Boggs S. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

346

Chapter

1

0 I Siliciclastic Marine Environments

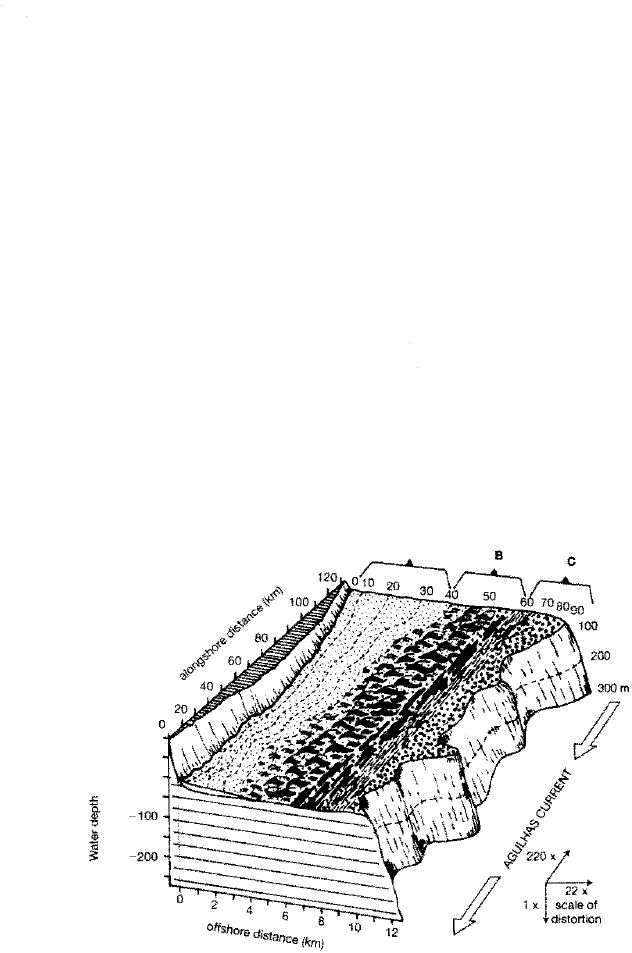

gure 10.9

Current off the Asian coast, and the Agulhas Current off the southeast tip of Africa

are examples of some prominent ocean currents.

These semipermanent ocean currents intrude onto some shelves with suf

cient bottom velocity to transport sandy sediment. About 3 percent of modem

shelves are dominated by these ocean currents, which operate most effectively on

the outer shelf. Modern examples of such shelves include the northweste Gulf

of Mexico, which is affected by the Gulf Stream System; shelves swept by the

Panama and North Equatorial Current off the northeast coast of South America;

the Ta iwan Strait between Ta iwan and mainland China, which is intruded by a

branch of the Kuroshio Current flowing north from the Philippines; and the outer

shelf of southe Africa, which is crossed by the southward-flowing Agulhas Cur

rent of the weste Indian Ocean. These currents commonly contribute little if any

new sediment to the shelf, but they are capable of transporting significant vol

umes of fine sediment along the shelf. Some achieve bottom velocities eat

enough to transport sandy sediment and create sand waves and other bedforms,

for example the Kuroshio Current (Boggs, Wang, and Lewis, 1979) and the Agul

has Current (Fleming, 1980).

Sediment on such shelves raked by intruding ocean currents is largely relict,

but it is commonly reworked by intruding currents to form sand waves (dunes),

sand ribbons, and coarse sand and gravel lag deposits. The best-documented ex

ample of this type is the southeastern shelf of South Africa, which is intruded by

the Agulhas Current of the Indian Ocean (Fleming, 1980). Sand waves up to 17m

high with wave lengths up to 700 m occur sand-wave fields as much as 10

wide and 20 km long (Fig. 10.9). The Taiwan Strait between Ta iwan and China is

another broad shelf invaded by ocean currents that create extensive sand-wave

fields (Boggs, 1974).

Shelf ansport by Density Cuents

Density currents are created by density diffences within water masses. The

buoyant plumes and underflows described above and illustrated in Figure 10.5, as

well as nepheloid flows, are all density currents driven by density differences aris

ing from suspended sediment. In arid climates, excessive nearshore evaporation

may generate dense brines that flow seaward along the bottom as an underflow.

Such underflows could conceivably occur also on shelves whe cold surface wa

ters sink and flow seaward. Density currents generated as a result of variations in

A

Sediment transport by the Agulhas Current o

the southeastern tip of Africa. Sand in the current

controlled central shelf (B) migrates under the

influence of the Agulhas Current; sand-wave

fields are up to 20 km long and

1

0 km wide, and

individual sand waves are up to

1

7 m high. Black

streaks indicate sand ribbons. The stippled pat

tern indicates coarse lag deposits in the sand-de

pleted outer shelf (C). The nearshore sediment

wedge (A) is dominated by wave processes.

[From Fleming, B. ,

1

980, Sand transport and

bedforms on the continental shelf between Dur

ban and Port Elizabeth (southeast Africa conti

nental margin): Sed. Geology, v. 26, Fig.

1

5, p.

1

94, reproduced by permission of Elsevier Sci

ence Publishers, Amsterdam.]

+100

I

MSL

0

12

10.2 The Shelf Envinment

347

temperature or salinity are not significant agents of shelf transport, and no mod-

e shelf is dominated by such processes.

