Boggs S. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

U. S. S. R.

Turkey

16.5 Sedimenta Basin Fill

567

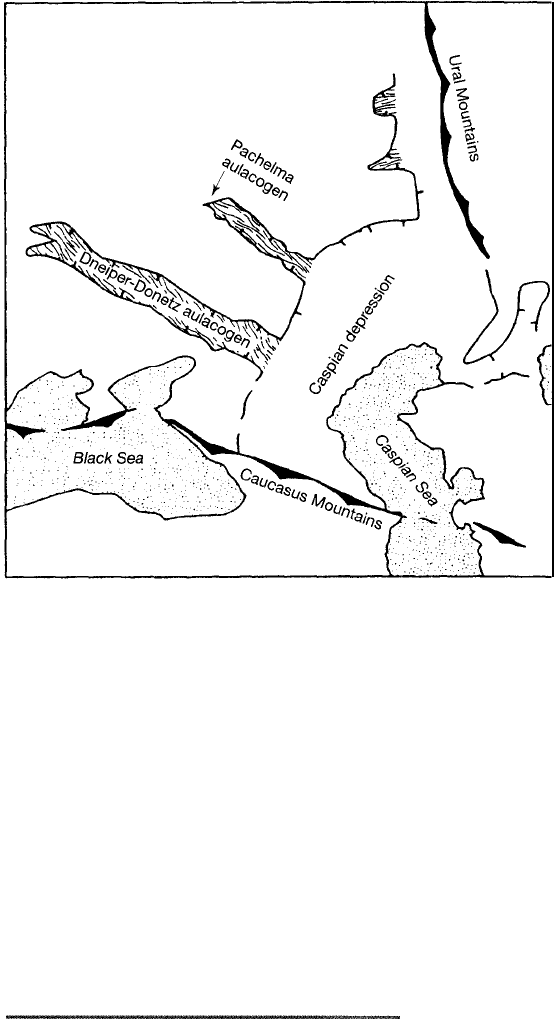

Figure 16.1 5

Aulacogen north of the Black and Caspian Seas

on the Russian platform. [After Burke, K., 1977,

Aulacogens and continental breakup: Annual Re

view of Earth and Planetary Sciences, v. 5. Re

produced by permission of Annual Reviews, Inc.]

the Reelfoot Rift of late Paleozoic age in which the Mississippi River flows, the

Amazon Rift in which the Amazon River flows, the Benue Tr ough of Cretaceous

age in which the Niger River is located, the aulacogen north of the Black and

Caspian Seas on the Russian platform (Fig. 16.15), and the Anadarko Basin in Ok

lahoma (Fig. 16.6). lmpactogens are structures similar to aulacogens in that they

formed at high angles to orogenic belts; however, they do not have a preorogenic

history.

Intracontinental wrench basins are hybrid basins that formed within conti

nental crust owing to distant collisional processes (e.g., the Quaidam Basin of

China). Successor basins are basins that formed in intermountain settings follow

ing cessation of local orogenic activity (e.g., the southern Basin and Range, Ari

zona). See Ingersoll and Busby (1995) and Sengor (1995) for details.

16.5 SEDIMENTARY BASIN FILL

The preceding discussion focuses on the structural characteristics of sedimentary

basins and the tectonic processes that create these basins. The particular concern

of basin analysis is, however, the sediments that fill the basins. This concern en

compasses the processes that produce the filling, the characteristics of the result

ing sediments and sedimentary rocks, and the genetic and economic significance

of these rocks. The fundamental processes that generate sediments (weathering/

erosion) and bring about their transport and deposition; the physical, chemical,

and biological properties of these rocks; the depositional environments in

which they form; and their stratigraphic significance are discussed in preceding

chapters of this book. The factors that control or affect these depositional

processes and sediment characteristics, discussed also in appropriate parts of

the book, include

568

Chapter 16 I Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentation

1. The lithology of the parent rocks (e.g., granite, metamorphic rocks) present in

the sediment source area, which controls the composition of sediment derived

from these rocks

2. The relief, slope, and climate of the source area, which control the rate of sed

iment denudation and thus the rate at which sediment is delivered to deposi

tional basins

3. The rate of basin subsidence together with rates of sea-level rise or fall

4. The size and shape of the basins

The processes that may cause basin subsidence are discussed briefly in Section 16.2

(see Figure 16.2). The rate of basin subsidence coupled with sea level fluctuations

controls the available space in which sediments can accumulate (accommodation;

see Fig. 13.15) at any given time, as well as affecting sediment transport and depo

sition. Thus, owing to continued subsidence, thousands of kilometers of sedi

ments may accumulate even in shallow-water basins.

