Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

446 Freedom Riders

Following closing arguments on Thursday morning, the four-day hear-

ing came to an end, though not without a measure of confusion. Catching

almost everyone off guard, Judge Rives announced that he saw no need to

wait twenty days before issuing a ruling on the NAACP’s request for injunc-

tive relief. Although a permanent injunction could only come after the filing

of written briefs, he was ready to issue a preliminary injunction “removing

segregation signs from all waiting rooms,” prohibiting the arrest of Freedom

Riders under breach-of-peace statutes, and directing the Jackson City Lines

to cease enforcement of racial segregation on city buses. While he stopped

short of advocating an injunction against Greyhound, Trailways, or Attor-

ney General Patterson, Rives’s announcement sent a shudder through the

courtroom. Suddenly all eyes turned to Mize and Clayton, either one of whom

could turn Rives’s revolutionary proposal into a legal mandate. Those famil-

iar with the two Mississippi jurists had no reason to believe that Rives’s judg-

ment would be sustained, but some segregationists were disappointed when

Clayton refused to comment and Mize offered only a curt statement that he

was “not prepared to express any opinion or give any views at this time.”

28

In the days following Rives’s announcement, there was considerable

speculation about the likelihood and implications of a preliminary injunc-

tion. In Nashville, where SCLC was wrapping up its annual three-day con-

vention, even a slight chance that such an injunction might be granted was

greeted as welcome news. Three days earlier, on the eve of the convention,

Martin Luther King had hailed the ICC ruling as proof that the Freedom

Riders’ struggle “had not been in vain.” The desegregation of buses and ter-

minals was imminent, he insisted, and the nonviolent movement would soon

move on to other challenges, including the goal of doubling the number of

black voters in the South by the end of the year. “We are willing to suffer,

sacrifice and die, if necessary, to make that freedom a reality,” he declared,

adding that the struggle for racial equality was actually a fight “to save the

soul of the nation.”

Sadly, by the time the convention opened on Wednesday, the shocking

news of Herbert Lee’s death had already tempered the optimism and eupho-

ria of the day before. Over the next two days conflicting reports about the

developing situations in Jackson and McComb only added to delegates’ anxi-

eties. On Wednesday evening, during the intermission of an SCLC benefit

concert featuring Harry Belafonte, Miriam Makeba, and the Chad Mitchell

Trio, the convention paid tribute to the Freedom Rides by awarding five-

hundred-dollar scholarships to ten student Riders—including John Lewis,

Jim Zwerg, and six of the students expelled from Tennessee A&I. But not

even the beaming faces of the young Riders and the congratulatory rhetoric

that washed over the crowd could disguise a growing apprehension about the

future of the nonviolent movement.

29

The mixed signals coming out of Mississippi complicated SCLC’s plans

for an expanded program of direct action. In a report delivered to the SCLC

Oh, Freedom 447

board just prior to the opening of the convention, executive director Wyatt

Tee Walker proposed two major changes in organizational activity. The first

proposal suggested that SCLC might be more effective as an organization

made up of individual members, as opposed to its present status as a regional

confederation of local groups. Avoiding direct competition with the NAACP

had been SCLC policy since its founding in 1957, but Walker urged the

board to reconsider its decision to forgo the financial and programmatic ben-

efits of mass membership. The second proposal was to add a “Special Projects

Director” to the SCLC staff, someone who could develop direct action into a

“Southwide mass movement.” The obvious choice for this position, according

to Walker, was Jim Lawson, the architect of the Nashville Movement.

