Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

424 TWO EPILOGUES

creative and prosperous heterogenous model of society with a culturally, reli-

giously, and ethnically homogenous world, was another sign that the medieval

way of life was becoming something else.

C

LOSING

I

N

F

OREVER

:T

HE

F

ORCED

C

LOISTERING OF

W

OMEN

R

ELIGIOUS

In 1298, Pope Boniface VIII issued a bull entitled Periculoso, which ordered that

every member of every female order within the Church was to be immediately

and permanently cloistered. These sisters were henceforth to live entirely as monks

did, without exception, physically removed from society in an enclosed Christian

community with no contact with the outside world unless permitted under special

circumstances by the abbess. Explicitly, the bull aimed to protect women religious

from a dangerous world; since the Church could not protect women from men’s

all-too-common inclination to seduce or rape, nor men from women’s all-too-

common inclination to tempt, the least it could do for its members was to protect

them by enclosing them within cloisters. Although Boniface’s language and ar-

gument were somewhat odd, his basic point was rather traditional. From the very

start of the monastic movement in the fourth century, nunneries had been estab-

lished as female counterparts to male monasteries; at the risk of making nonsense

out of the monastic vocation, the Church could no more allow nuns to “live in the

world” than it could allow monks to do so. To be “a nun in the world,” Boniface

suggested, was a contradiction in terms.

As it happened, Periculoso affected nuns rather little. Most of them were clois-

tered already, by choice, and had always been. This fact suggests that the bull was

aimed at a different target altogether: the female lay confraternities, beguinages,

and spiritual communities that had grown up around widely revered mystics. As

early as the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, the Church had been concerned about

the proliferation of new religious orders and sought to stop it by forcing all new

orders to adopt preexisting religious Rules. Enforcement of this decree was incon-

sistent—think of the Franciscans, for instance—but became more common as the

thirteenth century wore on. The difficulty with female lay groups like the beguines

was precisely the fact that they were lay and were therefore outside the adminis-

trative authority of the Church. Worse still, communities like these were becoming

renowned for the extent and frequency of the mystical experiences enjoyed by

their members. The communities’ popularity increased accordingly, usually at the

expense of the mainstream clergy, and there was no way of knowing whether

these mystical revelations were valid or the likely originating point of new

heretical thought. But by exerting the authority granted under the idea of pleni-

tudo potestatis, the popes gradually brought lay groups under the Church’s con-

trol. Within Germany, for example, the beguinages gradually fell under the watch-

ful eye of the Dominicans—with the unexpected result of inspiring a wave of

Dominican mysticism.

The papacy, no matter how plenitudinous its power, could hardly outlaw mys-

tical visions of God; but it could act to protect those who experienced such reve-

lations from misinterpreting them. The best way to accomplish this was to turn

all recognized female orders into nunneries under a recognized rule. This was the

principle goal of Periculoso. It did not force individual beguines to take religious

vows and wear religious habits; those who chose not to were free to “rejoin the

CLOSINGS IN, CLOSINGS OUT 425

world.” But those who chose to remain were henceforth to live in cloistered

seclusion.

The effort to close in on female religious went further. In 1311 at the Council

of Vienne, Pope Clement V issued two new decrees, Attendentes and De quibusdam

mulierem, which complained that many women who had opted to remain in their

orders were not adhering to the new rules or recognizing ecclesiastical authority;

they were wearing the habits and going through the motions but not living the

true life of vowed members of the Church. Consequently, actions were taken that

installed male clergy as heads of all female houses. These new heads were not

resident, but they did possess visitation privileges and were empowered to enforce

canon law over those who were disobedient. In time, the very word beguine came

to have a pejorative sense, one tinged with suspicions of heresy.

There was an economic motive at work as well. Having been established by

private endowments from pious aristocrats and royals, many of Europe’s convents

were quite wealthy. The same was true of male religious houses, of course, but

female nunneries were wealthy in a different way. Generous grants to convents

frequently took the form of endowments set aside for the specific use of an indi-

vidual person or officeholder; thus a Frankish noble might bestow an endowment

specifically for the place held within an abbey by a daughter. These positions,

which continued on through the generations, were somewhat akin to endowed

professorships within a modern university faculty; they created a clear, and some-

times enormous, discrepancy between the lives of endowed and unendowed mem-

bers of a community. At the Benedictine nunnery of Harcourt in England, for

example, the endowment supporting the abbess had increased to such an extent

by the year 1400 that the possessor of the post was able to maintain, among other

luxuries, a separate hunting lodge that staffed four falconers and a stable of over

one hundred hunting dogs. The other sisters at Harcourt frequently starved to

death. By bringing female religious houses under direct Church control, it was

hoped that inequities like this could be ironed out.