Eects of Sea-Level Change on Shelf anspo

Because geographic environments shift rapidly and change their form during sea

level fluctuations, sea-level changes constitute an important, and sensitive, depo

sitional variable on shelves. They can affect both erosional and depositional

presses and thus the kinds of sediments deposited on shelves. Among other

things, sea-level changes are an important factor in establishing the stratigraphic

architecture of shelf sediments, a topic that we explore in Chapter 13. See also

Wa lker and James (1992) and Reading and Levell (1996).

Biological Activities on Shelves

Mode contental shelves are among the environments most densely populated

by organisms, and the geologic record suggests that ancient epeiric seas were also

inhabited by large populations of organisms. The shelf floor is habitat for highly

diverse invertebrate organisms such as molluscs, echinoderms, corals, sponges,

worms, and arthropods. Both infauna and vagrant and sessile epifauna are repre

sented. Organisms are most abundant in lower-energy areas of the shelf, and the

eatest populations occur on the ier shelf just below the wave base.

Organisms on siliciclastic-dominated shelves are particularly important as

agents of bioturbation. Both type and abundance of bioturbation structures vary

with sediment type and water depth. As discussed in Chapter 4, many burrows in

the nearshore high-energy zone are escape structures that tend to be predominantly

vertical. The burrow style changes to oblique or horizontal feeding structures with

deepening of water across the shelf. general, muddy sediments of the shelf are

more highly bioturbated than are sandy sediments, and physical sedimentary struc

tures in these sediments may be almost completely obliterated by bioturbation. By

contrast, only a few species of organisms can survive in the very hi energy

nearshore shelf and beach zone. Therefore, sandy sediments of the beach-shelf

transition zone are dominated by physical structures such as cross-bedding rather

than bioturbation structures. Nonetheless, some bioturbation structures may be

psent if they escape destruction by reworking. Sandy layers deposited in deeper

water on the shelf may be bioturbated to some degree in their upper part. In addi

tion to their importance as bioturbation agents, some organisms produce fecal pel

lets from muddy sediment; these pellets may become hardened and coherent

enough to behave as sand grains. Organisms with shells or other fossilizable hard

parts also leave remains that may be preserved to become part of the sediment

record.

Ancient Siliciclastic Shelf Sediments

Although recognition of ancient she sediments is aided by study of modern con

tinental shelves, modern shelves are not necessarily good analogs of ancient

sh

elves. For example, the prevalence of relict sediments on modern shelves may

be atypical. Conversely, some structures believed to be diagnostic of ancient shelf

sediments, notably storm-generated hummocky cross-stratification, have appar

ently not been recoized in modern shelf environments. In general, ancient shelf

sediments appear to be distinguished by the following: (1) tabular shape, (2) ex

tensive lateral dimensions (thousands of square kilometers) and great thickness

(hundreds of meters), (3) moderate compositional maturity of sands with quartz

do

minating feldspars and rock fragments, (4) generally well-developed, even, lat

erally extensive beddg, (5) storm beds in some shelf deposits, (6) wide diversity

348

Chapter 10 I Siliciclastic Marine Environments

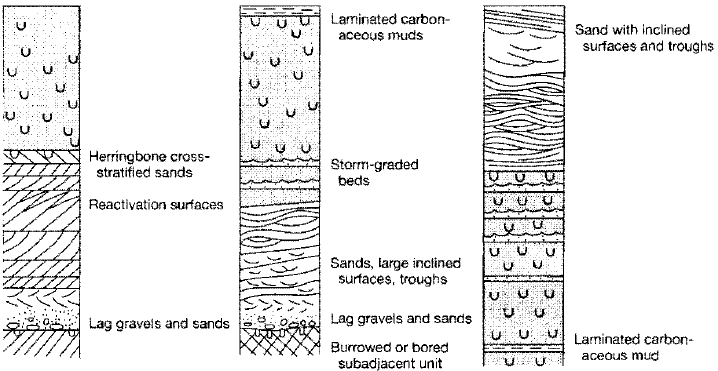

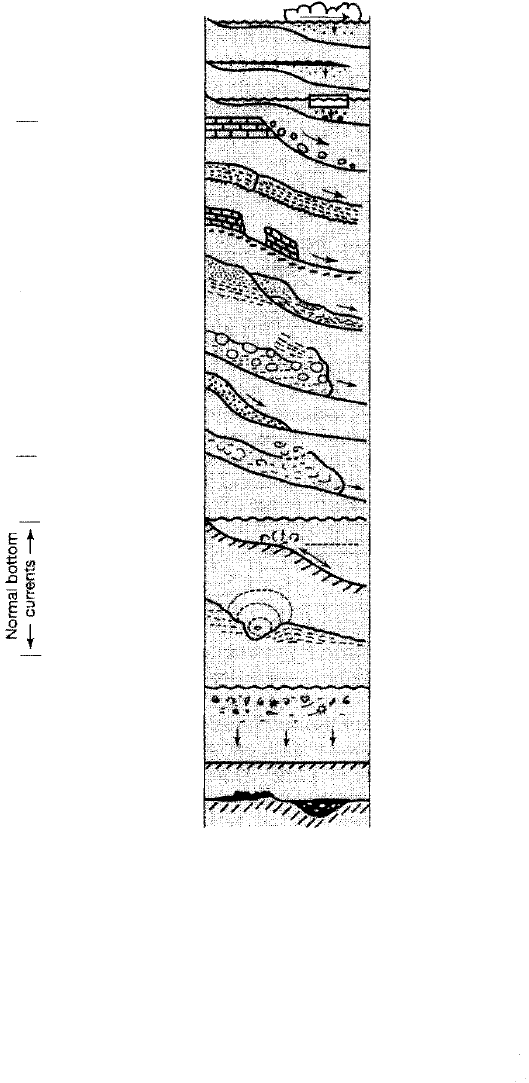

Figure 10.10

Idealized diagrams illustrat

ing typical fining-upward

transgressive shelf succes

sions on (A) a tide-dominat

ed shelf and (B) a

storm-dominated shelf, and

a coarsening-upward re

gressive shelf succession (C)

on a storm-dominated shelf.

