Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

———. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns and

Trade

A.D. 600–1000. London: Duckworth, 1982. (The

seminal account of early medieval trade and exchange.)

Jensen, Stig. The Vikings of Ribe. Ribe, Denmark: Den antik-

variske Samling i Ribe, 1991. (Much of this short, well-

illustrated book is about the pre-Viking emporium [or

wic] site and the kinds of activities that took place on

these sites.)

Maddicott, John. “Prosperity and Power in the Age of Bede

and Beowulf.” Proceedings of the British Academy 117

(2002): 49–71. (This overview argues for a relatively

prosperous English countryside and emphasizes the sig-

nificance of the production and exchange of cloth in the

eighth century.)

Moreland, John. “The Significance of Production in Eighth-

Century England.” In The Long Eighth Century: Pro-

duction Distribution and Demand. Edited by Inge

Hansen and Chris Wickham, pp. 69–104. Leiden,

Netherlands: Brill, 2000. (Moves away from exchange-

focused perspectives on emporia, arguing that they were

fully integrated into regional economies and may even

have been a product of an intensification of agricultural

production.)

Morton, Alan. “Hamwic in Its Context.” In Anglo-Saxon

Trading Centres: Beyond the Emporia. Edited by Mike

Anderton, pp. 48–62. Glasgow: Cruithne Press, 1999.

(One of a number of excellent papers from a Sheffield

conference that focused on the hinterlands of emporia.)

Peacock, David. “Charlemagne’s Black Stones: The Re-Use

of Roman Columns in Early Medieval Europe.” Antiq-

uity 71 (1997): 709–715. (Makes a convincing case

that Charlemagne’s “black stones” were in fact porphy-

ry columns rather than lava quern stones.)

Verhulst, Adriaan. The Carolingian Economy. Cambridge,

U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2002. (An accessible

discussion of the economy of continental Europe in the

eighth and ninth centuries that stresses the importance

of regional economic networks and sees the emporia as

rather “ephemeral.”)

