Boggs S. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

16.4 Kinds of Sedimenta Basins

557

Basins in Divergent Settings

Divergent tectonic settings are regions of Earth where tectonic plates are separat

ing. These regions are characterized by extensional (stretching) features. Examples

of extension include seafloor spreading along mid-ocean ridges and the stretching

and downfaulting of continental crust to form grabens. Basins form in divergent

settings owing to crustal thinning as well as to sedimentary and volcanic loading

and crustal densification (Fig. 16.2).

The early stages of rifting are characterized by breaking of the crust and

down dropping of blocks to form fault grabens called terrestrial rift valle

y

s. Rifts

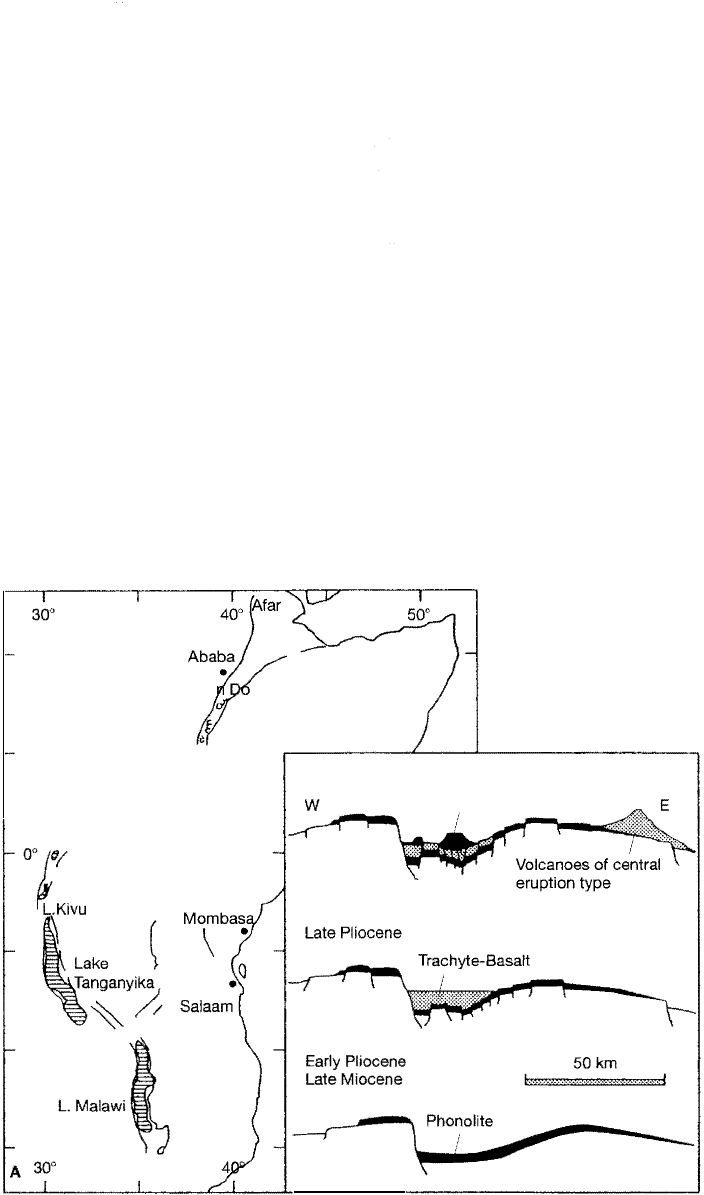

(Fig. 16.3A) are narrow, fault-bounded valleys that range in size from grabens a

few kilometers wide to gigantic rifts such as the East African Rift System, which is

nearly 3000 km long and 300 km wide. Rifts result from a thermal event of some

kind that causes extension or spreading within continental crust. The East African

Rift System (Fig. 16. 4A) is an example of a young rift zone. Different stages in the

development of the rift are illustrated in Figure 16.4B. The East African Rift is

filled mainly with volcanic rocks; however, a great variety of sedimentary envi

ronments can exist within rifts, ranging from nonmarine (fluvial, lacustrine,

desert) to marginal marine (delta, estuarine, tidal flat) and marine (shelf, subma

rine fan). Thus, the deposits of rift basins can include conglomerates, sandstones,

shales, turbidites, coals, evaporites, and carbonates. Many ancient rift systems are

known from Asia, Europe, Africa, Arabia, Australia, North America, and South

America (e.g., Sengor, 1995; Leeder, 1995; Ravs and Steel, 1998). They occur

many tectonic settings (Sengor, 1995) but are particularly common in divergent

settings.

As opening of an ocean proceeds, continued extension within continental

crust leads to additional thinning of the crust and eventually rupturing, allowg

basaltic magma to rise into the axis of the rift and begin the process of forming

10° Addis

Ab�

a

E

thiopia me

(

I

�

_ \ L. Tu rkana Quaternar

y

.Mobutu

Caldera Volcano

L.

E

dward

Ken

y

�

Dome

o

o

i

l o-·

o

o

• Nairobi

.

) }

L

�

Kivu

L.Victoria 1

l.J ro..�

�

��

Salaam

100

•

/

L. Malawi

�

B

Figure 16.4

Map (A) showing the surface

configuration of the East

African Rift Zone and cross

sections (B) illustrating

stages in evolution of the rift

from late Miocene through

the Quaternary. The rift is

floored by volcanic rocks

and volcaniclastic detritus.

[From Einsele, G., 1992,

Sedimentary basins, Fig.

12.4, p. 434. Reprinted by

permission of Springer-Ver

lag, Berlin.]

