Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

324 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

And light

䊳

on Alisoun. alights

On hew hire heer

䊳

is fair ynough, In hue her hair

Hire browe browne, hire ye’ blake;

䊳

eyes black

With lossum

䊳

cheere heo on me lough;

䊳

lovely / smiles

With middel smal and wel ymake.

But

䊳

heo me wolle to hire take Unless

For to been hire owen make,

Longe to liven ichulle

䊳

forsake, I shall

And feye

䊳

fallen adown, dead

An hendy hap ich habbe yhent,

Ichoot from heven it is me sent:

From alle wommen my love is lent,

And light on Alisoun.

Nightes when I wende

䊳

and wake, turn

Forthy

䊳

mine wonges

䊳

waxeth wan: So much that / cheeks

Levedy,

䊳

al for thine sake Lovely Lady

Longinge is ylent me on.

In world nis noon so witer

䊳

man wise a

That al hire bountee

䊳

telle can; magnificence

Hire swire

䊳

is whittere than the swan, neck

And fairest may in town,

An hendy hap ich habbe yhent

Ichoot from heven it is me sent

From alle wommen my love is lent,

And light on Alisoun.

Ich am for wowing al forwake,

䊳

worn out with longing at night

Wery so water in wore. Like water in a still pond(?)

Lest any reve

䊳

me my make deprive

Ich habbe y-yerned yore.

䊳

for a long time

Bettere is tholien while

䊳

sore endure pain for a while

Than mournen evermore.

Geinest under gore.

䊳

My unclothed beauty

Herkne to my roun:

䊳

song

An hendy hap ich habbe yhent.

Ichoot from heven it is me sent:

From alle wommen my love is lent,

And light on Alisoun.

Female lyricists expressed their longings as well, as in this excerpt from a trobairitz

(woman troubadour) from southern France:

Handsome beloved, so attractive and fine,

When shall I hold you in my arms?

If only I could lie with you a single night,

and give you a passionate kiss!

Know this:

I would long to embrace you like a wife embraces a husband,

If you would only swear to do everything I ask.

We know a fair amount about the popular dances of the noble courts, but far

less about the dances of the townsfolk and peasants. Dancing was one of the chief

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 325

entertainments in feudal courts from the twelfth century on, despite repeated at-

tempts by the Church to ban the dangerous practice. (Dancing, as everyone knows,

leads to lechery.) Most dances among the commoners were ordinary rounds and

processionals. Carols, which consisted of a closed ring of men and women dancing

around a focal object—a tree, perhaps, or a haystack, a maypole, or a fountain—

were the most popular.

Commoners in the thirteenth century had a wide array of popular games and

sports to select from, to keep themselves entertained. Wrestling was enormously

popular since it cost nothing and required as few as two people; yet whole teams

were often drawn up, often with surprising results, as the following passage from

the history of Roger of Wendover relates regarding a match in 1222.

On the Feast of St. James the townsfolk of London gathered together just

outside the city, at the hospital established by Queen Matilda, to have a wres-

tling match with the inhabitants from the whole district surrounding the city;

in this way they all hoped to find out who was stronger, the townspeople or

the rustics. After they had been at it for a long time, with loud shouts coming

from both teams, the Londoners overthrew their opponents and gained the

victory. Among those who were defeated was the seneschal of the Abbot of

Westminster, and he went away brooding on how he could get revenge for

himself and his companions upon the townsfolk. He finally settled on this

plan: he sent word throughout the whole district for everyone to gather at

Westminster on St. Peter’s Day [for a rematch]...andhepromised the prize

of a ram to whoever proved himself the best [individual] wrestler. In the

meantime, however, he gathered together [from throughout the kingdom] a

throng of powerful and skilled wrestlers, in order that he might ensure his

team’s victory. The Londoners, expecting another victory, came to the match

in high spirits.

When the match began, each side commenced to throw the other about for

quite some time. But then the revenge-seeking seneschal, together with his

rustic companions and provincials, pulled out their weapons and began to

beat and assault the unarmed Londoners, until they caused considerable

bloodshed among them.

Drawings in manuscripts depict games that look remarkably like the modern

games of baseball, tennis, and hockey; card games of great variety; numerous

board games (such as chess—almost exclusively an aristocratic or upper bourgeois

game); and the unsurprising array of balls, dolls, wooden swords, and other bric-a-

brac of childhood.

