Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

414 TWO EPILOGUES

have more trades than are proper. One person is a vintner, yet he also sells

salt and cloth. Another is a tailor, yet he engages in commerce. Everyone who

is able to do so buys and sells anything at all, whatever they think will bring

them a profit. But listen again to what our imperial law commands (our an-

cestors, bear in mind, were not fools): individual trades were created precisely

in order that everyone should thus have a chance to earn his daily bread

without trespassing upon another’s trade; in this way the needs of the world

are met and every man can support himself....

All matters of citizenship and observance of law ought to be maintained

by imperial authority, but the aristocrats, who still control most of the land,

live almost as emperors in the own right upon their lands. These counts,

barons, knights, and nobles...continue to reduce free farmers to dependence

and bind them as serfs....Itisscarcely to be believed that such an injustice

still exists in the Christian world....

The fifteenth-century English writer Thomas Malory devoted his years in various

prisons (for crimes ranging from extortion, assault, and theft, to rape) to narrating

in vivid style the tales of King Arthur and his idyllic court: a farewell to an ide-

alized past in the face of ugly modern novelties.

1

But despite all the lamentations for the supposedly fast-vanishing medieval

norms and manners, many of those traditions refused to go easily. In the realm of

politics, a series of German rulers strove for decades to restore the imperial office

to what it had been in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; the feudal barons,

though largely outmaneuvered in terms of political office and economic might,

retained enormous influence in society and could still, when situations warranted

it, bring governments to a halt. The Church, challenged and even derided on so

many fronts, nonetheless offered the closest thing the west had to an umbrella-

institution and a unifying ideology. Strict Catholic orthodoxy may have been on

the wane, but not Christian zeal; the religious energy that had so long character-

ized medieval society still reigned supreme but now flowed through a plethora of

channels.

Tough economic conditions prevailed from mid-fourteenth to mid-fifteenth

century. The population of England, for example, fell nearly forty percent; more-

over, this decline was matched by the decline in wool production and was sur-

passed by the decrease in wine production. Such decreases were felt throughout

the Continent, and the weakened commercial and industrial base made it difficult

for governments to find revenue. An impressionistic inventory of governmental

incomes made by a Venetian writer compared governmental incomes in 1423 to

what they had been only a century earlier. (See Table 19.1.) The specific figures

are not to be trusted, but the general trend they illustrate is correct. Given these

sorts of economic realities and the pained sentiments that surrounded them, it is

not surprising to find that much of western Europe entered a period of retrench-

ment as the medieval world gave way to the early modern one. But retrenchment

means more than a change in scale; it also involves an altering of priorities and a

1. Like many others, Malory dreamed of a time when Arthur would return and restore justice and

order to the world. Here is his ending to the tale of Arthur’s death: “Yet some men say in many parts

of England that King Arthur is not dead, but had [been led] by the will of Our Lord Jesu into another

place. And men say that he shall come again and he shall win the Holy Cross. Yet I will not say that it

shall be so, but rather will I say, Here in this world he changed his life. And many men say that there

is written upon his tomb this verse: ‘Hic iacet Arthurus, rex quondam rexque futurus’ [Here lies Arthur, the

once and future king].”

CLOSINGS IN, CLOSINGS OUT 415

Table 19.1 Comparison of State Revenues

Realm

State Revenues in 1420

(in Venetian ducats)

State Revenues in 1320

(in Venetian ducats)

Bologna 400,000 200,000

Brittany 200,000 140,000

Burgundy 3,000,000 900,000

England 2,000,000 700,000

Florence 400,000 200,000

France 2,000,000 1,000,000

Milan 1,000,000 500,000

Portugal 200,000 140,000

Spain 3,000,000 800,000

Venice 1,100,000 800,000

hardening of resolve. We see all these characteristics at play in the developments

of the late medieval world.