Still, it is clear that at the end of the Middle Ages the Church showed much

less willingness than before to allow women the freedom to pursue spiritual ful-

fillment on their own. Female mystics were celebrated and revered, but they had

to pass muster; female lay groups were first eyed with suspicion, then effectively

banned; nunneries that had been essentially independent for centuries were

brought under ecclesiastical jurisdiction. Developments like these do not neces-

sarily show a Church grown intolerant, but they do reflect one grown defensive.

And that alone shows how far the world had changed from its medieval high

point.

S

UGGESTED

R

EADING

Texts

Anonymous. Consulate of the Sea.

Froissart, Jean. Chronicles of France and England.

a` Kempis, Thomas. The Imitation of Christ.

Malory, Thomas. The Death of Arthur.

Robert of Clari. The Conquest of Constantinople.

426 TWO EPILOGUES

Source Anthologies

Marcus, Jacob R. The Jew in the Medieval World: A Source Book, 315–1791 (1979).

The Portable Medieval Reader.

The Portable Renaissance Reader.

Studies

Cahen, Claude. The Formation of Turkey: The Seljukid Sultanate of Ruˆ m—Eleventh to Fourteenth Cen-

tury (2001).

Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe. Before Columbus: Exploration and Colonization from the Mediterranean to

the Atlantic, 1229–1492 (1987).

Guene´e, Bernard. States and Rulers in Later Medieval Europe (1985).

Harvey, L. P. Islamic Spain, 1250–1500 (1990).

Kaeuper, Richard W. War, Justice, and Public Order: England and France in the Later Middle Ages

(1988).

Makowski, Elizabeth. Canon Law and Cloistered Women: ‘Periculoso’ and Its Commentators, 1298–1545

(1997).

Nirenberg, David. Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages (1996).

Phillips, J. R. S. The Medieval Expansion of Europe (1988).

Vryonis, Speros. The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamicization from

the Eleventh to the Fifteenth Century (1971).

427

CHAPTER 20

8

T

HE

R

ENAISSANCE IN

M

EDIEVAL

C

ONTEXT

T

here is little in the great Renaissance of the fourteenth and fifteenth cen-

turies that surprises most medievalists, for despite all the changes that im-

mediately preceded it, Renaissance Europe still appears, in its early stages at least,

as a recognizably medieval place. As thoroughly medieval a character as Roger

Bacon would have felt very much at ease discussing with the fifteenth-century

Florentine humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola the ability of human reason

to harmonize all truths into a single grand vision, or the view that mankind is the

link connecting God and the physical world, or the limitless potential of human

beings to achieve the loftiest goals when aided by a powerful individual will and

God’s grace. Bacon might even have bested the Italian in the debate. The mer-

chants of thirteenth-century Barcelona or Montpellier, were they transported to the

harbor of fifteenth-century Genoa, would certainly have recognized the place—

the same goods, the same basic mercantile and financial practices, many of the

same leading commercial and financial families dominating trade, the same basic

structures and rhythms of daily living, although everything in a clearly diminished

state. If anything, they might have smiled to see their former rival doing so poorly.

And of course a figure like Innocent III would hardly have felt a stranger amid

the Machiavellian politics of the Renaissance papal court.

1

On the whole, it seems

more accurate to describe the early Renaissance as the medieval world with a

difference, rather than as a different world altogether. In some ways, in fact, the

Renaissance, or at least its first few generations, appears to be the culmination of

much of medieval thinking and feeling.

The discovery of the New World in 1492 and the start of the Protestant Ref-

ormation in 1517 shattered once and for all the ideological and cultural unities

that had held, or had purported to hold, medieval Europe together. The vast cen-

tering weight of Catholicism broke into a plethora of Christian interpretations,

each for the time being utterly convinced of its own absolute rectitude; the tug of

the New World shifted the center of western commercial might and political do-

minion to the Atlantic seaboard states of England, the Netherlands, France, Spain,

and Portugal; and the belief in the unity of truth received heavy blows from the

explosion of new religious views, the reordering of the cosmos by experimental

science, and the relativizing pressure of humanism itself. The western world after

the middle of the sixteenth century was a dynamic and exciting place, but it was

no longer predominately medieval in its outlook.