[After Galloway, W. E., and

D. K. Hobday, 1983, Ter

rigenous clastic depositional

systems. Fig. 7.14, p. 159,

Fig. 7.15, p. 160, Fig. 7.17,

p. 162, reprinted by permis

sion of Springer-Verlag, Hei

delberg.]

and abundance of normal marine fossil organisms, and (7) diagnostic associations

of trace fossils.

More specific characteristics are related to deposition under tide-dominated

or storm-dominated conditions. The deposits of ancient tide-dominated shelves

are characterized particularly by cross-bedded sandstone. Paleocurrents are main

ly unimodal, apparently because of ancient regional net-sediment-transport paths,

although bipolar cross-stratification is present locally (Dalrymple, 1992). Reactiva

tion surfaces are abundant. Ancient storm-dominated shelf deposits likely contain

a greater proportion of mud than do tide-dominated deposits, and hummocky

cross-stratification and storm layers are common (but not in modern deposits!).

Several kinds of vertical successions may thus be generated in shelf sedi

ments, depending upon whether deposition takes place during transgression or

regression and depending upon the dominant type of shelf processes operating

during deposition. It is difficult to generalize about these successions except to say

that transgression tends to produce fining-upward successions that may begin

with coarse lag deposits, and regression produces coarsening-upward succes

sions. Some idealized vertical shelf successions produced under different postu

lated sedimentation conditions are illustrated in Figure 10.10. These successions

should be considered only as working models. Actual transgressive and regres

sive successions may differ markedly in detail from these idealized profiles.

Ancient shelf deposits are known from stratigraphic units of all ages and all

continents. They are probably the most extensively preserved rocks in the geolog

ic record. Readers interested in pursuing case histories of specific shelf deposi

can consult the extensive list of pertinent references provided by Leeder (1999, p.

463); these references include some of the best accounts of ancient shelf deposi

on the basis of study of Cretaceous sediments deposited in the Western Interior

Seaway of North America. Additional accounts of these deposits, derived from

study of magnificent exposures stretching from Colorado to Alberta, can be found

in Bergman and Snedden (1999).

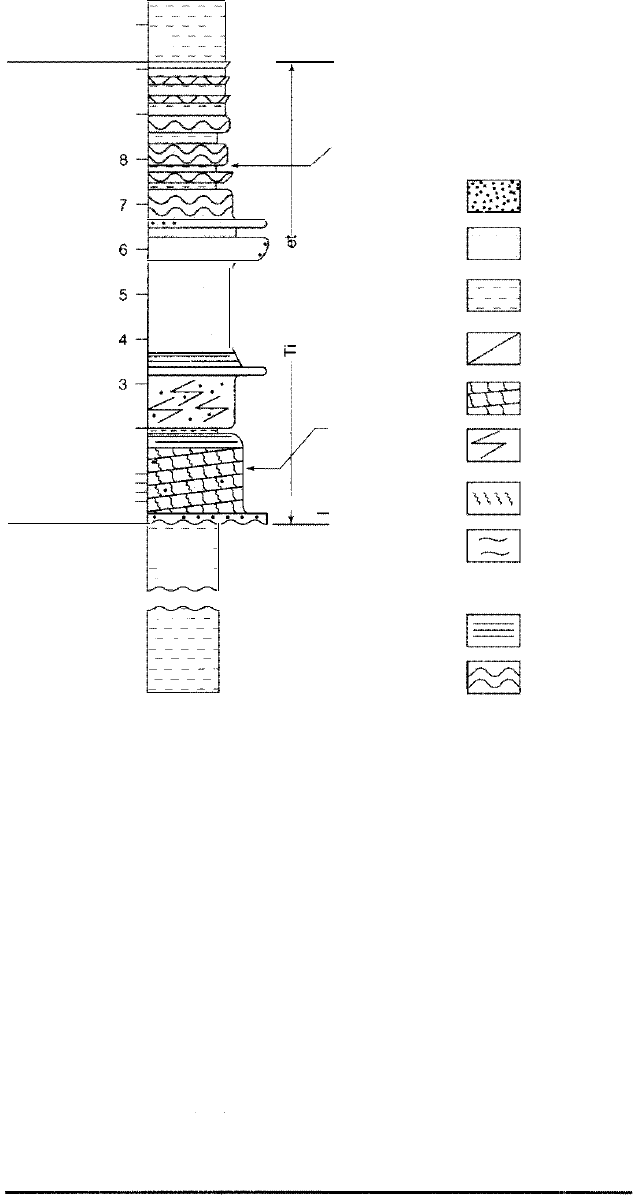

One example of shelf deposits from the Western Interior Seaway is shown in

Figure 10.11. Baneee (1991) describes Cretaceous sandstones of southern Alberta,

Canada, which he interprets as tidal sand sheet facies. One of these is the (lower

most) Sunkay Member of the Lower Cretaceous Alberta Group. This sandstone

unit, approximately 10 m thick, rests with a sharp erosional base on nonmarine

A

Transgressive Tide

Dominated Shelf

v

v

Bioturbated

silts and muds

Large·scale cross

stratified sands

B

Tr ansgressive Storm

Dominated Shelf

c

Regressive Storm�

Dominated Shell

Burrowed, glauconitic,

si�y muds

Hummky cross

stratified sands

Hummocky cross

stratified sands

Parallel lamination

Storm-graded

beds within

shelf muds

Burrowed shelf

mud

m

11

-

10

9

8-

!

