Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

434 TWO EPILOGUES

these, most famously a copy of Cicero’s Letters to Atticus in a monastic library in

Verona. Scribes and scholars diligently circulated these new and improved works.

Apart from the texts’ intrinsic value as literature or philosophy, the people of

the early Renaissance valued them as practical guides to living. After all, if some-

thing is true it is worthy not only of study but of practical application. This atti-

tude, too, was not entirely new. When medieval scholars rediscovered the Corpus

juris civilis, they were not slow in recognizing that it could be put to actual use

in administering twelfth-century life. Similarly with the new texts rediscovered in

the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Since the bulk of them had been written in

and for small urban republics, and since they were found by figures in and of the

same sort of societies, why not encourage their direct application? Hence Cicero’s

notions of the role of the citizen in the republican state, of the power and limits

of the law, and of the sense of civic responsibility all struck a chord that people

increasingly strove to follow. Poems like Virgil’s Eclogues, with their rhapsodic

praises of the glories of rural landscapes and rustic pleasures, helped to encourage

artists to paint stirring images, increasingly realistic or representational, of the

beauties of nature. Roman interest in biography, in the portrayal of the life histories

of individuals, inspired a revival of that genre.

4

Petrarca famously described the

difference between medieval scholasticism and Renaissance humanism precisely

in terms of potency. Scholastic philosophy, he argued, could define a virtue like

goodness but was incapable of inspiring anyone to become good, whereas the

very greatness of humanistic study was in its capacity to inflame the heart, to

make us crave virtue. It is more important to want to pursue truth than it is to

define truth—in other words, to be an impassioned traveler than to be a sedentary

possessor of a brilliant map.

By the end of the sixteenth century, the west had recovered virtually the entire

classical literary canon as we know it. It was a remarkable achievement. Armed

with critical skills to match their convictions, Renaissance scholars had scoured

Europe’s libraries, sifted through thousands of manuscripts, rescued scores of un-

known works from oblivion, and produced dramatically improved texts of the

ancient world’s greatest authors. (One fellow, Giovanni Aurispa [d. 1459], traveled

east to Constantinople in the years prior to the Turkish siege and came back with

nearly 250 manuscripts that might otherwise have gone up in flames.) Moreover,

scholars made these works available to other scholars on an unprecedented scale:

Hundreds of copyists were employed to get the texts in circulation; the city of

Florence in the early fifteenth century established the first lending library; and of

course the invention of the printing press allowed books to pour over Europe like

a tide. The most celebrated of humanist publishers was Aldus Manutius (d. 1515),

who set up his printing shop in Venice in 1493 and managed to produce editions

of well over a hundred separate classical texts before his death.

Renaissance classicism is perhaps the least innovative aspect of humanist life,

the aspect most directly linkable to its medieval past. But its accomplishments

were considerable, not only in expanding the literary canon but in expanding the

western heart and urging it on to new challenges. The passion with which scholars

pursued their classical quest had its negative consequences, most notably in the

artificial manipulations of a still-living Latinity, but on the whole the extraordinary

expansion of classical learning was one of the Renaissance world’s (and the me-

dieval world’s) greatest legacies.

4. Not to mention that of autobiography: The autobiography of a Renaissance adventurer like Benven-

uto Cellini is not to be missed.

THE RENAISSANCE IN MEDIEVAL CONTEXT 435

T

HE

R

EJECTION OF THE

M

IDDLE

A

GES

While the early Renaissance had much in common with the medieval period, it

also loudly rejected it. Perhaps the very loudness of that rejection should make us

wary of its genuineness, for people are seldom so absolutely insistent that they

have nothing at all to do with a given thing as when they in fact do. Nevertheless,

as early as Petrarca, the leading figures in the new humanist movement were

openly declaring their total opposition to all things medieval. The medieval

Church was, it went almost without saying, a horror show of corrupt politics and

dry-as-dust scholastic hairsplitting. Medieval Latin was a brutish, adulterated lan-

