Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

486 Freedom Riders

family. Hoping to embarrass not only the president and the attorney general

but also their younger brother, Ted, who was in the midst of a race for a seat in

the U.S. Senate, Capitol Council president Amos Guthridge distributed re-

cruitment posters indicating that “President Kennedy’s brother assures you a

grand reception to Massachusetts. Good jobs, housing, etc. are promised.”

When, as expected, the actual reception accorded the scores of black migrants

to Hyannis proved to be something less than grand, Guthridge declared that

his experiment had confirmed the immutable nature of racial segregation. Here,

as elsewhere, there were individual acts of kindness that belied the Citizens’

Councils’ sweeping claims that all white Northerners were racially prejudiced.

But the generally inhospitable response of Northern officials—which included

Massachusetts governor John Volpe’s request for federal legislation outlawing

the Reverse Rides—allowed the Citizens’ Councils to score propaganda points

that were trumpeted by conservative commentators north and south. “Listen

to them squirm!” advised the Chicago-based columnist Paul Harvey. “The

hypocrisy of pompous Northern do-gooders has never been more apparent.”

More sympathetic observers pointed out that factors other than racism were

involved—that Volpe and others were understandably worried that a flood of

impoverished migrants would overwhelm an already overburdened welfare

system in unprepared Northern communities—but it was difficult to counter

the general impression that Northern hypocrisy had been exposed.

The deteriorating situation in Hyannis was especially embarrassing: Most

of the black migrants moved on as soon as they found an alternative, and only

one family of Reverse Riders remained there three years later. But the experi-

ences of the Reverse Riders sent to other communities—from Concord, New

Hampshire, to Pocatello, Idaho—were not much better. By midsummer, the

negative publicity surrounding the general disillusionment of the approximately

two hundred blacks who had joined the Reverse Freedom Rides had convinced

almost everyone, including most Citizens’ Council leaders, that the program

had run its course. Strapped for funding, the participating councils quietly with-

drew their offers to sponsor additional Riders. In September Singelmann pro-

moted a desperate plan to revive the program by dispatching unemployed black

Southerners to the hometowns of Hubert Humphrey and other liberal politi-

cians during the Christmas season, and for several months thereafter he con-

tinued to solicit funds for the expressed purpose of resuming the Rides. But

mercifully his efforts proved futile. The sordid affair that the New York Times

had aptly labeled “a cheap trafficking in human misery” was over.

13

THE REVERSE FREEDOM RIDES never quite caught on in Georgia, where the

White Citizens’ Councils were less powerful than in Louisiana or Missis-

sippi. Only the chapter in Macon—where a bus boycott forced the deseg-

regation of local transit facilities in March 1962—came forward to sponsor

black migrants, and fewer than a dozen Reverse Riders actually left the

Epilogue: Glory Bound 487

state. While many white Georgians undoubtedly sympathized with the ef-

fort to embarrass Northern liberals, few seemed willing to engage in public

manifestations of revenge or defiance in the wake of the Freedom Rides. In

many areas of the state, this spirit of restraint turned out to be a temporary

flirtation, and later in the decade a powerful political backlash against mod-

erates perceived to be soft on segregation put the race-baiting demagogue

Lester Maddox in the governor’s mansion. But in 1962 political modera-

tion was on the upswing in Georgia, which appeared to be moving away

from its more truculent Deep South neighbors on matters of race and re-

sistance. Led by an image-conscious Atlanta business community and pro-

pelled by Baker v. Carr, a landmark March 1962 Supreme Court decision

that struck down a long-standing county unit system giving unfair advan-

tage to rural voters, the state had reached a “turning point,” as former presi-

dent Jimmy Carter later put it.