Still, Renaissance life was more than mere climactic medievalism. By 1400, in

Italy and later in the rest of Europe, a new sense of vitality and fresh thinking

1. He would, however, have been genuinely shocked by the sexual shenanigans that took place there

under the Borgia popes.

428 TWO EPILOGUES

was alive, a willingness to be skeptical and embrace experiment, to try to fathom

the world’s increasing strangeness for its own sake. Politically, Italy in the Re-

naissance represented no sharp departure from its earlier experience. Sicily re-

mained a Catalan satellite kingdom, poorer than before but essentially unchanged

in its basic operations; the lower peninsula still answered to ambitious Angevin

monarchs who were less skillful perhaps than those who had come before but

were just as determined to fulfill what they regarded as their destiny; the Papal

State remained under the Holy See’s secular jurisdiction—an aspect of papal

power that proved, for the most part, more consistently effective than its spiritual

claims; and the northern peninsula was still divided into a sprawl of urban prin-

cipalities. Of these Florence, Milan, and Venice still throve as the larger states.

Genoa and Pisa were falling on rather hard times but were still highly influential.

Smaller upstarts like Mantua, Verona, Siena, and Ferrara had also emerged as

forceful entities. The political map, in other words, had altered somewhat in terms

of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the states, but statecraft itself had not

changed significantly from what it had been in the fourteenth or even the thir-

teenth century. Even one of Renaissance politics’ most distinctive features—diplo-

macy as an ongoing, permanent enterprise, with resident professional ambassa-

dors and networks of intelligence gathering and private negotiations—had been

a staple of Mediterranean life at least since the 1290s, and possibly earlier.

E

CONOMIES

N

EW AND

O

LD CIRCA

1400

The state of the European economy at the end of the fourteenth century is difficult

to gauge. War and plague had caused, or had at least catalyzed, so much retrench-

ment and reorganization that historians see profoundly different pictures depend-

ing on which sectors of the economy they are examining. Some emphasize the

bustling sprawl of commercial Venice, which seemed oblivious to economic worry.

According to one contemporary, Marino Sanudo Torselli,

In this city located in an area where nothing at all grows one can find an

abundance of everything. Every commodity you can imagine—but especially

food—is brought here from every country on earth that has anything worth

sending; and here there are plenty of buyers, for everyone here has money.

The Rialto looks like a garden, since there are so many local herbs, vegetables,

and fruits of every variety—and all of them so inexpensive!—on display. It

truly is marvelous to behold.

Keeping up with all this trade required Venice to construct the largest shipworks

in the then-known world, the Arsenal, which at its height employed nearly three

thousand laborers. Other scholars have studied the rental incomes of baronial

landholders in England and found that they maintained a consistent standard of

living, and many even improved their standards, after surviving the initial shock

waves of the Black Death. Manufacturers shared in the profits. By around 1400,

several sites in England (most importantly Coventry, Norwich, Salisbury, and

York) had become centers of actual wool-cloth production; no longer was England

kept in the economically servile status of producing the raw material that others

refined and reaped the principal profits of. Manufacturers and financiers in the

Rhine river valley did well by establishing further trade links throughout the Baltic

and North seas, while merchants further east, along the Danube, erected new

houses, guildhalls, and the occasional small palace with the profits of their trade

with eastern Europe and Russia.

THE RENAISSANCE IN MEDIEVAL CONTEXT 429

But other historians regard these examples as mere islands of prosperity in a

sea of European poverty. They can point to other contemporary witnesses who are

just as wide-eyed in horror gazing upon the common suffering as Marino Sanudo

Torselli was wide-eyed gushing forth about all there was to buy in Venice. Thus

Jean de Montreuil, writing in 1395:

If I were to describe all the evils that have resulted from the war that still

rages [i.e., the Hundred Years War], I would be compelled to quote Virgil:

“What words shall I use to begin?”...