558

Chapter 16 1 Basin Anahsis, Tectonics, and Sedlm�nlation

AFRJCA

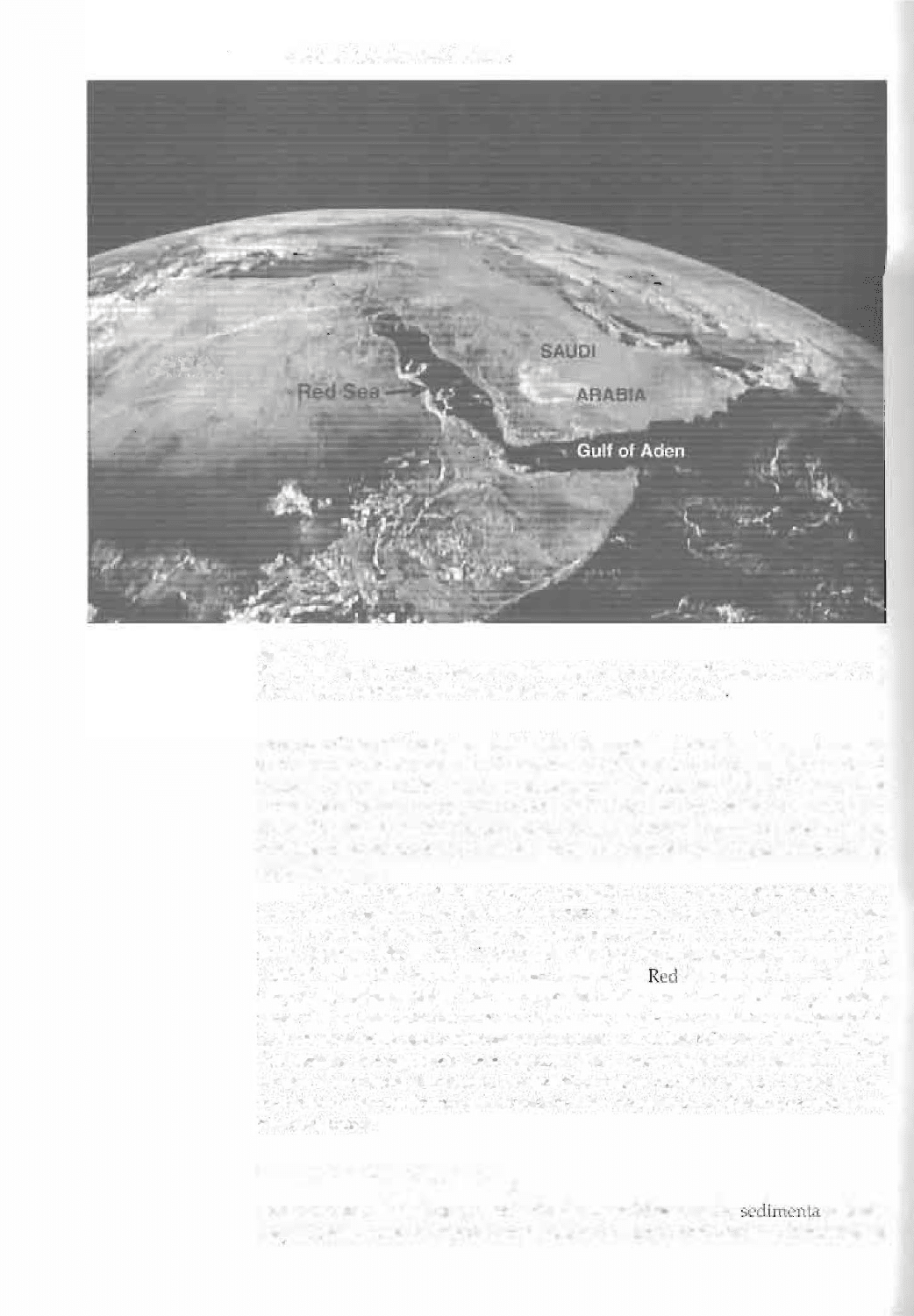

Figu 16.5

V

1

e\•1 or the Red Sea,

l

ying between northeJstem .frica and Sauo1 Arbia, from Apollo 17

illfCtfL NASA phvtograph, download�d from the Internet 6/26/04

nev O�JnlC Cm�t. H1.S, krrestrial rift Valleys gr.�dua!Jy (' VOIVe intn protO·Ocean

jc rift oughs. rruto-oceanic rift are omed ( t least Ln part) b�· ucean ic crust and

ked by �i oung rifled continent�! mq;tns. Tite Red Se [Fig. 1o.3) is the t

modrn nlog of a proto-oceanic rift. Tbe l� . Sea, whJ, li beeen northeast

ern AfnL and Saudi Arabia, is 21)00 km long, is more lh 200 km wide in plac,

and has 0 x1l zone about 50 km v,·ide with some axial deFp" that extend �o

more th.n 3 km.

The axial region i oored by

y

oun

b

m._y.) ocw1ic cru,t in lhf� LJUthern

third of the Red a. The shelv� of the se,, ar underlain by stretched continental

ernst in cenLTal reas but by an abrupt ocet-conti.nental crust tTonsitic)n in the

orth ( L�e�h�t� J 999, p. 511 ). 1 o th� ��xLth, the Red Se inter�ts the slow-spreildig

CL1lf ot Adt>n dft. The extension that formed the R

e

d

started in middle Ter

tiary. Early sedimenl,1tion that accompcd rifting was c1ractedzed b\- de1p

munt of ma rginal alluvial fans and ian del t.ls, ns weH as near�hore sedimentatinn

rn both ilrckh1stic nd CMbouk environnlcnts. During rv1 wcce lime, significilnl

�hickncss � of \'apnrites were dep('l ited as rc.�11Jl of periodic io!a!ion of the

trough. Conditions rt•tued to norml li.niLie� f'l iOCl'ne tl�. Bolone S

rncntdiJnn was pa . lr!y chardctt•riLcd by dcpusltinn of fam-pp( ld �cal

�ttou�) ooz.

Basins in Intraplate Settin

Onu t oe b.u has opene,J fully dung d Wilson cycle,

e

dim

nl

.

.ry bins

mov e �·rH in a ariety o( Hlngs along the �ngin and wHhin bo�h ontinental

16.4 Kinds of Sedimenta Basins

559

and oceanic plates. Continental margins formed during opening of an ocean are

called passive margins (lacking significant seismic activity). Continental crust is

commonly thinned on passive margins and a zone of transitional crust is present

between fully continental crust and fully oceanic crust (Fig. 16.3B). Thus, sedi-

ments may be deposited settings floored by wholly continental crust, transi-

tional crust, or wholly oceanic crust.