Elected to the state senate in the fall of 1962, in his first race for public

office, Carter was just one of the moderates to come to the fore in that piv-

otal year. In the Democratic gubernatorial primary, reform-minded Carl

Sanders of Augusta defeated the arch-segregationist former governor Marvin

Griffin, thanks to strong support from both white and black voters in metro-

politan Atlanta. In the capital city as a whole, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. presided

over an increasingly progressive political culture, and in one downtown dis-

trict Leroy Johnson became the first black since Reconstruction to be elected

to the state senate. Die-hard segregationists and conservative politicos re-

mained dominant throughout rural and small-town Georgia, and even in

Atlanta the desegregation process had barely begun. But with a cluster of

Atlanta-based civil rights organizations—notably SCLC, SNCC, and the

Southern Regional Council—providing close scrutiny and steady pressure,

and with Ralph McGill’s Atlanta Constitution taking a stand against racial

extremists, the prospects for future progress in the state looked bright in the

year following the Freedom Rides.

14

There was, however, one major exception to this optimistic forecast—

one white community hell-bent on countering the overall trend toward

moderation and desegregation. If Atlanta represented the progressive end

of the spectrum in Georgia, Albany stood at the opposite end as a symbol

of white intransigence and black frustration. Here, in the wiregrass low-

lands of southwestern Georgia, there was no letup in the bitter struggle

between an ultra-segregationist local power structure and the determined

Albany Movement. Though hobbled by dissension following King’s em-

barrassing departure in December 1961, Albany’s black activists regrouped

in early January, coalescing around an effort to overturn the dismissal of

forty student demonstrators from Albany State College. Issues related to

the Freedom Rides and segregated transit facilities continued to simmer,

and on January 12 the arrest of eighteen-year-old Ola Mae Quarterman for

488 Freedom Riders

refusing a driver’s order to move to the back of a city bus prompted the

Albany Movement to extend its month-old boycott of downtown stores to

the city’s private municipal bus line. Sustained by a car pool similar to the

one used by the Montgomery Improvement Association in 1956, the boy-

cott soon forced the financially strapped bus company to ask the city com-

mission for a subsidy.

In the meantime, segregation remained in force, and on January 18

Charles Sherrod and Charles Jones were arrested for “loitering” after a brief

sit-in at the Trailways station’s lunch counter. Five days later, at the first meet-

ing of the newly elected city commission, Dr. William Anderson and Marion

Page appeared before the commissioners to request a written reaffirmation

of the December 18 oral agreement, which had authorized the creation of a

biracial committee and the complete desegregation of local transit facilities.

But Mayor Asa Kelley adjourned the meeting without committing to the

reaffirmation. Subsequent negotiations between the Albany Movement and

the bus company produced promises to maintain integrated seating and to

hire black drivers, but on January 29 the city commission refused to endorse

the agreement and rejected the request for a subsidy. Two days later the hard-

liners on the commission went even further, formally repudiating the De-

cember 18 agreement and reprimanding Mayor Kelley for coddling the Albany

Movement. At a second meeting later in the day, the commission, with only

Mayor Kelley dissenting, reiterated its refusal to allow the bus company to

desegregate its facilities. Facing bankruptcy and caught in the whipsaw of

political posturing, the company suspended all operations at midnight.

The hardening of the city commission’s position and the suspension of

bus service on January 31 initiated a series of confrontations that kept the

city in turmoil until late summer. But Chief Laurie Pritchett, the main archi-

tect of Albany’s response to movement activists, made sure that the turmoil

stopped short of mass violence. Throughout the spring and summer of 1962,

he maintained a consistent strategy of obstructing desegregation with breach-

of-peace arrests that avoided outright defiance of the ICC order. In late March,

during the trial of the Freedom Riders arrested on December 10, the Albany

police dragged Sherrod, Bob Zellner, Tom Hayden, and Per Laursen out of

the courtroom after they tried to sit together as an integrated group, but for

the most part Pritchett and his men used as little force as possible when

arresting and controlling demonstrators. Armed with weekly and sometimes

daily briefings on Gandhian discipline, the uniformed defenders of Albany’s

white supremacist status quo tried to offset the moral force of nonviolent

struggle by responding in kind—by enforcing segregation with as much cour-

tesy and restraint as the situation allowed.

