Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

TRADE AND EXCHANGE

■

The changing European economy between A.D.

400 and 1000 lies at the nexus of several trajectories

of cultural transformation. The major transition

from the Roman world to the medieval world is ech-

oed by the geographically ever diminishing econo-

my, from a large-scale interregional trade network

to smaller spheres of exchange. In addition, the

context of trade within what once had been Roman

provinces differed from areas that had been inside

the Roman sphere of interaction but outside the

Roman purview. Changing connections, changing

trade routes, changes in the social, economic, and

political context of the marketplace are important

considerations. Although historical records give se-

lectively (or arbitrarily) preserved glimpses into

these problems, only archaeology can reveal the

whole picture, from crafts workshops to market-

place organization, from trade routes to the pat-

terns of interaction between the public, artisans,

merchants, and elites of the successor states.

ORIGINS AND CONTEXT OF EARLY

MEDIEVAL TRADE

Local trade in early medieval Europe is a continua-

tion of a long tradition of exchange stretching back

into prehistoric times, but one of the distinguishing

attributes of trade in the Iron Age, Roman era, and

Early Middle Ages was the increased mobility of

people and goods. Exchange of some type over rela-

tively long distances dates to the Paleolithic, and

while recent isotopic analysis of Neolithic skeletons

suggests that early farmers were more mobile than

previously thought, their travel from upland to low-

land and along river valleys was aimed at settling in

new places. In the Bronze Age most trade was local,

but rare substances, such as bronze and amber,

clearly were moved over long distances. Outside the

Mediterranean, where trade was organized profes-

sionally, goods probably were traded hand to hand

by many intervening individuals.

The Iron Age saw a transition to trade as a regu-

lar, major part of the subsistence and political econ-

omies of European polities. This was due in part to

heightened political interactions and improved

transport technology, especially in shipping. As in

earlier times, Iron Age elites probably controlled

importation of luxuries that helped maintain their

community status. Later, while still controlling pro-

duction and trade of the most valuable items, they

lost their monopoly over the creation and dissemi-

nation of other goods, and the continuing trend

from generalist farmers toward economic specializa-

tion in various trades and occupations created an ar-

tisan class and a market for their output. In the

Celtic Iron Age, populous proto-urban oppida set-

tlements of continental Europe continued to be the

destination for exotic goods. Attached craft special-

ists created indigenous prestige objects of outstand-

ing beauty for their elite masters, even as others pro-

duced less spectacular goods for local exchange and

consumption: ceramic vessels, metal tools, and

items of clothing and adornment. Eventually, the

urban societies of the Iron Age Mediterranean cul-

minated in the market economy of the Roman Em-

pire, where each year professional merchants trans-

ported hundreds of thousands of tons of goods in

large cargo ships. A vast trading system with com-

ANCIENT EUROPE

351

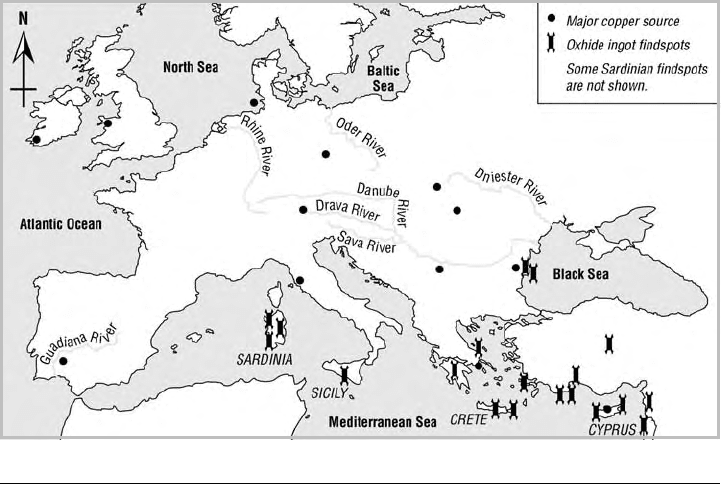

Major copper sources and oxhide ingot findspots.

plex rules and regulations crisscrossed the empire

before its decline.