The point of this is simply to remind us (as we all need reminding on occasion)

that medieval people were not only soil-tilling serfs and shop-working artisans,

busy maids, praying monks, fighting knights, patient wives, scheming princes, and

crouched scribes. They sang and danced, they had favorite sporting teams, they

enjoyed theatricals, they had private likes and dislikes. They were fully human,

fully flawed, fully complicated—and therefore all the more interesting to study.

S

UGGESTED

R

EADING

Texts

Aquinas, St. Thomas. Summa contra gentiles.

———. Summa theologica.

326 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

Bacon, Roger. Opus Majus.

St. Bonaventura. The Mind’s Road to God.

de France, Marie. Lais.

de Meun, Jean. Romance of the Rose.

de Troyes, Chre´tien. Complete Romances.

Source Anthologies

Bogin, Meg. The Women Troubadours (1976).

Bosley, Richard N., and Martin Tweedale. Basic Issues in Medieval Philosophy: Selected Readings

Presenting the Interactive Discourses among the Major Figures (1997).

Doss-Quinby, Eglal, Joan Tasker Grimbert, Wendy Pfeffer, and Elizabeth Aubrey. Songs of the

Women Trouve`res (2001).

Flores, Angel. An Anthology of Medieval Lyrics (1962).

Hanning, Robert, and Joan Ferrante. The Lais of Marie de France (1978).

Studies

Baldwin, John W. The Scholastic Culture of the Middle Ages, 1000–1300 (1971).

Bony, Jean. French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries (1983).

Calkins, Robert G. Medieval Architecture in Western Europe from AD 300 to 1500 (1998).

Colish, Marcia L. Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition, 400–1400 (1997).

Cross, Richard. Duns Scotus (1999).

Drury, John. Painting the Word; Christian Pictures and Their Meanings (1999).

Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain. The Cathedral: The Social and Architectural Dynamics of Construction

(1994).

Jaeger, C. Stephen. The Origins of Courtliness: Civilising Trends and the Formation of Courtly Ideals,

939–1210 (1985).

Keen, Maurice. Chivalry (1984).

Keiser, Elizabeth B. Courtly Desire and Medieval Homophobia: The Legitimation of Sexual Pleasure in

“Cleanness” and Its Contexts (1997).

Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages (1990).

Kolve, V. A. The Play Called Corpus Christi (1966).

Lacy, Norris J. Reading Fabliaux (1993).

Muscatine, Charles. The Old French Fabliaux (1986).

Paterson, Linda. The World of the Troubadours: Medieval Occitan Society, ca. 1100–ca. 1300 (1995).

Radding, Charles M., and William W. Clark. Medieval Architecture, Medieval Learning: Builders and

Masters in the Age of Romanesque and Gothic (1992).

Southern, R[ichard] W. Robert Grosseteste: The Growth of an English Mind in Medieval Europe (1992).

Williamson, Paul. Gothic Sculpture, 1140–1300 (1995).

Woolf, Rosemary. The English Mystery Plays (1972).

Yudkin, Jeremy. Music in the Middle Ages (1989).

327

CHAPTER 15

8

D

AILY

L

IFE AT THE

M

EDIEVAL

Z

ENITH

D

espite the idealizing visions of the theologians, political theorists, archi-

tects, artists, and scientists, medieval society continued to be, at street level,

remarkably dynamic and changeable. A monolithic medieval society never in fact

existed; regional and local differences in social organization, religious practices,

laws and currencies, dress and diet norms, dialects, prides and prejudices, re-

mained strong. What united the medieval worlds, more than anything else, was

the simple desire to create a unity, an eagerness to think in collective instead of

individualistic terms and to define the essence of things by their relation with

other things. This desire both preserved individuality and fostered a sense, how-

ever vague or indirect in practice, of cohesion. But it would be a mistake to ex-

aggerate the degree to which such organic cohesion was actually achieved in daily

life. More people in medieval Europe believed in unity than actually lived it.