The purpose of basin analysis is to interpret basin fills to better understand

sediment provenance (source), paleogeography, and depositional environments in

order to unravel geologic history and to evaluate the economic potential of basin

sediments. Basin analysis incorporates the interpretive basis of sedimentology

(sedimentary processes); stratigraphy (spatial and temporal relations of sedimentary

rock bodies); facies and depositional systems (organized response of sedimentary

products and processes into sequences and rock bodies of a contemporaneous or

time-transgressive nature); paleooceanography; paleogeography, and paleoclima

tology; sea-level analysis; and petrographic mineralogy as a means of interpreting

sediment source (Klein, 1987; 1991). Further, biostratigraphy provides a means of

establishing a temporal framework for correlating time-equivalent facies and sys

tems and to constrain timing of specific events, and radiochronology allows, in ad

dition, the dating of specific sedimentological events and stratigraphic boundaries.

Recent research in sedimentary geology and basin analysis has focused particular

ly on analysis of sedimentary facies, cyclic subsidence events, changes in sea level,

ocean circulation pattes, paleoclimates, and life history.

Depositional models are being increasingly used to better understand the

processes of basin filling and the effects of varying basin-filling parameters such

as sediment supply and sediment flux into basins (e.g., Jones and Frostick, 2002),

grain size, basin subsidence rates, and sea-level changes (e.g., Tetzlaff and Har

baugh, 1989; Angevine, Heller, and Paola, 1990; Cross, 1990; Slingerland, Har

baugh, and Furlong, 1994; Miall, 2000, Chapters 7, 9). Models may be either

geometric or dynamic. Geometric models begin by specifying the geometry of the

depositional system rather than calculating it as part of the model. Dynamic mod

els begin with consideration of the transport of sediment in the basin and use

some form of approximation to the basic laws that govern sediment transport and

deposition.

16.6 TECHNIQUES OF BASIN ANALYSIS

Analyzing the characteristics of sediments and sedimentary rocks that fill basins,

and interpreting these characteristics in terms of sediment and basin history, de

mands a variety of sedimentological and stratigraphic techniques. These tech

niques require the acquisition of data through outcrop studies and subsurface

methods that can include deep drilling, magnetic polarity studies, and geophysi

cal exploration. These data are then commonly displayed for study in the form of

maps and stratigraphic cross sections, possibly using computer-assisted tech

niques. In this section, we look briefly at the more common techniques of basin

analysis.

Measuring Stratigraphic Sections

16.6 Te chniques of Basin Analysis

569

To interpret Earth history through study of sedimentary rocks requires that we

have detailed, accurate information about the thicknesses and lithology of the

stratigraphic successions with which we deal. To obtain this information, appro

priate stratigraphic successions must be measured and described in outcrop

and/ or from subsurface drill cores and cuttings. We refer to this process of study

ing outcrops as "measuring stratigraphic sections"; however, the process also in

volves describing the lithology, bedding characteristics, and other pertinent

features of the rocks. Samples for mineralogic or paleontologic analysis may also

be collected and keyed to their proper position within the measured sections.

Thus, measuring and describing stratigraphic sections is commonly the starting

point for many geologic studies, and the measured-section data become an indis

pensable part of the studies. Such stratigraphic sections are referred to throughout

this book; see, for example, Figure 14.12.

A variety of teciques are available for measuring stratigraphic sections,

depending upon the nature of the stratigraphic succession and the purpose of the

study. The useful little book by Kottlowski (1965) describes these various meth

ods, and the equipment needed to carry out measurements, in considerable detail.

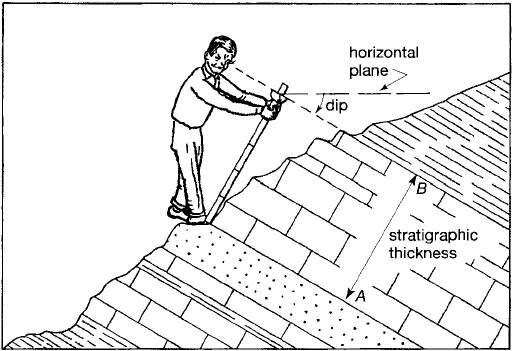

One of the most common methods involves use of a Jacob staff. A Jacob staff is a

lightweight metal or wood pole (rod) marked in graduations of feet or meters. It

is commonly cut to about eye-height and is used in conjunction with a Brunton

compass placed at or near the top of the staff. The technique is illustrated in

Figure 16.16. The clinometer of the Brunton compass is set at the dip angle of the

beds, allowing the staff to be inclined normal to the bedding to determine the true

stratigraphic thickness of the bed or beds. By stepping uphill and making a suc

cession of measurements, comparatively thick sections of strata can be measured.