Thus, a combination of earlier trade and ex-

change traditions combined with the legacy of the

Romans influenced the development of early medi-

eval markets. Post-Roman trade varied regionally,

depending on whether an area had been part of the

former Romanized core, a less Romanized prov-

ince, such as England or Germania, or a region,

such as Scandinavia or the Slavic lands, that was out-

side the empire but regularly interacted with Rome.

The Roman Empire stretched from Syria to

Scotland, but daily governance was conducted at a

local level. A Roman civitas and its hinterland made

up a highly autonomous administrative unit, orga-

nized loosely under a provincial governor with a

military contingent. When the greater Roman entity

became unstable, provinces grew even more auton-

omous, eventually breaking into regions and then

subregions. The post-Roman era is known for its

migrations and incursions, as non-Roman outsiders,

customarily called barbarians, invaded and seized

these fragments of the empire. Many Europeans

outside the Roman sphere were content to stay at

home, but even so their local economies were af-

fected deeply by the decline of the imperial system.

Thus, the question of continuity between the late

Roman and early medieval economies during this

period of unimaginable change is an important

issue.

THEORIES ON TRADE

AND EXCHANGE

The debate has long simmered over urbanism,

trade, and markets in post-Roman Europe. Early-

twentieth-century historians, most notably Henri

Pirenne, combined the documentary record with

deductive impressions about the origins of feudal-

ism to formulate several plausible hypotheses about

urbanization, markets, and long-distance trade in

the post-Roman world. Pirenne’s influential thesis

proposed that the Roman organization of Europe

was never dismantled but persisted far into the me-

dieval period. Only as European trade with the

Mediterranean was cut off by Muslim expansion in

the seventh century did Germanic rulers of the Dark

Ages, such as Charlemagne and his contemporaries,

slowly expand their regions’ agricultural economies.

The refutation of this theory and a new under-

standing of markets, money, and manufacturing

during the barbarian age have come about largely as

the result of the revelations of modern archaeology.

The twentieth century saw dramatic changes in

urban and marketplace excavation methods. Early

civic projects in European towns were conducted by

workmen clearing arbitrary layers, keeping sketchy

records of the curiosities they unearthed. After

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

352

ANCIENT EUROPE

World War II, archaeologists working in bomb-

damaged cities primarily used trenches for investiga-

tion. As they looked at small bits of deep strata, they

could detect a long and complex history at a partic-

ular site, and could even date the strata, but they

were unable to observe the “big picture.” Only in

the last decades of the twentieth century, when hor-

izontal excavation became dominant, could large-

scale exposure of former surface areas uncover many

contemporary structures, features, artifact scatters,

and boundaries as well as their patterning and con-

text. By the 1980s archaeologists began to chal-

lenge earlier ideas about the complex economics of

the early Middle Ages.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FOR

TRADE AND EXCHANGE IN FORMER

IMPERIAL EUROPE

The provinces of Rome had a busy market economy

based on import, export, and manufacturing. Trade

between provinces was facilitated by shared tradi-

tions, rules, and regulations within a single political

economy. As the empire’s troubles deepened

through the course of the fifth century, could pro-

ducers and consumers maintain the convenience of

customary trade, or were they forced or encouraged

by changing conditions to find new economic solu-

tions? Archaeological investigations around the

Mediterranean and Europe have shown that in con-

trast to Pirenne’s idea of post-Roman continuity, by

the late fifth century the Roman world was in de-

cline, leaving a vacuum in which the provinces be-

came disconnected and transformed into regional

and subregional systems and in which markets

largely lost their character as interregional and long-

distance trade centers.