7

-

0

0

c

6-

�

5-

E

4-

j

c

3-

2

1

-

-

Beaver

Mines

�

-�---

.. - �

�

�

�

. . � ...

-

-

� �

-

. . . .

.

. j

.

.

. . .

.,

�

-

�

-

u

�

c

-

-

-

-

-

u

-

.........

-

-

i

.

.

.

.

.

..

�

..

.

-

� ---

- � -- �

----

:�

� � �

-

- -

--

D

.

�

I

:

Fluvial (?)

1111 I

EE��

Dinoflagellates

(Albian)

Storm layer

Storm layer

Storm layer

Foraminifer

(S accamina?)

Tr ansgressive

lag

10.3 The Oceanic (Deep-Water) Environment

349

�

quartchert pebbles

�

sandstone

shale

interbedded lithology

high-anglj

cross bed

low-angle

mud-draped foresets

!laser

parallel

} """'"'

wavy

gu 10.11

Vertical succession of sandy

tidal shelf deposits in the

Sun kay Sandstone Member of

the Lower Cretaceous Alberta

Group, southern Alberta,

Canada.

Symbols in the grain

size scale are gvl = gravel,

cs = coarse sand,

ms = medium sand,

fs = fine sand, and m = mud

(silt-clay). [After Banerjee, 1.,

1991 , Tidal sand sheets of the

late Albian Joli Fou-Kiowa-Skull

Creek marine transgression,

Western

Interior Seaway of

North America in Smith, R. G.,

et al. (eds.), Clastic tidal sedi

mentology: Canadian Soc. Pe

troleum Geologists Mem. 16,

Fig. 9, p. 334.]

shales of the Beaver Mines Formation d is overlain by black marine shales. The

Sunkay Member consists mainly of sdstone, with a thin lag gravel deposit at

the base and a few thin interbedded conglomerate layers, interpreted as storm

layers. The succession as a whole fines upward. The basal sandstone units are

cross-bedded; the uppermost ones are characterized by flaser and wavy bedding.

Foraminifers and dinoflagellates are present in some layers. Bioturbation is not

common.

Banerjee interprets these sandstones as tidal sand sheets. 11dal interpretation

based in part on the presence of the following: cross-stratification (>20° dip and

sets 300 em thick), with thin shale drapes adhering to foreset surfaces, in the

lower part of the section; and flaser, wavy, and lenticular bedding in the upper

part. Tr ansgression deepened the water at this site, causing black marine shales to

be deposited on top of the tidal sandstones.

10.3 THE OCEANIC (DEEP-WATER) ENVIRONMENT

Inoduion

e discussion of depositional environments to this point, I have focused on the

continental, marginal-marine, and shallow-marine enviroents because much of

the preserved sedimentary record was deposited in these environments. In terms

350

Chapter 10 I Siliciclastic Marine Environments

of size of the environmental setting, however, these nonmarine and shallow-water

marine environments actually cover a much smaller area of Earth's surface than

do deep-water environments. By far, the largest portion of Earth's surface lies

seaward of the continental shelf in water deeper than about 200 m. Approximately

65 percent of Earth's surface is occupied by the continental slope, the continental

rise, deep-sea trenches, and the deep ocean oor. Even so, most textbooks that dis

cuss sedimentary environments typically give only modest coverage to oceic

environments. This bias probably exists because, as a whole, deep-water sedi

ments are much more poorly presented in the exposed rock record than are shal

low-water sediments. Deep-water deposits are less abundant than shallow-water

deposits in the exposed rock record because sedimentation rates overall are slow

er deeper water; thus, the sediment record is thinner. [ exception is the sub

marine fan environment near the base of the slope where sedimentation tes

from turbidity currents can exceed 10 m/1000 yr and turbidite sediments can

achieve thicknesses of thousands of meters (e.g., Bouma, Normark, and Barnes,

1985)]. Also, part of the sediment record of the deep seafloor may have been de

stroyed by subduction in trenches, and those deep-water sediments that have es

caped subduction have required extensive faulting and uplift to bring them above

sea level where they can be viewed. Deepwater sediments other than turbidites

have not been studied as thoroughly as shallow-water sediments-perhaps in

part because deep-water sediments have less economic potential for petroleum.

Owing to the advent of seafloor spreading and global plate tectonics concepts,

however, the deep seaoor has taken on enormous significance for geologists.

Consequently, intensive research has been focused on the continental margins and

deep seafloor since the early 1960s. Also, the continuing need to add to our fossil

fuel reserves is pushing petroleum exploration into deeper and deeper water, and

the possibility of mining manganese nodules and metallerous muds from the

seafloor is also causing increased economic interest in the deep ocean.