J

OHN MORELAND

■

IPSWICH

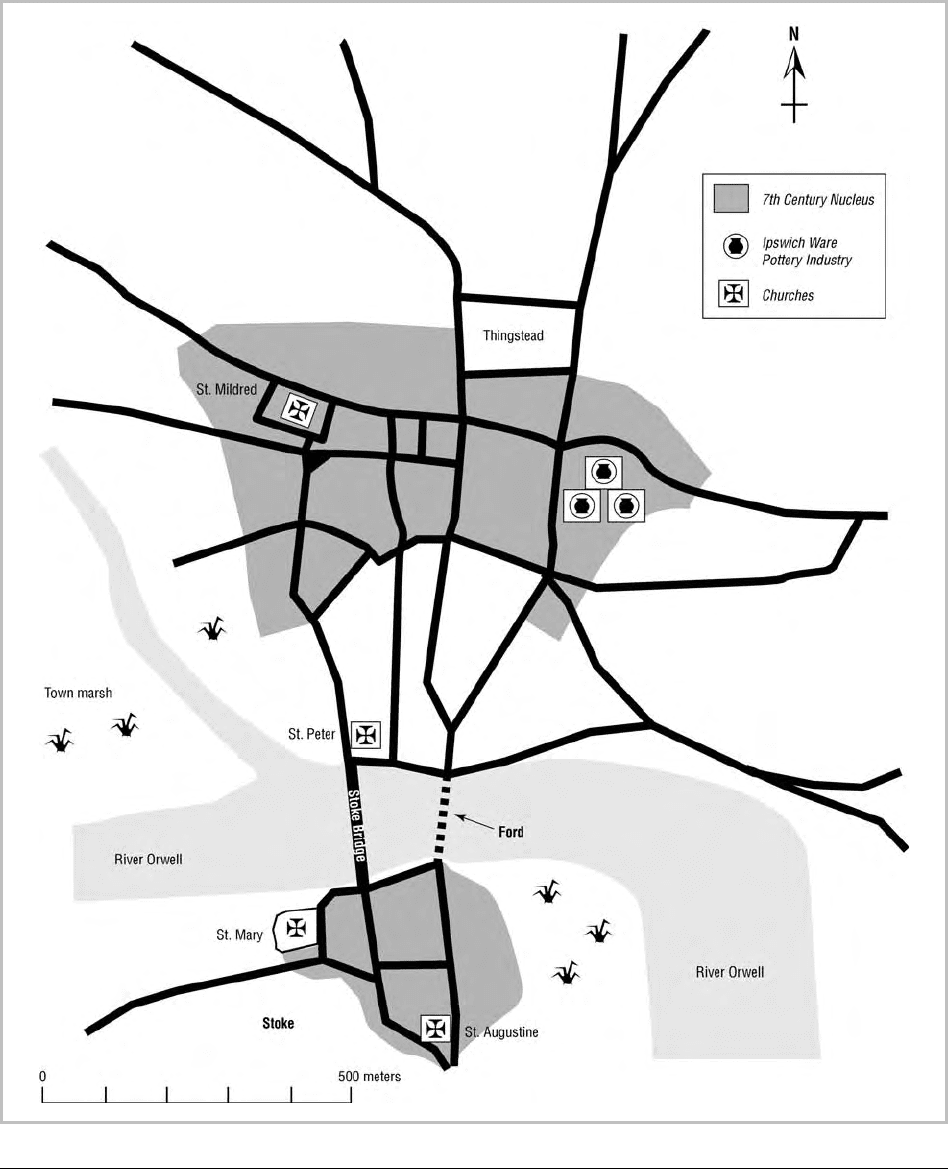

Ipswich lies at the tidal reach of the Orwell estuary,

in southeastern Suffolk, on the shortest crossing of

the North Sea to the mouth of the Rhine. Extensive

archaeological excavations between 1974 and 1990

have shown that the town is one of the four major

craft production and trading settlements of seventh-

to ninth-century England (the so-called wics, or em-

poria). The earliest settlement, dating to the sev-

enth century, appears to have covered up to 15

hectares on the north bank of the Orwell, centered

on the crossing point of the river that later became

Stoke Bridge. Excavations in 1986, west of St.

Peter’s Street, revealed the first structures and rub-

bish pits of this date, associated with local hand-

made pottery and Merovingian (Frankish) black

wares, indicating a trading function. Other sites of

likely seventh-century occupation have produced

few features of this date, but handmade pottery has

been retrieved from later contexts, and a hollowed-

out tree trunk well discovered at Turret Lane, at the

northern limit of the area, gave a dendrochronolog-

ical date (tree ring date) of

A.D. 670 (plus or minus

ninety years).

Other elements of this early settlement also

have been found. Field boundaries containing cere-

al remains were excavated at Fore Street, about 200

meters east of the settlement, indicating an agricul-

tural aspect of the local economy. To the north of

the settlement is an extensive cemetery. Burials of

seventh-century date were excavated at Elm Street

in 1975 and at Foundation Street in 1985. The larg-

est group of burials, however, was excavated in

1988 on the Butter Market site immediately north

of the early settlement. Here seventy-seven graves

were found, despite considerable damage from later

occupation. No limits to the cemetery were discov-

ered, and it was clearly larger than the 5,000 square

meters excavated. Radiocarbon dates indicate that

burial was restricted to the seventh century. Al-

though bone preservation was poor, remains of

more than fifty people were recovered, of which it

is known that thirty-nine were adults and four were

juveniles. Of the adults, research has ascertained

that eight were male or probably male and four were

female or probably female. All the burials were in-

humations, buried with or without coffins in simple

graves, in chamber graves, or under small mounds

surrounded by ring ditches. Objects accompany

nearly half the burials, but the majority of graves

were poorly furnished, often with only a knife. Of

the more lavishly furnished burials, three dating to

the period

A.D. 610–670 were accompanied by

Continental grave assemblages. The richest was a

male buried in a coffin with a sword, shield, two

spears, and two glass palm cups.

IPSWICH

ANCIENT EUROPE

331

Fig. 1. The Middle Saxon emporium of Ipswich. COURTESY SUFFOLK COUNTY COUNCIL.

332

ANCIENT EUROPE

In the early eighth century Ipswich was expand-

ed to a massive 50 hectares by the creation of a vir-

tual new town, to the north of the original settle-

ment, and by expansion south of the river, into

Stoke. New streets were laid out on a gridiron pat-

tern, and buildings were constructed on their front-

ages. Craft activities, including spinning and weav-

ing, antler and bone working, and metalworking,

occur on most sites but not in great quantities.