While post-Roman primary documents exist,

perhaps the socioeconomic crises are best seen

through archaeological evidence. During the impe-

rial era, Rome’s Campus Martius was a beautifully

planned and maintained monumental landscape. In

addition to parade grounds, it held temples, porti-

coes, baths, the stadium, circus, and several theaters

for public enjoyment. By the late fifth century it was

despoiled: squatters and craftspeople were camped

out in shantytowns within the ruins. One excavation

found a glassmaker’s stall of the fifth or sixth centu-

ry supplanted in the seventh or eighth century by a

workshop manufacturing religious objects for the

clergy and local markets. The extremely local and

limited nature of trade, compared with earlier times,

is illustrated by the fact that imported items came

from no farther than Sicily. Another indicator of

economic decline is coinage. Between the seventh

and eighth centuries alone, gold coins dropped

from 90 percent to 10 percent content and silver

from 70 percent to less than 30 percent, and bronze

coins were as thin as paper.

At sites elsewhere in Italy dating to the fifth to

seventh centuries, commercial harbors were aban-

doned, and there is a strong decline in import-trade

amphora from Africa and the eastern Mediterra-

nean, indicating that interregional trade had col-

lapsed. On the Adriatic at fifth-century Butrint, for-

tifications were built against barbarian invaders,

palaces were left unfinished, and squatters moved

in. Merchants occupied the ruined forums of other

towns across Roman Europe, creating makeshift

workshops in the rubble of former citadels. While

Rome and a few other southern cities maintained a

modicum of urban character, western European

towns and markets were largely abandoned. Long-

distance commercial exchange and the interregional

market system had ceased operation.

TRADE, EXCHANGE AND MARKETS

OUTSIDE THE FORMER EMPIRE

Archaeological evidence shows regular, active trade

between Romans and non-Romans before

A.D. 400.

In return for elite goods—swords, adornments,

wine and serving vessels—non-Roman peoples ex-

ported utilitarian wares, such as leather, hide, food-

stuffs, and slaves. Modern excavations at elite-

controlled ports, such as Gudme-Lundeborg in

Denmark, usually show a chieftain’s compound

with a complement of craftspeople and a harbor

during the Roman era.

Rulers in barbarian regions thus became highly

dependent on Roman goods for maintaining their

social status. After Rome’s troubles began and the

imperial system began to totter, Roman goods dis-

appeared from these sites, as long-distance trade was

curtailed. Despite the cutoff of Roman items, local

rulers still needed to impress their peers and over-

awe their subjects, so the trade in elite goods could

not be allowed to end. Instead, smaller, less ambi-

tious trade networks were formed between the

upper classes in Britain, the Low Countries, Scandi-

navia, and Germanic and Slavic regions. Trade con-

TRADE AND EXCHANGE

ANCIENT EUROPE

353

tinued at some Roman-era places; more important,

however, between

A.D. 700 and 1000 a series of

new, specialized sites combining crafts production

with a trading center appeared. Among them were

Ipswich and Hamwic in Britain; Birka, Ribe, Kau-

pang, and Hedeby in Scandinavia; Quentovic in

northern France; Dorestad on the Dutch Rhine;

Staraya Ladoga in Russia; and Wolin in Poland.

Similar sequences are found in the Czech Republic

and northern Germany.

These markets, commonly referred to as empo-

ria, were not the spontaneous efforts of merchants

and manufacturers. Local rulers’ involvement is ap-

parent in elite-built and maintained fortifications,

indicating royal administration and protection, at

emporia such as Hedeby, Ipswich, and Hamwic.

Ribe and Löddeköpinge in Denmark and Sweden,

respectively, had nondefensive boundary markers

that probably delimited the area of regulated trade.

At Mikulcˇice in the Czech Republic and at Ham-

burg, Lübeck, and Brandenburg, Germany, excava-

tions show that local chieftains established fortress-

like residences with attached craftspeople in the

eighth century, after which non-elite settlements

developed around them, leading to urban market-

places.

