Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

314 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

Lothar’s Cross. Tenth century. This ceremonial cross, made by

craftsmen in Cologne but now housed in the cathedral at Aachen, is

a fine example of medieval metalwork, ivor y work, and jewelry-

making. (Erich Lessi ng/Art Resource, NY)

dynamism of the new style. A Gothic cathedral, always the largest building in a city

and the first building visible to one approaching the city, represented a summation

and harmonization of artistic genres and expressions. It comprised architecture,

sculpture, painting, drama (in the form of the Mass), and music. It was a living art

work, a complex vision whose majesty derived from its harmonization of its com-

ponent parts. Each cathedral was in its way a free-standing summa theologica.

The chief characteristics of Gothic style were the pointed arch, ribbed vaulting,

and the flying buttress. The pointed arch dispersed the weight and thrust of the

archway in a new way and thus posed an engineering problem, but it achieved a

pleasing new effect—a heightened sense of verticality and openness. The intro-

duction of the ribbed vault—ceilings composed not of solid archways of stone but

of a network of arched stone ribs that fanned out over the aisles, with the areas

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 315

Interior of Sainte-Chapelle, Paris. The stained-glass windows

of the Sainte-Chapelle (1246–1248) are a fine example of the

vibrancy of Gothic art. The pointed arches and ribbed

vaulting of the Gothic style can also be seen clearly.

(Giraudon/Art Resource, NY)

between the ribs filled with plaster—dramatically decreased the weight of the roof

and made it possible to raise the churches’ overall height and to introduce still

more and still larger windows. But while the ribbed vaults solved the problem of

weight, they helped little with the lateral thrust of the heightened walls and roofs.

Thus the flying buttresses—external supports strutting outward from the walls at

regular intervals, like the legs jutting out from the torso of a caterpillar—resolved

this difficulty. It took several decades for church builders to perfect these new

methods and to bring them into aesthetic balance, but once they had done so the

effect was astonishing. Gothic cathedrals like those at Amiens or Reims in France

shimmer with light and color, and the strong vertical lines established by the raised

roofs, pointed arches, and tall, slender columns have the effect of drawing one’s

spirit upward toward heaven, while heavenly music rings down upon one from

316 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

Choir of Gloucester Cathedral. A example of florid late Gothic

style, the choir of Gloucester Cathedral (1337–1357) is a

beautifully controlled riot of color, light, vertical thrust, and

fanciful vaulting. (Scala/Art Resource, NY)

the elevated choirs. Combining as it does such an array of arts, each so wonder-

fully realized and all placed in such harmony with one another, a Gothic cathedral,

in the course of celebrating a High Mass, continues to offer an unparalleled spir-

itual and aesthetic experience.

S

CIENCE AND

T

ECHNOLOGY

Scientia meant something different in the Middle Ages from what science means

for us today. Our modern English word made its first appearance only in 1340,

when it had the simple meaning of “knowledge.” But scientia implied something

larger and grander. It evoked images of God’s magnificence and the harmony of

His creation. Scholars used to translate scientia as “natural philosophy,” a term