Leatherworking, too, must have been common but

is represented only on the waterlogged riverfront

site at Bridge Street, where a substantial quantity of

cobblers’ waste was recovered. Other industries,

such as shipbuilding and fishing, also may have been

important, but direct evidence is lacking. There can

be little doubt, however, that the major industry of

the town in both the eighth and ninth centuries was

pottery production. Evidence of pottery production

stretches for about 200 meters on the south side of

Carr Street. Ipswich ware was the only wheel-made

and kiln-fired pottery produced in England between

the seventh and ninth centuries. The industry sup-

plied the entire East Anglian Kingdom with pottery,

and it was exported to aristocratic and ecclesiastical

sites as far away as Yorkshire and Kent. On the mar-

gins of settlement, environmental evidence indi-

cates agricultural activities, including the keeping of

livestock and cereal cleaning, but overall the animal

bone evidence suggests that meat was imported into

the town from the rural hinterland and that Ipswich

was a consumer, rather than a producer, of food.

Little is known about any public buildings that

may have served the Middle Saxon town. The first

Christian churches appear to be associated with the

“new town” of the early eighth century. On the

basis of their dedications, the churches of St. Peter,

St. Augustine, and St. Mildred probably are the ear-

liest. Excavations also have revealed the sequence of

waterfront development. The seventh-century har-

bor looked very different from the present one,

being shallow and tidal, as it is farther down the Or-

well estuary in the twenty-first century. Since the

eighth century there has been continuous land rec-

lamation, as new waterfronts were constructed

nearer the center of the river and the land behind

them was filled, raised, and developed. The Anglo-

Saxon waterfronts were simple timber revetments,

no more than 1 meter high, providing protection to

the river bank and hard standing for unloading

boats.

International trade was important to the Ips-

wich economy throughout the eighth and ninth

centuries. Imported Norwegian hone stones, Rhe-

nish lava millstones, and Frankish pottery are found

on all sites throughout the 50 hectares of occupa-

tion and in quantities far in excess of finds from rural

sites. The dominant trade link is, not surprisingly,

with the Rhine and Dorestad, but there are also

links with Belgium and northern France. It is as-

sumed that wool or cloth was exported in return.

Rhenish imports undoubtedly included wine for

consumption by the local aristocracy and early

church. The wine itself was transported in wooden

barrels, examples of which have been found reused

as lining for well shafts. One such barrel from the

excavations in Lower Brook Street in 1975 has been

dated by dendrochronology to shortly after

A.D.

871 and matches the tree ring pattern of the Mainz

area of Germany.

By the eighth century a handful of towns had

developed around the North Sea and Baltic coast,

each with an economy based on commodity pro-

duction and international trade. In England there is

one such place per Anglo-Saxon Kingdom.

Gipeswic (Ipswich) served East Anglia and certainly

was founded by the East Anglian royal house, the

Wuffingas, whose burial ground at Sutton Hoo and

palace at Rendlesham lie less than 10 miles north-

east of Ipswich, on the east bank of the River

Deben. During the ninth century other towns were

founded in the region (among them Norwich,

Thetford, and Bury St. Edmunds), and Ipswich

gradually lost its role as the East Anglian capital. Al-

though it remained a significant international port,

its economy otherwise became that of a market

town serving southeastern Suffolk.

See also Emporia (vol. 2, part 7); Trade and Exchange

(vol. 2, part 7); Anglo-Saxon England (vol. 2, part

7); Sutton Hoo (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hodges, Richard. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns

and Trade

A.D. 600–1000. London: Duckworth, 1989.

Wade, Keith. “Gipeswic—East Anglia’s First Economic Cap-

ital 600–1066.” In Ipswich from the First to the Third

Millennium, pp. 1–6. Ipswich, U.K.: Ipswich Society,

2001.

———. “The Urbanisation of East Anglia: The Ipswich Per-

spective.” In Flatlands and Wetlands: Current Themes

IPSWICH

ANCIENT EUROPE

333

in East Anglian Archaeology. Edited by Julie Gardiner,

pp. 144–151. East Anglian Archaeology, no. 50. Dere-

ham, U.K.: Norfolk Archaeological Unit, 1993.

———. “Ipswich.” In The Rebirth of Towns in the West,

A.D.

700–1050. Edited by Richard Hodges and Brian Hob-

ley, pp. 93–100. Council for British Archaeology Re-

search Report, no. 68. London: Council for British Ar-

chaeology, 1988.