Who could possibly describe the slaughter of so many nobles of high rank,

and even of kings? of the robbery and arson of holy places? the sacrileges,

rape, violence, oppression, extortion, plundering, pillaging, banditry, and ri-

oting? Who could describe (to sum up a multitude of crimes in only two

words) the inhuman savagery of this cruel, horrible war?...

And who, except one whose heart was made of lead, could keep from tears

when describing the cries of so many babies who are fainting and starving

and freezing to death even while at their mothers’ breasts....[Famine is so

widespread] that some infants who are born prematurely are even eaten by

their own mothers—horrific, cattle-like behavior! Truly, it is the madness of

starvation and want that drives people to such desperation....

One eminent historian, Robert Lopez, went so far as to argue that the Renaissance

was actually a period of full-fledged economic depression. He certainly seems to

have been right for the period up to 1400.

Beyond that, it may be more accurate to say that the European economy was

characterized by severe inequities in the distribution of capital. The power of the

guilds and aristocratic voices in royal government ensured that rents and wages

worked to the merchants’ and landlords’ advantage rather than to the farmers’

and laborers’. Capital and political power remained concentrated in the hands of

a finite sector of society, although that sector, since it now included merchants,

manufacturers, and financiers, was considerably larger than just the aristocracy. A

gradual economic recovery began in northern Italy in the early fifteenth century

but did not characterize the rest of the continent until the early sixteenth century;

even then, renewed prosperity was centered in the industrial and commercial

towns. The Renaissance was a poor time to be a common farmer—which is pre-

cisely what most people were. Ironically, the very success of the medieval world

at developing parliamentary institutions of government ensured that wealth re-

mained concentrated in a mercantile and aristocratic oligarchy: Since those were

the sectors of society that comprised the civic representatives, they unsurprisingly

tended to pursue public policies that favored their own positions.

Plague continued to make the world a parlous place. Full-scale outbreaks of

the Black Death occurred on average once every generation until well into the

sixteenth century, and the periods in between were punctuated with smaller, lo-

calized epidemics. These, combined with occasional bad harvests and local wars,

meant that the European population was subject to sudden drastic declines, some-

times as often as every five to six years.

2

In such circumstances inflationary spirals

became commonplace: A failed harvest sent food prices skyrocketing, and the

death of so many workers sent labor costs in the same direction. In general only

those merchants and landowners who had enough capital at hand to allow them

2. Between 1350 and 1450, the city of Florence was hit by a series of plagues, wars, and famines that

resulted in a population loss of 75 percent.

430 TWO EPILOGUES

to ride out the turbulent years survived; in the relatively calmer years in between,

they vied with one another for monopolies to shore up their positions. Thus wealth

continued to concentrate in the hands of a smaller and smaller clique of extremely

wealthy elites; in Italy, the names of some of the wealthiest of these elites have

become familiar: the Visconti, the della Scala, the Sforza, and the Medici families.

Those with capital to spend gave themselves over to luxuriant living and

conspicuous consumption on a fantastic scale. Eastern silks and spices, high-

quality wines (winemaking had progressed to such an extent by this time that

some vintners had begun to establish vintages), sugar and saffron, were all in high

demand. So too were works of art and scholarship, which were aimed to promote

au aura of patronage and public mindedness. In short, the economy of the early

Renaissance resulted in the re-creation of an urban class of elites with much the

same social position as the old Roman curiales, a class that was in fact consciously

emulating that group through its promotion of the individual and civic ethic called

humanism.

T

HE

M

EANING OF

H

UMANISM

Humanism was an outlook on life new to the Renaissance. It was hardly an entire

philosophy or an organized body of thought, although that codification would

follow in later generations. More than anything else, the term described an incho-

ate generational mood, much like the Romanticism of the early nineteenth century.

Humanism began as an attitude of youthful rebellion (can anyone name a first-

generation humanist, around the mid-fourteenth century, over the age of forty?)

against the worst excesses of medieval synthesism, and an insistence on the in-

trinsic value of the specific, the individual, the solitary and unique. In this regard

humanism had much in common with late medieval Franciscanism. Individual

things, persons, or ideas can have autonomous value, independent of their posi-

tions in a grander scheme, the humanists believed, and they ought to be valued

accordingly.

