Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

384 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

arrows they launched could pierce a suit of armor at a distance of two hundred

yards. Accuracy at such a distance was poor but hardly mattered, since one could

produce more than a hundred such bows and equip the men to shoot them for

less cost than that of the single mounted knight they aimed at. Continuous volleys

of hundreds of arrows could cover a large area and cut down considerable num-

bers of mounted knights long before they could arrive at the battlefield’s center.

Those knights who survived the longbow volleys then had to contend with

the crossbows. These were fearsome weapons, about the length of a modern

sawed-off shotgun, that shot fat metal bolts called quarrels. Engaging the firing

mechanism required great strength; with the first crossbows a bowsman had to

bend at the waist, place the front end of the crossbow on the ground, step into a

stirrup at the tip, attach the drawstring to a hook on his belt, and slowly straighten

himself and arch his back until the drawstring finally engaged the trigger. Later a

ratcheted iron gear, turned by a thick crank, drew the bowstring and provided the

impetus for the bolt’s flight. Like the longbow, the crossbow could shoot its mis-

siles through a knight’s suit of armor and could in fact pierce and shatter the

thickest human bones that lay behind it. The crossbow was the first weapon in

Western history to be officially condemned by the Catholic Church for its awesome

destructive force—the first attempt to stop the arms race. What horrified people

especially was not the sheer deadliness of these weapons but the fact that with

them any peasant or urban commoner could strike down any knight, a direct

threat to the rules of chivalry and the whole social order those rules represented

and served to legitimate.

The pike was a wholly defensive weapon and consisted of a rough-hewn

barricade of sharpened posts scattered about a battlefield. Its aim was to limit the

maneuverability of mounted knights by goring the horses they rode. Without free-

dom of movement and the added force to his lanceblows provided by his horse’s

charge, a mounted knight became a much less lethal fighter.

Armed with these weapons and the willingness to use them, the English were

initially able to tip the scales in their favor. The basic English strategy was to harass

the French as much as possible with small bands of soldiers, led by nobles to be

sure, but relying increasingly on common infantry armed with the new weapons.

The English invaded, plundered, cut down vineyards, burned bridges, and dis-

rupted trade, then fled before the French could amass their feudal armies and rout

them. Surprisingly few pitched battles took place—yet whenever they did, the

English usually won. The first major battle took place in 1346 at Cre´cy, when the

French managed to cut off the English retreat route through Flanders. The English

archers carried the day. According to Jean Froissart (1338–1410), the author of the

greatest contemporary chronicle of the war:

Then the English [longbow] archers stepped forward and shot their arrows

with great might—and so rapidly that it seemed a snow blizzard of arrows.

When these arrows fell on the Genoese [the French ally at the time] and

pierced their armor, they cut the strings of their own weapons, threw them

to the ground, and turned and ran. When the king of the French, who had

arrayed a large company of mounted knights to support the Genoese, saw

them in flight he cried out: “Kill those blackguards! They’re blocking our

advance!” But the English kept on firing, landing their arrows among the

French horsemen. This drove the charging French into the Genoese, until

the scene was so confused that they could never regroup again....[When the

slaughter ended] it became clear that the French dead numbered eighty ban-

THE CRISES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY 385

ners, eleven princes of the realm, twelve hundred knights, and thirty thousand

commoners.

The numbers are bloated, but the general picture is accurate. After Cre´cy the En-

glish forces, led chiefly by the heir to the throne—another Edward, known as the

Black Prince—returned to their harassing strategy for several years. In 1356 an-

other large battle took place at Poitiers with even greater results for the English,

who not only defeated the French but captured their king and carried him back

to London for ransom.