that was intended to rouse the notion of systematized knowledge—and it is a

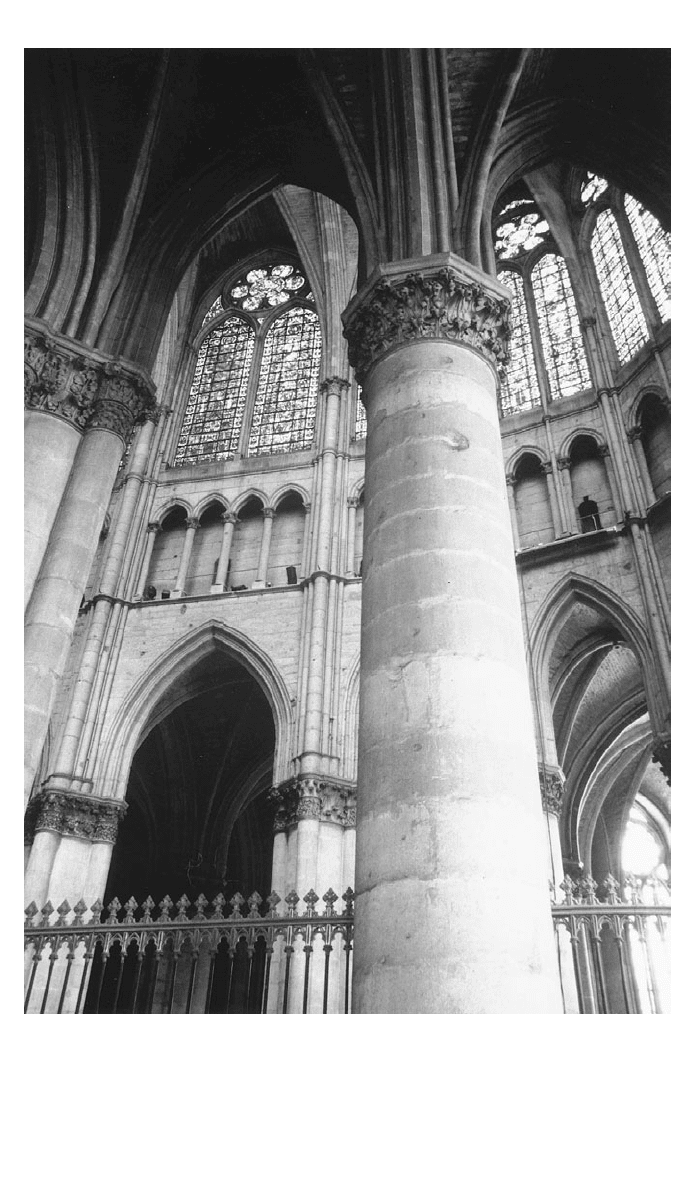

Reims Cathedral. The pointed arches and fan-ceilings of the Gothic style, when

coupled with the use of stained glass windows, as shown in this example from

Reims Cathedral, created drmatic effects of upward thrust and brilliant light. The

style both evokes and elicits an emotion of spiritual exaltation and contrasts

sharply with the staid majesty of the Romanesque. (R. G. Calkins)

317

318 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

pretty good rendition. What medieval “scientists” discovered were individual

truths or laws, whether in the areas of biology, chemistry, medicine, or whatever,

but the implication was that these discrete discoveries were merely parts of a larger

conjectured whole, a supreme blueprint that structured and balanced the cosmos.

The great “scientists” of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries made im-

portant individual discoveries and helped to promote the notion of the Grand

Design of the universe. This notion was to be the dominant Western attitude until

the troubling scientific dissolution of the early modern period.

The catalog of achievements in medieval science and technology is impressive.

The fields of anatomy, astronomy, botany, chemistry, geography, kinetics, linguis-

tics, magnetism, medicine, oceanography, optics, pharmacology, and zoology, to

name only a few, all enjoyed significant advances in their theoretical understand-

ing and practical application. At the level of technology, medieval engineers and

inventors developed eyeglasses, astrolabes, mechanical clocks, and magnetic com-

passes. It is difficult to answer the question “what did people in the Middle Ages

really know?” in terms of science, because there is no easy way to tell how widely

spread any given bit of knowledge might have been. In terms of astronomy and

cosmology, for example, almost every university-educated person in the thirteenth

century knew that the earth was round, but the majority of town dwellers and

rural workers probably did not. The prevailing popular cosmological model pos-

ited an immobile earth at the center of the universe, with all the planets and non-

fixed stars revolving around it in concentric circular orbits; but the theory of a

rotating earth was also extremely well known (it simply was not regarded as

proven). Medical science was hampered by cultural and ecclesiastical restraints on

dissection, although by the thirteenth century the leading physicians at schools

like the University of Montpellier were known to perform occasional dissections.

Figures like Arnau de Vilanova (d. 1311) wrote numerous treatises on the various

organs and their functions.

The two most important scientific figures of the thirteenth century were both

Englishmen: Robert Grosseteste (1168–1253), the first Chancellor of Oxford Uni-

versity, and Roger Bacon (1214–1292), who was one of the first, and certainly one

of the most outspoken, champions of the experimental method as the key to ad-

vancing scientific knowledge.