Deep-sea research has been particularly stimulated by the Deep Sea Drilling

Program (DSDP), which began in 1968 and shifted to the Ocean Drilling Pgram

(ODP) in 1984. Since initiation of these programs, several hundred holes have bn

drilled by DSDP and ODP teams throughout the ocean basins of the world to an

average depth below seaoor of about 300 m ( �1000 ft) and to maximum dths

exceeding 1000 m. In addition to deep coring by DSDP and ODP, many thousands

of shallow piston cores have been collected from the seafloor throughout the ocean

by marine ologists from major oceanographic institutions of the world. Also,

hundreds of thousands of kilometers of seismic profiling les (Chapter 13) have

been run in crisscross pattes across the ooean floor in an attempt to unravel the

sub-bottom structure of the ocean. Although much of this research has been aimed

at

understanding the larger scale feahtres of the ocean basins that illuminate the

origin and evolutionary history of the ocean basins along plate tectonics concepts,

many data on sedimentary facies and sedimentary environments have also been

collected. Much additional new information on ocean circulation and sediment

transport systems has also been generated by oceanographers who study ocean

bottom currents and bottom-water masses. Thus, a significant increase in under

standing of the ocean basins and the deep ocean oor has come about since the

1950s. We shall concentrate discussion here on the fundamental pcesses of sedi

ment transport and deposition on continental slopes and the deep ocean oor and

the principal types of facies developed in these environmen.

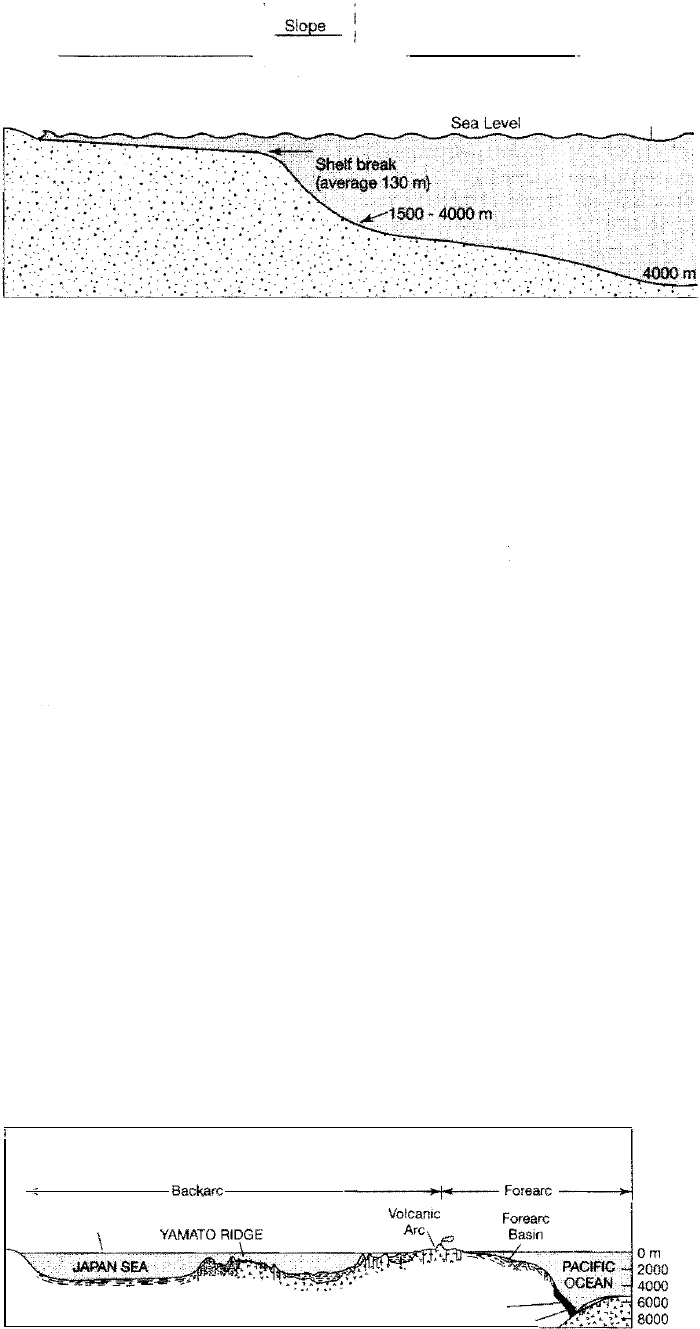

Depositional Setting

Continental Slope

e continental slope extends from the shelf break, which occurs at an average

depth of about 130 m in the modern ocean, to the deep seaoor (Fig. 10.12). The

10.3 e Oceanic (Deep-Water) Environment

351

Continental She

Average width 75 km

Average slope 1.7 m/km (0.1 °)

Cont.

:

Slope

1

width 1

110-100 km 1

1 av. slope

1

1 70 m/km

1

I Wl

I

Continental

Ri

Width 0 - 600 km

Slope 1 - 10 m/km (0.05 - 0.6")

i Abyssal

I

I

I Slope

I 1 m/km

I (0.05°)

lower boundary is typically located at water depths ranging from about 1500 to

4000 m, but locally in deep trenches it may extend to depths exceeding 10,000 m.

Continental slopes are comparatively narrow {10-100 km wide), and they dip sea

ward much more steeply than does the shelf. The average inclination of modem

continental slopes is about 4°, although slopes may range from less than 2° off

major deltas to more than 45° off some coral islands.

The origin and internal structure of continental slopes are not of primary

conce here; however, a brief description of differences in the characteristics of

continental slopes on passive {Atlantic-type) and active (Pacific-type) continental

margins is pertinent to succeedg discussion. As shown in Figure 10.4, various

kinds of barriers form the boundary between the continental shelf and the conti

nental slope. The principal kinds of passive continental margins can include mar

gins where siliciclastic sediments drape over basement ridges, folds, or faults (Fig.