After measuring several meters of section, the geologist commonly stops measur

ing for a time to describe the lithology and other pertinent features of the section

before resuming measurement. A lithologic column, together with appropriate de

scriptive notes, is recorded in a field notebook.

Preparing Stratigraphic Maps and Cross Sections

Stratigraphic Cross Sections

Once stratigraphic sections have been measured and described, they can be used

to prepare stratigraphic cross sections. Stratigraphic cross sections are used exten

sively for correlation purposes and structural interpretation, as well as for study

Figure 16.16

Schematic illustration of the jacob-staff technique for

measuring the thickness of stratigraphic units. By set

ting the clinometer of a Brunton compass attached

to the jacob staff to the dip angle of the beds, the

staff can be held normal to the bedding planes, yield

ing the true stratigraphic thickness (AB) of the mea

sured unit. [From Kottlowski, F. E., 1965, Measuring

stratigraphic sections: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston,

New York, Fig. 3.2, p. 63.]

570

Chapter 16 I Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentation

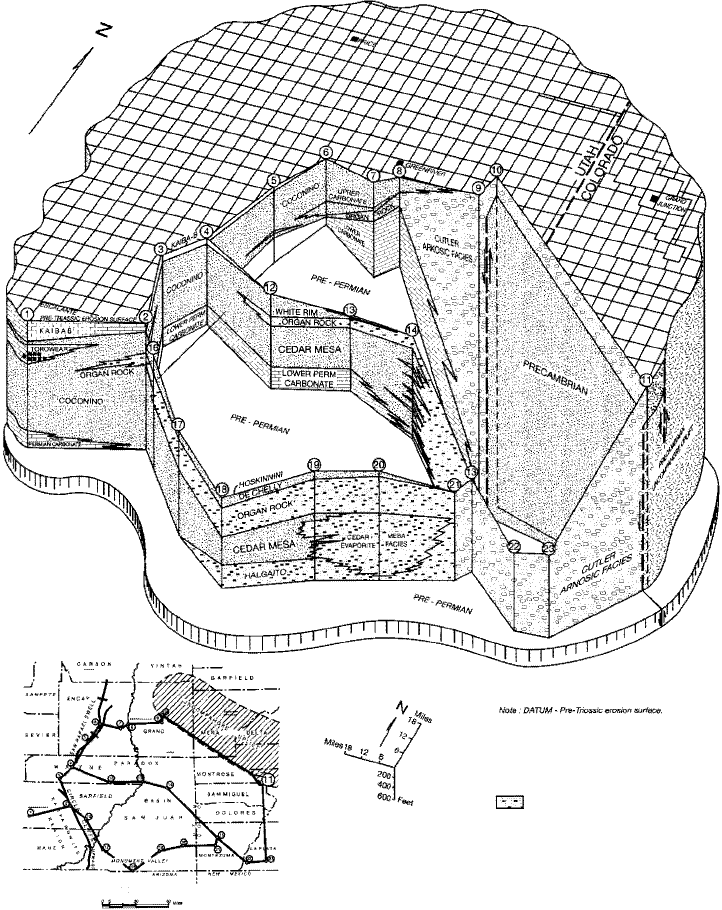

Fire 16.17

Schematic illustration of a

fence diagram showing in

tertonguing facies relation

ships in Permian strata

across the Paradox Basin,

Utah and Colorado. [From

Kunkle, R. P., 1958, Permi

an stratigraphy of the Para

dox Basin, in Sanborn, A.

(ed.), Guidebook to the ge

ology of the Paradox Basin,

Intermountain Association

of Petroleum Geologists,

Ninth Annual Field Confer

ence, Fig 1, p. 165.]

of the details of facies changes that may have environmental or economic signifi

cance. Cross sections may be drawn to illustrate local features of a basin, often in

conjunction with preparation of lithofacies maps (described below), or they may

depict major stratigraphic successions across an entire basin. In addition to mea

sud outcrop sections, the formation needed to prepare stragraphic cross sec

tions may be obtained from subsurface lithologic logs (which are prepared by

study of drill cores and cuttings) and/or mechanical well logs (petrophysical

logs). Most stratigraphic cross sections depict in two dimensions the lithologic

and/ or structural characteristics of a particular stratigraphic unit, or units, across

a

given geographic region. Several examples of such cross sections are given in

preceding chapters of this book. See, for example, Figure 12.15. Stratigraphic in

formation may be presented also as a fence diagram. These diagrams attempt to

give a three-dimensional view of the stratigraphy of an area or region (Fig. 16.17).

