Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

466 Freedom Riders

Freedom Riders were all local activists: Jerome Byrd, James Burnham, and

Joe Lewis—three of the expelled Burgland students who had enrolled at

Campbell Junior College in Jackson. Arriving on Saturday morning “with no

advance notice,” they managed to enter the white waiting room and remain

there for several minutes. With the police almost outnumbering the small

number of whites at the scene, the three Riders exited the station to report

their success to CORE field secretary Tom Gaither and his assistant, Tougaloo

student MacArthur Cotton, who were sitting nearby in a car after driving

down from Jackson. Following a brief conversation, Cotton left the car and

walked over to a ticket window, where he tried to buy a ticket to Jackson. At

this point a group of whites who had been playing pool at a billiard parlor

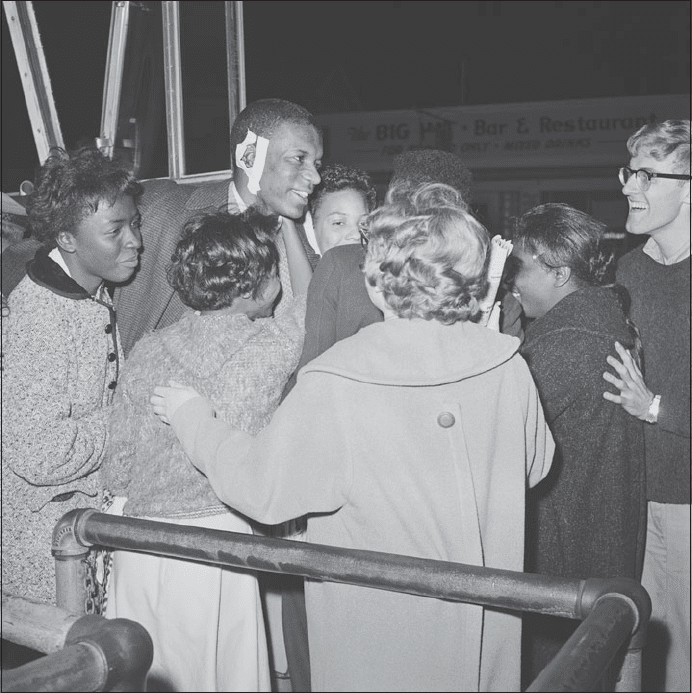

Freedom Rider Jerome Smith (with bandaged ear) arrives in New Orleans after

being assaulted by white protesters at the McComb Greyhound bus station on

November 29, 1961. The well-wishers surrounding him in the doorway are (left

to right) Patricia Smith, Jean Thompson, Doris Castle, Carlene Smith (dark coat),

and Frank Nelson. (Bettmann-CORBIS)

Oh, Freedom 467

across the street noticed what was happening and rushed over to the station.

Moments later a white man punched Cotton twice in the jaw, and several

others began beating and kicking the windows of the car. The police pulled

the attackers away before the car or its occupants suffered any serious harm,

and there were no arrests, but the incident deepened the sense of crisis. After

consulting with Farmer, Gaither reluctantly agreed to grant the city a “breath-

ing spell” before any additional Rides were undertaken.

41

To Judge Sidney Mize, the situation in McComb called for more than a

brief moratorium. On Saturday afternoon, just hours after Cotton’s narrow

escape, he issued a temporary ten-day restraining order prohibiting any ad-

ditional Freedom Rides in the city. Acting upon a joint request from panicky

city officials and the bus station operator, he set a hearing date for December

7 to determine if the temporary order should be extended or made perma-

nent. Even though CORE officials pointed out that Judge Frank Johnson

had already overruled a similar order in Alabama, Mize insisted that it would

be irresponsible to allow any further provocations to threaten civil order in

McComb. Outside interference, in his view, had disrupted the peaceful

course of local life, a judgment seemingly confirmed on Sunday morning

when John Oliver Emmerich Sr., the sixty-one-year-old editor of the

McComb Enterprise-Journal, was attacked on his way to church. A self-styled

moderate who had encouraged Mayor Douglas to comply with the ICC or-

der, Emmerich angered many local white supremacists when he allowed vis-

iting newsmen to use his office as their unofficial headquarters. Confronted

on the street by Melton Stayton, a forty-three-year-old oil worker who claimed

that the editor was “responsible for these out-of-town newspaper men being

here,” the physically frail World War I veteran was knocked to the ground

with a gash in his head. After several bystanders interceded, saving him from

further injury, Emmerich was more perplexed than angry. “The problem is

historic,” he later explained to reporters “The cause of it is not in this gen-

eration. That’s why I take a tolerant view of it. All of the people on the scene

are like pawns moved by destiny.” Others, including a local judge who sen-

tenced Stayton to thirty days in jail, were less philosophical. But, for many,

the incident underscored the volatility of race and class relations in one of

the Deep South’s most conservative communities.