T

HE

L

AST

Y

EARS OF

B

YZANTIUM

The restoration of the Byzantine Empire in 1261 brought to power the last Greek

dynasty, the Paleologoi. But power is hardly the right word to use since the restored

rulers began with little and steadily lost whatever they had begun with; between

1400 and 1453, when the Ottoman Turks finally wiped out the last traces of the

empire, the Byzantine state was little more than the city of Constantinople, an

isolated municipality surrounded by hostile forces. The last two centuries of Byz-

antine history are essentially the history of a congeries of independent principal-

ities—some Greek-led, others still Frankish-controlled—that paid a grudging lip

service and occasional taxes to the Paleologoi in Constantinople. Even the Greek

Orthodox Church, traditionally the principal bulwark of imperial power, paid little

attention to the emperors. This inattention turned into open resistance when,

throughout the fourteenth century and well beyond 1400, emperor after emperor

desperately sought help from the west by again offering to subordinate the Or-

thodox Church to the papacy—the very stratagem that had initiated the crusades.

The empire’s main weaknesses were economic and military. Control of the

sea-lanes having long since passed into the hands of the Italians, the Saljuq Turks,

and the Mameluks, the Byzantines suffered from commercial dependency. Forced

to rely on others for the import and export of goods, they faced constant demands

for more commercial privileges, more trading monopolies, more tax exemptions,

from the foreign merchants who were in a position to set their own terms. The

drain this dependence represented on imperial revenues made it impossible for

the rulers in Constantinople to finance any sort of recovery, whether military or

otherwise. Land revenues also declined because the local lords could simply re-

fuse, with impunity, to send the rents and taxes they owed to the court. Late

Byzantine economic policy took the form, symbolically, of selling off the family

silver by granting out revenues, privileges, and exemptions left and right. At a

certain point, the symbolic became real: One late emperor, John V, even found it

necessary to pawn the imperial crown jewels to the city of Venice.

416 TWO EPILOGUES

The military threat came in several waves. The Fourth Crusade and the period

of the Latin Empire (1204–1261) had wreaked devastating violence on the coun-

tryside. As the westerners gobbled up whatever they could of Greek land and

wealth, the Saljuq Turks and Egyptian Mameluks carved up the Holy Land and

Anatolia between them, while most of the Balkans were taken over by the Bulgars

and Serbs. The onslaught of the Mongols in the thirteenth century had shaken

matters up even more by destroying the ’Abbasid caliphate, threatening the Bul-

gars (who in turn pressed further southward into Byzantium), and weakening the

Saljuq Turks in Anatolia. The decline in Saljuq power enabled a rival group, the

Ottoman (or Osmanli) Turks, to rise against them. The Ottomans had settled in

northwestern Anatolia in the thirteenth century, under their leader Osman, as a

semi-independent client nation under Saljuq control, but they quickly emerged as

an autonomous power when Saljuq authority disintegrated. Keeping their main

power base in western Anatolia, the Ottomans created a tightly organized army

that in 1354 crossed the Bosporus and entered southeastern Europe to establish

the first Islamic beachhead in Christendom since the conquest of Spain in 711. The

Bulgars and Serbs, though no friends of the Byzantine state, rushed to the defense

of the Orthodox faith. They were defeated in a quick series of clashes, though, the

largest being the Turkish victory over the Serbs at the battle of Kosovo in 1389.

The Ottomans then established a Balkan capital at Adrianople [modern Edirne]

and proceeded thence to advance on Constantinople itself.

As Byzantium’s demise grew imminent, western Europe’s contacts with east-

ern Europe increased. It was clear, after all, that the empire had long served as a

buffer zone between the Christian world and the Islamic, between the European

and the Asian, and in its impending absence the states of eastern Europe would

become the buffer. Apart from Saxony and the East March territories of the

German empire, Latin Christendom had had little to do with eastern Europe ec-

onomically or culturally, but, starting in the fourteenth century and continuing

into the sixteenth, the importance of relations with the east grew dramatically.