Thus, they have the advantage of giving the reader a better regional perspecve

on the stratigraphic relationships. the other hand, they are more difficult to

EXPLANATION

W NE

BE • a • ndstone, & $ll

SCALE

� CAONAT-&one & dolomite

� ARKE GRANE WH

IGNES and METAMOIC C

LOCAT•ON MAP

- p " f f"

� EVORITES - andrite & sum

16.6 Te chniques of Basin Analysis

571

construct than conventional two-dimensional diagrams, and parts of the section

are hidden by the fences in front.

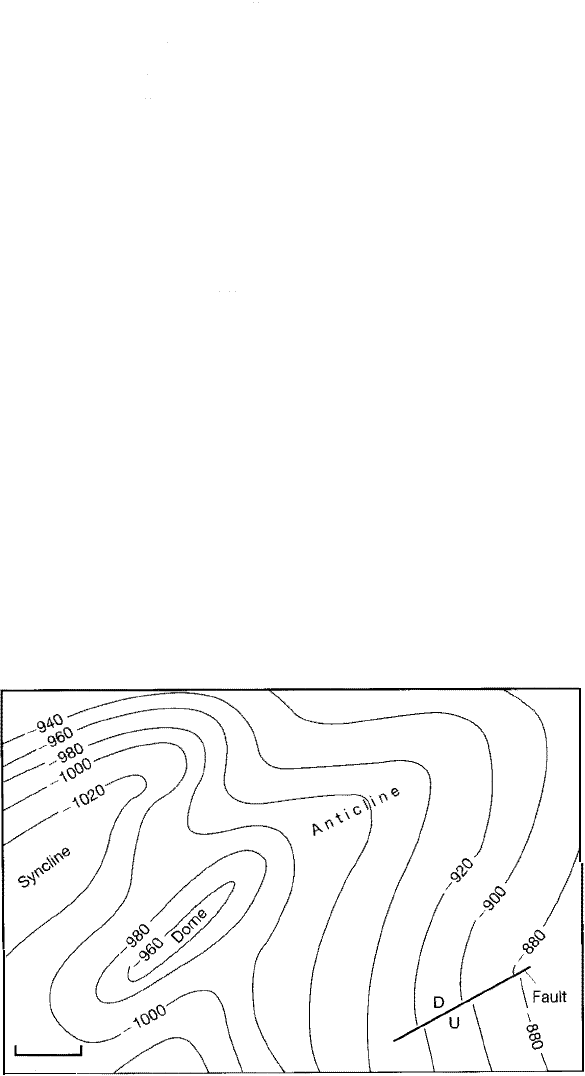

Structure-Contour Maps

It is often desirable in basin studies to determine the regional structural attitude of

the rocks as well as the presence of local structural features such as anticlines and

faults. Structure-contour maps are prepared for this purpose. These maps provide

information about a basin's shape and orientation and the basin-fill geometry.

Structure-contour maps are prepared by drawing lines on a map through points of

equal elevation above or below some datum, commonly mean sea leveL Eleva

tions are typically determined on the top of a particular formation or key bed at a

number of control points. Elevation data may be obtained through outcrop study

and/ or subsurface interpretation of mechanical or lithologic well logs. After con

trol points are plotted on a base map, a suitable contour interval is selected, and

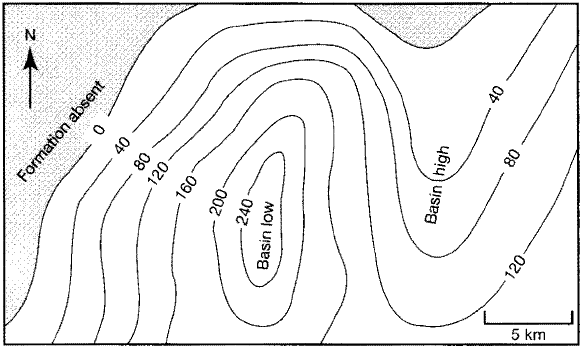

structure contour lines are drawn by hand or by use of computers. Figure 16.18

shows an example of a strucre-contour map.

Structure contours may also be prepared on the top of prominent subsurface

reflectors from seismic data (Chapter 13). Depth to a particular reflector may be

plotted initially as two-way travel time. Thus, the initial map shows contour lines

of equal travel time. If the seismic-wave velocity can be determined from well in

formation, the travel times can be converted to actual deps, allowing maps to be

redrawn in terms of actual elevations on the reecting horizon.

Structure-contour maps can reveal e locations of subbasins or depositional

centers within a major basin as well as axes of uplift (anticlines, domes). Structur

al features may be related also to syndepositional topography. Thus, analysis of

these maps can provide clues to local paleogeography and facies pattes. Struc

tural maps are useful also in economic assessment (e.g., petroleum exploration) of

basins.