At the December 7 hearing Judge Mize, as expected, extended the Free-

dom Rider restraining order for two weeks. Although CORE attorneys im-

mediately filed an appeal, there was little hope of overturning Mize’s ruling,

at least in the short run. To the dismay of CORE and the Justice Depart-

ment, the federal district judge assigned to rule on the appeal was Harold

Cox, the arch-segregationist who had recently foiled the attempt to protect

John Hardy’s right to register black voters in southwestern Mississippi. On

December 22 Cox upheld Mize’s ruling by granting an open-ended tempo-

rary injunction enjoining CORE from sponsoring any further Freedom Rides

to McComb. Stretching the limits of what one historian later called “blatant

468 Freedom Riders

sophistry,” Cox argued that the injunction was justified because it applied

only to outside agitators and not to blacks as a general racial grouping. There

was, he contended, no conflict with the ICC desegregation order. At the

urging of Burke Marshall, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals would eventu-

ally nullify the injunction, after summarily rejecting the conservative jurist’s

logic. But, for the time being, the McComb Freedom Rides, along with the

broader movement that Bob Moses and others had brought to the area, were

over. For movement leaders, as for the Justice Department, the irony of the

situation was inescapable. Of the seven communities placed under court or-

der by the Justice Department in 1961, McComb probably did the most to

tip the balance in favor of decisive federal action. Yet at the end of the year,

it was the only community where Freedom Rides were barred by law.

42

The developing situation in Albany was no less ironic. Here the Free-

dom Rides helped to inspire a local civil rights struggle that provided the

national movement with organizational opportunities and strategic dilem-

mas in almost equal measure. Before the year was over, the Albany Move-

ment, as the local struggle came to be known, would enlist thousands of black

citizens in a community-wide effort to hasten the demise of Jim Crow in one

of the nation’s most segregated cities. But it would also draw SNCC, SCLC,

and to a lesser extent the NAACP into a factional quagmire that would teach

Martin Luther King and other movement leaders a painful lesson about the

difficulties of mass protest in the Deep South. With Sherrod and Reagon

lighting the fuse, Albany became one of the first communities to feel the

explosive force, both positive and negative, of sustained mass participation in

nonviolent struggle. The sequence of events fueling this explosion began on

November 17, when representatives of several black community groups de-

cided to form an umbrella organization known as the Albany Movement.

Announcing a broad civil rights program calling for fair employment, an

equitable legal justice system, and desegregation of all public accommoda-

tions, including transit facilities, the Albany Movement soon entered into

preliminary negotiations with city leaders. At the same time, however, the

organization began planning mass demonstrations designed to push those

same leaders towards acceptance of movement demands.

As encouraging as it was, this adult activity could not keep pace with the

youthful rebellion fostered by Sherrod and Reagon. On November 22, the

day before Thanksgiving, three of Albany’s most impatient black activists—

all members of the NAACP Youth Council—attempted to desegregate the

white waiting room at the downtown Trailways station. Promptly arrested

by Chief Pritchett for breaching the peace, they spent less than an hour at

the city jail before being bailed out. But later in the day two Albany State

College students, Bertha Gober and Blanton Hall, made their own attempt

to violate the waiting room color line. Following their arrest, however, there

was no immediate release on bail. Over the next three days, as the two stu-

dents spent the Thanksgiving holiday in jail far away from their families,

Oh, Freedom 469

their plight attracted considerable attention in the local black community, es-

pecially among the leaders of the Albany Movement. On Saturday night, when

the movement convened a mass meeting at the Mount Zion Baptist Church to

protest the arrests, all five of the students were on hand to bear witness to the

spirit that had moved them. Both before and after the testimony, Reagon and

two talented young singers, Rutha Harris and Bernice Johnson, led the faithful

through stanza after stanza of a capella freedom songs, inaugurating the “Al-

bany Singers” tradition that would become the hallmark of the local civil rights

struggle. By the end of the evening the emotional surge in the Mount Zion

sanctuary had surpassed Reagon and Sherrod’s wildest expectations, spiritual-

izing the Albany Movement before their very eyes.