15

Several temporary truces shortly followed, but the final phase of the war

opened in 1415 when the new English king, the hot tempered Henry V, determined

to conquer France outright. A bloody battle at Agincourt in that year, in which

another fifteen hundred French nobles disappeared, opened the door for his con-

quest of the northern third of France. As the English prepared to march south and

take the rest of the country, three fortunate things happened for the French: a

death, a miracle, and a new alliance. First, Henry V contracted dysentery and died

in 1422, depriving England of its most forceful leader since the war began. France’s

weak-minded new king Charles VII (1422–1461) was ill-equipped to seize the op-

portunity this represented, but then the miracle happened. An illiterate seventeen-

year-old peasant girl named Joaneta D’Arc [Joan of Arc, in Anglicized form] in

1428 began to hear heavenly voices telling her to persuade Charles to place her at

the head of the French army and drive the English from the realm. Joan never

professed to understand why God had chosen someone like her to lead an army,

but she obeyed without hesitation. Charles, who may or may not have believed

in her heavenly mission (historians still bicker over it), did assign her a military

command. She cut her hair short, wore men’s clothing and armor, and rode into

battle. Almost in spite of herself she was surprisingly successful and scored some

signal victories. Her courage and modest success helped persuade the French that

they really could win after all—and given the mystical thrust of Joan’s leadership,

to believe that God was on their side.

In 1430 the Burgundians, who were allied with the English against the French,

captured Joan at Compie`gne and sold her to the English, who in turn accused her

of witchcraft—largely a trumped-up charge—and turned her over to the Inquisi-

tion. Here Joan’s descriptions of her mystical voices were closely examined, along

with the explanations behind her supposedly unnatural habit of wearing male

clothing, and she was condemned as heretic. She was burned at the stake in 1431.

16

She had not been on the scene long enough to change the course of the war, but

her effect on improving French morale when it was at its lowest point was

considerable.

What truly brought about the end of the war—the third piece of France’s new

luck—was the Burgundians’ decision to break their alliance with the English and

throw their support behind Charles VII. Burgundian motives are not entirely clear,

15. This led to the French tax revolt known as the Jacquerie. It is worth mentioning that French devotion

to the ideals of chivalry remained so strong that a curious event occurred. The French ambassadors who

forwarded the ransom money to London intentionally shortchanged the English, and bragged of their

cunning to the king, John, after his return to Paris. John was so shocked by this betrayal of chivalric

values that he insisted on returning to captivity in London until the French nobles came up with the

rest of the money. What good was it, he wondered, to fight a war in defense of chivalry if the knights

themselves failed to live up to its code?

16. Noting the irregularities in her trial, the papacy in 1455 reversed the sentence and formally pro-

claimed her innocent of all charges; in 1920 she was canonized as a martyr to the faith.

386 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

but it is possible that Joan’s success in rallying French morale convinced them that

the war would simply continue on and on unless something was done to break

the deadlock. Whatever their reasons, they defected from the English. No longer

forced to fight a two-front war, the French were thus able to drive the English

from their principal northern strongholds of Paris, Rouen, and Guienne. The ex-

hausted English soon sued for peace, and the war finally ended in 1453 with the

English in possession only of the port city of Calais and with the victorious French

united enthusiastically behind their monarch.

Several important consequences of the conflict stand out. First of all, the new

military tactics significantly hastened the demise of feudalism. From the eleventh

century onward, what had justified a permanent, privileged aristocracy who con-

trolled the lives of the peasantry that served it was the fact that the nobles pro-

vided the basic services that upheld social order: They defended the realm with

their own lives; they oversaw the prosperous work of the rural economy, which

was the backbone of economic life; and they provided the essential government

services that maintained order. By the fourteenth century, however, the urban

economy had emerged as the most essential aspect of the medieval world; the

improvement of educational levels among the commoners meant that rulers did

not have to rely on aristocrats for civil services, and the new techniques of warfare

made it clear that henceforth the bulk of military service could be provided by

commoners who needed only enough education to point their crossbows away

from themselves before pulling the trigger. For the cost of maintaining a single

mounted knight, a ruler could instead arm several hundred infantrymen, any one

of whom could, with a good shot, eliminate the knight in a moment.

17

The econ-

omy, civil administration, and military, in other words, had been revolutionized.

Social revolution seemed close behind.