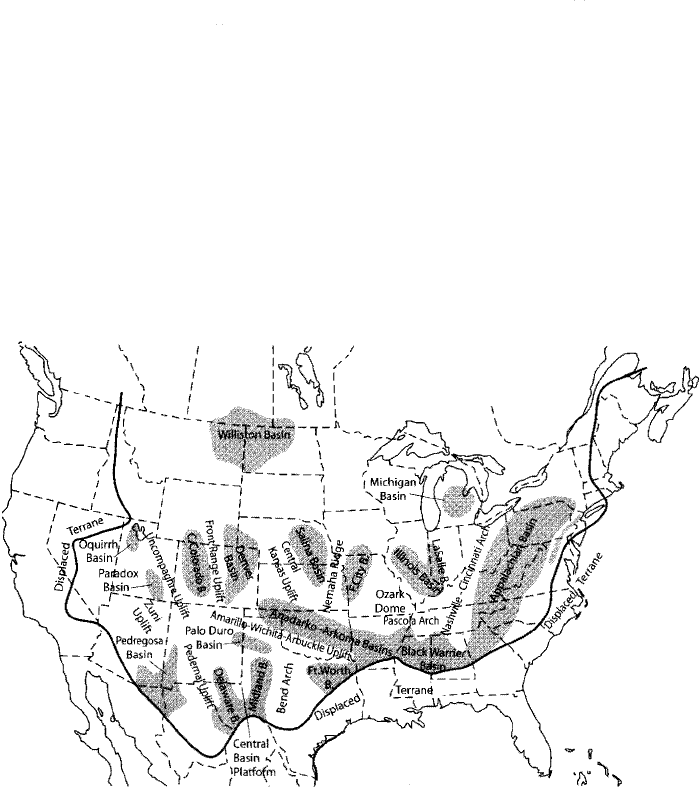

Intraplate Basins Formed on Continental - Transitional Crust

Continental platforms are stable cratons covered by thin, laterally extensive sedi

mentary strata. Basins developed on these stable platforms are referred to as cra

tonic basins. They are commonly bowl shaped (ovate), and they are generally

filled with Paleozoic and Mesozoic sediments that formed under shallow-water

conditions. Sediments can include shallow marine sandstones, limestones, and

shales, as well as deltaic and uvial sediments. The sediments commonly thicken

toward the basin centers where they may attain thicknesses of 1000 m or more.

The North American craton is an example of a major continental platform marked

by numerous cratonic basins (Fig. 16.6). These basins filled with sediment ranging

in age from Paleozoic to Mesozoic (Sloss, 1982).

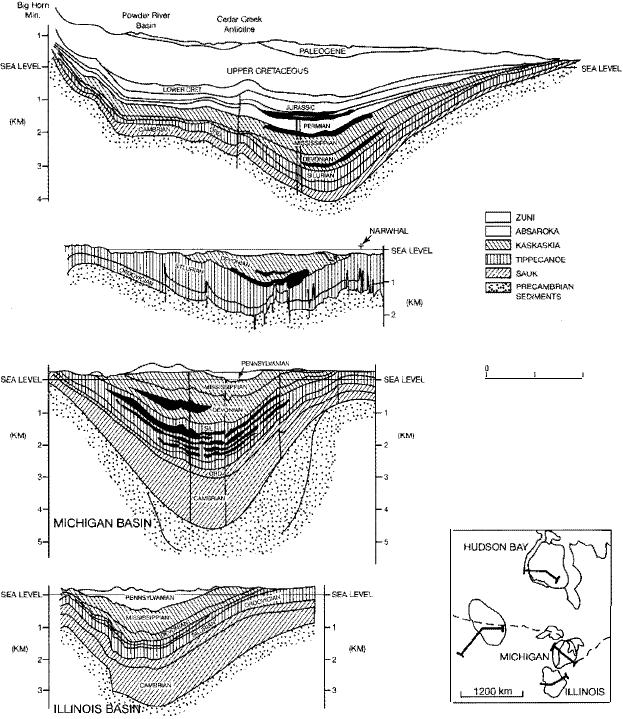

Several different kinds of basins may form in cratonic settings. Intracratonic

basins (Fig. 16.3C) are broad basins floored by fossil rifts in axial zones. They are

relatively large, commonly ovate downwarps at occur within continental interi

ors away from plate margins. Subsidence in inacratonic basins may be due largely

to mantle-lithosphere thickening and sedimentary or volcanic loading (Fig. 16.2),

however, several other causes have also been proposed, such as crustal thinning

(e.g., Klein, 1995). e presence of fossil rifts beneath intracratonic basins, such as

the Michigan Basin, suggests some crustal thinning and possibly crustal densifica

tion. Some intercraton basins are filled with marine siliciclastic, carbonate, or

evaporite sediment deposited from epicontinental seas; others contain nonmarine

sediments. Ancient North American intracratonic basins include the Hudson Bay

Basin (Canada), Michigan Basin, Illinois Basin, and Williston Basin (Fig. 16.6,

16.7). Ancient inacratonic basins on other continents include the Amadeus Basin

of Australia; the Parana Basin in southe Brazil, Paraguay, northeast Argentina,

and Uruguay; the Paris Basin in France; and the Carpentaria Basin in Australia

�

\

\

Figure 16.6

Late Mississippian-Early juras

sic cratonic basins on the

North American (mainly USA)

craton. The Michigan, Illinois,

and Williston Basins are in

tractatonic basins. [After

Sloss, 1982, The Midconti

nent provinces: United States,

in Palmer, A. R. (ed.), Perspec

tives in regional geological

synthesis: D-NAG Special

Publ. 1, Geological Society of

America, Fig. 3, p. 36. Repro

duced by permission.]

560

Chapter 16 I Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentation

Fire 16.7

w

WILLISTON BASIN

SEALELr,

IK"l

: HUDSON

BAY

Nesn

!ne

-T

� CRYSTALLINE

PRECAlBR1AN

E

1

2km

Schematic cross section of four in

tracratonic basins in North America.