This new spirit was very much in evidence two days later when more

than five hundred demonstrators appeared outside the county courthouse

during the students’ trial. With a nervous Chief Pritchett monitoring their

every move, the demonstrators joined Charles Jones, recently dispatched from

the SNCC office in Atlanta, on a “prayer pilgrimage” from the courthouse to

Shiloh Baptist Church. Although Jones and his followers escaped arrest, city

leaders, including the conservative black administrators at Albany State,

warned the Albany Movement that it was courting danger. When Sherrod

tried to speak to a group of students on the Albany State campus the next

day, he was promptly arrested on a trespassing warrant. Over the next two

weeks there were no further arrests, but the pressure and excitement contin-

ued to build in the black community.

By early December Sherrod and his SNCC colleagues were pleased with

the local movement’s gathering momentum but concerned that the city re-

mained rigidly segregated with no real breakthrough on the horizon. Feeling

that both local communities, black and white, needed a little push, they asked

Jim Forman to organize a high-profile Freedom Ride from Atlanta to Al-

bany. On Sunday, December 10, Forman himself, along with seven other

Riders and one designated observer—Bernard Lee, Lenora Taitt, Norma

Collins, Bob Zellner, Joan Browning, Per Laursen, Tom Hayden, and his

wife, Casey Hayden (the observer)—traveled to Albany by train. Beginning in

mid-October—when Robert Kennedy had personally negotiated the desegre-

gation of trains and depots operated by three large railways systems, the South-

ern, the Louisville and Nashville, and the Illinois Central—most of the nation’s

railways, including the Central of Georgia line that served Albany, had re-

cently agreed to desegregate their facilities. So, as expected, Forman and the

other Riders encountered little trouble en route to Albany, even though they

made a point of sitting together as an interracial group. At one point an indig-

nant conductor tried to separate the black and white Riders, but the real trouble

did not begin until they entered the Albany railway terminal.

Arriving in the early afternoon, they were met by a grim-faced Chief

Pritchett backed up by a squad of police. Earlier in the day Pritchett had

sealed off the white waiting room, and by his order the Albany Movement

470 Freedom Riders

welcoming party inside the station was limited to Charles Jones, Bertha Gober,

and A. C. Searles, a local black journalist. Out on the street, however, a large

crowd of movement enthusiasts was waiting for the Riders to emerge. After

hustling the Riders through the waiting room, Pritchett became unnerved as

the crowd surged forward to greet them. When an order to clear the side-

walk went unheeded, he placed all eight Riders and three members of the

crowd, including Jones, under arrest.

With this impulsive act, Pritchett produced eleven martyrs and a black

community seething with outrage. Following an emotional mass meeting

on Sunday evening, the Albany Movement went into action as never before.

On Monday several movement supporters were arrested during a prayer vigil

on the city hall steps; and on Tuesday, the day the eleven defendants went on

trial, Sherrod led more than four hundred marchers through the heart of down-

town Albany. Undeterred by a steady rain and the taunts of disapproving white

onlookers, the singing and shouting marchers circled the city hall block twice

before Pritchett had seen enough. Herding the marchers into a nearby alley,

Pritchett ordered his officers to arrest the entire group for unlawful assembly.

By early afternoon 267 protesters were in custody. Although nearly half of

those arrested soon posted bond, 150 others, including Sherrod, remained in

jail overnight, in many cases for several days. Most, like Sherrod, ended up at

prison farms in nearby towns and counties that had agreed to accept the over-

flow from Albany’s small city jail. By Wednesday morning the Albany arrests

were front-page news all across the nation, and even Pritchett began to have

second thoughts about the wisdom of calling national attention to the city’s

troubles. Nevertheless, he found himself arresting 202 more protesters later in

the day. Many of those arrested were high school students that Pritchett soon

released to the custody of parents, but the youthful innocence of the demon-

strators did not weaken his resolve to maintain control of the situation. As he

explained to reporters: “We can’t tolerate the NAACP or the Student Non-

violent Coordinating Committee or any other ‘nigger’ organization to take

over this town with mass demonstrations.”