Eventually, less luxurious local items were made

and traded at these sites, probably because the taxes

that kings could collect in a regulated royal market

became as important as acquiring their own sump-

tuary goods. Anglo-Saxon texts confirm that be-

tween

A.D. 700 and 1000 there was a steady rise in

tolls and tariffs on trade. While such documentation

is found only in England, scholars believe this was

paralleled throughout the emerging successor

states, providing a substantial royal income. As

these states became important trading powers, new

trade routes sprang up, including the Roman-era

Rhine-Rhône river route between north and south,

which served new trading places, such as Frisian

Dorestad on the Rhine, and Roman-Baltic connec-

tions via the Oder (Viadna), Dnieper, Dniester, and

Prut, the Elbe, Weser (Visurgis), and Eider grew ac-

tive, serving Hedeby, Hamburg-Bremen, Lübeck,

and Wolin. Sea routes continued to connect Atlan-

tic Europe with Britain, and new sea-lanes linked

Dorestad, Ribe, and Hedeby with emporia in Swe-

den and Norway.

NEEDFUL THINGS AND OBJECTS

OF DESIRE

Despite the importance of trade to people in the

Middle Ages, textual references to early medieval

trade remain fairly sparse. Thus, the archaeological

examination of ships, wharves, workshops, ware-

houses, and market organization sometimes is the

best option for studying the manufacturers, mer-

chants, and middlemen whose activities were trans-

forming Europe. Through many extensive excava-

tions, archaeologists have discovered what goods

were coveted by both rulers and commoners. Pre-

cious metals and gems were reserved primarily for

the royal and upper classes, as were fine imports of

ceramic and glass, wine, textiles, and weapons. Lo-

cally produced adornments were skillfully made and

available to a larger group of well-off citizens. Pro-

duction of non-luxury items used by the broader

populace is evident, and each trade had its unique

artifact assemblage. Weaving tools and loom parts

are common, as is the debris from workshops manu-

facturing combs and pins, in the form of sawed-off

bone and horn fragments and partially finished

products. Metal casting leaves fragments of cruci-

bles and molds, brooches, and fasteners. Iron yields

large amounts of slag, iron bars and rods, tool pre-

forms (blank, pre-formed and unfinished tools),

and, in some cases, the tongs and hammers of

smiths. Advanced glass industries are evidenced by

molten glass wasters and deposits of malformed

glass beads; in one case, at the Danish trading site

of Dankirke, archaeologists discovered a warehouse

of glass drinking horns that had been destroyed by

fire. Some sites yield butchered animal and fish

bones from purveyors of foodstuffs, and thick dung

layers indicate trade in live cattle. Coins, scales,

weights, and moneybox keys sometimes are present.

Marketplaces often are ephemeral, with struc-

tures resembling fairground stalls and booths. Col-

lections of sunken floored huts often are evident,

and at Löddeköpinge, Sweden, the seasonal nature

of the marketplace is seen in alternating occupation-

al layers and sterile sand in the floors of these pit

houses. On the other hand, many markets were per-

manent, with continuous occupations by specific

workshops and industries. At Ribe and Hedeby,

workshop boundaries and property divisions were

maintained without change for many generations,

reflecting long-term regulation, while the channel-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

354

ANCIENT EUROPE

ing of streams and the gridlike layout of streets and

blocks show central planning at Hedeby.

By the end of the first millennium, long-

distance and local trade in luxury and non-luxury

goods was vital to the economies of medieval states.

Taxes and regulations remained, but the specially

constructed and maintained royal trading emporia

disappeared. They were either supplanted by or

transformed into urban markets within the cities of

later medieval Europe.

See also Emporia (vol. 2, part 7); Ipswich (vol. 2, part 7);

Staraya Ladoga (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Callmer, Johan. Production Site and Market Area: Some

Notes on Field Work in Progress, 1981–2. Lund, Sweden:

Meddelanden fra˚n Lunds Universitets Historiska Muse-

um (1983): 135–165.

Clarke, H., and B. Ambrosiani. Towns in the Viking Age. Lei-

cester: Leicester University Press, 1991.

Fehring, Günter P. The Archaeology of Medieval Germany:

An Introduction. Translated by Ross Samson. London:

Routledge, 1991.

Frandsen, L., and S. Jensen. “Pre-Viking and Early Viking

Age Ribe.” Journal of Danish Archaeology 6 (1988):

175–189.