Europe was now a surprisingly crowded place. Its population around the year

1300 was somewhere between seventy five and one hundred million, easily twice

and perhaps even three times what it had been around the year 1000. Proportion-

ally, the urban population was clearly in the ascendant: a handful of megalopolises

existed—Constantinople, Milan, Venice, and Palermo all had populations of a hun-

dred thousand or more; at least a dozen cities like Barcelona, Cologne, Mainz,

Florence, London, Marseilles, and Paris had between thirty and seventy thousand.

Even rural villages were growing in size. A farming town of four thousand people

was not uncommon. As cities and villages grew, they tended to clear the surround-

ing countryside since they needed the lumber for constructing and heating their

buildings. Hence cities were not only larger and more numerous in an absolute

sense, but they also stood out more sharply on the landscape. A traveler could

eye most cities at a distance of several miles, especially their towering cathedrals.

In order to support this increased population some changes in the land became

necessary. Medieval engineers perfected the methods of draining fens and marsh-

land. In northern Italy a vast network of canals, dams, embankments, and reser-

voirs helped control the runoff waters of the Alpine heights. In Spain the ancient

Roman irrigation systems were revived. The people of the Low Countries con-

structed their so-called Golden Wall, a chain of breakwaters and dikes from Flan-

ders to Frisia in order to help reclaim land from the Zuider See. Half of what is

today Holland, plus about a fifth of today’s Belgium, used to be underwater; the

land literally came to light thanks to medieval engineers and workers, and the

burghers who paid for the project.

The urbanization of Europe had far-reaching consequences. Cities, after all,

are more than sites of commerce and administration. They are social organisms

that themselves promote further organization; most city dwellers, then as now,

maintained membership in a variety of other social networks and local linkages:

328 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

parish churches, trade guilds, neighborhood assemblies, ethnic or religious ghet-

toes, local schools, religious confraternities and prayer groups, sports teams, or

even the gathering of regulars at the local tavern. The creation of these commu-

nities demanded and catalyzed change. For example, the needs of urban life—

contracts, receipts, deeds, government reports, judicial summonses and decisions,

letters and libraries—tend to foster a need for, and therefore an increase in, general

literacy. This need both contributed to and resulted from the proliferation of

schools in urban centers. But cities also offer the opportunity of anonymity; most

readers of this book will know what it is like to feel alone in a crowd of several

thousand people. So for medieval townsfolk, and for new immigrants to the cities

anonymity was a new sensation indeed, one that elicited fundamental questions

of identity and position. The conception of one’s own identity changed signifi-

cantly once one was freed, for good or ill, from the relationships that defined one’s

identity and social role in a smaller and rural setting. As a consequence of this

anonymity, and the general proliferation of literacy, cities in the High Middle Ages

witnessed the otherwise inexplicable rise in popularity of the genre of autobiogra-

phy. St. Augustine may have invented it in the fifth century with his great Confes-

sions, but no such analogous work was even attempted, that we know of, until the

twelfth century. Peter Abelard’s History of My Misfortunes seems to have revived

the form; in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it became surprisingly

popular.

As laboratories of cultural interaction, cities created the atmosphere for testing

social assumptions and traditional behaviors. Many gender roles were questioned;

some were changed. Ideas and technologies passed from one group to another.

But resistance to such changes also ran strong, and in a backlash reaction medieval

Europe became obsessed with the notion of labeling and identifying people so that

one knew who was one dealing with. Ethnic and religious groups were increas-

ingly forced to wear identifying badges—Jews, for example, had to sew circular

badges of yellow cloth on their outer garments—but the passion for identifying

people went beyond religion and was something larger than mere prejudice. Bak-

ers wore certain kinds of hats; priests wore clerical collars; students wore academic

robes; members of individual guilds had signifying collars, badges, robes, and

rings to identify their trade, pilgrims carried staves and rucksacks that betokened

their status. Statutes called sumptuary laws laid down strict rules for dress stan-

dards that differentiated the classes: The well-to-do wife of an international mer-

chant, for example, might be allowed to wear a silk garment with twelve silver

buttons and an embroidered hemline two palm-widths from the ground, but the

wife of a modest tavern-keeper, regardless of how much disposable cash she had,

had to resign herself to a woolen garment with a half-dozen brass or even wooden

buttons and a plain hemline four palm-widths from the ground.

