Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

304

CHAPTER 14

8

A

RT AND

I

NTELLECT IN THE

T

HIRTEENTH

C

ENTURY

T

he intellectual and artistic production of the thirteenth and early fourteenth

centuries, arguably the high point of medieval cultural life, was the grand

culmination of the twelfth century’s hectic energies. In virtually every artistic me-

dium—architecture, painting and sculpture, poetry, drama, music, and dance—

Europe produced a nearly dizzying array of masterpieces, works that can still

astonish us with their creative power. From the cathedrals at Durham, Chartres,

Cologne, Venice, or Barcelona, through the poetry of Chre´tien de Troyes, Bernat

de Ventadorn, Wolfram von Eschenbach, Guido Cavalcanti, Dante Alighieri, and

the anonymous author of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, to the dream-visions of

Hildegard of Bingen, (the most original woman writer of the Middle Ages), the

anonymous authors of the great mystery and morality plays, the stories of Chris-

tine de Pizan and Giovanni Boccaccio, the bawdy adventures of the fabliaux, and

the polyphonic music of Le´onin and Pe´rotin, medieval Christendom at its height

was bursting with talent, dazzling audacity, and the confidence to accomplish

enduring art.

All this creative energy flowed into well-established genres and overflowed

into several new ones. In literature the dominant forms were those of traditional

epic and lyric poetry and drama, but also the new genres of verse romance and

prose fable. By the end of the thirteenth century, the Catalan lay evangelist Ramon

Lull had written Europe’s first novel—an unencouraging debut work called Blan-

querna. In ecclesiastical architecture the heavy sternness of the Romanesque style,

with its massive walls and columns, dark interiors and dank atmosphere, gave

way to the soaring elegance of the Gothic, which emphasized light, color, majesty,

and transcendence, while the sculpture and painting that adorned the churches

steered away from the (literally) fantastic playfulness of Romanesque allegory and

abstraction toward the idealized naturalism of Gothic style that paved the way for

the heightened realism of the Renaissance of the fifteenth century. Medieval music,

whether love-longing troubadour songs or liturgical motets, grew in complexity

and sophistication to include two- and three-part harmonies and a plethora of new

instruments.

Intellectual life showed the same vitality and ambition. In the areas of philos-

ophy and theology, thinkers brought to fruition the great rationalization of intel-

lectual thought and religious belief begun by the neo-Aristotelians of the twelfth

century. An entire intellectual movement begun in the cathedral schools and uni-

versities, and hence called scholasticism, confidently asserted its ability to provide

rational proofs and explanations for literally every tenet of Christian faith. The

greatest of the scholastics, St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), nearly lived up to the

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 305

boast. The scholastics may have been, in a sense, less original than the great think-

ers of the twelfth century, more summarizers and systematizers than bold creators,

but their achievement in synthesizing faith and reason and providing a compre-

hensive blueprint for the rational organization of the cosmos is enormously im-

pressive. They personify, in fact, the general medieval outlook we have been trac-

ing in this book—the belief in the fundamental cohesion and orderliness that lay

behind and gives meaning to the anarchic heterogeneity the world presents us

with. The modern world has largely rejected the scholastics’ synthesis, but their

achievement still deserves respect.

The greatest intellectual originality occurred in the sciences. By the start of the

fourteenth century, advances in fields like medicine, astronomy, optics, physics,

mathematics, and geometry, and in their applications, had opened up whole new

worlds of inquiry and had given Latin Europe a decided scientific and technolog-

ical advantage over the rest of the then-known world. Scientists like the English-

men Robert Grosseteste (1170–1253) and Roger Bacon (1214–1294)—the latter one

of the most colorful figures of the age—accelerated the rise of empirical and ex-

perimental science that, for both good and ill, has dominated much of modern

intellectual life in the west. “Whoever wishes to rejoice in the universal truths that

underlie the visible phenomena [of the world], and to do so without a hint of

uncertainty, must first learn to dedicate himself to experiment,” Bacon wrote. His

experimentation, his certainty, and his joy all characterize the intellectual and ar-

tistic life of the medieval world at its zenith.