Hedeager, Lotte. Iron Age Societies: From Tribe to State in

Northern Europe, 500

BC to AD 700. Translated by John

Hines. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

Hodges, Richard. Towns and Trade in the Age of Charle-

magne. London: Duckworth, 2000.

———. “Emporia, Monasteries, and the Economic Founda-

tion of Medieval Europe.” In Medieval Archaeology: Pa-

pers of the Seventeenth Annual Conference of the Center

for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies. Edited by

Charles L. Redman. Binghamton, N.Y.: State Universi-

ty of New York, 1989.

———. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns and

Trade

AD 600–1000 London: Duckworth, 1982.

Randsborg, Klavs. The First Millennium

AD in Europe and

the Mediterranean. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, 1991.

Sawyer, P. “Early Fairs and Markets in England and Scandi-

navia.” In The Market in History. Edited by B. L.

Latham and A. J. H. Anderson, pp. 59–77. London and

Dover, N.H.: Croom–Helm, 1986.

Schietzel, K. “Haithabu: A Study on the Development of

Early Urban Settlement in Northern Europe.” In Com-

parative History of Urban Development in Non-Roman

Europe: Ireland, Wales, Denmark, Germany, Poland,

and Russia from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century.

Edited by H. B. Clark and A. Simms. BAR International

Series, no. 255. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports,

1985.

Wells, Peter S. “The Iron Age.” In European Prehistory: A

Survey. Edited by Sarunas Milisauskas, pp. 335–383.

New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers,

2002.

T

INA L. THURSTON

TRADE AND EXCHANGE

ANCIENT EUROPE

355

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

COINAGE OF THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

■

In the early centuries of the first millennium A.D. the

borders of the Roman Empire divided Europe into

two monetary zones: (1) a southern and western

zone, in which coins were minted and circulated

more or less regularly as an intrinsic part of the

economy, and (2) a northern and eastern zone,

which made no coins of its own and imported coins

sporadically as a result of various interactions, eco-

nomic and otherwise. This same monetary division

of Europe, following approximately the valleys of

the Rhine and Danube Rivers, survived the political

dissolution of the Roman Empire and was main-

tained almost until the end of the millennium. It

was only in the ninth century and especially the

tenth century that lands beyond the Roman imperi-

al frontiers began to produce their own coins to

supply a monetized economy.

ROMAN COINAGE IN EUROPE

Coinage was unified throughout the western

Roman Empire, with mints scattered across Europe

producing coins of various denominations of gold,

silver, and copper. Minting, like many other aspects

of the Roman state, went through a period of disar-

ray in the third century, to be revived and regular-

ized by the reforms of the Roman emperors Diocle-

tian and Constantine I around

A.D. 300. The

regular mints of Europe for the next two centuries

included Lyons and Arles in Gaul; Trier in Rhine-

land Germany; Rome, Milan, Ravenna, and

Aquileia in Italy; Siscia (modern-day Sisak) in Pan-

nonia; and Thessalonica (now Salonika) in Greece.

Spain, which had been an important source of bul-

lion in the earlier empire, lacked a mint in the later

period, as did England after the closing of the mint

of London in

A.D. 325.

The standard coin of the late empire was the

gold solidus, which was of pure alloy and an un-

changing weight of 24 karats, or

1

⁄

72

of the Roman

pound (4.5 modern grams), from its introduction

in

A.D. 309 well into the tenth century, by which

time it was called a nomisma. Fractions of the soli-

dus also were minted; in the west the third, or

tremissis, was most common (fig. 1). The silver de-

narius had been the basis of the Roman monetary

system during the republic and early empire, but in

the fourth and fifth centuries silver coinage was rare.

Copper coinage was relatively common, of varying

weights and denominations. By the fifth century as

many as 7,200 copper nummi were needed to buy

a gold solidus, with no intermediate denominations

available. The obverse of late Roman coins generally

bore the image of the reigning emperor, with his

name and honorific titles making up the surround-

ing legend. On the reverse pagan deities gradually

gave way to generalized symbolic representations of

Roman virtues and scenes of the emperor in military

contexts; explicitly Christian imagery was rare.