Therefore, when Constantinople first appeared in serious danger of falling to the

Turks, the west responded, predictably, with yet another crusade. What was sur-

prising, though, was the degree to which the westerners put aside their own

squabbles in order to bring the crusade to pass. The English and French tempo-

rarily halted their Hundred Years War conflicts, the Burgundians joined in as well,

and even the two rival popes (one in Rome, the other in Avignon, as a result of

the Schism) set aside their differences. An army of about fifteen thousand soldiers,

made up roughly equally of French, Germans, and Burgundians agreed to serve

under the command of King Sigismund of Hungary, gathered near Budapest in

the summer of 1396 and began to march southeast against the Ottoman stronghold

of Nicopolis,

2

where they were joined by Venetian and Genoese auxiliaries. It took

some time for the sultan, Bayezid, to march up from Constantinople, but when he

arrived in September of that year he commanded a far superior force. What de-

cided the battle, however, was another outbreak of chivalry among the French

knights. They insisted on being placed in the front line so that they could lead the

charge uphill against an enemy whose tactics they knew nothing about. As had

happened to them as Cre´cy and Poitiers at the hands of the English, they were

cut down by volleys of Turkish arrows and their horses were impaled by networks

of spiked barricades. In the confusion that followed, Bayezid easily wiped out the

2. Modern Nikopol, on the lower Danube in Bulgaria.

CLOSINGS IN, CLOSINGS OUT 417

rest of the crusaders. A second crusade effort in 1440 ended in another crushing

European defeat at Varna, on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast.

This left most of southeastern Europe open for the Turks to take, with the

grand culmination of seizing Constantinople now apparently inevitable. Ottoman

goals were temporarily interrupted by the appearance of a rival in eastern Ana-

tolia, where a warlord named Timur the Lame (known in the west as Tamerlane)

had gathered together a mostly Mongol army in a last attempt to challenge Ot-

toman power. Timur eventually gave up on Asia Minor and focused on securing

control over central Asia and Persia, a tactic that freed the Ottomans to close in

on Constantinople. The imperial city fell to the sultan Mehmet II “the Conqueror”

on 29 May 1453.

3

Repeated calls for western aid to recover the city failed.

4

From the twelfth century onward, a renewal of interest in Greek learning and

art had been growing in the west. The conquest of Constantinople in 1204 accel-

erated that interest by making available a tremendous number of plundered man-

uscripts and artifacts, but the final fall of the empire to the Ottomans in 1453 had

little direct effect on the revival of Hellenism in the west since nearly everything

that was ever going to be transmitted westward had already been done so by then.

What is observable, however, is a modest but significant migration of Greek-

speaking peasants and urban workers westward. The peasants generally settled

as tenant farmers in their new lands or sometimes ended up on the slave market

(western qualms against the holding of Christians as slaves did not extend to

Orthodox Christians); the latter figures, most of whom settled with their owners

in Italy and Sicily, often found work as domestic servants and tutors, and helped

to teach Greek to new generations of westerners hungry for Hellenism.

T

HE

S

EARCH FOR A

N

EW

R

OUTE

TO THE

E

AST

The Ottoman advance, the Byzantine collapse, and the political upheaval of central

Asia in the wake of the Mongols cut Europe off from southern and eastern Asia,

with which it had had important and highly profitable commercial ties since the

twelfth century. This development, coming as it did when the bottom had fallen

out of the European macroeconomy, provided impetus to a long-held desire to

secure direct relations with the east. The widely reported, if somewhat distrusted,

reports of figures like Marco Polo of the willingness of the people in China to

trade with the Europeans and of the immensity of the wealth to be gained by such

3. The siege succeeded thanks in large part to some immense cannons Mehmet had had built for him

by Hungarian engineers: The largest of these was reported to shoot cannonballs weighing twelve hun-

dred pounds apiece. Even Constantinople’s thick walls could not withstand a barrage like that.

4. Consider this excerpt from a speech by Pope Pius II in 1459: “We watched [the Turks’] power increase

day by day, as their armies overran Hungary after they had already subdued Greece and the Balkans—

so that now the faithful Hungarians suffer innumerable outrages. We feared that once the Hungarians

fell the Germans, Italians, and rest of the Europeans would be next; this may still happen if we do not

take care, and this would be a catastrophe that would surely result in the destruction in the Christian

faith.

“We decided to take action to avoid this fate by summoning a Church Council where all the princes

and people might come together in defense of Christendom....Butweareashamed to find the People

of Christ so indifferent. Some prefer to indulge in luxury and pleasure, while others simply dedicate

themselves to their earthly greed.