In this way, Pritchett kept both the Kennedy administration and the Al-

bany Movement off balance, forestalling federal intervention and disrupting

the momentum of mass protest. In neighboring Terrell County, where Sher-

iff Zeke Mathews tried to intimidate Sherrod and other voting rights work-

Epilogue: Glory Bound 489

ers with thinly veiled threats of violence, the administration was much more

assertive, filing a formal complaint against Mathews after a New York Times

reporter quoted one of his deputies exclaiming, “We’re going to get some of

you,” to a group meeting in a black church. And in both Terrell and nearby

Lee County, a series of black church burnings during the summer of 1962

triggered an ongoing FBI investigation and several arrests. But in Albany

itself Pritchett and his men were able to maintain an aura of peaceful, if firmly

segregated, coexistence.

15

The effective and confounding nature of Pritchett’s strategy became

obvious in July, when King and Abernathy returned to Albany to serve forty-

five-day jail terms. Choosing jail instead of paying $178 fines, the SCLC

leaders hoped that their incarceration would re-energize the local movement,

refocus media attention on Albany, and perhaps force the Kennedy adminis-

tration to intervene on the movement’s behalf. The drama surrounding the

sentencing and King and Abernathy’s first night in jail was all that movement

leaders hoped it would be. But the Albany saga took a strange turn during the

next two days—first when a movement march and rally deteriorated into a

violent confrontation between the police and brick-throwing teenagers, and

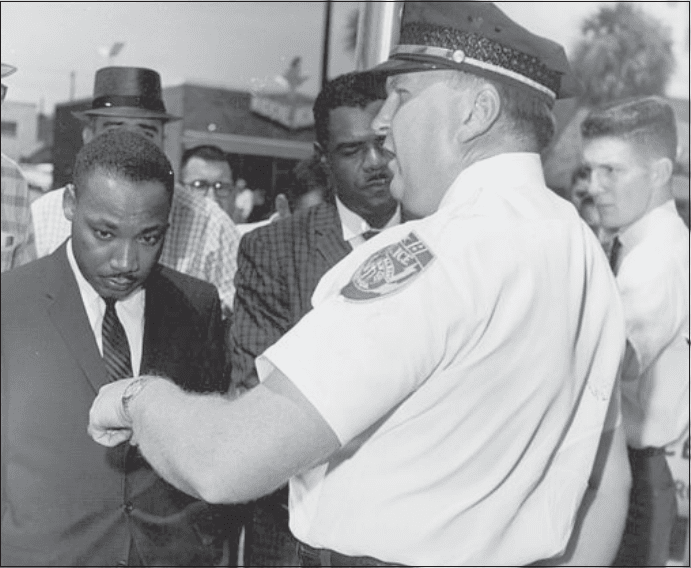

The arrest of Martin Luther King Jr. by Police Chief Laurie Pritchett in Albany,

Georgia, July 27, 1962. (AP Wide World)

490 Freedom Riders

later when an “unidentified black man,” later discovered to be an agent of

Pritchett’s, paid King’s and Abernathy’s fines. With the SCLC leaders’ un-

expected release, the fragile coalition of local and national civil rights organi-

zations began to unravel.

After several days of confusion and indecision, and after SNCC activists

questioned his motives as well as his courage, King reluctantly agreed to lead

a demonstration that would almost certainly put him back in jail, but on July

20 District Judge Robert Elliott, a conservative Kennedy appointee and ar-

dent segregationist, issued an injunction banning any additional civil rights

marches in Albany. While this was hardly the federal intervention that he

had sought, King promptly announced that he would abide by Elliott’s rul-

ing and call off the planned marches. This decision infuriated Charles Jones,

Jim Forman, and several other SNCC activists who confronted King in an

emotional meeting that revealed deep divisions between SCLC and the stu-

dent movement. Tempers cooled, however, four days later when Federal

Circuit Judge Elbert Tuttle rescinded Elliott’s injunction.