Grosseteste was born into a poor Suffolk family and received an excellent

education through England’s network of provincial patronage, rather than through

formal schooling. Wealthy patrons eager to show their sophistication frequently

retained scholars on their estates, providing them with libraries, equipment, and

above all the leisure time needed to educate themselves and each other. Grosseteste

was fortunate enough to receive such patronage and enjoy the company of other

self-taught scholars. His first big break came when he entered the household of

the bishop of Hereford, under whose guidance he added a strong foundational

knowledge of law and medicine to his already strong background in science. Ul-

timately, Grosseteste went on to the University of Paris to earn his degree in the-

ology; sometime around 1214 he returned to Oxford and took up residence as

University Chancellor, a post he held for about a decade. He lectured, broadly and

brilliantly, on topics as varied as astronomy, linguistics, music, and optics, and

earned a reputation as a preacher as well. Like many self-taught people who had

to struggle for years for his education, he had little patience with students who

did not take their studies seriously. Increasingly drawn to the Franciscans whom

he found to be consistently the best scholars at the university, he devoted himself

to preaching and lecturing to the friar-scholars about five years after arriving in

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 319

Oxford. (He never actually joined the order, however.) In 1235 he was appointed

bishop of Lincoln. His single best-known discovery was in the field of optics: By

refracting light through a lens, he produced the first accurate description of the

color spectrum and the first solid explanation of the cause of rainbows.

Grosseteste was a serious-minded, earnest scholar and preacher; but his stu-

dent Roger Bacon was a phenomenon, a brilliant ambitious scientist with a prickly

contrarian’s personality. In fact, he was an intellectual bully who never met a man

he could not offend. Bacon came from a wealthy non-noble family that could

afford to give him an education. He boasted later in life that prior to becoming a

Franciscan in 1252, he had spent over two thousand pounds (an enormous sum)

on books. He studied at Oxford with an eye to winning a doctorate in theology,

but he felt that theology—the “Queen of Sciences”—could only be done properly

if one had first mastered all the fields of philosophy and science, and he spent so

long in what he considered essential preparatory work that he never got very far

in theology itself. He taught for a while at Oxford, then moved to Paris for more

advanced work. Like many scholars of the age, he was a passionate student of

Aristotle, but Aristotle was still frowned upon by the conservative masters of Paris.

Bacon had virtually no patience with anyone with whom he disagreed or whom

he regarded as an inferior intellect—which left him with very few friends. His

students, though, loved his brash brilliance. He was an enormous success as a

lecturer; unlike most university teachers he encouraged his students to ask ques-

tions, to make suggestions, to challenge everything he taught them. He was a

refreshing change to the dour seriousness of figures like Grosseteste or Aquinas,

and he clearly enjoyed his success.

Bacon’s chief goal in life was to do for the sciences what the scholastics were

trying to do for theology, to synthesize all knowledge into a harmonious system.

This meant nothing less than acquiring a full mastery of subject after subject, from

astronomy to zoology, and Bacon threw himself into the gargantuan task with

typical aplomb. But he did more than read the works of other scientists; he himself

was a passionate champion of experimentation—the setting up of experiments, the

gathering of data, and the work to deduce general laws from them.

Anyone who wishes to rejoice with certainty in the natural laws underlying

natural phenomena must first learn to dedicate himself to experimenting—

for so many authors write so many things (and so many people believe them!)

solely on the basis of logical deduction without the benefit of direct experi-

ence, and such reasoning is wholly false. For example, it is widely believed

that the only way to split a diamond is by daubing it with goat’s blood, and

[deductive] philosophers and theologians continue to spread this falsity. Yet

a bloody jewel-cutting of that sort has never been accomplished, though it’s

been tried ever so many times; but a diamond can be cut without blood [by

an ordinary gem-cutter] at any time....Letallthings [in science] be verified

by experience.

In this way, he developed the principles for creating the first rudimentary telescope

and the thermometer; he also determined the chemical composition of gunpowder.