Sherrod and the local leaders of the Albany Movement were no less de-

termined to carry on the fight. In addition to demanding the release of all

prisoners and good-faith negotiation with city leaders on all matters related

to desegregation, they called for a boycott of twelve downtown stores oper-

ated by white segregationists. On Wednesday evening city officials quietly

agreed to indirect negotiations filtered through six mediators, three of whom

were black; and on Thursday Marion Page, the secretary of the Albany Move-

ment, announced that “some progress has been made,” primarily on the is-

sue of desegregated transit facilities. For at least some of Albany’s white

leaders, maintaining the color line at the city’s bus and rail terminals ap-

peared to be less important than restoring order. But there was more confu-

sion than clarity, both inside and outside of the negotiating room.

Oh, Freedom 471

Earlier in the day, Norma Anderson—the wife of Dr. William G. Ander-

son, the president of the Albany Movement—had led twenty demonstrators,

mostly high school students, to the white waiting room at the Trailways ter-

minal. After purchasing tickets to Tallahassee, Mrs. Anderson and nine oth-

ers sat down at a previously whites-only lunch counter and ordered coffee,

which, to their surprise, was promptly served by a black waitress. Ten min-

utes later, however, Chief Pritchett ordered their arrest. Carted off to jail,

they expected to be behind bars before noon. But to their amazement, a po-

lice spokesman soon informed them that the charges had been dropped. They

were free to return to the bus station, by police escort if they wished. Re-

lieved but not quite sure what to make of this reversal, Anderson led her

charges back to the station waiting room, where they remained for nearly an

hour, the first Albany blacks to experience at least partial compliance with

the ICC order.

43

Though somewhat encouraging, the developing situation at the Trailways

lunch counter did little to cool the fires of racial discord in Albany. While

Norma Anderson and the students were still at the terminal, Governor Ernest

Vandiver fulfilled Albany mayor Asa Kelley’s request to put 150 National

Guardsmen on alert at the local armory. And later in the day the negotiations

were temporarily suspended when Albany Movement leaders received a

After facing charges for disorderly conduct, SNCC executive director Jim Forman

and other Freedom Riders (from left to right, Bertha Gober, Bernard Lee, Forman,

Lenora Taitt, Charles Jones, unidentified, Norma Collins) leave the Albany, Geor-

gia, city hall while supporters kneel in prayer along the sidewalk, December 13,

1961. (Bettmann-CORBIS)

472 Freedom Riders

report that Sherrod had been “brutally beaten” by guards at a Terrell County

prison farm. Tempers cooled and the negotiations resumed only after Pritchett

allowed an obviously healthy Sherrod to appear at a mass meeting that evening.

“They slapped me a couple of times” and “cut my lip,” Sherrod told the

crowd, but there had been no beating. Relieved, the audience filled the hall

with amens and shouts of praise. Before the night was over, however, the

Albany crisis would take a strange and unexpected turn.

Reviving an idea floated earlier in the week, Dr. Anderson invited Martin

Luther King to speak to an Albany Movement mass meeting on Friday

evening, December 15. Although apologizing for the short notice, Anderson

insisted that the Albany crisis had reached a critical stage and King’s pres-

ence was needed to push the negotiations to a successful conclusion. Un-

aware that Jim Forman, Marion Page, and others were opposed to SCLC

involvement in Albany, King accepted the invitation, in part because Ralph

Abernathy, a college classmate of Anderson’s, urged him to do so. Accompa-

nied by Abernathy, Wyatt Tee Walker, and NAACP regional secretary Ruby

Hurley, King arrived in Albany on Friday afternoon to discover that Ander-

son had arranged two mass meetings, one at Shiloh Baptist and a second at

Mount Zion.

The speeches King gave that evening and the emotional procession that

followed him from Shiloh to Mount Zion drove a crowd of fifteen hundred

to near hysteria. After Hurley admonished the faithful to “keep your feet on

the ground although your heads are in the air,” King urged them to draw

upon the sustaining power of nonviolent struggle: “Say to the white man,

‘We will win you with the power of our capacity to endure,’ ” he advised.

Soulful spirituals, Albany-style freedom songs, and nearly two hours of elo-

quent testimony followed, and by the end of the evening nearly everyone was

overcome with emotion, including King and Dr. Anderson. When Anderson

rose to thank the SCLC leader, he could not resist adding an invitation to

spend the weekend marching for freedom in Albany. After a brief conference

in the pastor’s office, King agreed to stay in the city for at least another day—

an impulsive decision that had an immediate and unfortunate effect on the

ongoing negotiations with white leaders. Sometime after midnight Ander-

son, without consulting any of his colleagues, sent a brief telegram to Mayor

Kelley that sounded like an ultimatum: Frustrated with the slow pace of ne-

gotiations, the Albany Movement expected a favorable response to its de-

mands by 10:00

A.M. Saturday. Although the telegram did not say so explicitly,

Kelley and other city officials interpreted the message as a thinly veiled threat

to return to the strategy of mass protest. Angered by Anderson’s perceived

bluster, Kelley announced that the Albany Movement had broken off nego-

tiations with the city.