“The Turks never hesitate to give up their lives for their vile faith—yet we cannot put up with the

smallest expense or endure the smallest hardship for the sake of Christ and his gospel. I say to you

truly, if Christians continue to live in this debased manner then we are all finished.”

418 TWO EPILOGUES

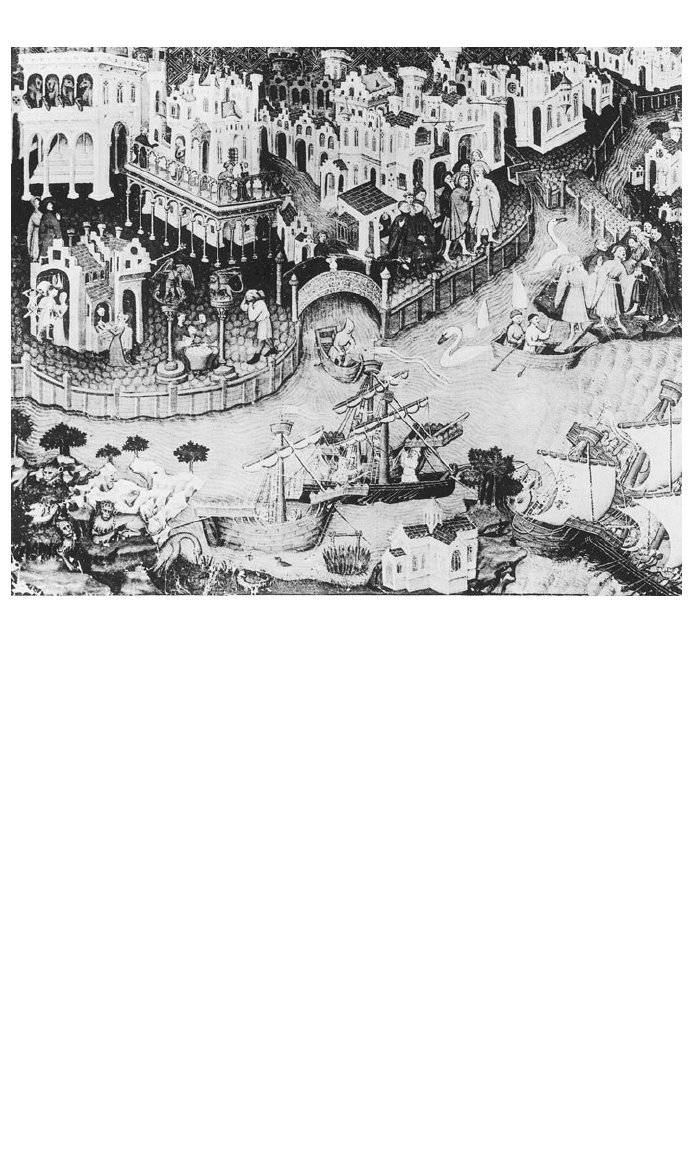

Detail from a copy of Marco Polo’s Travels. Marco Polo (1254–1324) was a Venetian

merchant who ventured east along the caravan routes and spent twenty-four years in

the east, principally in China, as a trade-inspector for the great Mongol leader Kublai

Khan. In 1295 he returned to Venice and served in her naval forces against the

Genoese. Imprisoned for three years in Genoa, he dictated the memoir of his eastern

adventures to a fellow prisoner. This book, known as the Travels or the Book of

Marvels, was widely read. In this manuscript illumination Marco is shown, in the

large ship at the bottom-center, departing from Venice (recognizable by the canals and

the Piazza San Marco) on his way east in 1271. (Foto Marburg/Art Resource, NY)

contact made the idea irresistible. Many missionaries and merchant-adventurers

made their way east in the years after Marco Polo’s memoir-travelogue appeared,

and they corroborated all his claims. The Franciscans, in fact, had established

several churches in Beijing by the middle of the fourteenth century, and by 1400

eastern and southern China were dotted with dozens of Franciscan and Dominican

houses. Possibilities for trade seemed promising, considering the welcome given

to these first arrivals. But the Mongol and Ottoman domination of the eastern

Mediterranean and central Asia meant that no hope existed for maintaining the

traditional trade routes over land. A new way had to be found.