S

CHOLASTICISM

Scholasticism is, like feudalism, one of the traits most closely associated with the

Middle Ages in our popular culture, and like feudalism its common repute is

vaguely but decidedly negative. The word itself conjures up images of dry-as-dust

encyclopedias of abstract theological minutiæ, and of arcane arguments carried to

absurd lengths. “How many angels can fit onto the head of a pin?” is a good

example of a stereotypical scholastic question. (This particular question was a sup-

posedly clever way of inquiring whether or not angels were corporeal beings.)

Simply and specifically, the word scholasticism refers to the philosophical and ped-

agogical method utilized by the faculty of the cathedral schools and universities.

It was indeed a method more than a universally accepted set of ideas. Scholastic

philosophers disagreed with one another in hundreds of ways, but they did agree

on a foundational principle: Whether one began, in Platonic mode, with over-

arching theories and worked one’s way down to empirical specifics, or if one

proceeded, in Aristotelian fashion, from raw empirical data and painstakingly col-

lated them into general and universal theories, one would in fact find that the

cosmos had a divinely ordained rational ordering. Everything that happens, scho-

lastics were convinced, happens for a reason, and every idea, fact, occurrence,

physical being, and social construct has a place in that ordering. God has given

us the ability to perceive and understand that cohesive unity, and man’s duty is

to arrange his life in such a way that it emulates and harmonizes with God’s

evident intention.

The scholastics argued, like their twelfth-century forebears, that faith and rea-

son were completely reconcilable. While none of them maintained that faith and

reason were the same thing, most would have asserted that faith had a profound

rational component and was thus a rational activity, a commitment to truths whose

306 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

truth could be demonstrated. This is quite a different position from that of the

Church Fathers in the earliest centuries of Christianity, the figures whose ideas

had dominated the first thousand years of Christian thinking. They had main-

tained that faith was by definition an irrational activity—a profession of belief that

could not be proven to be true. As the third-century writer Tertullian described it:

What does Athens have to do with Jerusalem? Where is the meeting ground

between the Academy and the Church?...Enough of these efforts to produce

a quasi-Christianity based on Stoic, Platonic, and dialectical ideas! We don’t

want an argument for believing in Jesus Christ, and we don’t need a logical

analysis in order to appreciate the Gospels!

He summed matters up in his most often-quoted line about Christianity: “I believe

it because it is absurd!” Attitudes had changed by the twelfth and thirteenth cen-

turies, however, not least because of the Church’s own attempt to codify, ration-

alize, and systematize its doctrine. The enormous elaboration of that doctrine by

the scholastics occurred in part merely as an expression of intellectual excitement,

the desire to play with ideas for their own sake and to take them as far as logical

thought could go, but it was also done out of evangelical zeal. If Christian con-

victions could be rationally proven to be true, the scholastics believed, then the

long-hoped-for conversion of the Jews and Muslims might at last be attained. What

could possibly hold them back from accepting a demonstrable truth? And since

these peoples had so long excelled at philosophy, what delight in beating them at

their own game! It is no coincidence that one of the greatest works of the scholastic

movement (by Thomas Aquinas) was entitled Summa contra gentiles, or “Summary

[of Arguments to be Used] against the Non-Christians.” The enormous cultural

confidence of medieval Europe at its zenith is nowhere clearer than in its convic-

tion that the universal victory of Christianity was at hand—or at least that the

tools to effect it were.

Although the scholastics, who came to be associated especially with the Uni-

versity of Paris but were to be found throughout Europe’s universities, never de-

vised a comprehensive syllabus or platform, they generally agreed on three basic

assumptions about the nature of Truth: that it was to be found through Argument,

that it was to be found through recognized Authority, and that it was Additive.

The first aspect, the argumentative, is the rationalistic element: the belief that by

posing questions and proposing logical answers to them, and then subjecting the

answers themselves to further questioning, one gradually arrives at truth. This

technique explains the unappealing formalistic appearance of most scholastic texts.

They proceed not as long discourses of seamless prose but as bare-bones outlines

of numbered questions and answers; they have the aesthetic charm of computer

instruction manuals.

1

But in a sense this comparison heightens their utility: One

can proceed directly to the most specific question one has and confront it as an

independent whole, without relying upon what has gone before or comes after.

The second order of Truth is that derived from authority. Chief among the rec-

ognized authorities, of course, was the Bible in Jerome’s Vulgate version, followed

by the writings of the Latin and Greek Fathers, especially the Four Latin Doctors.