Although hereditary aristocrats retained their influence for centuries to come,

their place in western Europe had changed significantly by the end of the four-

teenth century. As outbreaks like the Ciompi Rebellion, the Jacquerie, and the

English Peasant’s Revolt indicated, masses of rural and urban commoners were

willing to challenge openly the idea of maintaining privilege for a caste that no

longer played its old essential role. Many now railed against not the abuse of

privilege but the very idea of privilege. Why should a mere five to ten percent of

the population continue to have jurisdiction over the masses, control the land,

monopolize the courts, enjoy exemption from taxes, dominate the Church, and be

lauded by poets as the bulwarks of everything civilized in the world, when the

bulk of the essential services in Europe were now provided by people of common

birth? “When Adam delve and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman?” asked

William Langland in his poem Piers Plowman; the meek-sounding question implied

a revolutionary idea—that when God created the world in all its perfection, there

were no “gentlemen,” no aristocrats, no privileged few living off the labor of the

many. There was instead an absolute equality of mankind and therefore the very

notion of ordered hierarchy, perhaps the defining characteristic of the medieval

17. By the end of the Hundred Years War, gunpowder was also widely known (a German monk had

described it as early as the late twelfth century, and Roger Bacon, the radical Franciscan, had determined

its makeup in the thirteenth), but it did not have the same initial impact as the longbow and crossbow

for the simple reason that whereas gunpowder itself was relatively inexpensive to produce, the cannons

and handheld weaponry that employed it were not. Large-scale use of gunpowder by European armies

did not become the norm until well into the sixteenth century.

THE CRISES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY 387

mind, had no place in God’s world. European society had entered a period of

rapid change.

C

HALLENGES TO

C

HURCH

U

NITY

Several important new developments appeared in western religious life at this

time. In the thirteenth century the Church, with the papacy at its head, had per-

vaded medieval society, and the idea of Christendom—the Christian world as a

unified organic whole that shaped and gave meaning to life—held sway as the

dominant ideology, coloring everything from scholastic philosophy to economic

theory, from artistic judgment to political policy. But by the end of that century

there were already clear signs of a major shift in Latin religious life, a change not

in doctrinal content but in spiritual style. The mystical phenomenon—it hardly

seems right to call it a movement—injected a powerful new strain of spiritual

energy among believers everywhere, and the various monastic reforms and new

mendicant orders revitalized religious life. The aged Pope Boniface VIII (1294–

1303) celebrated these achievements (as well as himself) by proclaiming the Jubilee

Year of 1300, a sort of grand ball that the Church threw for itself, with pilgrimages,

special services, the bestowal of indulgences, and festivities throughout Latin

Christendom but focusing especially upon Rome. Popular response exceeded his

wildest dreams, as no fewer than one million pilgrims from all over Europe made

the journey to Rome, singing hymns, chanting, praying, celebrating masses, and

incidentally bringing enormous sums of money into local coffers.

But only five years later a grimmer chapter suddenly opened in the Church’s

history. As we have seen, many Catholic faithful, both high-and low-born, had

become dissatisfied with the Church’s growing worldliness, its concern with cru-

sades and taxation, its attempt to manipulate the international economy, its head-

long push into politics, and its meddling with the intellectual activities of the

universities. This anticlericalism had many roots and took many forms, but it

frequently, if not usually, bore some relation to the centralization of ecclesiastical

authority, which many began to believe had progressed beyond tradition and rea-

son. Innocent III, around 1200, had envisioned a papal monarchy in which the

Church would be involved in secular affairs as an impartial arbiter; Boniface VIII,

around 1300, rejected the notion of disinterestedness and insisted on the Church’s

right to control whatever it wished to control. His pontificate marked a turning

point in the history of the papacy. Much of whatever popular support for the

Church was generated by his Jubilee was undone by his promulgation of two

bulls: Clericis laicos (1296) and Unam Sanctam (1302). At first glance the texts appear

relatively harmless, but their implications were considerable.