Humanism in the early Renaissance also implied a special dedication to the

liberal arts—the study of grammar, history, literature, philology, and rhetoric (that

is, the studia humanitatis)—for these were the tools that best suited the appreciation

of unique human experience. They were also the subjects that predominated the

curricula of classical Rome, especially in the Republican period, and of Athenian

Greece; the Renaissance humanists placed a high value on classical mores and

sentiments, believing that the ancients had most nearly perfected the philosophy

of loving life for its own sake and appreciating human nature as it truly was rather

than for what it should or could be. Certainly the Greek scholars who achieved

prominence in Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries—figures like Manuel

Chrysoloras, who became the principal tutor in Greek in Florence around 1400—

encouraged this idea. One of the hallmarks of early humanism was the extent to

which its followers embraced the study of classical literature and philosophy. Their

accomplishments were considerable: They recovered large bodies of near-lost clas-

sical writing, in both Latin and Greek, and wrote extensive and sensitive com-

mentaries on what they found. But there were other aspects to their passions as

well. For example, in their zeal to emulate the ancients, many humanist enthusiasts

evinced a desire to “purify” the Latin language, which scholars and churchmen

had been speaking and writing for a thousand years, of its medieval “barbarisms”

and neologisms. The most extreme demanded that anyone who wanted to write

in a pure Latin style could use no word or grammatical construction that had not

THE RENAISSANCE IN MEDIEVAL CONTEXT 431

been used by Cicero. The effect of an artificial reform like this was to kill Latin as

a living language.

3

But these are easy targets. Humanism on the whole was a profoundly moving

phenomenon, as one can see by glancing briefly at the works of Francesco Petrarca

(1304–1374), who is usually considered humanism’s founder. He was born in

Arezzo, near Florence, and grew up in Avignon near the papal palace. While in

grammar school he read and fell in love with Cicero’s writings. He studied law

at the University of Montpellier and spent a few years, unhappily, in that profes-

sion. But when his parents died and left him a comfortable legacy, he gave himself

over to poetry and literary study. He spent the rest of his life gathering, editing,

publishing, and writing commentaries on classical Latin literature, and writing his

own poetry. It is in his poetry, especially, that one can see the difference between

his mode of thinking and that of a poet like Dante. Petrarca too dedicated his

artistic life to the praise of a woman—in his case, a woman named Laura—but

his poetry, while it still engages in a share of idealism, mitigates the ideal by

celebrating the actual woman, her genuine beauty, the specific graceful movement

of her unique body, the gentleness and loving sentiment generated in the poet by

her real physical presence. The point here is not that Dante could not write Pe-

trarca’s type of poetry, nor Petrarca write Dante’s type, but that neither of them

wanted to write the other’s type of poetry. Their aims were different; and that

difference we call humanism. Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) was a disciple of

Petrarca’s. He too began his career as a classical scholar (he claimed to have been

the first person to reintroduce Greek poetry to Italy) but soon moved on to creating

his own imaginative literature. His masterpiece—one he repudiated in later life

because of its supposed immorality—was the story collection known as The

Decameron.

Perhaps the most moving feature of early humanism was the circumstance in

which it was born. Amid all the calamities of the fourteenth century—famine,

plague, economic depression, war, social upheaval, and ecclesiastical division—

the younger generation of writers emphasized a worldview that focused on the

immediate and the particular. The world may have no longer made sense, and the

larger Truths that had been the focus of medieval life may have been drawn into

question, but that did not mean that one had to give in to despair. One still had

one’s life, one’s friends, one’s beloved, one’s books. One could still delight in the

sight of a flowing river at dawn, in the taste of a grilled steak, the sound of a

pleasant melody, or the thrill of a lover’s kiss. Life may be a meaningless broken

jumble, but genuine beauty resides in those shards about one’s feet, so why not

celebrate them? As Petrarca put it in one of his more famous sonnets to Laura:

“Blessed is the year, the month, the week, the day,/the hour, the minute, the mo-

ment, in which I first saw you.” Beatrice, to Dante, was a cosmological miracle;

Laura, to Petrarca, was simply Laura—but that was miracle enough. The human-

ism of the early Renaissance clung to and celebrated such simple glories.