Beyond the frontiers delimited by the limes, or

boundaries, along the Rhine and Danube Rivers,

Roman coinage was a familiar phenomenon, espe-

cially to those in direct contact with the empire. The

frontier regions themselves constituted a heavily

monetized zone, with coins exchanged to provide

for the needs of the soldiers garrisoned there and to

pay for commodities imported across the border.

Military payments also fueled the export of Roman

356

ANCIENT EUROPE

coinage beyond the frontiers in the form of salaries

to individual barbarian soldiers who returned home

after service in the Roman army and as payments to

federated bands of warriors from outside the empire

who were enlisted into its campaigns. Coins also

were exported as tribute to barbarian leaders and

were carried back home among the booty gained on

cross-border raids.

The export of Roman coins to barbarian Eu-

rope is attested to by archaeological finds through-

out the north and east of the Continent. For the

most part copper coins are found nearest to the

frontiers, chiefly as stray losses on excavated habita-

tion sites. Gold coins are encountered farther afield,

usually buried in hoards varying from a few coins to

thousands. Some of these hoards, chiefly in the area

north of the Danube, have been identified as salary

payments to individual soldiers and as blocks of trib-

ute to such groups as the Huns. Solidi found in

Scandinavia constitute a less-clear class of exports;

these coins cluster in the period

A.D. 454 to 488 and

have been interpreted variously as the result of a

trade in furs and slaves or sums sent north by feder-

ates and invaders.

THE COINAGES OF THE EARLY

GERMANIC STATES

The coins produced by the Germanic rulers who

succeeded the Roman emperors in Europe followed

the form of the earlier Roman examples, if not nec-

essarily retaining their content or function. Again

gold coinage dominated, especially the denomina-

tion of the tremissis, one-third of the solidus. Silver

and copper issues were rare and intermittent. Al-

though the earliest coins were of pure gold, like

their Roman predecessors, by

A.D. 600 debasements

effected by alloying silver with the gold can be

noted in many of the issues. The weight of the coin-

age also underwent reduction; by

A.D. 600 the stan-

dard of the solidus in Gaul had dropped from 24

karats of weight to 21 karats.

The first issues of the Germanic rulers also fol-

lowed the imperial example by placing the name

and image of the reigning emperor, by that time in

Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), on the ob-

verse of their gold coins. The rarer issues of silver

and copper coins sometimes had the name or

monogram of the issuing king. Shortly before the

middle of the sixth century the Frankish king

Fig. 1. Frisian gold tremissis of Dorestad. THE AMERICAN

NUMISMATIC SOCIETY, NEW YORK. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

Theodebert put his own name on his gold issues,

thereby provoking an angry response from the By-

zantine writer and historian Procopius, who assert-

ed that only emperors had the right to put their im-

ages on gold coins. By the end of the century kings

of the Suevi and the Visigoths also had replaced the

imperial name with their own on their gold coins.

Frisian and Anglo-Saxon gold tremisses were mod-

eled on those of Francia; the name of an English

king first appears on a coin in the first half of the sev-

enth century. The pseudo-imperial coinage lasted

longer in Italy, where the Ostrogothic issues were

replaced by those of the Byzantine reconquerors

and finally by the Langobards, who put their king’s

name on the coinage only at the end of the seventh

century. Most of these issues followed the Roman

and Byzantine imagery of a portrait obverse and a

symbolic reverse, with the cross becoming the most

common reverse image.

It is evident that a coinage comprising only gold

pieces, as was characteristic of most of Europe in the

fifth through seventh centuries, was ill suited to a re-

tail economy and would have been outside the daily

experience of most people. A great proliferation of

mints, especially in the Merovingian and Visigothic

kingdoms, implies a change in the circumstances of

minting from centralized to local, paralleling

changes in the bases of tax collection. This phenom-

COINAGE OF THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

ANCIENT EUROPE

357

Fig. 2. Silver sceatta. THE AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY, NEW YORK. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

enon is most apparent in the coinage of seventh-

century Francia, where the names of hundreds of

mint towns appear on the coins, along with names

of thousands of people identified as “moneyers.”