guage twisted and mangled beyond recognition from the pure elegance of writers

like Cicero and Tacitus; medieval architecture (by which the humanists meant

chiefly Gothic architecture) was a nightmare of spires, pointy arches, sculptural

excess, and tacky coloration; medieval philosophy was a charade of mind-

numbing abstraction and foolhardy systematization; medieval politics (by which

they meant feudal monarchy, for the most part) was mere barbarism by another

name, savage tribalism dressed up in robes and crowns. The grand role assumed

by the humanists was to configure a new path. The fifteenth-century philosopher

Marsilio Ficino (d. 1499) expressed admiration for his aggressively non-medieval

age: “This century has been a Golden Age, one that has restored to light all the

liberal arts—grammar, poetry, rhetoric, painting, sculpture, architecture, and mu-

sic—arts that were virtually extinct.”

Of course, the arts were hardly extinct in the Middle Ages, but they were

certainly devoted to somewhat different aims. Consider architecture, for example.

Ever since the rise of the great castles and cathedrals of the late twelfth and thir-

teenth centuries, architecture had been one of the dominant arts in Europe. In the

Middle Ages it was also an overwhelmingly public art form: A cathedral repre-

sented far more than a single building or plan designed by a single architect; it

was a public statement of faith, a commitment of hundreds of thousands of labor

hours and the equivalent of hundreds of millions of dollars over several genera-

tions (and sometimes over as many as two centuries) in pursuit of a spiritual

vision. It was an exaltation in stone. The first direct and overt challenge to Gothic

architectural style came with Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), who completed the

cathedral of Florence around 1420. He did away with Gothic towers and pointed

arches, stripped away unnecessary statuary, and based his overall design on sim-

ple geometrical shapes (circular windows set within square panels that are them-

selves part of a clearly delineated rectangular wall plane, for example). The overall

effect is of a simpler and more harmonious gracefulness than a Gothic cathedral,

and its use of domes and columns consciously evokes the architectural styles of

the Roman world. From Brunelleschi’s revolt on, Renaissance architect never

looked back. Anything that was not, for a time, in conscious revolt against the

High Gothic style and the world that had created it was deemed artistically and

intellectually backward. Medieval had become a dirty word.

For all its positive qualities, early humanism had its problems. One was its

obvious elitism. The humanists did not want to speak like common people, think

like common people, or believe what common people believed. Petrarca went so

far as to criticize his beloved Cicero for having ventured into the messy world of

politics instead of staying at home to breathe the cleaner air of philosophy in his

private study, far from the sullying crowd; he also heaped scorn on the intrigues

in the papal court at Avignon, but the mess never bothered him enough to make

him leave or renounce his annuities. Giovanni Boccaccio magnificently sang the

436 TWO EPILOGUES

praises of the everyday in his Decameron, but he wrote his stories while living in

the comfortable quarters of the Neapolitan royal palace surrounded by aristocratic

admirers and aesthetic neophytes. Not until the end of the fourteenth century,

with figures like Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406) in Florence, did leading humanists

become directly involved in administering the day-to-day life of their communi-

ties.

5

The humanists, in other words, were guilty of celebrating humanism more

than humans.

By 1400, then, Europe was still recognizably medieval in its main outlines, even

though there was a powerful and fascinating new set of ideas and values in the

air. The Church, bedraggled though it was, was still the dominant institution in

European life. The political makeup of the continent was still mostly what it had

been in the thirteenth century. Philosophical and scientific thinking were still

shaped by the knowledge of the ancients. But important, even transformative,

shifts were also underway. A profound sense of skepticism and of the world’s

jumbled nature was widespread; the economic center of European life had begun

to shift to the Atlantic seaboard, although it would take another hundred years

for that shift to become fully tangible; an acceptance of the idea that one could

approach God and know Him other than through the Church and its sacraments

was rapidly gaining ground. The Renaissance that began in the midst of the dra-

mas of the fourteenth century was an inspired and inspiring response to great

troubles and doubts, one that quickly developed into something quite different

and wonderful. For all its glory, though, the Renaissance owed much to the me-

dieval world from which it sprang.