The locations of the cross sections are

shown in the inset map. The terms

Zuni, Absaroka, Kaskaskia, Tippecanoe,

and Sauk refer to depositional se

quences identified on the craton (Sloss,

1982). [From Leighton and Kolata,

1990, Selected interior cratonic basins

and their place in the scheme of global

tectonics, in Leighton, M. W., et al.

(eds.), Interior cratonic basins: MPG

Memoir 51, Fig 35.9, p. 743. Repro

duced by permission.]

WILLISTON

-�---w

�ICHIGANr/

1 1200 km 1 BLLINOIS

(Klein, 1995; Leighton et al., 1990). The Chad Basin in Africa is an example of a

modern intracratonic basin.

Not all basins that form on cratons are intracratonic basins, as defined in

Table 16.2. Some of the North American basins shown in Figure 16.6, for example,

formed by mechanisms other than rifting. The Paradox basin formed by strike-slip

(compressional) processes. Several other basins (e.g., Oquirrh, Denver, Appalachi

an) are foreland basins, whose origins are related to collisional (compressional)

events (G. D. Klein, personal communication, 2004). The Anadarko Basin may be

an aulacogen. [These various kinds of basins are discussed subsequently.]

Continental rises and teaces are features characterized by enormous wedges

of sediment botmded on the seaward side by the gently sloping continental slope

and rise. A structural discontinuity is psent beneath e terrace-rise system be

tween normal continental crust and modified or transional crust (Fig. 16.3B). These

rises and terraces are the consequence of continental rifting within passive margins

initiated along divergent plate boundaries (Bond, Kominz, and Sheridan, 1995).

Sediments accumulate in several parts of e terrace-rise system-shelf, slope, and

contental rise at the foot of the slope. Sediments deposited in this setting can in

dude shallow neritic sands, muds, carbonates, and evaporites on the shelf;

hemipelagic muds on the slope; and turbidites on continental rises. Thick prisms of

sediment may accumulate owing to long-continued subsidence, which may. be

caused by deep crustal metamorphism (causg increase in density of lower crustal

rocks), crustal stretching and thinning, and sediment loading.

16.4 Kinds of Sedimenta Basins

561

Sedimentation on continental terraces and rises occurs after continental rift

ing is completed and a new basin has begun to form by seafloor spreading (Bond,

Kominz, and Sheridan, 1995). The basin is locked into a relatively stable interplate

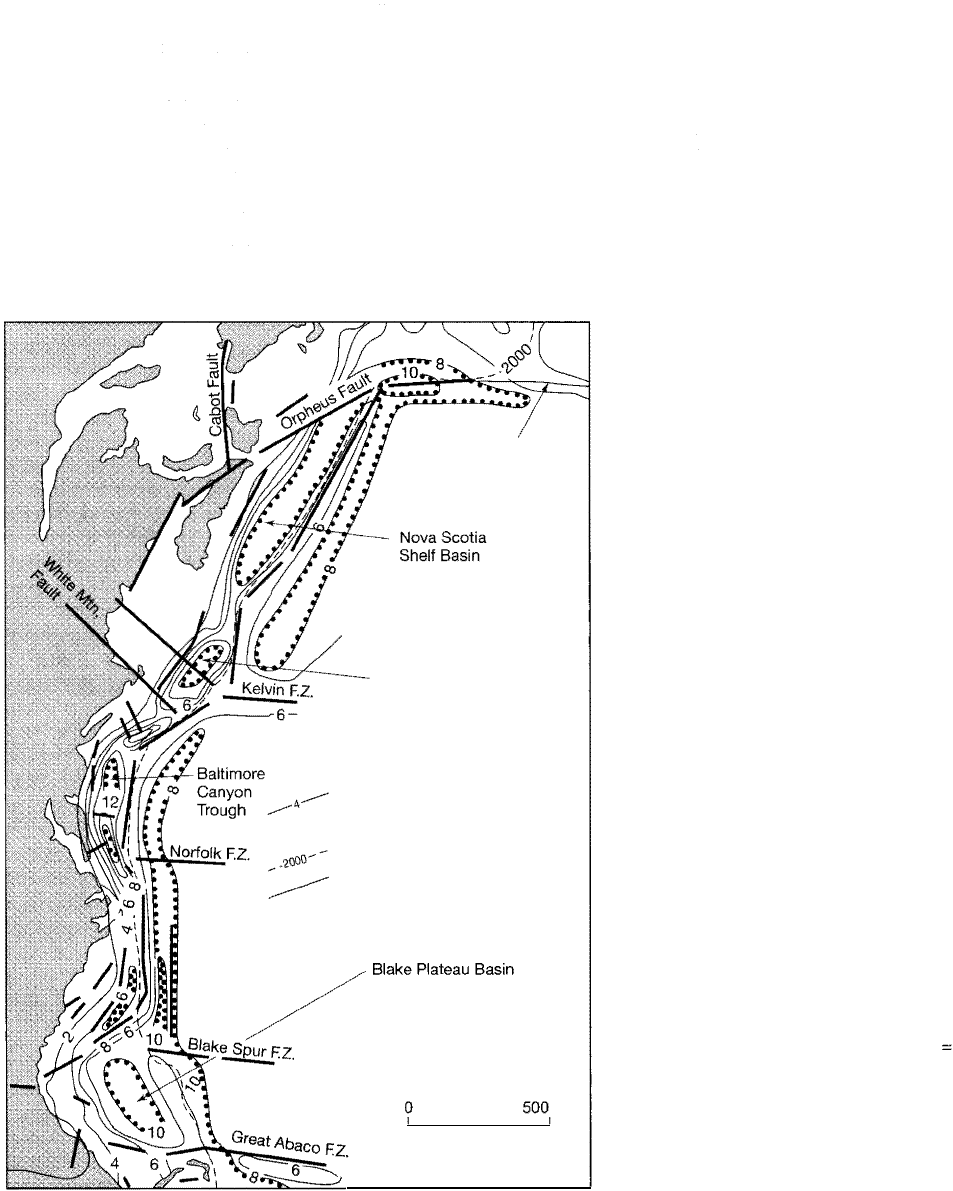

position at the edge of the rifted continent. Good examples of such basins are the

basins located o the eastern United States and the southeastern Canada coast

(Blake Plateau Basin, Carolina Trough, Baltimore Canyon Trough, Georges Bank

Basin, Nova Scotian Basin; Figure 16.8) which were created in late Triassic to early

Jurassic time by rifting accompanying the breakup of Pangaea (Manspeizer, 1988).