10.4 A, B, C); margins with a carbonate bank or platform (Fig. 10.40}, and margins

dominated by salt tectonics (flowage of salt to produce salt domes and diapirs;

Fig. 10.4F). More than one of these passive-margin types may be present within a

given geographic area. Active continental margins may be characterized by the

psence of a fore-arc region only or by both fore-arc and back-arc regions, as, for

example, the Japan margin (Fig. 10.13). Sedimentation can take place in bo back

a and fore-arc basins, on back-arc and fore-arc slopes, and in the fore-arc trench.

Continental slopes may have a smooth, slightly convex surface morphology,

such as that found on passive siliciclastic margins (e.g., Fig. 10.4A) or they may be

irregular on a small to very large scale. Active-margin slopes tend to be particular

ly irregular. For example, the Pacific slope off Japan, which descends to a depth of

about 7000 m into the Japan Trench, is characterized by structural terraces and

basins together with anticlinal welts and fault-bounded ridges arranged in an ech

elon pattern roughly parallel to the Japan coast (Boggs, 1984). These ridges and

folds form prominent structural "dams" behind which sediments are ponded. In

general, structural barriers on highly irregular slopes can hibit movement of

bottom sediment across the slope and create catchment basins for sediment.

Figure 10.12

Principal elements of the

continental margin. [After

Drake, C. L., and C. A. Burk,

1974, Geological signifi

cance of continental mar

gins, in Burk, C. A., and C.

L. Drake (eds.), The geology

of continental margins, Fig.

9, p. 8, reprinted by permis

sion of Springer-Verlag, Hei

delberg.]

Figure 10.13

JAPAN BASIN

\

YAMATO

BASIN

\

•

HON

SHU

(

J

apan

)

Subduction Complex __

Trench

Schematic representation of an ac

tive continental margin (Japan),

showing both the fore-arc and

back-arc characteristics of the mar

gin. [From Boggs, S., Jr., 1984,

Quaternary sedimentation in the

Japan arc-trench system: Geol. Soc.

America Bull., v. 95, Fig. 2, p. 670.]

352

Chapter lO I Siliciclastic Marine Environments

Modem continental slopes are gashed to various degrees by submarine

canyons oriented approximately normal to the shelf break (see Fig. 10.16, 10.19),

which provide accessways for turbidity currents moving across the slope. Most sub

marine canyons have their heads near the slope break and do not cross the shelf;

however, a few major canyons on modem shelves extend onto the shelf and head up

ve close to shore. Some large canyons also extend seaward beyond the base of the

slope to form deep-sea annels that may meander over the nearly flat ocean floor

for hundreds of lometers. The Toyama Deep a Channel in the Japan a, for ex

ample, winds its way across the seaoor from the mouth of the Toyama Trough for

approximately 500 before emptying onto the Japan a abyssal plain.

The origin of submarine canyons has been debated since the early part of the

twentieth century (Pickering, Hiscott, and Hein, 1989, p. 134-136). Although

downcutting by rivers that extended across the shelf during periods of lowered

sea level may have initiated the formation of some canyons on the shelf, turbidity

currents are the main agents of canyon cutting on the slope and deeper seaoor.

Canyon development may be initiated by local slope failure (slumping), followed

by headward growth of erosional scars. Turbidity currents are erosive in their ini

tial stages and thus can deepen and lengthen the incipient canyons over time,

aided by further slumping on the upper part of the slope. The locations and

shapes of some submarine canyons may have been influenced by the presence of

faults and folds (Green, Clarke, and Kennedy, 1991 ).

Continental Rise and Deep Ocean Basin

The continental rise and deep ocean basin encompass that part of the ocean lying

below the base of the continental slope. To gether, they make up about 80 percent

of the total ocean seafloor. The deeper part of the ocean seaward of the continental

slope is divided into two principal physiographic components: the deep ocean

floor, which is characterized by the presence of abyssal plains, abyssal hills (vol

canic hills <1 km high), and seamounts (volcanic peaks > 1 high); and oceanic

ridges. Off passive contental margins, a continental rise (Fig. 10.1) is present at

the base of the slope. The continental rise is a gently sloping surface that leads

gradually onto the deep ocean oor and is built in part from submarine fans ex

tending seaward from the foot of the slope. It commonly has little relief other than

that resulting from incised submarine canyons and protruding seamounts. Conti

nental rises are generally absent on convergent or active margins whe subduc

tion is taking place, such as along much of the Pacific margin. margins of this

type, a long, arcuate deep-sea trench commonly lies at

the foot of the continental

slope, and the rise is absent. Trenches in less active subduction zones, such as

along the Oregon-Washington coast, may be filled with sediment. Abyssal plains

are extensive, nearly flat areas punctuated here and there by seamounts. Some

abyssal

plains are also cut by deep-sea channels, as mentioned. Mid-ocean ridges

extend across some 60,000 km of the modern ocean and overall make up about

30-35 percent of the area of the ocean. Mid-ocean ridges are particularly promi

nent in the Atlantic, where they rise about 2.5 above the abyssal plains on ei

ther side. Rocks on these ridges are predominantly volcanic; the ridges are cut by

numerous transverse fractu zones along which significant lateral displacements

may be apparent. Ridges play a crucial role in the seafloor spreading process, but

they are not particularly active areas of sedimentaon. They do have a very im

portant effect on circulation of deep bottom currents in the ocean and thus have an

indirect effect on sedimentation in the deep ocean.