Rearrested with ten others following a July 27 march, King spent the

next two weeks in jail, still hoping that his high-profile arrest would force the

Justice Department to exert enough legal pressure to break the stalemate in

Albany. By this time, however, the Albany Movement was losing steam, and

city officials were growing increasingly confident that they were on the verge

of winning a “war of attrition.” On August 10, with the number of available

marchers dwindling and with little prospect of federal intervention, move-

ment leaders announced the suspension of demonstrations. In return, city

officials arranged for the immediate release of King and Abernathy, both of

whom returned to Atlanta the next day.

Later in the month, after white leaders made it clear that they had no

interest in any further negotiations with the Albany Movement, demonstra-

tions resumed on a limited scale. And on August 28, an SCLC-sponsored

“Prayer Pilgrimage” brought seventy-five clerical leaders—including several

former Freedom Riders—to the city in an effort to dramatize the plight of

Albany blacks. All 75 were arrested following a prayer vigil on the city hall

steps, and 11 remained in jail for several days after refusing to accept bail.

But not even the incarceration of nearly a dozen nationally prominent minis-

ters and rabbis could move the Kennedy administration to action—or regen-

erate the flagging spirit of the Albany Movement. In southwestern Georgia,

the era of mass protest was essentially over, even though cradle-to-grave seg-

regation remained in force. While Sherrod and the SNCC voting rights

project remained active in the area for another year, the broad-based Albany

Movement went into permanent decline during the fall of 1962. In 1963 the

Albany Movement secured a Federal court injunction ordering the desegre-

gation of all municipal facilities, including bus terminals, but full implemen-

tation of the order did not come for several years. Indeed, in the case of

Epilogue: Glory Bound 491

transit desegregation, the injunction proved useless because the municipal

bus system was no longer in operation.

Of all the civil rights projects related to the Freedom Rides, Albany prob-

ably produced the fewest tangible gains. Observers inside and outside the

movement, both then and later, often characterized the Albany Movement’s

collapse as the national civil rights struggle’s first major defeat. At the same

time, however, there has been widespread and justified appreciation of the

intangible benefits of the Albany episode. In Albany’s black community, where

individual empowerment and bold assertions of equal rights had been rare

prior to 1962, sustaining eleven months of demonstrations and capturing the

nation’s attention brought a collective sense of pride, even in the face of

defeat. Most significantly, in the broader context of an evolving national civil

rights movement Albany prompted a searching self-evaluation that took the

movement—especially SCLC and SNCC—to a higher level of tactical and

strategic consciousness. Outlined in an influential Southern Regional Coun-

cil report and discussed at numerous movement gatherings in late 1962 and

early 1963, the lessons learned in Albany—notably, the limitations and vul-

nerability of nonviolent protest, the difficulty of melding local and national

civil rights organizations, the pitfalls of being drawn into a campaign without

careful advance planning and well-defined goals, the indispensability of fed-

eral support, and the capacity of shrewd segregationist leaders to undercut

the movement’s moral imperatives in the eyes of reporters and politicians—

would prove valuable to King and other movement leaders in the months

and years to come.

16

THE ALBANY EPISODE was also instructive to white segregationists, especially

in Alabama, where the unintended consequences of mob violence and heavy-

handed political resistance were becoming apparent. For all but the most

myopic extremists, the sharp contrast between Albany’s Laurie Pritchett and

Birmingham’s Bull Connor was revealing. Unlike Pritchett, Connor had

played into the hands of nonviolent civil rights activists by turning himself

into a symbol of segregationist lawlessness and unrestrained racial hatred. By

relinquishing the moral high ground to martyred Freedom Riders, he and

his Klan accomplices forfeited whatever chance they had of persuading the

outside world that segregation was essential to liberty and civic order. In the

glare of unfavorable media attention and with the pressure of the Kennedy

administration and the federal courts bearing down on Alabama, die-hard

segregationists had seen the balance of political and legal power shift in the

Freedom Riders’ favor. Even though many white Alabamians seethed with

resentment against outside agitators in the aftermath of the Freedom Rides,

the crisis had not led to white solidarity on matters of politics and racial

control. On the contrary, the use of violence to maintain segregation had

convinced some Alabama segregationists that the irresponsibility of politi-

cians such as Connor was actually jeopardizing the future of segregation.