In the ensuing confusion, recriminations and factional suspicions threat-

ened to tear the Albany Movement apart. With some of its leaders noticeably

absent, the Andersons joined King, Abernathy, Walker, and 260 other march-

Oh, Freedom 473

ers on a Saturday afternoon prayer pilgrimage to city hall. None of the march-

ers, however, actually made it to the city hall steps. Intercepted by a large

force of local police and state troopers, all 265 marchers, including King,

were herded into an alley behind the city jail and placed under arrest. By

nightfall their arrests had swelled the number of movement demonstrators

behind bars to more than four hundred. As SCLC’s designated spokesman

on the Albany crisis, Abernathy accepted bail and returned to Atlanta on

Sunday morning. But King remained in jail as a symbol of SCLC commit-

ment to the Albany cause. “I will not accept bond,” he explained to reporters

from his cell at the Sumter County Jail. “If convicted, I will refuse to pay the

fine. I expect to spend Christmas in jail. I hope thousands will join me.”

Determined to take full advantage of King’s pledge, Abernathy announced

that SCLC was ready to spearhead a mass pilgrimage to Albany, and behind

the scenes Walker was busy soliciting funds and mobilizing local and na-

tional support for the SCLC initiative. Both men, however, were soon re-

buffed by a coalition of SNCC and Albany Movement leaders who resented

SCLC’s presumptuous declarations of authority and command. At a Sunday

press conference organized by Charles Jones and SNCC advisor Ella Baker,

Marion Page issued a firm denial that SCLC or any other outside group had

assumed leadership of the Albany Movement. Local movement leaders, he

insisted, had no plans to participate in an SCLC-sponsored pilgrimage or

any other mass demonstration that would prevent the Albany Movement from

resuming negotiations with city leaders.

This public rebuke would poison relations between SNCC and SCLC

in the coming months, but an unexpected development inside the Sumter

County Jail took some of the sting out of the situation. Minutes before Page’s

statement, King had changed his mind about remaining in jail. Worried that

his cellmate, Dr. Anderson, was on the verge of a nervous breakdown, King

told Walker “to get us out of here.” How Walker could do so without dam-

aging King’s reputation among movement stalwarts was unclear, but forces

beyond his or King’s control soon brought a timely if imperfect solution of

their dilemma. By Monday, December 18—the day of King’s trial—local,

state, and federal officials had reached a consensus that the only way to de-

fuse the crisis was to get King and the other demonstrators out of jail as soon

as possible. With James Gray, the conservative editor of the Albany Herald,

acting as a mediator, Robert Kennedy and Burke Marshall assured Mayor

Kelley that the Justice Department would refrain from interfering in the

Albany situation as long as it remained nonviolent. Encouraged by the re-

sumption of negotiations on Sunday evening, Kennedy and Marshall urged

Kelley to forge a compromise before King’s trial and conviction pushed the

crisis to a new level. After a frantic round of communications, movement and

city leaders worked out a preliminary settlement, just in time for Judge Abner

Israel to order a sixty-day postponement of King’s trial.

474 Freedom Riders

Under the terms of the agreement, King and all of the breach-of-peace

defendants were to be released immediately, most without the burden of post-

ing bond. Although the Freedom Riders and other “outside agitators” were

required to post hefty bail bonds, King endorsed the mass release of prisoners

as a precondition for future progress. The rest of the settlement, which

amounted to a verbal commitment to form a biracial desegregation commis-

sion, was more difficult to assess, he told reporters gathered on the courthouse

steps. But for now he felt that he could leave town with the comforting knowl-

edge that the city of Albany was finally moving in the right direction.

Unfortunately for King and the Albany Movement, this sanguine inter-

pretation of the situation was promptly contradicted by Chief Pritchett, who

denied that white leaders had agreed to anything beyond a willingness to

consider creating a biracial commission. Speaking for Mayor Kelley and the

city commission, Pritchett gave the distinct impression that King had de-

cided to leave Albany with or without a satisfactory settlement. Although

King and others later disputed Pritchett’s claim, the ensuing confusion put

King’s departure from Albany in a bad light. Coinciding with the collapse of

negotiations, his apparent retreat created a public relations disaster for SCLC.