nanspo and Depositional Processes to and within Deep Wa ter

Most

sedimt deposited deeper water, other than wind-blown sediment, orig

inates on the shelf and must make its way across the shelf (Fig. 10.5, 10.14) to get

t

0

E

E

c

0

�

E

:

�

PROCESSES

Wind

Sediment plume

Floating ice

Rock fall

Creep

Slide

Slump

Debris flow

Grain flow

Fluidized flow

L

iquefied flow

Tu rbidity current

(high/low density)

Internal tides and

waves

Canyon currents

Bottom (contour)

currents

Deep surface

currents

Surface currents

and pelagic settling

Flocculation

Pelletization

Chemogenic

processes

(authigenesis and

dissolution)

CHARACTERISTICS

10.3 e Oceanic (Deep-Water) Environment

353

DEPOSITS

Pelagic mud

Hemipelagic mud

Glaciomarine

(dropstones)

Olistolith

Avalanche deposit

Creep deposit

Slide

Slump

Debrite

Grain flow deposit

Fluidized flow deposit

Liquefied flow deposit

Turbidite (coarse,

medium, and

fine-grained)

Normal current deposit

Contourite

Pelagic ooze

Hemipelagic mud

FeMn nodules, lami

nation, pavements,

and umbers

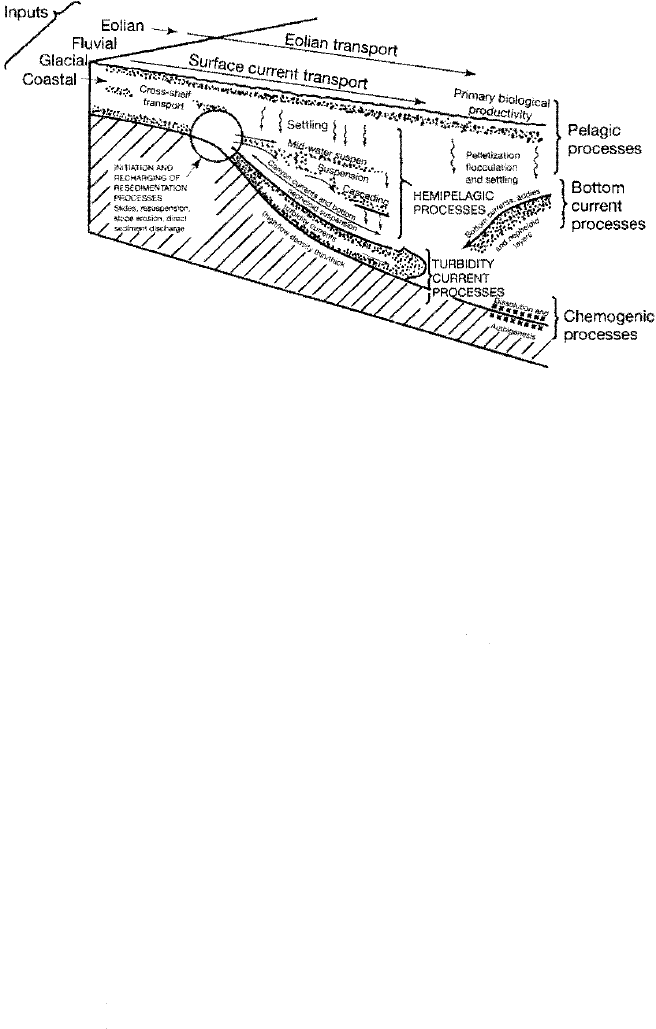

Figure 10.14

The various kinds of processes that operate in

the deep sea to transport and deposit sedi

ments. (After Stow, D. A. V., 1994, Deep sea

processes of sediment transport and deposi

tion, in Pye, K. (ed.), Sediment transport and

depositional processes, Blackwell Scientific Pub

lications, Oxford, Fig. 8.2, p. 261, reproduced

by permission.]

to deeper water environments. Across-shelf sediment movement (discussed under

shelf transport in preceding sections) includes transport of coarser sediment by

turbidity currents and seaward advection of fine sediment by sediment plumes

and nepheloid flows. A variety of processes is capable of transporting and de

positing sediment within the deep ocean, such as wind transport from continents,

airfall and submarine settling of pyroclastic particles generated by explosive vol

canism within and outside ocean basins, sediment plumes, floating ice, mass-ow

processes, various kinds of bottom currents, surface currents, and pelagic settling

(e.g., Stow, 1994). These processes are summarized in Figure 10.14. The locations

within the deep ocean where the various processes operate are summarized more

graphically in Figure 10.15.

Sediment Plumes, Wind Transport, Ice Raing, Nepheloid Tr ansport

Where continental shelves are narrow, freshwater surface plumes carrying fine

sedimt across the shelf (Fig. 10.5) can move considerable distances into deeper

water, possibly as far as 100 km offshore (Reineck and Singh, 1980), before mixing

354 Chapter 10 I Siliciclastic Marine Environments

Figure 10.15

Schematic representation of principal processes responsible for transport and deposition

of sediments to the deep ocea n. Note that most of the processes deposit fine sediment;

however, glacial (floating ice), turbidity current, and resedimentation processes can move

both coarse and fine sediment. Chemogenic refers to minor processes that are largely

chemical in nature. [After Stow, D. A V., H. G. Reading, and ). D. Collinson, 1996, Deep

seas, in Reading, H. G. (ed.), Sedimentary environments: Processes, facies and stratigra

phy, Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, p. 39553, reproduced by permission.]

and flocculation cause clay particles to settle. Winds blowing over continents, par

ticularly desert areas, can also transport fine suspended dust particles seaward,

where they settle out over the ocean hundreds of kilometers from shore. fact,

wind transport may be the primary mechanism by which day-size siliciclastic

sediment is transported to the distal part of the deep ocean.