S

UGGESTED

R

EADING

Texts

Cellini, Benvenuto. Autobiography.

Petrarca, Francesco. Lyrics.

Salutati, Coluccio. Autobiography.

Source Anthologies

Cohen, Timothy V., and Elizabeth S. Cohen. Words and Deeds in Renaissance Rome: Trials before the

Papal Magistrates (1993).

The Portable Renaissance Reader.

Studies

Bolzoni, Lina. The Gallery of Memory: Literary and Iconographic Models in the Age of the Printing Press

(2001).

Grendler, Paul F. Schooling in Renaissance Italy: Literacy and Learning, 1300–1600 (1991).

5. Salutati wrote, “The people of Florence are the defenders of the liberty of all people everywhere,”

but he never blinked an eye when Florence seized an advantage and subjugated any of her neighbors.

By Salutati’s death, Florence had even brought Pisa to heel and had become the third major power in

northern Italy.

THE RENAISSANCE IN MEDIEVAL CONTEXT 437

Haas, Louis. The Renaissance Man and His Children: Childbirth and Early Childhood in Florence, 1300–

1600 (1998).

Hamilton, Alastair. Heresy and Mysticism in Sixteenth-Century Spain: The Alumbrados (1992).

Hollingsworth, Mary. Patronage in Renaissance Italy: From 1400 to the Sixteenth Century (1996).

King, Margaret L. Women of the Renaissance (1991).

———. Venetian Humanism in an Age of Patrician Dominance (1986).

Martines, Lauro. Strong Words: Writing and Social Strain in the Italian Renaissance (2001).

Mazzotta, Giuseppe. Cosmopoeiesis: The Renaissance Experiment (2001).

Ozment, Steven. The Age of Reform, 1250–1550 (1980).

Rabil, Albert. Renaissance Humanism: Foundations, Forms, and Legacy (1988).

Shuger, Deborah Kuller. Habits of Thought in the English Renaissance: Religion, Politics, and the Dom-

inant Culture (1997).

Stinger, Charles. The Renaissance in Rome (1998).

Wilkins, Ernest Hatch. Life of Petrarch (1961).

438

A

PPENDIXES

8

A

PPENDIX

A. The Medieval Popes

The table below lists the popes in chronological order, gives the dates of their

pontificates, indicates their vernacular names and ethnicity, and records the eccle-

siastical position held by each individual prior to assuming the Holy See. The

dates of pontificates are subject to much scholarly revision; I have adhered to the

dates published by the Vatican’s own Anuario pontificio.

Pope Papacy Birth Name Nationality Previous Ecclesiastical Rank

St. Peter d. 64 Simon Galilean fisherman

St. Linus 67–76

St. Anacletus 76–88 Greek

St. Clement I 88–97

St. Evaristus 97–105 Greek

St. Alexander I 105–115 Roman

St. Sixtus 115–125

St. Telesphorus 125–136 Greek

St. Hyginus 136–140 Greek

St. Pius I 140–155

St. Anicetus 155–166 Syrian

St. Soter 166–175

St. Eleutherius 175–189 Greek deacon

St. Victor I 189–198 African

St. Zephrynus 199–217

St. Calixtus I 217–222 archdeacon

St. Urban I 222–230

St. Pontian 230–235

St. Anterus 235–236 Greek

St. Fabian 236–250

St. Cornelius 251–253

St. Lucius I 253–254

St. Stephen I 254–257

St. Sixtus II 257–258 Greek

St. Dionysius 260–268 Roman priest

St. Felix I 269–274

St. Eutychian 275–283

St. Gaius 283–296

St. Marcellinus 296–304

St. Marcellus I 308–309

St. Eusebius 309–310 Greek

St. Melchiades 311–314 African?