Some of these basins were isolated from the sea and accumulated thick deposits of

arkosic

clastic sediments and lacustrine deposits, intercalated with basic volcanic

rocks. Others, with some connections to the sea, accumulated deposits ranging

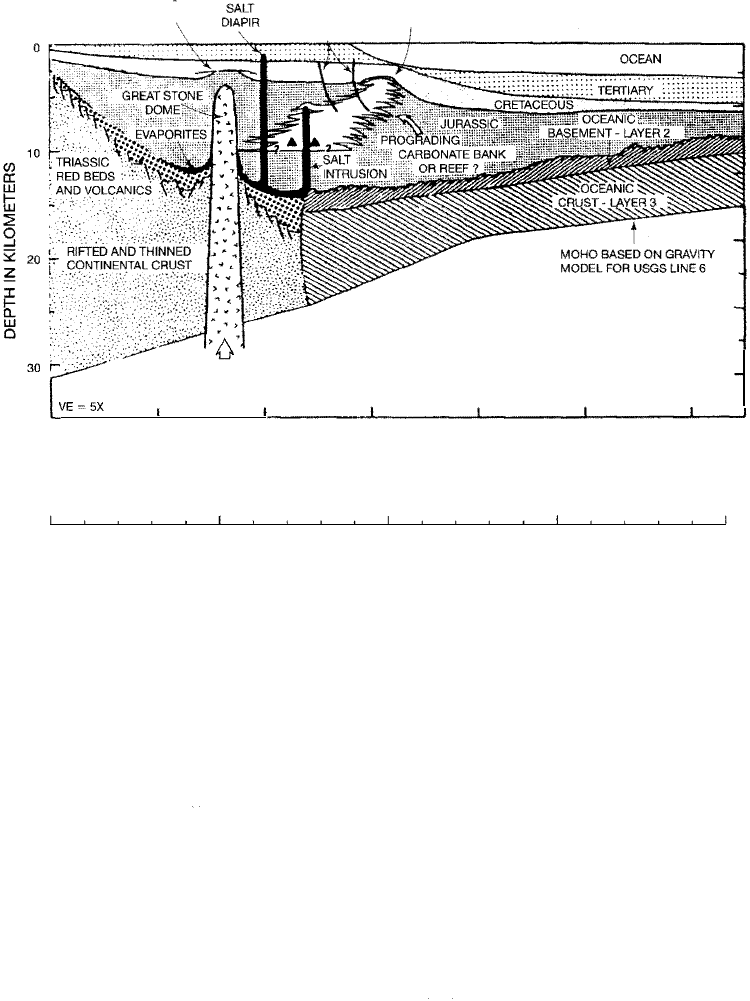

from evaporites to deltaic sediments, turbidites, and black shales. Figure 16.9

shows some of the sediments in the Baltimore Canyon Trough. Other examples of

terrace-slope basins include the Campos Basin, Brazil; the northwest shelf of Aus

tralia; and the sedimentary basins of Gabon on the west coast of Africa (Edwards

and Santogrossi, 1990). Some terrace-slope basins are prolific producers of petrole

um and natural gas.

Newfoundland

Ridge Z.

George's Bank Basin

Depth to pre-Jurassic

basement i

n k

i

lometers

(contour

i

nterval = 2 km)

�

oo

�

-

2000-m isobath

_

.v

Continental margin fault

6

km

Figure 16.8

Sedimentary basins on the passive continen

t

al margin of eastern North America. F.Z.

fracture zone. [After Sheridan, R. E., 1974,

Atlantic continental margin of North Ameri

ca, in Burk, C. A., and C. L. Drake (eds.),

The geology of continental margins, Fig.

12, p. 403. Reprinted by permission of

Springer-Verlag, New York.]

562

Chapter 16 I Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentation

ALB. APT.

UNCON

JURASSIC

EARLY CRETACEOUS

GROWTH

SHELF EDGE

FAULTS

0

�������

0

0

0

LOWER CRETACEOUS

VOLCANIC INTRUSION

100

50

Figure 16.9

MTLE

200

KILOMETERS

100

MILES

20

w

40

0

�

z

�

0

�

80

w

a

100

300

150

200

Interpretative stratigraphic section across the Atlantic continental margin of North Ameri

ca in the vicinity of Baltimore Canyon Trough_ Based on geophysical data and drill-hole in

formation_ [After Grow, ). A., 1981, Structure of the Atlantic margin of the United States,

in Geology of passive continental margins: Am. Assoc. Petroleum Geologists Ed_ Course

Note Ser. No. 19, Fig. 13, p. 3-20. Reprinted by permission of MPG, Tulsa, Okla.]

Intraplate Basins Floored by Oceanic Crust

These oceanic basins (e.g., Fig. 16.30) occur in various parts of the deep ocean

floor. They are created by rifting and subsidence accompanying opening of an

ocean owing to continental rifting. Oceanic basins may include ocean-floor sag

basins as well as fault-bounded basins associated with ridge systems. Sedimen

that accumulate in these basins are mainly pelagic clays, biogenic oozes, and tur

bidites. Sediments deposited in oceanic basins adjacent to active margins may

eventually be subducted into a tnch and consumed during an episode of ocean

closing. Alteatively, they may be offscraped in trenches during subduction to

become part of a subduction (accretionary) complex (Fig. 16.3E). e Pacific

Ocean is a modern example of a major active ocean basin. The Gulf of Mexico is a

modem example of a dormant ocean basin, which is floored by oceanic crust that

is neither spreading nor subducting.