Most reporters interpreted his involvement in Albany as a mistake; the New

York Herald Tribune, for example, labeled it “a devastating loss of face.” Many

movement leaders agreed, suggesting serious dissension within the move-

ment. Excluded from King’s postrelease press conference, Reagon and other

SNCC leaders could not hide their disdain for the cult of personality that

had prompted SCLC’s high-handed interference in Albany.

Although CORE officials tried to stay clear of the rising feud between

SNCC and SCLC, they too were concerned about the deteriorating situa-

tion in Albany. For them, however, the most troubling aspect of the Albany

crisis was the federal government’s tacit acceptance of Pritchett’s strategy of

indirection and delay. His insistence that the arrests at the Albany terminals

were designed to keep the peace, not to maintain segregation, was a trans-

parent attempt to justify non-compliance with the ICC order. Yet Justice

Department officials had not sought a Federal court implementation order

for Albany as they had in seven other recalcitrant communities. The fact that

the State of Georgia had filed a federal court suit challenging the ICC order

would, in all likelihood, eventually provide the Justice Department with a

legal lever to enforce desegregation in Albany and other Georgia cities. But

the department’s apparent willingness to treat the Albany situation as a spe-

cial case was still a troubling reminder of the political constraints that had

delayed civil rights enforcement in the past.

44

As the year of the Freedom Rides drew to a close, the unresolved crises

in Albany and McComb confirmed that, despite a general pattern of compli-

ance with the ICC order, there was a great deal of desegregation work left to

be done in the Deep South. “A well-advertised group of Freedom Riders

Oh, Freedom 475

may receive police protection,” columnist Anthony Lewis wrote in the New

York Times on December 3, “but it would probably still be a brave, indeed

foolhardy local Negro who sat down at the ‘white’ restaurant in an Alabama

or Mississippi bus terminal.” While he predicted “that acceptance of Federal

law is only a matter of time—in short, inevitable,” Lewis warned his readers

that “ending the deep-seated tradition of racial discrimination will be a long

and difficult process,” especially in places like Mississippi where “one should

beware of false optimism.” Indeed, even in the Upper South and border states,

where virtually all terminals, buses, and trains were desegregated, there were

pockets of dogged segregationist resistance, as a series of arrests at several

Route 40 restaurants demonstrated on December 16.

For the most part, however, movement leaders and administration offi-

cials were pleased with the overall response to implementation of transit de-

segregation. In most areas outright resistance had been replaced by a spirit of

resignation, and evidence of real progress could be seen in some of the South’s

toughest white supremacist strongholds. Even in Birmingham, where Bull

Connor sustained a spirited rear-guard political action against desegregation

of bus terminal restaurants, there was some grudging movement toward com-

pliance by mid-December. After Connor urged the city commission to re-

voke the Trailways restaurant’s license because it violated the city’s segregated

dining ordinance, an influential local businessmen’s group countered with a

call for compliance with federal law. On December 14 the Justice Depart-

ment tried to preempt Connor’s action by seeking a federal injunction against

any further interference with the ICC order in Birmingham. But five days

later—following a public hearing—the city commission voted unanimously

to revoke the license, all but forcing the federal courts to intervene. In early

January 1962 Federal District Judge Seybourn H. Lynne, a conservative seg-

regationist, surprised many local observers by issuing a temporary injunction

that nullified the commission’s action. Left with no legal alternative, Connor

and the commissioners conceded defeat on the narrow issue of segregated

transit facilities and transferred their energies to other fronts in the war against

desegregation and federal encroachment. While the broader struggle to pre-

serve Alabama’s white supremacist traditions went on, the battle of the Bir-

mingham bus terminals was over.

45

The prospects for compliance with the ICC order were also improving

in Mississippi, though here the situation was muddled by mixed signals from

the federal courts and by continued reliance on local breach-of-peace ordi-

nances. Even though the traditional Jim Crow signs had been removed from

the bus and rail terminals in Jackson and other cities, the threat of arrest

remained for anyone who attempted to desegregate white waiting rooms and

lunch counters. Lacking Pritchett’s political and diplomatic skills, and bur-

dened with the stigma of the Freedom Rider trials, Jackson officials made little

effort to conceal their segregationist intentions. Consequently, on December