St. Sylvester I 314–335

APPENDIXES 439

Pope Papacy Birth Name Nationality Previous Ecclesiastical Rank

St. Mark 336

St. Julius I 337–352

Liberius 352–366

St. Damasus 366–384 Roman deacon

St. Siricus 384–399

St. Anastasius 399–401 Roman

St. Innocent I 401–417 Roman

St. Zosimus 417–418 Greek priest

St. Boniface I 418–422 Roman priest

St. Celestine I 422–432 Roman archdeacon

St. Sixtus III 432–440

St. Leo I the Great 440–461 deacon

St. Hilarus 461–468 archdeacon

St. Simplicius 468–483

St. Felix III (II) 483–492 Roman

St. Gelasian 492–496 African

Anastasius II 496–498 Roman

St. Symmachus 498–514 Roman deacon

St. Hormisdas 514–523

St. John I 523–526

St. Felix IV (III) 526–530 Roman card.-priest

Boniface II 530–532 German archdeacon

John II

a

533–535 Mercurius priest

St. Agapitus I 535–536 deacon

St. Silverius 536–537 subdeacon

Vigilius 537–555 Roman deacon

Pelagius I 556–561 deacon

John III 561–574 Catalinus deacon

Benedict I 575–579 Roman deacon

Pelagius II 579–590 German deacon

St. Gregory I “the

Great”