K

EITH WADE

■

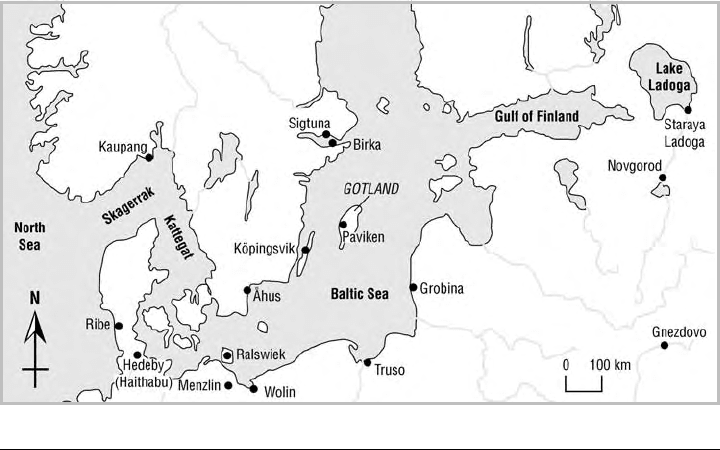

VIKING HARBORS AND

TRADING SITES

Our understanding of the harbors and centers of

trade dating to the Viking Age is limited, as is infor-

mation concerning the level and scope of trade and

its organization. The difficulty of acquiring and as-

sessing such information stems from the fact that

most trading points are known only from scant writ-

ten records—none of which are from the Viking

homelands themselves. A map of the known Viking

harbors and towns in the Baltic area shows very few

places, sparsely situated. The best examples of early

trading centers in the Baltic Sea are Birka (Sweden),

Hedeby or Haithabu (Germany), Grobin (Latvia),

Wolin (Poland), and Novgorod (Russia). These

centers, known from written documents or discov-

ered by chance, give a much too simple picture of

the true state of affairs.

Indeed, along the Baltic coast there must have

been a vast number and variety of harbors and trad-

ing sites of all sizes, from small fishing camps to per-

manently occupied cities. Surprisingly, there are no

confirmed harbors and trading centers, for example,

along the eastern coast of Sweden, despite the fact

that this region is one of the largest, oldest, and

most important cultivated areas in all of Sweden.

This situation is more or less mirrored along the

eastern Baltic shore as well as along the Norwegian

coast. The challenge, then, is to identify the spots

not mentioned in written sources, with archaeologi-

cal fieldwork as our best guide.

The island of Gotland provides good examples

of previously unknown harbors. Situated in the

middle of the Baltic Sea, it was a true center in the

Viking world. Nowhere have so many Viking silver

hoards been found as on this tiny island. In all, more

then seven hundred separate caches of silver and

gold give clear evidence of the island’s widespread

trade connections. Despite the even distribution of

this treasure (mostly Arabic coins) over the island,

only one known harbor on Gotland dated to the Vi-

king Age—Paviken, on the west coast. It is unlikely

that all the hoards could have been distributed over

the island from just one harbor. There must have

been many more.

Excavation of this site took place at the end of

the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s. Starting

in the last decade of the twentieth century an exten-

sive project was carried out on Gotland, with the

aim of analyzing and describing the numbers of har-

bors and trading sites and their structure, develop-

ment, and spatial organization during the period of

approximately

A.D. 600–1000. The research was

conducted using a combination of methods, both

notes and maps in museum archives and field

studies. Three main criteria have been used as evi-

dence to locate possible harbors: prehistoric graves

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

334

ANCIENT EUROPE

Some Viking harbors and towns in the Baltic Sea region.

or grave fields close to the coast, a shore protected

from strong winds, and a situation in the cultural

landscape diverging from the normal—for instance,

a point where cadastral maps show that several roads

converged.

The next step in the project involved phosphate

mapping of suspected locations. This mapping

identified about sixty places along the Gotlandic

coast that showed signs of major or minor activities

during the Viking Age. Evaluation of these finds in-

dicated many places that can be interpreted as larger

harbors or trading sites, distinguishable from the

others in their rich and varied number of artifacts.

Boge, Bandlunde, Fröjel, Paviken-Västergarn, and

Visby belong to this category. Other, smaller places

seem to be fishing harbors for the farmers on the is-

land.