Clericis laicos dealt with taxation. Philip IV of France (1285–1314), known as

the Fair but, like Innocent, a rather bullheaded man, was chronically short of

money to pay for his ambitious political schemes and decided to raise his income

by heavily taxing the French clergy. Boniface responded immediately with his bull,

which imposed a penalty of excommunication on anyone taxing clerical property

without the Supreme Pontiff’s direct authorization. The bull irritated Philip, of

course, but it also angered many commoners in France and elsewhere because

they regarded it as further evidence of the Church’s quick action whenever it came

to assuring its own well-being, whereas it was frustratingly slow in responding

to the needs of the masses. But the bull touched a raw nerve with the churches,

too, since state taxation of local churches was hardly new—but by tradition such

388 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

taxation had been done with the voluntary consent of the clergy themselves. The

pope seemed to be undermining the authority of the local clergy in order to max-

imize his own. Boniface and Philip reached a temporary compromise, but in 1301

Philip renewed the fight in an underhanded way by circulating a forged document

that purported to be a new bull from Boniface, one in which the pope supposedly

claimed direct temporal authority over the French king. Philip’s timing was right.

Popular outrage over Boniface’s supposed claims broke out all over France.

Boniface responded by condemning the phony bull and issuing a genuine new

one, Unam Sanctam, which made even more extravagant claims for papal power

than did the French fake. Unam Sanctam was a short, bellicose, and utterly una-

pologetic declaration of papal supremacy over everyone, everywhere, and at all

times. It offered little by way of argument or justification of its claims. It reads

like a communique´ from a commander-in-chief—which of course is precisely what

Boniface intended.

We are compelled by our faith to believe and maintain—and we do firmly

believe and candidly confess—that there is only one holy, catholic, and ap-

ostolic Church, outside of which neither salvation nor forgiveness of sins is

possible...This one and only Church can have only a single body and a

single head—namely Christ and His vicar St. Peter (and Peter’s successor); it

is not a two-headed monster....We are told in the Holy Gospel that in

Christ’s fold are two swords, one spiritual and one temporal....But both

swords, the spiritual and the material, are under the control of the Church.

. . . The spiritual authority judges all things but is itself judged by no one....

In fact we hereby declare, proclaim, assert, and pronounce that it is absolutely

necessary to every single human being’s salvation that he be subject to the

Roman pontiff.

It was the tone that angered people more than anything else; after all, nearly every

assertion in the bull had been made by earlier popes (most of whom had had the

diplomatic sense to couch their claims in less offensive language). Boniface’s pon-

tificate ended in misery, as popular opinion swelled against him across the Con-

tinent. Philip tried to capitalize on the old man’s unpopularity by dispatching a

force of three hundred cavalry and a thousand infantry armed with a warrant for

the pope’s arrest—charging him, outrageously, with offenses that ranged from

murder and black magic to every imaginable variety of sexual misconduct. Philip’s

men found Boniface at his residence in Anagni, south of Rome; they stormed the

palace, broke down doors and windows, stole everything they could find that was

of value, set fire to the building, and finally seized the pope in his private chamber.

Their rough treatment proved to be too much for the eighty-five-year-old man,

who died soon thereafter of traumatic shock while still in the soldiers’ custody.

Two years later, after the brief pontificate of Benedict XI, Clement V became

pope (1305–1314). Although duly elected by the College of Cardinals, he was not

popular with the people of Rome, who took to the streets to protest. Clement was

a Frenchman, and the rumor ran through Rome that his election had been engi-

neered by the French king. The protests turned violent, forcing Clement and the

majority of cardinals who had voted for him to run for their lives. They escaped

to southern France, where they were granted residence at Avignon by Philip IV.

Thus began the period known as the Avignon Papacy (1305–1378). The popes of

this period—there were eight of them, all French—were viewed with suspicion

and disdain by contemporaries, and their reputations have hardly improved over

the centuries. Most of them were well intentioned, pious, and capable figures, but