Finds of Byzantine gold coins and southern

Frankish ones in Frisia (a northern province in mod-

ern-day Netherlands) and England suggest a trade

route for goods imported from the north to the

Mediterranean. Finds of coins of the sixth and sev-

enth centuries are extremely rare beyond the

boundaries of the former Roman Empire, however;

the few tremisses found in western Jutland seem to

tie into the Frisian economic network rather than to

a Scandinavian or Baltic sphere.

THE AGE OF SILVER

In the course of the seventh century the gold coin-

ages of Merovingian Francia, of Frisia, and of

Anglo-Saxon England gave way to silver issues, and

silver remained virtually the only coin metal in

Transalpine Europe for the rest of the millennium.

In Spain the Visigoths continued to produce de-

based gold tremisses until Muslim invaders elimi-

nated their kingdom in

A.D. 711. The Langobard

kings maintained their gold coinages in Italy un-

til Charlemagne’s conquest at the end of the

eighth century, and the semi-independent Ben-

eventan dukes continued minting gold into the

ninth century.

In Francia silver coins moved gradually away

from the seventh-century type of portrait and cross

with the names of moneyer and mint. By the end of

the Merovingian dynasty in the mid–eighth century

most denarii were small chunks of silver with simple

geometric designs on both faces and few legible in-

scriptions. The silver coins of Frisia and England in

the period, known as sceattas, also were small, thick,

and lacking in legends; their imagery in some cases

appears to have derived from local artistic traditions

(fig. 2). A brief issue of sceattas minted at Ribe on

the west coast of Jutland c.

A.D. 720 can lay claim

to being the earliest European coinage minted be-

yond the ancient Roman borders.

In the second half of the eighth century silver

coinages underwent modifications in appearance

and weight standards that resulted in the coin

known as the penny (called the denarius in Latin,

the denier in French, and the pfenning in German).

These innovations appear to have been the initia-

tives of Carolingian kings, with Pepin the Short, the

first of the “mayors of the palace” to take the title

of king, standardizing the coinage shortly after be-

coming king of Francia in

A.D. 751 and his son

Charlemagne creating a new, heavier penny for his

enlarged realm in about

A.D. 793 (fig. 3). The coins

of the kingdoms that made up Anglo-Saxon En-

gland followed a similar pattern of reform and stan-

dardization.

By

A.D. 800 the silver penny was a broad, well-

struck coin weighing between 1.5 and 2.0 modern

grams. In England the coins usually featured a royal

portrait on the obverse, whereas the Carolingians

favored geometric types, especially the monogram

of the ruler’s name. Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

358

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 3. Silver penny of Charlemagne. THE AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY, NEW YORK. REPRODUCED BY

PERMISSION

.

coins bear the names of a substantial number of

mints throughout their respective realms, generally

coinciding with the main commercial and ecclesias-

tical centers. No such mints were located north or

west of the Roman boundaries of England or be-

yond the Rhine-Danube frontiers on the Conti-

nent.

The standardized silver pennies of the Carolin-

gian empire and of England provided a sound basis

for retail and long-distance commerce and facilitat-

ed the development of a monetized segment of the

economy to supplement the heavily subsistence and

manorial agricultural base. The uniformity of the

Carolingian coinage broke down with the dissolu-

tion of the centralized power of the empire. Counts

and dukes and even bishops and abbots took over

minting throughout the empire, although they

often retained a royal or imperial Carolingian name

on their coins. In the course of the tenth century

minting began east of the Rhine and north of the

Danube, chiefly at mints in Saxony exploiting the

newly discovered silver deposits there.