The most extensive investigations of one of

these previously unknown Viking trading and man-

ufacturing sites were conducted between 1998 and

2002 at Fröjel, along the west coast of Gotland. At

this spot there is an area of 60,000 square meters

with many traces of buildings and several grave

fields. The archaeological excavations have revealed

a harbor and trading center that was active from the

late sixth century to approximately

A.D. 1180. The

harbor’s activities peaked during the eleventh cen-

tury and into the beginning of the twelfth century.

Here is ample documentation of intensive trade

and manufacturing—a harbor with connections

both west and east. Coins from Arabia, England,

Germany, and Denmark, and jewelry from places as

far-flung as the North Atlantic (walrus ivory), the

Black Sea (rock crystal), and the area of Kiev in

modern-day Ukraine (a resurrection egg) give evi-

dence of distant trade.

The example of Gotland shows clearly that the

system of harbors and trading centers in the Viking

Age was far more complicated and intricate than

one is led to believe from written sources. Jens Ul-

riksen did the same type of investigation in Den-

mark in 1997, with more or less the same conclu-

sions. The picture derived solely from written

sources is thus far from complete. To understand

fully trade and travel patterns in the Viking Age, one

must combine the written sources with extensive ar-

chaeological fieldwork.

See also Trade and Exchange (vol. 2, part 7); Viking

Ships (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carlsson, Dan. “Ridanäs”—Vikingahamnen i Fröjel

[“Ridanäs—the Viking Age harbor in Fröjel]. Visby,

Sweden: ArkeoDok, 1999.

Clark, Helen, and Björn Ambrosiani. Towns in the Viking

Age. Rev. ed. Leicester, U.K.: Leicester University

Press, 1995.

“Fröjel Discovery Programme.” Gotland University Col-

lege. http://frojel.hgo.se.

VIKING HARBORS AND TRADING SITES

ANCIENT EUROPE

335

Graham-Campbell, James, Colleen Batey, Helen Clarke,

R. I. Page, and Neil S. Price. Cultural Atlas of the Vi-

king World. New York: Facts on File, 1994.

Hodges, Richard. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns

and Trade AD 600–1000. 2d ed. New York: St. Mar-

tin’s, 1982.

Ulriksen, Jens. Anlo

⁄

bspladser: Besejling og bebyggelse i Dan-

mark mellem 200 og 1100 e.Kr. [Seafaring, landing sites,

and settlements in Denmark from

A.D. 200 to 1100].

Roskilde, Denmark: Vikingeskibshallen i Roskilde,

1997.

D

AN CARLSSON

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

336

ANCIENT EUROPE

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

DARK AGES, MIGRATION PERIOD, EARLY MIDDLE AGES

■

The Middle Ages are sandwiched between the era

of classical antiquity and the modern world. The be-

ginning of the Middle Ages is traditionally marked

by the fall of the Western Roman Empire in

A.D.

476, while Columbus’s voyages of discovery mark

the start of the modern period. Therefore, most

scholars consider the interval between the fifth and

the fifteenth centuries

A.D. as the Middle Ages or

the medieval period.

Most historians, art historians, and archaeolo-

gists subdivide the Middle Ages into an earlier and

a later period. The Late or High Middle Ages begin

in the 11th century

A.D. By this time, the Vikings

had colonized Iceland and Greenland, and Chris-

tianity had been adopted throughout most of cen-

tral and northern Europe. The High Middle Ages

are marked by the growth of urbanism across Eu-

rope, the expansion of long distance trade networks,

the construction of the great cathedrals, and the es-

tablishment of nation-states. Historical records pro-

vide valuable information on later medieval life.

These European societies of the High Middle Ages

have many features in common with the ancient

Egyptians, the Maya, and other groups known as

civilizations or complex societies. Therefore, the ar-

chaeology of the High Middle Ages is not included

in this encyclopedia.

The earlier parts of the Middle Ages, on the

other hand, have much more in common with the

barbarian societies of later prehistoric Europe.

These societies were primarily rural and agricultural,

and their documentary records are limited or non-

existent. As a result, much of what scholars have

learned about day-to-day life in the earlier Middle

Ages in Europe comes from archaeological surveys

and excavations.

Three terms—the Early Middle Ages, the Mi-

gration period, and the Dark Ages—have been used

to describe the earlier parts of the medieval period.