But appeal to authority, even to the Bible itself, never sufficed to prove a point for

the scholastics, who regarded such measures at best as corroborating evidence for

an argument from Reason. Despite their divinely inspired nature, all authoritative

texts were, after all, human productions and therefore fallible. Peter Abelard’s Sic

1. But then, some might argue that that is their closest modern analog!

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 307

et Non had amply shown that fact, although none of the scholastics was very keen

about mentioning his name again. Finally, the scholastics regarded all truth as

additive—that is, all truths in all areas of human experience and knowledge are

harmonious and reconcilable. There exists an essential unity of truth, and any ap-

parent contradictions or inconsistencies in human knowledge are the result of

imperfections in our understanding, not of flaws in nature.

Not everyone was enthusiastic about the scholastic program. St. Bernard of

Clairvaux, as we have seen, implacably opposed what he regarded as a devilish

attempt to subordinate faith to mere human reason. Scholars coming out of the

Franciscan order especially tended to favor the more traditional Platonic-

Augustinian approach to philosophical matters. Revelation took precedence over

reason, they maintained. God is rational but He is also more than that, and unques-

tioning acceptance of the scholastic method reduced God’s majesty and mystery.

A good example of this countermovement was St. Bonaventura (1221–1274), who

studied philosophy and theology at the University of Paris and was a close friend

of Aquinas in their university days. Bonaventura rose to be the Governor General

of the Franciscan Order and was a leading member of the College of Cardinals.

To him, one’s capacity for love and goodwill had more significance than one’s

rational faculties for achieving union with God: “If you ask how [divine things]

may be known, my answer is: turn to grace instead of doctrine, desire instead of

knowledge, the groaning of prayer instead of the labor of study—in a word, to

God instead of man.” But man’s intellect is not without value. Bonaventura in-

sisted that reason is an unparalleled tool for investigating and understanding the

physical cosmos and should be cultivated; but we ought not to let our enthusiasm

lead us into thinking that we can think-out God. In one of his most important

books, The Mind’s Road to God, he elaborated his view about the glorious power,

but also the limitations, of human reason. Our intellectual capacity carries us far

down that road, he argued, but the last stage of the journey depends solely on

our capacity for nonrationalized love.

The scholastic movement is most closely associated with Dominicans like Al-

bertus Magnus (d. 1280) and his most brilliant student Aquinas. Thomas Aquinas

(d. 1274) was the son of a Norman-Italian aristocratic family that expected him to

enter the Benedictine order and take his rightful honored place in society as an

abbot. He surprised them, though, by choosing to be a Dominican priest, vowing

himself to poverty and the life of the mind. His personality was that of an absent-

minded academic; in many ways he resembled the great German metaphysician

of the nineteenth century, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who was renowned for

being in such a cogitational fog that he once walked into a lecture hall in his

stocking feet, not having noticed that his shoes had come off in the mud outside

the building. Aquinas reportedly was once so lost in thought on a philosophical

point that he never felt the cutting and poking of a surgeon operating on his

infected ear.

Odd though Aquinas may have been as a personality, his teaching and think-

ing were brilliant. He began his career at the University of Naples and later taught,

in two separate stints, at the University in Paris. Between teaching jobs he served

as an advisor to the Holy See, specifically regarding the effort to reunite the Latin

and Greek Churches. Students flocked to his lectures and he quickly earned a

reputation not only for vast knowledge and subtle argument but for an ability to

get the students enthusiastic about what he called the “wonderfulness” of every

topic. He also had an exceptionally busy pen: His writings fill thirty volumes. (He

wrote so fast, in fact, that he developed his own personal shorthand system so

308 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

that his secretaries could keep pace with him.) The two works that have estab-

lished his reputation as the greatest of the scholastics are the Summa contra Gentiles

that we mentioned before and the Summa theologica (“Theological Summary”). The

first aimed to provide rock-solid logical arguments both for Christian beliefs and

against the prevailing notions of the non-Christian faiths—be they Judaism, Islam,

paganism, or one of the Christian heresies then so common. Since the Summa contra