After King endorsed the proposal, the board authorized Walker to hire

Lawson, who soon found himself explaining SCLC’s new initiative to re-

porters. Although he and Walker had not yet had time to work out the de-

tails of the initiative, Lawson decided to provide the reporters with an

expansive vision of SCLC’s plans. Over the coming months, he declared, the

organization planned to recruit a nonviolent army of ten thousand commit-

ted activists, each willing to put his or her body on the line, or in jail if need

be. In the tradition of Gandhi’s followers, SCLC’s nonviolent soldiers would

attack social injustice wherever they found it, including the darkest recesses

of the Deep South. Until white Americans repudiated their attachment to

racial privilege and discrimination, sit-ins, stand-ins, and other acts of non-

violent resistance would be an unavoidable fact of life. When asked to con-

firm Lawson’s lofty prediction, Walker hedged, acknowledging that the goal

of ten thousand activists would take several years to achieve. In the short run,

he suggested, a cadre of 100 to 150 would suffice.

The disagreement over numbers reflected something more than a mis-

communication between Lawson and Walker. The Tennessee preacher’s

conception of the SCLC project represented the most ambitious and idealis-

tic version of nonviolent direct action. Unlike Walker and most other move-

ment leaders, Lawson viewed nonviolence as an all-encompassing philosophy.

For him the strategic objectives of legal and political leverage were less im-

portant than the search for the “beloved community.” Sending several hun-

dred Freedom Riders into Mississippi was an instructive exercise in nonviolent

discipline and a means of forcing politicians to pay attention to the freedom

struggle, but Lawson envisioned the nonviolent movement of the future on a

much grander scale. Effecting a moral revolution in America would require

the direct participation of thousands of activists and a deeper and broader

experience with sacrifice and unmerited suffering. Nothing less than filling

and refilling the jails over and over again and bringing the normal activities

of the nation to a halt would do.

How the nation would respond to nonviolent activity of this magnitude

was unclear, but many movement activists regarded Lawson’s ambitious pro-

posal as a formula for mass suicide, or at the very least as a strategic blunder

448 Freedom Riders

that would reduce the movement’s effectiveness. In private conversations with

members of the SCLC board, Lawson himself expressed doubts about the

current viability of mass direct action in the Deep South, especially in Missis-

sippi. The murder of Herbert Lee and the general spirit of massive resistance

among white Mississippians made him wonder if the state was ready for non-

violence on a mass scale. As committed as he was to the strategy of nonvio-

lent confrontation, he did not want to squander the movement’s resources in

a premature effort that had little or no chance of success. Replicating the

nonviolent workshops that had worked so well in Nashville required a de-

gree of social space that many parts of Mississippi had yet to achieve. With

this in mind, even Lawson began to shy away from an unhealthy emphasis on

Mississippi.

30

The intractable nature of white supremacy in Mississippi was also a ma-

jor topic of discussion at a SNCC meeting held in Atlanta during the last

weekend of September. The gathering in Atlanta was the first general meet-

ing of SNCC leaders since the retreat at Highlander in mid-August, and the

first since Ed King had stepped down as SNCC’s executive secretary in mid-

September. Virtually the entire coordinating committee, as SNCC’s leaders

loosely called themselves, was on hand, including a carload of weary activists

from McComb. SNCC’s chairman, Chuck McDew, decided to stay in

McComb and skip the meeting, but Jim Forman, who had recently moved to

Atlanta to fill in for the departing King, was there to act as an informal coor-

dinator. The first order of business was to replace King as executive secre-

tary, and after Ella Baker declined the position Forman agreed to take it,

even though he had serious misgivings about SNCC’s organizational struc-

ture and prospects. As Forman later revealed, the reorganization at High-

lander had not eliminated the “factional fights over direct action versus voter

registration” or the radical democratic ethos that gave SNCC meetings a

discursive and disorderly quality. While the students’ commitment to the

cause of civil rights was undeniable and impressive, Forman found their free-

form discussions of philosophy and strategy to be unproductive and even a

bit unnerving.