The chief problem was technological: How were the Europeans to reach the

east? Europe’s maritime tradition had developed in the context of easily navigable

seas—the Mediterranean and the Baltic (and, to a lesser extent, the North Sea)—

not of vast oceans. New types of ships were needed, new methods of finding one’s

CLOSINGS IN, CLOSINGS OUT 419

way, new techniques for financing so vast a scheme. The sheer scale of the in-

vestment it took to begin commercial expansion at sea reflects the enormity of the

profits that such east-west trade could create. Spices were the most sought-after

commodity. Cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and pepper were so highly valued that

European merchants would accept quantities of them as money if a fellow mer-

chant was momentarily cashless. Spices not only dramatically improved the taste

of the European diet (or, in the case of spoiled meat, could be used to hide the

taste) but they were also used to manufacture perfumes and certain medicines.

But even high-priced commodities like these had to be transported in large bulk

in order to justify the expense and trouble of sailing around the African continent

all the way to India and China.

The principal seagoing ship used throughout the Middle Ages was the galley,

a long, low ship fitted with sails but driven primarily by oars. The largest galleys

had as many as fifty oarsmen. Since they had relatively shallow hulls, they were

unstable when driven by sail or when on rough water; hence they were unsuitable

for the voyage to the east—even if they hugged the African coastline, they had

little chance of surviving a crossing of the Indian Ocean. Shortly after 1400, ship-

builders in Majorca, Spain, and Portugal began to develop a new type of vessel

properly designed to operate in rough, open water: the caravel. It had a wider and

deeper hull than the galley and hence could carry more cargo; increased stability

made it possible to add multiple masts and sails. In the largest caravels, two main

masts held large square sails that provided the bulk of the impetus driving the

ship forward, while a smaller forward mast held a triangular-shaped lateen sail

which could be moved into a variety of positions to manuever the ship. It appears

that the new design owed something to the Muslims it hoped to eliminate from

the Asia trade; lateen sails had been used by Muslim fleets operating in the Indian

Ocean for roughly a hundred years.

The astrolabe had long been the primary instrument for navigation, having

been introduced in the eleventh century. It operated by measuring the height of

the sun and the fixed stars; by calculating the angles created by those points, it

determined the degree of latitude at which one stood. (The problem of determining

longitude, though, was not solved until the eighteenth century.) By the early thir-

teenth century, western Europeans had also developed and put into wide use the

magnetic compass, which helped when clouds obliterated both the sun and stars.

The Majorcans of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were the premier map-

makers of the age, and their maps, refined by precise calculations and the reports

of sailors, made it possible to trace one’s path with reasonable accuracy. Certain

institutional and practical norms had become established as well. A maritime code

known as The Consolate of the Sea, which originated in the Catalan regions of the

Crown of Aragon in the fourteenth century, won acceptance by a majority of sea-

goers as a normative code for maritime conduct; it defined such matters as the

authority of a ship’s officers, protocols of command, pay structures, the rights of

seamen, and the rules of engagement when ships met one another on the sea lanes.

Thus by about 1400 the key elements were in place to enable Europe to begin its

seaward adventure.

But another problem remained: What could the westerners trade for the spices

and silks of the east? The Chinese had little use for the heavy wool cloth produced

in Europe, and they wove finer cottons and silks that the west could produce.

Foodstuffs did not travel well over such distances and through such harsh cli-

mates, even if the west could produce them in sufficient quantities. These consid-

erations left only metalwares (generally too heavy and bulky to be profitable) and

420 TWO EPILOGUES

gold or silver. Consequently the European traders who worked their way slowly

along the African coastline after 1400 traveled with hoards of gold and silver

aboard, along with the bulk commodities that they traded in Africa in return for

yet more gold and silver. The effort to reach China represented a substantial drain

on European supplies of precious metals, with concomitant implications for its

currencies. It was not until the accidental discovery of the New World that the

depleted reserves of precious metals were replenished.