Each term has a slightly different meaning, and the

terms can be used differently in different parts of

Europe.

EARLY MIDDLE AGES

The Early Middle Ages is a term that commonly is

used by art historians and others to describe the pe-

riod beginning with the collapse of the Western

Roman Empire in the fifth century and ending with

the rise of the Romanesque style of architecture in

the eleventh century. While the term might appear

as a straightforward chronological marker, it is most

useful in describing regions that were formerly part

of the Western Roman Empire. In regions such as

Britain, France, and Spain, the replacement of

Roman military, political, and economic authority

by the barbarian successor kingdoms led to signifi-

cant social, economic, and political changes. Out-

side the Roman Empire, however, in regions such

as northern Germany and Scandinavia, the first part

of this period represents a continuation of the Iron

Age way of life. In much of northern Europe, the

first four centuries

A.D. are referred to as the Roman

Iron Age, while the period c.

A.D. 400–800 is often

termed the Late or Germanic Iron Age. In many

parts of northern Europe, the term “medieval” is

used only when referring to the period after

A.D.

ANCIENT EUROPE

337

1000, an era that is outside the scope of this ency-

clopedia.

DARK AGES

The term “dark age” generally is used to indicate a

period of time when historical records are limited or

nonexistent. For example, the Greek Dark Age be-

gins with the collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms

around 1200

B.C. and ends with reappearance of

writing in the eighth century

B.C. Historians in the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

A.D. used the

term Dark Ages to refer to almost all of the Europe-

an Middle Ages, from the fifth through the twelfth

centuries

A.D., and they used the term in a pejorative

sense. For these historians, the earlier medieval peri-

od was not just a time of limited literacy and few

documentary sources; it was a period of intellectual

stagnation; the accomplishments of medieval peo-

ple were deemed far less impressive than those of

classical antiquity and the Renaissance. Although

there is no question that few contemporary histori-

cal sources survive from early post-Roman western

Europe, the use of the term Dark Ages is still prob-

lematic for two reasons. First, most of northeastern

Europe remained nonliterate, essentially prehistor-

ic, throughout almost the entire first millennium

A.D. The Baltic regions were well outside the

boundaries of the Roman Empire, and these lands

were mentioned only peripherally in Greek and

Roman sources from the first half of the first millen-

nium

A.D. Literacy was introduced to the Baltic re-

gions along with Christianity around the year 1000.

Second, the term Dark Age is particularly inappro-

priate for Ireland between the fifth and the eighth

centuries

A.D. Christianity and literacy were intro-

duced to Ireland in the 400s. Over the next three

centuries the Irish developed the oldest indigenous

literary tradition in Europe outside Greece and

Rome. Some writers would even suggest that the

Irish monks who copied classical manuscripts in

their scriptoria actually saved Western Civilization.

Irish archaeologists generally refer to the fifth

through eighth centuries in Ireland as the Early

Christian Period.

Many archaeologists today avoid the use of the

term Dark Ages because of its former pejorative

connotations. When the term is used, it usually de-

scribes post-Roman societies whose social, political,

and economic organization differ significantly from

the classical world; and it often refers only to the ini-

tial part of the Early Middle Ages, usually the fifth

to the eighth centuries

A.D. Since few historical

sources are available to study the economics and

politics of the early post-Roman period, archaeolo-

gy has a crucial role to play in the study of this era.

MIGRATION PERIOD

The Early Middle Ages are sometimes described as

the Migration period. In many ways, the first half of

the European Middle Ages can be seen as one ex-

tended interval of migration. The period begins

with the movement of barbarian tribes, such as the

Huns, into the territory of the Roman Empire dur-

ing the fifth century

A.D. After the fall of the West-

ern Roman Empire, a series of barbarian successor

kingdoms were established in the former imperial

territory. These include the kingdoms of the Franks

in France, the Visigoths in Spain, the Langobards

(Lombards) in Italy, and the Angles and Saxons in

southern and eastern Britain. The homelands of

these barbarian tribes were located outside the em-

pire, in northern and eastern Europe. Migrations,

however, did not cease with the establishment of

these successor kingdoms. The Magyars entered the

Carpathian Basin in the eighth century, and the

Early Slavs expanded into much of east-central Eu-

rope in the sixth and seventh centuries

A.D.