Bas

i

ns

i

n Convergent Sett

i

ngs

Subduction-Related Basins

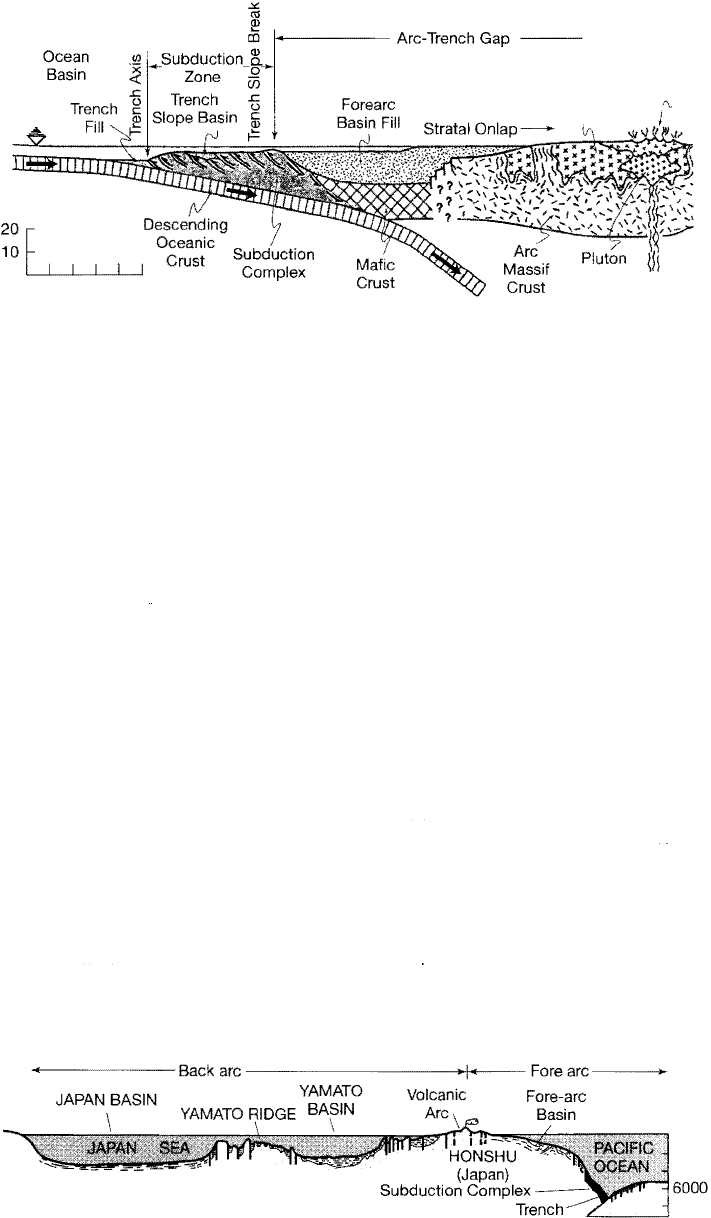

Subduction-related settings (Fig. 16.3E) are features of seismically active continen

tal margins, such as the modern Pacic Ocean margin. These settings are charac

terized by a deep-sea trench, an active ·volcanic arc, and an arc-trench gap

separating the two. The most important depositional sites in subduction-related

settings are deep-sea trenches, fore-arc basins that lie within e arc-trench gap

16.4 Kinds of Sedimenta Basins

563

��

I

H = v

0

[

I I I I I

10 20 30 40 50

Scale in km

--··J�

.

� Volcantc

E Chain

E

roded �, 1

P

luton

Arc

Magmatism

(Fig. 16.10), and back-arc, or marginal, basins that lie behind the volcanic arc in

some arc-trench systems (Underwood and Moore, 1995; Dickinson, 1995; Marsaglia,

1995). Subduction-related settings may occur also along a contental-margin arc

(not shown in Fig. 16.3) rather than an oceanic arc. In these continental-marg set

tings, so-called retro-arc basins (intermontane basins within an arc orogen) may

lie on continental crust behind fold-thrust belts (e.g., Jordan, 1995). Sediments de

posited in subduction-related basins are mainly siliciclastic deposits derived

largely from volcanic sources in the volcanic arc. These deposits include sands and

muds deposited on the shelf and muds and turbidites deposited in deeper water

in slope, basin, and trench settings. Sediments in the trench may include terrige··

nous deposits transported by turbidity currents from land, together with sedi

ments scraped from a subducting oceanic plate, which together form an

accretionary complex (Fig. 16.3E; Fig. 16.10). The most characteristic kind of rock

in an accretionary wedge is melange, a chaotically mixed assemblage of rock con

sisting of brecciated blocks in a highly sheared matrix.

Examples of modern trench and fore-arc sedimentation sites include the

Sondra, Japan (Fig. 16.), Aleutian, Middle America, and Peru-Chili arc-trench

systems (Leggett, 1982; Dickinson, 1995; Underwood and Moore, 1995). Examples

of ancient fore-arc basins include the Great Va lley fore-arc basin, California; Ore

gon Coast Range; Tamworth Trough, Australia; Midland Valley, Great Britain; and

Coastal Range, Taiwan (Dickinson, 1995; Ingersoll, 1982). The Japan Sea is a good

mode example of a back-arc basin (Fig. 16.11); the Late Jurassic-Early Creta

ceous basin formed behind the Andean arc in southernmost Chile is a well-stud

ied example of an ancient back-arc basin (Marsaglia, 1995). The Taranaka Basin,

New Zealand, and the Magdalena Basin, Columbia, both petroleum producers,

are additional examples of active-margin basins (Biddle, 1991). For further insight

into subduction-related settings, see Busby and Ingersoll (1995).

Figure 16.11

Om

2000

4000

__ ,.·�

-

6000

_

__

8000

Schematic representation of an active continental margin (Japan), showing both the fore

arc and back-arc characteristics of the margin. [From Boggs, S., Jr., 1984, Quaternary sedi

mentation in the japan arc-trench system: Geol. Soc. America Bull., v. 95, Fig. 2, p. 670.]

Figure 16.10

Schematic representation

of basin structure in the

trench and fore-arc zone of

a subduction setting. [After

Dickinson, R., 1995,

Forearc basins, in Busby, C.,

and R. V. Ingersoll (eds.),

Tectonics of sedimentary

basins: Blackwell Science,

Cambridge, Mass., Fig. 6.1,

p. 221 .]