During glacial episodes of the Pleistocene when sea levels were low and

many land areas were covered by ice, rafting of sediment of all sizes into deeper

water by icebergs was a parcularly important transport process. Ice transport is

still going on today on a more limited scale at high latitudes in the Arctic and

Antarctic regions (e.g., Anderson and Ashle 1991; Dowdeswell and Scourse,

1990; Kempema, Reimnitz, and Barnes, 1988). Melting of the floating ice dumps

sediments of mixed sizes, commonly referred to as glacial-marine sediment

(Chapter 9), onto the shelf and the deep ocean floor. The overall quantitative sig

nificance of iceberg transport into deep water through geologic time has probably

not been significant, but locally and at certain times it may have been important.

Fe sediment resuspended by storms on the outer shelf can move off the

shelf and down the slope in near-bottom nepheloid suspension. Less-dense sus

pensions may move seaward along density interfaces as midwater suspensions

that gradually settle to the bottom (Fig. 10.15). Fine sediment may also be injected

into the water column by turbidity flows moving downslope. Nepheloid flows are

reported to extend seaward for hundreds of kilometers and to water depths of

6000 m or more. Deep bottom currents ( be discussed) may aid in resuspending

sediment into nepheloid layers.

Cuents in Canyons

Tidal curren measured in submarine canyons at depths exceeding 1000 m may be

capable of transporting silt and fine sand (Shepard, 1979; Pickering, Hiscott, and

Hein, 1989, p. 143). Two types of currents have been detected in submarine valleys:

10.3 The Oceanic (Deep-Water) Environment

355

ordinary tidal currents that rarely exceed 50 cm/s and that flow alternately up

and down the valley in response to tidal reversal, and occasional surges of strong

downcurrent flow with velocities up to 100 cm/s. Shepard (1979) interprets the

surges as low-velocity turbidity currents. There are few data as yet to support the

quantitative importance of net down-canyon transport owing to tidal currents;

however, surge currents of the magnitude measured by Shepard are certainly ca-

pable of transporting ne sediment seaward. Together, these currents probably

help to winnow canyon deposits and keep them free from fine sediment.

Contour Currents

Density differences in surface ocean water caused by temperature or salinity vari

ations create vertical circulation of water masses in the ocean commonly referred

to as thermohaline circulation. Circulation is initiated primarily at high latitudes

as cold surface waters sink toward the bottom, forming deep-water masses that

flow along the ocean floor as bottom currents. The path of these bottom currents is

influenced by the position of oceanic ridges and rises and other topographic fea

tures such as narrow passages through fracture zones. Owing to density stratica

tion of ocean water, bottom currents adjacent to continental margins tend to flow

parallel to depth contours or isobaths and thus are often called contour currents.

The movement of these currents is also affected by the Coriolis force, which like

wise tends to deflect them (left in the Southern Hemisphere and right in the

Northe Hemisphere) into paths parallel to depth contours; thus, they are some

times also called geostrophic contour currents.

In the modem ocean, Antarctic bottom water runs down the continental

slope, circulates eastward around the Antarcc continent possibly several mes,

and then flows northward into the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific ocea (Stow, 1994).

In e North Atlantic, deep bottom water flows south out of the Norwegian

Greenland seas, Labrador Sea, and other parts of the North Atlantic. Interaction of

ese deep-water masses creates a highly complex ocean circulation system.

Because contour currents are best developed in areas of steep topography

where the bottom topography extends throu the greatest thickness of stratified

water column (Kennett, 1982), they are particularly important on the continental

slope and rise. Photographs of the deep seafloor have revealed current ripples in

some areas and suspended sediment clouds and seafloor erosional features in oth

ers, both of which suggest that some contour currents can achieve velocies on or

near the seafloor great enough to erode the seabed and transport sediment. Evi

dence is now available (e.g., Hollister and Nowell, 1991) which suggests that the

speed of these bottom currents may be accelerated in some parts of the ocean to

velocities on the order of em/ s, perhaps because of the superimposed influence

of large-scale, wind-driven circulation at the ocean's surface. That is, eddy kinec

ergy may be transmitted from the surface of the ocean to the deep seafloor. In

tsification may also occur where the Coriolis Force causes deep flows to bank

up against the continental slope on the westem margins of ocean basins, where it

is unable to move upslope against gravity and thus becomes restricted and inten

sified (Stow, 1994). Where bottom currents are intensified, resulting motions near

e seafloor are so energetic that they have been referred to as "abyssal storms" or

"bthic storms" (Hollister and Nowell, 1991), particularly because huge amounts

of fine sediments are stirred up and transported by these energetic pulses. Con

tour currents are believed to have had a particularly important role in shaping and

modifying continental rises, such as those off the eastern coast of North America.

Pelac Rain

Calcareous- and siliceous-shelled planktonic organisms settle through the ocean

water column to the seafloor upon death, a process called pelagic rain or pelagic