b

590–604 Roman monk

Sabinian 604–606 deacon

Boniface III 607 Roman deacon

St. Boniface IV 608–615 Roman monk

St. Adeodatus I 615–618 priest

Boniface V 619–625 Neapolitan priest

Honorius I 625–638

Severinus 640

John IV 640–642 Croatian

Theodore I 642–649 Greek

St. Martin I 649–655

St. Eugenius I 654–657 Roman priest

St. Vitalian 657–672

Adeodatus II 672–676 monk

Donus 676–678 Roman

St. Agatho 678–681 Greek-

Sicilian

monk

St. Leo II 682–683 Sicilian

St. Benedict II 684–685 Roman

John V 685–686 Syrian archdeacon

Conon 686–687 Thracian priest

St. Sergius I 687–701 Syrian

John VI 701–705 Greek

440 APPENDIXES

Pope Papacy Birth Name Nationality Previous Ecclesiastical Rank

John VII 705–707 Greek

Sisinnius 708 Syrian

Constantine 708–715 Syrian

St. Gregory II 715–731 Roman deacon

St. Gregory III 731–741 Syrian

St. Zacharias 741–752 Greek

Stephen II (III) 752–757 Roman priest

St. Paul I 757–767 Roman deacon

Stephen III (IV) 768–772 Sicilian

Hadrian I 772–795 Roman deacon

St. Leo III 795–816

Stephen IV (V) 816–817

St. Paschal 817–824 abbot of St. Stephen’s

Eugenius II 824–827 Roman archpriest

Valentine 827

Gregory IV 827–844 Roman card.-priest

Sergius II 844–847 Roman card.-priest

St. Leo IV 847–855 Roman card.-priest

Benedict III 855–858 Roman card.-priest

St. Nicholas I 858–867

Hadrian II 867–872 Roman card.-priest

John VIII 872–882 Roman archdeacon

Marinus I

c

882–884 Roman card.-bishop of Cerveteri

St. Hadrian III 884–885 Roman

Stephen V (VI) 885–891 Roman card.-priest

Formosus 891–896 Roman card.-bishop of Porto

Boniface VI 896 Roman priest

Stephen VI (VII) 896–897 Roman card.-bishop of Anagni

Romanus 897 Roman

Theodore II 897 Roman

John IX 898–900 Roman abbot

Benedict IV 900–903 Roman

Leo V 903 priest

Sergius III 904–911 Roman deacon

Anastasius III 911–913 Roman

Landus 913–914

John X 914–928 archbishop of Ravenna

Leo VI 928 priest

Stephen VII (VIII) 928–931

John XI 931–935 Roman

Leo VII 936–939 monk

Stephen VIII (IX) 939–942

Marinus II 942–946

Agapitus II 946–955 Roman

John XII

d

955–964 Octavianus Roman layman

Leo VIII 963–965 Roman layman

Benedict V 964 Roman card.-deacon

John XIII 965–972 Umbrian bishop of Narnia

Benedict VI 973–974 Roman card.-priest

Benedict VII 974–983 Roman bishop of Sutri

John XIV 983–984 Pietro Canepanova bishop of Pavia

John XV 985–996 Roman card.-priest

Gregory V 996–999 Saxon

APPENDIXES 441

Pope Papacy Birth Name Nationality Previous Ecclesiastical Rank

Sylvester II 999–1003 Gerbert d’Aurillac French archbishop of Ravenna

John XVII 1003 Giovanni Sicco Roman layman

John XVIII 1004–1009 card.-priest

Sergius IV 1009–1012 Pietro Roman bishop of Albano

Benedict VIII 1012–1024 Theophylact Roman layman

John XIX 1024–1032 Romanus Roman layman

Benedict IX 1032–1048 Theophylact Roman layman

Sylvester III 1045 Giovanni Roman bishop of Sabina

Gregory VI 1045–1046 Giovanni

Graziano

Roman archpriest

Clement II 1046–1047 Suitger Saxon bishop of Bamberg

Damasus II 1048 Poppo Bavarian bishop of Brixen

St. Leo IX 1049–1054 Bruno von

Egisheim

Alsatian bishop of Toul

Victor II 1055–1057 Gebhart Swabian bishop of Eichsta¨tt

Stephen IX (X) 1057–1058 Fre´de´ric de

Lorraine

French abbot of Monte Cassino

Nicholas II 1059–1061 Gerard French bishop of Florence

Alexander II 1061–1073 Anselmo di Lucca Milanese bishop of Lucca

St. Gregory VII 1073–1085 Hildebrand card.-archdeacon

Bl. Victor III 1086–1087 Dauferio

[Desiderius]

Beneventan abbot of Monte Cassino

Bl. Urban II 1088–1099 Eude de Chaˆtillon French card.-bishop of Ostia

Paschal II 1099–1118 Rainerius abbot of S. Paolo

Gelasius II 1118–1119 Giovanni [] Amalfitan archdeacon

Calixtus III 1119–1124 Guy de

Bourgogne

French archbishop of Vienne

Honorius II 1124–1130 Lamberto card.-bishop of Ostia

Innocent II 1130–1143 Gregorio

Papareschi

card.-deacon

Celestine II 1143–1144 Guido del Castello Tuscan card.-priest

Lucius II 1144–1145 Gerardo

Caccianemici

Roman card.-priest

Bl. Eugenius III 1145–1153 Bernardo Paganelli Pisan abbot

Anastasius IV 1153–1154 Corrado Suburra card.-bishop of S. Sabina

Hadrian IV 1154–1159 Nicholas

Breakspear

English card.-bishop of Albano

Alexander III 1159–1181 Orlando

Bandinelli

Sienese card.-priest

Lucius III 1181–1185 Umbaldo

Allucingoli

card.-bishop of Ostia

Urban III 1185–1187 Umberto Crivelli Milanese archbishop of Milan

Gregory VIII 1187 Alberto Morra card.-deacon

Clement III 1187–1191 Paolo Scolari Roman card.-bishop of Palestrina

Celestine III 1191–1198 Giacinto Bobone Roman card.-deacon

Innocent III 1198–1216 Lothario dei Segni Roman card.-deacon

Honorius III 1216–1227 Cencio Savelli Roman card.-priest

Gregory IX 1227–1241 Ugolino dei Segni Roman card.-bishop of Ostia

Celestine IV 1241 Goffredo

Castiglione

Milanese card.-bishop of Sabina

Innocent IV 1243–1254 Sinibaldo Fieschi Genoese card.-priest

Alexander IV 1254–1261 Rinaldo Conti card.-bishop of Ostia

Urban IV 1261–1264 Jacques Pantale´on French patriarch of Jerusalem

442 APPENDIXES

Pope Papacy Birth Name Nationality Previous Ecclesiastical Rank

Bl. Gregory X 1272–1276 Teobaldo Visconti Milanese card.-archdeacon

Bl. Innocent V 1276 Pierre Tarantaise French card.-bishop of Ostia (O.P.)