Almost no English or Carolingian coins of the

ninth century are found in Scandinavia that would

correspond to the well-documented booty seized

by Viking raiders and tributes exacted by them; if

such wealth reached the Baltic region in the form of

coins, these must have been melted rather than bur-

ied. A series of coins imitating those of Charle-

magne was minted in Jutland, probably at Hedeby

(Haithabu in German), in the early ninth century,

but local minting then ceased until about the year

1000.

Large Viking Age hoards are found in the lands

bordering the Volga basin, on the eastern shores of

the Baltic, and in Scandinavia, especially on the is-

land of Gotland. These comprise Islamic silver dir-

hams, chiefly of the tenth century; Byzantine silver

coins from the same period; and German and En-

glish pennies of the late tenth century and the elev-

enth century. As in the case of the earlier hoards of

Roman and Byzantine solidi, these silver finds of the

end of the millennium have been interpreted vari-

ously as the results of trade, booty, tribute, and the

pay of mercenary soldiers. The extent of the use and

recirculation of these coins in a local northern eco-

nomic sphere is difficult to ascertain.

By the end of the first millennium

A.D. coinage

had spread throughout Europe. The silver penny

was struck by royal authority in England and by

more localized rulers in France, Germany, and Italy.

Minting was initiated in Bohemia in the

A.D. 960s,

in Kiev in about

A.D. 990, and in Hungary and Po-

land shortly after 1000. In Scandinavia the Hedeby

coinage was revived after

A.D. 950, and by the year

1000 Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian kings had

initiated royal coinages. Not all of these initiatives

resulted in continuous minting, and it would not be

until the commercial revolution of the twelfth cen-

tury that Europe could be said to have a fully mone-

tized economy.

See also Coinage of Iron Age Europe (vol. 2, part 6).

COINAGE OF THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

ANCIENT EUROPE

359

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bellinger, Alfred R., and Philip Grierson. Catalogue of the

Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and

in the Whittemore Collection. 5 vols. Washington, D.C.:

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection,

1966–1973. (The standard reference work for Byzan-

tine coins. Three volumes pertain to the early Middle

Ages: Vol. 1, Anastasius I to Maurice,

A.D. 491–602;

Vol. 2, Phocas to Theodosius,

A.D. 602–717; Vol. 3, Leo

III to Nicephorus III,

A.D. 717–1081.)

Blackburn, Mark, and D. M. Metcalf, eds. Viking-Age Coin-

age in the Northern Lands. 2 vols. BAR International

Series, no. 122. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports,

1981. (A collection of articles surveying the importa-

tion of coinage into the Scandinavian and Baltic world

at the end of the first millennium.)

Grierson, Philip, and Mark Blackburn. Medieval European

Coinage. Vol. 1, The Early Middle Ages (5th–10th Cen-

turies). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press,

1986. (The definitive study of all coinages minted in

Europe in the period, with discussion and bibliography

summarizing all the important literature to its date of

publication.)

Gierson, Philip, and Melinda Mays. Catalogue of Late

Roman Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and the

Whittemore Collection. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton

Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992.

Hendy, Michael. “From Public to Private: The Western Bar-

barian Coinages as a Mirror of the Disintegration of

Late Roman State Structures.” Viator 19 (1988): 29–

78.

McCormick, Michael. Origins of the European Economy:

Communications and Commerce,

AD 300–900. Cam-

bridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2002. (Uses

the evidence of the importation of Byzantine and Islam-

ic coins into Europe to argue for the importance of

commerce in the Carolingian economy.)

Metcalf, D. M. “Viking-Age Numismatics.” Numismatic

Chronicle 155 (1995): 413–441; 156 (1996): 399–

428; 157 (1997): 295–335; 158 (1998): 345–371; 159

(1999): 395–430. (A series of articles examining coin-

age in the North Sea and the Baltic region from late

Roman times to the end of the first millennium.)

Spufford, Peter. Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe.

Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

(A thorough discussion of the role of coinage in the Eu-

ropean economy from the end of the Roman period

through the later Middle Ages.)

A

LAN M. STAHL

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

360

ANCIENT EUROPE