Some, including Bob Moses, had little patience for organizational nice-

ties. Early in the meeting Moses announced that he was ready to return to

McComb, where he felt he was needed. Although he eventually agreed to

stay for at least another day, the volatile situation back in Mississippi weighed

on his mind. As he, Charles Sherrod, and other members of the McComb

group explained, the struggle in southwestern Mississippi was like nothing

they had ever experienced before. The responsibility of asking a poor black

farmer to put his life on the line for the right to register to vote was proving

to be a heavy burden. Everyone had expected Mississippi to be tough, but no

one had anticipated a scene such as the one that Moses and McDew encoun-

tered at Herbert Lee’s funeral when a distraught widow looked them in the

eye and screamed: “You killed my husband! You killed my husband!”

Oh, Freedom 449

This and other stories related to the ongoing struggle in Mississippi had

a noticeable impact on the deliberations in Atlanta. In the end, however, the

students refused to be cowed either by violent resistance or their own fears.

Shelving a plan to dispatch field secretaries to various movement centers

across the South, they formulated a long-range project known as Operation

MOM, March (or Move) on Mississippi. For the foreseeable future, SNCC’s

entire direct action wing would be assigned to Mississippi. Headquartered in

Jackson, Operation MOM would include local projects in McComb and other

targeted communities where SNCC volunteers could develop “a locally based

attack on the state power structure.” The students also agreed to expand the

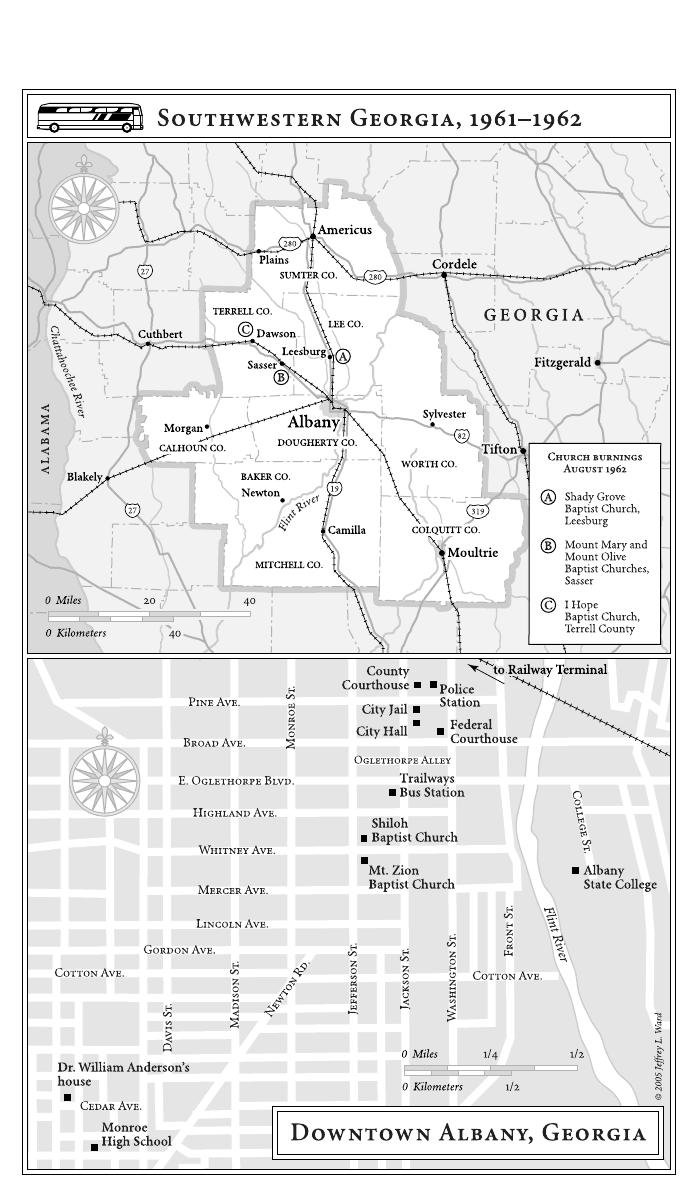

efforts of the voting rights wing, especially in southwestern Georgia, where

Sherrod had already explored the prospects for a pilot project. Sherrod and

Cordell Reagon, a Freedom Rider from Nashville, would relocate to the city

of Albany, which had little experience with civil rights activism but nonethe-

less had the potential to become a major center of movement activity, ac-

cording to Sherrod. Others were not so sure about Albany’s prospects, but

the enthusiasm and renewed sense of purpose that emerged from the Atlanta

meeting gave a measure of hope even to the most pessimistic among them.