T

HE

C

ANONIZATION OF

C

LASSICAL

C

ULTURE

Why classical literature? The passion for it was hardly new. Latin literature had

been the bedrock of western education since the sixth century; virtually every

educated person in the Middle Ages cut his or her teeth, intellectually speaking,

3. Imagine what would happen to the English language if it was decreed that henceforth no one could

use any word or grammatical construction that does not appear in the Complete Works of William Shake-

speare. How on earth, for example, would one talk about computers?

432 TWO EPILOGUES

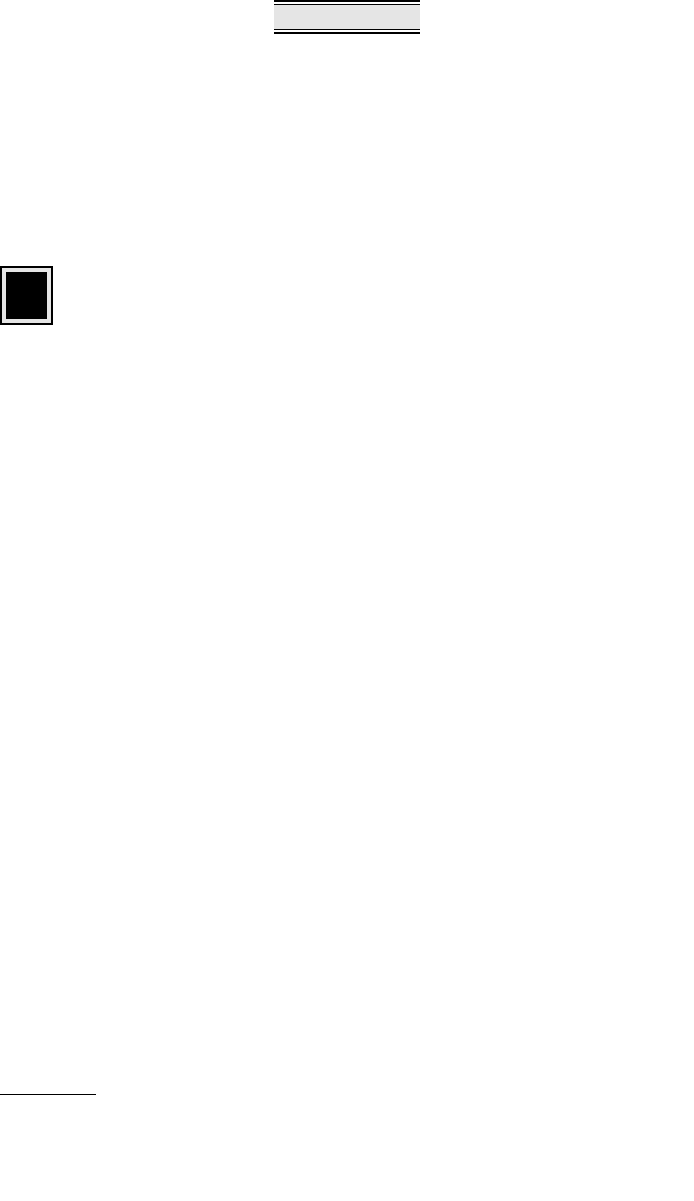

Giotto’s “The Marriage at Cana.” Arena Chapel, Padua. Giotto di Bondone of Florence

was the greatest painter of the medieval era, and the Arena Chapel in Padua, on which

he began to work in 1303, was his first masterpiece. His innovations in perspective,

foreshortening, and portraiture set a new standard in the visual arts, especially in fresco

painting. (Cameraphoto/Art Resource, NY)

on Cicero, Tacitus, Sallust, Virgil, and Ovid. The trivium and quadrivium were

based on the study of the ancients, and from the twelfth century on ancient Greeks

were the intellectual masters of Europe. Medieval science, mathematics, and phi-

losophy were dominated by Plato, Aristotle, Galen, Ptolemy, Euclid, and Hippoc-

rates. To this extent, the Renaissance passion for classical writing is obviously just

a continuation of the medieval norm. What was different about the early Renais-

sance attitude was its sense of the valuation (not the degree of it) this literature

deserved. For most medievals, classical literature was valuable in so far as it

helped to make one a better Christian; the way in which studying Plato served

the purpose of helping one understand Christian mysteries, for example, deter-

mined Plato’s usefulness. But for the early humanists, the classical writers were,

like Petrarca Laura, to be valued in and of themselves, for themselves, and without

reference to a larger purpose. Those larger purposes, after all, were precisely what

the traumas of the fourteenth century had most drawn into question.