He laid out, two hundred years before Leonardo da Vinci, schematic designs for

airplanes, automobiles, and motorized boats. It is important to bear in mind, how-

ever, that by the word experiment Bacon and his contemporaries meant something

closer to our use of the word observation. Real controlled experiments, in the mod-

ern sense, were still a thing of the future. Still, Bacon advanced the frontiers of

knowledge in dramatic ways. The more he learned, the greater the scorn he heaped

320 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

on others, especially theologians (whom he generally regarded as stupid and use-

less—and said so). The Franciscans grew worried, since they feared reprisals from

the theologians who winced under Bacon’s withering criticism. Moreover, at least

one of Bacon’s theories was troubling. Bacon loved science and believed it held

the key to understanding the cosmos. He maintained, in fact, although he never

used this terminology, that there was a single master code in control of the uni-

verse, a genuine physical analog to what priests in the pulpit constantly referred

to as “God’s plan.” A properly trained scientist like himself, Bacon insisted, but

not the “idiot jackasses” he saw all around him, could crack that code and un-

derstand the universe’s deepest secrets. He was convinced that such a discovery

was God’s intent for mankind—why else would He have given us the capacity to

reason?—but he also came to believe that scientific knowledge could prove to be

dangerous if it fell into the wrong hands; Bacon in fact ultimately concluded that

Antichrist himself, when he appeared, would be a scientist. It is through science,

evilly employed, that the work of Satan will be done. There was nothing intrin-

sically heretical in such an idea, but since it was the Franciscan order that was so

closely associated in people’s minds with scientific research, it did not seem wise

to Bacon’s superiors to let him continue his work. In 1257 he was ordered into an

abbey in Paris—essentially house-arrest—and his books were submitted for cen-

sorship by the Ministers General of the order.

Bacon appealed to Rome for help for several years without luck, but in 1265

the new pope Clement IV (1265–1268) took interest in Bacon’s plight and was

especially intrigued by Bacon’s project of writing a massive encyclopedia of all

science, a kind of summa scientifica. Clement told Bacon to start writing and to send

some sample excerpts to him. But Clement died in 1268, leaving Bacon stranded.

He came to recognize that even if he could find another papal champion, he would

never live long enough to complete his great work. He reconciled with his Fran-

ciscan superiors, returned to England, and spent his last two decades in quiet

study. He continued to write and to work in his laboratory, but his greatest ac-

complishments were behind him. He died in 1292.

The study and practice of science at the medieval zenith thus paralleled other

aspects of medieval cultural and intellectual life: It was approached, at least by its

new innovators and enthusiasts, as a comprehensive whole, a vast harmonious

system that could be understood by reason and confirmed by observable data. The

cosmos made sense, the scientists triumphantly declared, and God’s glory was

made manifest. The interconnectedness of all things, an ages-long intuitive belief

of human beings, had been proven to be the case by the thinkers of the thirteenth

century, and in that interconnectedness lay the ultimate balance, stability, and

beauty of Creation.

But there was a darker, less rational, yet still vaguely scientific aspect to Cre-

ation as well, an aspect best approached through magic. The term ars magica

(“magical art”), throughout the early and central Middle Ages, meant any sort of

spell, incantation, potion, use of amulets or stones, or any other type of sorcery

that invoked the power of demonic spirits—not necessarily Satanic spirits, as peo-

ple often think, but forces beyond the realm of the normal visible material world.

Early medieval magic had numerous cultural roots: Greco-Roman, Germanic, and

Celtic. It is very difficult to sort out which belief derived from which source. We

discussed some of these early beliefs when we examined folkloric practices that

remained in early medieval culture even after Christianization. Many such prac-

tices survived conversion since in common opinion they did not contradict Church

teachings in any obvious way. Thus we find early medical texts prescribing such

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 321

unlikely cures as spitting into the mouth of a frog as a means of relieving oneself

of toothache; the recommended treatment for gallstones was to smear the afflicted

person’s abdomen with the blood of a goat that had been slaughtered by a virgin

and gathered up in clean cloths by a troop of naked boys.

4

The idea behind such

practices was to invoke the assistance of another spirit/demon/life-force through

a ritual that was not in itself scientific but which could nevertheless resolve a

scientific (in this case a medical) problem.