31

FOR SHERROD AND REAGON, as for many of the SNCC activists, this spirit of

optimism would be sorely tested during the first week of October. On Mon-

day, October 2, they drove back to McComb with Moses, not knowing ex-

actly what had transpired there over the weekend. Upon arriving at the SNCC

Masonic Temple office in McComb, they learned that the five students ar-

rested during the Woolworth’s sit-in on August 26 were about to be released

on bond. Two of the students, Brenda Travis and Ike Lewis, were still en-

rolled at Burgland High, McComb’s all-black junior and senior high school.

But when they tried to return to their classes on October 4, the principal

expelled them for participating in an illegal demonstration. Other students

at Burgland, anticipating the principal’s decision, had already made prepara-

tions for a mass walkout, and within minutes of the expulsion more than a

hundred students were walking down the street with the intention of march-

ing the full eight miles to the county courthouse in Magnolia. Along the way

they stopped at the Masonic Temple to pick up protest signs they had made

the night before; while at the temple, they sought counsel from several SNCC

workers, including Moses, McDew, Reagon, and Marion Barry. Concerned

that the students’ parents would blame SNCC if the march led to mass ar-

rests or violence, Moses and McDew urged the marchers to disband. But

Reagon and Barry advised the students to march on regardless of the conse-

quences. When it became clear that the students were determined to march,

Moses and McDew agreed to accompany them to Magnolia, even though

they had grave doubts about the wisdom of provoking local authorities with

a hastily planned protest. Ironically, Reagon and Barry, the two SNCC lead-

ers who enthusiastically supported the march, remained at the temple office.

450 Freedom Riders

Moses’s fear of losing most of his staff in a single round of arrests was

reason enough to limit the number of SNCC marchers, but the students’

plan to walk all the way to the county courthouse also posed a daunting physical

challenge to potential volunteers. To Moses’s relief, the students abandoned

the original plan once they reached the outskirts of McComb; turning back

toward downtown, they headed for the McComb city hall, where they hoped

to find someone who could overrule the expulsion of Travis and Lewis. Along

the way the marchers tried to ignore the taunts of white bystanders, but by

the time the march reached city hall a swelling crowd of angry protesters had

surrounded the building. Although the McComb police were also out in force,

the officers on duty refused to intervene when several members of the mob

began to beat Bob Zellner, the only white participant in the march.

A recent graduate of Huntingdon College, a small Methodist school in

Montgomery, Zellner had joined the SNCC staff on September 1 after be-

ing recruited by Anne Braden and Jim Dombrowski of the Southern Confer-

ence Education Fund (SCEF). Braden and Dombrowski had been looking

for a talented organizer who could recruit liberal white students on Southern

campuses, and Zellner ably fulfilled their expectations, visiting more than

twenty campuses during his first month on the road. McComb, however,

proved to be a costly diversion. Having witnessed the attack on Jim Zwerg

and other Freedom Riders in Montgomery in May and fearing that his pres-

ence might exacerbate an already volatile situation, Zellner was initially reluc-

tant to join the October 4 march. As Moses and the students departed, though,

he could not resist the temptation to join them. This decision nearly cost him

his life. During the confrontation at city hall, Moses and McDew tried to shield

him from the advancing mob, but the police pulled them away, leaving him at

the mercy of several attackers who gouged his eyes and eventually kicked him

into unconsciousness. In the end, the only thing that saved him was a belated

police order to arrest all of the marchers, many of whom had climbed the city

hall steps to pray. By nightfall the police had carted 116 students and 3 SNCC

workers off to jail, including a stunned and bleeding Zellner.