Perhaps the best known of all the migrating

peoples are the Vikings. Beginning in the late eighth

century

A.D., Vikings from western Scandinavia

began to raid, trade, and colonize many regions of

the North Atlantic. Norse settlements are well doc-

umented in both Britain and Ireland. The Vikings

had colonized Iceland by the late ninth century, and

about a century later they established two colonies

in southwestern Greenland, the westernmost out-

post of the medieval European world. Other Vi-

kings migrated eastward, settling in Russia and trad-

ing with locations as far away as Constantinople

(Istanbul) and Mesopotamia.

Although migration is a fundamental feature of

European society between

A.D. 400–1000, the Mi-

gration period, in the strictest sense of the term, re-

fers to the period between 400–600, when a series

of Germanic kingdoms were established in the terri-

tory of the former Western Roman Empire. Unlike

the term Dark Ages, Migration period does not

carry with it a pejorative connotation. For that rea-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

338

ANCIENT EUROPE

son, many scholars prefer it to Dark Ages when dis-

cussing the early centuries of the Middle Ages.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cahill, Thomas. How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Un-

told Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome

to the Rise of Medieval Europe. New York: Nan A.

Talese, Doubleday, 1995.

Hodges, Richard. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns

and Trade

A.D. 600–1000. 2d ed. London: Duckworth,

1989.

Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Eu-

rope,

A.D. 400–600. Translated by Edward James and

Columba James. University Park: Pennsylvania State

University Press, 1975.

P

AM J. CRABTREE

DARK AGES, MIGRATION PERIOD, EARLY MIDDLE AGES

ANCIENT EUROPE

339

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY

■

The distinction between the fields of history and ar-

chaeology is widely recognized to be a result of the

scholarly boundaries that place historians and ar-

chaeologists in separate academic departments. The

hindrance of intellectual exchange between the dis-

ciplines has resulted in the development of misun-

derstandings about philosophical underpinnings,

standards of practice, and current inquiry. More-

over, this division between history and archaeology

naturalizes modern distinctions between the pasts

of literate and nonliterate people. Indeed, a thor-

ough assessment of the relationship between history

and archaeology requires an appraisal of the nature

of historical and archaeological inquiry, as scholars

in each field exhibit fundamental misconceptions

about the other discipline.

LITERACY IN EARLY

MEDIEVAL EUROPE

Traditionally, the division between “prehistoric”

and “historic” archaeology, with its evolutionary

implications, has been based on the presence of

writing. In modern studies of the early medieval pe-

riod, however, this distinction often is obscured, be-

cause literate groups, such as the members of the

Latinized Christian church, may provide the names

and histories by which we know either contempora-

neous nonliterate peoples or groups whose symbol-

ic expression remains undeciphered by modern

scholars. The archaeology of these peoples has been

termed by some scholars “protohistory.” The

distinction between peoples who produced written

records and those who did not underlies the privi-

leged position ascribed to literacy as defining an

evolving “civilization” and nonliteracy as represen-

tative of an ahistorical “barbarism.”

In a society with limited literacy, such as early

medieval Europe, writers generally were drawn

from and read by only a small, usually elite, segment

of society. Literacy was restricted geographically to

religious and urban centers. It is important to ac-

knowledge that documentation is in itself an agent

of cultural transformation, as records play a role in

the material discourse of power. During the early

medieval period, an apparent association with the

supernatural afforded an otherworldly authority to

the documents created in religious scriptoria.

Documents often were created to maintain and

further the economic and administrative interests of

certain constituencies. For example, the Ecclesiasti-

cal History of the English People (Historia ecclesiasti-

ca gentis Anglorum), written in the first third of the

eighth century by the Northumbrian cleric the Ven-

erable Bede, and the sixth-century History of the

Franks (Historia Francorum), by the bishop Grego-

ry of Tours, consciously or unconsciously legiti-

mized the nation-building endeavors of their re-

spective kings, Edwin and Clovis, within the

emerging English and Frankish states. These histo-

ries presented a spurious political unity that implied,

for the benefit of their readers, that these nascent

states manifested a cultural homogeneity. Archaeol-

ogists seeking a corresponding agreement in materi-

al culture patterning must be aware that the docu-

ments that direct their interpretations can be

misleading. Attempts to relate the tribal groupings

recorded in early medieval historical records perpet-

340

ANCIENT EUROPE