By the thirteenth century, scholars’ attitudes toward ars magica had changed

significantly. Specifically, they now distinguished between two general varieties of

artes magicae. Scholars deplored base folk-beliefs that they regarded as demonic—

anything involving incantations or the summoning of spirits, for example—but

they upheld the scientific validity of what they called magica naturalis (“natural

magic”). Natural magic worked in slightly different ways from magical art, ac-

cording to different writers, but in a general sense it can be defined as the power

of the miraculous that is everywhere in God’s creation—and it is the role of science

to learn how to harness whatever aspects of the miraculous power God sees fit to

allow us to reason out. It is magica naturalis that splits light into a spectrum of

dazzling colors after passing through a prism, for example, but it is the science of

optics that figures out the precise mechanism of how to behold the miracle and

what to do with the knowledge attained by it. Magica naturalis, scholars believed,

was one of the forces that held together the great ordered cosmos, so studying it

was essential to the thirteenth-century dream of synthesizing all knowledge. Writ-

ers as sober as John of Salisbury and Thomas Aquinas believed in natural magic.

Pope Boniface VIII (1294–1303) eagerly submitted to being treated with amulets,

gemstones, and incense for his dyspepsia. The world was literally a magical place

to thirteenth-century scientists, and God’s glory was revealed in every minute bit

and working of it.

A

SPECTS OF

P

OPULAR

C

ULTURE

Not all creative medieval life took place in noble courts, university libraries, or

ecclesiastical settings; much of the most exciting and interesting cultural vitality

was centered in taverns and village greens, in workshops and rural fairs. Rural

and urban commoners possessed cultural lives of uncommon richness, if the sur-

viving evidence is representative. For most of the Middle Ages very little is known

of popular culture above the material level—the type of tools people used, the

clothing they wore, the buildings they lived in, etc.—but by the thirteenth century

we know a surprising amount about peasants’ and town-dwellers’ popular songs,

dances, folktales, festivals, games and sports, diets, occasionals fads, and unflag-

ging vices. The character of the age determined this, to an extent: “Study every-

thing,” Hugh of St. Victor wrote to an earnest young scholar who had asked him

for advice, “eventually in life you will come to understand that nothing is super-

fluous.” As the passion to know spread, and as literacy spread with it, people

began to write down more things than they had done in earlier times. A new

technology made this task easier and more affordable: papermaking. Paper mills

were part of the booty of the Spanish Reconquista, and as the knowledge of pa-

permaking spread through Europe in the thirteenth century, it allowed people the

4. These prescriptions appeared in a book called De medicamentis (“On Treatments”) by Marcellinus

Empiricus, who lived near Bordeaux around the year 400.

322 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

comfort of setting down in ink a record of the most mundane details of life: private

letters, diaries, grocery lists, sketches and doodlings, silly poems, or whatever. It

is often through such haphazard records as these that we reconstruct the popular

life of the commoners.

Festivals and holidays punctuated the commoners’ lives, so it is not surprising

that much of our knowledge of their popular pastimes is centered on them.

Whether people tilled the land or toiled in a shop, medieval life was one of hard

labor for most of them, but it was not unremitting gloom. Approximately one

hundred days out of each year were Church-proclaimed holidays during which

there was to be no work.

5

(An average of one day of rest for every three days of

labor is rather attractive by today’s standards.) Fasting usually preceded feasting—

in part as a spiritual exercise, in part as a way to increase the appetite—and prayer

services were usually followed with much singing, dancing, games, and drinking.

It is impossible to offer a comprehensive view of medieval popular culture since

it varied so much from locale to locale, but it may be worthwhile to point out

almost at random a few particular examples of how the people celebrated, rested,

and enjoyed themselves.

Popular music had its roots far back in various traditions, as we saw in an

earlier chapter with forms like the chansons de geste and the love lyric. By the

thirteenth century, we find even highly respected composers of Church music writ-

ing secular pieces; they had probably always done so in the past but had never

deigned to attach their names to their secular works. There were probably two

reasons why it suddenly became acceptable to “admit” to composing secular mu-

sic: The love that this music so frequently celebrated (courtly love) had been Chris-

tianized and made acceptable, and the music itself became much more sophisti-

cated. French composers like Philippe de Vitry and Guillaume de Machaut were

among the first to adapt the motet form, as developed by ecclesiastical composers

like Le´ontin and Pe´rontin at the Church of Notre Dame in Paris, to secular topics.