492 Freedom Riders

And in a few cases, notably among image-conscious businessmen, opposition

to extremism had led to doubts about the viability of segregation itself. In a

sense, the outbreak of violence early in the crisis had put Alabama on the

spot, effectively inoculating the state from further official complicity with

violence. By early 1962 the battle of the Freedom Rides was essentially over,

and even Connor realized that there was no politically acceptable alternative

to compliance with the ICC order.

Echoes of the Freedom Rider struggle continued to reverberate through-

out Alabama, however, as Connor and other hard-core white supremacists

pursued the wider war against desegregation. Frequently targeting the local

activists who had collaborated with the Freedom Riders, they mounted an

aggressive counter-attack that put the movement on the defensive in many

areas of the state. Indeed, despite the successful desegregation of transit fa-

cilities, 1962 would prove to be a year of frustration for those who had hoped

that the Freedom Riders’ victory would accelerate the pace of change in Ala-

bama. The disappointments began on New Year’s Day when Birmingham

officials circumvented a federal district court desegregation order by simply

closing all of the city’s parks; not even a petition signed by more than twelve

hundred “moderate” whites could convince the city commission to reopen

the parks on an integrated basis. On January 8 the local movement suffered a

second setback when the U.S. Supreme Court, citing a legal technicality in-

volving a filing deadline, refused to set aside the convictions of Fred Shuttles-

worth and his Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights colleague,

the Reverend J. S. Phifer, on a 1958 disorderly conduct charge. Even though

their convictions were based on an unconstitutional enforcement of a local

bus segregation statute, Shuttlesworth and Phifer served thirty-six days in

jail before pressure from a national sympathy campaign organized by SCLC

secured their release on bail.

In the meantime, Federal District Court Judge Hobart Grooms dealt

the movement another blow on January 16, when he sentenced five of the

Anniston bombers to one-year probation terms and allowed a sixth to serve

time concurrently with a sentence for burglary. The blatant inconsistency

with the treatment of Shuttlesworth and Phifer was disheartening to move-

ment leaders, who had expected long jail terms for the Anniston bombers, all

of whom had pleaded guilty. That night, things got even worse when

Klansmen dynamited three of Birmingham’s black churches. In the after-

math of the bombings, Connor cynically told reporters: “We know the Ne-

groes did it.” Even more upsetting was the FBI’s refusal to investigate the

bombings, compounded by Burke Marshall’s confession that he couldn’t force

Hoover and his agents to do so. The inability of government officials at any

level to protect movement activists from violent retribution was also evident

in Huntsville, where CORE field secretaries Hank Thomas and Richard Haley

were trying to organize a local CORE chapter. After Thomas helped a group

of Alabama A&M students launch a series of sit-ins at downtown lunch

Epilogue: Glory Bound 493

counters in early January, the police made forty-nine arrests and refused to

intervene when local white supremacists sprayed the former Freedom Rider

and a local white CORE supporter with caustic mustard oil. Despite these

and other forms of harassment, and declining support from a frightened lo-

cal black community, Thomas and Haley hung on for a nearly a month. But

they were forced to withdraw in early February, when a state court issued a

sweeping injunction prohibiting CORE from conducting operations anywhere

in Alabama.