Gentiles was meant to be a sort of handbook that evangelists could carry with

them and consult whenever they disputed matters with non-Christians, it is a

shorter and rather elementary work—a kind of evangelical crib-sheet. But it makes

fascinating reading, not least for the way it illustrates the extent to which Christian

scholars truly understood the subtleties of the other faiths. The Summa theologica,

by contrast, is an immense work of synthesis. Aquinas’ aim was literally to prove

every tenet of Catholic Christianity without recourse to Biblical authority, papal

decree, conciliar pronouncement, or appeals to trust in faith. His method could

hardly have been more thorough. He begins with a question—“Does God exist?”—

and offers an array of every possible logical argument that might prove the exis-

tence of a deity. He then offers every logical argument against his initial proposi-

tions. He then reverses course once more and details all the arguments against the

rebuttals; and so on, back and forth constantly until he has utterly exhausted every

conceivable pro and con argument. Then, having reached the conclusion that God

does indeed exist, he moves on to the next question and repeats the entire process.

The Summa theologica is not an easy book to read. It is of enormous length,

mind-numbing detail, highly technical language, and has virtually no stylistic el-

egance. Aquinas exerts no effort at all to make the reading experience a pleasant

one. To pick just one example, here is how he starts his discussion of the question

“Does human law bind a man’s conscience, or merely his actions?” [That is, does

obeying a law require us to accept that law as right in the solitude of our own

minds, or merely to obey it mindlessly in terms of our actions?]

Laws are deemed to be just by their end-result (namely, when they result in

the common good), by their author (that is, when a given law is promulgated

within the jurisdiction of the lawgiver), and from their form (that is, when the

law places an equitable burden on its subjects in proportion with their position

in society and is done so for the common good). For since every individual

is a part of a community, so does each man, all that he is and all that he

possesses, belong to the community as well—since anything that is an intrinsic

part of something else belongs to that something else. So too does nature

inflict a burden on the individual part in order to save the whole—and for

this reason human laws that impose proportionate burdens are just and bind-

ing in conscience and are therefore legal laws.

That is as plainspoken (and as riveting, in terms of narrative flow) as the Summa

theologica ever gets.

But scholastic works like these are tremendously important as cultural phe-

nomena. The mere conceit that a rational explanation can be given for everything

taught by the Church is a stunning example of intellectual pride and cultural

confidence. Few people would even suggest the possibility of such a thing today.

But in the thirteenth century, medieval Christendom was bursting with just that

sort of certainty. The Church had been reformed, society brought under the papal

monarchy, the Latin and Greek Churches brought within reach of reunification,

and intellectual life revitalized; universities were proliferating, economic prosper-

ity was abundant, governments were professionalized, centralized, and kept in

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 309

check by representative institutions. Who could doubt that the Christian world

had finally achieved its perfect, natural, and divinely ordained structuring in a

perfect, natural, and divinely ordered cosmos?

Aquinas experienced a mystical vision in 1272 in which he perceived that the

divinely-ordained truth whose perfect ordering he was so busily proving in his

Summa was actually something quite different, larger, stranger, and inexplicable.

He emerged from this revelation with the conviction that “everything I have writ-

ten seems to me to be mere straw.” He never completed the book, and seems to

have given up writing theology and philosophy altogether. He gave himself over

to pious simplicity and died soon after, spending his last months seeking “to be

serene with frivolity, and mature without self-importance.”

Aquinas was canonized in 1323 and given the title of Angelic Doctor. But even

in his last years, there was a considerable backlash in intellectual circles against

his brand of unshakeable rationalism. Most of the Franciscans and secular clergy—

those churchmen most at work in the regular world, instead of ivory-tower aca-

demics like Aquinas—were opposed to what they regarded as the heartless the-

orizing of the scholastics. Nevertheless, Aquinas’s extraordinary achievement sur-

vived the challenge, and the Summa theologica is second only to St. Augustine’s

City of God as the most important philosophical and theological work of the Middle

Ages.