THE CRISES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY 389

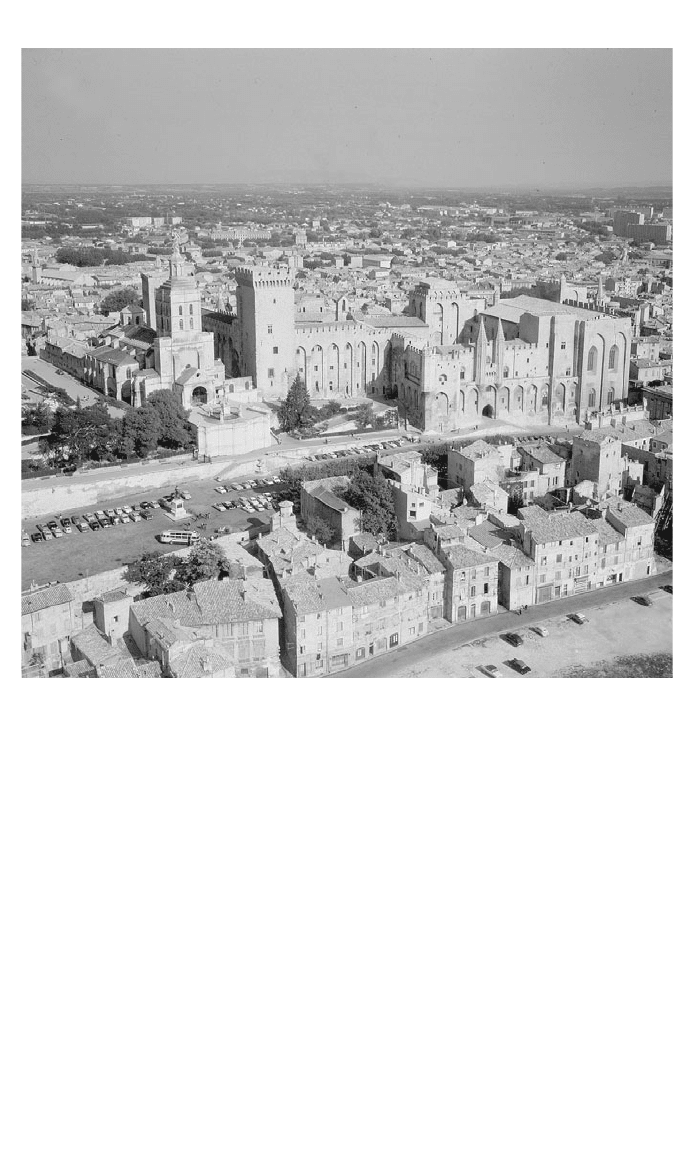

Papal palace at Avignon. Fourteenth century. The palace constructed for the papal

court during its exile in Avignon (1305–1378) looks vaguely, when seen from the

air, like a maximum-security prison — which in a sense it was. From ground level it

is a massive, imposing stone pile. The popes brought their entire administrative

machiner y with them to southern France, and few of them ever set foot outside

their fortified bunker. (Giraudon/Art Resource, NY)

they were never able to shake off the imputation that they were in effect servants

to the French king, doing his bidding in return for his protection. Moreover, the

fact that the popes in Avignon built themselves a massive, foreboding, and down-

right gloomy palace behind thick stone walls and with omnipresent armed guards

made it seem that they had in essence turned their backs on suffering Christen-

dom. The popes seldom ventured into public and were generally seen only by

courtiers and ambassadors, who offered bribes to the guards and paid graft to

palace officials in order to have their cases heard by the pontiffs. Financial cor-

ruption ran rampant, until it seemed that the concern with money, and the power

that money makes possible, was the popes’ only concern.

Most of the Avignon pontiffs don’t fully deserve their bad reputations; they

simply had the misfortune to stand at the head of the Church at the very time

that the medieval world entered its most calamitous century. The Great Famine,

390 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

the Black Death, the Hundred Years War, the dissolution of the German Empire,

the stalling out of the crusade movement, the collapse of the medieval economy,

the resurgence of heresy, the decline of Byzantium, and the rise of a newly ag-

gressive Ottoman Turkish state formed a knot of enormous problems that even a

healthy and popular papacy would have found difficult to deal with. But the popes

did add to their own troubles in many ways. Their obsession with money—which

in a few instances even reached the point of excommunicating poor communities

whose taxes were past due—struck Latin Christians as cold and brutish behavior.

Respect for the papacy began to fall, and popular anticlericalism rose accordingly.

The humanist poet Petrarca described the Avignon Papacy as a new “Babylonian

Captivity” of the Church—a reference to the Jewish servitude under the ancient

Persian Empire—and openly lamented the corruption and worldliness at the cu-

ria’s center. Even more openly, St. Catherine of Siena (1347–1380) fearlessly criti-

cized the papal court and its obsessions with money, wars, and political maneu-

vering. Her surviving letters to popes and princes, scholars and commoners, of

which there are more than four hundred, are filled with plain spoken outrage at

the Holy See’s miserable condition.