Hadrian V 1276 Ottobuono Fieschi Genoese card.-deacon

John XXI 1276–1277 Pedro Julia˜o Portuguese card.-bishop of Tusculum

Nicholas III 1277–1280 Giovanni Orsini Roman archpriest

Martin IV 1281–1285 Simon de Brie French card.-priest

Honorius IV 1285–1287 Giacomo Savelli Roman card.-deacon

Nicholas IV 1288–1292 Girolamo Maschi Abruzzese card.-bishop of Palestrina

(O.F.M.)

St. Celestine V 1294 Pietro Murrone Neapolitan hermit monk

Boniface VIII 1295–1303 Benedetto Gaetano Tusculan card.-priest

Bl. Benedict XI 1303–1304 Niccolo` Boccasini card.-bishop of Ostia (Dominican

Minister General)

Clement V 1305–1314 Bertrand de Got Gascon archbishop of Bordeaux

John XXII 1316–1334 Jacques Due`se de

Cahors

French card.-bishop of Porto

Benedict XII 1335–1342 Jacques Fournier French card.-bishop of Mirepoix

Clement VI 1342–1352 Pierre Roger French archbishop of Rouen

Innocent VI 1352–1362 Etienne Aubert French card.-bishop of Ostia

Bl. Urban V 1362–1370 Guillaume

Grimard

French abbot of S. Victoire (Marseilles)

Gregory XI 1370–1378 Pierre Roger de

Beaufort

French card.-deacon

Urban VI 1378–1389 Bartolomeo

Prignano

Apulian archbishop of Bari

Boniface IX 1389–1404 Pietro Tornacelli Neapolitan card.-priest

Innocent VII 1404–1406 Cosimo dei

Migliorati

archbishop of Bologna

Gregory XII 1406–1415 Angelo Correro Roman card.-priest

Martin V 1417–1431 Odo Colonna Roman card.-deacon

Eugenius IV 1431–1447 Gabriele

Condulmaro

Venetian card.-priest

Nicholas V 1447–1455 Tommaso

Parentucelli

Bolognese archbishop of Bologna

a

John II (533–535) was the first pope to take a new name upon election to the Holy See. He did

so presumably because of the pagan connotations of his birth name. The taking of a new pontifical

name did not become the norm until the turn of the first millennium a.d. Prior to the year 1000,

only four popes (John II, John III, John XII, and John XIV) did so.

b

Gregory I (590–604) was the first monk to become pope. Innocent V (1276) was the first Do-

minican pope, and Nicholas IV (1288–1292) was the first Franciscan.

c

Marinus I (882–884) was the first bishop to become pope. Canon XV of the Council of Nicaea

(325) forbade the translation of bishops from one see to another, and since the office of the papacy

was inextricably linked with the episcopacy of Rome, no bishop of another city could be consid-

ered a candidate. A handful of exceptions were made in the difficult post-Carolingian period (of

which Marinus was the first); but the Nicaean ban was gradually set aside during the Gregorian

Reform, paving the way for the virtual monopoly on the papacy held by bishops since the elev-

enth century.

d

John XII (955–964) was the first layman elected to the papacy.