564

Chapter 16 I Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentation

Figure 16.12

Basins in Collision-Related Settings

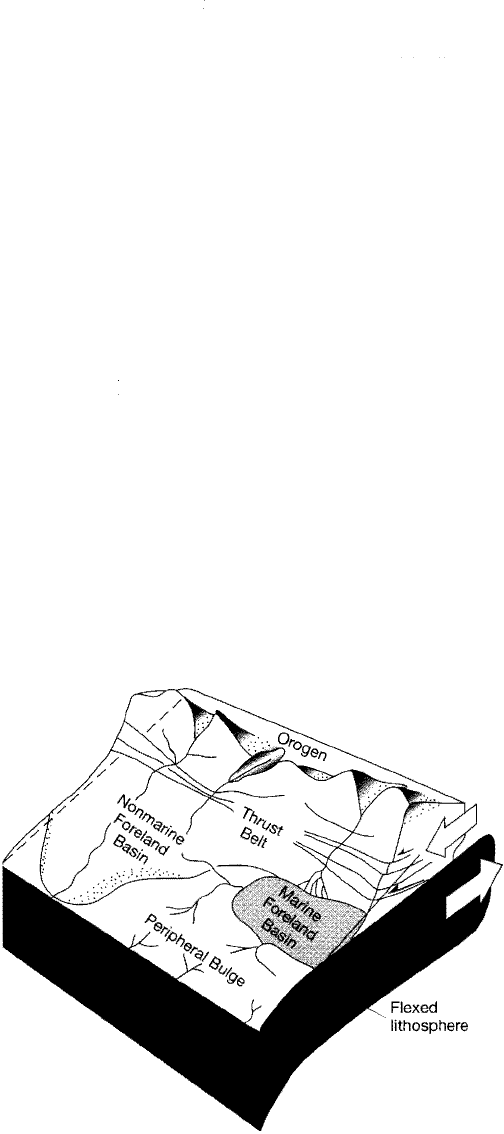

Collision-related basins are formed as a result of closing of an ocean basin and

consequent collision between continents or active arc systems, or both. Figure 16.3F

illustrates some of the basins that may be generated as a result of plate collision.

For example, collision can generate compressional forces, resulting in develop

ment of fold-thrust belts and associated peripheral foreland basins along the col

lision suture belt where rifted continental margins have been pulled into

subduction zones. Figure 16.12 illustrates the ndamental elements of a foreland

basin system. Foreland basins may be isolated from the ocean and receive only

nonmarine gravels, sands, and muds, or they may have an oceanic connection and

contain carbonates, evaporites, and/ or turbidites. Examples of foreland basins in

clude those of western Taiwan, the Alpennines, and eastern Pyrenees; the Magal

lanes Basin at the southern tip of South America; basins of the northwestern

Himalayas; and various basins in the Appalachians, Rocky Mountains, and west

ern Canada (Allen and Homewood, 1986; Macqueen and Leckie, 1992; Dombek

and Ross, 1995).

Because of the irregular shapes of continents and island arcs, and the fact that

landmasses tend to approach each other obliquely during collision, portions of

old ocean basin may remain unclosed after collision occurs. These surviving em

bayments are called remnant basins. Mode remnant basins include the Mediter

ranean Sea, Gulf of Oman, and northeast South China Sea. The Marathon Basin,

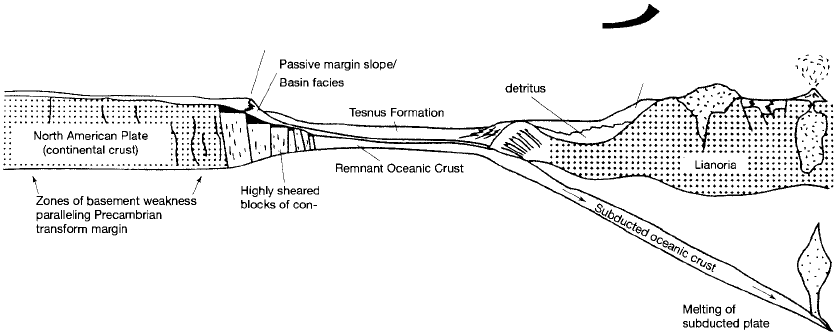

Texas, provides an example of Pennsylvanian-age sedimentation in an ancient rem

nant basin adjacent to a fore-arc basin (Fig. 16.13). Structural weaknesses devel

oped in this region in the late Precambrian/ early Cambrian and were reactivated

in the late Paleozoic as reverse faults in response to compressional stresses (Wuell

ner, Lehtonen, and James, 1986). An early phase of sedimentation filled part of the

fore-arc basin with volcaniclastic detritus. Subsequently, sediments of the Te snus

Formation accumulated in the fore-arc and remnant basin. Later deposition of the

Dimple Limestone and Haymond Formation (not shown in Fig. 16.13) generated a

total of more than 3400 m of Pennsylvanian sediment in the basin. Sediments in

clude sandstones, shales, and limestones deposited in environments ranging from

shelf/platform to submarine fan (turbidite) settings. Other ancient examples of

remnant basins include the southern Uplands of Scotland (Silurian-Devonian);

Nevadan orogenic belt, Califoia Uurassic); weste Iran (Cretaceous-Paleogene);

Schematic illustration of the fundamental elements of

an orogen-foreland-basin system: a compressional

orogen and thrust belt and the foreland basin in

which erosion, sediment transportation, and deposi

tion take place. The basin may be filled to different

degrees along the strike zone depending upon the

relative rates of mass flux into the orogen, denudation

and sedimentation by surface processes, isostatic

compensation, and eustatic changes in sea level.

[After johnson, D. D., and C. Beaumont, 1995, Pre

liminary results from a planform kinematic model of

orogen evolution, surface processes and the develop

ment of clastic foreland basin stratigraphy, in

Dorobek, S.

L

., and G. M. Ross (eds.), Stratigraphic

evolution of foreland basins: SEPM Spec. Publ. 52,

Fig. 1, p. 4. Reproduced by permission.]