Several attempts were made to return the popes to Rome; after all, is the pope

truly the leader of the Church if he is not the acting bishop of Rome? Local con-

ditions made that difficult, however, and the (sole) Avignon Papacy finally ended

only through creation of yet another crisis. In 1377 Pope Gregory XI bravely ven-

tured back to Rome but died early the next year. The Roman crowds took to the

streets demanding that an Italian pope be elected, to wrest the Holy See from the

control of the French. The cardinals, fearing for their lives, accommodated them

by electing an Italian, Urban VI (1378–1389); however, most of the cardinals then

immediately raced back to Avignon and declared Urban’s election null and void

(since it had occurred only under the threat of mob violence) and elected another

Frenchman who took the name Clement VII (1378–1394). Thus began what is

known as the Great Schism. From 1378 until 1417, when the dispute was finally

resolved, there were two papacies—one in Rome and another in Avignon. Each

had its own College of Cardinals, its own corps of court officials, its own money-

making apparatus. And each, of course, ordained and consecrated its own order

of bishops. Two separate churches were in the making, each regularly anathema-

tizing the other and courting support from secular rulers by offering blessings,

indulgences, praise, and a share of ecclesiastical revenues. As the first two rival-

popes died, each church selected a sucessor, continuing the split into a second and

third generation. The stakes were high, and the popes and their underlings looked

for support wherever they could find it among Europe’s elites. They were not

particularly selective in deciding which politicos to back and be backed by. One

of the Avignon-based popes, Benedict XIII (1394–1423), enthusiastically supported

as a champion of Christian order the drunken, boorish German emperor Wenceslas

(1378–1400)—a man who once, angered by a burnt dinner, ordered his cook to be

roasted on a spit.

Resolving the Schism was difficult, for each side of the dispute could legiti-

mately claim to have been canonically selected by the (or a) College of Cardinals.

Even more fundamental was the question: Who has authority to judge the pope

or popes? No one wanted to turn to the German emperor and risk reopening the

Church-State conflicts of the twelfth century, and the kings of England and France

were too immersed in the Hundred Years War to give much attention to the papal

rift; in fact they were benefiting from the split too much to want to rush to heal

it. The jurisdictional problem was critical, since its resolution would establish a

THE CRISES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY 391

precedent for all future disputes within the Church. By the first years of the fif-

teenth century, many theologians began to advocate a universal church council as

the only way out of the mess. Councils, after all, had been a common tradition

within the Church for addressing all sorts of internal problems. But never before

had a council been convened in order to pass judgment on the papacy itself. If

such a council met, wouldn’t its actions suggest that the Holy See was subordinate

to it? If so, in what sense is the pope the head of the Church? Who had the

authority to summon a council? Who would host it? The call for a council raised

a host of constitutional questions—but the fact that a council was ultimately agreed

to is an indication of how grave a problem the Schism had become. Over five

hundred prelates representing both sides of the split met at the Council of Pisa in

1409. With great pomp the Council denounced both popes as “notorious schis-

matics and heretics guilty of perjury and bringing open scandal to the entire

Church” and deposed them. In their place the Council elected a new pope, Al-

exander V (1408–1409). But the first two popes, Gregory XII and Benedict XIII,

stubbornly refused to recognize the Council’s actions, leaving the Church in the

humiliating position of having three popes. Popular frustration reached record

levels, and political opportunists like the Neapolitan king began to move their

armies into the Papal State itself. There seemed no other option, so a second coun-

cil was convened at Constance in 1417. The Council of Constance deposed all three

popes and elected Martin V (1417–1431), effectively putting an end to the Schism.