Although it proved to be temporary, CORE’s expulsion from Alabama

was alarming. When Martin Luther King visited Birmingham on February

12 to address a mass meeting honoring Shuttlesworth and Phifer, he could

not conceal his concern for the future of the movement in the state. “I wish I

could tell you our road ahead is easy,” he told the crowd at the Sixteenth

Street Baptist Church, the future site of a senseless 1963 bombing that took

four innocent lives. “That we are in the promised land, that we won’t have to

suffer and sacrifice anymore, but it is not so. We have got to be prepared.

The time is coming when the police won’t protect us, the mayor and com-

missioner won’t think with clear minds. Then we can expect the worst.” As

any of the Alabama Freedom Riders could have attested, King’s concern was

well-founded; indeed, the physical vulnerability of movement activists or

anyone associated with them had been confirmed in a Montgomery court-

room earlier in the day when Claude Henley, after being convicted of as-

saulting two NBC cameramen during the Montgomery riot, escaped with a

fine of only one hundred dollars.

17

None of these concerns or disappointments seemed to faze Shuttlesworth,

however. When he emerged from jail on March 1, he was full of bluster.

“Whites can’t stop us now,” he asserted. “Negroes are beginning to realize

Birmingham is not so powerful after all—not in the face of a federal edict.

. . . There was no peace for ‘Bull’ when I was in jail and certainly there will be

no peace for him now that we are out.” Other movement leaders were also

eager to project an image of confidence, and later in the week King and Roy

Wilkins attended an Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights ban-

quet to celebrate Shuttlesworth’s and Phifer’s release. In a show of solidarity

at a mass meeting following the banquet, Wilkins declared that “the courage

and persistence of these men and of their people reveal the shame of this

city,” and he went on to encourage local activists to attack the entire range of

segregated institutions. At the banquet itself, Shuttlesworth stole the show

when he expressed relief that Connor had survived a recent traffic accident.

“I am glad it didn’t kill him,” he told the crowd, with a smile. “I want to

pester him some more. I am glad it did not put his eye out, for I want him to

see me some more when I ride the buses with Negro drivers later on.” To

make his point, Shuttlesworth promptly offered his help to a group of mili-

tant Miles College activists planning a boycott of Birmingham’s segregated

494 Freedom Riders

department stores. By mid-March the boycott was in full swing, with leaflets

urging black citizens to “Wear Your Old Clothes for Freedom.”

Shuttlesworth’s involvement in the boycott led to yet another arrest and

conviction in early April, but less than two weeks later he and his Alabama

Christian Movement for Human Rights colleagues reaffirmed their deter-

mination to withstand intimidation by hosting a major civil rights confer-

ence co-sponsored by the Southern Conference Education Fund, SCLC, and

SNCC. Advertised as a series of workshops designed to explore “Ways and

Means to Integrate the South,” the racially integrated gathering attracted

some of the movement’s most prominent activists, including Ella Baker, Kelly

Miller Smith, Anne Braden, and the former Freedom Riders C. T. Vivian

and Jim Forman. During the two days of meetings, Connor dispatched a

pack of police photographers to record the presence of known subversives,

but he made no attempt to disrupt the proceedings.

To Shuttlesworth, Connor’s restraint was added confirmation of white

supremacists’ propensity to back off in the face of resolute action. As he had

told a mass meeting in late March: “When the white people see you mean

business, they will step aside.” Others, however, were convinced that only

the politics of the moment had kept the conference delegates out of jail and

prevented Shuttlesworth’s provocative strategy from backfiring. At the time,

Connor was a struggling gubernatorial candidate trying to broaden his nar-

row political base. Having already created a furor by curtailing the local dis-

tribution of surplus food to poor blacks, as an indirect retaliation against the

downtown boycott, he could ill afford another incident that reinforced his

image as an extremist. Once he was eliminated from the field of Democratic

candidates in the May 8 primary, he faced fewer constraints, but by then the

provocation of the integrated conference had passed.