Although the police quickly dropped the charges against 97 students who

were under the age of eighteen, 19 “adult” students and Moses, McDew, and

Zellner were prosecuted for breach of peace and contributing to the delin-

quency of minors. The next morning the police arrested Reagon, Sherrod,

and C. C. Bryant as accomplices, temporarily leaving Charles Jones as the

only SNCC worker remaining free. Thanks to a five-thousand-dollar contri-

bution by Harry Belafonte, all of the defendants were soon released on bond,

but bail brought no relief from the wrath of black parents who blamed SNCC

for leading their children astray. When the Burgland principal threatened to

expel any student demonstrator who refused to sign a pledge promising to

refrain from additional protests, some parents supported their children’s de-

cision to join a second walkout, but most felt that the walkouts were counter-

productive and dangerous. SNCC, they believed, had exploited and incited

Oh, Freedom 451

their children for political purposes. Before long, even Bryant concluded that

the SNCC visitors had worn out their welcome. Convinced that SNCC cam-

paign was doing more harm than good, he asked Medgar Evers and the

NAACP to assume control of the McComb voting rights project.

Despite serious misgivings about SNCC’s aggressive tactics, Evers po-

litely deflected Bryant’s request, preferring to limit the NAACP’s involve-

ment to legal representation of the defendants. At an October 10 rally held at

the Masonic Temple, Evers endorsed the students’ continued defiance. But

he had second thoughts about the wisdom of the students’ actions after an

October 11 march provoked a violent response from local whites. While the

marchers themselves escaped injury, two college journalists covering the

march, National Student News correspondent Paul Potter and future anti-war

activist and recent University of Michigan graduate Tom Hayden, were

dragged from their car and beaten. Evers and other NAACP leaders also

grew concerned when the SNCC workers organized an alternative “freedom

school” known as “Nonviolent High.” Recruiting many of the expelled stu-

dents, Moses, McDew, and Dion Diamond taught classes for three weeks

until their efforts were cut short by a trial that put all twenty-two defendants

behind bars.

32

On the last day of October, the day before the ICC order was scheduled

to go into effect, Moses, McDew, Zellner, and the student defendants re-

ceived jail sentences ranging from

four to six months. During the

trial the presiding judge had char-

acterized the students as “sheep

being led to the slaughter” by “out-

side agitators,” and he and other

local white leaders showed no

sympathy when the defendants

were unable to raise bail. It took

SCEF president Jim Dombrowski

more than a month to raise the re-

quired thirteen thousand dollars in

bond money, and the three SNCC

leaders and most of the convicted

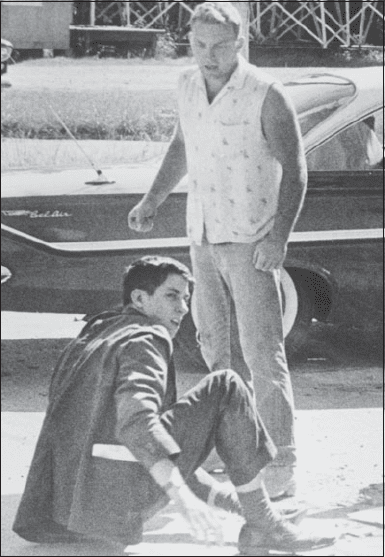

Freelance reporter and University

of Michigan student activist Tom

Hayden struggles to get up after

being assaulted by Carl Hayes

(standing) and other local whites

protesting a pro-integration march

in McComb, Mississippi, October

11, 1961. (Bettmann-CORBIS)

452 Freedom Riders

students languished in the Magnolia jail until early December. By then the

McComb movement was in shambles, having run “head-on into the stone

wall of absolute police power,” as historian Howard Zinn later put it.