The expansionist adventure had enormous consequences. Obviously, in the

ultimate discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492, an entire

new chapter in global history was begun. But even before that epochal date, an

important change had occurred. Throughout the medieval centuries, the geograph-

ical, economic, and cultural heart of European life had been the Mediterranean

Sea. But with the start of the maritime expansion, the advantage had clearly begun

to pass to the Atlantic seaboard states. It is hardly a coincidence that Europe’s first

explorers sailed out of Spain and Portugal, quickly to be followed by the French,

the Dutch, and the English. They all enjoyed direct access to the sea, while the

Mediterranean states remained in their own matrix of commercial and cultural ties

that were, for the time being, made sluggish by the changes in the geopolitics of

the region. The movement of the center of the European macroeconomy from the

Mediterranean basin to the Atlantic seaboard was an enormous structural shift

that changed the economic and political ordering of Europe. That shift would not

occur in full force until well into the fifteenth century, or even into the six-

teenth, but the process had clearly begun around 1400 and it signaled the start of

a new age.

C

LOSING

I

NON

M

USLIM

S

PAIN

The thirteenth century had witnessed the most dramatic and substantial gains in

the whole Reconquista. Led by three main powers—the monarchs of Portugal, the

united kingdom of Le´on-Castile, and the Crown of Aragon—Christians regained

control of virtually the entire peninsula. The turning point had been the battle of

Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, a huge victory whose success was amplified by the

constant internal fighting of the ’Almohad princes who survived. The Islamic

forces never fully recovered, and the rest of the Reconquest was a slow piecemeal

chipping away at what remained of ’al-’Andalus. The end might have come

quicker, except for the fact that 1212 marked the last time the Christian forces of

Iberia mounted a campaign together or presented a unified front, for as the

Christian-Muslim border moved further to the south the contest to partition the

land to the north grew more insistent. Relations between Le´on-Castile and Aragon-

Catalonia were usually prickly in the extreme. Peter of Aragon’s death in 1213

while fighting Simon de Montfort in the Albigensian Crusade—he fought less in

defense of Catharism than in support of Toulousan independence—possibly

averted a war between the two Iberian powers for control of the peninsula. With

Peter’s death Aragon-Catalonia passed to his young son, James I, the Conqueror

(1213–1276), and tensions between the realms were placed on hold while James

grew to maturity in Montpellier under the care of the Templars there.

By the time James reached the age of majority, the Catalans had turned the

eyes of the nascent Crown of Arago´n eastward into the Mediterranean. James

seized the Balearic Islands in the early 1230s and the Muslim coastal kingdom of

Valencia in the late 1230s. From that point on, the Crown of Aragon concentrated

CLOSINGS IN, CLOSINGS OUT 421

on becoming a sea power; as we saw in Chapter 13, the Catalans became a Med-

iterranean superpower with a confederation of states reaching from eastern Spain

all the way to Athens. This Mediterranean focus left virtually the rest of the Iberian

peninsula to the Castilians and Portuguese. Castile’s Fernando III (1217–1252)

pressed southwestward from Las Navas and took Co´rdoba in 1236 and Seville in

1248. By 1262 the forces of his son Alfonso X (1252–1284) had captured Ca´diz, the

principal port opening onto the Atlantic Ocean. By immediately establishing trade

links with Morocco, Castile signaled an early (though certainly very modest) in-

terest in the idea of expanding via the Atlantic.

5

Castile and Portugal then agreed

to a more or less peaceful partitioning of the western half of the peninsula, an

arrangement that secured Castile’s opening to the ocean and gave Portugal

roughly the borders it still has today.

This progress sounds more straightforward than it was. In reality, fourteenth-

century Spain was filled with dynastic struggles and civil wars that only seem

placid when viewed in relation to the mighty dramas—Muslim versus Christian,

Castilian versus Arago´nese-Catalan—that dominated the thirteenth. The fact is

that after the breaking of Muslim might after 1250 and the more or less permanent

demarcation of borders between Castile and the Crown of Aragon, the Christian

powers in Iberia had more to gain by avoiding conflict with each other. Portugal

set her sights on Atlantic expansion, as the Crown had turned her eyes toward

the Mediterranean, a move that largely left the inland peninsula to Castile. But it

was precisely then that Castile fell victim to internal schisms and wars. The strug-

gles began as a constitutional crisis between the legitimate but autocratic and

detested king Peter the Cruel (1350–1369) and a coalition of nobles led by Peter’s

bastard half brother Henry of Trasta´mara. Both factions looked abroad for support,

and the Castilian problem thus became entwined in the Hundred Years War be-

tween England and France.