APPENDIXES 443

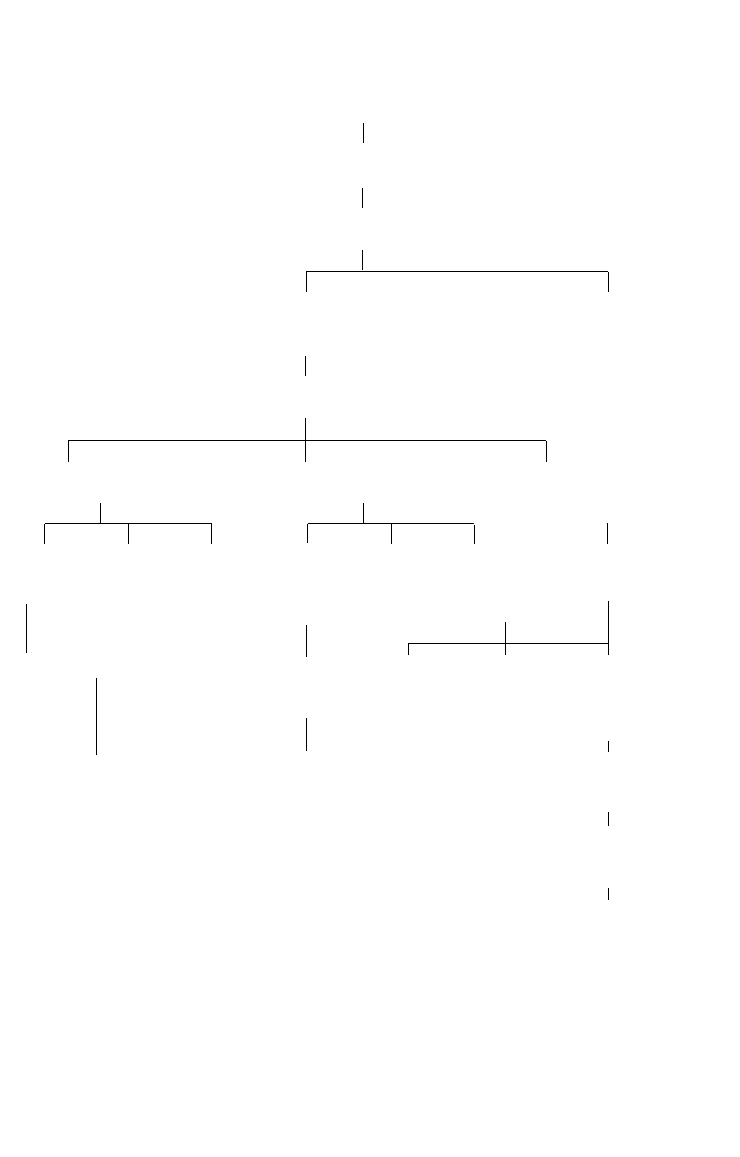

A

PPENDIX

B. The Carolingians

Pepin of Heristal

d. 714

Charles Martel

d. 741

Louis the Pious

Emp. 814–840

Louis the German

K. of East Franks, 840–876

Louis the Child

K. of East Franks

899–911

Charles the Bald

K. of West Franks, 840–877

Emp. 875–877

Lothar

Emp. 840–855

Carloman

d. 771

Charlemagne

K. of the Franks, 768–814

Emp. 800–814

Ermengarde = Boso

K. of

Provence

879–887

Arnulf

K. of

East Franks

Louis the Blind

K. of Provence

Louis the Stammerer

K. of West Franks

877–879

Louis II

Emp.

855–875

Charles

K. of

Provence

855–863

Louis V

K. of West Franks

986–987

Lothar

K. of West Franks

954–986

Louis IV

K. of West Franks

936–954

Lothar II

K. of

Lotharingia

855–869

Pepin the Short

K. of the Franks, 751–768

Carloman

K. of

Bavaria

876–880

Louis

K. of

Saxony

876–882

Charles the Fat

K. of Swabia

876–884

Emp. 884–887

Louis III

K. of West

Franks,

879–882

Carloman

K. of West

Franks,

879–884

Charles the Simple

K. of West

Franks

898–922