1

Everyone had a

pigeonhole and had to live in it. But even here the idea was less to atomize society

than to bind it together by having everyone play their appropriate role and not

pretend to anything else. What medieval society, consciously or not, aimed for was

a vision of civilization that was best defined, in a very different context, by the

1. An example from the municipal laws of London (1281): “No woman of the city may henceforth

enter the marketplace, walk on the king’s highway, or leave her house for any reason, wearing a hood

trimmed with anything other than lambskin or rabbitskin—upon penalty of the sheriff’s confiscating

that hood—unless that woman is one of the [noble] ladies entitled to wear fur-trimmed capes (the hoods

of which they may trim with whatever fur they deem proper). This law is enacted because many shop-

girls, nurses, servants, and women of loose morals do now go about bedecked in hoods trimmed with

squirrel-fur or ermine, as though they were in fact true ladies.”

DAILY LIFE AT THE MEDIEVAL ZENITH 329

twentieth-century poet W. H. Auden: Civilization, he said, is measured by “the

degree of diversity attained and the degree of unity retained.” That, above all,

was the goal of the medieval worlds, and it was best attained in the cities of the

thirteenth century.

E

CONOMIC

C

HANGES

The most important innovations in economic life at the medieval zenith were the

development of the guild system and the banking industry. A guild was analogous

to a modern trade association, if one is talking about the artisanal crafts, or a cartel,

if one is discussing the merchants who sold the craftsmen’s goods on the regional

or international market. Merchants were the first to organize—a guilda mercatoria

existed at Saint-Omer, in far northern France, by the 1090s; artisanal guilds did

not become common until after 1200. To survive in a world where robbery and

rogue barons ruled the day, merchants took refuge in numbers and banded to-

gether against extortion; they also came together for mutual protection when trav-

eling. Whatever the spark that ignited their formation, guilds proliferated with

exceptional speed throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, from the Med-

iterranean to the Baltic and from England to the borders of Byzantium.

2

Large

cities like Cologne, Lu¨beck, Milan, Paris, or York had dozens of guilds apiece,

often one for each major manufacture. Once established, guilds set norms for com-

modity pricing, the quality, quantity, and means of production, and the wages to

be paid to the various workers who produced the goods. The earliest guilds were

usually comprised of all the merchants in a given city, regardless of the commod-

ities they dealt in, and they began to form in the late eleventh century.

3

Member-

ship in an urban guild amounted to a general business license; the development

of separate guilds for individual industries occurred over the course of the twelfth

century, each with its own statutes, privileges, guild hall, and governing proto-

cols—although it was common to find many of the same merchants on the rolls

of more than one guild.

As economic institutions, guilds had considerable influence over society. Craft

guilds controlled entry into their industry by setting strict regulations for awarding

apprenticeship contracts, advancing workers to journeyman status, and recogniz-

ing craft mastery and admission into the guild. Heavy fees were required along

the way, and even heavier penalties were meted out to those who scoffed at the

regulations. Merchant guilds, by contrast, required proof of no particular technical

skill like the artisanal organizations, but admission was conditional on any number

of factors that changed from time to time and from place to place: Wealth, family

connections, social standing, ethnicity, political affiliation, and commercial contacts

all figured into the calculus.

Guilds served both commercial and social functions. Commercially, they acted

as loose monopolies controlling the economic life of a city; in this guise they came

to play highly influential, and frequently determinative, roles in urban politics. On

a social level, guilds became organized charitable institutions that helped to es-

tablish schools and hospices, provide food for the poor, assist in evangelical activ-

ity, and to care for guild members who fell upon hard times. The rules of the wine

2. German and Scandinavian guilds commonly went by the name of hansas.

3. There were precursors to the guilds in the religious confraternities (called caritates) of the Carolingian

period. These were sworn associations of laymen who dedicated a portion of their lives and livelihoods

to the notion of religious community but without taking full monastic vows.