While Moses and his colleagues were behind bars in Magnolia, the black

community in nearby McComb retreated behind the familiar walls of racial

accommodation, which in turn encouraged the local white community to

reassert its traditional dominance. When six Freedom Riders traveled to

McComb in early November to test compliance with the ICC order, they

were fortunate to escape with their lives. Soon even Moses reluctantly con-

ceded that the town was not quite ready for SNCC’s assertive approach to

direct action. Following his release on December 5, he relocated to Jackson,

partly because several of the Burgland students had moved there to attend

classes at Campbell Junior College, but primarily because there was no longer

much that he could do in McComb. Philosophical in defeat, he proposed a

shift from the “dusty roads” of southwestern Mississippi to the “dusty streets”

of Jackson. As he put it, having gotten their “feet wet” in McComb, the young

activists of SNCC “now knew something of what it took to run a voter regis-

tration campaign in Mississippi.”

33

Among the many valuable lessons learned in McComb was the realiza-

tion that voting rights agitation was just as dangerous as other forms of direct

action. Contrary to the expectations of Justice Department officials, most

white segregationists seemed to put black voter registration efforts in the

same category as sit-ins and freedom rides. Regardless of the specific issue at

hand, a fixation on a broad-based conspiracy of “outside agitators” invali-

dated the claim to legitimate dissent. Later in the decade—following the

1963 March on Washington, the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965, and

other expressions of movement strength and solidarity—the notion of the

civil rights movement’s legitimacy would become a grudgingly accepted fact

of life among white Southerners. In 1961, however, such acceptance was rare,

especially in the Deep South, where racial demography and the dictates of

caste and class kept open dissent to a minimum. Unbeknownst to all but a

few whites, and to many blacks as well, there were untapped sources of move-

ment strength, even in the most remote black communities. But the condi-

tions had to be right, as they were in the wake of the Freedom Rides, for this

unrealized potential to become a meaningful part of the political landscape.

The movement that emerged in Albany, Georgia, during the fall of 1961

demonstrated just how quickly an external provocation could energize inter-

nal dissent. Within days of their arrival in a seemingly placid community of

sixty thousand, Sherrod and Reagon turned a series of church prayer meet-

ings at Shiloh Baptist Church into an insurgent revolt against racial compla-

cency. With the black proportion of the local population hovering around 40

percent and a tradition of nonconfrontational race relations, Albany supported

a struggling NAACP branch with a declining membership. At the height of

its influence, in the years following World War II, the Albany branch had

Oh, Freedom 453

454 Freedom Riders

mounted a successful voter registration drive that produced an expectation

of black participation in local public life, but a decade and a half later the city

remained rigidly segregated.

In May 1961 Tom Chatmon, a local black businessman, organized an

NAACP Youth Council with the intention of nudging white officials toward

gradual reform. Like Martin Luther King, Chatmon had attended Morehouse

College during the late 1940s, but he did not share King’s faith in militant

direct action. Instead, he counseled Albany’s black youth to be patient and

ever mindful of their elders’ vulnerability. Alarmed by rumors of SNCC’s

growing influence among the Youth Council members, who were reportedly

enthralled by tales of Freedom Rides and sit-ins, Chatmon warned local and

regional NAACP leaders that Sherrod and Reagon were playing with fire.

Though not unmindful of Chatmon’s limitations, Vernon Jordan, Georgia’s

NAACP field secretary, shared the Youth Council leader’s concerns and did

what he could to discourage any further SNCC interference. In mid-October

several local NAACP leaders informed the two troublesome SNCC work-

ers that they were no longer welcome in the city, but Sherrod and Reagon,

confident that something significant was stirring among their young fol-

lowers, had no intention of leaving. Indeed, several of the most adventur-

ous Youth Council members had already informed Chatmon that they

planned to participate in a desegregation test at the Albany Trailways ter-

minal on November 1.