18

But the Council of Constance also asserted in the strongest possible language the

supremacy within the Church of an ecclesiastical council. The Council’s decree

Haec Sancta declared that a council “holds its power directly from Christ, and that

all people, of whatever rank or dignity, even the pope himself, are required to

obey it in all matters relating to faith, the end of the Schism, and the general reform

of God’s Church....[Moreover] any person of whatever position, rank or title,

even a pope, who stubbornly refuses to obey [a council]...shall be subject to its

severe and just punishment.” This was a far cry from Boniface VIII’s Unam Sanc-

tam. The so-called conciliar theory remained a lively debate within the Church for

well over a hundred years and ultimately helped trigger the Protestant Reforma-

tion—since one of the specific points on which Martin Luther was officially con-

demned in 1521 was his assertion that a council has authority over the pope.

The Great Schism added powerfully to the disappointment and disgust felt

by many Christians for the upper echelons of the Church. Piety continued to run

strong and probably even increased in the face of so many troubles throughout

the century, but many faithful began to turn away from regular church practice

and to seek new expressions of their devotion. Lay confraternities began to flour-

ish, groups in which the Scriptures were studied, hymns sung, and prayers led by

educated laymen and laywomen. All-female houses of beguines remained popular

too, following ideals of simplicity and service. Within the Church structure, signs

of discontent were rampant. The Franciscan order split angrily over the notion of

ecclesiastical wealth, with the most radical friars (the Franciscan Spirituals) de-

manding an ideal of “apostolic poverty.” Christ and the original twelve apostles,

they maintained, had owned no property; thus they concluded not only that re-

linquishing wealth was a virtuous act but that possessing wealth was in fact a

vice. The Spirituals called upon the Church at all levels to abandon all property

18 Two of the other three popes reluctantly accepted their deposings for the good of Christendom. But

Benedict XIII angrily held out until his death in 1423, hurling excommunications and anathemas at

everyone from his castle in Spain.

392 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

and wealth, and insisted that a refusal to do so would imply the negation of the

Church’s spiritual authority. This notion predictably horrified the Holy See; Pope

John XXII (1316–1334) condemned the renegade order, but its members had gained

considerable popularity among the common people.

Discontent led many of those people into heresy. Two of the most significant

heretical groups of the fourteenth century were the Lollards (or Wycliffites, after

their founder John Wycliff) in England and the Hussites, followers of the religious

and social reformer Jan Hus, in Bohemia. John Wycliff (1330–1384) was the Master

of Balliol College at Oxford University and a popular preacher. He was a prolific

writer and original thinker, but he might never have caused a stir had he not been

pulled into politics by King Edward III in 1374. Edward appointed Wycliff to serve

on a commission to negotiate with papal representatives regarding the relationship

between the English Church and the perogatives of the monarchy. Like other mon-

archs of the time, Edward hoped to capitalize on the Avignon Papacy’s unpopu-

larity by winning an extention of his control over ecclesiastical appointments and

ecclesiastical revenues. Wycliff came away from the experience disillusioned with

both the clerical and secular powers, and he began to entertain a number of beliefs

that put him at odds with both. He argued that the exercise of authority on earth,

whether it be ecclesiastical or political, is a gift from God and is not an intrinsic

right of those individuals and institutions that wield it; such authority is external

to those individuals, not a constituent element of them. From this it follows—and

this is where Wycliff got into trouble—that the moral right to exercise authority

depends on the moral worthiness of the person in power. A secular or clerical

authority whose personal behavior is at odds with God’s just expectations effec-

tively nullifies his own legitimacy as an earthly power. By this logic, a secular

ruler may justifiably usurp the authority and confiscate the property of unworthy

clergy (an idea that no doubt made Edward III smile); but so too might a righteous

populace justifiably usurp the authority and confiscate the property of an unwor-

thy king (at which point the smile presumably left Edward’s face).

Wycliff had a predilection for provocative ideas and he enjoyed the shock

value of what he said and wrote. But it is by no means clear that he endorsed

political or ecclesiastical revolution, even though many of his readers believed him

to have done so. His arguments linking moral worthiness and earthly dominion

can be read as nothing more radical than a call for those with power in the world

to improve their moral lives. Nevertheless, his followers, who became known as

Lollards (from a medieval Dutch word lollaerd, meaning a “grumbler”), seized upon

his ideas and soon surpassed them. The Lollards, who came chiefly from the ar-

tisanal classes and played an important role in fomenting the Peasants’ Revolt of

1381, opposed the subordination of the English Church to Rome, the temporal

authority of the clergy, the doctrine of transubstantiation,

19

the demand for clerical

celibacy, and the veneration of religious images. The Lollards also demanded that,

in order to remain valid ministers of God’s word, all clergy had to attend regularly

to their parishes’ needs (a notion that Wycliff, an absentee-rector of several rural

parishes, might have balked at), and they insisted most especially on the need to

have English translations of the Bible available to all believers.