330 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

and beer merchants’ guild at Southampton in the thirteenth century, for example,

established that

whenever the guild is in session the lepers at [the hospital of] La Madeleine

shall receive in alms from the guild eight gallons of ale, as shall the sick in

[the hospitals of] God’s House and St. Julian’s. The Franciscans shall receive

eight gallons of ale and four gallons of wine; and sixteen gallons of ale shall

be distributed to the poor from whatever spot the guild meets at....Ifany

guild member should fall into poverty and cannot pay his debts, and if he is

unable to work and provide for himself, he shall receive from the guild one

mark [of silver] every time the guild meets in session, in order to relieve his

suffering.

Admission into merchant guilds was carefully screened; applicants had to be peo-

ple of good standing and repute in the community, had to meet basic income

standards and pay regular dues. Inheritable membership kept many cities’ guild

memberships fairly constant and left trade in the hands of a coterie of highly

influential families.

Artisanal guilds were more fluid. Individual craftsmen like blacksmiths, coo-

pers (barrel makers), carpenters, tailors, stonemasons, or glassblowers would take

on apprentices to whom they taught their crafts. Urban youths began their ap-

prenticeships quite early in life—often as young as eight years of age, depending

on the trade—and lived in the master’s home and worked in his shop until they

had learned the fundamental skills needed for the job. This education commonly

took seven years. Having completed his apprenticeship, a young worker then

moved on to journeyman status. At this level he was now a paid employee with

greater legal rights and social standing; a journeyman usually worked for his mas-

ter for several more years, refining his skills and forming the business connections

that would ultimately help him set up his own shop. (Needless to say, many

people never made it out of journeyman status, rather like an academic who never

becomes a full professor.) In theory, artisanal apprenticeship was available to any-

one who convinced a master of his potential and could come up with the money

to pay for his room and board and instruction. Movement across class lines was

therefore possible, and a former serf could rise, if he was very lucky, through the

rank of journeyman to master craftsman. Few people of low origin, however, were

able to break into the merchant ranks.

Women and girls were indirect beneficiaries of the apprenticeship system, or

at least they could be. Since most town dwellers lived and kept shop in the same

building, an artisan’s wife, sisters, daughters, or nieces who lived with him could

learn his techniques just by watching him teach his apprentices. Women generally

did not have the legal power to go off and start their own businesses, but they

could inherit them. And since townsmen in the Middle Ages tended to take young

wives—sometimes as young as twelve or thirteen, in order to take maximum ad-

vantage of child-bearing years (although such cases were extreme even by medi-

eval standards)—many urban women found themselves running shops and busi-

nesses inherited from their fathers or dead older husbands. In some regions,

women, if they knew a particular trade like ale-brewing but happened to marry

a man who followed a different trade, could legally open their own shops and

run them themselves, provided that their husbands approved of the venture. By

the start of the fourteenth century, some trades in fact were dominated by women

ale-brewing and tavern-keeping, silk-spinning, and haberdashery, for example.

Women practiced many trades and were full-fledged members of many guilds.

DAILY LIFE AT THE MEDIEVAL ZENITH 331

Female artisans were found most frequently in textile guilds (as weavers or cloth-

finishers, usually), in brewing, in candle-making, and in baking guilds. Widows

could usually inherit their husbands’ guild memberships, but membership was

often nullified if a woman remarried. In Paris alone by the end of the thirteenth

century, women held memberships in 80 of the city’s 120 trade guilds, and 6 of

those 80 were designated as female-only guilds.

With the rise of guilds, medieval cities became centers of industrial production

for the first time; prior to roughly 1200, most craft work and manufacturing was

done domestically, with each family producing most of what it needed in terms

of material goods. Some small-scale production of goods for general sale had al-

ways been present, but organized mass production of specialized commodities by

individual businesses was a new development. It is likely that industry of this

sort was the creation of the merchants who wanted to find a way of guaranteeing

the supply of certain commodities for which they had markets abroad. The raw

materials for those industries did not have to exist locally: Flemish textile mer-

chants, for example, purchased raw wool from England and brought it to the

weavers in Flanders, and then sold the woven cloth on the international market.

In this way the merchants made healthy, and at times enormous, profits since they

owned the commodity from start to finish; the craftspeople did not own the goods

they produced in their shops, but only worked on them in return for a set wage

paid by the merchants.