18

Connor’s poor showing in the primary—he received fewer than twenty-

five thousand votes statewide and finished a distant fifth behind the front-

runner, Judge George C. Wallace, moderate Tuscaloosa lawyer Ryan

deGraffenreid, the liberal-leaning two-time former governor Jim Folsom,

and Attorney General MacDonald Gallion—was a clear indication that even

a muted form of his violence-tinged politics did not play well outside of Klan

circles and a few Birmingham neighborhoods. But, to the dismay of move-

ment activists, Connor’s defeat did not bring a turn toward moderation. On

the contrary, with Wallace’s victory over deGraffenreid in the runoff pri-

mary, the movement faced a more sophisticated and powerful version of what

historian and biographer Dan Carter later called “the politics of rage.” Hav-

ing lost to John Patterson in the 1958 gubernatorial primary, “Alabama’s

Fighting Judge,” as Wallace liked to call himself, had vowed that “no other

son-of-a-bitch will ever out-nigger me again.” And he more than kept his

promise four years later. With Patterson ineligible to succeed himself under

Alabama law, Wallace emerged as the state’s most popular defender of sov-

ereignty, states’ rights, and segregation. Appropriating and capitalizing on

Epilogue: Glory Bound 495

Patterson’s feud with the Kennedys, he invoked the specter of invading Free-

dom Riders throughout the primary campaign.

19

Although Wallace never went quite as far as Connor, who began his

campaign in January with a pledge to purchase “one hundred new police

dogs for use in the event of more Freedom Rides,” he went far enough to

garner the Birmingham commissioner’s support in the run-off. On May 17,

the eighth anniversary of Brown, Connor endorsed Wallace as the best man

to protect Alabama from “the filthy hands of the NAACP and CORE.”

Wallace did his best to live up to this billing, stopping just short of violent

resistance and punctuating his speeches with vivid rhetorical attacks on out-

side agitators. While he ultimately focused on the school desegregation is-

sue, promising to “stand in the schoolhouse door” if necessary, much of his

rage during the spring and summer of 1962 was directed at the Freedom

Riders and their meddling federal accomplices, especially Judge Frank

Johnson, whom he labeled “a low-down, carpet-baggin’, scalawagin’, race-

mixin’ liar.” He also singled out SNCC as a menace to the state, particularly

after field secretary and former Freedom Rider Bob Zellner became involved

in a series of sit-ins and mass marches conducted by Talladega College stu-

dents, some of whom had traveled to nearby Anniston the previous spring to

protest the burning of the CORE freedom bus. Following a cross-burning

on campus, dozens of arrests, and several confrontations between students

and police in April, Attorney General Gallion obtained a temporary injunc-

tion from a state judge prohibiting further demonstrations. But Zellner’s

continued presence in Alabama provided Wallace and others with a conve-

nient scapegoat in an atmosphere of escalating tension.

20

In Talladega and many other communities, there was an unmistakable

air of intimidation and impending violence, and Zellner was just one of many

activists who were either threatened or assaulted by Alabama vigilantes in

1962. Prior to a planned attempt to desegregate the Birmingham airport

restaurant in July, the FBI informed Shuttlesworth that they had uncovered

a conspiracy to assassinate him during the sit-in. Two months later SCLC’s

annual conference, meeting for the first time in Birmingham, was disrupted

by Roy James, a twenty-four-year-old neo-Nazi from Alexandria, Virginia,

who rushed onto the stage and struck Martin Luther King in the face. Prior

to the attack, the convention had gone smoothly and preconvention negotia-

tions between Shuttlesworth and a committee of white businessmen had

yielded an informal agreement to remove Jim Crow signs from downtown

businesses in exchange for a promise to suspend the six-month-old boycott.

But the assault reminded the SCLC delegates that Birmingham remained a

violent and inhospitable place for movement activists—a reality confirmed

in early October when Connor ordered the signs to be reinstalled and even

more dramatically in December when Klansmen bombed Bethel Baptist

Church for the third time.