6

The conflict continued, like the English-French war,

through several generations and was only brought to an end in 1479 when Isabella

of Castile, the heiress of Peter’s line, married Ferdinand of Aragon, who was the

heir not only of Henry’s line in Castile but also of the Crown of Aragon. Their

union brought all of the Spanish peninsula together into a single state, with the

exceptions of independent Portugal and the tiny Muslim remnant principality of

Granada.

Although small, Granada had a large population since it had absorbed many

of the Muslims who had fled the Christians’ advance. Throughout the Reconquest

Christians had attempted, for the most part, always to keep Muslims on the land

and in the cities, but a large flight was to some extent inevitable as the reconquest

entered its final stages. Being composed largely of refugees, the Granadan popu-

lation developed a reputation for intransigency, a hardheaded determination to

resist the final Christian advance no matter what. With such toughness, they held

out for another two hundred years. Defeat finally came when Isabella and Ferdi-

nand mustered a huge force, crushed the last Granadan army, and received the

surrender of Boabdil, the last Muslim ruler in Spain, in January of 1492—the same

year in which they sponsored Christopher Columbus’ first journey to the New

World, and the same year in which they ordered all the Jews of Spain either to

submit to immediate baptism or to be expelled from the kingdom.

5. The more immediate goal in seizing Ca´diz was to cut off any Moroccan aid to Granada.

6. The English allied themselves with Peter and his successors, which is not surprising when one

considers the principle for which they were fighting against France in the first place—succession to the

throne passing through the female line. The French, predictably, supported Henry and his successors.

422 TWO EPILOGUES

T

HE

E

XPULSIONS OF THE

J

EWS

The Spanish decree of 1492 is the end of the story of Jewish expulsion, not its

beginning. Mass violence against Europe’s Jews had emerged in all its horror with

the First Crusade, when mobs in the Rhine river valley tortured and murdered

thousands of Jewish men, women, and children. Zealous reform movements, like

that affecting the evolution of the crusades, often result in waves of intolerance;

the conviction that one is finally recovering and restoring the Truth can all too

easily lead one to believe that those who reject that Truth stand in the way of the

reform. But the roots of anti-Jewish violence are deeper, as we have seen. To many

people of northern Europe the Jews were parvenus—prosperous Mediterranean

urbanites who were brought north by later Carolingians eager to capitalize on

their commercial connections, financial acumen, and organizational skills. Granted

trade monopolies, tax exemptions, legal guarantees, and the personal protection

of the counts and bishops, the Jews quickly emerged as leading figures in northern

society—and also as focal points for the animosity and bitterness of those less

fortunate. To many, the arrival of the Jews and the collapse of the Carolingian

world appeared as no mere coincidences; the former was surely the cause of the

latter. In this regard, Christian prejudice echoed the prejudice of those ancient

Romans who had connected in their minds the sudden appearance of Christianity

in Roman culture and the pronounced decline in Roman prosperity and peace;

both prejudices resulted in popular persecution.

Over the course of the twelfth century, rumors regularly swept across Europe

that Jews engaged in secret abominable rites whereby they desecrated the Holy

Eucharist and massacred Christian babies, whose blood they either drank or used

in Satanic rituals. Once again, the parallel with early Christian experience is in-

teresting, for the pagan Romans accused the first Christians of the same sorts of

crimes and used such beliefs as justification for persecuting them. A famous early

case occurred in twelfth-century England. The murdered body of a young boy

named William was found in the street in the city of Lincoln, and rumors quickly

spread that the local Jews had killed him and used his blood in a bizarre Passover

ritual (outbreaks of these rumors frequently corresponded with the period of the

Jewish Passover or the High Holy Days, or with the Christian Holy Week). Mobs

raced through the streets pummelling Jews and ransacking their shops. Similar

scenes broke out with some regularity across Europe, but seem to have been most

frequent and violent in France and Germany. The twelfth-century chronicler Ri-

gord relates the following episode about the young king Philip Augustus:

He had frequently heard that the Jews who lived in Paris were accustomed,

every year on Easter Sunday or at some other time during Holy Week, to

sneak into hidden underground crypts and there to kill a Christian as a sort

of contemptuous sacrifice against the Christian religion....Philip inquired

diligently, and when he came to know all too well about these and other

iniquities of the Jews in his forefathers’ days he burned with zeal...and

commanded that all the Jews throughout his entire realm were to be seized

in their synagogues and stripped of their gold, silver, and robes....This was

a foretelling of their expulsion from France, which by God’s will soon

followed.