Isopach Maps

Isopachs are contour les of equal thickness. An isopach map is a map that shows

by means of contour lines the thickness of a given formation or rock unit. A map

that

shows the areal variation in a specific rock type (e.g., sandstone) is an isoth

map. The thickness of sediment in a basin is determined by the rate of supply of

sediment and the accommodation space in the basin, which in turn is a function of

N

t

5 km

Figure 16.18

Schematic illustration of a structure-contour

map drawn on the top of a formation. The

contour interval is 20 m. The negative con

tour values indicate that this formation is lo

cated below sea level and is thus a buried

(subsurface) formation. Note the presence

of a syncline, dome, anticline, and fault.

572 Chapter 16 1 Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentation

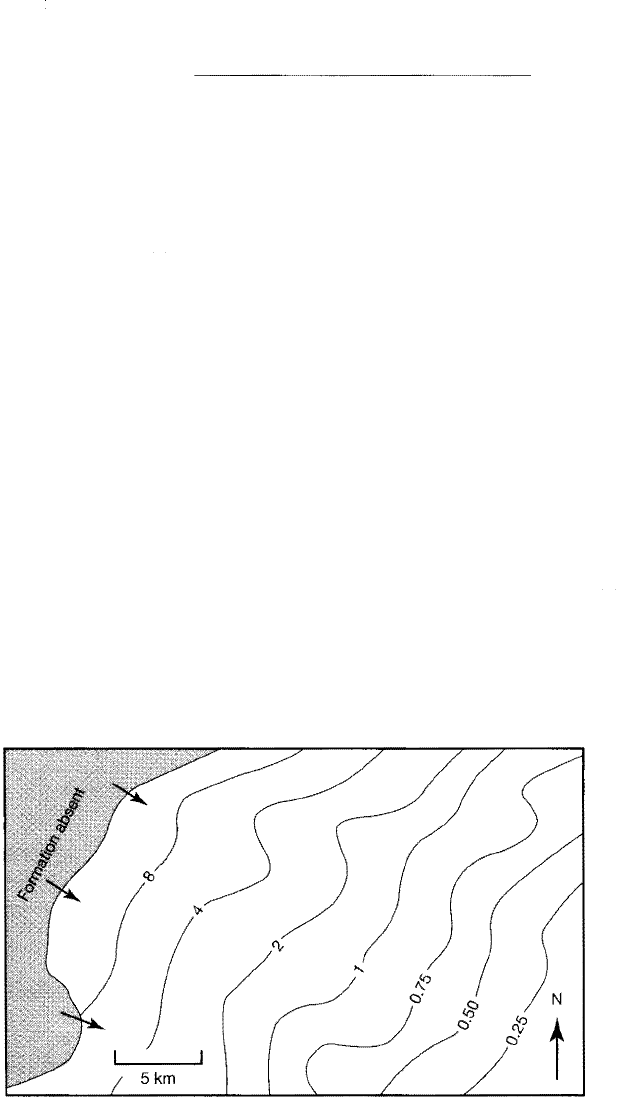

Figure 16.19

basin geometry and rate of basin subsidence. Abnormally thick parts of a stra

graphic unit suggest the presence of major depositional centers in a basin (basin

lows), whereas abnormally thin parts of the unit suggest predepositional highs or

possibly areas of postdepositional erosion. Isopach maps thus provide informa

tion about the geometry of the basin immediately prior to and during sedimenta

tion. Furthermore, analysis of a succession of isopach maps in a basin can provide

information about changes in the structure of a basin through time.

To construct an isopach map, the thickness of a formation or other strati

graphic unit must be determined from outcrop measurements and/ or subsurface

well-log data at numerous control points. The thickness of the unit at each of these

conol points is entered on a base map, and the map is contoured in the same way

that a structure-contour map is prepared. Figure 16.19 is an example.

Pa leogeologic Ma

p

s

Paleogeologic maps are maps that display the areal geology either below or above

a given stratigraphic unit. Imagine, for example, that we could strip off the rocks

that make up a particular formation (and all the rocks above that formation) to re

veal the rocks beneath-the rocks on which the formation was deposited. We

could then construct a geologic map on top of these underlying formations. Such

a map has been referred to as a subcrop map (Krumbein and Sloss, 1963). In a sim

ilar manner, the rocks above a formation or rock body may also be mapped. This

kind of map, looked at as though from below, is called a worm's eye view map or

supercrop map. Subcrop and worm's eye maps are commonly constructed at un

conformity boundaries; however, they can be constructed at the top and base of

any distinctive rock unit, whether or not an unconformity is present. The ma

purpose of such maps is to illustrate paleodrainage patterns, pattern of basin fill,

shifting shorelines, or gradual burial of a preexisting erosional topography (Miall,

2000, p. 250). To construct paleogeologic maps requires identification of the strati

graphic units that lie immediately below (or above) a given formation or other

satigraphic unit at numerous control points. Such data are gathered from out

crops or from subsurface well logs.