T

HE

G

OTHIC

V

ISION

The exuberant confidence of the scholastic writers was shared and expressed by

the artists of the age, who enjoyed a period of extraordinary creativity. The sheer

ubiquity of artistic opportunities accounted for much of this creativity. Towns,

castles, cathedrals, smaller churches, urban mansions, and universities were

sprouting up everywhere, giving artists of every variety the opportunity to de-

velop and perfect their techniques. Major new developments occurred in lay and

ecclesiastical architecture, decorative tapestry, painting, and sculpture; the courts

of urban magnates and rural lords provided venues for vernacular literature and

popular song. Cathedrals rang with new sacred music in polyphonic style. Court

fashions favored sumptuous designs in dress and needlework. Poets sang lyrics,

players performed theatricals, musicians played in courts and fairs and on village

greens. Europe practically hummed with creative energy.

It is hardly surprising that the great churches and aristocratic courts were the

sites where most of these energies were at work. As the leaders of reformed Eu-

rope, they were naturally the principal patrons of art; nor is it surprising that much

of the art they commissioned aimed at glorifying their centrality to medieval life.

A common theme of medieval art was the cohesion and unity of society under

the leadership of the great powers. “Christendom,” the ideal vision since Charle-

magne’s time, had become a meaningful cultural and religious reality (or at least

medieval leaders liked to think so) and was deserving of praise and celebration.

As theology was “Queen of the Sciences” (in Albertus Magnus’s phrase), ar-

chitecture, and specifically religious architecture, was the dominant art form. From

one end of Europe to another, tens of thousands of cathedrals, churches, abbeys,

and monastic chapels were constructed in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In

France alone, workers mined more stone for building churches in these two hun-

dred years than the slaves of ancient Egypt quarried in three thousand years

of pyramid-, temple-, and palace-building for the pharaohs. In Mediterranean

Europe, workers turned first to the already-quarried stone of the old Roman ruins,

310 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

which they simply dismantled. The Colosseum in Rome, for example, which in

the eleventh century had been used as an enclosed meadow for pasturing sheep,

lost much of its stone for use elsewhere. Quarrymen, stone masons, architects,

engineers, and construction workers of all types had little difficulty in finding

employment. Even today literally thousands of churches from this era survive, in

whole or part, across Europe.

As anyone knows who has visited them, Europe’s cathedrals were immense.

This was construction not on the large but on the colossal scale. Nothing like these

buildings had been attempted in a thousand years; even the enormous monastic

abbey at Cluny owed its size to accretion rather than original design. The largest

church in pre-reform Europe had been Charlemagne’s imperial church at Aachen;

modeled on the Byzantine basilica at Ravenna, its central sanctuary—an octagonal

shape—measured a mere fifty feet in diameter, roughly the size of a typical lecture

hall in a modern university. The interior of London’s great Westminster Abbey, by

contrast, which William Rufus had built in two years (1187–1189), measured two

hundred and forty feet by eighty feet—ten times the square footage of the Aachen

sanctuary. Twelfth- and thirteenth-century churches were also very tall, as archi-

tects and engineers mastered the technological challenge of supporting the weight

of such structures. The Gothic cathedral at Beauvais—a stunningly beautiful build-

ing—is tall enough that it could hold a fifteen-storey modern office tower inside

its central nave.

Two styles predominated: the Romanesque in the eleventh and early twelfth

centuries and the Gothic from the middle of the twelfth to the early fourteenth.

The Romanesque took its name from its use of rounded stone archways, such as

the ancient Romans had used. But Romanesque buildings looked only superficially

like Roman ones; they shared a building technique rather than an aesthetic style.

The Gothic style, by contrast, does not refer in any direct way to the early Goths.

The word itself was coined in the early modern period, which spurned all things

medieval, and was meant to imply crudeness of style. Fortunately, the word no

longer has that meaning for us. Gothic architecture’s most distinctive characteristic

is the pointed arch. In the Middle Ages the style we call Gothic was known as the

French Style since French artists were the first to employ it. But Gothic churches

were built everywhere from Portugal to Hungary and from Sicily to Sweden.

Early medieval churches had been primarily of a type known as a basilica,

usually rectangular in basic shape with a flat or only slightly sloping wooden roof.

Its floor plan was dominated by a central nave divided into aisles by rows of stone

columns. When one stood in the nave and looked toward the main altar one was

invariably facing eastward—that is, toward Jerusalem. At the eastern end of the

basilica, a transept intersected the nave at a right angle to give the overall floor

plan the rough shape of a cross. The altar stood at the intersection of the nave and

transept. A small rounded apse then extended beyond the altar, forming, as it were,

a curved head to the cruciform floor plan.