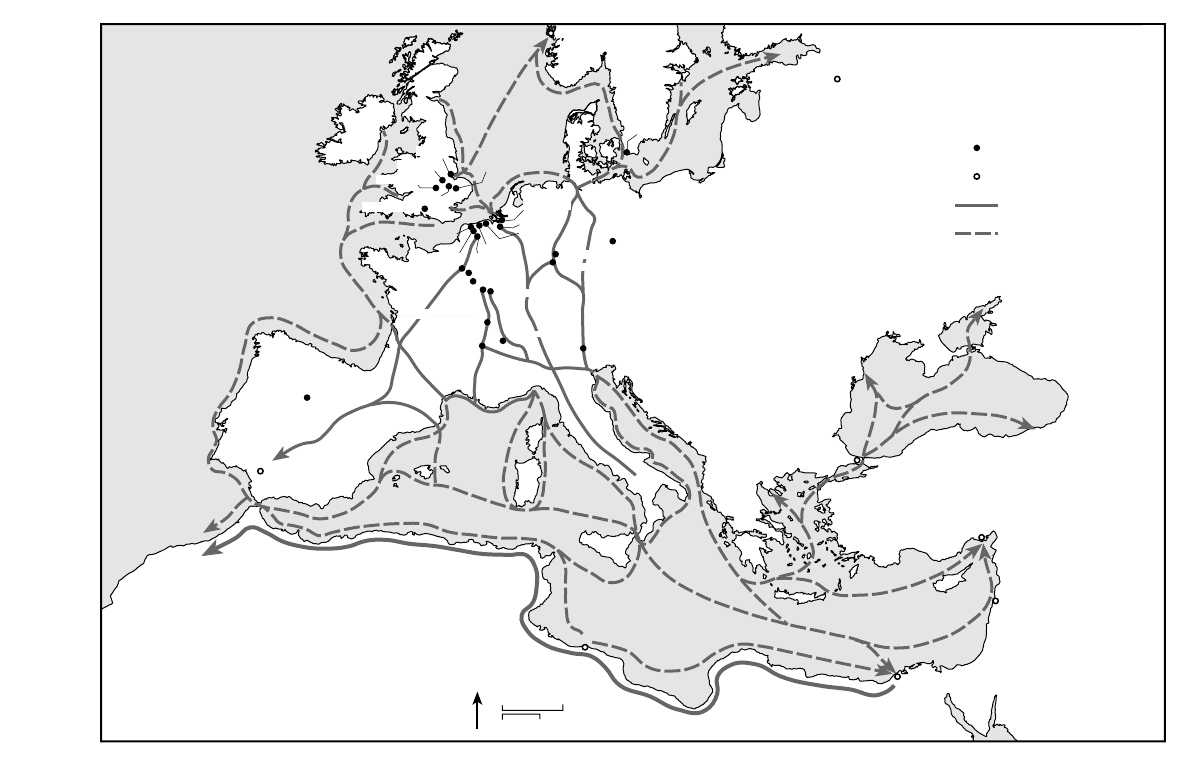

In order to reduce the cost of transporting goods on the international market,

merchants in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries developed the institution known

as the fair. These were large-scale commercial emporia established throughout Eu-

rope where merchants would bring their goods to sell on the wholesale market.

Most fairs lasted only a week per year, but the largest ones met annually for as

many as three weeks. Many merchants traveled in a regular circuit from fair to

fair instead of trekking laboriously from city to city. In order for a fair to be suc-

cessful, it had to be held at a site which had a suitable infrastructure for the

transport of enormous quantities of goods; hence, fairs most commonly lay along

navigable waterways or at the intersection of major trade routes. The most famous

medieval fairs were those held in the county of Champagne, just east of Paris.

Four locations in Champagne were fair sites, which meant that the county annually

staged at least four, and sometimes as many as six, fairs per year, which generated

enormous sums of tax and toll revenue for the local count. The danger of carrying

the large sums of money needed for this sort of commerce led to the development

of bills of exchange or letters of credit; these functioned very much like our mod-

ern checks, although they were not necessarily drawn upon banks. Groups like

the Templars, before their dissolution in the early fourteenth century, served as

financial service units, holding depositors’ funds and settling accounts. Individual

moneylenders and currency changers also played an important role here. Jewish

merchants often specialized in finance of this sort, since they were obviously ex-

empt from the Church’s strictures against charging interest on loans. Christians

and Jews bought from and sold to each other openly in the markets, but there

were strong objections, from religious leaders on both sides, to their entering joint

commercial enterprises as business partners. Such partnerships did happen with

some frequency nevertheless.