Lithofa cies Ma

p

s

Facies maps depict variation in lithologic or biologic characteristics of a strati

graphic unit. The most common kinds of facies maps, and the only kind discussed

here, are lithofacies maps, which depict some aspect of composition or texture.

Maps based on faunal characteristics are biofacies maps. Many kinds of lithofacies

Example of an isopach map of a hypothetical

formation drawn at a contour interval of

40 m. Note that the formation thickens to

more than 240 m in the basin low (deposi

tional center), thins over a basin high, and

thins to zero along the northwest and north

sides of the map.

16.6 Te chniques of Basin Analysis

573

maps are in use. Some are plotted as ratios of specific lithologic units (e.g., the

ratio of siliciclastic to nonsiliciclastic components) or as isopachs of such units

[e.g., sandstone isopach (or isolith) maps, limestone isopach (or isolith) maps].

Others examine the relative abundance and distribution of three end-member

components (e.g., sandstone, shale, limestone). Two kinds of lithofacies maps are

discussed here to illustrate the method: clastic-ratio maps and three-component

lithofacies maps. Additional examples are given in Krumbein and Sloss (1963) and

Miall (2000).

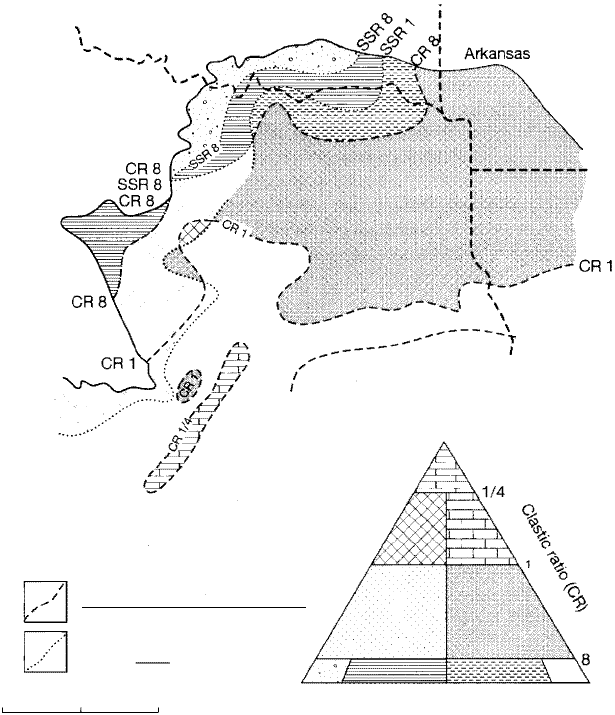

Clastic-ratio maps are maps that show contours of equal clastic ratio, which

is defined as the ratio of total cumulative thickness of siliciclastic deposits to the

thickness of nonsiliciclastic deposits, for example,

(conglomerate + sandstone + shale)

(l

imestone + dolomite + evaporite)

Values are computed for a number of control points, from outcrop or subsurface

data, and plotted on a map. The map is then contoured in the same manner as that

described for isopach maps. example is shown in Figure 16.20. Clastic-ratio

maps are usel for showing the relationship of lithologic units along the margin

of a basin in which both siliciclastic and nonsiliciclastic deposits accumulated.

Such maps provide limited information also about the location of the siliciclastic

sediment source.

Three-component (tangle) lithofacies maps show by means of patterns or

colors the relative abundance, within a formation or other stratigraphic unit, of

three principal lithofacies components. Figure 16.21 is an example of such a map

based on the relative thickness of sandstone, shale, and limestone. A teary dia

gram, called the standard diagram (inset in Fig. 16.21), is drawn using the three

lithofacies components as end members. The triangle is subdivided into fields,

each of which is indicated by a suitable patte or color. The thickness of each end

member component is measured at as many control points in outcrop or in the

subsurface as practicaL The relative values (normalized to 100 percent if neces

sary) at each control point are plotted on the teary diagram. The clastic ratio and

sand-shale ratio at each data point are calculated and used to draw contour lines

of clastic ratio (CR) and sand/shale ratio (SSR) on the map. These contour lines

allow the map to be divided into selected pattern areas corresponding to the pat

terns in the standard triangle. In this example, a progressive change in facies from

dominantly clastic material in the northwest part of the map to a section com

posed dominantly of limestone in the southe part is evident.