Romanesque churches developed out of the basilican style; they retained both

the eastward orientation and the cruciform shape, which in fact they made more

pronounced by increasing the size of the transept and apse in relation to the nave.

Romanesque architects also increased the size of the choir, which was located just

east of the transept but before the apse, and gave a new rectangular shape to the

apse in order to put it in greater harmony with the rest of the building. Their most

important innovation, though, was the roof. Basilican roofs had been strictly func-

tional: They were flat, wooden, and undecorated. (They were also a constant fire

hazard.) Romanesque engineers found a way to replace these roofs with rounded

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 311

Basilica de la Madeleine, Vezelay. There were many local variations

on the Romanesque and Gothic styles of architecture. In this example,

the abbey of La Madeliene in Vezelay (1104), the barrel-

vault of the nave was replaced by a new style that utilized a

groined-vault and transverse arches. The redistribution of weight

and stress that this involved made possible the introduction of more

windows, thus creating a more open and airy effect. (Scala/Art

Resource, NY)

stone vaults called barrel vaults that extended down each aisle of the nave. The

transept formed another barrel vault, and the intersection of the transept vault

and aisle vaults formed a new structure called a cross vault that was, in an engi-

neering sense, the structural key to the entire church. Cross vaults were of great

weight and generated enormous forces of downward and lateral thrust. In order

to support this weight and thrust, the exterior walls of Romanesque churches had

to be massive. Few windows were possible, since a window represents a weak

point in any wall, and early Romanesque churches could therefore be grimly dark.

But the oppressiveness of the atmosphere was lightened by the introduction of

312 THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

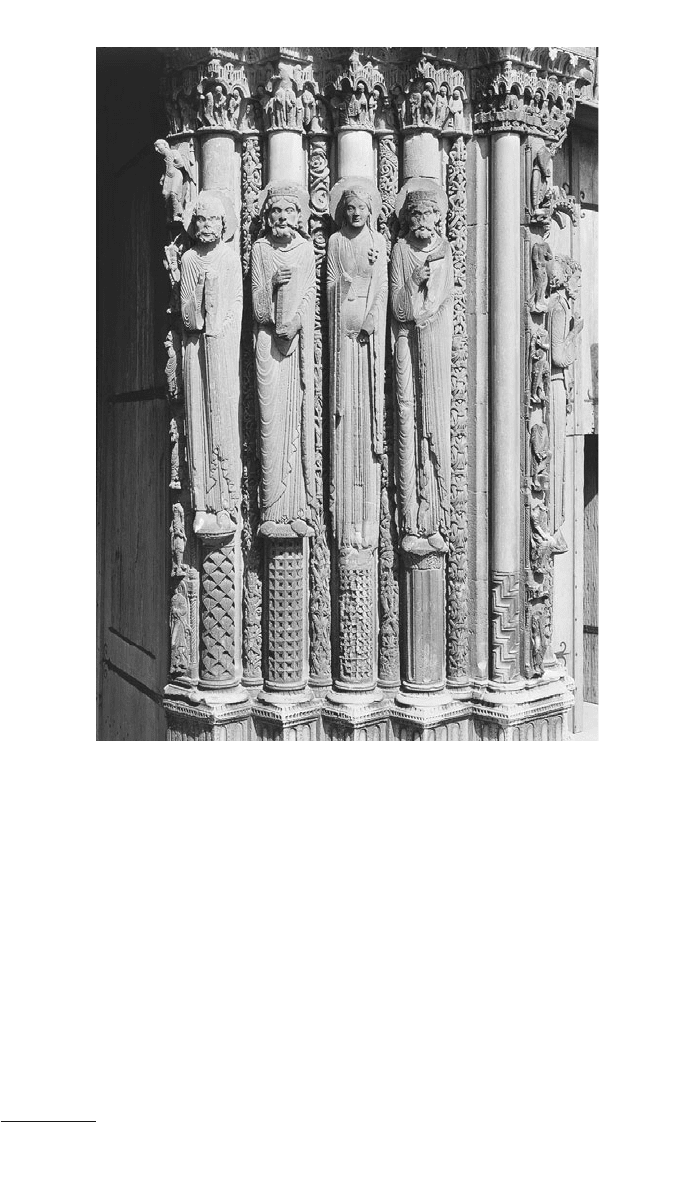

Statues from the “Royal Portal,” Chartres Cathedral. Ca. 1145.