The development of banking techniques and institutions was no less impres-

sive. Banking—the word comes from the Latin banca which denoted a money

changer’s “bench” or “counter”—has an obscure origin. The principal functions

that we associate with banking (primarily deposit-holding, moneylending, and

332

0

200 Miles

0

200 Kms.

N

E. McC. 2002

Medina del

Campo

Lyon

Geneva

Frankfurt-am-Main

Antwerp

Bruges

Lille

St. Denis

Troyes

Chalons-sur-

Saône

Scania

Leipzig

Friedberg

Lagny

Provins

Bar-sur-Aube

Bergen-

op-Zoom

Mesen

Torhout

Ypres

Boston

Stamford

Northampton

Winchester

St. Ives

Bury St.

Edmonds

Bozen

ATLANTIC OCEAN

North

Sea

Baltic Sea

Adriatic Sea

Black Sea

Tyrrhenian

Sea

Ae gean Sea

MEDITERRANEAN

SEA

Novgorod

Alexandria

Beirut

Tripoli

Seville

Bergen

Constantinople

Ayas

European Fair

Other Trade City

Land Route

Sea Route

European Trade

First trade routes

DAILY LIFE AT THE MEDIEVAL ZENITH 333

currency exchange) had all been performed by individuals on an ad hoc basis in

earlier times, and historians agree that true banking began only when two or more

of these activities became the normative functions of a settled capital concern made

up of a sworn association of financiers—a guild of the moneyed, in other words.

At this point agreement ends, since historians see the confluence of these elements

in different places and at different times. By definition, however, banks require

money, and western Europe did not develop a money economy until the late tenth

century or even later. Since the first areas to develop money economies were the

Mediterranean city-states and the German empire, it is likely that the origins of

banking should be sought in either of those areas. The southern cities probably

engaged first in currency exchange and deposit-holding, while the empire may

have had the lead in combining moneylending and exchange; this conjecture is

based on the fact that the empire experienced a sudden influx of specie under the

Ottonians and could draw upon their sizable Jewish population to provide loans

and serve as contacts with foreign merchants, whereas the southern cities reignited

commercial networks that had merely gone into abeyance.

The popularity of the commercial fairs gave further impetus to the develop-

ment of banking, for funds had to move frequently and often over long distances

in order to meet obligations. The ability to deposit money in a bank in one city,

only to draw on that amount from another office of that bank in another city, eased

the problem of transferring funds considerably. Certain cities earned reputations

as major financial centers: Bruges, Cahors (in southwestern France), and Florence

were three of the most prominent. But by the thirteenth century, most major cities

had within their confines either banks of their own or offices of foreign banks.

Many of these banks had quite fantastic sums of capital at their disposal: Loans

from the Riccardi bank in the city of Lucca, for example, kept the government of

England afloat for nearly twenty years during the reign of Edward I (1272–1307).

P

EASANTS

’L

IVES

The overwhelming bulk of the medieval population continued to work the land.

After the proliferation of collective manors in the tenth and eleventh centuries,

relatively few major structural or technological changes took places in rural life in

the twelfth and thirteenth. The agrarian scene was not altogether static, however.

In order to provide more food for the urban and international markets, manors

across Europe grew significantly in size. Since there were no major advances in

farming methods to increase the yield per acre of farmland, landowners chose

instead to produce more farmland: They felled forests, drained marshlands, and

brought meadows under the plow. This clearing meant more work for more peas-

ants, and the populations of manors and villages increased accordingly. But the

rhythms and workings of daily life continued on much as they had done before—

with at least two important changes.

In England there was a pronounced movement away from lease farming,

which had become quite common over the course of the twelfth century. Peasants

had frequently become rent-payers, commuting their manorial services into fixed

rents that they owed to their landlords in return for the right to work the landlords’

lands, use his tools and animals, and appeal to his authority for the settlement of

disputes. By the start of the thirteenth century however, large numbers of land-

lords decided they could make greater profits by commuting their tenants’ rents

back into required services and selling their manors’ produce directly on the market