Figure 16.20

Example of a clastic-ratio (clastic/nonelastic)

map. The progressive increase in the ratio

from southeast to northwest across the map

indicates a progressively increasing percent

age of siliciclastic components in the strati

graphic section toward the northwest. Thus,

the source of the sediments must have been

located somewhere to the northwest. The

small arrows show the probable direction of

sediment transport.

57 4

Chapter 16 I Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentatio

n

Te xas

SSR 1

Fire 16.21

Oklahoma

I

I

I

I

I

\

.

Limestone

I

I

-

-

CR 1/4

1 Louisiana

I

I

Triangle lithofacies map of the Creta

ceous Trinity Group, southern U.S.A.

Note that the stratigraphic section

changes from predominantly siliciclastic

in the northwest part of the map to

predominantly limestone in the south

ern

part. Not all lithofacies shown in

the lithofacies triangle (e.g., shale) are

actually present in the mapped area.

[Redrawn from Krumbein and Sloss,

1963, Fig. 12.1 1, p. 464, as modified

from Forgotson, 1960.]

0

o

"

/

/

/

/

-

-

---

--

-

-

CR 1/4

/

-

Clastic ratio (CR)

sandstone shale

limestone + dolomite + dolomite

Sand/shale ratio (SSR)

sand

shale

100

200

Kilometers

Sandstone 8

1/8 Shale

Sandstone/shale ratio (SSR)

The degree of "mixing" of three rock components in a stratigraphic section

can be calculated mathematically by applying an entropy-like function. The func

tion is set up so that equal parts of (for example) sandstone, shale, and limestone

have an entropy value of 100. As the proportion of one end member or another in

creases, the entropy value becomes smaller, approaching zero as the composition

approaches that of a single end member. An entrop

y

map can be prepared from

these data by using an overlay of the entropy function on the lithofacies triangle

(Krumbein and Sloss, 1963, p. 467; Forgotson, 1960).

If more than three lithofacies are present in a stratigraphic section, the addi

tional lithofacies must be omitted (and the remaining three lithofacies normalized

to 100 percent) or combined with other lithofacies to yield a total of three lithofa

cies. For example, if a conglomerate facies is present, it could be combined wi

the sandstone facies, or an evaporite facies might be combined with a limestone

facies. Three-component lithofacies maps provide a convenient means of visualiz

g the relative importance of each lithofacies throughout a geographic area. Like

clastic-ratio

maps, however, they provide only a very rough guide to depositional

environments and sediment-source locations.

Computer-Generated

Maps

All of the maps discussed above can be drawn by hand, and geologists have been

drawing them this way for many years; however, such maps are now constructed

16.6 Techniques of Basin Analysis

575

more and more by computer. Computer application is particularly prevalent in

the petroleum industry, where basin analysis is a commonplace procedure. Com-

puters are able to handle large quantities of data, such as stratigraphic and struc-

tural data obtained from well records, and they allow these data to be easily

manipulated for a variety of statistical and mapping purposes. Appropriate base

maps are stored in the computer and the locaons of outcrop sections and subsur-

face wells can be easily plotted on these maps. Lithologic, structural, and strati-

graphic data obtained from study of outcrop and subsurface sections are likewise

stored in the computer. Selected data (e.g., thickness of lithologic units, structural

elevations) can be retrieved as needed and added to the base maps, which can

then be contoured by the computer by using appropriate software and special

printers to draw the maps. Thus, any of the maps described above can be generat-

ed by computer, as well as oer kinds of maps such as trend-surface maps.

Tr end-surface analysis allows separation of map data into two components: re-

gional trends and local fluctuations. The regional trend is mathematically sub-

tracted by the computer, leaving residuals, which correspond to local variations.

For example, the regional structural trend might be extracted from a structure-

contour map to more clearly reveal the nature of local structural anomalies.

Computer-generated maps are not necessarily better or more accurate than hand-

drawn maps. Their principal advantage is in the ease and rapidity with which

they can be drawn. See, for example, Robinson (1982) and Jones, Hamilton, and

Joson (1986).