These elongated yet still somewhat naturalistic portrayals of

four kings and queens of Judah are representative of

Romanesque sculpture at its best. Their formal poses and

idealized features are complemented by a faintly naturalistic

element in the drapery of their robes. (Giraudon/Art

Resource, NY)

ceiling painting, wall paintings, sculptured capitals,

2

hung tapestries,

3

gold and

silver ornaments, and the incense and music of the Mass.

These churches were also innovative on their exteriors. Unlike their usually

bare basilican ancestors, Romanesque churches had elaborate sculptures surround-

ing portals and extending along their exterior walls. The sculptures normally

formed a carefully planned program of images. The main western portal, for in-

stance, might have had a network of images designed to emphasize the theme of

2. Capitals are the decorative connection points where an arch meets the columns that support it.

3. Tapestries on the walls also helped to keep out some of the cold air radiating through the stone

walls.

ART AND INTELLECT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 313

God’s majesty, while a different portal—for example, the northern, which was

traditionally used by pilgrims rather than local parish residents—might carry im-

ages emphasizing the theme of penance. Symbolism and occasional abstraction,

rather than strict realism, frequently predominated here. Human figures were of-

ten presented in full human size in columnal sculptures, for example, but in un-

naturally elongated form. Romanesque portraiture was seldom naturalistic or true-

to-life. The main point of presenting, for example, an image of the biblical King

David was to emphasize his abstract, and therefore universally significant, kingly

quality rather than his specifically individual David-ness. Thus a Romanesque

sculptor might aim for an image that expressed authority, sternness, or the status

of lawgiver; this image was more important than a supposedly “realistic” portrait

of the actual man. Another new feature of Romanesque exteriors was the use of

towers. These often soared above the main body of the church, helped increase

the sounding power of the bells they contained, and gave the exterior of the build-

ing a new uplifted character.

The transition from Romanesque style to Gothic in the middle of the twelfth

century resulted from a host of factors. On an engineering level, new ways were

developed to increase both the height of the church and the number and size of

the windows that ran the length of the nave. These innovations both encouraged

and responded to the heightened emotionalism of popular piety as expressed not

only by pilgrims but by the townsfolk whose labor made the new churches pos-

sible in the first place. After all, building a cathedral required the backbreaking

work and financial support of thousands of people over periods of years, some-

times several generations. A Gothic cathedral was not merely a construction proj-

ect, it was an act of mass faith that required no less a commitment of devotion

than of money. One witness to the popular support for the construction of the

great Gothic cathedral at Chartres in the 1140s, marveling at the sight of hundreds

of townsfolk happily trudging off to the quarry, cutting stone, and hauling it back

over great distances, described the scene this way:

When these faithful people...setoutontheir path amid the blowing of trum-

pets and the waving of banners, it is a marvel to relate that their work went

so easily that nothing at all could discourage them or slow them down, neither

steep mountains nor rushing waters....It came as no surprise that mature

adults and the elderly took on this labor to atone for their sins—but what

inspired even adolescents and young boys to pitch in? Who brought these

children to that supreme Guide?...Thevast project begun by the adults will

be left for the youth to complete; and complete it they will, for they were

there to be seen, organized into teams with their own little leaders, tying

themselves with ropes to stone-laden wagons and pulling them as though

they weighed nothing, with backs erect (unlike the hunched and bowed shoul-

ders of the elders) and moving with astonishing speed and agility....When

they arrived back at the church site, they circled their wagons around it like

a spiritual encampment, and all through the night that followed this army of

the Lord kept watch with psalms and hymns. Candles and torches were lit at

every wagon; the sick and hurt were led away and had the relics of the local

saints brought to them for their healing.

The cathedrals became symbols of civic pride; their grandeur reflected the pros-

perity, piety, and public spirit of the people—so much so that neighboring towns

frequently competed with one another to see who could build the more impressive

edifice. The magnificence and centrality of cathedrals were also intended to reflect

the importance of the bishops who formed the backbone of the Church. More-

over, the unifying and systematizing passion of the age found expression in the