6

Genres were fluid, performances more so. Professional musicians like jongleurs or

minstrels proved their talent not only performing songs as written but by impro-

vising new lyrics and harmonies on the spot to please a particular audience. Clev-

erness and audacity were valued equally—along with the discernment to know

when to employ them—in poking amiable fun at a local character, offering gentle

bawdy humor, or criticizing current events. Performers were lionized and pilloried

with roughly equal frequency. The Franciscan chronicler Salimbene tells of his

admiration for one musically gifted friar:

Brother Henry of Pisa was a handsome fellow, medium height, always gen-

erous, courteous, charitable, and cheerful. He knew how to get along with

everyone...[and he could] compose the sweetest and most charming songs,

5. These would have been: the approximately fifty Sundays of each year, the twelve-day season from

Christmas to the Feast of the Epiphany, Holy Week (Easter), the major saints’ festivals (the Annunciation,

25 March; Sts. Peter and Paul, 29 June; All Saints, 1 November), the moveable feasts like Pentecost, Holy

Trinity, and Corpus Christi; plus whatever patron saints’ days were celebrated locally in each region,

town, or village. On manors it was also common to observe the birthdays, saints’ days, or wedding-

days of the lords’ family members as well.

6. The motet (which derives its name from the French word mot, meaning “word”) was perhaps the

most important musical form to emerge in the thirteenth century. It originated in the practice of adding

a sung text that rose above the melodic line of plainchant, thus introducing “two-part” harmony or

polyphony. Vitry and Machaut were the first to set secular vernacular texts to such form and quickly

expanded it to include more voices and melodic lines.

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 323

both in harmony and in plainsong, and he was a marvelous singer...Once,

hearing a certain young woman going through the cathedral at Pisa while

singing in the vernacular tongue

If you care no more for me,

I will care no more for thee.

he at once began to sing this hymn, using the exact same melody

Christ divine, Christ of mine,

Christ O King and Lord of all.

Yet Salimbene is also careful to report that numerous Church authorities have

warned of the dangers of all music, even ostensibly religious music:

no matter if it is instrumental or vocal....Remember that Orpheus, with his

lute, followed his desire straight to hell itself. Note too that one hardly ever

finds a man in this world with a light voice and a grave life....Ihave known

innumerable men and women, the heightened sinfulness of whose lives cor-

responded exactly to the increased sweetness of their voices.

Most professional musicians came from the lower or middle orders of society. The

most prominent exception to this rule were the German Minnesa¨nger. They were

troubadour poets in the courtly love tradition (Minne is Middle High German for

“courtly love”) who flourished from the late twelfth to the early fourteenth cen-

turies, especially in the Rhineland and in Bavaria; they were typically drawn from

the German aristocracy.

7

So long as it remained an aristocratic art form, the Min-

nesang retained its allegiance to traditional themes of a knight’s perfect love for

an unattainable lady and of loving service without earthly reward, but the rising

importance of the German towns and early bourgeoisie meant that the old forms

were given new life and thematic elements toward the start of the fourteenth

century. The greatest of the Minnesinger poet-composers was Walther von der Vo-

gelweide (d. 1230), who was a favorite of emperor Otto IV (1208–1215) and of

Frederick II.

Many hundreds, even thousands, of popular lyrics survive for which we do

not have any corresponding music. They were not necessarily sung, and were not

necessarily associated with any particular festival or occasion. Then as now people

wrote songs to commemorate the everyday events of life, like this example from

thirteenth-century England—about a young man’s infatuation with his first love,

a girl named Alison.

Bitweene Merch and Averil,

When spray biginneth to springe,

The litel fowl hath hire wil

On hire leod

䊳

to singe. In her language

Ich libbe

䊳

in love-longinge I live

For semlokest

䊳

of alle thinge. the loveliest

Heo

䊳

may me blisse bringe: She

Ich am in hire baundoun.

䊳

power

An hendy hap ich habbe yhent,

䊳

A lucky chance I have received

Ichoot

䊳

from hevene it is me sent: I know

From alle

䊳

wommen my love is lent,

䊳

all other / withdrawn

7. By the start of the Renaissance these figures had evolved into the Meistersingern (“Mastersingers”).

The Mastersingers were urban-based guild musicians, not court-based nobles.