THE RENAISSANCE IN MEDIEVAL CONTEXT 433

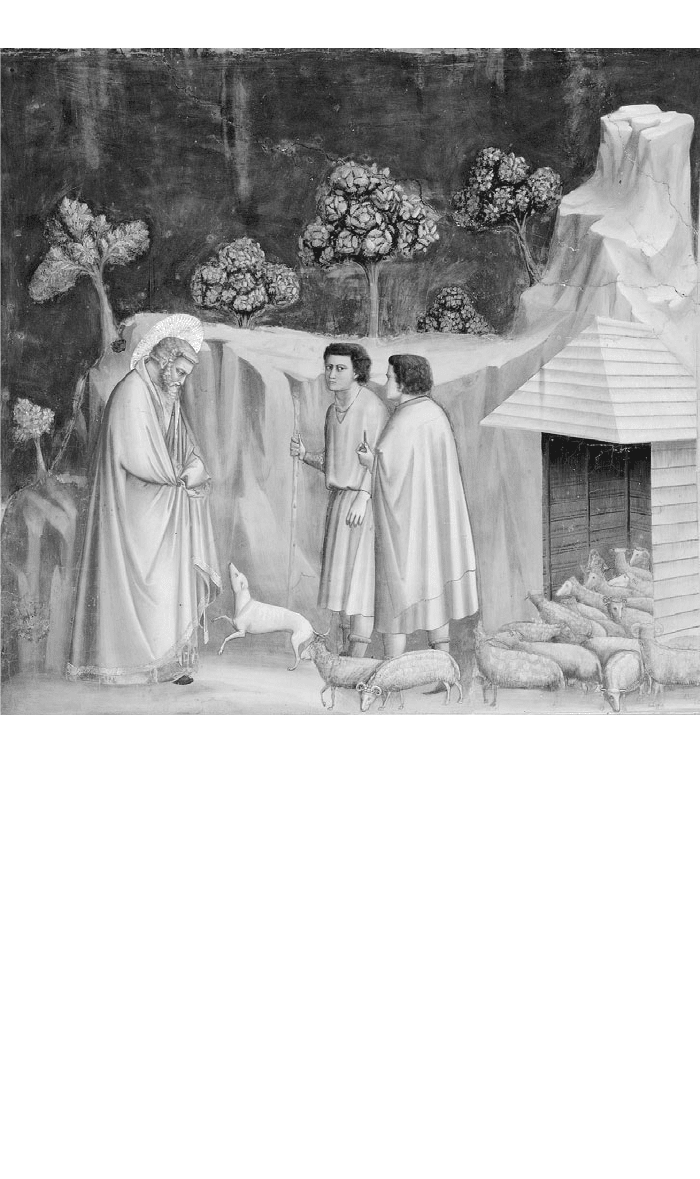

Giotto’s “Joachim and the Shepherds.” Arena Chapel, Padua. The naturalism of Giotto’s

figures and the hanging of their robes shows clearly in this scene of Joachim (the father

of the Virgin Mar y) visiting a group of shepherds. (Cameraphoto/Art Resource, NY)

The achievement of the Renaissance in recovering and reviving the study of

the ancients is considerable—especially of the Latin authors in the early Renais-

sance. A largely self-taught judge and notary named Albertanus of Brescia (d.

1270) had reintroduced the Roman Stoic philosopher and playwright Seneca to

Italy in the thirteenth century, and in the process gave rise to a literary cult; Seneca

proved to be second only to Cicero in significance for the first two generations of

Renaissance humanists. Knowledge of Greek still had not advanced far enough to

spark a meaningful revival of Greek literature until the latter half of the fifteenth

century; nevertheless, enough people before that faked a sufficient knowledge of

Greek to make Greek things fashionable in Italy from the middle of the fourteenth

century. Leonardo Bruni (1370–1444) was the first and greatest Greek scholar of

the early Renaissance; he translated numerous philosophical works of Aristotle

and Plato, and historical works by Plutarch and Xenophon, while also writing a

famous treatise on the education of girls and a Latin history of his native city of

Florence. Many new texts were discovered in monastic libraries across Europe,

also superior texts of older known works. Petrarca himself discovered many of