The Catholic Church had always been opposed to vernacular translations of

the Scriptures and had squelched earlier efforts in this area with a heavy hand but

not out of a desire to keep God’s message from the people. There were three main

19. The Catholic doctrine that in the Eucharist the material essence of bread and wine is fundamentally

and absolutely changed into the body and blood of Christ.

THE CRISES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY 393

reasons for prohibiting translations of Scripture: first of all, the belief that St. Je-

rome’s Latin Vulgate was itself a divinely inspired rendition, and therefore not to

be tampered with; second, the conviction that one of the chief strengths of Chris-

tianity was its transcultural nature, and that as long as all Christians read the

Scriptures in the same language and spoke to each other in the same tongue, that

transcultural element would not be lost; and third, the belief that it mattered a

great deal, even if only as a matter of individual spiritual discipline, for the faithful

to come to the Church’s language, not vice versa. But Wycliff produced a complete

English version of the Bible—hardly a model of accuracy and not even the first

such version—that circulated widely, if surreptitiously, throughout England. His

ideas had considerable appeal.

And not only to the English. King Richard II (1377–1399) married a Czech

princess named Anne, and this union resulted in heightened contact between their

two realms; Wycliff’s ideas soon circulated throughout the Czech territories—

known as Bohemia in the Middle Ages—and he became briefly one of the most

popular authors in the land. Among his most avid readers was the Czech nation-

alist and earnest reformer Jan Hus (1372–1415). Hus was a professor of theology

at the University of Prague (the first university established in eastern Europe) and

served as confessor to the Bohemian queen. He shrank from some of Wycliff’s

most radical views but generally endorsed the main thrust of his ideas. Even so,

Hus might never have been a public figure were it not for his entanglement in

politics. Bohemia was technically part of the Holy Roman Empire and was as

independent-minded as most of the provinces. Two matters thrust Hus into the

political spotlight in 1409. First, the emperor Wenceslas (the one who got very

angry when his dinner was overcooked) ordered a reorganization of the University

of Prague in which a majority of the leading positions went to ethnic Czechs. The

disgruntled German faculty stormed away and founded a rival new university at

Leipzig where they spread rumors that Prague was in the grip of heretical Wy-

cliffites led by Hus. Second, several of the Leipzig faculty ventured to the Council

of Pisa, which was then involved in the embarrassing business of turning a Church

torn between two popes into a Church torn between three. The king back in Prague

supported one of the popes, the Archbishop of Prague supported a second (to

whom he owed his archbishopric), and Hus was inclined toward the third. Disgust

over the situation started to drive Hus into a closer adherence to Wycliff’s heretical

views.

Hus finally was summoned to answer charges of heresy at the Council of

Constance. His trial was hardly a fair one, since he was allowed only to give one-

word answers to the questions put to him; he wrote many letters to friends and

supporters back in Prague in which he bemoaned not being allowed to explain

his ideas on transubstantiation, the role of the clergy in the state, and the doctrine

that moral uprightness necessarily affects clerical legitimacy. In the end he was

condemned on thirty of forty-five specific charges and was burned at the stake.

Although he died in the conviction that he was a good Catholic, Hus’ execution

was later regarded as the martyrdom of a proto-Protestant.

The problems confronting the Church in the fourteenth century proved too

much for it. Even though many of those problems were not of its own making,

the Church had to adapt to appallingly difficult conditions. It might have made

some better choices at particular moments, but the Church’s great misfortune was

that Latin Europe went into a tailspin precisely at the point of a fundamental

constitutional crisis within the Church—and that until the crisis was resolved, no

proper campaign to address the troubles of the age could be forthcoming. The