Fearing that he was about to lose all credibility with his charges, Chatmon

reluctantly agreed to consider the idea, and in late October he met with

Sherrod and Reagon to work out a compromise that would protect both the

students and the local reputation of the NAACP. All agreed that there would

be no mention of NAACP involvement, and that the students would suspend

the test if and when arrests became imminent. Though somewhat uncom-

fortable with the latter restriction, Sherrod and Reagon decided not to force

the issue. Despite the NAACP’s foot-dragging, their organizational efforts

were progressing much faster than they had hoped, and they were eager to

share the good news with their colleagues in Mississippi. On October 30

they boarded a bus for a whirlwind trip to McComb, where they planned to

discuss the situation in Albany and to attend the trial of Moses, McDew, and

Zellner. Two days later, if all went well, they would return to Albany as Free-

dom Riders testing the ICC order. The students, Chatmon promised, would

meet them in the white waiting room of the Trailways station for a joint test.

Sherrod and Reagon returned to Albany via the SNCC office in Atlanta,

where they met with Forman and Charles Jones on Halloween night. Forman

and Jones were busy making final preparations for their own ICC test—an

early-morning visit to Jake’s Fine Foods Restaurant at the downtown Atlanta

Trailways station—but they offered Sherrod and Reagon an official observer

for the four-hour bus run to Albany. Salynn McCollum, the veteran Free-

dom Rider from Nashville’s Peabody College who had been hired as one of

Oh, Freedom 455

SNCC’s first white staff members, was eager to go along, and when the

morning bus to Albany left the Trailways station she was on it. Avoiding

any direct contact with Sherrod and Reagon, she sat quietly among the

white passengers as the drama of Georgia’s first compliance test unfolded.

Halfway along the route, the bus was pulled over to the side of the road by

Georgia state troopers who walked up and down the aisle before waving

the driver on. Although Sherrod and Reagon were sitting in the front sec-

tion behind the driver, there were no arrests, but it was clear that authori-

ties in Atlanta and Albany knew that a Freedom Ride was in progress.

Arriving at the Albany Trailways station at 6:30 in the morning, Sherrod

and Reagon, with McCollum trailing well behind, strolled into the waiting

room expecting to see the familiar faces of the Youth Council volunteers.

To their surprise and dismay, however, not a single volunteer was there to

greet them. Fearing that the students were already in jail, they looked warily

at the police patrolling the waiting room, then quietly exited the station in

search of their missing disciples. After a few frantic phone calls, they learned

that there had been no arrests and no attempt to desegregate the station.

The students had stayed away because they had become convinced that

local white supremacists planned to beat or even kill them if they tried to

test compliance with the ICC order.

In actuality, Albany’s police chief, Laurie Pritchett, had convinced Mayor

Asa Kelley and the city commission that the best way to handle Freedom

Riders was to avoid violence at all costs. At a special closed meeting of the

city commission on October 30, Pritchett had outlined a strategy patterned

after that of the Jackson police: Vigilante violence would be preempted by

timely arrests, and the basis for all Freedom Rider arrests would be the main-

tenance of public order, not the violation of segregation laws. That the ru-

mor mill in the black community suggested just the opposite spoke volumes

about the underlying insecurities and fears that dominated race relations in

the city. How Sherrod and Reagon were able to quiet such fears is not alto-

gether clear, but by midafternoon they had convinced nine Youth Council

members to violate the sanctity of the same white waiting room they had

been afraid to enter only hours before.

With the two SNCC workers watching from a nearby street corner, and

with McCollum observing from an even closer vantage point, the nine stu-

dents walked into the waiting room to confront the unjust power of the white

establishment. “The bus station was full of men in blue,” Sherrod later wrote,

“but up through the mass of people, past the men with guns and billies ready,

into the terminal they marched, quiet and clean. They were allowed to buy

tickets to Florida but after sitting in the waiting room they were asked to

leave under threat of arrest.” Although they did so immediately, the signifi-

cance of what they had already accomplished soon became apparent. By stand-

ing up for their constitutional rights, however briefly, they had broken the

spell of unchallenged dominance. As Sherrod put it, “From that moment