Money was always a factor in anti-Semitic actions, and at times may have been

the principle one in relation to state decisions about the Jews.

By the end of the thirteenth century—in 1290, to be exact—Edward I expelled

all the Jews from England. His motives were complicated: He himself was deeply

CLOSINGS IN, CLOSINGS OUT 423

in debt to a number of Jewish financiers and banking houses (as he was to many

other, non-Jewish ones as well) and obviously found expulsion of his debtors eas-

ier than payment of his debts. It was certainly a popular move, since English town-

dwellers were not very keen on seeing their tax money go into Jewish purses. And

by expelling the Jews, Edward was also in effect cancelling the debts owed to Jews

by all Englishmen. Those debts were considerable, and widely dispersed. Records

from the Exchequer of the Jews show that most outstanding debts to Jews were

from small landholders—the free farmers—and that farmers feared English land

falling by default into Jewish hands. English law made this eventuality impossible,

but either through well-placed rumor or of their own accord such fears spread

nonetheless and caused widespread panic and a demand for action. Edward’s

popularity increased dramatically as a result of his expulsion order.

Other rulers were quick to take note. In 1292, Philip IV expelled the Jews from

France and ordered the confiscation of all their bank accounts, property, and move-

able goods; the expulsion order was not enforced, though, until 1306. (On a more

local level, Charles of Anjou, the new king of Sicily, had driven the Jews from his

counties of Anjou and Maine in 1288.) Expelled from England and France, the

Jews migrated eastward to Germany where they were grudgingly received in the

hope that their connections might foster an economic revival. But the arrival of

the Black Death in 1348 put an end to those hopes, and many desperate crowds

blamed the Jews for transmitting the disease and lashed out against them in vio-

lence. Jacob von Ko¨nigshofen, a fourteenth-century chronicler, described what hap-

pened to the Jews in Strasbourg in this way:

On Saturday, St. Valentine’s Day 1349, the town council of Strasbourg burned

alive about two thousand Jews on a wooden platform in the middle of the

Jewish cemetery. Those who agreed to be baptized were spared, and they say

that there were about a thousand of these....Every debt that was owed to

the Jews was first nullified, and they had to surrender every surety and piece

of collateral they held for all their loans. Moreover, the town council seized

all the cash that the Jews had in their possession and distributed it to the

urban workers in due proportions. In truth, it was their money that killed the

Jews—for if they had been poor and if the nobles had not been in debt to

them they would never have been put to the flames.

Forced to keep moving, thousands of Jews pressed on to Poland, where they en-

joyed a period of welcome stability and fairmindedness under the rule of King

Casimir III (1333–1370).

The expelled Jews kept migrating eastward because of a basic cultural devel-

opment. Having resided in the north since the ninth century, these Ashkenazic

Jews had developed a distinct culture from the Sephardic Jews of the Mediterra-

nean and felt more at home among their cultural brethren. Inevitably some did

migrate southward into Italy and Spain, but the overwhelming majority preferred

to march eastward, which may say as much about the cultural and religious rift

between the Ashkenazim and the Sephardim as it says about the perceived degrees

of tolerance available. The Mediterranean Jews, while hardly basking in a tolerant

utopia, did fare better, and fared better longer, than their Ashkenzic cousins. The

struggles of the fourteenth century marked the decisive turnaround in Christian-

Jewish relations in the south. Mob violence became increasingly common over the

century, and culminated in a massive outburst of hatred in Castile in 1391. This

drive to separate the religions and cultures that made up medieval society, this

centrifugal effort in state after state to replace the regulated and tension-filled yet