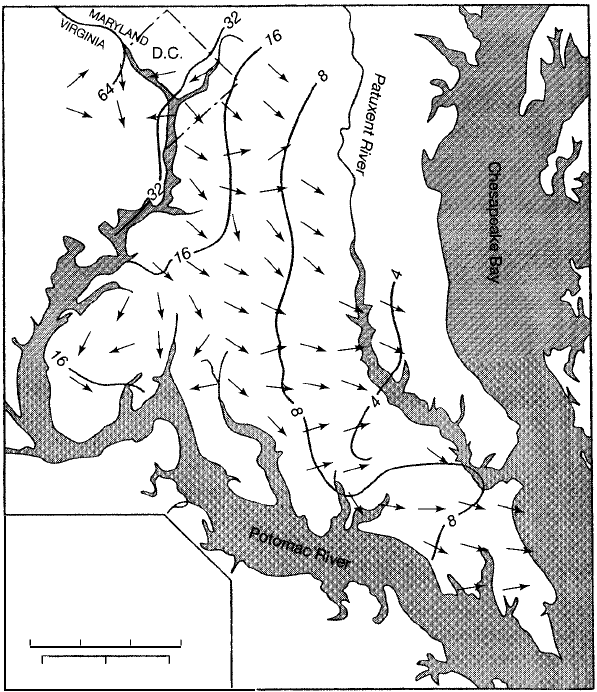

Pa leoent Analysis and Pa leoent Maps

Paleocurrent analysis is a tecique used to determine the ow diction of an

cient currents that transported sediment into and within a deposional basin,

which reflects the local or regional paleoslope (see Chapter 4, Section 4.6). By in

ference, paleocurrent analysis also reveals e direction in which the sediment

source area, or areas, lay. Further, it aids in understanding the geometry and trend

of lithologic units and in interpretation of depositional environments. Paleocur

nt analysis is accomplished by measuring the orientation of directional features

such as sedimentary structures (e.g., flute casts, ripple marks, cross-beds) or the

long-axis orientation of pebbles. Numerous orientation measurements must be

made within a given stratigraphic unit to obtain a statistically reliable paleocur

nt trend. Grain-size trends, lithologic characteristics, and sediment thickness

may also have directional significance when mapped, as previously discussed.

example of a paleocurrent map, constructed mainly on the basis of cross-bedding

orientation, is shown in Figure 16.22. Note that the average (statiscal) paleoflow

direction indicated by this map is from the northwest to southeast, suggesting that

the sediment source area lay somewhere to the northwest. For more detailed dis

cussion of the application of paleocurrent alysis to interpretation of sediment

dispersal patter and basin-filling mechanisms, see Potter and Pettijohn (1977,

Chapter S).

Siliciclastic Petrofacies (Provenance) Studies

The composition of siliciclastic sediments that ll sedimentary basins is deter

mined to a large extent by the lithology of the source rocks that fished sedi

ment to the basin, as well as by the climate and weathering conditions of the

source aa. Therefore, analysis of the particle composition of siliciclastic mineral

assemblages (and rock fragments) provides a method of working backward to un

derstand e nature of the source aa. We commonly refer to such study as prove

nance study, where provenance is considered to include the following: (1) the

lithology of the source rocks, (2) the tectonic setting of the source aa, and (3) e

576

Chapter 16 I Basin Analysis, Te ctonics, and Sedimentation

Figure 16.22

Example of the use of paleocurrent data

to locate source areas, Brandywine gravel

of Maryland. The contours show modal

grain size (in mm). [From Potter, P. E., and

F. ]. Pettijohn, 1977, Paleocurrents and

basin analysis, Fig. 8.9, p. 282. Reprinted

by permission of Springer-Verlag, Berlin.]

"

Cross-bedding

direction, moving

average

._ Modal size (mm)

0 5 10 15 mi

0

10

20 km

climate, relief, and slope of the source area. Provenance studies provide important

information about the paleoclimatology and paleogeography of the basin setting.

The lithology of the source rocks is interpreted on the basis of the kinds of

minerals and rock fragments present in siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, particular

ly in sandstones and conglomerates. For example, the presence of abundant alkali

feldspars suggests derivation from granitic source rocks; abundant volcanic rock

fragments suggest derivation from volcanic source rocks; and so on. The siliciclas

tic mineralogy also provides information about the tectonic setting (continental

block, magmatic arc, collision orogen); sediment derived from continental block

settings is likely to be enriched in quartz and alkali feldspars; sediment derived

from a magmatic arc is dominated by volcanic rock fragments and plagioclase

feldspars; and sediment stripped from highlands along orogenic collision belts is

characterized particularly by an abundance of sedimentary and metasedimentary

rocks fragments. Climate, relief, and slope of the source area are more difficult to

interpret from siliciclastic mineral assemblages, but some clues are provided by

quartz/feldspar ratios and by degree of weathering of feldspars. The essentials of

provenance analysis are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5, Section 5.6. Zuffa

(1985); Morton, Todd, and Haughton (1991), and Johnsson and Basu (1993) pro

vide a broader and more detailed view of provenance analysis.

Geophysical Studies

Geophysical investigations, including both seismic and paleomagnetic studies of

various kinds, play an important role in basin analysis. Seismic techniques are