16.4 Kinds of Sedimenta Basins

565

N

Rapid sub�idence

of basin

Forearc basin

trap for early

volcanic detritus

� Predominant sediment influx

Position of early

arc-current position

of exhumed plutons

and metamorphic

terrane

Position of

volcanic arc

Dissected foreland facies

Shelfbreak

Early

volcanic

Met. +Piut.

detritus

Intra-arc

sediment

trap

Tobosa Basin

tinental crust

-Zone of crustal attenuation-

Figure 16.1 3

Cross-sectional diagram showing the remnant basin and associated basins that existed in

the Marathon Basin, Texas, during deposition of Carboniferous sedimentary rocks. [From

Wuellner, E. E., L. R. Lehtonen, and C. james, 1986, Sedimentary tectonic development

of the Marathon and Va l Verde basins, West Texas, U.S.A.: A Permo-Carboniferous migrat

ing foredeep, in Allen, P. A., and P. Homewood (eds.), Foreland basins: lnternat. Assoc.

Sedimentologists Spec. Pub. 8, Fig. 5, p. 354. Reproduced by permission of Blackwell Sci

entific Publications, Oxford.]

and the northeast Caribbean (Tertiary). These basins, and other examples, are dis

cussed by Ingersoll, Graham, and Dickinson (1995).

Basins in Strike-Slip/ansform-Fault-Related Settings

Strike-slip-related basins occur along ocean spreading ridges, along the transform

boundaries between some major crustal plates, on continental margins, and with

in continents on continental crust. Movement along strike-slip faults can produce

a variety of pull-apart basins, only one kind of which is illustrated in Figure 16.3G.

Faults that define strike-slip basins may be either "transform faults" that define

plate boundaries and penetrate the crust or "transcurrent faults," which are re

stricted to intraplate settings and penetrate only the upper crust (Sylvester, 1988).

Most basins formed by strike-slip faulting are small, a few tens of kilometers

across, although some may be as wide as 50 km (Nilsen and Sylvester, 1995). They

may show evidence of significant local syndepositional relief, such as the presence

of fault-flank conglomerate wedges. Because strike-slip basins occur in a variety

of settings, they may be filled with either marine or nonmarine sediments, de

pending upon the setting. Sediments in many of these basins tend to be quite

thick, because of high sedimentation rates that result from rapid stripping of ad

jacent elevated highlands, and may be marked by numerous localized facies

changes.

As shown in Table 16.2, basins in transform settings are referred to as

transtensional, transpressional, or transrotational depending upon whether the

basins formed by extension, compression, or rotation of crustal blocks along a

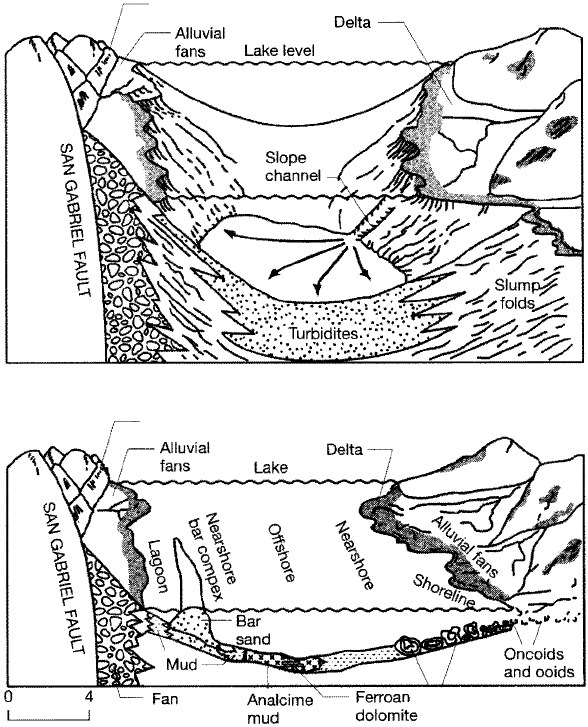

strike-slip fault system. The Ridge Basin, California (Fig. 16.14), is a good example

of an ancient transpressional basin. Strike-slip movement on the San Gabriel fault

in Pliocene/Miocene time created a lake basin about 15 km by 40 km in which up

s

566

Chapter 16/ Basin Analysis, Tectonics, and Sedimentation

West

Fault scarp

East

A Ope

n

lake basin

West

Fault scarp

E

ast

Figure 16.14

Paleoenvironmental reconstruction of the

Pliocene/Miocene Ridge Basin, California,

during (A) the open, deep-water lacustrine

and/or marine phase and (B) the closed,

shallow-water lacustrine phase. [After Link,

M. H., and R. H. Osborne, 1978, Lacustrine

facies in the Pliocene Ridge Basin Group,

Ridge Basin, California, in Matter, A., and

M. E. Tu cker (eds.), Modern and ancient

lake sediments: Blackwell Scientific Publica

tions, Oxford, Fig. 14, p. 185, and Fig. 15,

p. 186, reproduced by permission.]

km

breccias

Stromatolites

B Closed lake basi

n

to 9000 m of sediment eventually accumulated (Link and Osboe, 1978). Initiay,

the lake basin was open (Fig. 16.14A), allowg deltaic sediments and turbidites to

form. As a result of subsequent strike-slip displacement on the fault, exteal

drainage was blocked to the south and the lake basin became a closed system.

During the closed phase, alluvial fan, uvial, deltaic, and barrier-bar sediments

accumulated along the margins of the lake, and siliciclastic mud, zeolite mud,

dolomite, and stromatolites formed the cenal part of the basin (Fig. 16.14B).

For additional examples of strike-slip basins, see Nilsen and Sylvester, 1995.

Basins in Hybrid Seings

Aulacogens are special kinds of rifts situated at high angles to continental mar

gins, which are commonly presumed to be rifts at failed but were reactivated

during convergent tectonics (Fig. 16.3H). Other suggested origins for alaucogens in

clude doming and rifting, sike-slip-related extension, and continental rotaon

(Sengor, 1995). The long, narrow troughs that make up the arms of aulacogens ex

tend into continental cratons at a high angle from fold belts. Deposition of thick se

quences of sedent can take place in these arms during long periods of me. These

deposits may include nonmarine (e.g., alluvial-fan) sediments, marine shelf de

posits, and deeper water facies such as turbidites. Examples of aulacogens include