W. A. van. “Dorestad Centred.” In Medieval Archaeology

in the Netherlands. Edited by J. C. Besteman, J. M. Bos,

and H. Heidinga, pp. 151–182. Assen, Netherlands:

van Gorcum, 1990.

Hill, D., and R. Cowie, eds. Wics: The Early Medieval Trad-

ing Centres of Northern Europe. Sheffield, U.K.: Shef-

field Academic Press, 2001. (Updated proceedings of a

conference held in York in 1991.)

Hodges, Richard. Towns and Trade in the Age of Charle-

magne. London: Duckworth, 2000. (See especially

chap. 3.)

———. The Anglo-Saxon Achievement. Archaeology and the

Beginnings of English Society. London: Duckworth,

1989. (See especially chap. 4. A slightly different per-

spective on the emporia, with more on artisanal produc-

tion, but trade and exchange is still central.)

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

330

ANCIENT EUROPE